Abstract

In this study, we first performed whole exome sequencing of DNA from 10 untreated and clinically annotated fresh frozen nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) biopsies and matched bloods to identify somatically mutated genes that may be amenable to targeted therapeutic strategies. We identified a total of 323 mutations which were either non-synonymous (n = 238) or synonymous (n = 85). Furthermore, our analysis revealed genes in key cancer pathways (DNA repair, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, immune response, lipid signaling) were mutated, of which those in the lipid-signaling pathway were the most enriched. We next extended our analysis on a prioritized sub-set of 37 mutated genes plus top 5 mutated cancer genes listed in COSMIC using a custom designed HaloPlex target enrichment panel with an additional 88 NPC samples. Our analysis identified 160 additional non-synonymous mutations in 37/42 genes in 66/88 samples. Of these, 99/160 mutations within potentially druggable pathways were further selected for validation. Sanger sequencing revealed that 77/99 variants were true positives, giving an accuracy of 78%. Taken together, our study indicated that ~72% (n = 71/98) of NPC samples harbored mutations in one of the four cancer pathways (EGFR-PI3K-Akt-mTOR, NOTCH, NF-κB, DNA repair) which may be potentially useful as predictive biomarkers of response to matched targeted therapies.

Targeted therapies with higher selectivity and minimal toxicity are now frequently used as standard-of-care for treating several human cancers that include lung1, breast2 and colorectal3 harboring specific genetic alterations. By contrast, treatment for nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) patients still remains limited to combination of radiotherapy and cytotoxic agents for example, cisplatin, 5-FU, palictaxel and gemcitabine4. To this end, several groups have also explored the potential of using anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies (cetuximab and nimotuzumab) with radiotherapy and chemotherapy in improving outcome of NPC patients but the results thus far, have been mixed5,6,7. It is worth mentioning that newly diagnosed NPC patients generally respond favorably to available first line treatment, but many face a risk of developing debilitating side effects such as mucositis that severely impacts the quality of life8, although these are reduced by improved precision of radiotherapy9. Even with the best treatment, up to 30% of cases end up with treatment failure, with distal control being the major challenge9.

Therefore, there is a pressing unmet need to expand the current treatment options, particularly for metastatic disease, preferably through biomarkers guided approach for NPC patients to improve clinical outcome and overall survival. This is especially important in Malaysia where this cancer remains the fifth most common10, often diagnosed at advanced stages III and IV11 and with the highest incidence rates amongst the local indigenous population compared to neighbouring countries12.

While deregulated expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes are now known to contribute to cancer, they do not always offer sufficient information for guiding treatment decisions. For example, lung cancer patients expressing high epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) levels may not all benefit from anti-EGFR therapies (i.e. erlotinib/gefitinib), while those harboring gain of function mutations which led to constitutive activation of this mitogenic pathway are likely to be responsive and confer prolonged median survival13,14. In this regard, EGFR-mutant advanced lung cancer patients are reported to have a higher 5-year survival (14.6%)13 with anti-EGFR therapies when compared to unselected patients (8.4%)14. However, the mutational status of a single gene alone can in some cases, fail to provide benefit with this class of targeted therapy. For instance, EGFR-mutant colorectal and lung cancer patients are essentially resistant to anti-EGFR therapies if accompanied by KRAS mutation15,16. Notwithstanding, the successful translation of mutation status in guiding oncology treatment decision has gained increasing attention and the growth in this field has been accelerated with the advent of next generation sequencing17,18.

It follows that with the current next generation sequencing capabilities, we are now able to exquisitely tease out the complex genetic information underlying cancer development and concurrently identify relevant gene signatures that are unique to each tumor and link these to drug response with the clear view of identifying new therapies as treatment options19,20,21. Exome sequencing is a cost-effective approach to identify mutational profile, and has been used extensively for discovering driver mutations as well as to uncover new potential treatment strategies for various cancer types. For instance, gallbladder carcinoma which has limited treatment options and poor survival, now may be amenable to tyrosine kinase inhibitors, in which genes involved in the ERBB pathway were found recurrently mutated (n = 21/57; 36.8%) by employing exome sequencing22. Given that genome wide sequencing data are meaningful to identify genomic similarities between different cancers that may be sensitive to the same treatment regimen, numerous high throughput cancer sequencing projects have been conducted, especially by The Cancer Genome Atlas network on various cancer types, including breast23, acute myeloid leukemia24, lung25, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas26 and many others. Indeed, several ongoing clinical trials for example, NCI Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (MATCH) and FOCUS4, now employ predetermined mutational profile of the cancer before giving the relevant targeted therapy27.

To date, limited information is available on key molecules and actionable targets that can be exploited for predicting drug sensitivity to existing therapeutics and/or developing new therapies for NPC. In this regard, earlier studies reported that hotspot mutations across 19 common oncogenes/tumor suppressor genes (e.g. TP53, KIT, KRAS) are infrequent in NPC tumors28, highlighting that genome wide screening remains pivotal for enhancing our current understanding on aberrant mutational events that likely drives NPC pathogenesis. Recently, Lin et al.29 has identified several potential targets for NPC based on genomic alterations using the exome sequencing approach, that may form the basis for exploring targeted therapies. Therefore, to make further inroads into identifying genetic changes underpinning NPC pathogenesis and consequently druggable targets, we performed whole exome sequencing on a small cohort (n = 10) of untreated freshly frozen and clinically annotated NPC tumor biopsies and from the emerging data, we screened 42 prioritized candidate genes in additional 88 NPC tumor biopsies collected from local hospitals, to determine their frequency of occurrence in multi-ethnic Malaysian NPC patients. Our data demonstrated that several genes in key cancer pathways (EGFR-PI3K-Akt-mTOR, NOTCH, NF-κB, DNA repair) were mutated, suggesting their potential use as predictive markers for targeted therapies to improve survival and outcome of NPC patients.

Results

Patient demographics

Clinicopathological details of the NPC patient samples are summarized in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1. From the 98 tumors that were included in the Discovery (n = 10) and Prevalence cohorts (n = 88), the majority were from patients of Chinese origin (70%), while the remaining ~30% were Malay, Indigenous and other sub-category. Notably, a higher ratio of males to females (3.7:1) was embedded in our sample demographics and consistent with the ~3-folds higher incidence of NPC in males than females30. The median age at diagnosis was 51 years, while a notable number (7%) were below 35 years of age upon diagnosis.

Table 1. Clinicopathological details of the NPC sample cohort used.

| Characteristics | Patients | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | ||

| Chinese | 69 | 70% |

| Malay | 5 | 5% |

| Indigenous | 15 | 15% |

| Others | 9 | 9% |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 77 | 79% |

