Abstract

Objective

The purpose is to examine the relationship between mandibular osteoradionecrosis (ORN) and chronic dysphagia in long-term oropharynx cancer (OPC) survivors and to determine the perceived symptom burden associated with ORN.

Materials and Methods

Medical records of 349 OPC patients treated with bilateral IMRT and systemic therapy were reviewed. ORN was graded using a published 4-point classification schema. Patients were considered to have chronic dysphagia if they had aspiration pneumonia, stricture or aspiration detected by fluoroscopy or endoscopy, and/or feeding tube dependence in long-term follow-up ≥ 1 year following radiotherapy. MD Anderson Symptom Inventory – Head and Neck Module (MDASI-HN) scores were analyzed in a nested cross-sectional survey sample of 118 patients.

Results

34 (9.7%, 95% CI: 6.8–13.3%) patients developed ORN and 45 (12.9%, 95% CI: 9.6–16.9%) patients developed chronic dysphagia. Prevalence of chronic dysphagia was significantly higher in ORN cases (12/34, 35%) compared to those who did not develop ORN (33/315, 11%, p<0.001). ORN grade was also significantly associated with prevalence of dysphagia (p<0.001); the majority of patients with grade 4 ORN requiring major surgery (6 patients, 75%) were found to have chronic dysphagia. Summary MDASI-HN symptom scores did not significantly differ by ORN grade. Significantly higher symptom burden was reported, however, among ORN cases compared to those without ORN for MDASI-HN swallowing (p=0.033), problems with teeth and/or gums (p=0.016) and change in activity (p=0.015) item scores.

Conclusions

ORN is associated with excess burden of chronic dysphagia and higher symptom severity related to swallowing, dentition and activity limitations.

Keywords: Head and neck cancer, oropharynx cancer, dysphagia, osteoradionecrosis, chemoradiation, symptom burden, morbidity, patient-reported outcomes

Introduction

The annual estimated incidence of oropharynx cancer is approximately 130,300 cases per year worldwide with an estimated 15,000 new cases diagnosed annually in the United States [1,2]. Over the last few decades, the incidence of oropharynx cancer has been increasing dramatically in developed countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden [3]. This rise in the incidence of oropharynx cancer is attributed to human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OPSCC) have better response to treatment and lower overall recurrence rates when compared to HPV negative OPSCC [3–5].

Treatment of OPSCC primarily involves radiotherapy and chemotherapy with the goal of preservation of anatomy and function [6]. While highly effective at curing OPSCC, radiation therapy can induce normal tissue changes that can cause a myriad of acute and chronic complications [2]. These complications can include oral mucositis, increased risk of infections, xerostomia, neuropathic pain, osteoradionecrosis (ORN) and dysphagia which can lead to significant morbidity and decreased quality of life in oropharynx cancer survivors [2,6].

One of the most common late complications of treatment affecting quality of life is dysphagia. It is estimated that 12 to 38.5% of patients treated with primary radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for locoregionally advanced stage head and neck cancer develop chronic dysphagia, when defined by chronic aspiration, stricture and/or gastrostomy dependence [6–8]. Radiation dose distributions to swallowing-critical muscle regions including the pharyngeal constrictors, suprahyoid muscles, and the larynx primarily correlate with chronic dysphagia [9–11].

ORN is a potentially severe late complication of radiation treatment for head and neck cancer. ORN is diagnosed based on clinical features and symptoms. The most accepted definition of ORN is an area of exposed bone that fails to heal after a period of 3 months, after exclusion of all other diagnoses [12,13]. Fortunately, ORN is becoming a less common complication with increased use of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). Despite a declining rate of ORN, the rate is still significant with an estimated incidence of 6.4% in head and neck cancer patients [13]. Among the risk factors for ORN, the most significant are high osseous radiation dose distributions, extraction of teeth within the field of radiation, smoking and alcohol consumption [13–15]. ORN can manifest as an asymptomatic condition to severely debilitating presentation with related pain, disfigurement and functional impairment [12]. However, the functional burden of ORN is not well characterized. Chronic dysphagia has been reported in severe cases of ORN, particularly with advanced cases requiring mandibulectomy with removal of the symphysis, but group level associations between dysphagia and ORN are limited [16]. The purpose of this retrospective study is to examine the relationship between ORN and chronic dysphagia in long-term oropharynx cancer survivors and to characterize perceived symptom burden associated with ORN. We hypothesized to detect a higher prevalence of dysphagia and higher perceived symptom burden among ORN patients.

