Abstract

Previous genetic association studies have reported a possible role of the dopamine transporter (DAT, gene symbol: SLC6A3) gene in the etiology of alcohol dependence, but the results were conflicting with each other. We conducted a pooled analysis of published population-based case–control genetic studies investigating associations between polymorphisms in SLC6A3 and alcohol dependence. We also explored whether geographic area, ethnicity, gender, and diagnostic criteria moderated any association by using stratified analysis. Through combining 13 studies with 2483 cases and 1753 controls, the 40-base pair variable number tandem repeat (VNTR) in the 3′ un-translated region, the well studied polymorphism in SLC6A3, did not show any association with alcohol dependence in general or in stratified analyses according to geographic area, ethnicity, gender, and diagnostic criteria. Due to limited studies focused on polymorphisms in other regions of the SLC6A3 gene, we cannot rule out the role of the SLC6A3 gene in the involvement of the genetic risk of alcohol dependence. Further clarification of the genetic role of SLC6A3 in the susceptibility to alcohol dependence should be centered on other potential functional regions of the SLC6A3 gene.

Keywords: Alcohol dependence, Dopamine transporter, Genetic polymorphism, Linkage disequilibrium

1. Introduction

Alcohol dependence is one of the most prevalent mental health problems in the USA. The prevalence of lifetime and 12-month alcohol dependence in the USA was 12.5% and 3.8% (Hasin et al., 2007). Estimation of genetic effects on alcohol dependence is as high as 50 to 70% in both men and women, as is shown by numerous twin and adoption studies (Goldman et al., 2005; Pagan et al., 2006). In attempts to identify the genetic risks for alcohol dependence, genes involved in dopaminergic system have been paid much attention during the past twenty years. As is known, alcohol may activate the dopaminergic system, which in turn is associated with positive reinforcement (Berridge and Robinson, 1998). Therefore, genetic variants regulating genes coding for proteins involved in dopamine neurotransmission might account for different responses to alcohol or might contribute to individual variation in alcohol dependence (Persico et al., 1993).

Essential in dopamine regulation is the dopamine transporter (DAT1, gene symbol: SLC6A3). SLC6A3 is a 12-membrane domain Na+/Cl−-dependent transport protein, with the responsibility for the reuptake of extracellular synaptic dopamine into presynaptic neurons, and hereby termination of dopaminergic neurotransmission (Giros et al., 1992). As such, dopaminergic reward circuits are likely to function differently with different expression levels of SLC6A3 (Drgon et al., 2006), which implies the SLC6A3 gene is a potential candidate in clinical studies on alcohol dependence.

The biological mechanism under which SLC6A3 availability is regulated in the brain is still unclear. Brain imaging studies discover that SLC6A3 expression levels may be affected by alcohol consumption. Two studies reported that SLC6A3 levels were significantly lower in the striatum of alcohol-dependent humans and monkeys than in controls, but returned to normal levels after a period of abstinence (Laine et al., 1999; Mash et al., 1996). While two other studies did not find reductions in SLC6A3 levels in the brains of alcoholics when compared with controls (Heinz et al., 1998; Volkow et al., 1996), although this might be related to the fact that measurements were carried out up to several weeks after withdrawal of alcohol, in which the expression levels of SLC6A3 may have already returned to normal.

The availability of SLC6A3 in the brain may be dependent on genetic variation. SLC6A3 gene is mapped on chromosome 5p15.3 with 15 exons separated by 14 introns spanning more than 65 kb. The protein-coding portion begins within exon 2 and ends near the beginning of exon 15 (Banno et al., 2001). This coding region presents strong conservation and the polymorphisms within the coding region represent either silent nucleotide changes or rare conservative amino acid substitutions (Grünhage et al., 2000), indicating that individual differences in SLC6A3 expression must arise from regulatory sequences. Lin and Uhl (2003) observed the effects of protein-coding variants V55A and V382A in the human dopamine transporter gene on expression and uptake activities in vitro. Drgon et al. (2006) reported common human 5′ dopamine transporter haplotypes yield varying expression levels in vivo. Greenwood and Kelsoe (2003) identified a strong core promoter extending from −251 to +63 in the genomic sequence of the SLC6A3 gene and suggested the presence of repressor elements in the 5′-upstream region and within intron 1 (Xu et al., 2010).