| Female | 21 | 21% |

| Age at diagnosis | ||

| Median | 51 | |

| ≤35 | 7 | 7% |

| 36–40 | 8 | 8% |

| 41–50 | 31 | 32% |

| 51–60 | 34 | 35% |

| >60 | 17 | 17% |

| NA | 1 | 1% |

| WHO type | ||

| I | 1 | 1% |

| II | 16 | 16% |

| III | 81 | 83% |

| Clinical stage | ||

| I | 1 | 1% |

| II | 17 | 17% |

| III | 48 | 49% |

| IVA and IVB | 23 | 23% |

| IVC (metastasis) | 9 | 9% |

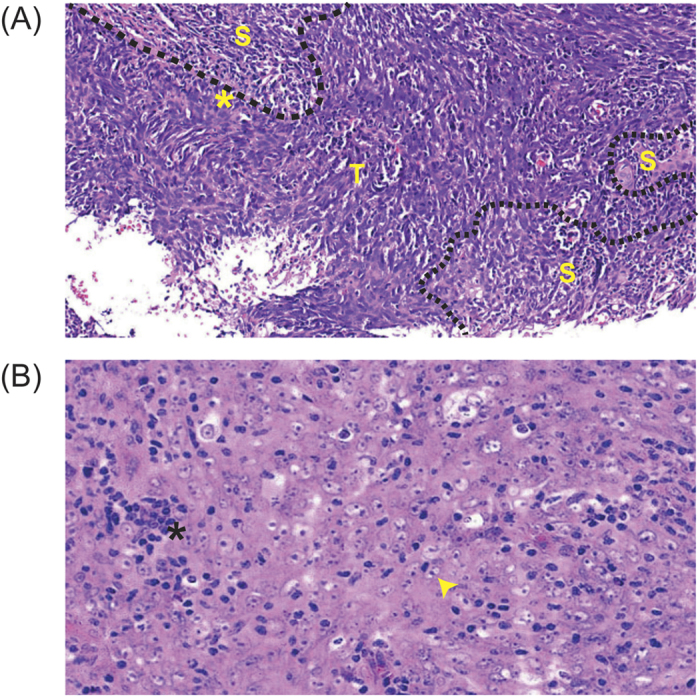

NPC is a malignancy of the epithelium that shows a variable degree of squamous differentiation where the vast majority of tumors, are undifferentiated without evidence of keratinization and are typically WHO types II and III. Furthermore, the association with Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) is consistent across all types of NPC although the viral presence may be difficult to demonstrate in those lesions that are WHO type I31. The majority of the samples in our study cohort were categorized as WHO Type III NPC (83%) and diagnosed at an advanced stages of the disease (III and IV), in accordance with earlier reports31,32. Detailed histopathological evaluation of all tissues revealed that the tumor content was approximately 40–100% and this is detailed together with the clinical TNM classification in Supplementary Table 1. Figure 1A shows a representative case of a Type II, undifferentiated and non-keratinizing carcinoma of the nasopharynx used in this study where the presence of elongated and spindle shaped tumor cells exhibiting dark nuclei are seen invading the stroma, forming syncytial sheets in intimate relationship with stromal infiltrates of lymphocytes. Figure 1B depicts an example of an undifferentiated Type III carcinoma of the nasopharynx used in this study where the tumor cells are observed to be oval and rounded, with eosinphilic cytoplasm and large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli. The growth pattern is largely syncytial and occasional small lymphocytes are observed intermingled with tumor cells. Of note, as a large proportion of patients failed to return for follow up, either after the initial diagnosis or treatment, the prognostic value of the candidate mutations could not be assessed.

Figure 1. Representative NPC cases used in this study.

(A) Undifferentiated and non-keratinizing carcinoma of nasopharynx (WHO Type II). The tumor cells are elongated and spindle shaped, exhibit dark nuclei and invade the stroma forming syncytial sheets (*). A stromal infiltrate of lymphocytes is apparent and the broken line represents boundary between stroma (S) and tumor (T) (20X). (B) Undifferentiated carcinoma of nasopharynx (WHO Type III). The tumor cells are oval and rounded, with large vesicular nuclei and prominent nucleoli (arrow head). The growth pattern is largely syncytial and occasional small lymphocytes (*) are observed intermingled with tumour cells (40X).

Identification of somatic mutation by whole exome sequencing

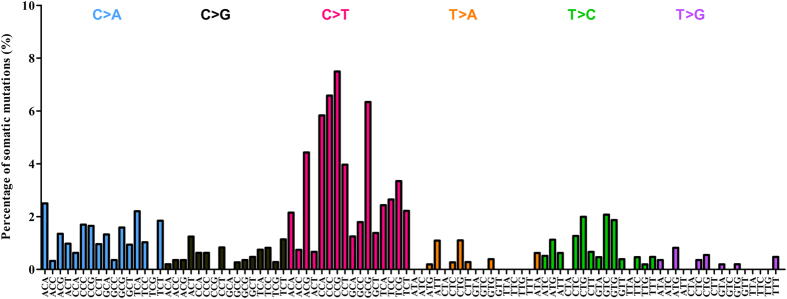

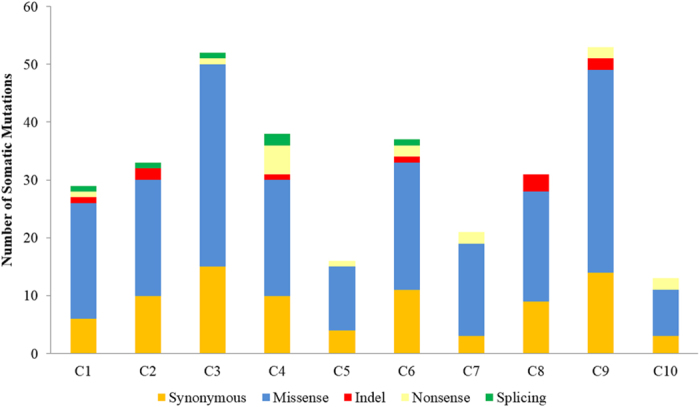

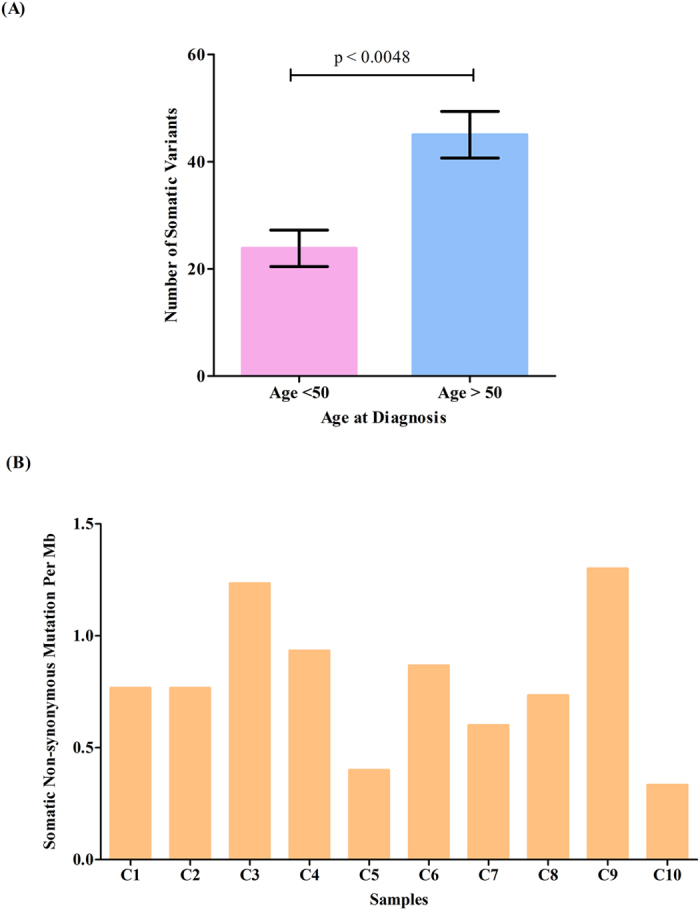

To explore the mutational landscape of NPC, we first performed whole exome sequencing on DNA extracted from 10 untreated NPC biopsies with at least 80% tumor content (Supplementary Table 1) and matched normal blood. The mean depth coverage was 110X for the tumors and 109X for matching normal (blood) (Supplementary Table 2). All samples had >96% of targeted bases represented by at least 10 reads (Supplementary Table 2). After filtering the exome data to exclude germline variants and reported polymorphisms, a total of 323 somatic mutations (206 missense, 85 synonymous, 16 nonsense, 6 splicing, 10 indel) affecting 308 genes were identified from the protein coding regions (Supplementary Table 3). A total of 30 candidate mutated genes fulfilling one of the following criteria: (1) cancer gene census; (2) mutations affecting functional domains; (3) predicted deleterious by SIFT or Polyphen2; (4) reported to be involved in tumorigenesis; were selected for validation by Sanger sequencing. Sequence validation revealed that 29/30 variants were confirmed true positive as somatic mutations (present in tumor and absent in matched normal DNA), yielding a true positive rate of ~97% (Supplementary Table 4). A mean of 32 somatic variants per patient (range 13–53 variants) were detected in our Discovery set, with the majority being identified as synonymous and missense (Fig. 2). Mutation spectra analysis with regards to the trinucleotide context showed that the C:G > T:A transitions was the most predominant (n = 164/313) in our Discovery set of 10 NPC tumors. Notably, ~50% of the trinucleotide alterations were occurring at CpG dinucleotides (Fig. 3), a signature that has now been reported to be associated with spontaneous DNA cytidine deaminase activity of APOBEC3B33,34, and consistent with observations recently reported29. When the age of the patients was factored into our data, those over 50 years of age had significantly more variants (range 37–53) as compared to those below aged 50 (range 13–33) (Fig. 4A) (p-value = 0.0048), which likely support the notion that mutational accumulation increases with age and can add value as a predictor of a poorer outcome35,36. Furthermore, we did not observe notable correlation between the number of somatic mutations and tumor stages (early stage II compared to late stages III & IV, p-value = 0.26). An average nonsynonymous somatic mutation rate of 0.79 per Mb (range 0.33–1.3) was found in our Discovery set (Fig. 4B). Although recurring mutation (same mutation in multiple samples) was not observed in our analysis of 10 NPC exomes, 6 genes were found to be commonly mutated in multiple samples, i.e. CXorf22 (p.H235Y, p.A940T), MYH1 (p.A338T, p.R109C), N4BP1 (p.G685E, p.R597X), WDR87 (p.D2021E, p.M1261I), TRAF3 (p.R163X, p.S9fs), and KCNN3 (p.P81delinsQQQQQP, p.L66H).

