Abstract

The ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-like (Nedd4L, or Nedd4-2) binds to and regulates stability of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) in salt-absorbing epithelia in the kidney, lung, and other tissues. Its role in the distal colon, which also absorbs salt and fluid and expresses ENaC, is unknown. Using a conditional knock-out approach to knock out Nedd4L in mice intestinal epithelium (Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2) we show here that Nedd4L depletion leads to a higher steady-state short circuit current (Isc) in mouse distal colon tissue relative to controls. This higher Isc was partially reduced by the addition of apical amiloride and strongly reduced by basolateral bumetanide as well as by depletion of basolateral Cl−, suggesting that Na+/K+/2Cl− (NKCC1/SLC12A2) co-transporter and ENaC are targets of Nedd4L in the colon. In accordance, NKCC1 (and γENaC) protein abundance in the colon of the Nedd4L knock-out animals was increased, indicating that Nedd4L normally suppresses these proteins. However, we did not observe co-immunoprecipitation between Nedd4L and NKCC1, suggesting that Nedd4L indirectly suppresses NKCC1 expression. Low salt diet resulted in a strong increase in β and γ (but not α) ENaC mRNA and protein expression and ENaC activity. Although salt restriction also increased NKCC1 protein and mRNA abundance, it did not lead to its elevated activity (Isc). These results identify NKCC1 as a novel target for Nedd4L-mediated down-regulation in vivo, which modulates ion and fluid transport in the distal colon together with ENaC.

Keywords: cell biology, E3 ubiquitin ligase, epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), gene knockout, intestine, membrane transport, ubiquitin

Introduction

Members of the neuronal precursor cell expressed developmentally downregulated 4 (Nedd4)2 family of E3 ubiquitin ligases typically comprise a C2-WW(n)-HECT domain architecture and encompass nine mammalian proteins, including Nedd4-like (Nedd4L/Nedd4-2) (1, 2). Nedd4L is best known for its role in regulating cell surface stability of the epithelial Na+ Chanel (ENaC) (3–5). ENaC is expressed in salt-absorbing epithelia in the distal nephron, lung, distal colon, and other tissues (6, 7), where it promotes salt and fluid absorption, hence playing a pivotal role in regulating blood volume and pressure (8). ENaC is composed of three subunits (αβγ) (9), each containing a short cytosolic PY motifs (PPXY) that bind the WW domains of Nedd4L (1, 3, 10, 11), leading to ubiquitination, endocytosis, and lysosomal degradation of ENaC (12). Mutations in the PY motif of β or γ ENaC, which prevent it from properly binding to Nedd4L, cause Liddle syndrome, a hereditary hypertension caused by increased cells surface stability and activity of ENaC in the kidney (13, 14). In accordance, knock-out of Nedd4L in mice led to a salt-induced hypertension (15). In response to aldosterone, SGK1 phosphorylates Nedd4L (16), resulting in binding of 14-3-3 to the phosphorylated Nedd4L and its reduced ability to bind ENaC and suppress it (17). This leads to enhanced ENaC stability and function.

More recently a kidney-specific knock-out of Nedd4L identified NCC (SLAC12A3) as an additional target for Nedd4L in the kidney (18, 19); this knock-out led to stabilization of NCC (and ENaC), hypertension, and metabolic acidosis, partially resembling PHAII-like disease (19).

In addition to its regulation of ENaC in the kidney, Nedd4L was also shown to play a critical role in lung fluid absorption via controlling cell surface stability of ENaC knock-out of Nedd4L in lung epithelia caused death due to elevated ENaC activity, lung dehydration, massive lung inflammation, and airway mucus plugging (20, 21), thus resembling cystic fibrosis-like lung disease. These adverse effects were rescued with the ENaC inhibitor amiloride (20).

The role of Nedd4L in the distal colon, a tissue known to absorb fluid and express ENaC (6, 7), is unknown. Here we generated intestinal epithelial-specific knock-out of Nedd4L and identify the Na+/K+/2Cl− co-transporter, NKCC1, as a major target of Nedd4L in the distal colon, where it regulates salt transport along with ENaC.

Results

Nedd4L Regulates Function of NKCC1 and ENaC in the Colon

Nedd4L is expressed in the distal colon (Fig. 1A), a tissue also known to express ENaC (Refs. 7 and 22 and see below). To study the physiological function of Nedd4L in the colon, we generated an inducible intestine-specific Nedd4L conditional knock-out mouse in the intestine by crossing Nedd4L floxed mice to Vil-CreERT2 mice (Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2), in which Nedd4L is deleted in the intestine upon treatment with tamoxifen (Tam) (Fig. 1A). A second line was generated by crossing Nedd4Lf/f mice to a Vil-Cre line (Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-Cre), where Nedd4L is constitutively deleted in the intestine (Fig. 1A). Knock-out mice (without or with tamoxifen induction) were viable, fertile, weighed normally, appeared overall normal, and had an apparent normal gut morphology (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Higher Isc in distal colons of tamoxifen-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice is caused by increased NKCC1 and ENaC function. A, loss of Nedd4L in Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-Cre and in Tam-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 distal colonic epithelial cells relative to WT and un-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice. Positive control: lysate from V5-Nedd4L transfected into Hek293T cells. B, Nedd4L knock-out in the distal colons of tamoxifen-treated Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice leads to elevated Isc compared with Nedd4Lf/f or un-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice (hereafter called Controls; see the inset). The elevated Isc is sensitive to apically added ENaC inhibitor, amiloride (10 μm) or basolaterally added NKCC inhibitor bumetanide (200 μm). Arrowheads indicate the time of drug addition. C, basolateral Cl− depletion abolishes Isc; Cl− was depleted from the media by substituting NaCl with equimolar sodium glutamate at the indicated times (arrowhead). Bumetanide addition (200 μm, basolateral side) in the Cl−-depleted media had no further effect. D, quantitative comparison of resting (steady state), amiloride-sensitive, and bumetanide-sensitive Isc in distal colonic segments from Tam-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice and controls. Control mice included Nedd4Lf/f and un-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice. Data are the mean ± S.E. of the indicated (in parentheses) number of mice/colons. p values are shown in each panel. E, as in D except Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-Cre mice were used for the experiments (instead of Tam-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice).

