Abstract

Treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile–associated diarrhea can be challenging. Once patients develop recurrent disease, further episodes are common and can continue for months or even a year or more. Treatment begins with a repeat standard 10-day course of antibiotics, followed by tapering and/or pulsing of the antibiotic dose. Probiotics can also be useful, particularly the nonpathogenic yeast Saccharomyces boulardii. Stool reconstitution via fecal enemas, colonoscopy, and nasogastric tubes have been performed to restore normal colonic flora. Additional approaches under investigation, such as vaccination against C. difficile, show encouraging preliminary results.

Keywords: Recurrent Clostridium difficile–associated disease, vancomycin, metronidazole, Saccharomyces boulardii, Lactobacillus GG

Clostridium difficile is a Gram-positive anaerobic bacillus that is the most common cause of nosocomial diarrhea, resulting in substantial morbidity and mortality. Transmission occurs via the fecal-oral route by ingestion of spores that germinate into bacteria. Colonization usually occurs after the normal flora has been disrupted by antibiotic therapy, although sporadic cases can occur.1 The bacterium produces two toxins, A and B, that are responsible for the ensuing diarrhea and colitis. Recent epidemics have been associated with a fluoroquinolone-resistant strain that produces a binary toxin, the significance of which is unclear.2,3 The spectrum of disease ranges from asymptomatic carriage to severe pseudomembranous colitis, often occurring 1–2 weeks after the initiation of antibiotic therapy.

Although patients with an initial episode of C. difficile–associated disease (CDAD) usually respond to antibiotic therapy, 20–35% of patients will develop recurrent disease.4-6 Most recurrences occur within 5–8 days of completion of therapy. Once recurrent C. difficile–associated disease (RCDAD) develops, 45–65% of patients will have repeated episodes that can continue for months or, rarely, for several years.7,8 Risk factors for recurrent disease include continued use of antibiotics, advanced age, female sex, and renal disease.4,9 The pathophysiology is not fully defined, but may be explained by an inability of the normal flora to repopulate the colon and suppress overgrowth of C. difficile or by an inadequate immune response or both. Although the term “relapse” implies the presence of the same strain, studies comparing C. difficile strains from initial and recurrent episodes have shown that in 25–67% of cases the recurrent strain is a different one.5,10-12 It is likely that other factors affect the likelihood of recurrence, including the abnormal flora and an altered host immune response.

The diagnosis of RCDAD is based on the detection of C. difficile and/or toxin in the stool of patients with diarrhea that recurs after completion of the initial antibiotic for CDAD. Symptoms can be severe, and approximately 6–10% of patients with RCDAD are hospitalized during serious episodes. In this situation other causes of diarrhea, although uncommon, should be considered. Postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome can contribute to chronic diarrhea syndromes, as can postinfectious inflammatory bowel disease or microscopic colitis.

Treatment of RCDAD presents a challenge. Once a patient has a recurrence, the chance of future recurrences is markedly increased,4 and there is no uniformly effective therapy. Current treatment options include repeat antibiotics, which should be given to all patients, as well as several microbiological and immune approaches for adjunctive therapy.

Repeat Antibiotics

An initial approach to RCDAD involves the use of antibiotics, typically metronidazole 250 mg orally four times daily for 10 days, or vancomycin 125–500 mg orally four times daily for 10 days. Rifampin is occasionally used as adjunctive therapy, although no controlled studies have demonstrated superiority.13 It is important to realize that recurrence is not due to resistance of the organism to the treating antibiotic. Recurrences are decreased by tapering or pulsing antibiotics. With tapering, doses are gradually decreased over a period of several days. Due to the possibility of developing irreversible peripheral neurotoxicity with long-term metronidazole, vancomycin is often preferred. Pulse therapy involves alternating antibiotics with days off of therapy, which occur at increasing intervals. A combination approach is to taper antibiotic doses initially over 2–3 days after the initial 10-day treatment, followed by pulse therapy at that dose for several weeks. In one study of 163 patients with RCDAD, recurrences occurred in 40–71% of patients following a 10- to 14-day course of antibiotics, compared to recurrence rates of 31% with a tapering regimen, 14% with pulsing, and 20% with a combination approach.14

A sample antibiotic regimen for RCDAD might consist of vancomycin 500 mg four times daily for 10 days, followed by a lower dose of 125 or 250 mg twice daily every other day for a week, then every third day, etc. Once antibiotics are taken only every tenth day, recurrences are unlikely and antibiotics can be discontinued.

