Abstract

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is one of the highly aggressive malignancies in the United States. It has been shown that multiple signaling pathways are involved in the pathogenesis of PC, such as JNK, PI3K/AKT, Rho GTPase, Hedgehog (Hh) and Skp2. In recent years, accumulated evidence has demonstrated that Notch signaling pathway plays critical roles in the development and progression of PC. Therefore, in this review we discuss the recent literature regarding the function and regulation of Notch in the pathogenesis of PC. Moreover, we describe that Notch signaling pathway could be down-regulated by its inhibitors or natural compounds, which could be a novel approach for the treatment of PC patients.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, notch, cellular signaling, therapy, target

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is a highly aggressive malignancy and ranks the fourth leading cause of cancer related death in the United States [1]. In China, PC belongs to one of the ten most common cancers for men, and the incidence and the mortality of PC are increased in recent years [2]. This high mortality is partly due to the absence of specific symptoms and signs, and the lack of early detection tests for PC, as well as the lack of effective chemotherapies [3]. Although the molecular mechanisms of PC development remain largely unclear, many factors have been reported to be associated with increased incidence of PC [4]. For example, a history of diabetes or chronic pancreatitis, chronic cirrhosis, a family history of PC, a high-fat and high-cholesterol diet, tobacco smoking, alcohol and coffee intake, use of aspirin and specific blood type have been found to contribute to PC development [5]. In recent years, studies have shown that multiple cellular signaling pathways such as JNK [6], PI3K/AKT [7], nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB) [8], Hedgehog [9], and Skp2 [10] are believed to play critical roles in the aggressive pathological progression of PC. It is important to note that the exact mechanisms by which PC develops and progresses still remain poorly understood. However, robust evidence has been accumulated to suggest that Notch plays an important role in the development of PC [11-14]. Therefore, in this review article, we will focus our discussion on the role of Notch in the development and progression of PC, and further summarize potential approaches by which Notch could be inhibited.

Notch signaling pathway

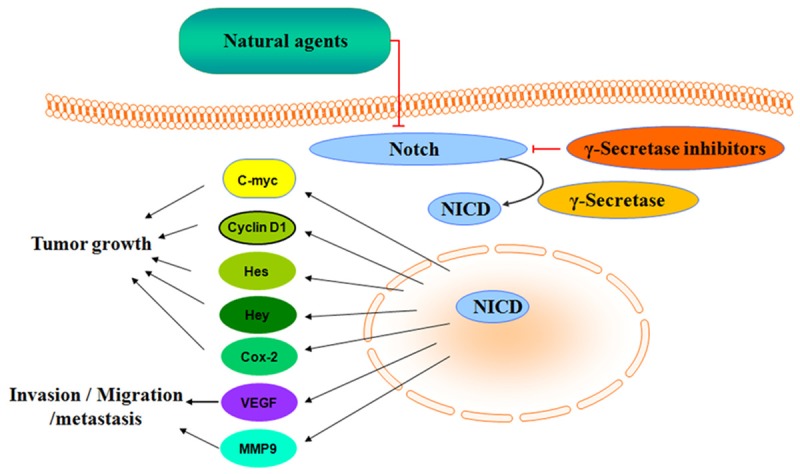

It has been well documented that the Notch signaling pathway is critical for cell proliferation, differentiation, development and homeostasis [15]. It is known that mammals express four transmembrane Notch receptors (Notch-1, Notch-2, Notch-3 and Notch-4) and five canonical transmembrane ligands (Delta-like 1, Delta-like 3 and Delta-like 4, Jagged-1 and Jagged-2) [16]. Notch signaling pathway will be activated after Notch-ligand binding and three consecutive proteolytic cleavages by multiple enzyme complexes including γ-secretase complex [17]. This produces an active fragment, NICD (Notch intracellular domain), which enters the nucleus and binds to CSL, and displaces co-repressors from CSL, and subsequently recruits a co-activator complex containing mastermind, p300, and other co-activators, leading to the activation of Notch target genes [18]. So far, many Notch target genes have been identified such as Hes (hairy enhance of split) family, Hey family, Akt, cyclin D1, c-myc, COX-2 (cyclooxygenase-2), ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase), MMP-9 (matrix metalloproteinase-9), mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), NF-κB, p21, p27, p53 and VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) [15]. Since these target genes are critically involved in tumorigenesis [19], Notch signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in the development and progression of human cancers via regulating its target genes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagram of Notch signaling. Notch signaling pathway plays a pivotal role in the development and progression of PC via regulating its target genes. γ-secretase inhibitors and natural agents could be inhibitors of Notch pathway in PC cells.