To study the effect of loss of Nedd4L in the colon on ENaC function, we measured short circuit current (Isc) in colonic segments prepared from tamoxifen-induced or uninduced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice using Ussing chambers in the absence/presence of amiloride. As seen in Fig. 1, B and D and Fig. 1B, inset, the resting Isc was significantly higher in distal colon segments of Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice relative to the Nedd4f/f mice or relative to uninduced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2mice. Curiously, this difference was not seen in proximal colonic segments (not shown) where ENaC is not expressed (6). The addition of amiloride (10 μm) to the apical (luminal) side of the distal colon segments led to a small decrease in Isc, suggesting that ENaC is only partially responsible for the elevated Isc in the induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice (Fig. 1, B and D).

Because amiloride was not sufficient to eliminate the difference in Isc between the colons of induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice versus controls, we tested the possibility that basolateral NKCC1 (known to be expresses in the colon) may be involved as well. Thus, we treated colonic segments of induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice or of controls with apical amiloride (as above) followed by basolateral addition of the NKCC1 inhibitor bumetanide (200 μm). This maneuver led to the abolishment of the difference in Isc between the Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2mice and controls (Fig. 1, B and D). In accordance, Cl− depletion from the media had the same effect (Fig. 1C). Similar results were also obtained with Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-Cre mice in which Nedd4L was constitutively deleted (Fig. 1E). Apical addition of the CFTR inhibitors 172 (25 μm), GlyH101 (25 μm), or glibenclamide (100 μm) to unstimulated or forskolin/isobutylmethylxanthine/genistein (CFTR activators)-stimulated preparations or the Cl− channel inhibitor DNDS (4,4′-dinitro-stilbene-2,2′-disulfonic acid, 250 μm) had a minimal effect on reducing Isc (not shown). However, although forskolin/isobutylmethylxanthine/genistein treatment caused a large increase in Isc, suggestive of CFTR activation, we cannot definitively conclude that CFTR activity was responsible for the Cl− secretion because the currently available CFTR inhibitors are not very effective in the colon.

Nedd4L Regulates Levels of NKCC1 in the Colon but Does Not Bind It

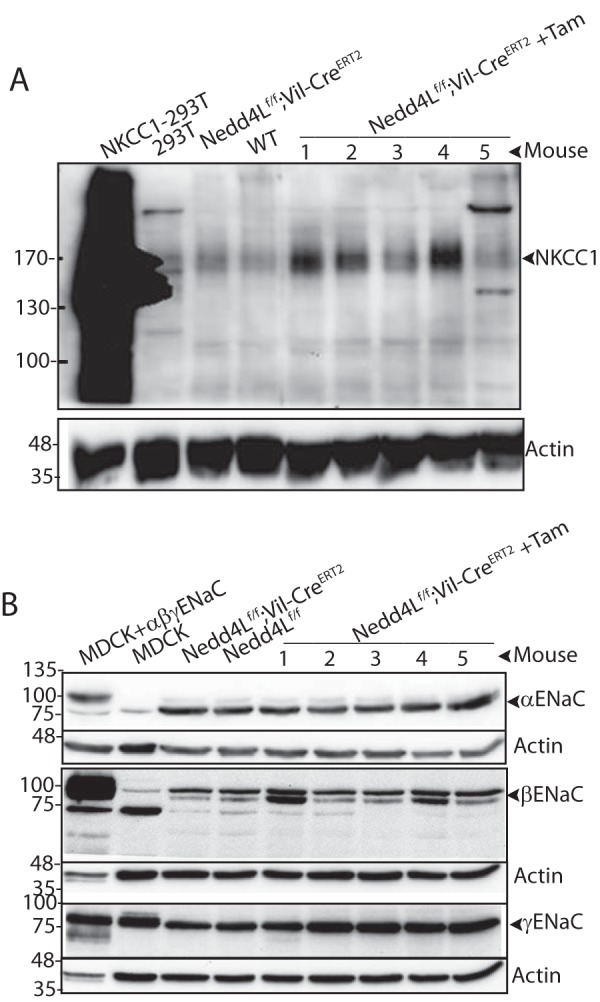

Although it is well established that Nedd4L can directly bind ENaC and regulate its stability (1, 3), how Nedd4L may regulate NKCC1 function is unknown. To address this, and given that Nedd4L is a ubiquitin ligase, we first measured levels of the NKCC1 protein in colonic segments of Tam-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice and controls. Fig. 2A and Fig. 3 show that in several mice/cohorts tested, levels of NKCC1 were increased in the induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice relative to controls, suggesting that Nedd4L normally reduces expression/abundance of NKCC1 in the colon. Interestingly, under the same conditions we observed only a small increase in the abundance of (uncleaved) γENaC, but not αENaC or βENaC, in the Nedd4L knock-out colons relative to controls (Fig. 2B and Fig. 4). This suggests that NKCC1 may be a more important target for Nedd4L in the distal colon under normal diet.

FIGURE 2.

Increased protein levels of NKCC1 in distal colons upon loss of Nedd4L. A, increased expression of NKCC1 in tamoxifen induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mouse distal colon epithelial cells compared with un-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 and Nedd4Lf/f control epithelial cells, analyzed by immunoblotting. Numbers indicate the colons from different mice. Positive control: HA-NKCC1 overexpressed in Hek293T cells. Lysates are from the same five mice shown in Fig. 1A, where loss of Nedd4L is depicted. B, lack of elevated expression of αENaC and βENaC and mild increase in levels of uncleaved γENaC upon loss of Nedd4L in mouse distal colon epithelial cells compared with controls. The analysis was done as above on the same five mice/lysates described in panel A.

FIGURE 3.

Elevated NKCC1 mRNA and protein expression in colons of mice fed a low salt diet. A, expression of NKCC1 in tamoxifen induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mouse distal colon epithelial cells compared with uninduced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 and Nedd4Lf/f control epithelial cells following (or not) a low salt diet, analyzed by WB. Lysate from Hek293T cells overexpressing NKCC1 is included as a positive control, and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (expressing ENaC) as a negative control. B and C, quantification of mRNA (B) and protein (C) expression of NKCC1 in distal colon epithelia of control or tamoxifen-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice in the presence/absence of low salt diet. Data are the mean ± S.E. of the indicated number (N) or mice (in parentheses). p values are indicated only when differences are statistically significant (p < 0.05, unpaired Student's t test).