The genetic polymorphism of interest in most genetic association studies on alcohol dependence, however, is a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR) of 40 bp in the 3′ un-translation region. For the VNTR, numbers ranging from 3 to 16 have been described, with the 9-and 10-repeat alleles being the most common variants (Banno et al., 2001; Vandenbergh et al., 1992). Several studies have demonstrated ethnic differences in SLC6A3 VNTR frequency distributions (Kang et al., 1999; Mitchell et al., 2000). The results of human genetic association studies investigating the relationship between this VNTR and alcohol dependence have been equivocal. Since the VNTR is located in the 3′-UTR of the gene, outside the open reading frame of the gene, allelic variants do not result in structural or functional differences in the SLC6A3 protein. Nonetheless, research suggests that the SLC6A3 VNTR is able to regulate specific gene functioning by influencing levels of expression. As such, SLC6A3 expression may be influenced by alteration in the length or sequence of the VNTR (Conne et al., 2000). It is also likely that this VNTR is in linkage disequilibrium with other susceptibility loci within the gene. A SNP in the 3′-UTR of SLC6A3 consists of a G to A mutation at position 2319 in SLC6A3 cDNA has also been investigated with the association of alcohol dependence by Ueno et al. (1999a,b) and Choi et al. (2006a,b), but the two studies with limited sample size reported conflicting results.

To identify a real association, we performed pooled analysis of multicenter genetic association studies to determine whether the failure to identify any real association is attributable to: 1) the low power of individual studies to detect a small effect; 2) etiological heterogeneity arose from potential confounding factors.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data collection

To identify studies eligible for this collaborative analysis, we conducted a computerized search on Medline and the Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure Database from 1995 up to August 2010. Keywords used were ‘dopamine transporter’, ‘DAT1’, ‘DAT’, ‘SLC6A3’, combined with ‘alcohol’, ‘dependence’ and ‘alcoholism’. We also used reference lists from identified articles and reviews to find additional original reports not indexed by the search engine.

2.2. Data synthesis

Only those studies examining at least one genetic polymorphism within or near the SLC6A3 gene locus were included in this pooled analysis. In addition, studies had to meet all of the following criteria: (1) be published in a peer-reviewed journal; (2) present original data on genotype frequencies, and genotype frequencies were used to calculate whether or not they deviated significantly from Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) among control subjects (re-calculated p<0.05) or be able to get information from the corresponding authors regarding whether or not the genotype distribution in control subjects deviated significantly from HWE; (3) independence from other studies (i.e., studies that included and re-analyzed a previously published data set were not regarded as independent; in this case, only the study composed of larger sample size was included in the pooled analysis); and (4) sufficient data to calculate an effect size (Odds Ratio). Because of the small number of studies using a family-based design, only case–control studies were included in the pooled analysis. For the case–control studies under consideration, the following variables were abstracted from each study according to a fixed protocol: the first author, published year, study design, geographic area, ethnicity, diagnostic criteria, age, gender component, definition and sample size, status of HWE, and allele distribution. All of the inclusion criteria were described in our previous studies (Xu et al., 2006, 2007, 2010; Xu and He, 2010).

2.3. Statistic analysis

Analytic approaches were described in our previous studies (Xu et al., 2006, 2007, 2010; Xu and He, 2010). In brief, for each of these included studies, two-by-two tables were constructed, in which subjects were classified by diagnostic category (case or control) and allelic frequency (calculated predefined risk allele vs. other alleles). A summary odds ratio (OR) was calculated for each of these two-by-two tables, indicating the strength of association between alcohol dependence and the corresponding risk allele. The summary (calculated pooled) ORs were obtained by random effects method of DerSimonian and Laird (1986) (the random effects method yields wider confidence intervals (CIs) when heterogeneity exists: otherwise fixed and random effects methods’ estimates are similar), and 95% CIs were constructed by using Woolf’s (1955) method. The significance of the pooled OR was determined by the z-test. Prior to the pooling procedure, a χ2-based Q statistic test was performed in order to assess the heterogeneity within the group of odds ratios. Sensitivity analysis, which determines the influence of individual studies on the pooled OR, was determined by sequentially removing each study and recalculating the pooled OR and 95% CI. Publication bias was assessed by the method of Egger et al. (1997), which used a linear regression approach to measure funnel plot asymmetry on the natural logarithm of the OR. The standard normal deviate of the odds ratio (defined as the ln (OR) divided by its standard error, termed ‘SND’) is regressed on the precision (defined as the inverse of the standard error of the odds ratio) (equation: SND=a+b×Precision). The slope (b) of the regression line indicates the size and direction of effect. If there is an asymmetry, with smaller studies showing effects that differ systematically from larger studies, the regression line will not run through the origin. The intercept (a) provides a measure of asymmetry (the larger its deviation from zero, the more pronounced the asymmetry). The significance of the intercept (a) was determined by the t-test. Stratified meta-analyses were conducted to assess any moderating effects of geographic area, ethnicity, gender, and diagnostic criteria on odds ratio derived from each study. The type I error rate was set at 0.05. P-values are two-tailed. All the previously discussed statistical analyses were conducted by using Stata 10.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

In order to evaluate the effects of genetic linkage disequilibrium (LD) patterns and the difference in genetic structure between Caucasian and East Asian populations on the SLC6A3 gene Locus and susceptibility to alcohol dependence, genotype data for 30 CEPH trios and 90 un-related East Asian subjects (45 JPT and 45 CHB) from the hapmap project (http://www.hapmap.org) were used for construction of haplotype, counting and LD block defining based on the measure of pair-wise R2 using Haploview software (Barrett et al., 2005).