Figure 2. Distribution of somatic mutations identified from the Discovery set.

Whole exome sequencing of the samples (C1-C10), a total of 323 somatic variants affecting 308 genes were identified, of which 238 were non-synonymous (10 indel, 16 nonsense, 6 spicing, 206 missense), and 85 were synonymous.

Figure 3. Distribution of nucleotide changes of the somatic mutations identified from the Discovery set.

Mutations identified are shown in their trinucleotide context, which is defined by the substituted base flanked by immediate 5′ and 3′ bases. Analysis based on 96-substitution classification revealed that C to T transition is shown to be predominant in the NPC Discovery set as well as an enrichment in NpCpGp context, a signature which is associated with spontaneous deamination by APOBEC3B.

Figure 4. Association of somatic mutations with patients’ age and the mutation rate in NPC.

(A) NPC patients aged >50 years are shown to have a significantly higher number of variants as compared to those <50 years (p = 0.0048, unpaired T test). (B) A nonsynonymous somatic variant rate of 0.79 per Mb (range 0.33–1.3) was identified in the Discovery set.

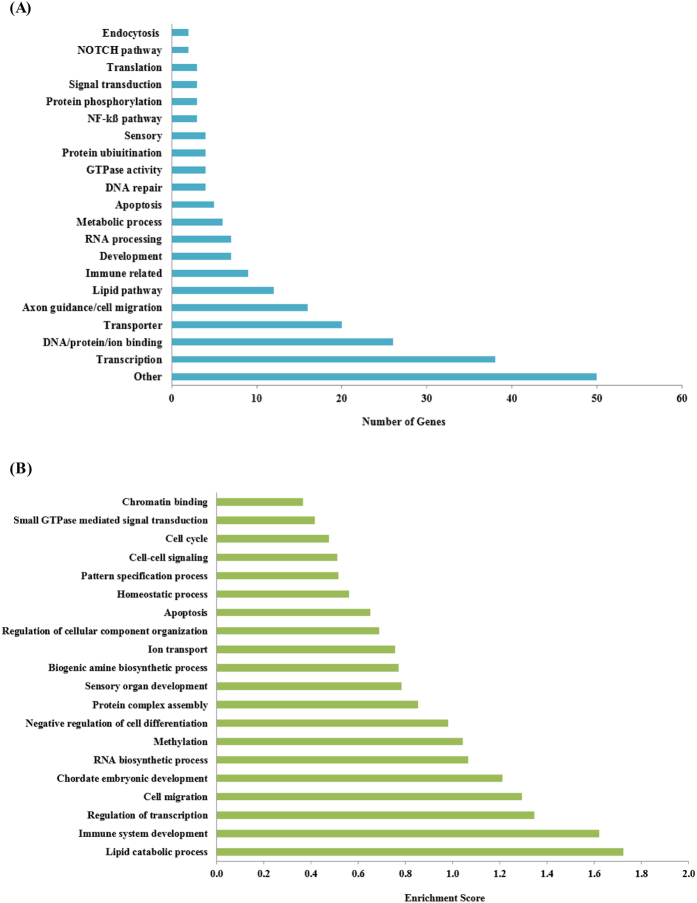

Enriched altered pathways in NPC

As depicted in Fig. 5A, classification of genes with protein-altering mutations using gene ontology biological process terms showed that transcription factors were the most significant enriched class of mutated genes (38/238 genes; 16%), in which all the samples analyzed (Discovery set only) harbored at least one mutated transcription factor. Among those, MED12, CDX2, MLL and MLL3 are cancer census genes, which are found frequently mutated in other cancers (COSMIC). For example, MLL3 ranked the six most commonly mutated gene in breast cancer23 (7%), but have not been reported for NPC. Other notable features included signaling pathways associated with the several of the mutated genes, for example, DNA repair (ATM, TP53, FEN1), NF-κβ pathway (TRAF3, NLRP6, CC2D1A), NOTCH (NOTCH2, DLL1, FBXW7) and lipid signaling (ASPG, CHKB, CPS1, IMPAD1, LPIN3, OXCT1, PHLDB2, PLCG1, PLCH1, PLCH2, PRKCZ, SYNJ1), many of which may have potential therapeutic implications.

Figure 5. Over-represented biological processes and pathways associated with mutated genes in NPC.

(A) Mutated genes giving rise to altered protein expression identified and those encoding transcription factors where the most commonly impacted in the Discovery set. (B) Functional clustering using DAVID revealed that lipid catabolic process was the most significantly enriched pathway identified from protein altering mutated genes in the Discovery set.

Based on DAVID functional clustering analysis, the genes with somatic variants in our study were most enriched in the lipid catabolic process (enrichment score = 1.72), followed by immune system development (enrichment score = 1.62) and regulation of transcription (enrichment score = 1.35) (Fig. 5B). Overall, our analysis revealed that 7/10 samples of the Discovery set harbored mutations implicated in lipid signaling, NOTCH, NF-κB pathway and DNA repair mechanisms. As these pathways are druggable and that the predictive value of these somatic mutations can potentially identify NPC patients likely to benefit from selected targeted therapy, further investigation is warranted.

Haloplex targeted resequencing

To identify frequently mutated genes implicated in NPC, a total of 37 candidate genes (those known to be implicated in cancer pathogenesis) and 5 mutated cancer genes listed in COSMIC (EGFR, CDKN2A, PTEN, KRAS, PIK3CA), were prioritized for further assessment with an additional 88 NPC cases. Targeted deep sequencing approach was carried out with a mean read depth of 2183X for the targeted regions and an average of 95.8% of the analyzable targeted bases being represented by at least 100 reads (Supplementary Table 6).

Overall, a total of 9987 variants were detected in our Prevalence set (Supplementary Table 7) and in order to evaluate the validity of recurring variants (same mutation occurring in multiple samples), 12 of the recurring variants from 25 NPC cases leading to 28 PCR reactions were randomly selected for evaluation by Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Table 8). Comparing recurring variants detected in 3 or less samples (≤3) to those detected in more than 3 samples (>3), we observed that the true positive rate differed from 100% to 24% (11/11 to 4/17, Supplementary Table 8). As a consequent of this observation, recurring variants detected in >3 samples were omitted from downstream analysis to eliminate false positive variants, which likely arises due to PCR artefacts. After removal of synonymous variants and known polymorphisms, except for those reported in the COSMIC database, our analysis detected a total of 160 putative non-synonymous variants affecting 37/42 genes in 66/88 NPC patients (Supplementary Table 9).

Of these 160 non-synonymous variants, those in the top five most frequently mutated genes, namely TP53, NOTCH2, PLXNB3, ATM, and PPP1R15A, all recurring variants, and together with some randomly selected variants were prioritized for validation by Sanger sequencing. Samples with no remaining DNA or PCR products failing to be amplified were omitted from validation by Sanger sequencing. Sanger sequencing validated variants with unavailable germline DNA to determine somatic origin were denoted as somatic/germline. Overall, Sanger sequencing results confirmed 78% (77/99) putative non-synonymous variants identified by haloplex as true positives (Supplementary Table 9).

For the selected top five most frequently mutated genes detected in our prevalence set, TP53 was confirmed with 9 somatic and 1 somatic/germline variants. NOTCH2 was confirmed with 2 somatic, 7 germline and 1 somatic/germline variants. For PLXNB3 variants, 3 were somatic, 1 was germline and 1 was somatic/germline. ATM was confirmed with 7 germline variants while PPP1R15A confirmed with 1 germline variant (Supplementary Table 9). Among the 24 recurring variants, only 16 candidates were validated by Sanger sequencing in all samples harbouring the putative variants. Sanger sequencing confirmed 2/16 were recurring somatic variants, 6/16 were recurring germline derivatives, 2/16 with mixed profile, and remaining 6 were noted as false (Supplementary Table 9).

