Abstract

Species of Tranzscheliella have been reported as pathogens of more than 30 genera of grasses (Poaceae). In this study, a combined morphological and molecular phylogenetic approach was used to examine 33 specimens provisionally identified as belonging to the T. hypodytes species complex. The phylogenetic analysis resolved several well-supported clades that corresponded to known and novel species of Tranzscheliella. Four new species are described and illustrated. In addition, a new combination in Tranzscheliella is proposed for Sorosporium reverdattoanum. Cophylogenetic analyses assessed by distance-based and event-cost based methods, indicated host switches are likely the prominent force driving speciation in Tranzscheliella.

The genus Tranzscheliella (Ustilaginales) contains 17 species, which systematically infect the culms and inflorescences of about 33 genera of grasses (Poaceae) widely distributed around the world1,2. Lavrov3 first proposed the genus Tranzscheliella (type T. otophora on Stipa pennata, Turkmenistan) based on the presence of spores with two small bipolar cells, which were considered by Vánky4 to be circular broken parts of the thick exospore. Vánky1,4,5 broadened the concept of Tranzscheliella to include species with superficial, blackish brown sori that are either naked or have an ephemeral peridium on the culms or floral axis of grasses, and possess small (<8 μm diam.) spores. Molecular studies have shown that Tranzscheliella is monophyletic6,7.

With 165 grass species as hosts, T. hypodytes s. lat.8, represents a species complex that needs revision by modern molecular assessments1. Fischer and Hirschhorn9 noted more than 70 years ago that T. hypodytes (as Ustilago hypodytes) had for many years been applied to a complex of fungi, rather than a single species. The nomenclature and taxonomy of T. hypodytes has remained confused, with numerous synonyms as well as misidentified hosts reported in the scientific literature1.

Smut fungi are often host specific and host range is an important criterion for recognition of genera and species6,10, often supporting phylogenetic and biological studies11,12,13,14. Cospeciation was traditionally the main explanation for host-parasite cophylogenies15,16. With more available data and improved tools for cophylogenetic analyses, host switches rather than cospeciation, has become currently the most likely explanation for the diversification of many parasites, including fungal pathogens17,18. Host-shift speciation rather than cospeciation explained the cophylogenetic patterns of the smut fungus genus Anthracoidea found on species of the genus Carex (Cyperaceae)19.

Molecular phylogenetic methods have rarely been applied to Tranzscheliella spp. Further the cophylogenetic relationships between these smut fungi and their hosts are unknown. The aim of this study was to identify specimens that had been provisionally identified as Tranzscheliella hypodytes, mostly from China, using a combined morphological and molecular phylogenetic approach. This study resulted in the recognition of host specific species of Tranzscheliella, some of which are described here as new. Cophylogenetic analyses were used to determine the most likely explanation for speciation in Tranzscheliella.

Results

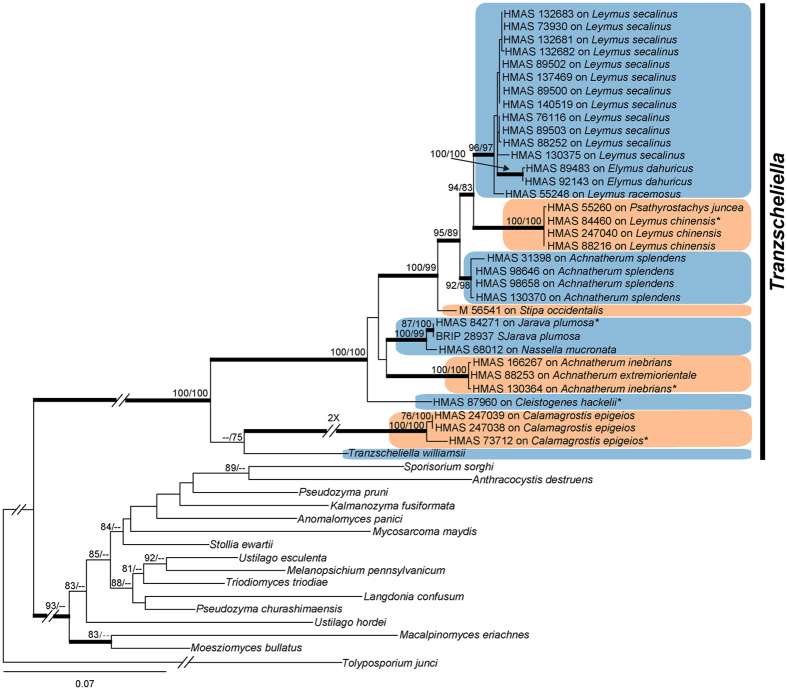

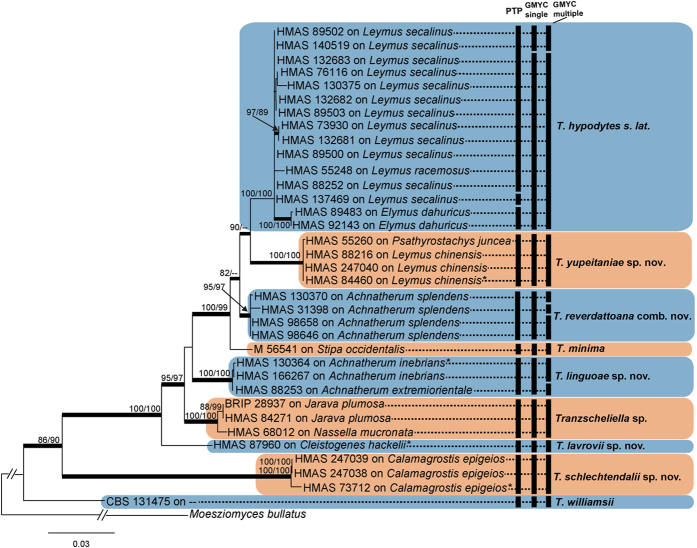

The GenBank accession numbers of new sequences derived from this study, along with reference sequences, are showed in the Table 1. The sequences of the combined internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the rRNA gene and the large subunit (LSU) rRNA gene were aligned separately with gaps treated as missing characters. The evolutionary relationships of these sequences were analysed by maximum likelihood (ML) analyses and Bayesian probabilities. The inferred phylogenetic trees were consistent with each other, and only the PhyML tree is shown (Figs 1 and 2). Tranzscheliella spp. formed a well-supported monophyletic clade in the Ustilaginaceae (Fig. 1). Thirty-three specimens provisionally identified as belonging to the T. hypodytes species clustered in the seven well-supported clades (Fig. 2).

Table 1. List of species, herbarium accession numbers, hosts and GenBank accession numbers for specimens examined in this study.

| Species | Herbarium no.a | Country | Host | GenBank accession no. |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | ||||

| Anomalomyces panici | BRIP 46421 | Australia | Panicum trachyrachis | DQ459348 | DQ459347 |

| Anthracocystis destruens | Ust. Exs. 472 | Romania | Panicum miliaceu | AY344976 | AY747077 |

| Dirkmeia churashimaensis | OK 96 | Japan | — | AB548947 | AB548955 |

| Kalmanozyma fusiformata | JCM 3931 | Japan | — | AB089366 | AB089367 |

| Langdonia confusum | BRIP 42670 | Australia | Aristida queenslandica | HQ013095 | HQ013132 |

| Macalpinomyces eriachnes | BRIP 39636 | Australia | Eriachne obtusa | KX686925 | KX686955 |

| Melanopsichium pennsylvanicum | H.U.V. 17548 | India | Polygonum glabrum | AY740040 | AY740093 |

| Moesziomyces bullatus | CBS 425.34 | USA | Paspalum distichum | DQ831013 | DQ831011 |

| Mycosarcoma maydis | PBM 2469 | USA | Zea mays | AY854090 | AF453938 |

| Pseudozyma pruni | BCRC 34227 | Taiwan | Prunus mume | EU379942 | EU379943 |

| Sporisorium sorghi | MP 2036 | Nicaragua | Sorgum bicolor | AY740021 | AF009872 |