Probiotics

The term “probiotic” refers to a microorganism whose ingestion leads to a beneficial therapeutic effect, in this case by presumably allowing the normal flora to repopulate and suppress overgrowth of C. difficile. Proposed mechanisms by which this might occur include competition for nutrients, stimulation of immunity, inhibition of mucosal adherence, and production of antimicrobial substances.15 Probiotics have gained popularity, initially in Europe and more recently in the United States. Both bacteria and yeast have been used in the treatment of RCDAD, although only the yeast Saccharomyces boulardii has been shown to be effective in randomized controlled trials.

Saccharomyces boulardii

S. boulardii is a nonpathogenic yeast with an unusual optimum growth temperature of 37°C. It survives passage through the gastrointestinal tract, and reaches steady-state levels in the stool of human volunteers within 3–5 days.16 Oral administration is well tolerated, and it has been used in Europe for many years for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Several controlled trials have shown efficacy in this setting.17-19 In a hamster model of RCDAD, S. boulardii was found to prevent recurrence of clindamycin-induced cecitis.20 These results prompted the enrollment of 14 patients with RCDAD into an open-label trial of S. boulardii plus vancomycin. Of the 13 patients that completed the study, 11 (85%) had no further recurrences.21 Subsequently a randomized controlled trial was performed in which S. boulardii was given with vancomycin or metronidazole to 64 patients with an initial episode of CDAD and 60 patients with RCDAD. Treatment resulted in no significant improvement in patients with initial CDAD, but decreased recurrences by almost 50% in those with recurrent disease.22 Neither the dose nor duration of antibiotics was controlled for in this study.

In a later trial, patients received a standard 10-day regimen of high-dose vancomycin (2 g/day), low-dose vancomycin (500 mg/day), or metronidazole (1 g/day) plus either S. boulardii or placebo. A significant reduction in recurrences was seen only in the group receiving S. boulardii and high-dose vancomycin.23 One explanation might be improved clearance of C. difficile from the stool by high-dose vancomycin. In fact, treatment with high-dose vancomycin completely cleared C. difficile by the end of the 10-day course of antibiotic therapy, whereas the other antibiotic regimens did not. Similar results have been reported elsewhere, with C. difficile clearance in 89% of patients receiving vancomycin versus 59% of those treated with metronidazole.14 Another potential explanation is the protease produced by S. boulardii, which inactivates C. difficile toxin receptors and results in proteolytic digestion of toxins A and B.24,25 The authors hypothesized that by preventing binding of C. difficile toxin, this protease might allow for restoration of the normal intestinal microflora and reestablishment of colonization resistance. Other potential mechanisms of action of the S. boulardii protease have been suggested by animal studies, which show diminished ileal fluid secretion in rats exposed to C. difficile toxin A25 and stimulation of the intestinal immunoglobulin (Ig) A response to toxin A in mice.26

Lactobacillus

Lactobacillus GG has several characteristics that make it an appealing probiotic. It is resistant to acid and bile, allowing it to survive passage through the gastrointestinal tract.27 It adheres to intestinal epithelial cells and produces an antimicrobial substance that inhibits a broad range of bacteria, including C. difficile.28 Uncontrolled trials have suggested efficacy in RCDAD. In one report, 4 out of 5 patients had an immediate response to therapy and had no further relapses. The fifth patient required two courses of Lactobacillus GG to achieve cure.29 Additional uncontrolled trials reported cure in 2 out of 4 children30 and 5 out of 9 adults.31 Although a preliminary report of a controlled trial also suggested efficacy, no final report has been published.32 A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the addition of Lactobacillus plantarum 299v to metronidazole therapy was not adequately powered to show a significant benefit; recurrence occurred in 4 out of 11 patients receiving combination therapy, compared to 6 out of 9 patients receiving metronidazole and placebo.33