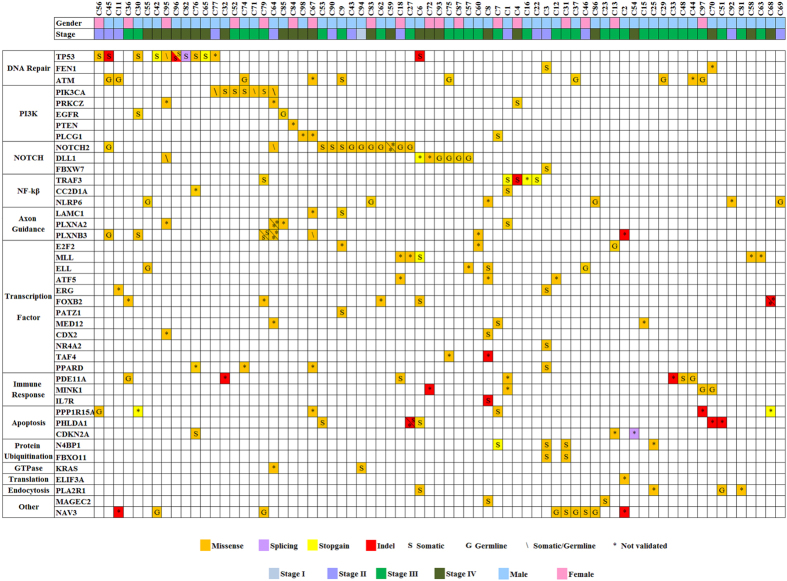

In summary, our findings fall broadly in concordance with those of Lin et al.29 reporting that NPC genomic landscape harbors a very limited number of somatic variants as compared to other types of human cancers. Nonetheless, from our combined Discovery and Prevalence sets, 72% (71/98) of NPC cases had frequently mutated genes involved in cancer pathways (Fig. 6). The most affected pathways include the DNA repair (i.e. TP53, ATM, FEN1, n = 22/98, ~22%), NOTCH (i.e. NOTCH2, DLL1, FBXW7, n = 20/98, ~20%), EGFR/PI3K/Akt/mTOR (i.e. PIK3CA, PRKCZ, EGFR, PTEN, PLCG1, n = 15/98, ~15%) and the NF-κB pathway (i.e. TRAF3, CC2D1A, NLRP6, n = 12/98, ~12%) (Fig. 6). Variants found in these pathways, irrespective of germline or somatic, may potentially serve as predictive biomarkers for targeted cancer therapies. Of interest, although we found no significant differences in the number of non-synonymous variants among different disease stage (data not shown), we did note that 44% (4/9) of Stage 4 C metastatic NPC cases had mutations in the DNA damage response compared to 20% (18/89) in non-metastatic cases (Supplementary Figure 1). Taken together, our findings revealed that a subset of NPC patients may be amenable to biomarker-guided therapies targeting EGFR-PI3K-Akt-mTOR, NOTCH, NF-κB signaling and DNA repair pathways.

Figure 6. Mutational landscape of candidate genes detected in the NPC tumor cohort.

Each column represents an individual affected case, and each row denotes a specific gene assigned to one of the labeled functional categories (left panel). Each type of mutation class is indicated by color, symbol G indicated validated germline variant, symbol S indicated validated somatic variant, symbol \ indicated somatic/germline variant, and symbol * indicated non-validated variant. Patients’ gender and clinical staging are shown in the top panel.

Discussion

It is well accepted that cancer arises from somatically acquired mutations and the identity of these affected molecules can lead to developing actionable targeted therapies. Indeed, several somatic mutations have now been developed into molecular screening tools (companion tests) for guiding precision therapies13,14,37,38. For example, the current practice of matching non-small cell lung cancer patients carrying EGFR mutations to afatinib/osimertinib/erlotinib small molecule class of therapies, whereas those with wildtype alleles to be administered with conventional chemotherapies13,14,38. This also includes matching those lung cancer patients who may have acquired the EGFR T790M mutation conferring resistance while on prior therapy with EGFR small molecule inhibitors and prescribing new generation of targeted therapies to help override this. For example, AZD9291, a selective oral EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor was found to be active in patients with EGFR T790M mutation39. Furthermore, the presence of the BRAF V600 variant in melanoma patients predicts benefit with FDA approved small molecule therapies, and vermurafenib has been shown to give benefit to BRAF V600E positive metastatic melanoma patients37,40. Unlike other solid tumors that have well characterized genomic profiles via next generation sequencing (e.g. breast and lung cancer)23,25, little is known about the genetic landscape underpinning NPC pathogenesis. This likely reflects the fact that to date, limited options for targeted therapies for NPC and consequently, there is considerable interest in identifying variants that can be predictive of treatment response, allowing NPC patients to be better matched with anti-cancer therapies based on the tumor genotype. In this study, genes which are involved in several druggable pathways, namely the EGFR-PI3K-Akt-mTOR, NOTCH, NF-κB signaling and DNA repair pathways were found to be commonly mutated in a large multi-ethnic Malaysian NPC samples cohort (n = 98).

Defects in DNA repair mechanism represents key events in tumorigenesis, and is most commonly observed in our samples set (n = 22/98) especially in metastatic NPC (n = 4/9). TP53, referred to as the guardian of the genome, essentially functions as a tumor suppressor by maintaining genome stability and integrity through cell cycle checkpoints41. While loss of function mutations for this gene are the most frequently reported for human cancers (COSMIC; http://www.cancer.sanger.ac.uk), for NPC, several studies have reported a lower frequency, broadly in the range of ~10% using both the Sanger42,43,44,45,46 and exome sequencing approaches29. In concordance with these earlier studies, we noted that in our study TP53 was mutated at a frequency of ~11% (n = 11/98). Despite a lower prevalence of TP53 mutations in our NPC samples as compared to other tumor types, loss of function in TP53 nonetheless represents a key genetic defect underpinning NPC pathogenesis. In total, we detected 12 mutations in 11 patients, which include 5 truncating mutations (p. R342fs, p.R213X, p.R306X, p.L330fs, p.S95fs), 1 splicing mutation (c.375 + 1 G > C), and 6 missense mutations (p.R248Q, p.R282W, p.G245D, p.Y126H, p.V31I, p.R273C). Of note, the TP53 variant p.S95fs, was initially detected as p.S95Y in our Haloplex analysis, however validation by Sanger sequencing identified this as a frameshift mutation, suggesting confirmation with this second method should be incorporated into clinical diagnosis for guiding treatment decision. Interestingly, TP53 has been reported to be involved in metastasis by inducing cell invasion and migration processes47, and TP53 deficient tumors are associated with a poorer outcome48,49,50,51. The prognostic value of TP53 mutations in NPC is yet to be determined and likely an area of investigation that has value. From a treatment perspective, nutlin-3a, a small-molecule that inhibits TP53-MDM2 interaction, can reactivate TP53 function52, thereby inducing cell cycle arrest and apoptosis53. Given that nearly 90% of NPC harbour wildtype TP53, nutlin-3a has potential as a therapeutic agent for NPC patients54. Preclinical studies have shown that nutlin-3a is broadly effective against cancer cells expressing TP53 either as a single agent55,56, or in combination with chemotherapeutic agent, such as cisplatin in NPC, lung and ovarian cancer54,55,57. In addition to somatic TP53 mutations, our data revealed non-synonymous mutations in ATM, another DNA repair gene in a subset of NPC (n = 10/98, ~10%). Although the pathogenic roles of these mutations currently remain unknown, PARP inhibitors have recently been reported to give benefit to patients harboring germline defects in key DNA repairs genes, including BRCA, ATM, CHEK2 and TP5358,59,60,61,62. Given that olaparib has recently been approved for the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer with deleterious BRCA mutations58,63, this may serve as a therapeutic window with FDA approved therapies for NPC patients with similar gene defects. The presence of mutations of the DNA damage pathway in NPC raises the possibility of using drugs targeting the pathway which could lead to synthetic lethality64, particularly for metastatic NPC where treatment options are limited.