| Stollia ewartii | BRIP 51818 | Australia | Sarga timorense | HQ013087 | HQ013127 |

| Tolyposporium junci | H.U.V. 17169 | Poland | Juncus bufonius | AY344994 | AF009876 |

| Tranzscheliella hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 92143 | China | Elymus dahuricus | KX832829 | KX832862 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 132682 | China | Leymus secalinus | KX832833 | KX832866 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 89502 | China | Leymus secalinus | KX832832 | KX832865 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 137469 | China | Leymus secalinus | KX832836 | KX832869 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 89500 | China | Leymus secalinus | KX832828 | KX832861 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 140519 | China | Leymus secalinus | KX832830 | KX832863 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 130375 | China | Leymus secalinus | KX832838 | KX832871 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 89503 | China | Leymus secalinus | KX832835 | KX832868 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 76116 | China | Leymus secalinus | KX832827 | KX832860 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 88252 | China | Leymus secalinus | KX832831 | KX832864 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 73930 | China | Leymus secalinus | KX832826 | KX832859 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 132681 | China | Leymus secalinus | KX832837 | KX832870 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 132683 | China | Leymus racemosus | KX832834 | KX832867 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | HMAS 89483 | China | Elymus dahuricus | KX832814 | KX832847 |

| T. lavrovii | HMAS 87960T | China | Cleistogenes hackelii | KX832843 | KX832876 |

| T. linguoae | HMAS 166276 | China | Achnatherum extremiorientale | KX832820 | KX832853 |

| T. linguoae | HMAS 88253 | China | Achnatherum inebrians | KX832818 | KX832851 |

| T. linguoae | HMAS 130364T | China | Achnatherum inebrians | KX832819 | KX832852 |

| T. minima | M 56541 | USA | Stipa occidentalis | DQ191251 | DQ191257 |

| T. reverdattoana | HMAS 55248 | China | Achnatherum splendens | KX832825 | KX832858 |

| T. reverdattoana | HMAS 98658 | China | Achnatherum splendens | KX832823 | KX832856 |

| T. reverdattoana | HMAS 98646 | China | Achnatherum splendens | KX832822 | KX832855 |

| T. reverdattoana | HMAS 31398 | China | Achnatherum splendens | KX832821 | KX832854 |

| T. schlechtendalii | HMAS 247039 | China | Calamagrostis epigeios | KX832844 | KX832877 |

| T. schlechtendalii | HMAS 247038 | China | Calamagrostis epigeios | KX832845 | KX832878 |

| T. schlechtendalii | HMAS 73712T | China | Calamagrostis epigeios | KX832846 | KX832879 |

| T. williamsii | CBS 131475 | USA | — | JN367310 | JN367338 |

| T. yupeitaniae | HMAS 130370 | China | Psathyrostachys juncea | KX832824 | KX832857 |

| T. yupeitaniae | HMAS 55260 | China | Leymus chinensis | KX832839 | KX832872 |

| T. yupeitaniae | HMAS 88126 | China | Leymus chinesis | KX832841 | KX832874 |

| T. yupeitaniae | HMAS 247040 | China | Leymus chinensis | KX832842 | KX832875 |

| T. yupeitaniae | HMAS 84460T | China | Leymus chinensis | KX832840 | KX832873 |

| Tranzscheliella sp. | HMAS 84271 | Argentina | Jarava plumosa | KX832816 | KX832849 |

| Tranzscheliella sp. | BRIP 28937 | Argentina | Jarava plumosa | KX832815 | KX832848 |

| Tranzscheliella sp. | HMAS 68012 | Ecuador | Nassella mucronata | KX832817 | KX832850 |

| Triodiomyces triodiae | BRIP 49124 | Australia | Triodia microstachya | AY740074 | AY740126 |

| Ustilago hordei | Ust. Exs. 784 | Iran | Hordeum vulgare | AY345003 | AF453934 |

| Yenia esculenta | Ust. Exs. 590 | China | Zizania latifolia | AY345002 | AF453937 |

Sequences generated in this study are shown in bold.

aMycologicum; BCRC = Bioresource Collection and Research Center, Food Industry Research and Development Institute, Hsinchu, Taiwan; BRIP = Queensland Plant Pathology Herbarium, Dutton Park, Australia; CBS = CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre, Utrecht, Netherlands; HMAS = Herbarium Mycologicum Academiae Sinicae; H.U.V. = Herbarium Ustilaginales Vánky; MP = Herbarium Meike Piepenbring; M = Botanische Staatssammlung München, Germany; Ust. Exs. = Vánky, Ustilaginales exsiccata.

TType specimen.

Figure 1. Phylogram obtained from a ML analysis based on the ITS and LSU sequence alignment.

Values above the branches represent ML bootstrap values (>75%) from RaxML and PhyML analysis respectively. Thickened branches represent Bayesian posterior probabilities (>0.95). The scale bar indicates 0.07 expected substitutions per site. *Indicates type species.

Figure 2. Phylogram obtained from a ML analysis based on the ITS and LSU sequence alignment.

Values above the branches represent ML bootstrap values (>75%) from RaxML and PhyML analyses respectively. Thickened branches represent Bayesian posterior probabilities (>0.95). The scale bar indicates 0.03 expected substitutions per site. Asterisk indicates type species. The first column depicts species recognized by PTP model. The second and third columns depict putative species recognized by the single-threshold and multiple-threshold GMYC model, respectively.

Thirty-five haplotypes of specimens provisionally identified as belonging to the T. hypodytes species complex, one as T. minima and one as T. williamsii, were used for coalescent analyses. The single-threshold general mixed Yule coalescent (GMYC) supported ten putative species, but this species delimitation scenario was not well supported by the likelihood ratio (LR) test (single-threshold: LR = 5.670471, P = 0.0587047). The multiple-threshold GMYC model provided a better fit to the ultrametric tree than a null model of uniform coalescent branching across the entire tree (multiple-threshold: LR = 7.168903, P = 0.02775189), which supported the delimitation of the taxa into thirteen putative species. The species delimitation results from GMYC and PTP analyses are summarized in Fig. 2. There was a high congruence between the PTP and multi-loci phylogenetic analyses. Both PTP and multiple-threshold GMYC analyses recovered six clades. Two clades formed single PTP groups, but multiple-threshold analysis separated each of these clades into two to three subclades. Another clade was recovered as a single group by phylogenetic analyses, but multiple-threshold GMYC and PTP analyses split this clade into two and three subclades respectively (Fig. 2). Based on concordant results from GMYC, PTP models and phylogenetic analyses, nine strongly supported clades were resolved, which represented four new species, a new combination, T. minima, a reduced T. hypodytes s. lat., and an unidentified Tranzscheliella sp. from South America. The pairwise identity of ITS sequences derived from the type of each species is shown in Table 2.