Materials and methods

Study design and eligibility criteria

A retrospective cohort study with nested cross-sectional survey analysis was performed to characterize the functional burden of ORN. Eligibility criteria were: (1) adults greater than 18 years of age diagnosed with OPSCC; (2) treatment with definitive intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) and systemic therapy (induction and/or concurrent chemotherapy or targeted therapy); and (3) a minimum of 1-year disease free follow-up. This study comprised the same patient population as described by Hutcheson et al. (2016), with final inclusion of 349 patients [8]. All eligible patients were sampled from a prospective epidemiologic registry. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center approved the chart review, and a waiver of informed consent was obtained.

Study variables and data source

A review of the electronic medical record was used to collect demographic data, medical comorbidities, tumor and treatment variables, ORN and dysphagia endpoints.

Osteoradionecrosis measures

ORN was graded according to treatment based severity classification system first published by Tsai et al. (2012) [14]. Grade 1 ORN is defined as minimal bone exposure requiring conservative treatment only, grade 2 ORN receiving minor debridement, grade 3 ORN requiring hyperbaric oxygen treatment and grade 4 ORN necessitating major surgery [14]. Time to event, initial staging, evolution of staging, and treatments for ORN were coded. ORN was the primary stratification variable for this analysis.

Dysphagia measures

Chronic dysphagia present for ≥ 1 year was the primary endpoint measure and was defined in accordance with Caudell et al. (2009) as (1) dependent on a feeding tube; (2) aspiration seen on a modified barium swallow (MBS) or fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallow (FEES); (3) pharyngoesophageal stricture determined by an MBS or endoscopy; or (4) aspiration pneumonia with radiographic evidence of infiltrate [7].

Covariates

Other variables that could influence chronic dysphagia and symptom burden were examined and included demographic variables such as age, sex, race and smoking status, disease variables such as tumor subsite, TNM staging, radiotherapy fractionation schedule, total radiotherapy dose and number of fractions [8]. Type and timing of systemic therapy (induction and/or concurrent chemotherapy or targeted therapy) was also taken into account.

Symptom burden assessment

Symptom burden was assessed via a multi-symptom inventory, the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory – Head and Neck Module (MDASI-HN) among a nested subgroup of patients who completed the inventory after consenting to participation in a prospective survey study. The MDASI-HN is a brief 28-item multi-symptom inventory that measures symptom burden and interference and has been validated using principal axis factoring, demonstrating high levels of reliability for each set of items [17]. There are 13 core items representing general cancer related symptoms and 9 head and neck cancer specific items included in the MDASI-HN which are mouth sores, tasting food, constipation, problems with teeth or gums, skin pain, voice or speech difficulties, choking or coughing, chewing or swallowing problems, and increased mucus secretions [17]. The other 6 items rate interference with activity and daily function. Each item is rated on a numeric scale of 1 to 10, from “not present” for systemic and head and neck symptoms to “as bad as you can imagine” or from “did not interfere” or interfered completely” for interference items. All of the MDASI-HN surveys post-dated ORN events in ORN cases.

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics were calculated. Associations between dysphagia classification and ORN status or grade were examined using bivariate chi-square tests. Mean MDASI-HN summary scores (total symptom burden, local symptom burden, systemic symptom burden, and interference) were computed and compared between groups based on ORN status using two-sample t-tests. A non-Bonferroni corrected p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant for this pilot study. Statistical analyses were performed using the STATA data analysis software, version 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

Participants

The study sample included 349 patients with a median age of 56 years as detailed in Table 1. Median follow-up was 78 months.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| All Patients | Osteoradionecrosis # of pts (ORN rate %) |

p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 313 | 31 (9.9) | 0.763 |

| Female | 36 | 3 (8.3) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 328 | 33 (10.1) | 0.747 |

