Abstract

State prescription drug monitoring programs are promising tools to rein in the epidemic of prescription opioid overdose. We used data from a national survey to assess the effects of the programs on the prescribing of opioid analgesics and other pain medication in ambulatory care settings at the point of care in twenty-four states from 2001 to 2010. We found that implementation of a prescription drug monitoring program was associated with more than a 30 percent reduction in the rate of prescribing of Schedule II opioids. This reduction was seen immediately following the launch of the program and was maintained in the second and third years afterward. Effects on overall opioid prescribing and prescribing of nonopioid analgesics were limited. Increased utilization of these programs and the adoption of new policies and practices governing their use may have contributed to sustained effectiveness. Future studies are needed to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of these policies.

Prescription opioid pain relievers were responsible for more than 16,000 overdose deaths in the United States in 2013.[1] More than ten million Americans reported using opioids nonmedically in 2014.[2] Nonmedical users may obtain controlled substances by getting multiple prescriptions from multiple prescribers, a behavior known as “doctor shopping,”[3,4] or from friends or relatives for whom the substances were prescribed, a practice known as “diversion.”[5] Prescribers—generally primary care physicians and dentists, as opposed to pain medicine specialists[6]—are thus an important link in helping address this deadly drug overdose epidemic. Information on potential misuse and abuse of prescription opioids can assist these prescribers in striking a balance between alleviating pain for patients and ensuring safe prescribing.

Prescription drug monitoring programs are statewide databases that gather information from pharmacies on dispensed prescriptions of controlled substances and, as such, are promising tools to help combat the prescription opioid epidemic. Prescribers, pharmacists, law enforcement agencies, and medical licensure boards are among the typical users of these databases. Prescription drug monitoring programs date back to the late 1930s. A new wave of implementation began in the early 2000s, and all states except Missouri have either implemented or upgraded their prescription drug monitoring programs or have enacted legislation to do so.[7] Prescription drug monitoring programs implemented since the late 1990s are all electronic instead of paper-based; typically allow users, especially prescribers, access by means of an online portal; and cover a wider range of controlled substances, compared to drug monitoring programs implemented earlier.

Effective prescription drug monitoring programs can help change prescriber behavior by identifying patients at a high risk of doctor shopping or diversion. They also allow law enforcement agencies and medical licensure boards to monitor aberrant prescribing practices. Evidence is limited, however, about the extent to which the implementation of prescription drug monitoring programs has actually changed opioid prescribing at the point of care.

Several studies have linked prescription drug monitoring program implementation in selected states or years with trends in aggregate opioid consumption[8–13] or population rates of opioid abuse, opioid-related inpatient admissions, and overdose deaths.[8–11,14,15] These studies have had mixed findings.[16] Survey[12] or observational[17] studies based on data from a single academic medical center found substantial changes in opioid prescribing rates from before to after use of a prescription drug monitoring program. Meanwhile, there is a concern that the overall low rate of registration with and low use of such programs by prescribers[18] may limit the programs’ effectiveness. Evidence at the national level from recent implementations of prescription drug monitoring programs is needed to inform the next phase of state policy making.

In this study, we assessed the effects of recent state implementation of prescription drug monitoring programs on the prescribing of opioids and other pain medication to manage pain in ambulatory care settings. We used national data reflecting prescribing decisions at the point of care that covered a ten-year period of implementation of electronic prescription drug monitoring programs in about half the states. Because it may take time for prescribers to become aware of and use a prescription drug monitoring program, we also assessed whether the effects of implementation became stronger the longer a program had been in effect.

Study Data And Methods

Data

The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) is a nationally representative annual survey of ambulatory visits to nonfederally employed office-based physicians that is conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics.[19] Each year people in a systematic sample of physicians (based on the American Medical Association’s Physician Masterfile) and clinicians at community health centers are asked to complete a survey for about thirty visits that occurred during a randomly selected one-week period. In 2010 NAMCS had an unadjusted physician response rate of 58 percent.[19]

The survey collects patient, visit, and clinician or practice information. Of particular relevance to this study is information on reasons for a particular visit, diagnoses pertaining to the visit, and information on up to eight medications that were prescribed or continued at the visit. No dosage information was collected for the medications. The National Center for Health Statistics applies rigorous quality assurance procedures to NAMCS data collection and processing, which contributes to a keying and coding error rate of less than 1 percent.[20]

