Abstract

AIM

To produce a radiological grading of gastric traumatic injuries.

METHODS

In our study, we retrospectively analyzed 32 cases of blunt gastric traumatic injuries and compared computed tomography (CT) data with patients’ surgical or medical development. In all cases, a basal phase was acquired, and an intravenous contrast material was administered via an antecubital venous catheter with acquisition in the venous phase (70-90 s). In addition, a further set of delayed scans was performed 4-5 min after the first scanning session, without supplementary intravenous contrast material, to identify or better define areas of active bleeding. All CT examinations were retrospectively reviewed by two radiologists, with more than 5 years of experience in emergency radiology, to detect signs of gastric injuries and/or associated abdominal lesions according to literature data. Specific CT findings for gastric rupture include luminal content extravasation and discontinuity of the gastric wall, while CT findings suggestive of injury consisted of free peritoneal fluid, extraluminal air, pneumatosis, and thickening and hematoma of gastric wall.

RESULTS

We found 32 gastric traumatic injuries. In 22 patients (68.8%), the diagnosis was based on the surgical findings; in the other 10 patients (31.2%), the diagnosis was based on the clinical and CT radiological data. We observed discontinuity of the gastric wall and luminal content extravasation in 1 patient (3.1%); in 10 patients (31.2%), there was extra-luminal air in the peritoneum. In 28 patients (87.5%), there was peritoneal fluid, which was blood in 14 patients (hematoma in 11 patients and contrast material extravasation from active bleeding in 3 patients). In 15 patients (46.9%), there was gastric wall thickening. In 3 patients, it was possible to identify a prevalent involvement of the external layer of the gastric wall, whereas, in 2 patients, the inner side of the gastric wall presented with major involvement. In 3 patients (9.4%), pneumatosis of the gastric wall was detected. In 19 (59.4%) patients, the stomach was full. The fundus was the most frequently damaged part of the stomach because it was involved in 17 patients (53.1%). Based on the observed data, we identified four grades of gastric lesions.

CONCLUSION

A radiologic score is helpful for guiding the diagnosis and management (surgical or conservative) of gastric blunt traumatic injuries and stratify patients according to short-term outcomes.

Keywords: Gastric injuries, Blunt trauma, Computed tomography grading, Emergency radiology, Stomach rupture

Core tip: Although a wide spectrum of computed tomography findings has been described for gastric blunt traumas, no systematic instrumental approach exists in this setting. In this study the authors produced a radiological grading of gastric traumatic injuries that might play a role in both the diagnostic phase of the emergency setting and prognostic stratification of these patients.

INTRODUCTION

In Europe, blunt trauma is the main cause of death in the first four decades of life, and there is a substantial rate of permanent disability[1,2].

Blunt trauma involving the stomach is infrequent with a reported incidence of 0.4%-1.7%[3-5]; however, such trauma may cause extremely high individual and social consequences[6].

Management of traumatic injuries requires a high index of suspicion, rapid investigation, accurate classification and well-defined treatment protocols to ensure optimal outcomes and reduce long-term disabilities[7].

Clinical signs and symptoms of gastrointestinal injuries often require hours before they appear, and a delayed diagnosis may prolong the period of peritoneal contamination, increasing the incidence of intra-abdominal complications, such as abscess, sepsis, and mortality[8,9]. Moreover, the differentiating between injuries requiring surgery and those that can be treated conservatively may be very challenging[10].

The widespread introduction of traumatic injury classifications, based on clinical and instrumental findings for most of the abdominal organs, has greatly improved the management of patients with traumatic injuries[7]. Although a wide spectrum of computed tomography (CT) findings has been described for gastric blunt traumas, no systematic instrumental approach exists in this setting[11]. For this reason, we sought to produce a radiological grading of gastric traumatic injuries in our study that might play a role in both the diagnostic phase of the emergency setting and prognostic stratification of these patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Over a 14-year period, from January 2002 to December 2015, a total of 32 patients (22 males and 10 females; age range 16-82 years, mean age: 41.34) with evidence of blunt gastric traumatic injuries were retrospectively identified based on the final surgical and radiological reports.