The role of notch in the development and progression of pancreatic cancer

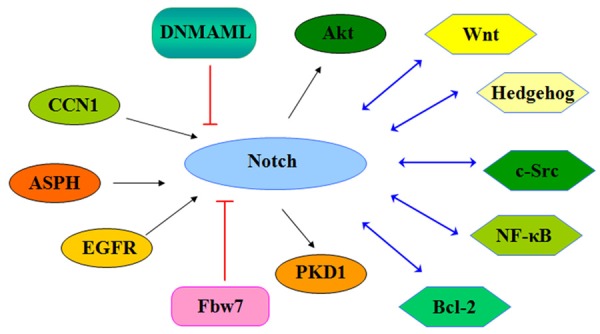

It is noteworthy that the Notch signaling pathway exerts both oncogenic and tumor suppressive functions, depending on the cellular context [20]. For example, one study has shown that Notch-1 has an oncosuppressive function in skin cancer [21]. Another study has demonstrated that Notch1 suppresses PanIN (Pancreatic Intraepithelial Neoplasias), the proposed precursor lesions of PC formation in a mouse model of PC [22]. More evidence suggests that Notch plays important oncogenic roles in pancreatic tumorigenesis. For example, it has been reported that Notch can promote PanINs [23]. Many literatures also strongly suggested that increased expression of Notch is detected in PC cells and tissues. Moreover, reactivation of Notch signaling is observed in early PC pathogenesis and persists throughout the progression of the disease [24-28], suggesting that Notch could be useful as a prognostic biomarker. However, the molecular mechanism(s) by which Notch induces PC growth has not been fully elucidated. However, multiple signaling pathways, such as MEK/ERK [24], plasma growth factor receptor-c-Src [29], Hedgehog [30], TGF-β (transforming growth factor-beta) [31], and Wnt [32] signaling have been reported to crosstalk with Notch in PC, and so it is believed that the crosstalk between Notch and these signaling pathways may play critical roles in pancreatic tumorigenesis. In the following sections, we will discuss the recent advances in our understanding of the role of Notch in PC progression. We will also summarize the results of emerging studies on Notch, including the upstream regulators and downstream effectors of this protein, as well as its implication in human PC.

Upstream regulators of notch in PC

Little is known regarding the upstream regulators of Notch in PC. Several groups have found that some genes can regulate Notch expression. For instance, EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) can regulate Notch-1 expression and EGFR-mediated Notch-1 activation leads to the up-regulating MMP-9 and VEGF expression, and stimulating cell invasion and metastasis in PC cells [29]. Notch was also proved as a target for CCN1 regulation that provides signals that support tumorigenic activities [33]. Additionally, Tremblay et al. reported that activation of the MEK/ERK pathway promotes Notch signaling [24]. More recently, it has been found that overexpression of ASPH (Aspartate β-hydroxylase) activates Notch by promoting cleavage of Notch1 ICN to liberate the C-terminal ICN and subsequently upregulates a number of downstream Notch responsive genes in PC cells [34]. DNMAML (Dominant-Negative form of Mastermind-like1) expression successfully inhibited Notch signaling in the pancreas in vivo [23], leading to degradation of nuclear Notch1 thereby inducing PC cell death [35]. The mechanisms by which these upstream genes regulate Notch are discussed in the following paragraphs.

EGFR regulates notch in PC

EGFR is a member of the ErbB family of receptors and has tyrosine kinase activity and it is overexpressed in PC [36]. EGFR could dimerize with other members of the EGFR family as a homodimer or heterodimer, after ligand binding. Then, EGFR is activated by auto-phosphorylated or trans-phosphorylated at specific tyrosine residues, then multiple downstream signaling pathways, including phosphatidylinositol 3’-kinase and AKT, ERK, and the Notch pathway are activated, finally, leading to increased cellular proliferation and prevention of apoptosis [37,38]. EGFR over-expression is supposed to confer a poor survival, relating to a more advanced stage and the presence of metastases in PC. Consequently, inhibition of the EGFR signaling pathway is a tempting therapeutic target. The relationship between Notch and EGFR is mostly antagonistic, which may in part be based on the phosphorylation of the Notch signal transducer Suppressor of Hairless, a transcription factor that together with several cofactors regulates the expression of Notch target genes by MAPK (Mitogen-activated protein kinase) [39].

We have found that ERRP (EGFR-related peptide) inhibited cell growth of PC cells by attenuating EGFR activation in vitro and in vivo [40,41], then, we strongly proved that ERRP down-regulate Notch-1 and its downstream target genes which are mechanistically linked to apoptotic processes in PC [38]. That is ERRP inhibited the activation of EGFR and also reduced the activity of Notch-1 signaling.