We used restricted NAMCS data for the period 2001–10, which also identified the state in which the office visit took place. Changes to the sample design and survey instruments were minimal during the study period. The medication classification system, however, experienced a major change in 2006. We adopted SAS software programs developed by the National Center for Health Statistics to map drug characteristics for data before 2006 onto the current system to enable longitudinal analysis.[21]

Study Population And Sample

Our study population consisted of patients ages eighteen and older who reported pain as one of the reasons for a visit to an office-based physician. Using NAMCS’s coding system, we identified a set of codes that represented pain, soreness, discomfort, aches, cramps, spasms, burning, or stinging.[22] Our main analysis was restricted to office visits that occurred in one of the twenty-four states that had implemented a prescription drug monitoring program during the study period. Online Appendix Exhibit A1 provides information on date of implementation, controlled substances monitored, and other policies and regulations governing the use of each of the twenty-four prescription drug monitoring programs.[23]

Measures

Our main outcomes of interest were both dichotomous—having at least one Schedule II opioid analgesic and having at least one opioid of any kind prescribed or continued at a pain-related ambulatory care visit. All opioid analgesics are either Schedule II (the category with the highest potential of abuse and dependency among all drugs with currently accepted medical use) or Schedule III (a category with a lower potential for abuse and dependency than Schedule II). Identification of opioid analgesics was initially based on the Multum drug ontology used by NAMCS.[22] A clinician investigator further reviewed all generic drug names included in the category of opioid analgesics to exclude drugs that had been misclassified or were not typically used for pain management.

We examined two additional outcomes. First was an indicator of at least one pain medication (opioid analgesics; nonopioid analgesics; anticonvulsants; muscle relaxants; Cymbalta or other tricyclic antidepressants, which are frequently prescribed for pain; and topical anesthetics) prescribed or continued during a visit where the patient presented with pain. Second was an indicator of at least one nonopioid analgesic (a subset of pain medications that includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, salicylates, antimigraine agents, Cox-2 inhibitors, and analgesic combinations) similarly being prescribed or continued. These measures allowed us to examine whether prescribers substituted nonopioid pain medications for opioids.

We defined prescription drug monitoring program implementation as the date on which a state opened online access to its database to prescribers and dispensers. We obtained this information in part from the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws.[24] For those states whose information was missing from the state drug law database, we contacted state program administrators and searched legal databases and state websites for information. An ambulatory care visit was determined to be “postimplementation” if the visit occurred after the state provided user access to its database.

Analysis

We exploited the staggered implementation of prescription drug monitoring programs across states and compared the prescribing of opioids and other pain medication before and after implementation, using visits in states that had not yet implemented such programs as controls. Our main analysis focused on the twenty-four states that implemented a program during the study period. This was arguably a stronger study design than including states that had implemented a program before 2001 or had not yet implemented one by 2010, because it allowed states with proximal timing of implementation to serve as controls for each other. To assess the robustness of our findings, we included all states in a sensitivity analysis.

We estimated a linear probability regression model and a logistic regression model to check the robustness of results for each prescribing outcome. The main independent variable was the postimplementation status of a given office visit. We included a set of dichotomous state indicators, one for each state (state fixed effects), to control for differences between states that did not change over time and a set of year fixed effects to control for nationwide trends in pain medication prescribing. Each model also controlled for patient characteristics (age, sex, insurance type, and household income in the practice’s ZIP code), visit characteristics (the patient was new to the practice; pain was a new condition; having a current diagnosis of cancer, which applied to 1 percent of the entire sample; musculoskeletal versus other pain; and number of chronic conditions recorded for the visit), and physician characteristics (sex, primary care provider status, and practice size as measured by the number of physicians).

We first estimated the average effect of implementation of a prescription drug monitoring program regardless of how long the program had been in operation. We then conducted an analysis that allowed the effect of the drug monitoring program to differ by time since implementation. We did this by eliminating the postimplementation indicator but including indicators that a given office visit occurred during 0–6, 7–12, 13–18, 19–24, or 25 or more months postimplementation.