The diagnosis of gastric injury was based on the surgical findings in 22 patients, whereas the diagnosis for 10 patients was based on the clinical and radiological findings. CT scan was performed in all patients.

CT scans were performed with different scanners over time, reflecting the evolution of the technique, ranging from single slice helical CT to 64-row detector CT. In all cases, a basal phase was acquired, and an intravenous contrast material was administered via an antecubital venous catheter with acquisition in the venous phase (70-90 s). In addition, a further set of delayed scans was performed 4-5 min after the first scanning session, without supplementary intravenous contrast material, to identify or better define areas of active bleeding.

All CT examinations were retrospectively reviewed by two radiologists, with more than 5 years of experience in emergency radiology, to detect signs of gastric injuries and/or associated abdominal lesions according to literature data. Specific CT findings for gastric rupture include luminal content extravasation and discontinuity of the gastric wall, while CT findings suggestive of injury consisted of free peritoneal fluid, extraluminal air, pneumatosis, and thickening and hematoma of gastric wall[11].

We evaluated the relevance of each instrumental pattern of gastric blunt injury, comparing the radiological signs with surgical findings or clinical follow-up, to propose a radiologic classification for this type of injury.

RESULTS

We found 32 gastric traumatic injuries. In 22 patients (68.8%), the diagnosis was based on the surgical findings; in the other 10 patients (31.2%), the diagnosis was based on the clinical and CT radiological data.

We observed (Table 1) discontinuity of the gastric wall and luminal content extravasation in 1 patient (3.1%); in 10 patients (31.2%), there was extra-luminal air in the peritoneum (it was linked to pneumoretroperitoneum in 2 patients and to pneumomediastinum in 1 patient). In 28 patients (87.5%), there was peritoneal fluid, which was blood in 14 patients (hematoma in 11 patients and contrast material extravasation from active bleeding in 3 patients). In 15 patients (46.9%), there was gastric wall thickening. In 3 patients, it was possible to identify a prevalent involvement of the external layer of the gastric wall, whereas, in 2 patients, the inner side of the gastric wall presented with major involvement. In 3 patients (9.4%), pneumatosis of the gastric wall was detected. In 19 (59.4%) patients, the stomach was full.

Table 1.

Computed tomography signs of gastric blunt traumatic injuries

| CT signs of gastric blunt traumatic injuries (n. 57 in 32) | |

| Gastric wall discontinuity | 1 |

| Extraluminal air | 10 |

| Peritoneal fluid | 28 |

| Hematoma | 11 |

| Contrast material | 3 |

| Luminal content extravasation | 1 |

| Gastric wall thickening | 15 |

| Pneumatosis of gastric wall | 3 |

CT: Computed tomography.

Twenty-seven patients (84.4%) presented with associated abdominal lesions. The spleen was the most frequently involved organ (43.8%), which was followed by the liver (28.1%), kidneys (12.5%), large bowel (6.3%), mesentery (9.4%) and pancreas (3.1%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Abdominal associated lesions

| Abdominal associated lesions (n. 33 in 27 patients) | |

| Large bowel | 2 |

| Spleen | 14 |

| Liver | 9 |

| Left kidney | 3 |

| Right kidney | 1 |

| Pancreas | 1 |

| Mesentery | 3 |

The fundus was the most frequently damaged part of the stomach because it was involved in 17 patients (53.1%) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Location of gastric lesions

| Location of gastric lesions | |

| Fundus | 17 |

| Body | 15 |

| Anterior wall | 7 |

| Greater curvature | 2 |

| Small curvature | 1 |

| Posterior surface | 3 |

| Antrum | 3 |

| Not detectable | 1 |

All patients with extraluminal air and/or peritoneal hematic collections underwent surgery. Among the 22 patients with a surgical diagnosis of gastric lesions, 14 showed radiological signs that were directly related to gastric involvement (thickening of the gastric wall, extraluminal air in proximity to the gastric wall and discontinuity of the gastric wall) (66.6%). In the other 8 patients, a gastric lesion was diagnosed during surgery, but it was not detected on the CT scan.

Peritoneal fluid was detected in all patients who underwent surgery, but it was also present in 6 of 10 patients who were conservatively treated (60%).