Table 2. The pairwise identity of the ITS sequences.

| Identity of the ITS sequences | T. schlechtendalii | T. lavrovii | Tranzscheliella sp. | T. linguoae | T. yupeitaniae | T. minima | T. reverdattoana | T. hypodytes s. lat. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. williamsii | 82% | 84% | 84% | 89% | 84% | 89% | 90% | 89% |

| T. schlechtendalii | 88% | 89% | 89% | 82% | 82% | 88% | 88% | |

| T. lavrovii | 93% | 93% | 90% | 93% | 95% | 91% | ||

| Tranzscheliella sp. | 93% | 91% | 92% | 94% | 91% | |||

| T. linguoae | 92% | 94% | 96% | 94% | ||||

| T. yupeitaniae | 94% | 95% | 94% | |||||

| T. minima | 98–99% | 95% | ||||||

| T. reverdattoana | 97% |

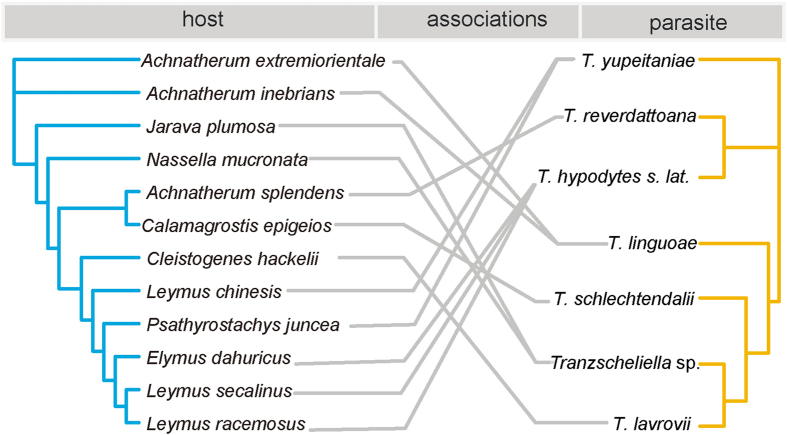

Cophylogeny analysis

The co-evolutionary relationships of the host and fungi are shown in Fig. 3. The global ParaFit test indicated that congruence between the phylogenies of Tranzscheliella species and their hosts was not significant (P = 0.50505) (Table 3). This indicated that co-speciation was not the major evolutionary force driving pathogen diversity and distribution on hosts. For the event based approach, all the reconstructions under different cost regimes were significantly better than those generated in the randomized test. Although different cost values were assigned to duplication, loss/sorting and failure to diverge, the event number inferred from analyses remained constant (0–1 duplication, 5–6 loss/sorting and 5 failure to diverge). The lowest costs were yielded by cost regime four and six, which penalized cospeciation. These two reconstructions comprised 0 cospeciation, 0 duplication, 6 host switches, 6 loss and 5 failures to diverge (Table 4).

Figure 3. The tanglegram between Tranzscheliella species and their hosts.

Fungal (right) and host grass (left) phylogenies from BI were used to generate the tanglegram using TreeMap 3.0ß.

Table 3. Results of the cophylogenetic analyses with the distance-based approach ParaFit.

| Parasite | Host | Total Links | P-value for global fit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full dataset | 12 | 12 | 0.50505 |

| T. schlechtendalii | Calamagrostis epigeios | 1 | 0.63636 |

| T. lavrovii | Cleistogenes hackelii | 1 | 0.05051 |

| Tranzscheliella sp. | Nassella mucronata | 1 | 0.38384 |

| Tranzscheliella sp. | Jarava plumosa | 1 | 0.92929 |

| T. linguoae | Achnatherum extremiorientale | 1 | 0.14141 |

| T. linguoae | Achnatherum inebrians | 1 | 0.25253 |

| T. yupeitaniae | Leymus chinesis | 1 | 0.34343 |

| T. yupeitaniae | Psathyrostachys juncea | 1 | 0.38384 |

| T. reverdattoana | Achnatherum splendens | 1 | 0.61616 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | Elymus dahuricus | 1 | 0.68687 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | Leymus secalinus | 1 | 0.63636 |

| T. hypodytes s. lat. | Leymus racemosus | 1 | 0.55556 |

Table 4. Results of the cophylogeny analyses using Jane 4.

| Cost regime | Cost assigned to each event (C, D, HS, L, FD) | Event | Total cost | RTM-P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | D | HS | L | FD | ||||

| 1 | 0, 1, 2, 1, 1 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 17 | 0.011** |

| 2 | 1, 1, 1, 1, 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 16 | 0.018** |

| 3 | 1, 0, 0, 1, 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 0.013** |

| 4 | 1, 0, 0, 1, 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 0.002** |

| 5 | 2, 0, 1, 1, 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 12 | 0.023** |

| 6 | 2, 0, 0, 1, 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 0.023** |

| 7 | 2, 0, 1, 1, 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 17 | 0.019** |

| 8 | 2, 0, 2, 1, 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 16 | 0.013** |

| 9 | 2, 0, 2, 1, 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 21 | 0.014** |

| 10 | 2, 0, 2, 2, 1 | 1–2 | 0 | 4–5 | 5 | 5 | 27 | 0.021** |

Order of event cost is: C (cospeciation); D (duplication); HS (duplication & host switch); L (loss/sorting); FD (failure to diverge). Solutions of lowest overall cost are highlighted in bolds. The P-value of each randomized test using Random Tip Mapping (RTM) method was indicated, and Asterisk (*) indicate level of significanece of RTM.

Taxonomy

Schlechtendal20 first described Caeoma hypodytes, which was subsequently transferred to several genera, namely, Ustilago, Erysibe, Uredo, Cintractia and Tranzscheliella. Hirschhorn21 considered that Ustilago hypodytes was a nomen dubium and proposed a neotype (referring to it as a lectotype) on Elymus arenarius (the type host) collected in 1884 by P. Sydow near Berlin, Germany, which had the advantage of being widely distributed in Rabenhorst’s Fungi Europea Exsiccata, Ser. 2, no. 3201. This species was subsequently transferred to T. hypodytes8. The nomenclature and taxonomy of T. hypodytes is confused, with numerous synonyms as well as misidentified hosts reported in the scientific literature1. Tranzscheliella hypodytes has long been recognized as a species complex rather than a single species9.