Limitations

The study had several limitations. First, we did not have data to determine the appropriateness of opioid or other pain medication prescribing or nonprescribing. We therefore could not evaluate whether patients’ pain management needs were adequately met and whether this changed as a result of drug monitoring program implementation. However, given the sheer volume of opioid prescribing each year in the United States (enough to medicate every adult American for a month)[25] and the lack of evidence supporting long-term opioid use for chronic noncancer pain,[26] changes in opioid prescribing in response to the existence of prescription drug monitoring programs are likely to reflect a move toward more appropriate prescribing of pain medications among some prescribers.

Second, the medication data in NAMCS may be subject to reporting errors and are not the same as information on filled prescriptions captured in prescription drug claims. In addition, given the NAMCS survey design, medication recorded in the data reflect snapshots of physician prescription decisions instead of a complete picture of prescribing behaviors or patterns of a given physician. However, survey data based on medical records (instead of prescription claims) provide arguably better measures of prescribing decisions at the point of care, the construct of interest in this study.

Third, because of lags in data availability, our analysis was restricted to prescription drug monitoring programs implemented in the period 2001–10. The effects of program implementation in more recent years (2011–14) may differ from those in the past and should be examined in future studies.

Finally, to the extent that implementation of a prescription drug monitoring program in a state coincided with other reasons for changes in prescriber behaviors, the relationship we estimated may be associational and not causal.

Study Results

Our analytical sample contained 26,275 ambulatory care office visits for pain that took place in the twenty-four states that had implemented a prescription drug monitoring program during the period 2001–10. Patient, visit, and physician characteristics and study outcomes are summarized in online Appendix Exhibit A2.[23]

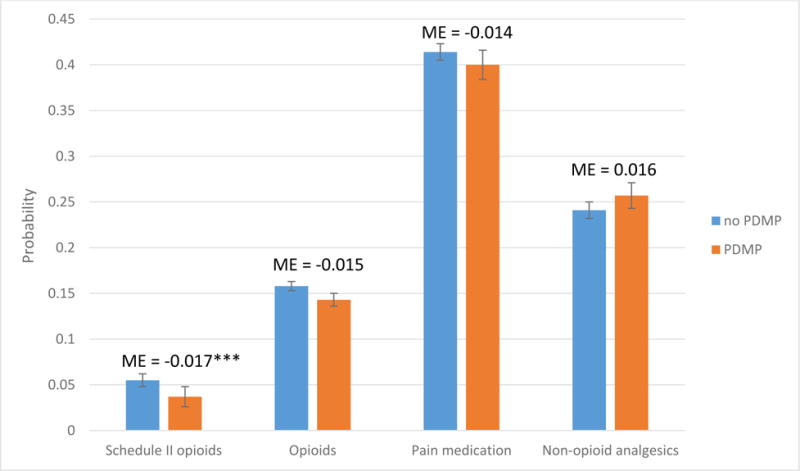

Five percent of the ten-year pooled sample of visits resulted in the prescription of at least one Schedule II opioid, 15 percent in at least one opioid analgesic of any kind, 41 percent in any pain medication, and 24 percent in at least one nonopioid analgesic. The results regarding prescription drug monitoring program effects are based on linear probability models. Logistic models produced very similar results. Full regression results for the linear and logistic models are available in Appendix Exhibits A3–A6.[23]

Overall Effect Of Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs

Our analysis indicated that the implementation of a prescription drug monitoring program was associated with a reduction in the prescribing of Schedule II opioids, opioids of any kind, and pain medication overall (Exhibit 1). The implementation of a program also slightly increased the prescribing of nonopioid analgesics. However, the only significant effect was on Schedule II opioid prescribing, in which there was a reduction in the probability of prescribing at an office visit with pain from 5.5 to 3.7 percent. This was a more than 30 percent reduction, relative to the rate of prescribing before implementation of a drug monitoring program.

EXHIBIT 1. Effects of the implementation of a prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) on the prescribing of opioid analgesics and other pain medications.