Nine out of 10 patients who had not undergone surgery showed a thickened gastric wall on CT. Perigastric pneumatosis was the only sign in one patient.

Pneumatosis of the gastric wall was observed in 3 patients (9.4%), two with significant gastric lesion requiring surgery and one who recovered spontaneously.

Based on the observed data, we identified four grades of gastric lesions.

Cases with minor contusion with parietal thickening alone (Figure 1), which did not involve the fundus and was not associated with the peritoneal fluid, and only included portal pneumatosis (Figure 2) detected by CT scan, do not require surgical intervention (grade 1 lesion). Cases of minor lacerations with high attenuating focal thickening involving the mucosal side and with a small level without hematic peritoneal fluid (Figure 3) require monitoring (grade 2 lesion). Cases with partial laceration with parietal hematoma and/or stretching of the external layer and peritoneal hematic collection (Figure 4) require careful monitoring (grade 3 lesion). Cases with full thickness rupture, necrosis, food in peritoneal cavity, vascular involvement and contrast media extravasation (Figure 5) require intervention (grade 4 lesion) (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Wall thickening of the gastric body (arrow). Surgery was not required. Grade 1 lesion.

Figure 2.

Isolated gastric pneumatosis after abdominal trauma (arrows). Spontaneous recovery. Grade 1 lesion.

Figure 3.

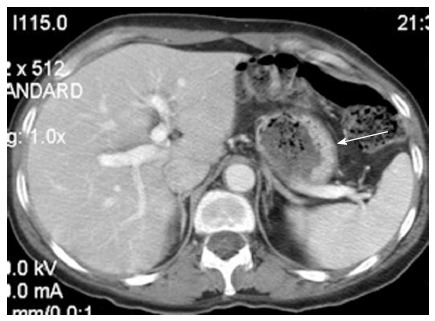

Blood in the gastric lumen (arrow). Follow-up without surgery. Grade 2 lesion.

Figure 4.

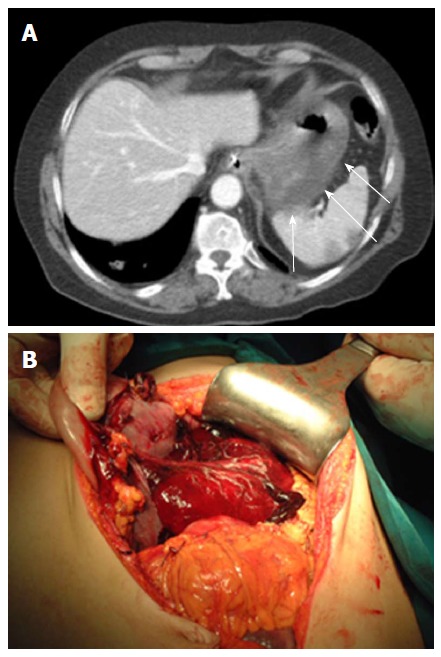

Parietal hematoma. A: Parietal hematoma: Thickening with high-attenuation in the external layer of gastric wall (arrows). Grade 3 lesion. Follow-up with subsequent surgery for worsening symptoms and peritoneal reaction; B: External layer gastric wall hematoma confirmed at surgery.

Figure 5.

Gastric rupture. A: Gastric wall rupture (white arrow): Peritoneal fluid (white arrowhead) with homogeneous hyperdense components from blood (black arrow), pneumoperitoneum with a bubble of gas located close to the gastric lesion (black arrowheads). Grade 4 lesion; B: Gastric rupture confirmed at surgery.

Table 4.

Grading computed tomography of gastric blunt traumatic injuries

| Pathology | CT signs | Treatment | |

| Grade 1 | Gastric contusion | Gastric wall thickening No peritoneal fluid Perigastric pneumatosis | No surgery |

| Grade 2 | Minor lacerations involving the mucosal side | High-attenuation hematoma confined to the inner side, blood in the gastric lumen Small amount of non-bloody peritoneal fluid | Follow-up |

| Grade 3 | Partial laceration with parietal hematoma and/or stretching of the external layer | Peritoneal hematoma collection, gastric wall thickening with high-attenuation of the external side | Close follow-up/ surgery |

| Grade 4 | Full thickness rupture Vascular involvement (necrosis or active bleeding) | Extraluminal air Luminal content extravasation Contrast material extravasation | Emergency surgery |

CT: Computed tomography.

