Abstract

Background

Use of the plasticiser di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) blood bags poses a potential dilemma. The presence of DEHP in blood bags has been shown to be beneficial to red blood cells during storage by diminishing haemolysis. However, DEHP use in PVC may be carcinogenic or estrogenising. Vepoloxamer is a poloxamer with rheological and cytoprotective rheological properties and a favourable toxicity profile in clinical trials. We hypothesised that vepoloxamer may be sufficient to replace the plasticiser DEHP to prevent elevated haemolysis while conserving the biochemical and redox potential++ in RBCs stored for up to 42 days.

Materials and methods

Paired analyses of aliquots from pooled RBC suspensions of ABO identical donors were aseptically split into test storage containers (DEHP/PVC or DEHP-free/ethylene vinyl acetate [EVA]) supplemented with or without vepoloxamer (at concentrations of 0.1, 1, 5 or 7.89 mg/mL) and cold stored for up to 42 days.

Results

Vepoloxamer significantly prevented the increased haemolysis induced by the absence of DEHP in EVA bags in a dose-dependent manner by days 28 and 42 of storage (approx. 50% reduction of the maximum concentration of vepoloxamer; p<0.001). There was an inverse correlation between the concentration of vepoloxamer used and the haemolysis rate (r2=0.27, p<0.001) and a direct correlation between haemolysis and phosphatidylserine (PS) exposure (r2=0.42; p<0.01). Increased osmotic fragility and shear induced deformability of 42-day stored RBC in EVA bags was significantly corrected by the addition of vepoloxamer.

Discussion

Vepoloxamer, in a concentration-dependent fashion, is able to partly rescue the increased haemolysis and PS exposure induced by the absence of the commonly used plasticiser DEHP. These results provide initial but strong evidence to support vepoloxamer use to replace DEHP in long-term storage of RBC.

Keywords: blood, red blood cell, virus, pathogen, inactivation

Introduction

Di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) is a plasticiser produced commercially to provide flexibility to an otherwise rigid polyvinyl chloride (PVC)1 with concentrations in PVC of approximately 30%, although these can be up to 80%2,3. Since DEHP is non-covalently bound to the PVC polymer, its lipophilic nature means it can leach into the storage content of a container, especially when the surface comes into contact with lipid-containing fluids. The concentration of DEHP in whole blood (WB) or blood components can be efficiently measured4 and increases upon storage5,6, although absolute amounts depend on component composition and storage temperature. While most DEHP is found in fluid phase, especially bound to lipoproteins7, a small proportion can be associated with red blood cells (RBCs)8, resulting in intravenous exposure and circulating DEHP in blood9,10. The value of DEHP in RBC bags is not only related to the increased flexibility of the bag but also because it improves RBC survival during storage and after transfusion11. DEHP affects RBC integrity by inhibiting the deterioration of the RBC membrane, which prevents the haemolysis, microvesicle formation, and morphological changes that occur during refrigerated storage12. DEHP is associated with the RBC membrane and cytosol, and this is a potential mechanism for the increased RBC stability13. While the molecular mechanism of this protective role is not completely understood, some studies have demonstrated that DEHP protects against membrane damage by altering the interaction between phospholipids and pro-oxidant adenine nucleotide translocators in the cytoplasmic or mitochondrial membrane of cells14.

Although human urinary excretion levels are usually below the exposure limits of the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and other worldwide environmental agencies, extensive laboratory studies have been done into the long-term effect on health due to the cumulative exposure in massive transfusion protocols and/or chronic exposure to DEHP and possible synergistic endocrine effects. DEHP undergoes metabolic degradation resulting in the formation of the monoester, mono(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (MEHP), and further oxidative forms15. MEHP has been shown to be carcinogenic via the activation of two nuclear transcription factors, PPARα and PPARγ, important to cell differentiation16. In addition, DEHP is a developmental and reproductive toxicant suspected of having endocrine disrupting or modulating effects17 and promoting inflammation18.