3. Results

The application of foregoing criteria yielded 23 studies (Ueno et al., 1999a,b; Choi et al., 2006a,b; Muramatsu and Higuchi, 1995; Sander et al., 1997; Dobashi et al., 1997; Parsian and Zhang, 1997; Schmidt et al., 1998; Franke et al., 1999; Ueno et al., 1999a,b; Vandenbergh et al., 2000; Heinz et al., 2000; Bau et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2001; Wernicke et al., 2002; Gorwood et al., 2003; Limosin et al., 2004; Foley et al., 2004; Köhnke et al., 2005; Le Strat et al., 2008; Grzywacz and Samochowiec, 2008; Lind et al., 2009; Wu et al., 2009). After discarding the studies: 1) overlapping references; 2) insufficient and equivocal data available after contacting the corresponding authors; 3) significant deviation from HWE among control subjects (self-reported or re-calculated p < 0.05), 16 studies were left. Because the analytic difference between family-based study design and case–control study design, one article based on family-based study design was excluded. Because most of the included studies but 2 (Ueno et al., 1999a,b; Choi et al., 2006a,b) were focused on the VNTR, there was no power for pooled analysis of other polymorphisms. Finally, 13 studies (Muramatsu and Higuchi, 1995; Sander et al., 1997; Dobashi et al., 1997; Parsian and Zhang, 1997; Ueno et al., 1999a,b; Heinz et al., 2000; Bau et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2001; Wernicke et al., 2002; Gorwood et al., 2003; Köhnke et al., 2005; Le Strat et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2009) with a combined sample of 2483 cases and 1753 controls focused on the VNTR were included in current pooled analysis, as listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of case–control studies on the effect of the SLC6A3 40-bp VNTR on risk of alcohol dependence.

| Study | Publication date | Geographic area | Ethnicity | Diagnostic criteria | Gender component | No. of cases | No. of controls | Status of HWEa | Allele distribution in cases

|

Allele distribution in controls

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9-repeat | 10-repeat | Other | 9-repeat | 10-repeat | Other | |||||||||

| Muramatsu et al. | 1995 | Japan | East Asian | DSM-III-R | Mixed | 235 | 212 | Self-reported | 24 | 380 | 20 | 29 | 424 | 17 |

| Sander et al. | 1997 | Germany | Caucasian | ICD-10 | Mixed | 293 | 93 | Re-calculated p=0.21 | 145 | 437 | 4 | 35 | 147 | 4 |

| Dobashi et al. | 1997 | Japan | East Asian | DSM-III-R | Mixed | 78 | 117 | Self-reported | 5 | 146 | 5 | 18 | 211 | 5 |

| Parsian et al. | 1997 | USA | Caucasian | DSM-III-R | Mixed | 159 | 92 | Self-reported | 84 | 228 | 6 | 46 | 127 | 1 |

| Ueno et al. | 1999 | Japan | East Asian | DSM-III-R | Mixed | 124 | 107 | Re-calculated p=0.45 | 18 | 221 | 9 | 8 | 199 | 7 |

| Heinz et al. | 2000 | USA | Caucasian | DSM-IV | Mixed | 17 | 12 | Re-calculated p=0.49 | 8 | 26 | 0 | 4 | 20 | 0 |

| Bau et al. | 2001 | Brazil | Brazilian | DSM-III-R | Male | 228 | 224 | Re-calculated p=0.77 | 98 | 352 | 6 | 110 | 332 | 6 |

| Chen et al. | 2001 | Taiwan | East Asian | DSM-III-R | Mixed | 353 | 203 | Re-calculated p=0.36 | 65 | 641 | 0 | 39 | 367 | 0 |

| Wernicke et al. | 2002 | Germany | Caucasian | ICD-10 | Mixed | 351 | 336 | Self-reported | 189 | 513 | 0 | 176 | 497 | 0 |

| Gorwood et al. | 2003 | France | Caucasian | DSM-III-R | Male | 120 | 65 | Re-calculated p=0.39 | 72 | 168 | 0 | 44 | 86 | 0 |

| Köhnke et al. | 2005 | Germany | Caucasian | DSM-IV | Mixed | 216 | 102 | Re-calculated p=0.21 | 104 | 320 | 9 | 33 | 165 | 6 |

| Le Strat et al. | 2008 | France | Caucasian | DSM-IV | Mixed | 232 | 121 | Re-calculated p=0.872 | 118 | 346 | 0 | 77 | 165 | 0 |

| Wu et al. | 2009 | China | East Asian | DSM-IV | Mixed | 80 | 70 | Re-calculated p=0.10 | 7 | 79 | 6 | 12 | 67 | 2 |

The genotype distributions in control subjects of all of the included studies were not severely deviated from Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium. Estimation of the status of deviation of Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium is based on two approaches: 1) if the original genotype distribution information was presented in the included original report, the p-value of Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium test was calculated and presented in the bracket; 2) if the original genotype distribution information was not presented in the included original report, we contacted in corresponding author of first author and then self-reported status of deviation from Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium was given.