| Non-White | 21 | 1 (4.8) | |

| Age, y | |||

| ≤56 | |||

| >56 | |||

| Smoking status | |||

| Current | 63 | 9 (14.3) | 0.303 |

| Former | 127 | 13 (10.2) | |

| Never | 159 | 12 (7.6) | |

| T Classification | |||

| 1 | 66 | 4 (6.1) | 0.352 |

| 2 | 162 | 14 (8.6) | |

| 3 | 76 | 11 (14.5) | |

| 4 | 45 | 5 (11.1) | |

| N Classification | |||

| 0 | 19 | 0 | 0.121 |

| 1 | 18 | 2 (11.1) | |

| 2 | 297 | 32 (10.8) | |

| 3 | 15 | 0 | |

| AJCC Staging | |||

| 2 | 3 | 0 | 0.770 |

| 3 | 27 | 2 (7.4) | |

| 4 | 319 | 32 (10.0) | |

| Cancer Subsite | |||

| Base of tongue | 190 | 17 (9.0) | 0.893 |

| Posterior wall or soft palate |

6 | 0 | |

| Tonsil | 153 | 17 (11.1) | |

| Therapeutic Combination | |||

| Induction | 80 | 6 (7.5) | 0.719 |

| Concurrent | 162 | 18 (11.1) | |

| Induction + Concurrent |

102 | 10 (9.8) | |

| Adjuvant | 5 | 0 | |

| IMRT Schedule | |||

| Once daily | 307 | 31 (10.1) | 0.545 |

| Accelerated | 42 | 3 (7.1) | |

| Fractionation | |||

| IMRT Technique | |||

| Split-field | 328 | 31 (9.5) | 0.731 |

| Full field | 21 | 3 (14.3) | |

| Neck Dissection after IMRT | |||

| No | 274 | 28 (10.2) | 0.566 |

| Yes | 75 | 6 (8) | |

| Total | 349 | 34 | |

p-values shown for comparison of clinical and demographics by ORN status

Development of ORN after IMRT

34 patients out of 349 (9.7%, 95% CI: 6.8%–13.3%) developed ORN with a median follow-up of 78 months (minimum follow-up: 12 months; IQR: 60–101 months). Table 1 outlines sex, race, age, smoking status, and disease and treatment characteristics. There were no statistically significant demographic, disease or treatment type predictive of ORN (p>0.05). ORN was more common in patients with greater disease burden, including patients with T3 or T4 primary tumors or node-positive disease, but these differences were not statistically significant. A non-significant positive trend was also observed with smoking status at baseline and development of ORN (Wilcoxon non-parametric p for trend=0.126).

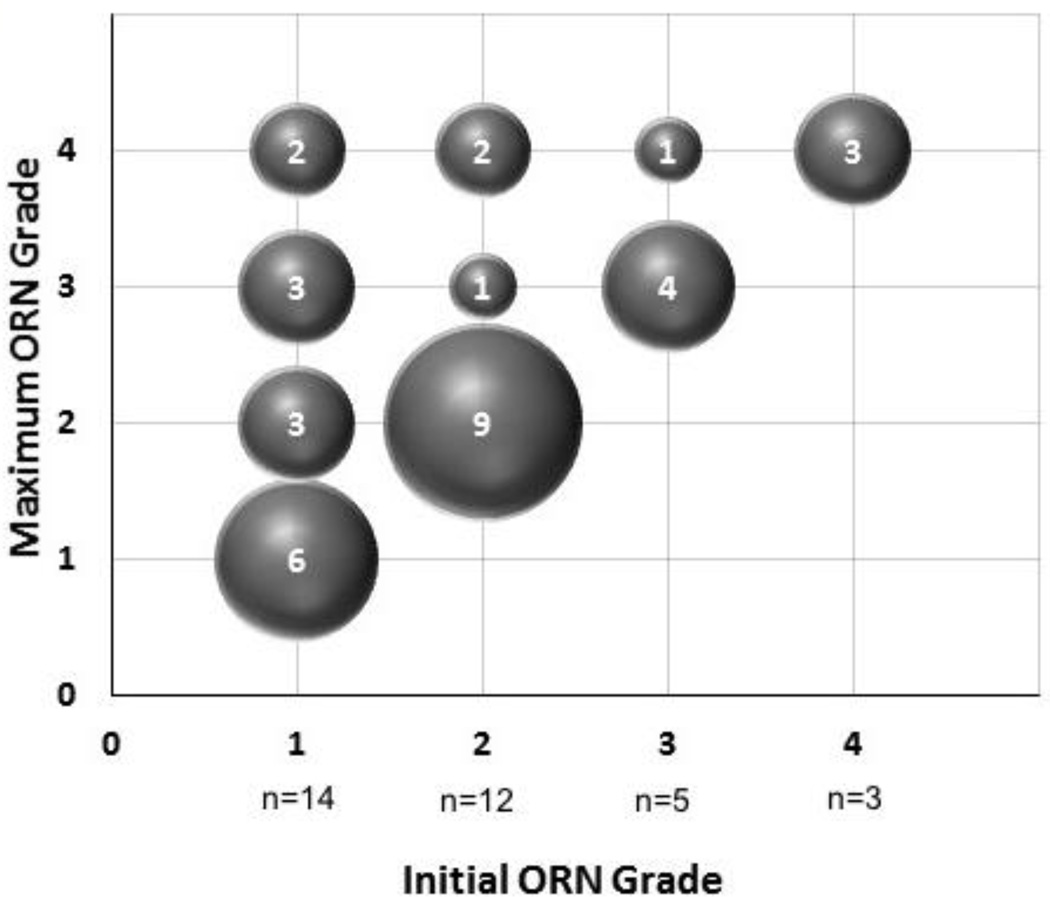

Initial and maximum grades of ORN are summarized in Figure 1, depicting evolution of ORN grading. Overall, 35% (12/34) of ORN cases progressed after initial diagnosis. A total of 8 patients (23.5%) had grade 4 ORN necessitating major surgery; 6 of 8 ultimately underwent mandibulectomy (2 marginal, 4 segmental) while 2 refused surgery.