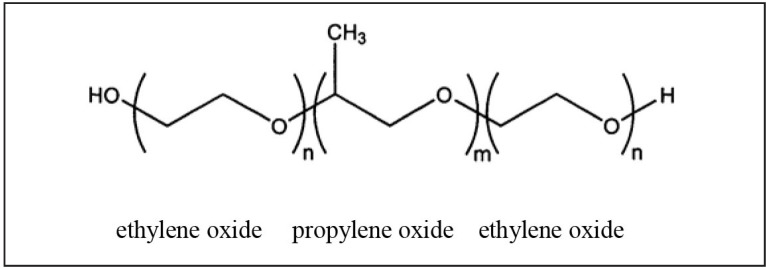

As a consequence of the harmful effects of DEHP, alternative methods to replace the protective effect of DEHP on haemolysis are warranted. A possible alternative is the use of a rheological agent with a favourable toxicity profile that mimics the beneficial effects of DEHP. Vepoloxamer is a highly purified form of the linear non-ionic amphiphilic copolymer poloxamer 188 (Figure 1). It is comprised of an internal hydrophobic polyoxypropylene chain flanked at either end by hydrophilic polyoxyethylene blocks. It exhibits rheologic, anti-thrombotic and cyto-protective properties in vitro and in vivo19–31. Its basic structure confers surface-active properties that enable the modulation of the biophysical properties of the cell membrane, including stability, hydration repair, flexibility, and adhesive properties, all of which serve crucial roles in biological responses. Vepoloxamer inhibits polymer-induced RBC aggregation and adhesion to endothelial cells32,33. Substantial research has demonstrated that vepoloxamer has cytoprotective and haemorheologic properties, and inhibits inflammatory processes and thrombosis19,22,29,34. The drug has been used in clinical trials of sickle cell patients with vaso-occlusive disease including a Phase III, double blind, placebo-controlled trial (registered as NCT01737814). In this last trial, although vepoloxamer was found not to reduce the duration of the vaso-occlusive disease in sickle cell patients when compared with a placebo control, the drug was found to be well tolerated and safe when administered in healthy and seriously ill humans.

Figure 1.

Chemical formula for vepoloxamer.

Vepoloxamer consists of repeated ethylene and propylene oxide groups. With n=80 and m=27, Vepoloxamer has a calculated molecular weight of 8,624 Daltons.

This study was designed to determine whether vepoloxamer could be used in RBC storage additive solutions to replace the effect of DEHP in reducing the haemolysis rate after long-term storage, and, if it proved to be protective, to explore the mechanisms involved in improving RBC viability in vitro.

Materials and methods

Blood collection and processing

Whole blood (500 mL ±10%) from 30 consenting donors aged 18–70 years old who fulfilled American Association of Blood Banks (AABB) and US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) criteria for donation (except for travel) was collected into a collection set with CPD anticoagulant (Code 4R3329, Fenwal Inc., Lake Zurich, IL, USA). Units were leucoreduced using the integral RS-2000 filter and stored in additive solution AS-1 within 8 hours of collection. Pools of two RBC suspensions from ABO identical donors aseptically split into five aliquots containing 95 mL of RBC suspension, and stored either DEHP/PVC or DEHP-free/ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) bags (Evolve EV-12+F-M12, Origen Biomedical, Austin, TX, USA), supplemented with or without 5 mL of GMP-grade vepoloxamer (Figure 1) or saline control and mixed before storage. Groups of paired analysis consisted of DEHP/PVC with no vepoloxamer (with added physiological saline solution, n=15), EVA with no vepoloxamer (with added physiological saline solution, n=15) and EVA with vepoloxamer at concentrations of 0.1 (n=9), 1 (n=15), 5 (n=15) or 7.89 (n=6) mg/mL in physiological saline solutions. RBC units were cold stored (1–6 °C) for 42 days.

Methods

For all aliquots, a complete blood count was analysed (Coulter Ac.T5 Diff CP analyzer, Coulter Corp., Miami, FL, USA). Spun haematocrit was determined using a microhaematocrit centrifuge, as previously described35. Supernatant haemoglobin and haemolysis rates were calculated as previously described36. pH, pO2, pCO2, extracellular glucose, sodium, potassium and lactate concentrations were measured using ABL805 FLEX Analyzer (Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Intracellular adenosine-5′-triphospate (ATP) levels were determined as previously described37. Osmotic fragility was analysed as previously described38 and deformability under shear stress conditions was assessed by ektacytometry at a maximum pressure of 60 Pa39. The above listed analyses were performed on days 28 and 42 of storage.