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2001–10 from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. NOTES The data shown are predicted probabilities of receiving or continuing a prescription for an opioid analgesic or other pain medication at a pain-related ambulatory care visit with and without a PDMP. The whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals. Schedule II opioids are explained in the text. ME is the marginal effect of a PDMP. ***p < 0.01

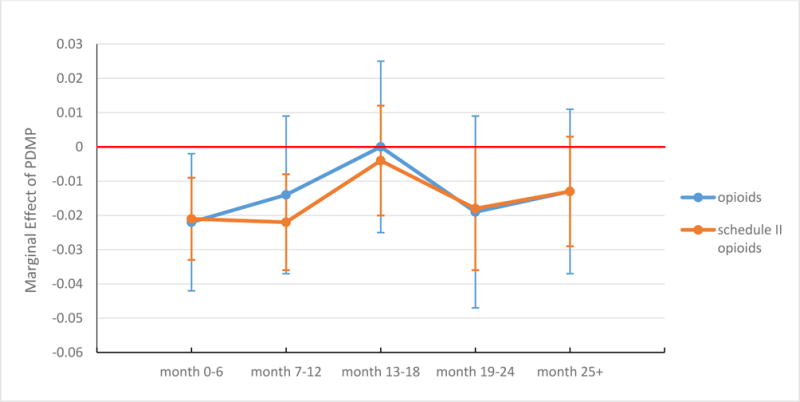

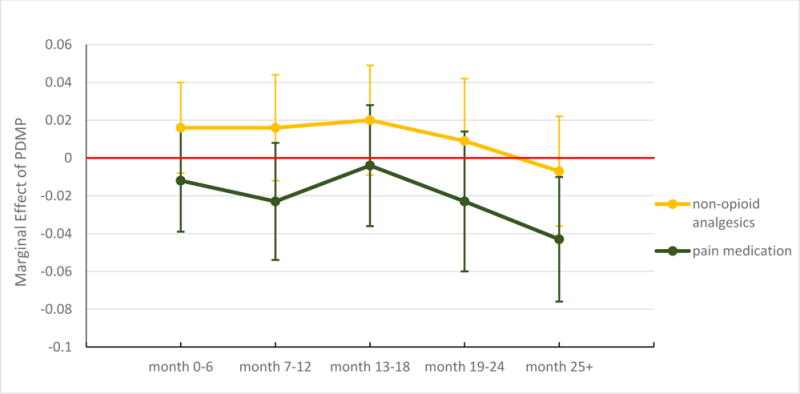

Effects By Time Since Implementation

In our analysis that allowed the effect to vary with time since implementation of a prescription drug monitoring program, we found a reduction in Schedule II opioid prescribing of 2.1 percentage points during the first six months of implementation, 2.2 percentage points in months 7–12, and 1.8 percentage points in months 19–24 (Exhibit 2). The effect was smaller and not significant at other times. Prescription drug monitoring programs were associated with a significant reduction (2.2 percentage points) in the prescribing of opioid analgesics of any kind in the first six months of implementation, but no subsequent reductions were significant. For overall pain medication prescribing, there was a significant reduction of 4.3 percentage points when a program was in its third year or later (Exhibit 3).

EXHIBIT 2. Effects of a prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) on the prescribing of opioid analgesics, by time since program implementation.

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2001–10 from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. NOTES The data shown are marginal effects of a PDMP on the probability of receiving a prescription for an opioid analgesic or a Schedule II opioid during a pain-related ambulatory care visit by time intervals since PDMP implementation. The whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

EXHIBIT 3. Effects of a prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) on the prescribing of any pain medication and of nonopioid analgesics, by time since implementation.

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2001–10 from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. NOTES The data shown are marginal effects of PDMP on the probability of receiving a prescription for pain medication or a nonopioid analgesic during a pain-related ambulatory care visit by time intervals since implementation. The whiskers represent 95% confidence intervals.

Our sensitivity analysis that included all states indicated an overall reduction in the prescribing of Schedule II opioids in response to implementation of a prescription drug monitoring program, although the effect was smaller than in the main analysis. An analysis that included all states and allowed the program effect to vary by time since implementation indicated a strong reduction in Schedule II opioid prescribing during the first year but not in subsequent time periods. Regression outputs for this sensitivity analysis are found in Appendix Exhibits A7 and A8.[23]

Discussion

Our analysis of the NAMCS data suggests that the recent wave of implementations of prescription drug monitoring programs was associated with a sizable reduction in the prescribing of Schedule II opioids—the subset of prescription opioids deemed to be at the highest risk of misuse and abuse—while having limited effects on the prescribing of opioid analgesics of any kind and of other pain medication. We also found that the effect of implementation on the prescribing of Schedule II opioids and all opioids was immediate, and that after the first six months, this effect remained strong for Schedule II opioids but was attenuated for opioids of any kind.