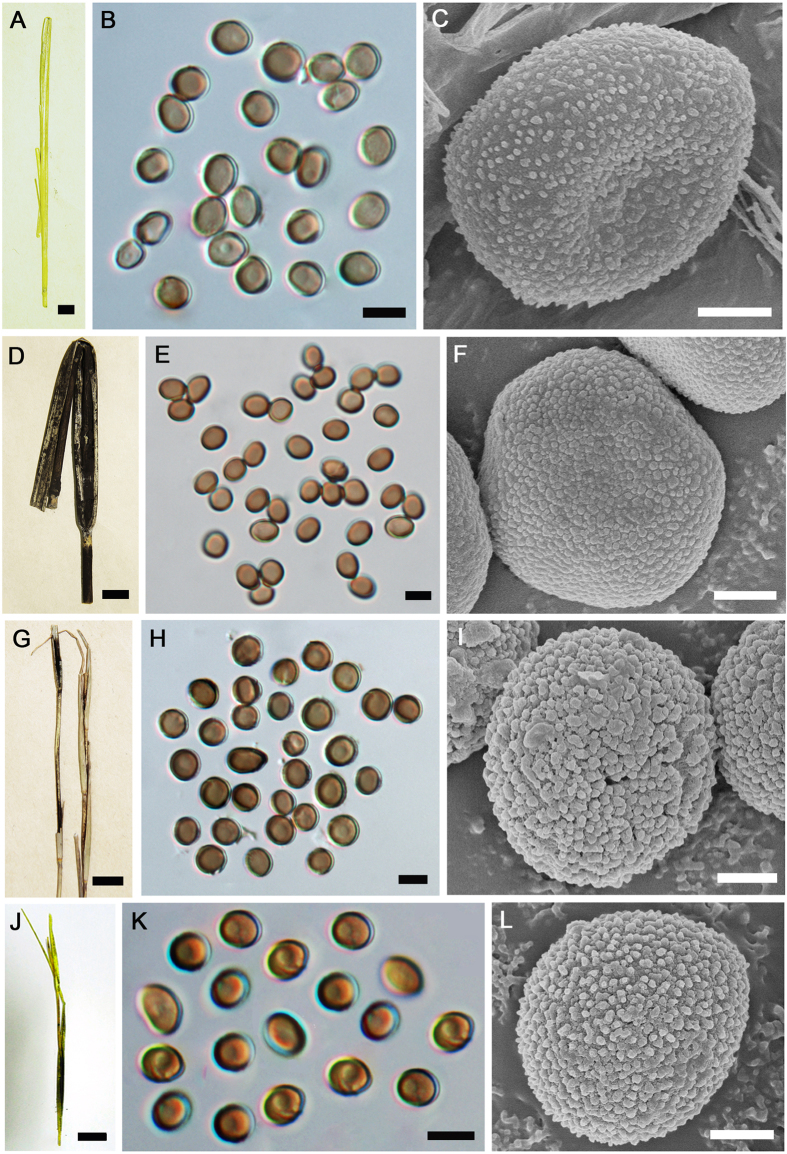

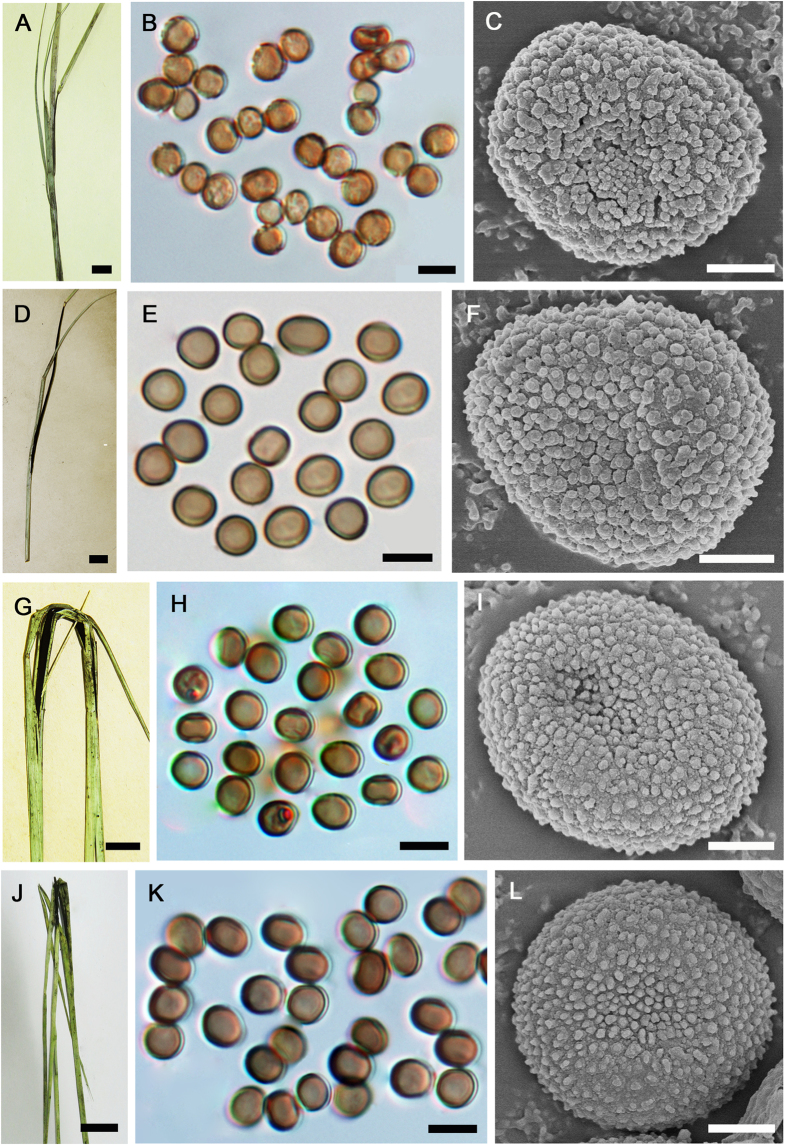

DNA could not be extracted from an isoneotype (HUV 3784) of T. hypodytes. Further, we were unable to obtain a more recent European specimen of Tranzscheliella on Elymus arenarius. Morphologically, T. hypodytes has spore walls that are smooth under light microscopy and densely, minutely, uniformly verruculose under SEM (p. 10071; Fig. 4A–C), as compared to the denser and coarser warts seen under SEM in the taxa described here.

Figure 4.

Tranzscheliella hypodytes (isoneotype HUV 3784) (A–C), Tranzscheliella schlechtendalii (HMAS 73712) (D–F), Tranzscheliella lavrovii (HMAS 87960) (G–I), and Tranzscheliella sp. (HMAS 84271) (J–L). A,D,G,J: Sori. B,E,H,K: Spores. C,F,I,L: Spores under SEM. Bars: A,D,G,J: 1 cm; B,E,H,K: 5 μm; C,F,I,L: 1 μm.

Tranzscheliella hypodytes (D.F.L. Schlechtendal) K. Vánky & E.H.C. McKenzie, Smut Fungi of New Zealand: 156, 2002, s. lat. Fig. 5J–L.

Figure 5.

Tranzscheliella linguoae (HMAS 130364) (A–C), Tranzscheliella yupeitaniae (HMAS 84460) (D–F), Tranzscheliella reverdattoana (HMAS 98658) (G–I) and Tranzscheliella hypodytes s. lat. (HMAS 89483) (J–L). A,D,G,J: Sori. B,E,H,K: Spores. C,F,I,L: Spores. C,F,I,L: Spores under SEM. Bars: A,D,G,J: 1 cm; B,E,H,K: 5 μm; C,F,I,L: 1 μm.

Sori in the culms and surrounding the upper internodes and axes of abortive inflorescences, initially covered by the leaf sheath, finally exposed, peridium absent, upper internodes and leaves reduced in size. Spore mass semi-agglutinated to powdery. Spores globose, ovoid, ellipsoidal to slightly irregular, 4.5–5.5 × (3.5−) 4–4.5 (−5) μm, light olive-brown; wall c. 0.5 μm, surface smooth, in SEM moderately, unevenly verruculose, punctuate between warts.

Specimens examined: China, Inner Mongolia, Hohhot, on Elymus dahuricus, 7 Jul. 1961, S.J. Han, Q.M. Ma & R. Liu, HMAS 92143; Xinjiang, Emin, on Leymus secalinus, 2 Jun. 1985, Z.Y. Zhao, HMAS 73930; Xinjiang, Burqin, on L. racemosus, 2 Aug. 1986, Y.W. Xi, HMAS 55248; Ningxia, Zhongwei, on L. secalinus, 28 Aug. 1997, L. Guo, HMAS 76116; Qinghai, Ledu, on L. secalinus, 27 Sep. 2003, L. Guo & H.C. Zhang, HMAS 130375; Gansu, Wuwei, on L. secalinus, 27 Sep. 2003, L. Guo & H.C. Zhang, HMAS 89503; Gansu, Wuwei, on L. secalinus, 28 Sep. 2003, L. Guo & H.C. Zhang, HMAS 88252; Gansu, Shandan, on Elymus dahuricus, 2 Otc. 2003, L. Guo & H.C. Zhang, HMAS 89483; Gansu, Yuzhong, on L. secalinus, 10 Oct. 2003, H.C. Zhang, HMAS 89502; Gansu, Lanzhou, on L. secalinus, 12 Oct. 2003, H.C. Zhang, HMAS 89500; Qinghai, Ledu, on L. secalinus, 6 Aug. 2004, L. Guo & W. Li, HMAS 132683; Gansu, Wuwei, on L. secalinus, 12 Aug. 2004, L. Guo & W. Li, HMAS 140519; Qinghai: Gonghe, on L. secalinus, 12 Aug. 2004, L. Guo & W. Li, HMAS 132681; Qinghai, Ledu, on Leymus secalinus, 12 Aug. 2004, L. Guo & W. Li, HMAS 132682; Gansu, Lanzhou, on L. secalinus, 26 Jun. 2005, L. Guo, N. Liu & Z.Y. Li, HMAS 137469.