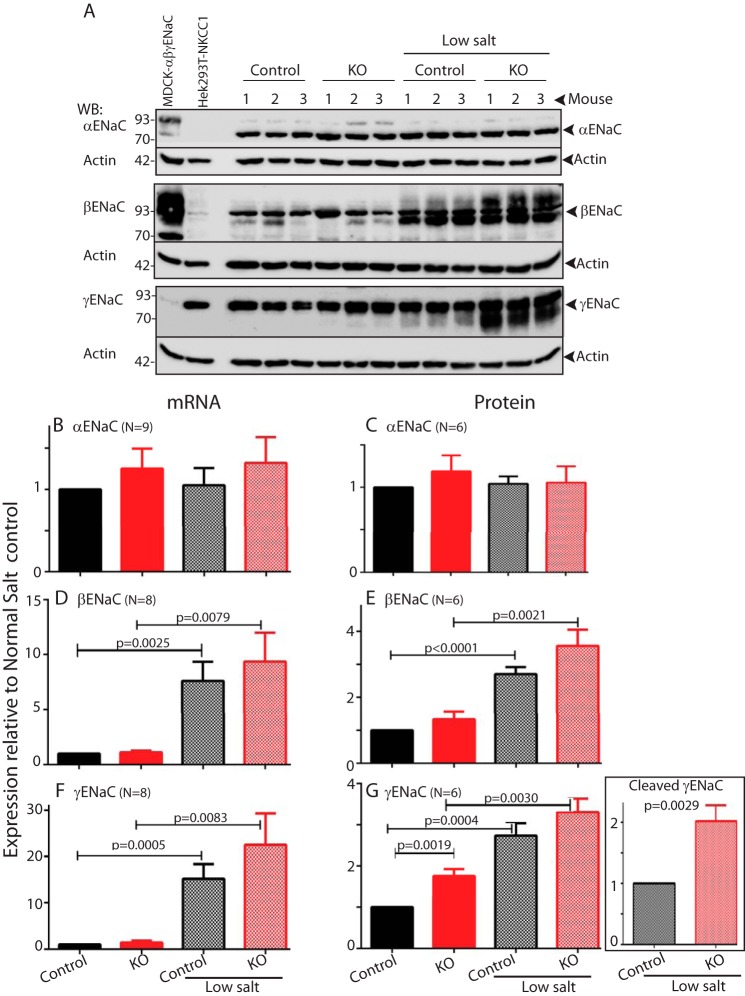

FIGURE 4.

Elevated colonic β or γ (but not α) ENaC mRNA and protein expression under a low salt diet. A, expression of αβγENaC in tamoxifen induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mouse distal colon epithelial cells compared with un-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 and Nedd4Lf/f control epithelial cells following (or not) a low salt diet, analyzed by WB. Lysate from Hek293T cells overexpressing NKCC1 is included as a negative control, and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells overexpressing αβγENaC is a positive control. B–G, quantification of mRNA (B, D, and F) and protein (C, E, G) expression of αENaC (B and C), βENaC (D and E), and γENaC (F and G) in distal colon epithelia of control or tamoxifen-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice in the presence/absence of low salt diet. G, inset/boxed panel depicts protein expression of cleaved γENaC. Data are the mean ± S.E. of the indicated number (N) or mice (in parentheses). p values are indicated only when differences are statistically significant (p < 0.05, unpaired Student's t test).

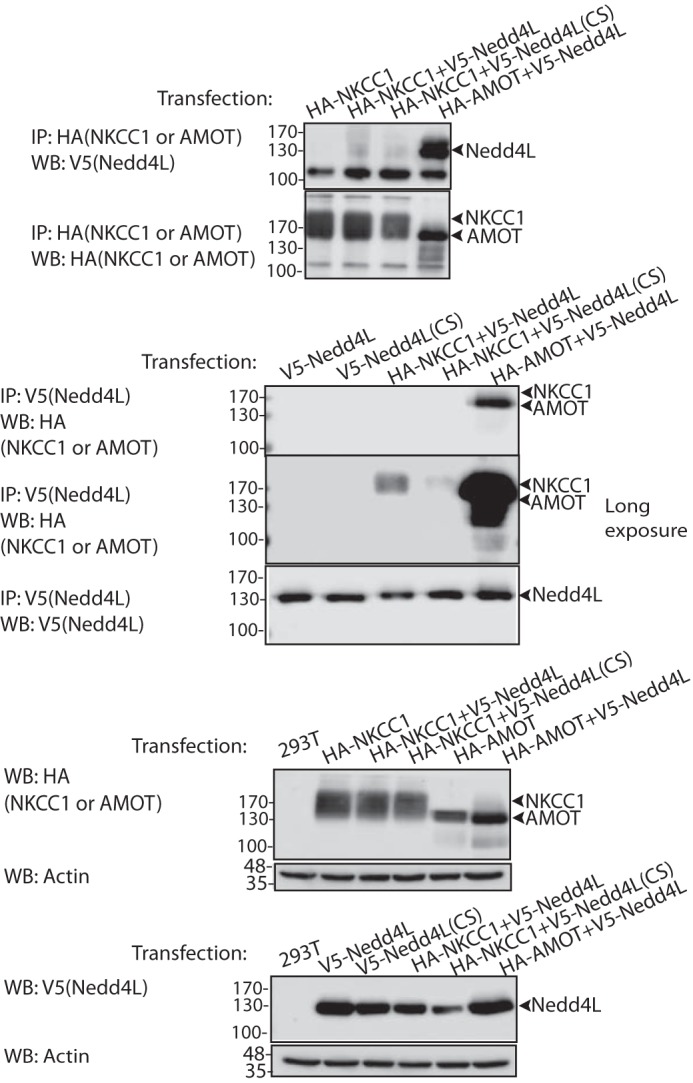

Unlike ENaC, NKCC1 does not possess a PY motif(s) that can bind Nedd4L-WW domains. Nonetheless, in view of the elevated expression of NKCC1 in the Nedd4L knock-out colons, we tested complex formation between Nedd4L and NKCC1. First, we analyzed their co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) in colonic epithelia harvested from WT mice but could not detect any interaction (not shown). To ensure that this lack of binding is not due to low abundance of the endogenous proteins (or low affinity of the antibodies to the endogenous proteins), we overexpressed tagged NKCC1 and Nedd4L in Hek293T cells and repeated the co-IP experiments. Our results demonstrated poor or no interactions between these proteins (Fig. 5), suggesting that Nedd4L does not directly bind NKCC1 or that binding (direct or indirect) is very weak. In support, we could not detect Nedd4L-mediated ubiquitination of NKCC1 when expressed in Hek293T cells. RT-PCR analysis showed an increase in mRNA abundance of NKCC1, which paralleled that of protein abundance (Fig. 3, B and C), suggesting the possibility that Nedd4L indirectly suppresses expression of NKCC1 in the colon, at least in part by regulating mRNA expression. mRNA abundance of all three ENaC subunits was not altered by colonic depletion of Nedd4L (Fig. 4, B, D, and F).