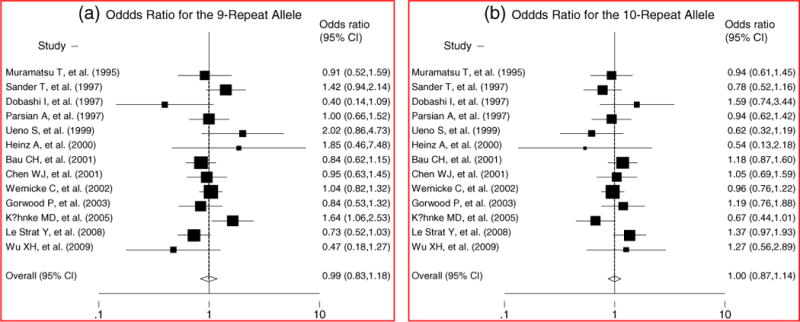

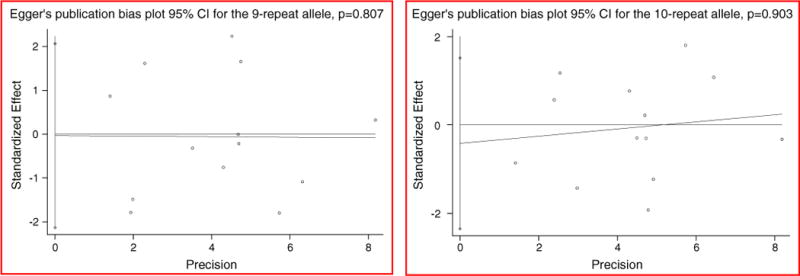

The pooled ORs and 95% CIs for the case-control studies of the VNTR were not significant (for 9-repeat allele: OR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.83–1.18, p = 0.91, see Fig. 1(a); for 10-repeat allele: OR = 1.00, 95% CI: 0.87–1.14, p = 0.94, see Fig. 1(b)). There was no evidence for either significant heterogeneity or publication bias in these analyses (for 9- repeat allele: heterogeneity χ2 = 21.71 (d.f. = 12), p = 0.041, and Egger’s publication bias P = 0.807(see Fig. 2(a)); for 10-repeat allele: heterogeneity χ2 = 15.05 (d.f. = 12), p = 0.239, and Egger’s publication bias P = 0.903(see Fig. 2(b))). The sensitivity analytic results are shown in Table 2. In general, no individual study was found to be significantly biasing the pooled results. Considering the influences of geographic area, ethnicity, gender, status of HWE, and diagnostic criteria on the pooled results, we performed stratified analyses for each of the confounding factors. The stratified analytic results are shown in Table 3. We found no positively pooled results for each of the stratified analyses, indicating that the negative results in the general pooled analysis were not confounded by geographic area, ethnicity, gender, status of HWE, and diagnostic criteria.

Fig. 1.

Collaborative analysis of the effect of the SLC6A3 40-bp VNTR on risk of alcohol dependence.

Fig. 2.

Egger’s test for publication bias of studies on the effect of the SLC6A3 40-bp VNTR on risk of alcohol dependence.

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis of the effect of the SLC6A3 40-bp VNTR on risk of alcohol dependence.

| Study omitted | Publication date | OR (95%CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 9-repeat | 10-repeat | ||

| Muramatsu et al. | 1995 | 1.00 (0.82–1.20) | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) |

| Sander et al. | 1997 | 0.95 (0.80–1.14) | 1.02 (0.89–1.17) |

| Dobashi et al. | 1997 | 1.01 (0.86–1.20) | 0.98 (0.86–1.12) |

| Parsian et al. | 1997 | 0.99 (0.81–1.20) | 1.00 (0.86–1.16) |

| Ueno et al. | 1999 | 0.97 (0.81–1.15) | 1.01 (0.89–1.16) |

| Heinz et al. | 2000 | 0.98 (0.82–1.17) | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) |

| Bau et al. | 2001 | 1.01 (0.83–1.23) | 0.97 (0.84–1.12) |

| Chen et al. | 2001 | 0.99 (0.82–1.21) | 0.99 (0.85–1.15) |

| Wernicke et al. | 2002 | 0.98 (0.80–1.21) | 1.00 (0.85–1.17) |

| Gorwood et al. | 2003 | 1.01 (0.83–1.22) | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) |

| Köhnke et al. | 2005 | 0.94 (0.80–1.11) | 1.03 (0.92–1.16) |

| Le Strat et al. | 2008 | 1.03 (0.86–1.23) | 0.96 (0.85–1.09) |

| Wu et al. | 2009 | 1.01 (0.85–1.20) | 0.99 (0.86–1.14) |

Table 3.