It is possible that the implementation of a prescription drug monitoring program by itself substantially raised awareness among prescribers about controlled substance misuse and abuse and made them more cautious when prescribing pain medications with a great potential for abuse and dependency. It is also possible that knowing that their prescribing was being “watched” deterred them from prescribing Schedule II opioids to some extent.

Our results also provide evidence that the effect on Schedule II opioid prescribing was not transient. Following some attenuation after the first year, the effect regained strength eighteen months after implementation. This longer-term effect could be a result of increased use of drug monitoring programs over time, which is the mechanism by which such programs are expected to work.

It could also result from increased adoption of state policies and practices that govern the use of prescription drug monitoring programs in recent years. Prominent examples of these policies include mandated registration of prescribers with prescription drug monitoring programs (policies that had been adopted by twenty states as of June 2014),[27] mandated use of the program by prescribers in certain circumstances (adopted by twenty-two states as of June 2014),[27] provision of unsolicited reports of the questionable use of controlled substances by patients to prescribers or of questionable prescribing practices to law enforcement officials or licensure boards (adopted by twenty-six states to varying extents in 2012),[28] and laws authorizing prescription monitoring program account holders (prescribers) to delegate access to nonprescribing staff members in their practices (adopted by thirty-six states and implemented by twenty-eight by 2014).[29] Because these policies and practices had been rapidly adopted after 2012, it is unlikely that they alone accounted for the sustained effects of initial program implementation during our study period (2001–10). The effectiveness of these policies needs to be further assessed as more recent data become available.

The reduction in the prescribing of Schedule II opioids associated with implementation of a drug monitoring program is encouraging because it suggests that providers are moving away from prescribing opioid analgesics that have the highest risks of abuse and dependency. Our additional analyses indicate that prescribing of Schedule III opioids, in contrast, did not change in a clinically or statistically significant way in response to implementation (Appendix Exhibit A9),[23] which dampens concerns that prescribers may have substituted Schedule III opioids for Schedule II opioids to some extent in their prescribing.[30]

A major subclass of Schedule III opioids—combination drugs containing hydrocodone, such as Vicodin and Lortab—was recently elevated to the category of Schedule II by the Drug Enforcement Administration,[31] based on the belief that the looser control of and relative ease in obtaining long-term supplies of these medications have fueled the rapid increase in opioid use over time. Our analysis of the NAMCS data indicates that in 2010 hydrocodone-containing combination opioids were prescribed in close to 50 percent of all ambulatory visits with an opioid prescription and in 63 percent of ambulatory visits with a Schedule III opioid prescription (data not shown). It remains to be seen whether the prescribing of these drugs will decrease in response to the reclassification, and whether prescribers will access drug monitoring databases more frequently when prescribing these drugs than they did before the reclassification.

It is worth noting that there might be substantial heterogeneity in how pain medication prescribing has responded or will respond to drug monitoring program policies across states. In an exploratory analysis in which we assigned specific drug monitoring program implementation indicators to the seventeen states with at least a hundred observations both before and after implementation, we found that eight states (Alabama, California, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Michigan, South Carolina, and Tennessee) had large reductions in the rate of Schedule II opioid prescribing (Appendix Exhibit A10),[23] while the other nine states had effect sizes that were close to zero. Such heterogeneity is likely to increase with the recent wave of state mandates and other policies governing the use of prescription drug monitoring programs.

Despite the almost universal implementation of drug monitoring programs among states, overall awareness and use of these programs among prescribers remains low.[12,32,33] A recent report by the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence at Brandeis estimated a median drug program registration rate of 35 percent among licensed prescribers who prescribed at least one controlled substance in the period 2010–12.[18] The limited effect of implementation that we found on overall opioid and pain medication prescribing can be partly explained by this low take-up. However, the increasing adoption of policies and practices by states governing the use of prescription drug monitoring programs, such as their mandatory registration, use, or both and the delegating of access authority, could potentially increase prescriber take-up and regular use.[7]