FIGURE 5.

Lack of binding between Nedd4L and NKCC1. Lysates from Hek293T co-expressing HA-NKCC1 and V5-Nedd4L were used to immunoprecipitate (IP) HA-NKKC1 and immunoblot (WB) V5-Nedd4L (upper panel) or, reciprocally, to immunoprecipitate V5-Nedd4L and immunoblot NKCC1 (short and long exposures). Positive control: co-IP of HA-AMOT (angiomotin) and V5-Nedd4L. The lowest two panels depict lysate controls. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results.

Salt Restriction Enhances βγENaC and NKCC1 Expression and ENaC Function in the Colon

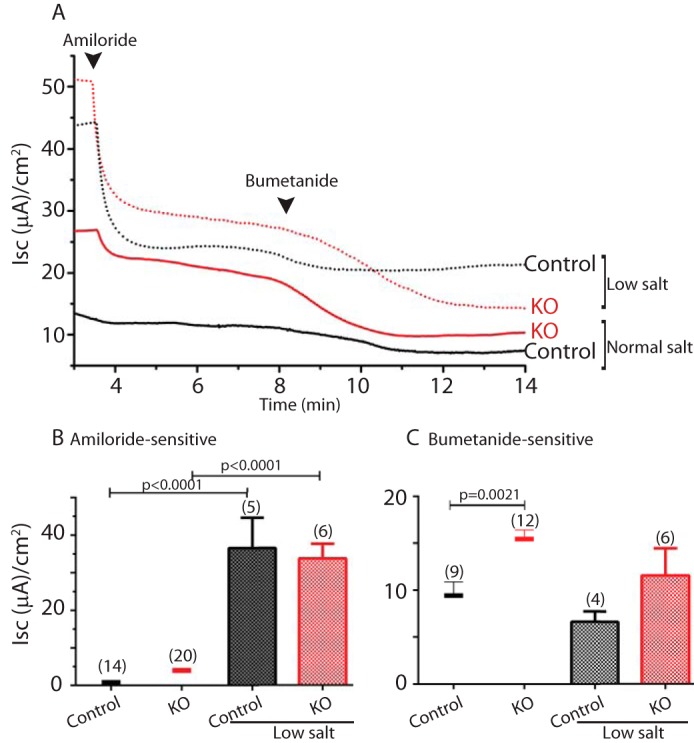

Low salt diet is well known to increase ENaC expression (23, 24). In accordance, our results show a greatly elevated Isc in the colons of the low salt-fed mice relative to those fed anormal diet (Fig. 6A). This increase was strongly inhibited by amiloride (Fig. 6B), indicating that it was largely mediated by ENaC. Under a low salt diet, Nedd4L depletion did not further increase ENaC activity (Fig. 6B). Moreover, a low salt diet reduced NKCC1-mediated Isc relative to a normal diet, but this Isc was still dependent on Nedd4L (Fig. 6C). Together, these results suggest that under a normal diet in the colon, Nedd4L regulates the function of NKCC1 and to a lesser extent, ENaC, but that low salt diet greatly increases colonic ENaC function, independent of Nedd4L.

FIGURE 6.

Increased amiloride-sensitive (ENaC) Isc, but not bumetanide-sensitive (NKCC1) Isc, by salt restriction. A, Nedd4L knock-out (KO) in the distal colon of tamoxifen-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice led to elevated Isc compared with Nedd4Lf/f or uninduced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 control mice, which was further increased under low salt diet. This increased Isc was sensitive to apically added ENaC inhibitor, amiloride (10 μm) but not basolaterally added NKCC1 inhibitor bumetanide (200 μm). Arrowheads indicate the time of drug addition. B and C, quantification of the low salt diet effect in the experiment described in A, performed with the indicated (in parentheses) number of mice for each genotype, analyzing ENaC (amiloride-sensitive) (B) and NKCC1 (bumetanide-sensitive) (C) Isc. Values in normal salt diet, reproduced from Fig. 1D, are depicted here as bars for comparison with the low salt diet values. Data are the mean ± S.E. of the indicated number of mice (in parentheses). p values are indicated only when differences are statistically significant (p < 0.05, unpaired Student's t test).

Under a low salt diet, mRNA and protein expression of β and γ ENaC (but not αENaC) as well as NKCC1 were increased relative to the colons of normal-diet-fed animals (Figs. 3 and 4). The increase in NKCC1 protein levels under salt restriction was further elevated upon loss of Nedd4L (Fig. 3), and mRNA levels of this transporter paralleled the increase in its protein expression (Fig. 3). In the case of γENaC, Nedd4L depletion greatly increased the abundance of its cleaved, active form upon salt restriction (Fig. 4G, boxed). Together, these results suggest that a low salt diet elevates βγENaC protein abundance and ENaC activity but does not enhance NKCC1 activity despite increased mRNA and protein expression.

Regulation of NKCC1 Abundance by Nedd4L in the Colon Does Not Involve NKCC1 or Sgk1 Phosphorylation or the WNK1/3-SPAK Pathway

Nedd4L was recently found to degrade the (aldosterone-inducible) PY motif-containing isoform of the kinase WNK1 in the kidney and thus to regulate NCC activity (25); this raises the possibility that Nedd4L deficiency in the colon may stabilize WNK1 and thus enhance the NKCC1 activation we observed here, similar to its effect on NCC in the kidney. To test this possibility, we analyzed the abundance of WNK1 as well as activation of the WNK-target kinase SPAK (or its relative OSR1) in controls and Nedd4L KO colons after (or not) a low salt diet to elevate plasma aldosterone. Fig. 7 shows that loss of Nedd4L in the colon did not affect the abundance of WNK1 or phosphorylation (activation) of colonic SPAK (pS375-SPAK). Phosphorylation of OSR1 (p325-OSR1), presumably recognized by the same phosphor-antibody used for pSPAK, was very low or undetected in our preparations. A salt restriction diet also did not affect WNK1 or SPAK abundance or activation, respectively (Fig. 7). These data suggest that the inhibitory effect of Nedd4L on NKCC1 abundance and function in the distal colon likely does not involve WNK1 or pSPAK (or pOSR1).