Also on day 42 of storage, oxidative stress was assessed by determination of the oxidised glutathione/reduced glutathione (GSSG/GSH) ratio40. Oxidised peroxiredoxin-2 (PRX2) levels were analysed by Western blot as previously described41, and band density analysed by the Image J software42 in relation to the loading control developed with anti-β-actin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and normalised to the values of the DEHP group. Eryptosis was analysed by determination of the percentage of cells with exposed extracellular phosphatidylserine (PS) residues as assessed by annexin-V binding and flow cytometry analysis. Briefly, RBCs were washed in annexin-V binding buffer containing (in mM) 125 NaCl, 10 HEPES, pH 7.4, and 5 CaCl2 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Erythrocytes were stained with annexin-FITC (BD Biosciences) at a 1:10 dilution. After 15 min, samples were washed with annexin-V binding buffer and measured by flow cytometry (FACSCalibur; Becton Dickinson). Annexin-V binding was analysed on a gate of appropriate forward and sideward scatter (logarithmic transformation) and annexin-V fluorescence intensity was measured in FL1.

Data are presented as average ±1 standard deviation (SD). Comparative statistical analysis was performed by ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

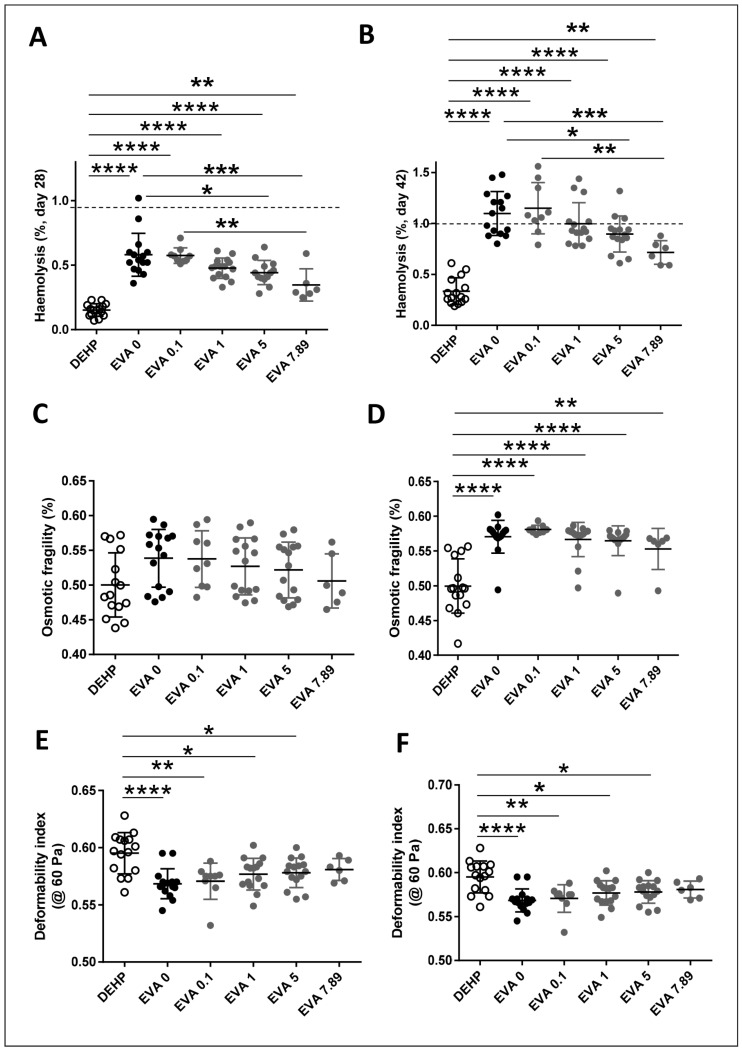

As expected, the absence of DEHP in EVA bags results in increased haemolysis by days 28 and 42 of storage (Figure 2A and B). Addition of vepoloxamer significantly reverses the increased haemolysis induced by removal of DEHP in EVA bags in a dose-dependent manner by day 28 and day 42 of storage (Figure 2A and B). Addition of vepoloxamer at the highest concentration tested (7.89 mg/mL) resulted in reduction of haemolysis at levels similar to the levels observed in the PVC/DEHP control. The haemolysis rate was inversely correlated with increasing concentrations