From our analysis, we noted that NOTCH2 was the most frequently mutated gene (n = 12/98; 12%). Also, a total of 20/98 samples (~20%) harbored mutation in genes associated with the NOTCH pathway (FBXW7: n = 1; NOTCH2: n = 12, DLL1: n = 7). This indicates that this pathway is the second most frequently mutated, and serve as promising treatment approach for NPC patients. While the association of NOTCH signaling and NPC pathogenesis remains unclear, our findings is the first to report FBXW7 and DLL1 mutations in this cancer type. Notwithstanding, FBXW7 is a key component of the NOTCH pathway and functions by mediating ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of several oncoproteins, including cyclin E, Notch, Jun and c-myc by forming ubiquitin ligase complex65,66. As loss of function mutations in FBXW7 have been reported in several malignancies to be associated with resistance to various drugs for example, γ-secretase inhibitor MRK-003 in T-ALL67, palictaxel in breast cancer68 and trastuzumab in gastric cancer69, suggesting that the utility of FBXW7 (p.S558F) to predict drug sensitivity in NPC warrants further investigation. While DLL1 functions as one of several ligands for NOTCH receptors, the pathogenic impact of mutations detected in our NPC samples remains unexplored. Given that NOTCH2, FBXW7 and DLL1 are key components in NOTCH signaling and have predictive value in cancer therapies, the effect of these mutations in NPC is yet to be elucidated.

Our mutational analysis also showed a trend towards an enrichment in the EGFR/PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway where mutations in PIK3CA (n = 7), PLCG1 (n = 3), EGFR (n = 2), PTEN (n = 1), and PRKCZ (n = 3) were identified in ~15% of our sample cohort. While PIK3CA mutations have now been reported to be present in 25–30% of human cancers including colorectal, gastric, oral squamous and brain70,71,72, this frequency is at a lower rate for NPC (5–9%)29,73,74, despite reported being amplified and overexpressed in ~70% of lesions analyzed75. We did not detect PIK3CA mutation in our discovery set, however 2 commonly found activating mutations in hotspot exon 9 (p.E542K: n = 2; p.E545K: n = 3) were noted in our validation cohort. To this end, gain of function mutations in PIK3CA can result in constitutive activation of the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signaling axis, which then promotes key hallmarks of oncogenesis, including proliferation, metastasis, angiogenesis and chemoresistance76,77,78. It follows that the presence of PIK3CA mutations is being exploited as a predictive marker of benefit as indicated in a recent clinical trial of PI3K/Akt/mTOR inhibitors on patients with advanced cancers, where a higher response rate was observed in patients with the mutation as compared to those without79,80,81. Also, everolimus for targeting tumors with PIK3CA mutations is currently under clinical evaluation (https://clinicaltrials.gov/). Taken together, the presence of PIK3CA mutations in our samples cohort suggests that a substantial number of NPC patients can likely benefit from therapies that target the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Beyond that, other mutations which fall into the EGFR-PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway may also have therapeutic values. We detected 2 novel mutations in EGFR (p.L49F, p.K253R) and may provide the basis for testing current FDA approved anti-EGFR therapies. Also, both PRKCZ and PLCG1 are intracellular receptor mediators for EGFR, PI3K, and VEGFR tyrosine activators82,83,84, which are involved in carcinogenesis by promoting cell growth, invasion and migration85,86,87. Hence, mutations detected in PLCG1 (p.R187W, p.I1092V, p.R1229W) and PRKCZ (p.V283L, p.F517V, p.T99P), (encoding phospholipase Cγ1 and protein kinase C ζ, respectively), may hold value as predictive markers for anti-PI3K/Akt/mTOR therapies.

NF-κB represents an important transcription factor involved in the regulation of proliferation, apoptosis, metastasis and angiogenesis88,89. TRAF3 is among the player negatively regulating canonical and non-canonical NF-κB activity and in mediating immune response by interacting with TNFR superfamily90. With regards to NPC, TRAF3 truncating mutations have been reported in NPC C666 cells (c.415delA), as well as in 1/33 primary NPC tumors (p.N139MfsX20) suggesting a causal role in disease pathogenesis91. In addition, other NF-κB pathway associated genes, i.e. A20 and TRAF2 were also found mutated91. Beyond that, inactivation of TRAF3 function may mediate NPC tumor cells survival upon Epstein-Barr virus infection by suppressing the production of interferon immune responses91. In this study, we detected 5 non-synonymous variants in TRAF3 that included 3 nonsense (p.Q114X, p.R163X, p.R505X), 1 frameshift deletion (p.S9fs) and 1 missense (p.G480E) in 5/98 samples (~5%). On closer assessment of the sequence harboring these defects, we noted that the nonsense and deletion would have resulted in the loss of the TRAF3 domain, essential for negatively regulating NF-κβ may lead to increased activity of the pathway92,93,94,95. Several studies have now demonstrated that targeting the NF-κB pathway is a promising treatment strategy for a variety of cancers such as breast96, colorectal97, and head and neck98. Most notably, bortezomib, which inhibits NF-κB activity by blocking IκB degradation99, has been approved for the treatment of multiple myeloma100,101. Over-expression of NF-κB has been reported to be associated with poorer prognosis in NPC102,103 and therefore supporting the rational of exploiting NF-κB inhibitor as potential treatment strategy for NPC. Previous study has reported NF-κB inhibitors DHMEQ and BAY 11-7082, by blocking the nuclear translocation of activated NF-κB were effective in inhibiting NPC HK1 cell growth, induced apoptosis and abrogated their invasiveness and anchorage independent growth104. Furthermore, recent study by Peng et al.105 also showed that andrographolide inhibited proliferation and invasiveness of NPC HK1 cells via suppressing NF-κB transcriptional activity, thus providing a rational for the possibility of utilizing the NF-κB activation status to stratify NPC patients who may be more likely to benefit therapy with NF-κB inhibitors. From our observations, there is the possibility of incorporating TRAF3 loss of function mutations as predictive biomarker of response to NF-κB inhibitors, and warrants further investigation.

Overall, alterations impacting EGFR-PI3K-Akt-mTOR, NOTCH, NF-κB signaling and DNA repair pathways accounted for ~72% (n = 71/98) of the NPC samples analyzed, and may be useful to predict clinical benefit in NPC patients. Among the potential matched drug-gene candidates including NF-κB inhibitors (TRAF3), NOTCH inhibitors (NOTCH2, FBXW7), nutlin-3a (TP53), PARP inhibitors (TP53, ATM), AKT-PI3K-mTOR inhibitors (PIK3CA, PRKCZ, PLCG1), and EGFR inhibitors (EGFR). Further investigation is warranted to validate these targets and to provide a more defined framework for clinical evaluation in NPC patients who may likely have exhausted the available standard of care therapies as well as newly diagnosed NPC patients. However, it is worth mentioning that validation of some of the observed mutations using cellular based or mouse xenograft models currently represents a major challenge as many of the available NPC cell lines are now reported to be contaminated with HeLa cells106,107.

Materials and Methods

Patient samples

This study was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations by the ethics committee as indicated. Fresh frozen primary biopsies and matched normal blood samples from newly diagnosed and untreated NPC patients were collected from Tung Shin Hospital (TSH; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), Kuala Lumpur Hospital (KLH; Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia), Penang Hospital (PH; Penang, Malaysia), Queen Elizabeth Sabah Hospital (QESH; Sabah, Malaysia), and Sarawak General Hospital (SGH; Sarawak, Malaysia). Samples from TSH were obtained with approval from the ethics committee and signed informed consent from patients. Samples from KLH, PH, QESH and SGH were obtained with approval from the Medical Research and Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-12-1203-14027) and signed informed consent from each patient.

Sample preparation

For this study, a total of 10 cases were included in the initial Discovery set and 88 for the Prevalence set. Each sample after embedding in OCT were, cryosectioned using a cryostat (Leica Biosystems, IL, USA). For each sample, a 5 μm cryosection reference slide was made prior and after the collection of ~20 cryosections (each ~25 μm) in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes. All reference slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) followed by histopathological evaluation by pathologists (RP and NKMK) to confirm the pathogenesis of the lesions including the levels of tumor cells presents following the classification described by Shanmugaratnam & Sobin (1978)108.Only those cryosections collected where the tumor content was confirmed to be ~40–70% were processed for DNA extraction. Clinicopathological information of our patient cohort is summarized in Table 1 and additional details are given in Supplementary Table 1.

Genomic DNA extraction

Blood DNA matching to the patient cohort was extracted using QIAampBlood Mini Kit (Qiagen, CA, USA) while tumor cryosections collected in microcentrifuge tubes were extracted using the QIAamp AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini (samples from TSH) or QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (samples from KLH, PH, SGH, QESH) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The extracted DNA samples from both blood and tumor tissues were quantified using the PicoGreen dsDNA Quantitation Reagent (samples from TSH) or the Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay Kit (samples from KLH, PH, SGH, and QESH).