Figure 1. Progression of Osteoradionecrosis.

n = 34 ORN cases

Numbers inside the bubbles denote number of patients with ORN

ORN and chronic dysphagia

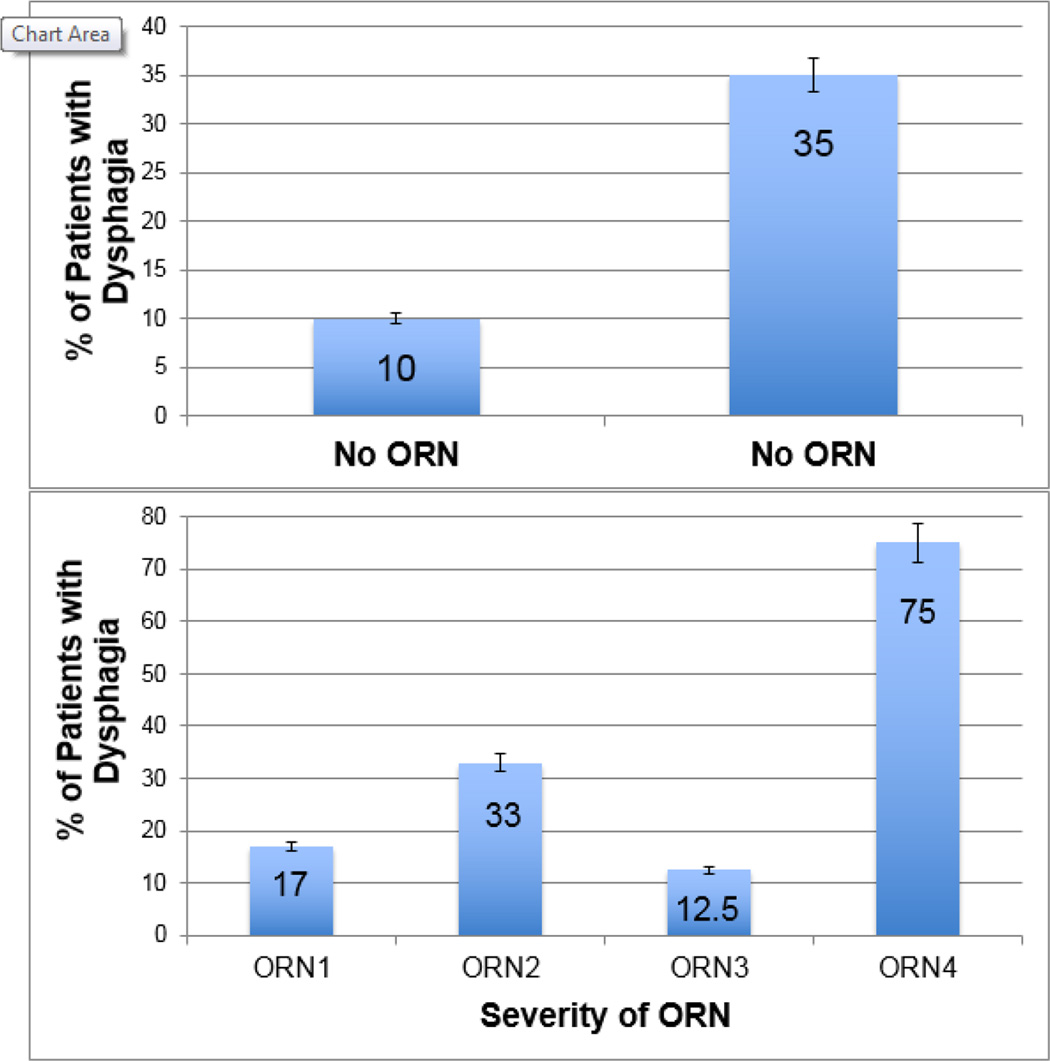

Of the 34 patients with ORN, 12 (35%, 95% CI: 19.7–53.5%) had chronic dysphagia. Significantly fewer of the patients without ORN developed dysphagia (33/315, 11%, 95% CI: 7.3–14.4%, p<0.001). Patients who developed ORN were 4.7 times more likely to have chronic dysphagia relative to patients without ORN (OR: 4.7, 95% CI: 2.1–10.3) as shown in Figure 2. ORN grade was also significantly associated with the prevalence of chronic dysphagia (p<0.001). The majority of patients with grade 4 ORN (6 patients, 75%) had chronic dysphagia, 5 of these 6 patients underwent mandibulectomy reconstructed with vascularized free flaps. Details of ORN stage and treatment are outlined in Table 1.