of vepoloxamer (r2=0.27, p<0.001) indicating an association between both parameters. Similarly, the lack of a plateau phase suggests that the highest concentration of vepoloxamer may have not reached the peak of its biological effect on haemolysis prevention. A similar effect was observed by day 28 and especially by day 42 of storage on RBC osmotic fragility (Figure 2C and D) and deformability under shear stress at 60 Pa (Figure 2E and F), with a significant dose-dependent effect of vepoloxamer on the reversal of the increased osmotic fragility of day 42 stored RBC (Figure 2D) and shear-stress deformability of RBC stored in EVA bags (Figure 2E and F). These changes may have resulted in a reversal of the eryptosis of RBC when stored in EVA, as assessed by analysis of PS exposure through the determination of the percentage of RBC with the ability to bind annexin-V in units containing increasing concentrations of vepoloxamer by day 42 of storage (Figure 3A), with a direct correlation between haemolysis and PS exposure (r2=0.42; p<0.001). These results indicate that vepoloxamer prevents the RBC storage lesion associated with replacement of PVC/DEHP for EVA as constituent of the storage bags and are consistent with the hypothesised role of vepoloxamer as an RBC membrane intercalator that interferes with the process of eryptosis and in vitro haemolysis.

Figure 2.

Addition of vepoloxamer results in a dose-dependent reduction in haemolysis and fragility of red blood cells (RBC) stored in ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) bags.

(A and B) Haemolysis. (C and D) Osmotic fragility. (E and F) Deformability index (ektacytometry at 60 Pa). *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001 (ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction). DEHP: polyvinyl chloride bag with di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) plasticiser.

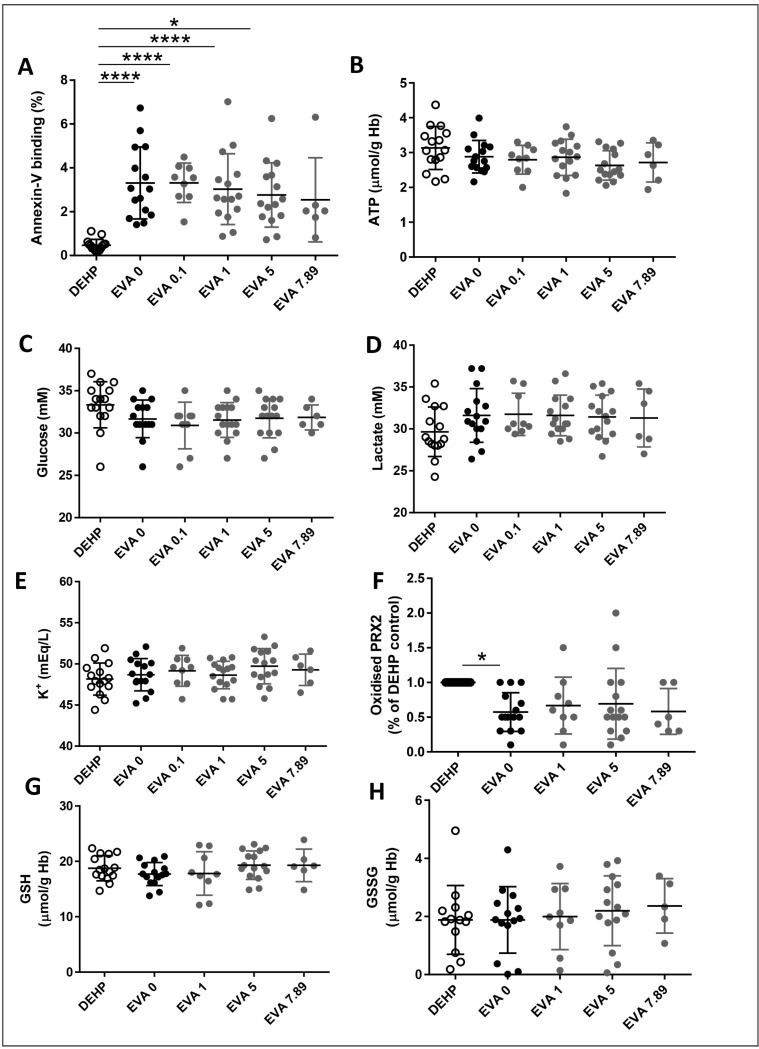

Figure 3.