Fecal Enemas and Stool Repopulation

Several reports have described the use of stool donation in an attempt to replenish the colon with healthy bacteria. In one of the earliest reports, Bowden and colleagues34 suggested that bacterial overgrowth plays an important role in the development of pseudomembranous colitis, and postulated that restoration of fecal floral homeostasis could lead to resolution of disease. In this study, 16 patients who had failed standard therapy for pseudomembranous enterocolitis were treated with fecal enemas derived from the stool of family members or other healthy volunteers. Thirteen had a dramatic clinical response with no reported side effects. The remaining three patients died. Of these three, two did not have pseudomembranes at death, and one had small bowel involvement.

Other authors have used a similar approach for RCDAD. Schwan and colleagues35 reported successful treatment of RCDAD by rectal infusion of normal feces in a woman who had experienced multiple relapses of C. difficile colitis. Persky and Brandt36 reported success in another patient, using infusion of stool donated from the patient’s husband and injected at 10 cm intervals throughout the colon during colonoscopy. They hypothesized that polyethylene glycol and electrolyte solution (Golytely, Braintree) preparation may have helped as well by allowing elimination of residual C. difficile organisms and spores before stool administration. They also suggested that administration during colonoscopy may be more effective than by enema, due to the ability to administer organisms proximal to the splenic flexure.

Donor stool has also been administered via nasogastric tube into the stomach. Aas and associates37 performed a retrospective review of 18 patients treated in this manner over a 9-year period. Patients were pretreated with at least 4 days of oral vancomycin. In the subsequent 90 days following stool transplantation, 2 patients died of unrelated illnesses, and only 1 of the remaining patients experienced recurrence of C. difficile colitis.

Rectal Instillates of Microbes

Tvede and Rask-Madsen38 studied 6 patients with chronic RCDAD, and found that rectal instillation of a mixture of facultative aerobic and anaerobic bacteria led to loss of C. difficile and its toxin from the stools.38 It also led to bowel colonization by Bacteroides species, which had not been present in pretreatment stool samples. This suggests that Bacteroides may play a role in maintaining the normal intestinal milieu.

Nontoxigenic Strains of C. difficile

Borriello and Barclay36 studied the use of nontoxigenic strains of C. difficile using a hamster model of RCDAD. Hamsters pretreated with nontoxigenic strains prior to clindamycin therapy were protected against the development of C. difficile diarrhea.39 Most of the protected hamsters survived for up to 27 days, compared to none of the controls. These strains were later given orally to two humans with RCDAD, with resolution of their symptoms.40 However, a recent report of nontoxigenic strains of C. difficile among hospitalized patients with diarrhea suggests that nontoxigenic strains may also cause diarrhea, making this treatment approach less appealing.41

Toxin Binders

Another adjunctive therapeutic approach is the use of anion exchange resins, including cholestyramine and colestipol, in an attempt to bind C. difficile toxins. Efficacy of these agents in toxin binding has not been clearly established. Anion exchange resins have been given to patients with pseudomembranous colitis with variable response.42-44 In RCDAD, colestipol was given in combination with tapering doses of vancomycin to 11 patients, with resolution of symptoms and no recurrence for at least 6 weeks.45 Because these agents can also bind antimicrobials, they should not be given within 2–3 hours of antibiotic ingestion. Synthetic toxin binders have also been studied, and have been shown to have efficacy in binding C. difficile toxins,46-47 but are still in clinical trials.

Immune Approaches

Immune approaches to the treatment of RCDAD have included both active and passive immunization against C. difficile.48 This concept stems from studies that suggest a defective humoral response to the organism in patients with recurrent disease. Warny and coworkers49 found that patients with RCDAD had significantly lower serum IgG and fecal IgA antitoxin A titers than did patients suffering a single episode. Antibody levels also appeared to affect the duration of symptoms, such that patients with symptoms lasting more than 2 weeks had significantly lower antibody levels than those with symptoms of shorter duration. Aronsson and associates50 found a correlation between high IgG titers to toxin B and clinical recovery without relapse. In a study of 6 children with RCDAD, Leung and colleagues51 found lower IgG antitoxin A levels in those with relapsing disease.