Stratified analysis of the effect of the SLC6A3 40-bp VNTR on risk of alcohol dependence.

| Subgroup (no. of studies) | Analysis for 9-related allele

as predefined allele |

Analysis for 10-related allele

as predefined allele |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | Significance test |

Test (s) of heterogeneity

|

OR (95%CI) | Significance test |

Test (s) of heterogeneity

|

|||||

| z | p-value | Q (D.F.) | P-value | z | p-value | Q (D.F.) | P-value | |||

| Geographic area | ||||||||||

| Europe (5) | 1.07(0.81–1.41) | 0.47 | 0.640 | 11.36 | 0.023 | 0.97(0.76–1.23) | 0.28 | 0.783 | 9.02 | 0.061 |

| North America (2) | 1.05(0.70–1.57) | 0.24 | 0.807 | 0.69 | 0.406 | 0.90(0.61–1.33) | 0.54 | 0.590 | 0.55 | 0.457 |

| Asia (5) | 0.86(0.56–1.34) | 0.65 | 0.513 | 7.64 | 0.106 | 1.00(0.78–1.28) | 0.02 | 0.981 | 3.91 | 0.418 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Caucasian (7) | 1.07(0.86–1.33) | 0.58 | 0.561 | 12.05 | 0.061 | 0.95(0.79–1.16) | 0.48 | 0.634 | 9.72 | 0.137 |

| East Asian (5) | 0.86(0.56–1.34) | 0.65 | 0.513 | 7.64 | 0.106 | 1.00(0.78–1.28) | 0.02 | 0.981 | 3.91 | 0.418 |

| Others (1) | 0.84(0.62–1.15) | 1.09 | 0.274 | NA | NA | 1.18(0.87–1.60) | 1.08 | 0.280 | NA | NA |

| Diagnostic criteria | ||||||||||

| DSM-III-R (7) | 0.91(0.75–1.10) | 1.00 | 0.316 | 6.52 | 0.368 | 1.06(0.89–1.24) | 0.61 | 0.541 | 5.05 | 0.537 |

| DSM-IV(4) | 0.99(0.54–1.81) | 0.04 | 0.965 | 11.14 | 0.011 | 0.97(0.60–1.57) | 0.13 | 0.894 | 7.98 | 0.046 |

| ICD-10(2) | 1.16(0.87–1.55) | 1.00 | 0.319 | 1.62 | 0.203 | 0.91(0.74–1.12) | 0.91 | 0.362 | 0.79 | 0.373 |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Male (2) | 0.84(0.65–1.09) | 1.33 | 0.183 | 0 | 0.988 | 1.19(0.92–1.53) | 1.32 | 0.186 | 0 | 0.973 |

| Mixed (11) | 1.03(0.83–1.28) | 0.29 | 0.772 | 19.78 | 0.031 | 1.03(0.83–1.28) | 0.29 | 0.772 | 19.78 | 0.031 |

| Status of HWE | ||||||||||

| Re-calculated (9) | 1.03(0.80–1.32) | 0.24 | 0.811 | 18.35 | 0.019 | 0.98(0.80–1.20) | 0.15 | 0.881 | 13.35 | 0.100 |

| Self-reported (4) | 0.97(0.78–1.20) | 0.29 | 0.772 | 3.37 | 0.338 | 0.98(0.82–1.17) | 0.22 | 0.823 | 1.63 | 0.653 |

4. Discussion

The results of this combined-analysis indicate that the 9- and 10- repeat alleles of the 40-base-pair VNTR of the SLC6A3 gene are not associated with alcohol dependence. The pooled OR for the 9-repeat allele was 0.99, and the OR for the 10-repeat allelewas 1.00. None of the analyses reached statistical significance, in spite of a power greater than 80% to detect a significant OR as small as 1.3. Lack of significance attributable to the negative effects of single large studies or to heterogeneity between the studies or to potential confounding factors (geographic area, ethnicity, gender, and diagnostic criteria) was excluded. The findings of this pooled analysis are limited by the fact that they rely only on case–control studies, which are more susceptible than family-based studies to sampling bias introduced by potential differences between patient and control groups (Gamma et al., 2005). There was one family-based study, which investigated the relation between the VTNR polymorphism and alcohol dependence and found no association between allele frequencies for this VNTR of the SLC6A3 gene and alcohol dependence in a sample of 100 nuclear families. To explore the relationship between the genetic variants of SLC6A3 and alcohol dependence-related phenotypes, such as alcohol withdrawal seizures and delirium tremens, is out of the scope of our study. Several case–control studies (Gorwood et al., 2003;Wernicke et al., 2002) have explored the effects of the 40-bp VNTR on alcohol-withdraw symptoms. Even though the final conclusion cannot be drawn due to limited studies reported with limited sample size and conflicting findings, we cannot rule out the possibility that different percentages of the components of alcohol-withdraw symptoms in the cases of alcohol dependence included in our pooled analysis may bias our pooled results.