Whole exome sequencing

Whole exome sequencing was carried out using tumor and blood DNAs of the Discovery set. Firstly, ~3 μg of DNA was sheared using Covaris focused-ultrasonication (Covaris, MA, USA), followed by end repaired and ligation with paired-end adaptor. The adaptor-ligated libraries were then hybridized with SureSelect Human All Exon 51 Mb probes, followed by exome capture using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). The captured exomes were then pooled and sequenced using the Illumina Hiseq 2000 platform to generate 91–101 bp paired-end reads to an average coverage of ~100X. The library construction and sequencing were performed by Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI, Shenzhen, China), following their in-house protocols.

Identification of somatic mutations from exome data

Fastq files of the whole exome sequencing were obtained from BGI for further analysis. Sequencing reads from tumor and matched normal blood DNAs were separately aligned to the human reference genome hg19 using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner109. Local realignment was performed using Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK)110, followed by PCR duplicates removal using Picard tool (http://picard.sourceforge.net). Next, variants from both normal and tumor samples were identified using GATK pipeline. Briefly, base qualities were recalibrated, and the GATK UnifiedGenotyper was subsequently employed to call SNVs and Indels. Only well-mapped reads (mapping quality of ≥30 and number of mismatches ≤3 within a 40-bp window) were used as input for the UnifiedGenotyper. Variants that passed additional quality filters (quality by depth of ≥1.5, variant depth of ≥2, total depth ≥10) were retained. To identify somatic mutations (single nucleotide variants [SNVs] and short insertions and deletions [Indels]), variants identified from tumor and matched blood DNA samples were initially compared with dbSNP137, 1000 Genomes Project, Complete Genomic Project (cg69), and National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI; NIH, USA) databases to eliminate any previously reported polymorphisms. Somatic mutations were then identified essentially by subtracting variants in normal DNA samples from the tumor samples and subjected to annotation using ANNOVAR111 based on NCBI Refseq database. Only somatic mutations in exons or in splice sites were further analyzed. All potential somatic mutations identified were manually inspected by using the Integrative Genomics Viewer112. Amino acid changes were annotated to the longest transcript of the gene, and the impact of somatic SNVs on protein function was predicted using SIFT113 and PolyPhen2114 (Supplementary Table 3). The putative non-synonymous mutations were analyzed for enriched functional groupings (Gene Ontology classification) using the Database for Annotation Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID)115. The list of genes identified as harboring SNVs and Indels were further analyzed and a subset was subsequently selected for external validation using targeted sequencing of the DNA samples from the Prevalence set (described below).

Haloplex Targeted Sequencing

For targeted sequencing of samples from the Prevalence set comprising of 88 NPC tumors and matched DNAs, a customized Haloplex Target Enrichment Panel (Agilent Technologies) was designed using Agilent SureDesign (https://earray.chem.agilent.com/suredesign). This customized panel covered 99.72% of the targeted region by a total of 19804 amplicons (Total Sequence-able Design Size: 400.037 kbp) and used to capture all exons of the selected 42 candidate genes of interest (37 genes prioritized from exome data and an additional top 5 mutated cancer genes). Briefly, each DNA sample was subjected to eight restriction digest reactions, hybridized with probes against target regions of the selected genes and underwent PCR amplification with Herculase II Fusion Enzyme (Agilent Technologies) to incorporate Illumina paired-end sequencing motifs and index sequences, followed by purification using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA). Each captured library were the pooled and subjected to 101-bp paired-end sequencing using the Illumina Hiseq 2000 platform by BGI. Variants from the resulting data were called using the SureCall pipeline (Agilent Technologies). The called variants were then annotated using ANNOVAR111 based on NCBI RefSeq database. To identify putative novel variants implicated in NPC pathogenesis, all the polymorphisms reported in dbSNP137, 1000 Genomes Project, Complete Genomic Project (cg69), and NHLBI databases were eliminated. Those coding variants reported in COSMIC database were retained. Only variants that affected the exonic and splicing regions were further analyzed.

Validation of mutations by Sanger sequencing

From our Discovery set a total of 30 candidate mutations, were selected for validation by Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Table 4). For the Prevalence set, recurrent variants and top 5 most frequently mutated genes were selected for Sanger validation. Somatic or germline status was also determined by Sanger sequencing, where matched blood DNA was available (Supplementary Table 9). Primers specific to the regions of interest harboring the mutations were designed using Primer 3 software (http://www.bioinformatics.nl/primer3plus) and these sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 5. Due to sample limitation, DNA samples from TSH were whole genome amplified using Repli-G Mini kit (Qiagen, GmbH, Germany) prior to use for further PCR amplification for Sanger sequencing. PCR amplification was conducted using Platinum Supermix (Invitrogen, CA, USA) for samples from TSH, or GoTaq Green Master Mix (Promega, Madison USA) for samples from KLH, PH, SGH and QESH. PCR cycling parameters included one cycle at 95 °C for 5 min, 40 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 55 °C to 60 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, and one cycle at 72 °C for 10 min. Sequencing was performed with ABI BigDye Terminator v3.1 (Life Technologies, CA, USA). The sequence chromatograms were visually inspected with Mutation Surveyor v4.0.4 (Softgenetics, State College, USA), Chromas Lite 2.1.1 or Bioedit software.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chow, Y. P. et al. Exome Sequencing Identifies Potentially Druggable Mutations in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 7, 42980; doi: 10.1038/srep42980 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This project received funding from the Ministry of Health, Malaysia (NMRR-12-1203-14027), Terry Fox Run KL Fund and Cancer Research Malaysia, a non-profit research organization. We thank the Director-General of Health, Malaysia for giving Institute of Medical Research, Malaysia permission to carry out this work and the Director of the Institute for Medical Research for continued support. We are also extremely grateful to the staff of Biospecimen bank and Molecular Pathology Unit as well as the Malaysian Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Study Group for their support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Y.P.C. and L.P.T. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript; S.J.C. and N.A.A. performed the validation experiments; S.W.C. assisted with interpretation of the data; P.V.H.L., C.L.L., K.C.P., Y.Y.Y. and T.Y.T. collected the NPC samples and the associated clinical data; R.P. and N.K.M.K. performed histo-pathological evaluation of tissue specimens; S.H.T., A.S.B.K. and V.P. conceived, supervised the research project and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