Further evidence suggests that the immune response may determine whether patients with nosocomial infection develop diarrhea or remain asymptomatic. Kyne and colleagues52 studied antibody response to C. difficile toxin and found that although antibody levels did not correlate with the likelihood of colonization, patients who remained asymptomatic carriers had significantly higher serum levels of IgG antibody against toxin A than patients that developed diarrhea. This group later reported that patients with RCDAD had lower concentrations of serum IgM against toxin A on day 3 and of IgG to toxin A on day 12 after the onset of symptoms.53 Thus, it appears that serum antibodies to toxin A provide protection from C. difficile diarrhea and from the development of recurrent disease in humans.

Therapeutic measures have included active and passive vaccination. Aboudola et al54 developed a parenteral vaccine to inactivated toxins A and B, and showed that it led to high antibody levels in healthy volunteers. The vaccine was then given in combination with vancomycin to three patients with multiple episodes of RCDAD without further recurrence.55

Another approach is passive immunization using intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG). This has been given with success to 5 children with RCDAD.51 Patients responded with significant increases in IgG antitoxin A levels and clinical resolution of gastrointestinal symptoms. Success has also been reported with IVIG in adults.56,57 Wilcox58 treated 5 patients with protracted or recurrent CDAD using IVIG at doses of 300–500 mg/kg. Three had a good response, 1 had recurrence, and 1 died of intractable CDAD.

Oral antibodies may also be effective. Immunoglobulins derived from the colostrum of cows immunized with C. difficile toxoids have been found to neutralize the effects of toxins A and B in vitro, and to inhibit enterotoxic effects in the rat ileum.59 In hamsters, these immunoglobulins prevent diarrhea and subsequent death.60 Avian antibodies against recombinant toxins have also been shown to be effective in a hamster model.61 In a recent pilot study in humans, whey protein concentrate (WPC) containing high concentrations of IgA antibodies derived from the milk of C. difficile–immunized cows was given to 16 patients with CDAD. Nine of these patients had RCDAD. Patients were treated with standard antibiotics followed by WPC for 2 weeks, and none suffered further episodes of diarrhea.62 A randomized controlled trial using WPC is underway.

Bowel Irrigation

Whole-bowel irrigation with polyethylene glycol solution was given to two children with RCDAD who had failed several therapeutic regimens.63 Treatment was followed by a 3-week course of oral vancomycin and Lactobacillus therapy. Both patients had a prompt response and no further recurrences. The authors postulated that whole-bowel irrigation cleared the intestine of C. difficile organisms, toxins, and spores. The extent to which the clinical response may have been due to polyethylene glycol remains unclear.