For other genetic polymorphisms within or near the SLC6A3 gene, we did not conduct pooled analyses due to limited number of studies available (less than three studies for a given genetic polymorphism). But we cannot rule out the role of these genetic variants in the involvement of alcohol dependence, especially those located in the promoter region or other functional regions of the SLC6A3 gene with biological evidence. We identified two studies (Ueno et al., 1999a,b; Choi et al., 2006a,b) with 235 cases and 230 controls in which the G2319A genetic polymorphism was investigated, but the pooled sample size had a statistic power of 50% to detect a significant OR as small as 1.5, indicating that it warrants to enlarge sample size in order to detect a true association of this genetic polymorphism. Further analysis of linkage disequilibrium patterns measured by R2 on the Haploview software and the analysis of genetic structure on the SLC6A3 gene locus in both Caucasian and Eastern Asian populations, we found that 50 polymorphic markers were genotyped by the hapmap project. There is apparently different in genetic structure between Caucasian population and East Asian population. In Caucasian population, the 40-bp VNTR is located in the first haplotype block; while in East Asian population, the surrounding region of the 40-bp VNTR is highly recombinant. The linkage disequilibrium patterns in both Caucasian and Eastern Asian populations suggest that there might be other haplotype blocks associated with alcohol dependence.

As suggested in a recent review article (van der Zwaluw et al., 2009), limited sample size in individual study (disregarding gene–gene and gene–environment interactions and ignoring psychiatric co-morbidity in case and control subjects) are the shortcomings of reported genetic studies on SLC6A3 and alcohol dependence. In addition, DNA methylation in specific regions is a potential relevant mechanism in regulation of SLC6A3, which was also a topic of recent investigations regarding psychiatric disorders such as eating disorders and alcohol dependence (Frieling et al., 2010; Hillemacher et al., 2009). Ignoring the effects of alcohol-triggered epigenetic regulation in SLC6A3 on alcohol dependence is also a weakness of established studies.

In summary, considering the cumulative evidence from 13 case–control studies, it seems unlikely that the 40-bp VNTR in the 3′UTR of the SLC6A3 gene influences risk for alcohol dependence. Further clarification of the role of SLC6A3 in the susceptibility to alcohol dependence should be centered on: 1) other potential functional regions of the SLC6A3 gene; 2) exploring gene–gene and gene–environment interactions; 3) sub-clinic analysis; 4) the sensitivity to regulation by epigenetic mechanisms as evident from the GC-bias composition of the SLC6A3 and numerous intragenetic CpG islands (Shumay et al., 2010). Integrating genetic with environmental exposure-triggered epigenetic factors is necessary to understand the etiology of alcohol dependence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the investigators who kindly provided their original data to us in this project.

Funding/Support

This work was supported by the U.S.A. National Institutes of Health grant R01DA021409.

Role of the Funding Source

The sponsors of the study had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report.

Abbreviations

- DAT1

Dopamine Transporter

- VNTR

Variable Number of Tandem Repeats

- UTR

Un-Translated Region

- HWE

Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium

- OR

Odds Ratio

- CI

Confidence Interval

- LD

Linkage Disequilibrium

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.11.001.

Footnotes

Contributors

Mingqing Xu and Z. Carl Lin initiated and designed the study. Mingqing Xu collected and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. All investigators contributed to the interpretation, and revision.

Conflict of Interest Statement

None declared.