Addition of vepoloxamer results in a dose-dependent reduction of eryptosis with no changes in glycolytic flux, potassium leakage or redox potential by day 42 of storage.

(A) Percentage of red blood cell (RBC) binding annexin-V. (B) Intracellular adenosine-5′-triphospate (ATP) concentration levels. Extracellular concentration of (C) glucose and (D) lactate. (E) Extracellular potassium concentration. (F) Intracellular level of oxidised PRX2. Intracellular levels of (G) reduced glutathione (GSH) and (H) oxidised glutathione (GSSG). * p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001 (ANOVA test with Bonferroni correction). DEHP: polyvinyl chloride bag with di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) plasticiser.

Interestingly, the amelioration of eryptosis and in vitro haemolysis is not associated with modifications in the concentrations of different biochemical parameters associated with metabolic, transmembrane potential or redox stress. There were no significant changes in ATP (Figure 3B), glycolytic flux as assessed by changes in the extracellular concentrations of glucose (Figure 3C) or lactate (Figure 3D), or potassium leakage (Figure 3E). Similarly, despite a modest reduction in oxidative stress of EVA-stored RBC compared with DEHP/EVA stored bags (Figure 3F), vepoloxamer addition did not result in any changes in the intracellular levels of oxidised peroxiredoxin-2 (PRX2) (Figure 3F) or of the intracellular levels of GSSG (Figure 3G) or in the overall intracellular concentration of the GSH (Figure 3H).

Discussion

In this study, we analysed for the first time the possibility of replacing the effect of the DEHP plasticiser used in PVC bags by adding vepoloxamer into malleable EVA bags by adding vepoloxamer at increasing concentrations. Our data support the concept that vepoloxamer does prevent the RBC storage lesion in vitro as it reduces the haemolysis, eryptosis and osmotic fragility, and increases the erythrocyte deformability under significant shear stress of up to 60 Pa. This effect seems to be unrelated to modifications in the energy production, glycolytic flux, cat ion exchange activity or redox potential, suggesting that its actions occur by direct interactions of the polymer with lipids and lipoproteins on the red cell membrane leaflets.

Toth et al.32 demonstrated that unpurified vepoloxamer, at concentrations of 0.5–5 mg/mL, inhibited both the extent and strength of RBC aggregation in a dose-dependent manner in the presence of aggregating concentrations of Dextran-70. Vepoloxamer at a concentration of 5 mg/mL was more effective in improving the rheology of younger, less dense cells. Based upon the depletion model for polymer-induced aggregation, these authors suggest that vepoloxamer acts by penetrating the depletion layer near the glycocalyx, thereby reducing the osmotic gradient between the intercellular gap and the suspending medium. Sandor et al.33 also demonstrated that unpurified poloxamer 188 significantly reduces blood viscosity, and RBC aggregation and adhesion to endothelial cells, possibly by acting as an intercalating agent in cell membranes. Our results further support the effect of vepoloxamer on modifications of the RBC membrane that result in stabilisation as assessed by significant reduction of their osmotic fragility and increase in their deformability upon shear stress.

Conclusions

Vepoloxamer is able to significantly rescue the increased haemolysis induced by the absence of the commonly used plasticiser DEHP in a concentration-dependent fashion. While the biochemical/biophysical mechanism of this restoration remains unclear, the improved osmotic fragility and shear-stress deformability index strongly suggests that vepoloxamer may act as an intercalating agent with the ability to increase the RBC membranes flexibility and fitness to challenging storage-dependent rheological conditions. These results provide evidence that the rheological agent vepoloxamer may provide an alternative to the current use of potentially harmful plasticisers like DEHP for long-term RBC storage.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Theodosia Kalfa (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center) for providing the ektacytometry analysis of red blood cell deformability.