DISCUSSION

Trauma currently represents a major social and sanitary problem with characteristics of an epidemic illness involving especially young people and with a high residual morbidity.

Gastric blunt traumas often occur after high velocity impact involving the epigastric region when the stomach is full, in the post-prandial phase[12-14], due to the positive correlation between the wall pressure and cavity radius, as explained in Laplace’s law. These data were confirmed by an experimental model of rats that also demonstrated a higher frequency and grade of injury of other parenchymal organs in rats with full stomachs[15]. Moreover, a full thickness rupture is more frequently observed at the level of the fundus[11,16]. The mechanisms responsible for gastric injuries in blunt trauma include tangential tearing along fixed points, increased intraluminal pressure, and crushing against vertebral bodies[17].

In the management of trauma patients, diagnostic imaging plays a key role, especially CT, which is considered the gold standard for accurate and fast detection of abdominal injuries.

To standardize and improve clinical outcomes, especially for prompt identification of patients who need to be referred to surgery, radiological scores have been widely used.

Although they represent 0.4%-1.7% of all abdominal traumas[12,18-20], gastric blunt traumatic injuries have rarely been described in the medical literature[12,18-21], and a CT grading classification is not yet available. For this reason, we propose a radiological score based on our experience and literature data to better classify these lesions (Table 4).

Full thickness rupture of the stomach requires prompt surgical intervention, which is also the cases with vascular involvement, infarct or hemorrhage. However, in several cases, a parietal thickening may be observed on CT scans, bringing attention to the stomach without necessarily requiring surgery.

In some cases, the gas content of the stomach, which usually plays a protective role, can dissect the mucosal layer and pass into the gastric veins, causing perigastric pneumatosis and, subsequently, portal pneumatosis[10,11,22], a condition that could be related to more serious conditions, such as an intestinal infarction from traumatic shock.

Extraluminal air, hematic peritoneal collection and active bleeding suggest patients should be referred to surgery. Proximal lesions with fundus involvement more often require surgery. In other cases, less aggressive treatment and surveillance may be indicated.

However, in 33.3% of our patients who required surgery, a gastric injury was detected on surgical intervention without any previous radiological suspicion. The use of a simple classification could help guide medical practice.

In conclusion, traumatic injuries require a careful and systematic treatment approach because of their economic and social relevance. For these reasons, uncommon lesions require attention, and a meta-analysis should be performed.

COMMENTS

Background

Gastric injuries after blunt trauma have rarely been reported in the literature; however, preoperative recognition and staging of these lesions play a critical role in patient management.

Research frontiers

The widespread introduction of traumatic injury classifications, based on clinical and instrumental findings for most of the abdominal organs, has greatly improved the management of patients with traumatic injuries. Although a wide spectrum of computed tomography findings has been described for gastric blunt traumas, no systematic instrumental approach exists in this setting.

Innovations and breakthroughs

The authors produced a radiological grading of gastric traumatic injuries.

Applications

The study results suggest that a radiological grading of gastric traumatic injuries might play a role in both the diagnostic phase of the emergency setting and prognostic stratification of these patients.

Peer-review

The authors investigated gastric blunt traumatic injuries about computed tomography classification. The work is good and well designed.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: Approved by ethical committee of SUN-Monaldi n.940 August 2, 2016.

Informed consent statement: Participants informed consent was not obtained to be enrolled in this study, but data are anonymized and risk of identification is low.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors have no conflict of interests.