References

- Banno MJ, Michelhaugh SK, Wang J, Sacchetti P. The human dopamine transporter gene: gene organization, transcriptional regulation, and potential involvement in neuropsychiatric disorders. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;11:449–55. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(01)00122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;2:263–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bau CH, Almeida S, Costa FT, Garcia CE, Elias EP, Ponso AC, et al. DRD4 and DAT1 as modifying genes in alcoholism: interaction with novelty seeking on level of alcohol consumption. Mol Psychiatry. 2001;6:7–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC, Robinson TE. What is the role of dopamine in reward: hedonic impact, reward learning, or incentive salience. Brain Res Rev. 1998;28:309–69. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WJ, Chen CH, Huang J, Hsu YP, Seow SV, Chen CC, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of the promoter region of dopamine D2 receptor and dopamine transporter genes and alcoholism among four aboriginal groups and Han Chinese in Taiwan. Psychiatr Genet. 2001;11:187–95. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200112000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi IG, Kee BS, Son HG, Ham BJ, Yang BH, Kim SH, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase, dopamine and serotonin transporters in familial and non-familial alcoholism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006a;16:123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi IG, Kee BS, Son HG, Ham BJ, Yang BH, Kim SH, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of alcohol and aldehyde dehydrogenase, dopamine and serotonin transporters in familial and non-familial alcoholism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006b;16:123–8. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conne B, Stutz A, Vassalli JD. The 3′ untranslated region of messenger RNA: a molecular ‘hotspot’ for pathology? Nat Med. 2000;6:637–41. doi: 10.1038/76211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobashi I, Inada T, Hadano K. Alcoholism and gene polymorphisms related to central dopaminergic transmission in the Japanese population. Psychiatr Genet. 1997;7:87–91. doi: 10.1097/00041444-199722000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drgon T, Lin Z, Wang GJ, Fowler J, Pablo J, Mash DC, et al. Common human 5′ dopamine transporter (SLC6A3) haplotypes yield varying expression levels in vivo. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26:875–89. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9014-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley PF, Loh EW, Innes DJ, Williams SM, Tannenberg AE, Harper CG, et al. Association studies of neurotransmitter gene polymorphisms in alcoholic Caucasians. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1025:39–46. doi: 10.1196/annals.1316.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke P, Schwab SG, Knapp M, Gänsicke M, Delmo C, Zill P, et al. DAT1 gene polymorphism in alcoholism: a family-based association study. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:652–4. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieling H, Römer KD, Scholz S, Mittelbach F, Wilhelm J, De Zwaan M, Jacoby G, Kornhuber J, Hillemacher T, Bleich S. Epigenetic dysregulation of dopaminergic genes in eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2010;43(7):577–83. doi: 10.1002/eat.20745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamma F, Faraone SV, Glatt SJ, Yeh YC, Tsuang MT. Meta-analysis shows schizophrenia is not associated with the 40-base-pair repeat polymorphism of the dopamine transporter gene. Schizophr Res. 2005;73:55–8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giros B, EI Mestikawy S, Godinot N, Zheng K, Han H, Yang-Feng T, et al. Cloning, pharmacological characterization, and chromosome assignment of the human dopamine transporter. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42:383–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman D, Oroszi G, Ducci F. The genetics of addictions: uncovering the genes. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:521–32. doi: 10.1038/nrg1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorwood P, Limosin F, Batel P, Hamon M, Adès J, Boni C. The A9 allele of the dopamine transporter gene is associated with delirium tremens and alcohol-withdrawal seizure. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:85–92. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood TA, Kelsoe JR. Promoter and intronic variants affect the transcriptional regulation of the human dopamine transporter gene. Genomics. 2003;82:511–20. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(03)00142-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grünhage F, Schulze TG, Müller DJ, Lanczik M, Franzek E, Albus M, et al. Systematic screening for DNA sequence variation in the coding region of the human dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5:275–82. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzywacz A, Samochowiec J. Case–control, family based and screening for DNA sequence variation in the dopamine transporter gene polymorphism SLC6A3 1 in alcohol dependence. Psychiatr Pol. 2008;42:443–52. Polish. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin DS, Stinson FS, Ogburn E, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:830–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.7.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Ragan P, Jones DW, Hommer D, Williams W, Knable MB, et al. Reduced central serotonin transporters in alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1544–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.11.1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Goldman D, Jones DW, Palmour R, Hommer D, Gorey JG, et al. Genotype influences in vivo dopamine transporter availability in human striatum. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:133–9. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillemacher T, Frieling H, Hartl T, Wilhelm J, Kornhuber J, Bleich S. Promoter specific methylation of the dopamine transporter gene is altered in alcohol dependence and associated with craving. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43(4):388–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang AM, Palmatier MA, Kidd KK. Global variation of a 40-bp VNTR in the 3′-untranslated region of the dopamine transporter gene (SLC6A3) Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:151–60. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00101-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köhnke MD, Batra A, Kolb W, Köhnke AM, Lutz U, Schick S, et al. Association of the dopamine transporter gene with alcoholism. Alcohol Alcohol. 2005;40:339–42. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laine TP, Ahonen A, Torniainen P, Heikkilä J, Pyhtinen J, Räsänen P, et al. Dopamine transporters increase in human brain after alcohol withdrawal. Mol Psychiatry. 