CCN1 regulates notch in PC

CCN1, formerly known as cyr61, belongs to the Cyr61-CTGF-Nov (CCN) family and is a secreted protein that functions in a paracrine and/or autocrine manner [42,43]. CCN1’s functions include but not limited to angiogenesis, cell adhesion, migration and cytoprotection [43-46]. It is abnormal expression in a variety of cancers including PC [33]. Haque et al. showed that CCN1 mRNA and protein expression were elevated in most of PC specimens and pancreatic cancer cell lines, and silencing CCN1 inhibited cell migration, EMT and tumor growth in nude mice [47].

CCN1 is a potent regulator of Shh (sonic hedgehog) pathway via Notch-1. CCN1 activity was mediated in part through altering proteosome activity [33]. It has been shown that CCN1 impacts both the Shh and Notch pathways [48]. CCN1 acts, at least in part, by altering proteosome activity. Neutralizing anti-integrin αv or anti-integrin β3 antibodies markedly blocked CCN1-induced activation of Notch-1 and Shh in PC cells, emphasizing the importance of these integrins in CCN1-mediated activity. These results suggest that CCN1 may be an ideal target for treating PC.

MEK/ERK regulates notch in PC

It is well documented that MEK/ERK signaling is directly involved in the prevention of apoptosis [49]. The MEK/ERK pathway has been shown to play a pivotal role in controlling cell growth, radioresistance and differentiative signals [50]. MEK/ERK pathway plays a prominent role in maintaining the stem-like phenotype of rhabdomyosarcoma cells [51]. Abnormal activation of the MEK/ERK signaling pathway is tightly associated with tumorigenesis including PC [52].

Tremblay et al. founded that MEK/ERK signaling pathway is efficient to, immediately after Notch1 cleavage, directly influence NIC1 (Notch1 intracellular domain) transcriptional function [24]. They suggested that the MEK/ERK pathway promoted expression of Notch target genes, therefore influencing Notch signal strength by promoting the assembly of a functional NIC1 transcriptional unit with CSL and MAML1 (MASTERMIND-LIKE 1) in PC. However, further studies are required to delineate the precise mechanisms by which the MEK/ERK pathway promotes Notch signaling.

ASPH regulates notch in PC

Aspartate β-hydroxylase (ASPH) is an 86 KD Type II transmembrane protein. It is also a member of the α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase family [34,53]. ASPH catalyzes the β-hydroxylation of aspartyl and asparaginyl residues located in the EGF-like repeats of various proteins including Notch, Jagged and Delta-like [54]. ASPH is expressed in many organs during embryogenesis, but has very low or negligible expression in adult tissues [55]. Then, it re-emerges in tumors of pancreas and lung [34,56], suggesting it may be an oncogene involved in the transformation of normal cells to a malignant phenotype [57]. ASPH could promote tumor growth and cell migration and invasion [58,59]. ASPH may play an important role in PC pathogenesis [34].

Notch receptors contain 36 EGF-like repeats in the extracellular domain, which are the substrates of ASPH β-hydroxylase. Notch signaling pathway can be activated by ASPH upregulation to promote tumor cell migration, invasion and metastases [58,60]. Dong et al. reported that ASPH may promote the interactions of the Notch receptors with their ligands (such as Jagged and Delta-like) [34]. It is suggested that enhanced Notch receptor-ligand interaction leads to the generation of activated Notch1 ICN followed by upregulation of downstream target genes.

DNMAML regulates notch in PC

DNMAML contains amino acids 13-74 of MAML1, which binds the Notch-CSL/RBP-J complex, but lacks the MAML1 sequences needed to recruit transcriptional coactivators [61]. Tu et al. supposed that DNMAML is a pan-Notch inhibitor, blocking signaling from all four Notch receptors [62]. DNMAML expression was previously shown to lead to both cell proliferation and invasion [63]. Thomas et al. found that DNMAML expression efficiently inhibits epithelial Notch signaling and delays PanIN formation [23].

FBW7 regulates notch in PC

FBW7 (F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7), also known as Fbxw7, is the F-box protein subunit of a Skp1-Cul1-F-box protein (SCF)-type ubiquitin ligase complex. FBW7 contains 3 isoforms (FBW7α, FBW7β, and FBW7γ), and they are differently regulated in subtract recognition [64]. Besides, FBW7 activity is controlled at different levels, resulting in regulation of the abundance and activity of its substrates in a variety of human solid tumors, including PC [65]. FBW7 has been found to be related to numerous cellular processes such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, cell cycle and differentiation [66-68]. Furthermore, FBW7 is considered as a tumor suppressor protein for that it targets multiple well-known oncoproteins including Notch-1 by ubiquitination-mediated destruction [35,69]. It is well documented that FBW7 binds to phosphorylated Notch 1C and mediates its ubiquitination and then rapid degradation [70]. Furthermore, FBW7 regulates Notch1 downstream signaling pathways through ubiquitin ligase-mediated degradation [71].