Note — The Chinese specimens of Tranzscheliella on Elymus dahuricus and Leymus secalinus (subfamily Pooideae, tribe Triticeae) formed an unresolved polytomy in the phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 2). There is a likelihood that this clade will contain T. hypodytes s. str., as the neotype was collected on Leymus arenarius from Germany in 188421. Of note is that two specimens on Elymus dahuricus, which is native to Siberia, Mongolia and northern China, formed a strongly supported subclade that may represent a novel species. Taxonomic resolution of this polytomy needs to wait until the neotype of T. hypodytes has been sequenced and further specimens of Tranzscheliella on other triticoid grasses have been examined. Further, the spore morphology of the Chinese collections of T. hypodytes on species of Elymus and Leymus was similar to the type specimen of T. hypodytes on L. arenarius as compared with SEM images in Vánky1 (page 1007). Vánky1 listed several species of Elymus and Leymus as hosts of T. hypodytes s. lat., which is the classification that we assign to this clade.

Tranzscheliella lavroviiY.M. Li, R.G. Shivas & L. Cai, sp. nov. Fig. 4G–I.

Fungal Name: FN570369.

Etymology: Named after Russian mycologist Nikolai Nicolaevich Lavrov, who established the genus Tranzscheliella.

Sori in the culms and surrounding the upper internodes and axes of abortive inflorescences, initially covered by the leaf sheath, finally exposed, peridium absent, upper internodes and leaves reduced in size. Spore mass semi-agglutinated to powdery. Spores globose, ovoid, ellipsoidal to slightly irregular, (4.5−) 5–6.5 (−7.5) × (4.5−) 5–6 μm, light olive-brown; wall c. 0.5 μm, surface smooth, in SEM densely verruculose.

Typification: China, Inner Mongolia, Xilin Gol Meng, on Cleistogenes hackelii, 14 Jul. 2003, L. Guo, W. Li & H.C. Zhang, HMAS 87960 (holotype).

Note — Tranzscheliella lavrovii occurs on Cleistogenes hackelii (subfamily Chloridoideae, tribe Cynodonteae), which has synonyms in Diplachne and Kengia that were considered as hosts for existing names in Tranzscheliella. Vánky1 lists Diplachne spp. as a host for four species of smut fungi, T. amplexa, T. hypodytes s. lat., T. serena and U. ornata. Of these, only T. amplexa and T. hypodytes s. lat., have small spores similar in size to T. lavrovii. However T. lavrovii has more densely verruculose spores in SEM than T. amplexa. In the phylogenetic analysis, T. lavrovii was distinct from other species studied, having ITS similarity ranging from 90–95% identity (Table 2). Tranzscheliella lavrovii has slightly larger spores than the isolates of Tranzscheliella sp. on Stipa papposa (4.5–5 × 4–4.5 μm).

Tranzscheliella linguoae Y.M. Li, R.G. Shivas & L. Cai, sp. nov. Fig. 5A–C.

Fungal name: FN570370.

Etymology: Named after the Chinese mycologist Prof. Lin Guo, who specialises in the classification of Chinese smut fungi.

Sori in the culms and surrounding the upper internodes and axes of abortive inflorescences, initially covered by the leaf sheath, finally exposed, peridium absent, upper internodes and leaves reduced in size. Spore mass semi-agglutinated to powdery. Spores globose, ovoid, ellipsoidal to slightly irregular, 3.5–4 (−4.5) × 3–4 μm, light olive-brown; wall c. 0.5 μm, surface smooth, in SEM spore surface densely verruculose with irregular warts that fuse to create an irregular pattern on the spore surface.

Typification: China, Qinghai, Qilian, on Achnatherum inebrians, 2005, L. Guo & W. Li, HMAS 130364 (holotype).

Other specimens examined: China, Gansu, Tianzhu, on A. extremiorientale, 8 Oct. 2003, H.C. Zhang, HMAS 88253; Xinjiang, Urumqi, on A. inebrians, 23 Jul. 1959, Y.N. Yu, HMAS 166276.

Note —Tranzscheliella linguoae is one of four species of Tranzscheliella that infects species of Achnatherum (subfamily Pooideae, tribe Stipeae)1, which is another large polyphyletic grass genus22. The other species are T. jacksonii, T. minima and T. williamsii1. Tranzscheliella linguoae has smaller spores than T. jacksonii (8–13.5 × 8–12 μm) and T. williamsii (7–10 × 6–8 μm)1. The sori of T. linguoae lack a peridium and differ from T. minima, which has sori with a silvery to whitish fungal peridium1. In the phylogenetic analysis, specimens of T. linguoae were resolved in a well-supported monophyletic clade (Fig. 2).

Tranzscheliella reverdattoana (Lavrov) Y.M. Li, R.G. Shivas & L. Cai, comb. nov. Fig. 5G–I.

Fungal name: FN570375.

Basionym: Sorosporium reverdattoanum Lavrov, Trudy Tomsk. Gosud. Univ. 86: 86. 1934.

Sori in the culms and surrounding the upper internodes and axes of abortive inflorescences, initially covered by the leaf sheath, finally exposed, peridium absent, upper internodes and leaves reduced in size. Spore mass semi-agglutinated to powdery. Spores globose, ovoid, ellipsoidal to slightly irregular, 4–4.5 (−5) × 3.5–4 (−4.5) μm, light olive-brown; wall c. 0.5 μm, surface smooth, in SEM densely verruculose and punctuate between warts.

Specimens examined: China, Xinjiang, Baicheng, on Achnatherum splendens, 22 Jul. 1959, J.H. Yu & Y.H. Yang, HMAS 31398; Gansu, Yumen, on A. splendens, 23 Aug. 2004, L. Guo & W. Li, HMAS 98658; Gansu, Yumen, on A. splendens, 23 Aug. 2004, L. Guo & W. Li, HMAS 98646; Gansu, Yumen, on A. splendens, 23 Aug. 2004, L. Guo & W. Li, HMAS 130370. Kazakhstan, Buran, Irtysh River, on A. splendens, 7 Jul. 1928, P.N. Golovin, HUV 12100 (isotype of Sorosporium reverdattoanum).

Note — Sorosporium reverdattoanum was described from a specimen of Lasiagrostis splendens (=Achnatherum splendens) (subfamily Pooideae, tribe Stipeae) collected in Kazakhstan23. Vánky24 observed that the spores of this specimen had passed through the alimentary tracts of insects, becoming agglutinated and hence the generic placement in Sorosporium. The host, A. splendens, is especially interesting as it was shown to form a highly supported monophyletic clade that was distinct from other Old World Stipeae22. Further, Hamasha et al.22 suggested that a new genus based on A. splendens was warranted, but only after clarification of the highly polyphyletic Achnatherum.

In making this new combination, we do not accept that S. reverdattoanum is a synonym of T. minima (type on Achnatherum hymenoides, USA) as considered by Vánky1,24. Tranzscheliella reverdattoana and T. minima both have very small spores (4–6 × 3.5–5 μm for T. minima) that are densely verruculose in SEM1. However T. reverdattoana has spore surfaces with punctate warts between the verrucose warts in SEM, which are not seen in T. minima1,24. There was sequence data on GenBank for a specimen identified as T. minima (DQ191251) on Stipa occidentalis (subfamily Pooideae, tribe Stipeae) from the USA, which was found to be sister to T. reverdattoana in our phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 2). Despite not having DNA sequence data from the type specimen of S. reverdattoanum, we have chosen to transfer this species to Tranzscheliella on the basis of the (i) similar morphology between the isotype of S. reverdattoanum and the Chinese specimens, (ii) relative proximity of the collections in neighboring countries, i.e. China and Kazakhstan, (iii) unique phylogenetic placement of A. splendens and (iv) molecular diversity between the North American isolate of T. minima (represented by DQ191251) and the Chinese isolates studied here.

Tranzscheliella schlechtendalii Y.M. Li, R.G. Shivas & L. Cai, sp. nov. Fig. 4D–F.

Fungal Name: FN570371.

Etymology: Named after the great German botanist Diederich Franz Leonhard von Schlechtendal (1794–1866), who first described Caeoma hypodytes.