1999;4(189–91):104–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Strat Y, Ramoz N, Pickering P, Burger V, Boni C, Aubin HJ, et al. The 3′ part of the dopamine transporter gene DAT1/SLC6A3 is associated with withdrawal seizures in patients with alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32:27–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limosin F, Loze JY, Boni C, Fedeli LP, Hamon M, Rouillon F, et al. The A9 allele of the dopamine transporter gene increases the risk of visual hallucinations during alcohol withdrawal in alcohol-dependent women. Neurosci Lett. 2004;362:91–4. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z, Uhl GR. Human dopamine transporter gene variation: effects of protein coding variants V55A and V382A on expression and uptake activities. Pharmacogenomics J. 2003;3:159–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind PA, Eriksson CJ, Wilhelmsen KC. Association between harmful alcohol consumption behavior and dopamine transporter (DAT1) gene polymorphisms in a male Finnish population. Psychiatr Genet. 2009;19:117–25. doi: 10.1097/YPG.0b013e32832a4f7b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash DC, Staley JK, Doepel FM, Young SN, Ervin FR, Palmour RM. Altered dopamine transporter densities in alcohol-preferring vervet monkeys. NeuroReport. 1996;7:457–62. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199601310-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RJ, Howlett S, Earl L, White NG, McComb J, Schanfield MS, et al. Distribution of the 3′ VNTR polymorphism in the human dopamine transporter gene in world populations. Hum Biol. 2000;72:295–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muramatsu T, Higuchi S. Dopamine transporter gene polymorphism and alcoholism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;211:28–32. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagan JL, Rose RJ, Viken RJ, Pulkkinen L, Kaprio J, Dick DM. Genetic and environmental influences on stages of alcohol use across adolescence and into young adulthood. Behav Genet. 2006;36:483–97. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9062-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsian A, Zhang ZH. Human dopamine transporter gene polymorphism (VNTR) and alcoholism. Am J Med Genet. 1997;74:480–2. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19970919)74:5<480::aid-ajmg4>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persico AM, Vandenbergh DJ, Smith SS, Uhl GR. Dopamine transporter gene polymorphisms are not associated with polysubstance abuse. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;34:265–7. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90081-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander T, Harms H, Podschus J, Finckh U, Nickel B, Rolfs A, et al. Allelic association of a dopamine transporter gene polymorphism in alcohol dependence with withdrawal seizures or delirium. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(96)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt LG, Harms H, Kuhn S, Rommelspacher H, Sander T. Modification of alcohol withdrawal by the A9 allele of the dopamine transporter gene. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:474–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.4.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumay E, Fowler JS, Volkow ND. Genomic features of the human dopamine transporter gene and its potential epigenetic states: implications for phenotypic diversity. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11067. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S, Nakamura M, Mikami M, Kondoh K, Ishiguro H, Arinami T, et al. Identification of a novel polymorphism of the human dopamine transporter (DAT1) gene and the significant association with alcoholism. Mol Psychiatry. 1999a;4:552–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno S, Nakamura M, Mikami M, Kondoh K, Ishiguro H, Arinami T, et al. Identification of a novel polymorphism of the human dopamine transporter (DAT1) gene and the significant association with alcoholism. Mol Psychiatry. 1999b;4:552–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zwaluw CS, Engels RC, Buitelaar J, Verkes RJ, Franke B, Scholte RH. Polymorphisms in the dopamine transporter gene (SLC6A3/DAT1) and alcohol dependence in humans: a systematic review. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:853–66. doi: 10.2217/pgs.09.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbergh DJ, Persico AM, Hawkins AL, Griffin CA, Li X, Jabs EW, et al. Human dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) maps to chromosome 5p15.3 and displays a VNTR. Genomics. 1992;14:1104–6. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80138-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenbergh DJ, Thompson MD, Cook EH, Bendahhou E, Nguyen T, Krasowski MD, et al. Human dopamine transporter gene: coding region conservation among normal, Tourette’s disorder, alcohol dependence and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder populations. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5:283–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Hitzemann R, Ding YS, et al. Decreases in dopamine receptors but not in dopamine transporters in alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:1594–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb05936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernicke C, Smolka M, Gallinat J, Winterer G, Schmidt LG, Rommelspacher H. Evidence for the importance of the human dopamine transporter gene for withdrawal symptomatology of alcoholics in a German population. Neurosci Lett. 2002;333:45–8. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)00985-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolf B. On estimating the relation between blood group and disease. Ann Hum Genet. 1955;19:251–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1955.tb01348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XH, Zhong SR, Gao CQ, Bao JJ, Hu LP, Ruan Y, et al. Association analysis of dopamine D2 (DRD2), dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) and dopamine transporter (DAT) gene polymorphisms with alcohol dependence. Prog Mod Biomed. 2009;9:1440–2. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, He L. Convergent evidence shows a positive association of interleukin-1 gene complex locus with susceptibility to schizophrenia in the Caucasian population. Schizophr Res. 2010;120:131–42. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.02.1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu MQ, St Clair D, He L. Meta-analysis of association between ApoE epsilon4 allele and schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;84:228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu MQ, St Clair D, Ott J, Feng GY, He L. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor gene C-270 T and Val66Met functional polymorphisms and risk of schizophrenia: a moderate-scale population-based study and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2007;91:6–13. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, St Clair D, He L. Testing for genetic association between the ZDHHC8 gene locus and susceptibility to schizophrenia: an integrated analysis of multiple datasets. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(7):1266–75. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.31096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.