We observed that accumulation of FBW7 can lead to down-regulation of Notch1 and related pathways (Hes-1, C-Myc and VEGF) in PC cells which was correlated with growth inhibition, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of PC in vitro and in vivo [35]. More importantly, we found that miR-223 governs gemcitabine-resistant (GR)-induced epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in part due to down-regulation of its target FBW7 and subsequent upregulation of Notch-1 in PC [72].

Downstream effectors of notch in pancreatic cancer

Studies have demonstrated that Notch regulates a variety of cellular processes including cell cycle progression, cell proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, migration, invasion, and survival, all of which are related to cancer development and progression. This is mainly achieved through directly promoting the degradation of Notch downstream targets. Here, we mainly focus on discussing the recent advances in the understanding of the role of Notch in PC progression.

Notch regulates Akt in PC

Serine/threonine protein kinase Akt named protein kinase B (PKB), the virus oncogenes V-akt homologue. The function of the Akt involves nutrient metabolism, cell survival and cell growth, cell apoptosis, and cell cycle regulation [73-76]. Akt has three isoforms Akt1, Akt2 and Akt3 (or PKBα/β/γ respectively) [77]. Aberrant expression of Akt leads to many diseases such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular and neurological diseases [78]. Akt is found to be activated in 59% of tumors [13]. It is well known that Akt could be a central node in signaling pathways consisting of many downstream components, such as mTOR [79].

Li et al. found that Notch-1 activates Akt in breast cancer [80]. Vo et al. discovered that Notch modulates the Akt pathway through regulation of PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homologue) phosphorylation [13]. Moreover, the regulation is dependent on RhoA, a member of the Rho family of small GTPases which is required for Rock1 activation [81]. The Notch-dependent increase in PTEN phosphorylation is inhibited by Rock1 inhibitor, suggesting that Notch regulates PTEN through the RhoA/Rock1 pathway in PC. Therefore, targeting both pathways will lead to a greater efficacy in the treatment of patients with PC.

Notch regulates PKD1 in PC

Protein Kinase D family members are serine/threonine kinases that consists of three isoforms: PKD1/PKCµ, PKD2 and PKD3/PKCv [82]. PKDs effect on diverse biological processes such as protein transport, cell migration, proliferation and apoptosis, which are characteristics in the stepwise pathogenesis of neoplasia. PKDs have distinct impact on these functions. PKD1 was the first isoform identified and is the most widely studied [83]. PKD1 blocks EMT and cell migration [84], and it was overexpressed in PC patient samples [85]. In PC cell lines PKD1 contributes to cell proliferation and cell survival [86,87]. Furthermore, it was shown that inhibition of PKD1 decreases orthotopic growth of PC cell lines in mice [86].

Liou et al. show that PKD1 signaling can contribute to very early events that alter pancreas cellular plasticity. Their results show that PKD1 is necessary to mediate TGFα- and active Kras-induced reprogramming of pancreatic acinar cells to a duct-like phenotype that can give rise to PanIN lesions [88]. They identified that Notch signaling pathway activates the TGFα-Kras-PKD1 [88].

Notch cross-talks with other major signaling pathways in PC

Notch has been reported to cross-talk with other pathways, such as Bcl-2, and NF-κB [89,90]. Thus, cross-talks between Notch and other pathways could play pivotal roles in pancreatic tumorigenesis.

The cross-talk between notch and Bcl-2 in PC

B-cell leukemia/lymphoma-2 (Bcl-2) and its family members were overexpressed in PC [91,92]. Bcl-2 is the strongest apoptosis inhibitor among all known cell proteins [93], and it includes three subgroups of proteins. Defects in apoptosis are now considered to be a hallmark of most cancers [94]. Bcl-2 family proteins decide mitochondrial involvement in cell death cascades, modulating commitment to apoptosis to diverse stimuli [95]. It has been well documented that Bcl-2 functions through heterodimerization with proapoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family to prevent mitochondrial pore formation and prevent cytochrome c release and initiation of apoptosis [89,96]. A number of studies have shown that activated Notch can regulate expression of Bcl-2 [97,98], suggesting that Bcl-2 is downstream of Notch inhibition. Additionally, overexpression of Bcl2 can increase Notch-1. However, down-regulation of Bcl-2 can inhibit the Notch-1 expression in PC cells [89]. We found that the inactivation of Bcl-2 down-regulated the Notch-1 activity, resulting in the inhibition of the growth of PC cells in vitro and in vivo [89].