Conclusion

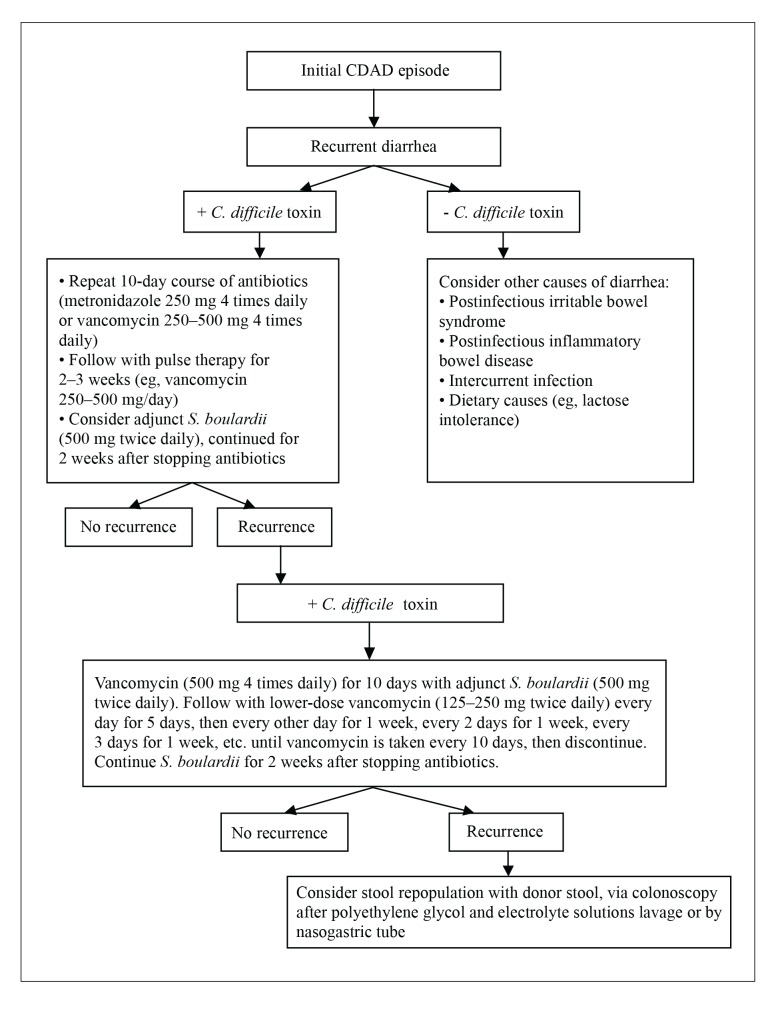

Treatment of RCDAD remains a challenge, although recent developments are encouraging. A therapeutic strategy for RCDAD might consist of a 10-day course of high-dose vancomycin (2 g/day) followed by pulse dosing at lower doses (250–500 mg/day), with gradually increasing intervals between days on and days off antibiotics (Figure 1). Efficacy can be improved by adding S. boulardii (500 mg twice daily) and continuing it for 2 weeks after cessation of antibiotics. If this is unsuccessful, a second attempt can be considered. Stool donation via colonoscopy is an option in the case of continued recurrence, although this approach has not been studied in controlled trials. Future treatment strategies may also incorporate immune approaches such as vaccination against C. difficile.

Figure 1.

Treatment strategy for recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated disease.

CDAD = C. difficile-associated disease; S. boulardii = Saccharomyces boulardii.