Figure 2. Prevalence of Chronic Dysphagia by Osteoradionecrosis Status.

n = 349 OPC survivors

Chronic dysphagia was significantly more common in patients who developed ORN (OR: 4.7. 95% CI: 2.1–10.3, p<0.001), illustrated in the top panel. Prevalence of dysphagia significantly differed by ORN grade (p<0.001), depicted in the bottom panel.

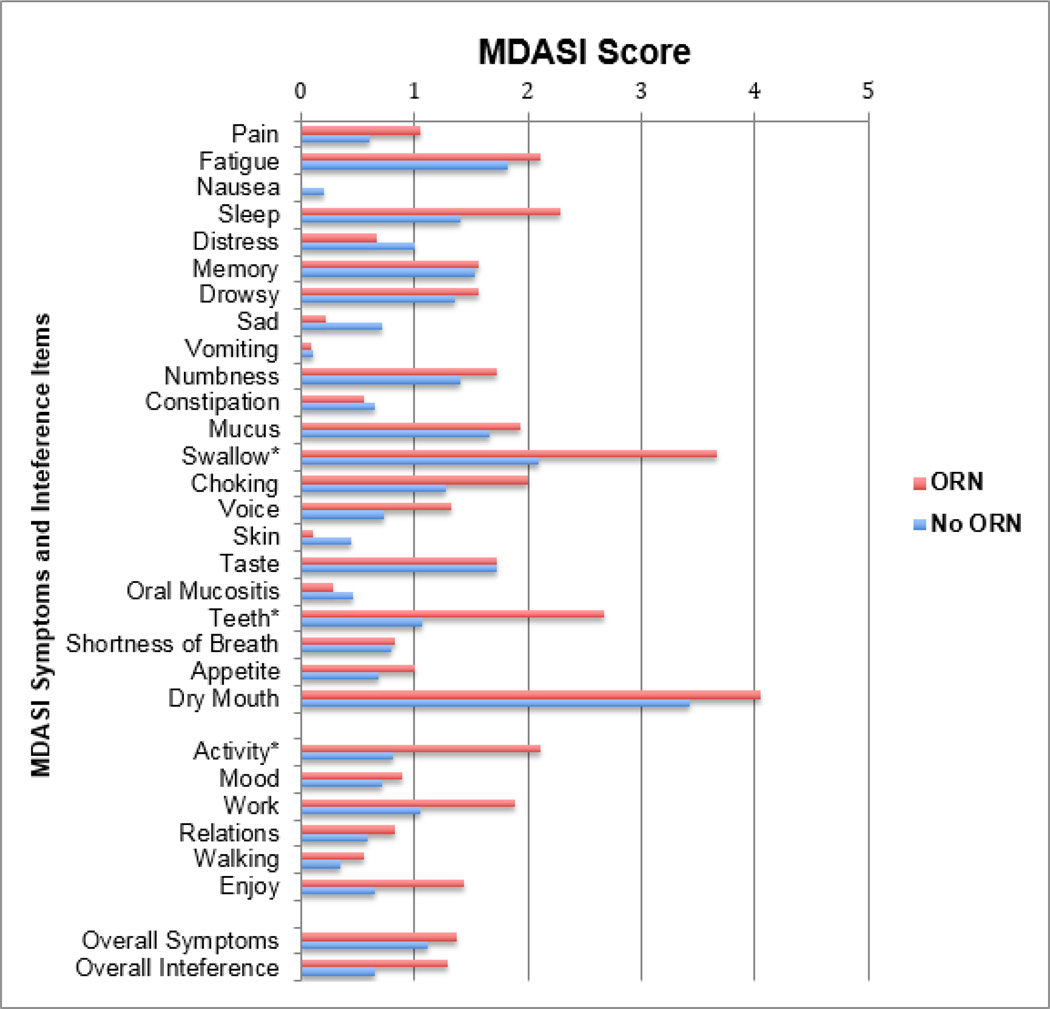

Osteoradionecrosis and systemic and local symptoms

MDAI-HN scores from the ORN and no ORN groups are shown in Figure 3 for a nested subgroup of 118 patients who participated in a cross-sectional MDASI-HN survey. Demographics, tumor burden and treatment type did not significantly differ in the subgroup of survey responders from the remainder of the cohort (p>0.10). Summary MDASI-HN scores, including overall symptom burden (No ORN: 1.1±0.1 vs. ORN: 1.4±0.4, p=0.464), systemic symptom burden (No ORN: 1.0±0.1 vs. ORN: 1.1±0.3, p=0.814), local symptom burden (No ORN: 1.3±0.1 vs. ORN: 1.8±0.4, p=0.177), and overall interference (No ORN: 0.7±0.1 vs. ORN: 1.3±0.4, p=0.082) did not statistically differ between ORN and no ORN groups. Examining single items, a significant association was found with local symptoms of swallowing (“your difficulty swallowing or chewing”, No ORN: 2.1±0.2 vs. ORN: 3.6±0.8, p=0.033) and teeth and/or gum problems (“your problems with your teeth or gums”, No ORN: 1.1±0.2 vs. ORN: 2.7±0.9, p=0.016), as well as with the interference item change in activity (“how much have symptoms interfered with general activity”, No ORN: 0.8±0.2 vs. ORN: 2.1±0.7, p=0.015).

Figure 3. MDASI-HN Scores by ORN Status.

n = 118 OPC survivors (survey responders)

Mean MDASI-HN scores plotted, *p<0.05

Discussion

ORN and dysphagia are two potentially severe late complications of radiation therapy for OPC. The reported incidence of ORN following head and neck radiation is 6.4%, and clinically detectable chronic dysphagia is estimated to occur in at least 12% to 38.5% of survivors [6,7,11, 13]. The occurrence of ORN and dysphagia following head and neck radiation therapy are both extensively studied in the literature, but no study to date has examined the association between these two complications. Results from this retrospective study of long-term OPC survivors treated with combined modality intensity-modulated radiotherapy regimens demonstrate that ORN is associated with a significantly higher prevalence of chronic dysphagia detected by clinical events (OR: 4.6, 95% CI: 2.1–10.3) and also as assessed by a patient-reported outcome instrument (MDASI-HN).

Previous studies have addressed the association of different mandibular dose-volume correlates and various permutations of maximum and mean dose with ORN development, but in part because of the relatively low incidence of ORN, it remains unclear what dose-volume parameters are most significantly associated with this detrimental complication of radiation therapy [13–15]. In a case-control analysis including patients from this cohort, dose-volume histogram (DVH) comparison found that mandibular mean dose was significantly higher in the ORN cases (48.1 vs 43.6 Gy) while the maximum dose was not significantly different [18].