The cross-talk between notch and NF-κB in PC

The NF-κB family includes homo- or heterodimers formed by p50, p65 (RelA), c-Rel, p52, and RelB [99,100]. NF-κB plays an important role in the control of cell growth, differentiation, apoptosis and inflammation by mediating survival signals [101,102]. NF-κB and Notch pathways are activated in many types of cancers including PC [103,104]. Numerous reports have described regulation of NF-κB by Notch and vice versa through different, context-dependent mechanisms [105]. It is well documented that transcriptional regulation of NF-κB pathway members by Notch and transcriptional regulation of Notch pathway members by NF-κB are physical interaction between Notch and NF-κB [105]. Maniati et al. supposed that the interaction between NF-κB and Notch signaling and a coordinated downregulation of PPARγacted as a forward feedback loop that sustains expression of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by the transformed cells in PC, which highlight the requirement for inflammatory signaling pathways in the development of PC [90].

The cross-talk between notch and c-Src in PC

C-Src is a non-receptor tyrosine kinase product of the proto-oncogene c-Src [106], which has been shown to exert as a target of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) in transactivation of growth factor receptors such as EGFR [107]. c-Src also takes part in cytokine-activated transactivation of growth factor receptors such as EGFR in several cell types [108]. More and more evidence suggests Src as an important determinant of tumorigenesis, invasion, and metastasis [109]. c-Src is overexpressed in over 70% of PC cell lines, and Src kinase activity is often elevated [106].

Some studies have demonstrated colocalization of Notch and c-Src proteins in PC cells, where Src is required for proteolytic activation of Notch [29], and of Notch and the T-cell-specific Src family member Lck in T cells [110]. Ho et al. revealed a functional relationship between the two genes that is Notch-Src accesses JNK in a significantly different fashion than Notch-Mef2 (Myocyte enhancer factor 2) [111]. Ma et al. indicated that Notch-1 and c-Src proteins are physically associated and that this kind of association mediates Notch-1 processing and activation [29].

The cross-talk between notch and hedgehog in PC

The hedgehog (Hh) signaling pathway is a critical embryological signaling pathway, both during development and in adult tissues. The pathway is regulated by two twelve-pass transmembrane receptors, Patched1 (Ptch1) and Patched2 (Ptch2), which are localized to the primary cilium [112]. There are three homologous Hh ligands: Sonic hedgehog (Shh), Indian hedgehog (Ihh) and Desert Hedgehog (Dhh) exist in most vertebrate species. Each homologous has different expression patterns and functions, which probably helped promote the increasing complexity of vertebrates and their successful diversification [113]. It has been discovered that many cancers contain abnormal Hedgehog signaling activation which is associate with 1/3 of cancer-related deaths. Hedgehog signaling pathway is an ideal target for chemotherapeutic development [114]. Gli1, a downstream transcription factor of the Hedgehog signaling pathway, is overexpressed in many cancers and is supposed to play a role in the development and progression of metastatic diseases [115]. Aberrant Hedgehog/GLI signaling pathway activity has been related to growth and progression in many types of cancers including PC [116,117].

Notch and Hedgehog signaling have been implicated in the survival of cancer stem cells (CSC), suggesting that both pathways will need to be targeted simultaneously when we aim to eradicate some kinds of cancer in patients [118]. Schreck et al. found that direct upregulation of the Hedgehog pathway through a novel cross talk mechanism, which is Notch like directly suppress Hedgehog via Hes1 mediated inhibition of Gli1 transcription [119]. Vice versa, Hedgehog pathway components Gli1 and Gli2 are able to positively regulate Hes1 independently of Notch [120,121]. Targeting both pathways simultaneously may be more effective at eliminating cancer cells. Downregulation of Notch leads to the cell growth inhibition and apoptosis of PC cells, whereas Hedgehog inhibition will contribute to enhanced delivery of drugs to the tumors. Both pathway inhibitors seem to have synergistic effects for therapeutics for PC [122].