FIGURE 7.

Lack of an increase in WNK1 levels and SPAK or NKCC1 phosphorylation upon knock-out of Nedd4L in the distal colon. Immunoblot analysis of WNK1 (A), phosphorylated SPAK (pSPAK) (B), or phosphorylated NKCC1 (pNKCC1) (C) in lysates collected form colonic epithelia of Nedd4L knock-out (KO, tamoxifen-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2) or control mice (3 mice each) following (or not) a low salt diet. Salt restriction is included in panels A and B. In panel C knock-out mice labeled KO1, KO2, and KO3 and their corresponding controls represent individual mice. treat, treatment of Hek293T cells stably expressing NKCC1 with low Cl−/hypotonic solution for 1 h in the presence of 500 nm Ser(P)/Thr(P) phosphatase inhibitor, calyculin A.

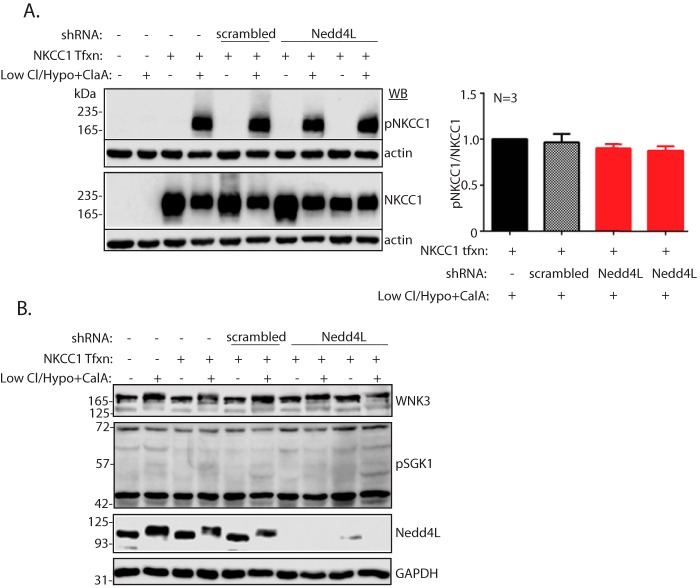

We next tested whether NKCC1 is phosphorylated upon loss of Nedd4L, as it was previously reported that NKCC1 phosphorylation is associated with its activation (26). As shown in Fig. 7C, we were not able to detect phosphorylation of NKCC1 in the colons of our mice even though we observed strong NKCC1 phosphorylation in Hek293T cells stably expressing NKCC1 and treated with low Cl−/hypotonic solution plus the phosphatase inhibitor calyculin A (a maneuver known to cause NKCC1 phosphorylation; Ref. 26). Because we could not detect NKCC1 phosphorylation in the colons of our mice, we tested for such phosphorylation in the NKCC1-expressing Hek293T cells depleted of Nedd4L and treated with low Cl−/hypotonic solution plus calyculin A; our results revealed no effect of Nedd4L depletion on NKCC1 phosphorylation (Fig. 8A) or SGK1 phosphorylation (pSGK1) or abundance of WNK3 (Fig. 8B), which is known to regulate NKCC1 in some epithelial cells (27). Interestingly, we found that such low Cl−/hypotonic treatment led to the appearance of slower migrating Nedd4L and WNK3 proteins (Fig. 8B), suggesting they are phosphorylated by this treatment (the pNedd4L antibodies, kindly provided by Dr. O. Staub, University of Lausanne, were not sensitive enough to detect endogenous pNedd4L in these cells). Collectively, our results suggest that Nedd4L normally suppresses expression and function of NKCC1 in the colon, a suppression that likely does not involve the WNK/SPAK pathway.

FIGURE 8.

Nedd4L depletion by shRNA in Hek293T cells (with/without Cl− depletion) did not affect NKCC1 or SGK1 phosphorylation or WNK3 abundance. Hek293T cells were incubated (or not) in low Cl−/hypotonic solution for 1 h in the presence of 500 nm calyculin A (Low Cl/Hypo+CalA) to activate NKCC1, and expression of NKCC1 or phosphorylated NKCC1 (pNKCC1) (A) or WNK3 or pSGK1 (B) was analyzed by immunoblotting. The right panel in A represents quantification of pNKCC1/NKCC1 levels in the indicated treatments of three independent experiments (mean ± S.E.), showing no differences in activated NKCC1 (pNKCC1) in the presence/absence of Nedd4L (the two red bars represent Nedd4L knockdown with two different shRNAs). Tfxn, transfection.

Discussion

ENaC is a well established target of Nedd4L-mediated ubiquitination, endocytosis, and degradation (1, 3, 5, 28). The identification here of NKCC1 as an important colonic target of Nedd4L is novel. NKCC1 is a basolateral transporter that supplies the intestinal epithelium with Cl−, which is then secreted via CFTR or other Cl− channels from the apical membrane (22, 29, 30). NKCC1 is involved in cell volume regulation and reported to be activated by reduced cell volume or intracellular Cl− concentrations as well as by phosphorylation by SPAK/OSR1 downstream of WNK3 kinase (27), a pathway that also activates the Na+/Cl− co-transporter NCC (19, 30). However, in the distal colon, normal or low salt diet did not affect WNK1 abundance or SPAK phosphorylation. As predicted, loss of Nedd4L, which would have been expected to function downstream of these proteins (if at all), did not alter WNK1/SPAK levels/phosphorylation. Moreover, in cells transfected with NKCC1 and depleted of Nedd4L, although we observed phosphorylation of NKCC1 (and likely Nedd4L and WNK3, but not SGK1) by low Cl−/hypotonic treatment, NKCC1 phosphorylation was not dependent on the presence of Nedd4L. Collectively, our results suggest that Nedd4L-mediated regulation of NKCC1 in the distal colon (and transfected Hek293T cells) may not involve the WNK-SPAK pathway. In accordance, a recent report suggested that WNK3 can bypass the SPAK and SGK1/Nedd4L-mediated regulation of NCC (31), suggesting that more than one pathway is responsible for regulating this family of co-transporters. Moreover, it is clear now that the contribution of SGK1, WNKs, and SPAK/OSR1 to the regulation of Na+ transport (including NKCC1) varies between different tissues and cell types (e.g. Refs. 32 and 33).