Chronic dysphagia in OPC survivors is most likely when radiation doses exceed 50-Gy to the pharyngeal axis, which all patients in this study received [6]. Structures of the oral cavity and oropharynx can also be compromised by development of ORN, particularly high-grade ORN necessitating surgical management, providing an explanation for the frequent occurrence of dysphagia among patients with grade 4 ORN in this cohort. Five of the 6 patients who underwent mandibulectomy and reconstruction with vascularized free flaps in this study had chronic dysphagia, which first developed or was detected clinically prior to surgical reconstruction. The goals of reconstruction are to restore continuity and projection of the mandible, to restore dead space in the oral cavity, to provide a scaffolding onto which an occlusion or bite can be created, and to restore missing soft tissues that may facilitate transit in the oral phase of swallowing and to restore oral competence [19]. Achievement of all these goals is very difficult and surgery itself may create new complications. Alam et al. (2009) observed development of aspiration pneumonia in 4/33 (12%) of patients following vascularized free flap reconstruction in patients with advanced mandibular ORN which was thought to be related to edema and poor sensation in the hypopharynx [20]. Chandarana et al. (2012) followed 8 of 12 (73%) patients with advanced ORN treated with mandibulectomy and osteocutaneous free flap reconstruction and found that after 1 year, 7 patients who completed a speech and swallowing questionnaire-based outcome instrument reported a normal oral diet with only 3 of the 7 requiring oral supplementation [19]. Comparatively higher rates of dysphagia observed in our study among patients with grade 4 ORN necessitating major surgery may be due to the oropharyngeal site of the primary tumor requiring high therapeutic doses of radiotherapy to a swallowing critical zone. Other studies analyzed outcomes from patients with mixed primary sites [19,20].

Use of different grading scales for ORN also affects definitions of severity. In this study, ORN was graded on a 4-point scale as defined by Tsai et al. (2013) [14]. The advantage of this scale is that it reliably assigns a grade from a retrospective chart review based on clinical management of the ORN; however, it does not consider subjective symptoms the patient experiences related to ORN. It is possible that patients were downgraded in diagnosis of severity of ORN relative to other grading methodologies. The Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0 grading system for ORN was initially considered as it takes into account patient symptoms as a marker of severity of ORN, but definitions for each grade were difficult to apply retrospectively as not all symptoms were detailed in the patient charts[21]. There is a need for development and validation of a uniform classification scheme for ORN.