The cross-talk between notch and wnt in PC

The Wnt signal pathway is an important embryonic signaling pathway that is required for proliferation, morphogenesis and differentiation of several organs, including the pancreas [123]. Wnt ligands bind to receptors of the Frizzled (FZD)/low-density lipoprotein receptor related protein then inactivate of a complex of cytoplasmic proteins that promote the proteasomal degradation of β-catenin, resulting in its cytoplasmic accumulation and nuclear localization and subsequent transcriptional regulation of target gene [124-126]. Wnt signaling regulates many aspects of pancreatic biology, and its activity is gradually increased during pancreatic carcinogenesis. The accumulation of β-catenin and activation of Wnt target genes have been observed in PanINs and PC [127,128].

Notch and Wnt signaling are both pivotal pathways that control the proliferation and differentiation of stem/progenitor cells [129]. In the early pancreatic lineage commitment, there is a crosstalk between Notch and Wnt signaling. Notch pathway promotes the lineage commitment and differentiation of pancreatic progenitors, whereas Wnt signaling maintains the stem cell state [130-133]. Wnt pathway regulates Notch signaling by the negative effect of Wnt on the Dishevelled 2 (Dvl2)-mediated GSK3β activity. GSK3β stabilizes the Notch-IC by binding and phosphorylating Notch-IC in the embryonic fibroblasts and N2a cells [134], and GSK-3β inhibition leads to the degradation of Notch-IC mediated by the proteasome [133]. Furthermore, Wnt signaling inhibits Notch activity through Pygopus2 to promote self-renewal and to prevent the premature differentiation of mammary stem cells [135]. On the other hand, Notch has been demonstrated to directly bind to β-catenin to inhibit its function by promoting β-catenin lysosomal sequestration and degradation in embryonic stem cells and colon cancer cells [136]. Notch and Wnt pathways appear to be interlinked in that Notch signaling functions as a negative regulator β-catenin dependent signaling both in pancreas organogenesis and oncogenesis [32].

Notch inhibition is a novel strategy for PC treatment

Since Notch signaling pathway is involved in tumor cell cycle regulation, cell growth, apoptosis, migration, and metastasis and its cross-talk with many signaling pathways in human cancers including PC, Notch has emerged as an attractive pharmacological target for the development of novel cancer therapy. Due to that Notch signaling is activated via the activity of γ-secretase, γ-secretase inhibitors (GSIs) could be useful for cancer therapy [16,137]. Indeed, emerging evidence has suggested that several forms of GSIs inhibited tumor cell growth, migration and invasion in various human cancers including PC [138]. For example, the inhibition of Notch activity by GSIs retarded tumor development in a murine model of PC [138]. Notably, GSI can block EMT, migration and invasion in PC cells, and suppress pancreatic CSCs in a xenograft mouse model [139]. Although GSI has shown the antitumor activity in human cancer, GSIs exhibits multiple side-effects. For instance, GSIs could block the cleavage of all four Notch receptors and multiple other γ-secretase substrates, which could be important for normal cell survival [138]. Additionally, GSIs has unwanted cytotoxicity in the gastrointestinal tract [138].

To overcome the limitations of GSIs, several studies have used less toxic alternative therapies such as Quinomycin [140]. or other natural compounds, which are typically non-toxic to human cells, to inhibit Notch signaling pathway in human malignancies. For example, nature agents such as genistein, curcumin, sulforaphane have been reported to inhibit Notch expression. We revealed that genistein inhibited cell growth, migration, invasion, EMT phenotype, formation of pancreatospheres via suppressing Notch-1 expression in PC cells [141]. Consistently, we observed that genistein inhibited Notch-1 expression through up-regulation of miR-34a in PC cells [142]. Sulforaphane, a natural compound derived from cruciferous vegetables, was shown to target the pancreatic CSCs [143-145]. Moreover, the synergistic activity of sulforaphane and sorafenib was found to eliminate CSCs from PC cells [146]. Furthermore, sulforaphane increased the sensitivity of cells to chemotherapeutic agents such as cisplatin, gemcitabine, doxorubicin and 5-flurouracil through targeting CSCs and inactivation of Notch-1 in PC. [143] More recently, Xu et al. found that Qingyihuaji formula (QYHJ), composed of traditional Chinese herbs, down regulated Notch-targeted genes Hes-1 and Hey-1 expression in both mRNA level and protein level, which was more effective than gemcitabine treatment in PC [147]. Taken together, these findings suggest that natural compounds could be non-toxic inhibitors of Notch pathway in PC cells.

Conclusions

In conclusion, Notch signaling pathway plays an important role in the development and progression of human cancers including PC. Therefore, development of inhibitors that target Notch could be a novel strategy for the treatment of PC. One alternative strategy may be to target several signaling pathways that control Notch expression (Figure 2). Since natural compounds have less toxic to human, these natural agents could be useful for prevention of tumor progression and successful treatment of PC through inactivation of Notch signaling pathway.