Sori in the culms and surrounding the upper internodes and axes of abortive inflorescences, initially covered by the leaf sheath, finally exposed, peridium absent, upper internodes and leaves reduced in size. Spore mass semi-agglutinated to powdery. Spores globose, ovoid, ellipsoidal to slightly irregular, (4.5−) 4.5–5.5 (−6) × (3.5−) 4–4.5 μm, light olive-brown; wall c. 0.5 μm, surface smooth, in SEM densely finely uniformly verruculose.

Typification: China, Inner Mongolia, Dengkou, on Calamagrostis epigeios, 4 Aug. 1996, Zhang & L. Guo, HMAS 73712 (holotype).

Other specimens examined: China, Gansu, 36° 12′ 41.7″N, 102° 02′ 63.4″, on C. epigeios, 4 Sep. 2013, Y.M. Li, R.G. Shivas, M.D.E. Shivas & Q. Chen, HMAS 247038; Gansu, 36° 12′ 41.7″N, 102° 02′ 63.4″, on C. epigeios, 4 Sep. 2013, Y.M. Li, R.G. Shivas, M.D.E. Shivas & Q. Chen, HMAS 247039.

Note — Tranzscheliella schlechtendalii is one of six species of smut fungi in the Ustilaginaceae that infect Calamagrostis (subfamily Pooideae, tribe Poeae), which is a large polyphyletic grass genus25. The other species include four Ustilago stripe smuts (U. calamagrostidis, U. corcontica, U. scrobiculata and U. striiformis)26 and T. hypodytes s. lat.1. The Ustilago stripe smuts all have larger spores that T. schlechtendalii. Vánky1 listed “? Calamagrostis epigeios” as a host of T. hypodytes s. lat., although a specimen was not found in Herbarium Ustilaginales Vánky. In the phylogenetic analysis, T. schlechtendalii was resolved on a long branch in a well-supported monophyletic clade that was sister to all other Tranzscheliella species except T. williamsii (Fig. 2).

Tranzscheliella sp. Figure 4J–L.

Sori in the culms and surrounding the upper internodes and axes of abortive inflorescences, initially covered by the leaf sheath, finally exposed, peridium absent, upper internodes and leaves reduced in size. Spore mass semi-agglutinated to powdery. Spores globose, ovoid, ellipsoidal to slightly irregular, (4−) 4.5–5 (−5.5) × (3.5−) 4–4.5 (−5) μm, light olive-brown; wall c. 0.5 μm, surface smooth, in SEM densely verruculose.

Specimens examined: Argentina, 100 km NNE Bahia Blanca, on Jarava plumosa (as Stipa papposa), 2 Dec. 1999, C. Vánky & K. Vánky, Vánky, Ust. Exs. 1110, HMAS 84271, BRIP 28937. Ecuador, on Nassella mucronata, 21 Mar. 1993, C. Vánky & K. Vánky, HUV 16016, HMAS 68012.

Note —Tranzscheliella sp. occurs on two closely related grass species, Jarava plumosa and Nassella mucronata, (subfamily Pooideae, tribe Stipeae)27 in South America. Vánky1 listed three South American species, Ustilago nummularia28, U. stipicola28 and U. spegazzinii29, as synonyms of T. hypodytes s. lat., which may represent this species. In the phylogenetic analysis, Tranzscheliella sp. was resolved in a well-supported clade (Fig. 2). Further work is needed to determine the identity of this South American species.

Tranzscheliella yupeitaniae Y.M. Li, R.G. Shivas & L. Cai, sp. nov. Fig. 5D–F.

Fungal Name: FN570377.

Etymology: Named after the Australian molecular biologist Yu Pei Tan, who collected this fungus with the authors in Inner Mongolia.

Sori in the culms and surrounding the upper internodes and axes of abortive inflorescences, initially covered by the leaf sheath, peridium absent, upper internodes and leaves reduced in size. Spore mass semi-agglutinated to powdery. Spores globose, ovoid, ellipsoidal to slightly irregular, 4–5 (−5.5) × 3–4 μm, light olive-brown; wall c. 0.5 μm, surface smooth, in SEM densely and irregularly verruculose.

Typification: China, Inner Mongolia, Barin Youqin, on Leymus chinensis, 31 Aug. 2001, L. Guo & H.C. Zhang, HMAS 84460 (holotype).

Other specimens examined: China, Xinjiang, Tacheng, on Psathyrostachys juncea, 10 Aug. 1986, Y.W. Xi, HMAS 55260; Inner Mongolia, Xilinhot, on L. chinensis, 17 Jul. 2003, L. Guo, W. Li & H.C. Zhang, HMAS 88126; Inner Mongolia, Xilinguole, on L. chinensis, 1 Jul. 2011, R.G. Shivas, M.D.E. Shivas, Y.P. Tan, Y. Zhang, L. Cai & Y.M. Li, BRIP 57343, HMAS 247040.

Note —Tranzscheliella yupeitaniae occurs on two closely related grass species, Leymus chinensis and Psathyrostachys juncea (subfamily Pooideae, tribe Triticeae)30,31. Leymus contains about 50 species found in temperate regions of China and North America, and Psathyrostachys about 10 species from Russia, Turkey and China31. Several species of Leymus were listed as hosts of T. hypodytes s. lat. by Vánky1. Tranzscheliella yupeitaniae has spores that are densely, unevenly verruculose in SEM, which differ from the densely, minutely, uniformly verruculose spores of T. hypodytes s. str.1 (p. 1007). In the phylogenetic analysis, T. yupeitaniae was resolved in a strongly supported clade (Fig. 2).

Discussion

Many of the specimens examined were herbarium specimens more than 5 years old that had not been housed in environmentally controlled conditions. The extraction and amplification of DNA from these specimens was challenging, most likely because of DNA degradation. In term of genealogical information, the ITS and LSU (linked rDNA loci) equate to a single locus. GMYC and PTP are methods primarily intended for delimiting species in single-locus molecular phylogenies32,33, and the species boundaries proposed by these methods are consistent with the phylogenetic species concept34,35. The GMYC and PTP analyses used in this study meet the basic requirements of these two methods. The GMYC method has a tendency to over-split and generate biologically unrealistic putative entities36. In this study, T. reverdattoana, T. schlechtendalii and Tranzscheliella sp., formed single PTP groups, although multiple-threshold analysis separated each of these species into two subclades (Fig. 2). These subclades were not well supported by phylogeny, morphological characters and host affiliations. Tranzscheliella schlechtendalii was sister to all other Tranzscheliella spp., with a large molecular distance (ITS sequence identity 82–89%), indicating missing data or undiscovered species.

Traditional species recognition criteria for smut fungi have been based on morphological and ecological characters, with emphasis on sori, spores, sterile cells and columellae, as well as pathogenicity on specific hosts1,13. A high degree of host specificity in most smut fungi, as postulated by earlier mycologists, has been largely confirmed by phylogenetic studies11,12,13,14,19,37,38. In this study, phylogenetic analyses of specimens of Tranzscheliella recognized eight distinct species as well as a clade that we retain as representing T. hypodytes s. lat. These seven species, T. lavrovii, T. linguoae, T. minima, T. reverdattoana, T. schlechtendalii, T. yupeitaniae and Tranzscheliella sp., appear restricted to specific grass species or closely related grass species. The unidentified Tranzscheliella sp. was found on two closely related grass species, Jarava plumosa and Nassella mucronata, from South America. Most of the remaining specimens were collected from China (Gansu, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Xinjiang and Qinghai) and neighboring countries.

It is highly likely that more species of Tranzscheliella await discovery as only 13 grass host species were included in our study. Our data showed that specimens from the same host species in different geographical regions were genetically closer than the specimens from the same geographical region on different hosts. This indicates the importance of host-adaption in the process of speciation. Cophylogenetic analyses showed that host switch was the best explanation for speciation in Tranzscheliella.