References

- Hensing T., Chawla A., Batra R. & Salgia R. A personalized treatment for lung cancer: molecular pathways, targeted therapies, and genomic characterization. Adv Exp Med Biol 799, 85–117, doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-8778-4_5 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tessari A., Palmieri D. & Di Cosimo S. Overview of diagnostic/targeted treatment combinations in personalized medicine for breast cancer patients. Pharmgenomics Pers Med 7, 1–19, doi: 10.2147/PGPM.S53304 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri A. et al. Individualized therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. J Intern Med 274, 1–24, doi: 10.1111/joim.12070 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bensouda Y. et al. Treatment for metastatic nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis 128, 79–85, doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2010.10.003 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibault J. E. et al. Toxicity and efficacy of cetuximab associated with several modalities of IMRT for locally advanced head and neck cancer. Cancer Radiother 20, 357–361, doi: 10.1016/j.canrad.2016.05.009 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai R. P. et al. Experience with combination of nimotuzumab and intensity-modulated radiotherapy in patients with locoregionally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 8, 3383–3390, doi: 10.2147/OTT.S93238 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. L. & Ma B. B. Novel systemic therapeutic for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Expert Opin Ther Targets 16 Suppl 1, S63–68, doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.635646 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovell S. J., Wong H. B., Loh K. S., Ngo R. Y. & Wilson J. A. Impact of dysphagia on quality-of-life in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck 27, 864–872, doi: 10.1002/hed.20250 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A. W., Ma B. B., Ng W. T. & Chan A. T. Management of Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma: Current Practice and Future Perspective. J Clin Oncol 33, 3356–3364, doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.60.9347 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizah Ab. M., Norsaleha I. T., Noor Hashimah A., Asmah Z. A. & Mastulu W. Malaysian National Cancer Registry Report 2007–2011, National Cancer Institute, Ministry of Health https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B59-Ld_mHScqTkhBaVNzOHNuQ0U/view (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Pua K. C. et al. Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma Database. Med J Malaysia 63 Suppl C, 59–62 (2008). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devi B. C., Pisani P., Tang T. S. & Parkin D. M. High incidence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma in native people of Sarawak, Borneo Island. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13, 482–486 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J. J. et al. Five-Year Survival in EGFR-Mutant Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma Treated with EGFR-TKIs. J Thorac Oncol 11, 556–565, doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.12.103 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino K. et al. A retrospective analysis of 335 Japanese lung cancer patients who responded to initial gefitinib treatment. Lung Cancer 82, 299–304, doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.08.009 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao C. et al. KRAS mutations and resistance to EGFR-TKIs treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a meta-analysis of 22 studies. Lung Cancer 69, 272–278, doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.11.020 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui A. D. & Piperdi B. KRAS mutation in colon cancer: a marker of resistance to EGFR-I therapy. Ann Surg Oncol 17, 1168–1176, doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0811-z (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou T., Kanai M., Matsumoto S., Okuno Y. & Muto M. The possibility of clinical sequencing in the management of cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol 46, 399–406, doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyw018 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman A. A., Letai A., Fisher D. E. & Flaherty K. T. Precision medicine for cancer with next-generation functional diagnostics. Nat Rev Cancer 15, 747–756, doi: 10.1038/nrc4015 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roychowdhury S. & Chinnaiyan A. M. Translating cancer genomes and transcriptomes for precision oncology. CA Cancer J Clin 66, 75–88, doi: 10.3322/caac.21329 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuckmann J. M. & Thomas R. K. A new generation of cancer genome diagnostics for routine clinical use: overcoming the roadblocks to personalized cancer medicine. Ann Oncol 26, 1830–1837, doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv184 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeron-Medina J., Ochoa de Olza M., Braña I. & Rodon J. The Personalization of Therapy: Molecular Profiling Technologies and Their Application. Semin Oncol 42, 775–787, doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2015.09.026 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M. et al. Whole-exome and targeted gene sequencing of gallbladder carcinoma identifies recurrent mutations in the ErbB pathway. Nat Genet 46, 872–876, doi: 10.1038/ng.3030 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network C. G. A. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490, 61–70, doi: 10.1038/nature11412 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network C. G. A. R. Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 368, 2059–2074, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1301689 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network C. G. A. R. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature 511, 543–550, doi: 10.1038/nature13385 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Network C. G. A. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature 517, 576–582, doi: 10.1038/nature14129 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfro L. A., An M. W. & Mandrekar S. J. Precision oncology: A new era of cancer clinical trials. Cancer Lett, doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.015 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N. et al. Hotspot mutations in common oncogenes are infrequent in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncol Rep 32, 1661–1669, doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3376 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D. C. et al. The genomic landscape of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Nat Genet 46, 866–871, doi: 10.1038/ng.3006 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson L. D. Update on nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol 1, 81–86, doi: 10.1007/s12105-007-0012-7 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathmanathan R. et al. Undifferentiated, nonkeratinizing, and squamous cell carcinoma of the nasopharynx. Variants of Epstein-Barr virus-infected neoplasia. Am J Pathol 146, 1355–1367 (1995). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei K. R., Xu Y., Liu J., Zhang W. J. & Liang Z. H. Histopathological classification of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 12, 1141–1147 (2011). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandrov L. B. et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500, 415–421, doi: 10.1038/nature12477 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns M. B., Temiz N. A. & Harris R. S. Evidence for APOBEC3B mutagenesis in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet 45, 977–983, doi: 10.1038/ng.2701 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie J. D. et al. Old age at diagnosis increases risk of tumor progression in nasopharyngeal cancer. Oncotarget, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10818 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedelnikova O. A. et al. Senescing human cells and ageing mice accumulate DNA lesions with unrepairable double-strand breaks. Nat Cell Biol 6, 168–170, doi: 10.1038/ncb1095 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guadarrama-Orozco J. A. et al. Braf V600E mutation in melanoma: translational current scenario. Clin Transl Oncol 18, 863–871, doi: 10.1007/s12094-015-1469-6 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. C. et al. Afatinib versus cisplatin-based chemotherapy for EGFR mutation-positive lung adenocarcinoma (LUX-Lung 3 and LUX-Lung 6): analysis of overall survival data from two randomised, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol 16, 141–151, doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71173-8 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jänne P. A. et al. AZD9291 in EGFR inhibitor-resistant non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 372, 1689–1699, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411817 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman P. B. et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med 364, 2507–2516, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103782 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane D. P. Cancer. p53, guardian of the genome. Nature 358, 15–16, doi: 10.1038/358015a0 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrani F. et al. Mutations clustered in exon 5 of the p53 gene in primary nasopharyngeal carcinomas from southeastern Asia. Int J Cancer 61, 316–320 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effert P. et al. Alterations of the p53 gene in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Virol 66, 3768–3775 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo K. W. et al. p53 mutation in human nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Anticancer Res 12, 1957–1963 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spruck C. H. et al. Absence of p53 gene mutations in primary nasopharyngeal carcinomas. Cancer Res 52, 4787–4790 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y. et al. An infrequent point mutation of the p53 gene in human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89, 6516–6520 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell E., Piwnica-Worms D. & Piwnica-Worms H. Contribution of p53 to metastasis. Cancer Discov 4, 405–414, doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0136 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira A. L. et al. Massively parallel sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in TP53 in thymic carcinoma associated with poor prognosis. J Thorac Oncol 10, 373–380, doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000397 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan P., Ji Y. N. & Yu L. K. TP53 mutation is associated with a poor outcome for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: evidence from a meta-analysis. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr 2, 260–265, doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2304-3881.2013.07.06 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Cuesta L. et al. Prognostic and predictive value of TP53 mutations in node-positive breast cancer patients treated with anthracycline- or anthracycline/taxane-based adjuvant therapy: results from the BIG 02-98 phase III trial. Breast Cancer Res 14, R70, doi: 10.1186/bcr3179 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overgaard J., Yilmaz M., Guldberg P., Hansen L. L. & Alsner J. TP53 mutation is an independent prognostic marker for poor outcome in both node-negative and node-positive breast cancer. Acta Oncol 39, 327–333 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shangary S. & Wang S. Small-molecule inhibitors of the MDM2-p53 protein-protein interaction to reactivate p53 function: a novel approach for cancer therapy. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 49, 223–241, doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.48.113006.094723 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassilev L. T. et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science 303, 844–848, doi: 10.1126/science.1092472 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voon Y. L. et al. Nutlin-3 sensitizes nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells to cisplatin-induced cytotoxicity. Oncol Rep 34, 1692–1700, doi: 10.3892/or.2015.4177 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanjirband M., Edmondson R. J. & Lunec J. Pre-clinical efficacy and synergistic potential of the MDM2-p53 antagonists, Nutlin-3 and RG7388, as single agents and in combined treatment with cisplatin in ovarian cancer. Oncotarget, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9499 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane E. K. et al. Nutlin-3a: A Potential Therapeutic Opportunity for TP53 Wild-Type Ovarian Carcinomas. PLoS One 10, e0135101, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135101 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deben C., Deschoolmeester V., Lardon F., Rolfo C. & Pauwels P. TP53 and MDM2 genetic alterations in non-small cell lung cancer: Evaluating their prognostic and predictive value. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 99, 63–73, doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.11.019 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim G. et al. FDA Approval Summary: Olaparib Monotherapy in Patients with Deleterious Germline BRCA-Mutated Advanced Ovarian Cancer Treated with Three or More Lines of Chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 21, 4257–4261, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0887 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mateo J. et al. DNA-Repair Defects and Olaparib in Metastatic Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med 373, 1697–1708, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506859 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota E. et al. Low ATM protein expression and depletion of p53 correlates with olaparib sensitivity in gastric cancer cell lines. Cell Cycle 13, 2129–2137, doi: 10.4161/cc.29212 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilardini Montani M. S. et al. ATM-depletion in breast cancer cells confers sensitivity to PARP inhibition. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 32, 95, doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-32-95 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson C. T. et al. Enhanced cytotoxicity of PARP inhibition in mantle cell lymphoma harbouring mutations in both ATM and p53. EMBO Mol Med 4, 515–527, doi: 10.1002/emmm.201200229 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledermann J. et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med 366, 1382–1392, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105535 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor M. J. Targeting the DNA Damage Response in Cancer. Mol Cell 60, 547–560, doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.10.040 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y. & Li G. Role of the ubiquitin ligase Fbw7 in cancer progression. Cancer Metastasis Rev 31, 75–87, doi: 10.1007/s10555-011-9330-z (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welcker M. & Clurman B. E. FBW7 ubiquitin ligase: a tumour suppressor at the crossroads of cell division, growth and differentiation. Nat Rev Cancer 8, 83–93, doi: 10.1038/nrc2290 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil J. et al. FBW7 mutations in leukemic cells mediate NOTCH pathway activation and resistance to gamma-secretase inhibitors. J Exp Med 204, 1813–1824, doi: 10.1084/jem.20070876 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasca J. et al. Loss of FBXW7 and accumulation of MCL1 and PLK1 promote paclitaxel resistance in breast cancer. Oncotarget, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10481 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eto K. et al. The sensitivity of gastric cancer to trastuzumab is regulated by the miR-223/FBXW7 pathway. Int J Cancer 136, 1537–1545, doi: 10.1002/ijc.29168 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugan A. K., Munirajan A. K. & Tsuchida N. Genetic deregulation of the PIK3CA oncogene in oral cancer. Cancer Lett 338, 193–203, doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.04.005 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick D. K. et al. Mutations of PIK3CA in anaplastic oligodendrogliomas, high-grade astrocytomas, and medulloblastomas. Cancer Res 64, 5048–5050, doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1170 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels Y. et al. High frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science 304, 554, doi: 10.1126/science.1096502 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z. C. et al. Oncogene mutational profile in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 7, 457–467, doi: 10.2147/OTT.S58791 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou C. C., Chou M. J. & Tzen C. Y. PIK3CA mutation occurs in nasopharyngeal carcinoma but does not significantly influence the disease-specific survival. Med Oncol 26, 322–326, doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9124-5 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Or Y. Y., Hui A. B., Tam K. Y., Huang D. P. & Lo K. W. Characterization of chromosome 3q and 12q amplicons in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines. Int J Oncol 26, 49–56 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arjumand W. et al. Phosphatidyl inositol-3 kinase (PIK3CA) E545K mutation confers cisplatin resistance and a migratory phenotype in cervical cancer cells. Oncotarget, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10955 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta C., Paglino C. & Mosca A. Targeting PI3K/Akt/mTOR Signaling in Cancer. Front Oncol 4, 64, doi: 10.3389/fonc.2014.00064 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels Y. et al. Mutant PIK3CA promotes cell growth and invasion of human cancer cells. Cancer Cell 7, 561–573, doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.014 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janku F. et al. Assessing PIK3CA and PTEN in early-phase trials with PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibitors. Cell Rep 6, 377–387, doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.12.035 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janku F. et al. PIK3CA mutations in advanced cancers: characteristics and outcomes. Oncotarget 3, 1566–1575, doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.716 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janku F. et al. PIK3CA mutations in patients with advanced cancers treated with PI3K/AKT/mTOR axis inhibitors. Mol Cancer Ther 10, 558–565, doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0994 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covassin L. D. et al. A genetic screen for vascular mutants in zebrafish reveals dynamic roles for Vegf/Plcg1 signaling during artery development. Dev Biol 329, 212–226, doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.02.031 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson N. D., Mugford J. W., Diamond B. A. & Weinstein B. M. phospholipase C gamma-1 is required downstream of vascular endothelial growth factor during arterial development. Genes Dev 17, 1346–1351, doi: 10.1101/gad.1072203 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao H. J. et al. Absence of erythrogenesis and vasculogenesis in Plcg1-deficient mice. J Biol Chem 277, 9335–9341, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109955200 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lattanzio R., Piantelli M. & Falasca M. Role of phospholipase C in cell invasion and metastasis. Adv Biol Regul 53, 309–318, doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2013.07.006 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto K. K. & Andrulis I. L. Atypical protein kinase C zeta: potential player in cell survival and cell migration of ovarian cancer. PLoS One 10, e0123528, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123528 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Peruta M., Giagulli C., Laudanna C., Scarpa A. & Sorio C. RHOA and PRKCZ control different aspects of cell motility in pancreatic cancer metastatic clones. Mol Cancer 9, 61, doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-61 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S. & Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell 109 Suppl, S81–96 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo M. W. & Baldwin A. S. The transcription factor NF-kappaB: control of oncogenesis and cancer therapy resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta 1470, M55–62 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X. D. & Sun S. C. Targeting signaling factors for degradation, an emerging mechanism for TRAF functions. Immunol Rev 266, 56–71, doi: 10.1111/imr.12311 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung G. T. et al. Constitutive activation of distinct NF-κB signals in EBV-associated nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Pathol 231, 311–322, doi: 10.1002/path.4239 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao G., Zhang M., Harhaj E. W. & Sun S. C. Regulation of the NF-kappaB-inducing kinase by tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 3-induced degradation. J Biol Chem 279, 26243–26250, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403286200 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni C. Z. et al. Key molecular contacts promote recognition of the BAFF receptor by TNF receptor-associated factor 3: implications for intracellular signaling regulation. J Immunol 173, 7394–7400 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. et al. Structurally distinct recognition motifs in lymphotoxin-beta receptor and CD40 for tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF)-mediated signaling. J Biol Chem 278, 50523–50529, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309381200 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni C. Z. et al. Molecular basis for CD40 signaling mediated by TRAF3. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97, 10395–10399 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lun M., Zhang P. L., Siegelmann-Danieli N., Blasick T. M. & Brown R. E. Intracellular inhibitory effects of Velcade correlate with morphoproteomic expression of phosphorylated-nuclear factor-kappaB and p53 in breast cancer cell lines. Ann Clin Lab Sci 35, 15–24 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. A., Zhang S., Yin Q. & Zhang J. Quercetin induces human colon cancer cells apoptosis by inhibiting the nuclear factor-kappa B Pathway. Pharmacogn Mag 11, 404–409, doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.153096 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunwoo J. B. et al. Novel proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits activation of nuclear factor-kappa B, cell survival, tumor growth, and angiogenesis in squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 7, 1419–1428 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes C. J., Li F., Talukder A. H. & Kumar R. Growth factor regulation of a 26S proteasomal subunit in breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 11, 2868–2874, doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1989 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson P. G., Hideshima T., Mitsiades C. & Anderson K. Proteasome inhibition in hematologic malignancies. Ann Med 36, 304–314 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robak T. et al. Bortezomib-based therapy for newly diagnosed mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 372, 944–953, doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412096 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W. et al. Id-1 and the p65 subunit of NF-κB promote migration of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells and are correlated with poor prognosis. Carcinogenesis 33, 810–817, doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs027 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. et al. Association of nuclear factor κB expression with a poor outcome in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Med Oncol 28, 1338–1342, doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9571-7 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong J. H. et al. A small molecule inhibitor of NF-kappaB, dehydroxymethylepoxyquinomicin (DHMEQ), suppresses growth and invasion of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) cells. Cancer Lett 287, 23–32, doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.05.022 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng T. et al. Andrographolide suppresses proliferation of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells via attenuating NF-κB pathway. Biomed Res Int 2015, 735056, doi: 10.1155/2015/735056 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strong M. J. et al. Comprehensive high-throughput RNA sequencing analysis reveals contamination of multiple nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines with HeLa cell genomes. J Virol 88, 10696–10704, doi: 10.1128/JVI.01457-14 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. Y. et al. Authentication of nasopharyngeal carcinoma tumor lines. Int J Cancer 122, 2169–2171, doi: 10.1002/ijc.23374 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugaratnam K. & Sobin L. H. Histological typing of upper respiratory tract tumors. International histological classification of tumors. Geneva 19, 32–33 (1978).

- Li H. & Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26, 589–595, doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePristo M. A. et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet 43, 491–498, doi: 10.1038/ng.806 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Li M. & Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 38, e164, doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol 29, 24–26, doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng P. C. & Henikoff S. Accounting for human polymorphisms predicted to affect protein function. Genome Res 12, 436–446, doi: 10.1101/gr.212802 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adzhubei I. A. et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods 7, 248–249, doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang D. W. et al. The DAVID Gene Functional Classification Tool: a novel biological module-centric algorithm to functionally analyze large gene lists. Genome Biol 8, R183, doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-9-r183 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.