Figure 2.

Diagram of signaling pathways that control Notch expression in PC.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC number 81572936) and the priority academic program development of Jiangsu higher education institutions.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:115–32. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werner J, Combs SE, Springfeld C, Hartwig W, Hackert T, Buchler MW. Advanced-stage pancreatic cancer: therapy options. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:323–333. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hackert T, Buchler MW. Pancreatic cancer: advances in treatment, results and limitations. Dig Dis. 2013;31:51–56. doi: 10.1159/000347178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hidalgo M. Pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1605–1617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0901557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Recio-Boiles A, Ilmer M, Rhea PR, Kettlun C, Heinemann ML, Ruetering J, Vykoukal J, Alt E. JNK pathway inhibition selectively primes pancreatic cancer stem cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis without affecting the physiology of normal tissue resident stem cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:9890–906. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zheng L, Zhou Z, He Z. Knockdown of PFTK1 inhibits tumor cell proliferation, invasion and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:14005–14012. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y, Wang Y, Li L, Kong R, Pan S, Ji L, Liu H, Chen H, Sun B. Hyperoside induces apoptosis and inhibits growth in pancreatic cancer via Bcl-2 family and NF-kappaB signaling pathway both in vitro and in vivo. Tumour Biol. 2015;37:7345–55. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-4552-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gan H, Liu H, Zhang H, Li Y, Xu X, Xu J. SHh-Gli1 signaling pathway promotes cell survival by mediating baculoviral IAP repeat-containing 3 (BIRC3) gene in pancreatic cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:9943–50. doi: 10.1007/s13277-016-4898-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao JK, Wang LX, Long B, Ye XT, Su JN, Yin XY, Zhou XX, Wang ZW. Arsenic trioxide inhibits cell growth and invasion via down-regulation of Skp2 in pancreatic cancer cells. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:3805–3810. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.9.3805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yen WC, Fischer MM, Axelrod F, Bond C, Cain J, Cancilla B, Henner WR, Meisner R, Sato A, Shah J, Tang T, Wallace B, Wang M, Zhang C, Kapoun AM, Lewicki J, Gurney A, Hoey T. Targeting Notch signaling with a Notch2/Notch3 antagonist (tarextumab) inhibits tumor growth and decreases tumor-initiating cell frequency. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:2084–2095. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu H, Zhou L, Awadallah A, Xin W. Significance of Notch1-signaling pathway in human pancreatic development and carcinogenesis. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2013;21:242–247. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e3182655ab7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vo K, Amarasinghe B, Washington K, Gonzalez A, Berlin J, Dang TP. Targeting notch pathway enhances rapamycin antitumor activity in pancreas cancers through PTEN phosphorylation. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:138. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiorean EG, Coveler AL. Pancreatic cancer: optimizing treatment options, new, and emerging targeted therapies. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2015;9:3529–3545. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S60328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranganathan P, Weaver KL, Capobianco AJ. Notch signalling in solid tumours: a little bit of everything but not all the time. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:338–351. doi: 10.1038/nrc3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miele L. Notch signaling. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:1074–1079. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Espinoza I, Miele L. Deadly crosstalk: Notch signaling at the intersection of EMT and cancer stem cells. Cancer Lett. 2013;341:41–5. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Han F, Wu J, Lee SW, Chan CH, Wu CY, Yang WL, Gao Y, Zhang X, Jeong YS, Moten A, Samaniego F, Huang P, Liu Q, Zeng YX, Lin HK. The role of Skp2 in hematopoietic stem cell quiescence, pool size, and self-renewal. Blood. 2011;118:5429–5438. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-312785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espinoza I, Pochampally R, Xing F, Watabe K, Miele L. Notch signaling: targeting cancer stem cells and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Onco Targets and therapy. 2013;6:1249–1259. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S36162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Avila JL, Kissil JL. Notch signaling in pancreatic cancer: oncogene or tumor suppressor? Trends Mol Med. 2013;19:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicolas M, Wolfer A, Raj K, Kummer JA, Mill P, van Noort M, Hui CC, Clevers H, Dotto GP, Radtke F. Notch1 functions as a tumor suppressor in mouse skin. Nat Genet. 