Materials and Methods

Specimens were borrowed from Queensland Plant Pathology Herbarium (BRIP) and Herbarium Mycologicum Academiae Sinicae (HMAS) (Table 1). Spores were mounted in lactic acid (100% v/v) and examined under the light microscope. Means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated from at least 20 measurements. Ranges were expressed as (min.−) mean − SD–mean + SD (−max.) with values rounded to 0.5 μm if below 20 μm and 1.0 μm if above 20 μm. Images were captured by using a Nikon Eclipse 80i camera attached to a Nikon DS-Fi1 compound microscope with Nomarski differential interference contrast. For scanning electron microscopy (SEM), dried spores were dusted onto double-sided adhesive tape, fixed on specimen stubs, sputter coated with gold, ca. 20 nm thick, and examined with a FEI Quanta 200 electron microscope. Nomenclatural novelties and descriptions were registered in MycoBank (www.MycoBank.org).

DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing

Fungal spores were removed from herbarium specimens with a fine needle and placed in cell lysis solution. For host tissue, dissected leaf samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground with a mortar and pestle. Genomic DNA was extracted with the Gentra Puregene® DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

ITS was amplified with the primers M-ITS 111 and ITS411,39. LSU was amplified with the primers LR0R/LR540. For the host plant, plasmid DNA regions rbcL, ITS and trnH-psbA were amplified with the primers rbcLa-F/rbcLa-R41,42, 17SE/26SE43 and psbAF/trnHR44, respectively. The PCR protocols were conducted as described by Zhang et al.45, with annealing temperature 62 °C for ITS of smuts, 60 °C for LSU, and 56 °C for ITS of host plants, rbcL and trnH-psbA. PCR products were sent to Biomed (Beijing, China) for sequencing with the same primer pairs used for amplification. Contigs were assembled in Mega 546.

Phylogenetic analyses

The DNA sequences included in this study (Table 1) were aligned online with MAFFT (mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/index.html) (Katoh and Toh 2008) using the L-INS-i method. ML was implemented as a search criterion in RAxML47 and PhyML 3.048. GTRGAMMA was specified as the model of evolution in both programs. The RAxML analyses were run with a rapid Bootstrap analysis (command -f a) using a random starting tree and 1,000 ML bootstrap replicates. The PhyML analyses were implemented using the ATGC bioinformatics platform (available at: http://www.atgcmontpellier.fr/phyml/), with six substitution type and SPR tree improvement, and support obtained from an approximate likelihood ratio test49.

MrBayes was used to conduct a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) search in a Bayesian analysis. Four runs, each consisting of four chains, were implemented until the standard deviation of split frequencies were 0.02. The cold chain was heated at a temperature of 0.25. Substitution model parameters were sampled every 1,000 generations and trees were saved every 1,000 generations. Convergence of the Bayesian analysis was confirmed using AWTY50 (available at: ceb.csit.fsu.edu/awty/).

Coalescent-based species delimitation

GMYC analysis

The combined ITS and LSU sequences were analysed under the single threshold model and the multi-threshold model. The alignments were stripped of non-unique haplotypes using Arlequin 3.151. Haplotype alignments were used to generate gene trees using Beast 1.7.5 with an uncorrelated lognormal relaxed clock model52 and nucleotide substitution model using the same parameters as in the Bayesian analysis. Four independent MCMC chains were run for 400,000,000 generations, with sampling every 10,000 generations, using the ‘auto optimize’ operators option, and a Yule tree prior. The effective sample size (ESS) of each run was determined using Tracer v1.5 and only trees with an ESS of at least 200 were kept53. Four separate tree files were combined by LogCombiner54 (burnin = 40,000) with a reduced resample frequency of 200,000. The reduced tree samples were used to reconstruct the maximum clade credibility tree by TreeAnnotator54. The selected topologies were used to optimize the single-threshold and multi-threshold GMYC models online (http://species.h-its.org/gmyc/).

PTP analysis

The RAxML gene trees were constructed using the same markers selected by GMYC analysis. The PTP analysis was conducted online (http://species.h-its.org/ptp/) with the following settings: 10,000 MCMC generations; thinning interval of 100 and burn-in of 0.234.

Cospeciation analyses

TREEMAP 3b55 was used to generate a tanglegram from the ML tree of Tranzscheliella spp. and their host plants. To assess cospeciation between the host and parasites, both distance-based and event-based methods were utilized for the cophylogenetic analyses. For each of these two analyses, the parasite topology was obtained by using PhyML analysis based on ITS and LSU alignment, including just one representative per putative species. The host topology was obtained by PhyML analysis based on rbcL, ITS and trnH-psbA alignment of the representative specimens. For the distance-based analyses of cophylogeny, COPYCAT 2.0256 was used, which incorporated a wrapper for ParaFit57. The congruence between the host and parasites phylogenies were computed and statistical significance tests were assessed by comparing randomizing parasites and host association with 999 permutations58,59. Event-based analyses were run in Jane 460.

Jane 4 considers five types of co-evolutionary event, namely cospeciation, duplication, host switch, sorting and failure to diverge. As it is difficult to estimate the relative cost of events, a default event cost scheme (cospeciation = 0, duplication = 1, duplication and host switch = 2, sorting = 1, failure to diverge = 1) as well as 9 cost regimes derived from default one were tested. In all the analyses, the vertex-base cost model method has been implemented, with the number of generation has been set to 100, and population size to 300. And the statistical significance of reconstructions was evaluated with 1,000 random tip mapping permutations.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Li, Y.-M. et al. Cryptic diversity in Tranzscheliella spp. (Ustilaginales) is driven by host switches. Sci. Rep. 7, 43549; doi: 10.1038/srep43549 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Alistair R. McTaggart, Marjan Shivas, Yu Pei Tan and Yu Zhang for help collecting specimens. Dr. Peng Zhao and Dr. Fang Liu are thanked for technical assistance. This study was financially supported by Fundamental Research on Science and Technology, MOST (2014FY120100), CAS (QYZDB-SSW-SMC044) and NSFC 31110103906.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Y.M. Li, R.G. Shivas and L. Cai designed the study. Y.M. Li performed all the experiments and statistical analyses. Y.M. Li, R.G. Shivas and L. Cai edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the manuscript for publication.

References

- Vánky K. Smut Fungi of the World (APS Press St. Paul, Minnesota, USA [‘2012’] 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Vánky K. Illustrated Genera of Smut Fungi 3rd Edition (APS Press: St. Paul, Minnesota, USA 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Lavrov N. Ustilaginaceae novae vel rarae Asiae borealis centralisque. Trundy Biol. Naučno-Issl. Inst. Tomsk. Gosud. Univ 2, 1–35 (1936). [Google Scholar]

- Vánky K. Taxonomical studies on Ustilaginales. XXIII. Mycotaxon 85, 1–65 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Vánky K. The smut fungi (Ustilaginomycetes) of Sporobolus (Poaceae). Fungal Divers. 14, 205–241 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Begerow D., Stoll M. & Bauer R. A phylogenetic hypothesis of Ustilaginomycotina based on multiple gene analyses and morphological data. Mycologia 98, 906–916 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q. M. et al. Multigene phylogeny and taxonomic revision of yeasts and related fungi in the Ustilaginomycotina. Stud. Mycol. 81, 55–83 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vánky K. & McKenzie E. H. Smut fungi of New Zealand. (Fungal Diversity Press, University of Hong Kong, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- Fischer G. W. & Hirschhorn E. A critical study of some species of Ustilago causing stem smut on various grasses. Mycologia 37, 236–266 (1945). [Google Scholar]

- Begerow D. et al. Ustilaginomycotina in The Mycota, Systematics and Evolution Vol. 7A (eds McLaughlin, D.J., Spatafora, J.W.) 299–330 (Springer, Berlin, 2014).