Conclusion

Our analysis of national data reflecting point-of-care prescribing practices for pain medication indicated that state implementation of prescription drug monitoring programs during the period 2001–10 was associated with more than a 30 percent reduction in the rate of prescribing of Schedule II opioid analgesics. This effect was immediate following the launch of user access to a program’s database and was sustained in the second and third years afterward. As prescription drug monitoring program policy making has shifted from implementation to enhancement, future research is needed to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of key policies and practices designed to promote the reach and effectiveness of these programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by pilot grants from the Center for Health Economics of Treatment Interventions for Substance Use Disorders, HCV, and HIV (CHERISH), a National Institute on Drug Abuse Center of Excellence (Grant No. P30DA040500) and the Translational Institute on Pain in Later Life at Cornell and Columbia Universities (Grant No. P30AG022845). Yuhua Bao is also supported by a career development award from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. K01MH090087). Bruce Schackman is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant No. P30DA040500). Harold Alan Pincus is supported by the Commonwealth Fund (Grant No. 20141104) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (through Grant No. UL1 TR000040). The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors thank Ashley Eggman for her excellent assistance with the manuscript and Cary Reid for helpful input on the revision of the paper.

Biographies

Yuhua Bao (yub2003@med.cornell.edu) is an associate professor of healthcare policy and research at Weill Cornell Medical College, in New York City.

Yijun Pan is a PhD candidate in economics at Cornell University, in Ithaca, New York.

Aryn Taylor is a PhD student in Policy Analysis and Management at Cornell University.

Sharmini Radakrishnan is a senior analyst at Abt Associates, in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Feijun Luo is a senior service fellow at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in Atlanta, Georgia.

Harold Alan Pincus is Vice Chair, Department of Psychiatry, Columbia University’s College of Physicians and Surgeons, and Director of Quality and Outcomes Research, New York Presbyterian Hospital in New York City.

Bruce R. Schackman is a professor of healthcare policy and research at Weill Cornell Medical College.