Systemic symptoms caused by ORN are varied depending on the grade or extent of the lesion. Associated symptoms may include pain, swelling, ulcers, trismus, development of an extraoral fistula, or jaw fracture. Among 4 studies examining patient-reported outcomes in patients with ORN, the most commonly used patient-reported outcome (PRO) measure used in patients with ORN in the literature is the University of Washington Quality of Life scale (UW-QOL) that quantifies 12 symptom domains on a 4-point scale [22–25]. Using UW-QOL, patients with ORN of any stage tended to report more problems with pain, appearance, activity, recreation, and swallowing and chewing [25]. Similarly, Chang et al. (2012) used the UW-QOL questionnaire to survey patients with grade 4 ORN requiring surgery and reconstruction and found that patients’ greatest concerns were swallowing, chewing and appearance [23]. In our study, using the MDASI-HN as a PRO measure of symptom burden, we similarly found elevated symptom burden for problems with swallowing, teeth and gums, and associated activity inference in patients with ORN. The symptom burden data we report are limited by a cross-sectional, single time point in a nested subgroup of survey responders. Future studies are needed to provide longitudinal survey data systematically in all patients detailing evolution of symptoms in relationship to ORN and other toxicities. Other patient comorbidities were not included in this study but may be worth future investigation to evaluate their influence on symptom burden.

Conclusions

Osteoradionecrosis (ORN) is a potential late complication of radiation therapy that can progress to a debilitating disease with related pain, disfigurement and functional impairment. This study found that ORN is associated with excess burden of chronic dysphagia, another late complication of radiation therapy. 35% (12/34) of patients with ORN had chronic dysphagia compared to 11% (33/315) of patients without ORN. Patients with ORN tended to experience greater problems with swallowing, teeth and gums and interference in normal activities. As expected, chronic dysphagia was also most common in patients with high grade ORN, which may be related not only to biologic predisposition to late effects but also to the treatment of ORN itself, particularly in those with grade 4 ORN requiring major surgery. Future studies in patients treated for advanced ORN should investigate the relationship of symptom burden and associated toxicities with the extent of treatment using more defined and validated grading schemas to determine whether goals of reconstruction were achieved.

Highlights.

A retrospective study examining the relationship between mandibular osteoradionecrosis (ORN) and chronic dysphagia

The patient population consists of long-term oropharynx cancer survivors treated with bilateral IMRT and systemic therapy

Higher prevalence of chronic dysphagia was reported in patients with ORN compared to patients without ORN

High-grade ORN is significantly associated with prevalence of dysphagia

There is higher symptom burden among patients with ORN, as measured using a patient-reported outcomes instrument, the MDASI-HN