Whereas it is not known how ablation of Nedd4L affects expression and function of colonic NKCC1 we describe here (see below), our results suggest this effect does not involve direct binding between Nedd4L and NKCC1 or regulation of NKCC1 ubiquitination by Nedd4L. In fact, unlike its kidney NKCC2 relative, NKCC1 does not possess a PY motif. Instead, it seems more likely that Nedd4L indirectly affects mRNA and protein abundance by as yet an unknown pathway(s).

It was recently found that Nedd4L co-immunoprecipitates with NCC (likely via an indirect association) and targets NCC for degradation in the kidney (18, 19). Moreover, a recently identified alternatively spliced WNK1 isoform containing PY motifs binds Nedd4L and links it to the aldosterone-SGK1-Nedd4L-NCC pathway (25). Our inability to show Nedd4L/NKCC1 co-immunoprecipitation, WNK1 stabilization, or SPAK phosphorylation/activation lends further support to our above-mentioned notion that Nedd4L-mediated regulation of NKCC1 in the distal colon may be mediated by a different pathway.

Our analysis of levels of colonic NKCC1 revealed it was elevated upon ablation of Nedd4L. However, levels of αENaC or βENaC were not significantly altered under a normal salt diet, and those of (un-cleaved) γENaC were mildly increased. Because αENaC is a critical subunit for ENaC function, these results would suggest that Nedd4L has a more critical role in regulating NKCC1 than ENaC in the distal colon under a normal salt diet as also suggested by our Isc data. This is reminiscent of the stronger effect of Nedd4L on NCC relative to ENaC in the kidney (19). Under a low salt diet, however, ENaC-mediated Isc predominates in the colon and is no longer dependent on the presence of Nedd4L. This elevated ENaC-mediated Isc is accompanied by increased β and cleaved γ (but not α) ENaC expression. Interestingly, a high salt diet led to elevated β and γ (but not α) ENaC expression in the distal nephron of Nedd4L KO mice (19). These observations point to the fact that even though αENaC is required for maximal channel activity (9), β and γ ENaC play an equally important role in the salt-sensing response of the channel.

Despite ablation of Nedd4L in the distal colon of adult mice or during their development, which leads to elevated Isc across the distal colon epithelia, the Nedd4L knock-out mice are viable. Because deletion of αENaC or its activator CAP/Prss8 in the distal colon of mice does not affect viability, likely due to compensation by the kidney renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (7), it is possible that excess NKCC1 (and possibly ENaC) caused by depletion of Nedd4L in the colon may be also compensated for by the kidney to prevent lethal hypertension.

Collectively, our work identified NKCC1 as an important target for Nedd4L in the distal colon, especially under a normal diet, underscoring the role of Nedd4L in regulating salt/fluid absorption in specific epithelia, with variable targets in the different tissues; for example, ENaC in the lung (20, 21), NCC and ENaC in the distal nephron (18, 19), the PY motif-containing NHE3 and NKCC2 (34, 35) in the proximal nephron, and NKCC1 and ENaC in the distal colon, shown here.

Experimental Procedures

Generation of Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 (and Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-Cre) Mice

Nedd4Lf/f mice (20) were crossed to Vil-CreERT2 mice (kindly provided by Dr. Sylvie Robin, Paris) to generate Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 on a C57Bl/6J background. The resulting heterozygote Nedd4Lf/+ mice with Vil-CreERT2 (identified by genotyping) were crossed again to obtain the Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 line. A similar approach was used to generate a second line, Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-Cre, by crossing Nedd4Lf/f mice with a constitutive Vil-Cre driver mice (The Jackson Laboratory, B6.Cg-Tg(Vil1-cre)1000Gum/J, also known as Vil-Cre 1000). For the Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice, Nedd4L knock-out was induced by intraperitoneal injection of Tam (40 mg/kg body weight) at 6 weeks of age for 3 days consecutively. Distal colons from induced mice were used 2–3 weeks after induction. Nedd4Lf/f and uninduced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice were used as controls and combined for data analyses, as they exhibited the same (normal) phenotype. For a low salt diet, animals were fed with food containing 0.2% NaCl (#TD.09756, Envigo) for 3 weeks (simultaneously with Tam induction) before analysis of the colons, as above.

Ussing Chamber Assays

Distal colon from Nedd4Lf/f Vil-CreERT2 mice (or Nedd4Lf/f Vil-Cre) or Nedd4Lf/f controls were analyzed for Isc on Ussing chamber (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The buffer used in the assay contained 1× Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) supplemented with 21 mm NaHCO3, 1.2 mm CaCl2, and 1.2 mm MgCl2. Once the resting Isc was stabilized, 10 μm amiloride (Sigma) was added to the apical side to measure the amiloride-sensitive ENaC current. After amiloride current stabilization, 200 μm bumetanide (Sigma) was added to the basal side of the intestinal tissues to measure NKCC1 activity. All measurements are expressed as μA/cm2. Chloride (Cl−) depletion was carried out by substitution of the NaCl in the buffer on the basal side with sodium gluconate (Sigma) after the initial Isc stabilization.

Immunoblotting

Nedd4L knock-out was confirmed by Western blotting (WB) performed on epithelial cells harvested from the distal colons of Nedd4Lf/f (control), Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-Cre (control), or Tam-induced Nedd4Lf/f;Vil-CreERT2 mice by incubating the distal colons in 10 mm EDTA, PBS solution in a 37 °C shaking water bath to dissociate intestinal epithelial cells. Dissociated cells were washed with PBS and lysed in lysis buffer (50 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, 10% glycerol (v/v), 1% Triton X-100 (v/v) plus protease inhibitors (1 mm PMSF, 10 μm of aprotinin, pepstatin, and leupeptin each). Lysates were then immunoblotted with anti-Nedd4L antibodies (1:1000, #4013, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) to confirm Nedd4L knock-out. The levels of ENaC and NKCC1 in these cells were assessed using the following antibodies: αENaC (#SPC403D polyclonal antibodies, StressMarg, Victoria, BC, Canada); β and γ ENaC, a kind gift from Dr. J. Loffing, Zurich; NKCC1 (#ab59791, 1:1000, Abcam, Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Anti WNK1 poly clonal goat IgG (#AF2849, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), which recognizes the region encompassing Ser-813–Ser-1173 was used to detect levels of WNK1; this antibody is directed toward a region that includes exons 11–12, which encompasses the WNK1 variant containing the PY motifs (25). Rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-SPAK antibody (Ser-373)/phospho-OSR1 antibody (Ser-325) was from EMD Millipore (#07-2273) and was used on colonic lysate lysed in the presence of protease inhibitors (described above) and phosphatases inhibitors (#04906845001, PhosStop, Roche Applied Science).