Notes

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. QuickStats: rates of deaths from drug poisoning and drug poisoning involving opioid analgesics—United States, 1999–2013 [Internet] Atlanta (GA): CDC; [last updated 2015 Jan 16; cited 2015 May 3]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6401a10.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2014 national survey on drug use and health: detailed tables [Internet] Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2015. Sep 10, [cited 2016 May 3]. Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-DetTabs2014/NSDUH-DetTabs2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hall AJ, Logan JE, Toblin RL, Kaplan JA, Kraner JC, Bixler D, et al. Patterns of abuse among unintentional pharmaceutical overdose fatalities. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2613–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White AG, Birnbaum HG, Schiller M, Tang J, Katz NP. Analytic models to identify patients at risk for prescription opioid abuse. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15(12):897–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.RTI International. Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: summary of national findings [Internet] Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [cited 2016 May 3]. (HHS Publication No. [SMA] 14-4863). Available from: http://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUHresultsPDFWHTML2013/Web/NSDUHresults2013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volkow ND, McLellan TA, Cotto JH, Karithanom M, Weiss SR. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions in 2009. JAMA. 2011;305(13):1299–301. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark T, Eadie J, Kreiner P, Strickler G (Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA) Prescription drug monitoring programs: an assessment of the evidence for best practices [Internet] Philadelphia (PA): Pew Charitable Trusts; 2012. Sep 20, [cited 2016 May 3]. Available from: http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/assets/0001/pdmp_update_1312013.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulozzi LJ, Kilbourne EM, Desai HA. Prescription drug monitoring programs and death rates from drug overdose. Pain Med. 2011;12(5):747–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2011.01062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paulozzi LJ, Stier DD. Prescription drug laws, drug overdoses, and drug sales in New York and Pennsylvania. J Public Health Policy. 2010;31(4):422–32. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2010.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reisman RM, Shenoy PJ, Atherly AJ, Flowers CR. Prescription opioid usage and abuse relationships: an evaluation of state prescription drug monitoring program efficacy. Subst Abuse. 2009;3:41–51. doi: 10.4137/sart.s2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simeone R, Holland L. An evaluation of prescription drug monitoring programs [Internet] Albany (NY): Simeone Associates Inc.; 2006. Sep 1, [cited 2016 May 3]. Available from: http://www.simeoneassociates.com/simeone3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman L, Williams KS, Coates J, Knox M. Awareness and utilization of a prescription monitoring program among physicians. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2011;25(4):313–7. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2011.606292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brady JE, Wunsch H, DiMaggio C, Lang BH, Giglio J, Li G. Prescription drug monitoring and dispensing of prescription opioids. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(2):139–47. doi: 10.1177/003335491412900207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li G, Brady J, Lang B, Giglio J, Wunsch H, DiMaggio C. Prescription drug monitoring and drug overdose mortality. Injury Epidemiology. 2014;1(9):9. doi: 10.1186/2197-1714-1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reifler LM, Droz D, Bailey JE, Schnoll SH, Fant R, Dart RC, et al. Do prescription monitoring programs impact state trends in opioid abuse/misuse? Pain Med. 2012;13(3):434–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2012.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haegerich TM, Paulozzi LJ, Manns BJ, Jones CM. What we know, and don’t know, about the impact of state policy and systems-level interventions on prescription drug overdose. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;145:34–47. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baehren DF, Marco CA, Droz DE, Sinha S, Callan EM, Akpunonu P. A statewide prescription monitoring program affects emergency department prescribing behaviors. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56(1):19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreiner P, Nikitin R, Shields TP (Heller School for Social Policy and Management, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA) Bureau of Justice Assistance Prescription Drug Monitoring Program performance measures report: January 2009 through June 2012 [Internet] Washington (DC): Bureau of Justice Assistance; [grantee feedback included 2014 Apr 4; cited 2016 May 3]. Available from: http://www.pdmpexcellence.org/sites/all/pdfs/BJA%20PDMP%20Performance%20Measures%20Report%20Jan%202009%20to%20June%202012%20FInal_with%20feedback.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Center for Health Statistics. NAMCS micro-data file documentation [Internet] Hyattsville, Maryland: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. [cited 2016 May 3 ] Available from: ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_statistics/NCHs/Dataset_Documentation/NAMCS/doc2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Center for Health Statistics. NAMCS data collection and processing [Internet] Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; [last reviewed 2015 Nov 6; cited 2016 May 3]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_data_collection.htm#namcs_collection. [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Center for Health Statistics. Trend analysis using NAMCS and NHAMCS drug data [Internet] Hyattsville (MD): NCHS; [last reviewed 2015 Nov 6; cited 2016 May 3]. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/trend_analysis.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, Gonzales R. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299(1):70–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 24.National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws [home page on the Internet] Charlottesville (VA): NAMSDL; c 2016 [cited 2016 May 3]. Available from: http://www.namsdl.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA, Hockenberry JM. Vital signs: variation among states in prescribing of opioid pain relievers and benzodiazepines—United States, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(26):563–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, Hansen RN, Sullivan SD, Blazina I, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):276–86. doi: 10.7326/M14-2559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence at Brandeis. Mandating PDMP participation by medical providers: current status and experience in selected states [Internet] Waltham (MA): The Center; 2014. Oct, [cited 2016 May 3]. (COE Briefing). Available from: http://www.pdmpexcellence.org/sites/all/pdfs/COE_briefing_mandates_2nd_rev.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence at Brandeis. Options for unsolicited reporting [Internet] Waltham (MA): The Center; 2014. Jan, [cited 2016 May 3]. (Guidance on PDMP Best Practices). Available from: http://pdmpexcellence.org/sites/all/pdfs/Brandeis_COE_Guidance_on_Unsolicited_Reporting_final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prescription Drug Monitoring Program Center of Excellence at Brandeis. PDMP delegate account systems [Internet] Waltham (MA): The Center; 2015. May, [cited 2016 May 3]. (COE Briefing). Available from: http://www.pdmpexcellence.org/sites/all/pdfs/COE%20Briefing%20on%20Delegate%20Account%20Systems.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wastila L, Bishop C. The influence of multiple copy prescription programs on analgesic utilization. J Pharm Care Symptom Control. 1996;4(3):3–19. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drug Enforcement Administration, Department of Justice. Schedules of controlled substances: rescheduling of hydrocodone combination products from schedule III to schedule II. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2014;79(163):49661–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrett K, Watson A. Physician perspectives on a pilot prescription monitoring program. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2005;19(3):5–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ulbrich TR, Dula CA, Green CG, Porter K, Bennett MS. Factors influencing community pharmacists’ enrollment in a state prescription monitoring program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2010;50(5):588–94. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.09089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.