Footnotes

Authorship contributions

JAC designed experiments, analysed data and wrote the manuscript. NR analysed data and supervised the study. SN and SEH performed experiments. RME and DSMc-K designed experiments. All Authors read the manuscript and contributed to the finalisation of the manuscript.

Disclosure of conflicts of interest

RME and DSMc-K are employees of Mast Therapeutics Inc. Mast Therapeutics Inc. provided study materials and funds to conduct this study. The other Authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Heudorf U, Mersch-Sundermann V, Angerer J. Phthalates: toxicology and exposure. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2007;210:623–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly-Identified Health Risks. Preliminary report on the safety of medical devices containing DEHP-plasticized PVC or other plasticizers on neonates and other groups possibly at risk. Health & Consumer Protection, European Commission; 2007. [Accessed on 17/01/2017]. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_risk/committees/04_scenihr/docs/scenihr_o_008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Food and Drug Administration, Health CfDaR. Safety assessment of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) released from PVC medical devices. 2002. [Accessed on 17/01/2017]. Available at: DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/UCM080457.pdf.

- 4.D’Alessandro A, Nemkov T, Hansen KC. Rapid detection of DEHP in packed red blood cells stored under European and US standard conditions. Blood Transfus. 2016;14:140–4. doi: 10.2450/2015.0210-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jaeger RJ, Rubin RJ. Plasticizers from plastic devices extraction, metabolism, and accumulation by biological systems. Science. 1970;170:460–2. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3956.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaeger RJ, Rubin RJ. Migration of a phthalate ester plasticizer from polyvinyl chloride blood bags into stored human blood and its localization in human tissues. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:1114–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197211302872203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasakawa S, Mitomi Y. Di-2-ethylhexylphthalate (DEHP) content of blood or blood components stored in plastic bags. Vox Sang. 1978;34:81–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1978.tb03727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Contreras TJ, Sheibley RH, Valeri CR. Accumulation of DI-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) in whole blood, platelet concentrates, and platelet-poor plasma. Transfusion. 1974;14:34–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.1974.tb04481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue K, Kawaguchi M, Yamanaka R, et al. Evaluation and analysis of exposure levels of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate from blood bags. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;358:159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2005.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jaeger RJ, Rubin RJ. Plasticisers from P.V.C. Lancet. 1970;2:778. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(70)90261-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.AuBuchon JP, Estep TN, Davey RJ. The effect of the plasticizer di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate on the survival of stored RBCs. Blood. 1988;71:448–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estep TN, Pedersen RA, Miller TJ, et al. Characterization of erythrocyte quality during the refrigerated storage of whole blood containing di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate. Blood. 1984;64:1270–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rock G, Tocchi M, Ganz PR, et al. Incorporation of plasticizer into red cells during storage. Transfusion. 1984;24:493–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1984.24685066808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kora S, Sado M, Koike H, et al. Protective effect of the plasticizer di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate against damage of the mitochondrial membrane induced by calcium: possible participation of the adenine nucleotide translocator. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;985:286–92. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(89)90414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services. Toxicological profile for di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate. 2002. [Accessed on 17/01/2017]. Available at: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/toxprofiles/tp9.pdf.