Phosphorylation Analysis

Hek293T cells stably expressing HA-tagged NKCC1 were generated by transfecting Hek293T Cells with C-terminally HA-tagged NKCC1 in pcDNA3.1/Zeo vector. Nedd4L stable knockdown lines were subsequently generated by transfecting the Nedd4L shRNA pGIPz constructs (V2LHS_80459 and V2LHS_300779) or scramble control (RHS4348), from GE Dharmacon into the NKCC1 expressing line. NKCC1 stable expression and knockdowns of Nedd4L were verified by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody (#901515, Biolegend, San Diego, CA) and anti-Nedd4L antibody (#4013, Cell Signaling) respectively. For analysis of phosphorylation, Hek293T cells, Hek293T-NKCC1-HA cells, and Hek293T-NKCC1-HA cells with Nedd4L-shRNAs or the scramble control were cultured in duplicate: one set of the cells from each line was treated for 1 h at room temperature with low Cl−/hypotonic buffer (67.5 mm sodium gluconate, 2.5 mm potassium gluconate, 0.25 mm CaCl2, 0.25 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm Na2HPO4, 0.5 mm Na2SO4, and 7.5 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) with 500 nm calyculin A (ab141784, Abcam). Treated cells were lysed in the presence of protease inhibitor mixture plus PhosStop mixture (as above) and 500 nm calyculin A. The others set of cells was lysed directly with lysis buffer. Cell lysates were subject to immunoblotting for phospho-NKCC1 (pNKCC1, Thr-212/Thr-217) antibody (ABS1004, EMD Millipore), phospho-SGK (pSGK1, Ser-422) antibody (sc-16745, Santa Cruz), and WNK3 antibody (PA5–43188, Thermo Scientific). Lysed colonic epithelial cells were also probed with anti pNKCC1 antibodies, as above.

Co-IP Assays

C-terminally HA-tagged NKCC1 in pcDNA3.1 was generated by PCR from a template NKCC1 (VeraClone, #RDC0509, R&D Systems), HA-tagged angiomotin (AMOT, positive control known to bind Nedd4L; Ref. 36), V5-tagged Nedd4L, or Nedd4L(CS) (a catalytically inactive mutant of Nedd4L; Ref. 5) and transfected into Hek293T cells. Cells were lysed in lysis buffer as above. Lysates were analyzed for the interaction between Nedd4L and NKCC1 by IP with either HA (#901515, Biolegend) or V5 antibody (#MCA1360, AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC) and immunoblotting for V5 or HA, respectively.

Author Contributions

C. J. carried out all the experiments and analyzed the data. H. K. provided critical reagents. D. R. designed the project, helped in data analysis, and wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Johannes Loffing (University of Zurich) for the anti-β and -γ ENaC antibodies and O. Staub (Lausanne University) for anti-pNedd4L antibodies.

This work was supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR MOP-130422) and by Cystic Fibrosis Canada (to D. R.). The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests with the content of this article.

- Nedd4

- neuronal precursor cell expressed developmentally down-regulated 4

- ENaC

- epithelial Na+ channel

- Tam

- tamoxifen

- CFTR

- cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator

- co-IP

- co-immunoprecipitation

- Isc

- short circuit current

- WB

- Western blotting.