Acknowledgments

The research was accomplished under the auspices of the multidisciplinary Oropharynx Program, and funded in part through infrastructure support of the Stiefel Oropharyngeal Research Fund of the Charles and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Daneen Stiefel Center for Head and Neck Cancer. Drs. Lai, Hutcheson, Chambers, Mohamed and Fuller received funding support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (1R01DE025248-01/R56DE025248-01). Dr. Hutcheson received grant and/or salary support from NIH/National Cancer Institute (NCI) (5R03CA188162-01) and the MD Anderson Institutional Research Grant (IRG) Program. Dr. Fuller received grant and/or salary support from the NIH/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Head and Neck Specialized Programs of Research Excellence (SPORE) Developmental Research Program Award (P50CA097007-10) and Paul Calabresi Clinical Oncology Program Award (K12 CA088084-06); a National Science Foundation (NSF), Division of Mathematical Sciences, Joint NIH/NSF Initiative on Quantitative Approaches to Biomedical Big Data (QuBBD) Grant (NSF 1557679); a General Electric Healthcare/MD Anderson Center for Advanced Biomedical Imaging In-Kind Award; an Elekta AB/MD Anderson Department of Radiation Oncology Seed Grant; the Center for Radiation Oncology Research (CROR) at MD Anderson Cancer Center; and the MD Anderson Institutional Research Grant (IRG) Program. Dr. Fuller has received speaker travel funding from Elekta AB. Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Cancer Center Support (Core) Grant CA016672 to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner L, Mupparapu M, Akintoye SO. Review of the complications associated with treatment of oropharyngeal cancer: a guide for the dental practitioner. Quintessence Int. 2013;44:267–279. doi: 10.3290/j.qi.a29050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pezzuto F, Buonaguro L, Caponigro F, Ionna F, Starita N, Annunziata C, et al. Update on head and neck cancer: current knowledge on epidemiology, risk factors, molecular features and novel therapies. Oncology. 2015;89:125–136. doi: 10.1159/000381717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pytynia KB, Dahlstrom KR, Sturgis EM. Epidemiology of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:380–386. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simard EP, Torre LA, Jemal A. International trends in head and neck cancer incidence rates: differences by country, sex and anatomic site. Oral Oncol. 2014;50:387–403. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Hu C, Eisbruch A. Organ-sparing radiation therapy for head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:639–648. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caudell JJ, Schaner PE, Meredith RF, Locher JL, Nabell LM, Carroll WR, et al. Factors associated with long-term dysphagia after definitive radiotherapy for locally advanced head-and-neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;73:410–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutcheson KA, Abualsamh AR, Sosa A, Weber RS, Beadle BM, Sturgis EM, et al. Impact of selective neck dissection on chronic dysphagia after chemo-intensity-modulated radiotherapy for oropharyngeal carcinoma. Head Neck. 2015;38:886–893. doi: 10.1002/hed.24195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisbruch A, Levendag PC, Feng FY, Teguh D, Lyden T, Schmitz PIM, et al. Can IMRT or brachytherapy reduce dysphagia associated with chemoradiotherapy of head and neck cancer? The Michigan and Rotterdam experiences. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2007;69:S40–S42. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.04.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starmer HM, Tippett D, Webster K, Quon H, Jones B, Hardy S, et al. Swallowing outcomes in patients with oropharyngeal cancer undergoing organ-preservation treatment. Head Neck. 2014;36:1392–1397. doi: 10.1002/hed.23465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutcheson KA, Lewin JS, Barringer DA, Lisec A, Gunn GB, Moore MWS, et al. Late dysphagia after radiotherapy-based treatment of head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:5793–5799. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lyons A, Osher J, Warner E, Kumar R, Brennan PA. Osteoradionecrosis--a review of current concepts in defining the extent of the disease and a new classification proposal. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014;52:392–395. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Felice F, Thomas C, Patel V, Connor S, Michaelidou A, Sproat C, et al. Osteoradionecrosis following treatment for head and neck cancer and the effect of radiotherapy dosimetry: the Guy“s and St Thomas” Head and Neck Cancer Unit experience. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.oooo.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsai CJ, Hofstede TM, Sturgis EM, Garden AS, Lindberg ME, Wei Q, et al. Osteoradionecrosis and radiation dose to the mandible in patients with oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee IJ, Koom WS, Lee CG, Kim YB, Yoo SW, Keum KC, et al. Risk factors and dose-effect relationship for mandibular osteoradionecrosis in oral and oropharyngeal cancer patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:1084–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shan X-F, Li R-H, Lu X-G, Cai Z-G, Zhang J, Zhang J-G. Fibular free flap reconstruction for the management of advanced bilateral mandibular osteoradionecrosis. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:e172–e175. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000001391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenthal DI, Mendoza TR, Chambers MS, Asper JA, Gning I, Kies MS, et al. Measuring head and neck cancer symptom burden: the development and validation of the M. D. Anderson symptom inventory, head and neck module. Head Neck. 2007;29:923–931. doi: 10.1002/hed.20602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohamed AS, Lai SY, Murri M, Hutcheson KA, Sandulache VC, Hobbs B, et al. Dose-volume correlates of osteoradionecrosis of the mandible in oropharynx patients receiving intensity modulated radiation therapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;96:S220–S221. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chandarana S, Chanowski E, Casper K, Wolf G, Bradford C, Worden F, et al. Osteocutaneous free tissue transplantation for mandibular osteoradionecrosis. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2012;29:005–014. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alam DS, Nuara M, Christian J. Analysis of outcomes of vascularized flap reconstruction in patients with advanced mandibular osteoradionecrosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Department of Health and Human Services National Cancer Institute. [accessed August 1, 2016];Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.0. HttpevsNciNihgovftpCTCAECTCAE--QuickReferencexPdf 2009. http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf.

- 22.Jacobson AS, Zevallos J, Smith M, Lazarus CL, Husaini H, Okay D, et al. Quality of life after management of advanced osteoradionecrosis of the mandible. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;42:1121–1128. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang EI, Leon P, Hoffman WY, Schmidt BL. Quality of life for patients requiring surgical resection and reconstruction for mandibular osteoradionecrosis: 10-year experience at the University of California San Francisco. Head Neck. 2012;34:207–212. doi: 10.1002/hed.21715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mücke T, Koschinski J, Wolff K-D, Kanatas A, Mitchell DA, Loeffelbein DJ, et al. Quality of life after different oncologic interventions in head and neck cancer patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2015;43:1895–1898. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers SN, D'Souza JJ, Lowe D, Kanatas A. Longitudinal evaluation of health-related quality of life after osteoradionecrosis of the mandible. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;53:854–857. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]