- Stoll M., Piepenbring M., Begerow D. & Oberwinkler F. Molecular phylogeny of Ustilago and Sporisorium species (Basidiomycota, Ustilaginales) based on internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences. Can. Bot. 81, 976–984 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Stoll M., Begerow D. & Oberwinkler F. Molecular phylogeny of Ustilago, Sporisorium, and related taxa based on combined analyses of rDNA sequences. Mycol. Res. 109, 342–356 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L. et al. The evolution of species concepts and species recognition criteria in plant pathogenic fungi. Fungal Divers. 50, 121–133 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- McTaggart A. R. Shivas R. G., Geering A. D. W., Vánky K. & Scharaschkin T. Taxonomic revision of Ustilago, Sporisorium and Macalpinomyces. Persoonia 29, 116–132 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Losada M. et al. Comparing phylogenetic codivergence between polyomaviruses and their hosts. J. Virol. 80, 5663–5669 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J. E. & Hafner M. S. Codivergence in heteromyid rodents (Rodentia: Heteromyidae) and their sucking lice of the genus Fahrenholzia (Phthiraptera: Anoplura). Syst. Biol. 57, 449–465 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refrégier G. et al. Cophylogeny of the anther smut fungi and their caryophyllaceous hosts: prevalence of host shifts and importance of delimiting parasite species for inferring cospeciation. BMC Evol. Biol. 8, 1 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTaggart A. R. et al. Host jumps shaped the diversity of extant rust fungi (Pucciniales). New Phytol. 209, 1149–1158 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escudero M. Phylogenetic congruence of parasitic smut fungi (Anthracoidea, Anthracoideaceae) and their host plants (Carex, Cyperaceae): Cospeciation or host-shift speciation? Am. J. Bot. 102, 1108–1114 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlechtendal D. F. L. Flora Berolinensis, Pars 2. Cryptogamia. Berlin. XIV (1824).

- Hirschhorn E. Critical observations on the Ustilaginaceae. Farlowia 3, 73 (1947). [Google Scholar]

- Hamasha H. R., Von Hagen K. B. & Roser M. Stipa (Poaceae) and allies in the Old World: molecular phylogenetics realigns genus circumscription and gives evidence on the origin of American and Australian lineages. PLANT SYST EVOL 298, 351–367 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Lavrov N. Ustilagineae novae vel rarae Asiae septentrionalis. Trudy Tomsk. Gosud. Univ. 80, 83–87 (1934). [Google Scholar]

- Vánky K. Carpathian Ustilaginales. Acta Univ. Upsal., Symb. Bot. Upsal 24, 1–39 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- Saarela J. M. et al. Phylogenetics of the grass ‘Aveneae-type plastid DNA clade’(Poaceae: Pooideae, Poeae) based on plastid and nuclear ribosomal DNA sequence data. In Seberg O., Petersen G., Barfod A. S., Davis J. eds Diversity, phylogeny, and evolution in the monocotyledons Aarhus, Denmark, Aarhus University Press, 557–586 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Lindegerg B. Ustilaginales of Sweden. Acta Univ. Upsal., Symb. Bot. Upsal 16, 1–175 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- Cialdella A. M. et al. Phylogeny of Nassella (Stipeae, Pooideae, Poaceae) based on analyses of chloroplast and nuclear ribosomal DNA and morphology. Syst. Bot. 39, 814–828 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Spegazzini C. L. Nova addenda ad floram Patagonicam. Anales Mus. Nac. Buenos Aires 7, 135–308 (1902). [Google Scholar]

- Hirschhorn E. Una nueva especie de Ustilago de la flora Argentina. Notas Mus. La Plata, Bot. 4, 415–419 (1939). [Google Scholar]

- Fan X. et al. Phylogeny and evolutionary history of Leymus (Triticeae; Poaceae) based on a single-copy nuclear gene encoding plastid acetyl-CoA carboxylase. BMC Evol. Biol. 9 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R. R. C. Chapter 2. Agropyron and Psathyrostachys In Chittaranjan Kole (ed.) Wild Crop Relatives: Genomic and Breeding, 77–108 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Pons J. et al. Sequence-based species delimitation for the DNA taxonomy of undescribed insects. Syst. Biol. 55, 595–609 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontaneto D. et al. Independently Evolving Species in Asexual Bdelloid Rotifers. PLoS. Biol. 5, e87 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Kapli P., Pavlidis P. & Stamatakis A. A general species delimitation method with applications to phylogenetic placements. Bioinformatics 29, 2869–2876 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa T. & Barraclough T. G. Delimiting species using single-locus data and the Generalized Mixed Yule Coalescent approach: a revised method and evaluation on simulated data sets. Syst. Biol. 62, 707–724 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedin M. High‐stakes species delimitation in eyeless cave spiders (Cicurina, Dictynidae, Araneae) from central Texas. Mol. Ecol. 24, 346–361 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTaggart A. R. et al. Soral synapomorphies are significant for the systematics of the Ustilago-Sporisorium-Macalpinomyces complex (Ustilaginaceae). Persoonia 29, 63–77 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTaggart A. R., Shivas R. G., Geering A. D. W., Vanky K. & Scharaschkin T. A review of the Ustilago-Sporisorium-Macalpinomyces complex. Persoonia 29, 55–62 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White T. J., Bruns T., Lee S. & Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications 18, 315–322 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- Vilgalys R. & Hester M. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J. Bacteriol. 172, 4238–4246 (1990). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin R. A. et al. Family-level relationships of Onagraceae based on chloroplast rbcL and ndhF data. Am. J. Bot. 90, 107–115 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kress W. J. et al. Plant DNA barcodes and a community phylogeny of a tropical forest dynamics plot in Panama. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 18621–18626 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y., Skinner D., Liang G. & Hulbert S. Phylogenetic analysis of Sorghum and related taxa using internal transcribed spacers of nuclear ribosomal DNA. Theor. Appl. Genet. 89, 26–32 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sang T., Crawford D. & Stuessy T. Chloroplast DNA phylogeny, reticulate evolution, and biogeography of Paeonia (Paeoniaceae). Am. J. Bot. 84, 1120–1136 (1997). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Zhang N. & Cai L. Typification and phylogenetic study of Phyllosticta ampelicida and P. vaccinii. Mycologia 105, 1030–1042 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K. & Toh H. Recent developments in the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Brief. Bioinform. 9, 286–298 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S. et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anisimova M. et al. Survey of branch support methods demonstrates accuracy, power, and robustness of fast likelihood-based approximation schemes. Syst. Biol. syr041 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylander J. A., Wilgenbusch J. C., Warren D. L. & Swofford D. L. AWTY (are we there yet?): a system for graphical exploration of MCMC convergence in Bayesian phylogenetics. Bioinformatics 24, 581–583 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L., Guillaume L. & Schneider S. Arlequin ver. 3.0: An integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. pp. 47–50 Evol. Bioinform. Online (2005). [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Drummond A. J., Ho S. Y., Phillips M. J. & Rambaut A. Relaxed phylogenetics and dating with confidence. PLoS Biol 4, e88 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J., Suchard M. A., Xie D. & Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1969–1973 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A. J. & Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 214 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charleston M. TreeMap 3b. URL http://sites. google. com/site/cophylogeny (2011).

- Meier-Kolthoff J. P., Auch A. F., Huson D. H. & Goker M. COPYCAT: cophylogenetic analysis tool. Bioinformatics 23, 898–900 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre P., Desdevises Y. & Bazin E. A statistical test for host–parasite coevolution. Syst. Biol. 51, 217–234 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. et al. Genetic diversity of Ophiocordyceps sinensis, a medicinal fungus endemic to the Tibetan Plateau: implications for its evolution and conservation. BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 290 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millanes A. M. et al. Host switching promotes diversity in host-specialized mycoparasitic fungi: uncoupled evolution in the Biatoropsis-usnea system. Evolution 68, 1576–1593 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conow C., Fielder D., Ovadia Y. & Libeskind-Hadas R. Jane: a new tool for the cophylogeny reconstruction problem. Algorithms. Mol. Biol. 5, 16 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]