Data sharing statement: No addition data are available.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Peer-review started: July 16, 2016

First decision: September 2, 2016

Article in press: December 2, 2016

P- Reviewer: Bazeed MF, Gao BL, Shen J S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Bode PJ, Edwards MJ, Kruit MC, van Vugt AB. Sonography in a clinical algorithm for early evaluation of 1671 patients with blunt abdominal trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:905–911. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.4.10587119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Beeck EF, van Roijen L, Mackenbach JP. Medical costs and economic production losses due to injuries in the Netherlands. J Trauma. 1997;42:1116–1123. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199706000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Takabe K, Ohtani T, Muto I, Takano Y, Miyauchi T, Kato H, Sekido H, Ohki S, Hatakeyama K, Shimada H. Computed tomography (CT) findings of gastric rupture after blunt trauma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2000;47:901–903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oncel D, Malinoski D, Brown C, Demetriades D, Salim A. Blunt gastric injuries. Am Surg. 2007;73:880–883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruscagin V, Coimbra R, Rasslan S, Abrantes WL, Souza HP, Neto G, Dalcin RR, Drumond DA, Ribas JR. Blunt gastric injury. A multicentre experience. Injury. 2001;32:761–764. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(01)00081-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoyt DB, Coimbra R, Potenza BM. Trauma System, Triage, and Transport. In: Feliciano DV, Mattox KL, Moore EE, Bonnie RJ, Fulco CE, et al., editors. Magnitude and Costs. Reducing the burden of injury. Advancing Prevention and Treatment. Washington, DC, United States: National Academy Press; 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oniscu GC, Parks RW, Garden OJ. Classification of liver and pancreatic trauma. HPB (Oxford) 2006;8:4–9. doi: 10.1080/13651820500465881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brody JM, Leighton DB, Murphy BL, Abbott GF, Vaccaro JP, Jagminas L, Cioffi WG. CT of blunt trauma bowel and mesenteric injury: typical findings and pitfalls in diagnosis. Radiographics. 2000;20:1525–1536; discussion 1536-1537. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.6.g00nv021525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butela ST, Federle MP, Chang PJ, Thaete FL, Peterson MS, Dorvault CJ, Hari AK, Soni S, Branstetter BF, Paisley KJ, et al. Performance of CT in detection of bowel injury. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:129–135. doi: 10.2214/ajr.176.1.1760129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scaglione M, de Lutio di Castelguidone E, Scialpi M, Merola S, Diettrich AI, Lombardo P, Romano L, Grassi R. Blunt trauma to the gastrointestinal tract and mesentery: is there a role for helical CT in the decision-making process? Eur J Radiol. 2004;50:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lassandro F, Romano S, Rossi G, Muto R, Cappabianca S, Grassi R. Gastric traumatic injuries: CT findings. Eur J Radiol. 2006;59:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Courcy PA, Soderstrom C, Brotman S. Gastric rupture from blunt trauma. A plea for minimal diagnostics and early surgery. Am Surg. 1984;50:424–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siemens RA, Fulton RL. Gastric rupture as a result of blunt trauma. Am Surg. 1977;43:229–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takabe K, Hatakeyama K. Computed tomography is useful for preoperative workup of gastric rupture caused by blunt trauma. Surg Today. 2009;39:1109. doi: 10.1007/s00595-009-4069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kafadar H, Kafadar S, Tokdemir M. Comparison of internal organ injuries by blunt abdominal trauma in rats with empty or full stomach. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2014;20:395–400. doi: 10.5505/tjtes.2014.92331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shinkawa H, Yasuhara H, Naka S, Morikane K, Furuya Y, Niwa H, Kikuchi T. Characteristic features of abdominal organ injuries associated with gastric rupture in blunt abdominal trauma. Am J Surg. 2004;187:394–397. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madiba TE, Hlophe M. Gastric trauma: a straightforward injury, but no room for complacency. S Afr J Surg. 2008;46:10–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brunsting LA, Morton JH. Gastric rupture from blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1987;27:887–891. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pikoulis E, Delis S, Tsatsoulis P, Leppäniemi A, Derlopas K, Koukoulides G, Mantonakis S. Blunt injuries of the stomach. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:937–939. doi: 10.1080/110241599750008035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Semel L, Frittelli G. Gastric rupture from blunt abdominal trauma. N Y State J Med. 1981;81:938–939. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nanji SA, Mock C. Gastric rupture resulting from blunt abdominal trauma and requiring gastric resection. J Trauma. 1999;47:410–412. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199908000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kingsley DD, Albrecht RM, Vogt DM. Gastric pneumatosis and hepatoportal venous gas in blunt trauma: clinical significance in a case report. J Trauma. 2000;49:951–953. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200011000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]