- 16.Hurst CH, Waxman DJ. Activation of PPARalpha and PPARgamma by environmental phthalate monoesters. Toxicol Sci. 2003;74:297–308. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfg145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeshita A, Inagaki K, Igarashi-Migitaka J, et al. The endocrine disrupting chemical, diethylhexyl phthalate, activates MDR1 gene expression in human colon cancer LS174T cells. J Endocrinol. 2006;190:897–902. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rael LT, Bar-Or R, Ambruso DR, et al. Phthalate esters used as plasticizers in packed red blood cell storage bags may lead to progressive toxin exposure and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2009;2:166–71. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.3.8608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colbassani HJ, Barrow DL, Sweeney KM, et al. Modification of acute focal ischemia in rabbits by poloxamer 188. Stroke. 1989;20:1241–6. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.9.1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hunter RL, Papadea C, Gallagher CJ, et al. Increased whole blood viscosity during coronary artery bypass surgery. Studies to evaluate the effects of soluble fibrin and poloxamer 188. Thromb Haemost. 1990;63:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Justicz AG, Farnsworth WV, Soberman MS, et al. Reduction of myocardial infarct size by poloxamer 188 and mannitol in a canine model. Am Heart J. 1991;122:671–80. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90510-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mayer DC, Strada SJ, Hoff C, et al. Effects of poloxamer 188 in a rabbit model of hemorrhagic shock. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1994;24:302–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter RL, Jagannath C, Tinkley A, et al. Enhancement of antibiotic susceptibility and suppression of Mycobacterium avium complex growth by poloxamer 331. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:435–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jagannath C, Allaudeen HS, Hunter RL. Activities of poloxamer CRL8131 against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vitro and in vivo. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:1349–54. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.6.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jagannath C, Emanuele MR, Hunter RL. Activities of poloxamer CRL-1072 against Mycobacterium avium in macrophage culture and in mice. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2898–903. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.12.2898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jagannath C, Emanuele MR, Hunter RL. Activity of poloxamer CRL-1072 against drug-sensitive and resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in macrophages and in mice. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2000;15:55–63. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(00)00118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jagannath C, Sepulveda E, Actor JK, et al. Effect of poloxamer CRL-1072 on drug uptake and nitric-oxide-mediated killing of Mycobacterium avium by macrophages. Immunopharmacology. 2000;48:185–97. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00203-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Dadswell CM, et al. Causative factors behind poloxamer 188 (Pluronic F68, Flocor)-induced complement activation in human sera. A protective role against poloxamer-mediated complement activation by elevated serum lipoprotein levels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1689:103–13. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harting MT, Jimenez F, Kozar RA, et al. Effects of poloxamer 188 on human PMN cells. Surgery. 2008;144:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang R, Hunter RL, Gonzalez EA, et al. Poloxamer 188 prolongs survival of hypotensive resuscitation and decreases vital tissue injury after full resuscitation. Shock. 2009;32:442–50. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31819e13b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter RL, Luo AZ, Zhang R, et al. Poloxamer 188 inhibition of ischemia/reperfusion injury: evidence for a novel anti-adhesive mechanism. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2010;40:115–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toth K, Wenby RB, Meiselman HJ. Inhibition of polymer-induced red blood cell aggregation by poloxamer 188. Biorheology. 2000;37:301–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sandor B, Marin M, Lapoumeroulie C, et al. Effects of Poloxamer 188 on red blood cell membrane properties in sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2016;173:145–9. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Armstrong JK, Meiselman HJ, Fisher TC. Inhibition of red blood cell-induced platelet aggregation in whole blood by a nonionic surfactant, poloxamer 188 (RheothRx injection) Thromb Res. 1995;79:437–50. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(95)00134-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.AuBuchon JP, Cancelas JA, Herschel L, et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of LEUKOSEP HRC-600-C leukoreduction filtration system for red cells. Transfusion. 2006;46:1311–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bandarenko N, Cancelas J, Snyder EL, et al. Successful in vivo recovery and extended storage of additive solution (AS)-5 red blood cells after deglycerolization and resuspension in AS-3 for 15 days with an automated closed system. Transfusion. 2007;47:680–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2007.01171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cancelas JA, Rugg N, Fletcher D, et al. In vivo viability of stored red blood cells derived from riboflavin plus ultraviolet light-treated whole blood. Transfusion. 2011;51:1460–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.03027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Meer PF, Cancelas JA, Vassallo RR, et al. Evaluation of the overnight hold of whole blood at room temperature, before component processing: platelets (PLTs) from PLT-rich plasma. Transfusion. 2011;51:45S–49S. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02962.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalfa TA, Pushkaran S, Mohandas N, et al. Rac GTPases regulate the morphology and deformability of the erythrocyte cytoskeleton. Blood. 2006;108:3637–45. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-005942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pei S, Minhajuddin M, Callahan KP, et al. Targeting aberrant glutathione metabolism to eradicate human acute myelogenous leukemia cells. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:33542–58. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.511170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Neill JS, Reddy AB. Circadian clocks in human red blood cells. Nature. 2011;469:498–503. doi: 10.1038/nature09702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nature Methods. 2012;9:671–5. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]