References

- 1.Moskovitz M, Bartlett JG. Recurrent pseudomembranous colitis unassociated with prior antibiotic therapy. Ann Intern Med. 1981;141:663–664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, et al. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2433–2441. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loo VG, Poirier L, Miller MA, et al. A predominantly clonal multi-institutional outbreak of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea with high morbidity and mortality. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2442–2449. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fekety R, McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, et al. Recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhea: characteristics of and risk factors for patients enrolled in a prospective, randomized, double-blinded trial. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:324–333. doi: 10.1093/clinids/24.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barbut F, Richard A, Hamadi K, et al. Epidemiology of recurrences or reinfections of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:2386–2388. doi: 10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.t031141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilcox MH. Treatment of Clostridium difficile infection. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41(3):41–46. doi: 10.1093/jac/41.suppl_3.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerding DN. Treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2000;250:127–139. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-06272-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, Rubin M, et al. Recurrent Clostridium difficile disease: epidemiology and clinical characteristics. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:43–50. doi: 10.1086/501553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Do AN, Fridkin SK, Yechouron A, et al. Risk factors for early recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:954–959. doi: 10.1086/513952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Neill GL, Beaman MH, Riley TV. Relapse versus reinfection with Clostridium difficile. Epidemiol Infect. 1991;107:627–635. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800049323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson S, Adelman A, Clabots CR, et al. Recurrences of Clostridium difficile diarrhea not caused by the original infecting organism. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:340–343. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang-Feldman Y, Mayo S, Silva J, et al. Molecular analysis of Clostridium difficile strains isolated from 18 cases of recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:3413–3414. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.7.3413-3414.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buggy BP, Fekety R, Silva J. Therapy of relapsing Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea and colitis with the combination of vancomycin and rifampin. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;9:155–159. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198704000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McFarland LV, Elmer GW, Surawicz CM. Breaking the cycle: treatment strategies for 163 cases of recurrent Clostridium difficile disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1769–1775. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05839.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rolfe RD. The role of probiotic cultures in the control of gastrointestinal health. J Nutr. 2000;183:396S–402S. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.2.396S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blehaut H, Massot J, Elmer GW, et al. Disposition kinetics of Saccharomyces boulardii in man and rat. Biopharm Drug Dispos. 1989;10:353–364. doi: 10.1002/bdd.2510100403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adam J, et al. Essai’s cliniques contrôlés en double insu de l’ultra-levure lyophilisée. Étude multicentrique par 25 medecins de 388 cas. Gaz Med Fr. 1977;84:2072–2081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surawicz CM, Elmer GW, Speelman P, et al. Prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea by Saccharomyces boulardii: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:981–988. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)91613-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, Greenberg RN, et al. Prevention of β-lactam-associated diarrhea by Saccharomyces boulardii compared with placebo. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:439–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elmer GW, McFarland LV. Suppression by Saccharomyces boulardii of toxigenic Clostridium difficile overgrowth after vancomycin treatment in hamsters. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:129–131. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Surawicz CM, McFarland LV, Elmer G, et al. Treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis with vancomycin and Saccharomyces boulardii. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1285–1287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McFarland LV, Surawicz CM, Greenberg RN, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of Saccharomyces boulardii in combination with standard antibiotics for Clostridium difficile disease. JAMA. 1994;271:1913–1918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Surawicz CM, McFarland LV, Greenberg RN, et al. The search for a better treatment for recurrent Clostridium difficile disease: use of high-dose vancomycin combined with Saccharomyces boulardii. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1012–1017. doi: 10.1086/318130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Castagliuolo I, Riegler MF, Valenick L, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii protease inhibits the effects of Clostridium difficile toxins A and B in human colonic mucosa. Infect Immun. 1999;67:302–307. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.302-307.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pothoulakis C, Kelly CP, Joshi MA, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii inhibits Clostridium difficile toxin A binding and enterotoxicity in rat ileum. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1108–1115. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90280-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qamar A, Aboudola S, Warny M, et al. Saccharomyces boulardii stimulates intestinal immunoglobulin A immune response to Clostridium difficile toxin A in mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2762–2765. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.4.2762-2765.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldin BR, Gorbach SL, Saxelin M, et al. Survival of Lactobacillus species (strain GG) in human gastrointestinal tract. Dig Dis Sci. 1992;37:121–128. doi: 10.1007/BF01308354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silva M, Jacobus NV, Deneke C, et al. Antimicrobial substance from a human Lactobacillus strain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1231–1233. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.8.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorbach SL, Chang TW, Goldin B. Successful treatment of relapsing Clostridium difficile colitis with Lactobacillus GG. Lancet. 1987;2:1519. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92646-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Biller JA, Katz AJ, Flores AF, et al. Treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis with Lactobacillus GG. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1995;21:224–226. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199508000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennet RG, Laughon B, Lindsay J, et al. Lactobacillus GG treatment of Clostridium difficile infection in nursing home patients; Abstract of the Third International Conference on Nosocomial Infection; Atlanta, Georgia. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pochapin M. The effect of probiotics on Clostridium difficile diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:S11–S13. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(99)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wullt M, Hagslätt MJ, Odenholt I. Lactobacillus plantarum 299v for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Scand J Infect Dis. 2003;35:365–367. doi: 10.1080/00365540310010985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bowden TA, Mansberger AR, Lykins LE. Pseudomembraneous enterocolitis: mechanism of restoring floral homeostasis. Am J Surg. 1981;47:178–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schwan A, Sjölin S, Trottestam U, et al. Relapsing Clostridium difficile enterocolitis cured by rectal infusion of normal faeces. Scand J Infect Dis. 1984;16:211–215. doi: 10.3109/00365548409087145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Persky SE, Brandt LJ. Treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea by administration of donated stool directly through a colonoscope. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3283–3285. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.03302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aas J, Gessert CE, Bakken JS. Recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis: case series involving 18 patients treated with donor stool administered via a nasogastric tube. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:580–585. doi: 10.1086/367657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tvede M, Rask-Madsen J. Bacteriotherapy for chronic relapsing Clostridium difficile diarrhoea in six patients. Lancet. 1989;1(8648):1156–1160. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92749-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Borriello SP, Barclay FE. Protection of hamsters against Clostridium difficile ileocaecitis by prior colonisation with non-pathogenic strains. J Med Microbiol. 1985;19:339–350. doi: 10.1099/00222615-19-3-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seal D, Borriello SP, Barclay F, et al. Treatment of relapsing Clostridium difficile diarrhoea by administration of a non-toxigenic strain. Eur J Clin Microbiol. 1987;6:51–53. doi: 10.1007/BF02097191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martirosian G, Szczesny A, Cohen SH, Silva J., Jr Analysis of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea among patients hospitalized in tertiary care academic hospital. Diagnostic Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;52:153–155. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kreutzer EW, Milligan FD. Treatment of antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis with cholestyramine resin. Johns Hopkins Med J. 1978;143:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tedesco FJ, Napier J, Gamble W, et al. Therapy of antibiotic associated pseudomembranous colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1979;1:51. doi: 10.1097/00004836-197903000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keighley MRB. Antibiotic associated pseudomembranous colitis: pathogenesis and management. Drugs. 1980;20:49–56. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198020010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tedesco FJ. Treatment of recurrent antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77:220–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heerze LD, Kelm MA, Talbot JA, et al. Oligosaccharide sequences attached to an inert support (SYNSORB) as potential therapy for antibiotic-associated diarrhea and pseudomembranous colitis. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:291–296. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.6.1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braunlin W, Xu Q, Hook P, et al. Toxin binding of tolevamer, a polyanionic drug that protects against antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Biophys J. 2004;87:534–539. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.041277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giannasca PJ, Warny M. Active and passive immunization against Clostridium difficile diarrhea and colitis. Vaccine. 2004;22:848–856. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2003.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warny M, Vaerman JP, Avesani V, et al. Human antibody response to Clostridium difficile toxin A in relation to clinical course of infection. Infect Immun. 1994;62:384–389. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.384-389.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aronsson B, Granström M, Möllby R, et al. Serum antibody response to Clostridium difficile toxins in patients with Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Infection. 1985;13:97–101. doi: 10.1007/BF01642866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leung DYM, Kelly CP, Boguniewicz M, et al. Treatment with intravenously administered gamma globulin of chronic relapsing colitis induced by Clostridium difficile toxin. J Pediatr. 1991;118:633–637. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(05)83393-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, et al. Asymptomatic carriage of Clostridium difficile and serum levels of IgG antibody against toxin A. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:390–397. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kyne L, Warny M, Qamar A, et al. Association between antibody response to toxin A and protection against recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Lancet. 2001;357:189–193. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03592-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aboudola S, Kotloff KL, Kyne L, et al. Clostridium difficile vaccine and serum immunoglobulin G antibody response to toxin A. Infect Immun. 2003;71:1608–1610. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.3.1608-1610.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sougioultzis S, Kyne L, Drudy D, et al. Clostridium difficile toxoid vaccine in recurrent C. difficile-associated diarrhea. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:764–770. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Salcedo J, Keates S, Pothoulakis C, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for severe Clostridium difficile colitis. Gut. 1997;41:366–370. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.3.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beales ILP. Intravenous immunoglobulin for recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. Gut. 2002;51:456. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.3.456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilcox MH. Descriptive study of intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile diarrhoea. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53:882–884. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kelly CP, Pothoulakis C, Vavva F, et al. Anti-Clostridium difficile bovine immunoglobulin concentrate inhibits cytotoxicity and enterotoxicity of C. difficile toxins. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:373–379. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.2.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lyerly DM, Bostwick EF, Binion SB, et al. Passive immunization of hamsters against disease caused by Clostridium difficile by use of bovine immunoglobulin G concentrate. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2215–2218. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.2215-2218.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.King JA, Williams JA. Antibodies to recombinant Clostridium difficile toxins A and B are an effective treatment and prevent relapse of C. difficile-associated disease in a hamster model of infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2018–2025. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2018-2025.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Dissel JT, De Groot N, Hensgens CM, et al. Bovine antibody-enriched whey to aid in the prevention of a relapse of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: preclinical and preliminary clinical data. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54(pt 2):197–205. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45773-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liacouras CA, Piccoli DA. Whole-bowel irrigation as an adjunct to the treatment of chronic, relapsing Clostridium difficile colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996;22:186–189. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199604000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]