References

- 1. Kamynina E., Debonneville C., Bens M., Vandewalle A., and Staub O. (2001) A novel mouse Nedd4 protein suppresses the activity of the epithelial Na+ channel. FASEB J. 15, 204–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rotin D., and Staub O. (2012) Nedd4-2 and the regulation of epithelial sodium transport. Front. Physiol. 3, 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Abriel H., Loffing J., Rebhun J. F., Pratt J. H., Schild L., Horisberger J. D., Rotin D., and Staub O. (1999) Defective regulation of the epithelial Na+ channel by Nedd4 in Liddle's syndrome. J. Clin. Invest. 103, 667–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou R., Patel S. V., and Snyder P. M. (2007) Nedd4-2 catalyzes ubiquitination and degradation of cell surface ENaC. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 20207–20212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lu C., Pribanic S., Debonneville A., Jiang C., and Rotin D. (2007) The PY motif of ENaC, mutated in Liddle syndrome, regulates channel internalization, sorting and mobilization from subapical pool. Traffic 8, 1246–1264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Duc C., Farman N., Canessa C. M., Bonvalet J. P., and Rossier B. C. (1994) Cell-specific expression of epithelial sodium channel α, β, and γ subunits in aldosterone-responsive epithelia from the rat: localization by in situ hybridization and immunocytochemistry. J. Cell Biol. 127, 1907–1921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Malsure S., Wang Q., Charles R. P., Sergi C., Perrier R., Christensen B. M., Maillard M., Rossier B. C., and Hummler E. (2014) Colon-specific deletion of epithelial sodium channel causes sodium loss and aldosterone resistance. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 25, 1453–1464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rossier B. C., Staub O., and Hummler E. (2013) Genetic dissection of sodium and potassium transport along the aldosterone-sensitive distal nephron: importance in the control of blood pressure and hypertension. FEBS Lett. 587, 1929–1941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Canessa C. M., Schild L., Buell G., Thorens B., Gautschi I., Horisberger J. D., and Rossier B. C. (1994) Amiloride-sensitive epithelial Na+ channel is made of three homologous subunits. Nature 367, 463–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schild L., Lu Y., Gautschi I., Schneeberger E., Lifton R. P., and Rossier B. C. (1996) Identification of a PY motif in the epithelial Na+ channel subunits as a target sequence for mutations causing channel activation found in Liddle syndrome. EMBO J. 15, 2381–2387 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Staub O., Dho S., Henry P., Correa J., Ishikawa T., McGlade J., and Rotin D. (1996) WW domains of Nedd4 bind to the proline-rich PY motifs in the epithelial Na+ channel deleted in Liddle's syndrome. EMBO J. 15, 2371–2380 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Staub O., Gautschi I., Ishikawa T., Breitschopf K., Ciechanover A., Schild L., and Rotin D. (1997) Regulation of stability and function of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) by ubiquitination. EMBO J. 16, 6325–6336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Firsov D., Schild L., Gautschi I., Mérillat A. M., Schneeberger E., and Rossier B. C. (1996) Cell surface expression of the epithelial Na+ channel and a mutant causing Liddle syndrome: a quantitative approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 15370–15375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lifton R. P., Gharavi A. G., and Geller D. S. (2001) Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell 104, 545–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shi P. P., Cao X. R., Sweezer E. M., Kinney T. S., Williams N. R., Husted R. F., Nair R., Weiss R. M., Williamson R. A., Sigmund C. D., Snyder P. M., Staub O., Stokes J. B., and Yang B. (2008) Salt-sensitive hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy in mice deficient in the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4-2. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 295, F462–F470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Debonneville C., Flores S. Y., Kamynina E., Plant P. J., Tauxe C., Thomas M. A., Münster C., Chraïbi A., Pratt J. H., Horisberger J. D., Pearce D., Loffing J., and Staub O. (2001) Phosphorylation of Nedd4-2 by Sgk1 regulates epithelial Na+ channel cell surface expression. EMBO J. 20, 7052–7059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bhalla V., Daidié D., Li H., Pao A. C., LaGrange L. P., Wang J., Vandewalle A., Stockand J. D., Staub O., and Pearce D. (2005) Serum- and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase 1 regulates ubiquitin ligase neural precursor cell-expressed, developmentally down-regulated protein 4–2 by inducing interaction with 14-3-3. Mol. Endocrinol. 19, 3073–3084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Arroyo J. P., Lagnaz D., Ronzaud C., Vázquez N., Ko B. S., Moddes L., Ruffieux-Daidié D., Hausel P., Koesters R., Yang B., Stokes J. B., Hoover R. S., Gamba G., and Staub O. (2011) Nedd4-2 modulates renal Na+-Cl− cotransporter via the aldosterone-SGK1-Nedd4-2 pathway. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22, 1707–1719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ronzaud C., Loffing-Cueni D., Hausel P., Debonneville A., Malsure S. R., Fowler-Jaeger N., Boase N. A., Perrier R., Maillard M., Yang B., Stokes J. B., Koesters R., Kumar S., Hummler E., Loffing J., and Staub O. (2013) Renal tubular NEDD4–2 deficiency causes NCC-mediated salt-dependent hypertension. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 657–665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kimura T., Kawabe H., Jiang C., Zhang W., Xiang Y. Y., Lu C., Salter M. W., Brose N., Lu W. Y., and Rotin D. (2011) Deletion of the ubiquitin ligase Nedd4L in lung epithelia causes cystic fibrosis-like disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3216–3221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boase N. A., Rychkov G. Y., Townley S. L., Dinudom A., Candi E., Voss A. K., Tsoutsman T., Semsarian C., Melino G., Koentgen F., Cook D. I., and Kumar S. (2011) Respiratory distress and perinatal lethality in Nedd4-2-deficient mice. Nat. Commun. 2, 287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kunzelmann K., and Mall M. (2002) Electrolyte transport in the mammalian colon: mechanisms and implications for disease. Physiol. Rev. 82, 245–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frindt G., Ergonul Z., and Palmer L. G. (2008) Surface expression of epithelial Na+ channel protein in rat kidney. J. Gen. Physiol. 131, 617–627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Loffing J., Pietri L., Aregger F., Bloch-Faure M., Ziegler U., Meneton P., Rossier B. C., and Kaissling B. (2000) Differential subcellular localization of ENaC subunits in mouse kidney in response to high and low Na+ diets. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 279, F252–F258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Roy A., Al-Qusairi L., Donnelly B. F., Ronzaud C., Marciszyn A. L., Gong F., Chang Y. P., Butterworth M. B., Pastor-Soler N. M., Hallows K. R., Staub O., and Subramanya A. R. (2015) Alternatively spliced proline-rich cassettes link WNK1 to aldosterone action. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 3433–3448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Flemmer A. W., Gimenez I., Dowd B. F., Darman R. B., and Forbush B. (2002) Activation of the Na-K-Cl cotransporter NKCC1 detected with a phospho-specific antibody. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 37551–37558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kahle K. T., Rinehart J., de Los Heros P., Louvi A., Meade P., Vazquez N., Hebert S. C., Gamba G., Gimenez I., and Lifton R. P. (2005) WNK3 modulates transport of Cl- in and out of cells: implications for control of cell volume and neuronal excitability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 16783–16788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kabra R., Knight K. K., Zhou R., and Snyder P. M. (2008) Nedd4-2 induces endocytosis and degradation of proteolytically cleaved epithelial Na+ channels. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 6033–6039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gamba G. (2005) Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of electroneutral cation-chloride cotransporters. Physiol. Rev. 85, 423–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Markadieu N., and Delpire E. (2014) Physiology and pathophysiology of SLC12A1/2 transporters. Pflugers Arch. 466, 91–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lagnaz D., Arroyo J. P., Chávez-Canales M., Vázquez N., Rizzo F., Spirlí A., Debonneville A., Staub O., and Gamba G. (2014) WNK3 abrogates the NEDD4–2-mediated inhibition of the renal Na+-Cl− cotransporter. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 307, F275–F286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rozansky D. J., Wang J., Doan N., Purdy T., Faulk T., Bhargava A., Dawson K., and Pearce D. (2002) Hypotonic induction of SGK1 and Na+ transport in A6 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 283, F105–F113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Susa K., Kita S., Iwamoto T., Yang S. S., Lin S. H., Ohta A., Sohara E., Rai T., Sasaki S., Alessi D. R., and Uchida S. (2012) Effect of heterozygous deletion of WNK1 on the WNK-OSR1/SPAK-NCC/NKCC1/NKCC2 signal cascade in the kidney and blood vessels. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 16, 530–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. No Y. R., He P., Yoo B. K., and Yun C. C. (2014) Unique regulation of human Na+/H+ exchanger 3 (NHE3) by Nedd4-2 ligase that differs from non-primate NHE3s. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 18360–18372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wu J., Liu X., Lai G., Yang X., Wang L., and Zhao Y. (2013) Synergistical effect of 20-HETE and high salt on NKCC2 protein and blood pressure via ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Hum. Genet. 132, 179–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang C., An J., Zhang P., Xu C., Gao K., Wu D., Wang D., Yu H., Liu J. O., and Yu L. (2012) The Nedd4-like ubiquitin E3 ligases target angiomotin/p130 to ubiquitin-dependent degradation. Biochem. J. 444, 279–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]