2003;33:416–421. doi: 10.1038/ng1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanlon L, Avila JL, Demarest RM, Troutman S, Allen M, Ratti F, Rustgi AK, Stanger BZ, Radtke F, Adsay V, Long F, Capobianco AJ, Kissil JL. Notch1 functions as a tumor suppressor in a model of K-ras-induced pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4280–4286. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomas MM, Zhang Y, Mathew E, Kane KT, Maillard I, Pasca di Magliano M. Epithelial Notch signaling is a limiting step for pancreatic carcinogenesis. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:862. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tremblay I, Pare E, Arsenault D, Douziech M, Boucher MJ. The MEK/ERK pathway promotes NOTCH signalling in pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e85502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hingorani SR, Petricoin EF, Maitra A, Rajapakse V, King C, Jacobetz MA, Ross S, Conrads TP, Veenstra TD, Hitt BA, Kawaguchi Y, Johann D, Liotta LA, Crawford HC, Putt ME, Jacks T, Wright CV, Hruban RH, Lowy AM, Tuveson DA. Preinvasive and invasive ductal pancreatic cancer and its early detection in the mouse. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:437–450. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyamoto Y, Maitra A, Ghosh B, Zechner U, Argani P, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Sriuranpong V, Iso T, Meszoely IM, Wolfe MS, Hruban RH, Ball DW, Schmid RM, Leach SD. Notch mediates TGF alpha-induced changes in epithelial differentiation during pancreatic tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:565–576. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pasca di Magliano M, Sekine S, Ermilov A, Ferris J, Dlugosz AA, Hebrok M. Hedgehog/Ras interactions regulate early stages of pancreatic cancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20:3161–3173. doi: 10.1101/gad.1470806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanger BZ, Stiles B, Lauwers GY, Bardeesy N, Mendoza M, Wang Y, Greenwood A, Cheng KH, McLaughlin M, Brown D, Depinho RA, Wu H, Melton DA, Dor Y. Pten constrains centroacinar cell expansion and malignant transformation in the pancreas. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma YC, Shi C, Zhang YN, Wang LG, Liu H, Jia HT, Zhang YX, Sarkar FH, Wang ZS. The tyrosine kinase c-Src directly mediates growth factor-induced Notch-1 and Furin interaction and Notch-1 activation in pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin NY, Distler A, Beyer C, Philipi-Schobinger A, Breda S, Dees C, Stock M, Tomcik M, Niemeier A, Dell’Accio F, Gelse K, Mattson MP, Schett G, Distler JH. Inhibition of Notch1 promotes hedgehog signalling in a HES1-dependent manner in chondrocytes and exacerbates experimental osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:2037–2044. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang S, Chung WC, Xu K. Lunatic Fringe is a potent tumor suppressor in Kras-initiated pancreatic cancer. Oncogene. 2015;35:2485–95. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weekes CD, Winn RA. The many faces of wnt and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma oncogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2011;3:3676–3686. doi: 10.3390/cancers3033676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leask A. Sonic advance: CCN1 regulates sonic hedgehog in pancreatic cancer. J Cell Commun Signal. 2013;7:61–62. doi: 10.1007/s12079-012-0187-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong X, Lin Q, Aihara A, Li Y, Huang CK, Chung W, Tang Q, Chen X, Carlson R, Nadolny C, Gabriel G, Olsen M, Wands JR. Aspartate beta-Hydroxylase expression promotes a malignant pancreatic cellular phenotype. Oncotarget. 2015;6:1231–1248. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gao J, Azmi AS, Aboukameel A, Kauffman M, Shacham S, Abou-Samra AB, Mohammad RM. Nuclear retention of Fbw7 by specific inhibitors of nuclear export leads to Notch1 degradation in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2014;5:3444–3454. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tzeng CW, Frolov A, Frolova N, Jhala NC, Howard JH, Vickers SM, Buchsbaum DJ, Heslin MJ, Arnoletti JP. EGFR genomic gain and aberrant pathway signaling in pancreatic cancer patients. J Surg Res. 2007;143:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.01.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Boonstra J, Rijken P, Humbel B, Cremers F, Verkleij A, van Bergen en Henegouwen P. The epidermal growth factor. Cell Biol Int. 1995;19:413–430. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1995.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z, Sengupta R, Banerjee S, Li Y, Zhang Y, Rahman KM, Aboukameel A, Mohammad R, Majumdar AP, Abbruzzese JL, Sarkar FH. Epidermal growth factor receptor-related protein inhibits cell growth and invasion in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7653–7660. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Auer JS, Nagel AC, Schulz A, Wahl V, Preiss A. Local overexpression of Su(H)-MAPK variants affects Notch target gene expression and adult phenotypes in Drosophila. Data Brief. 2015;5:852–863. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Y, Banerjee S, Wang ZW, Marciniak DJ, Majumdar AP, Sarkar FH. Epidermal growth factor receptor-related protein inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis of BxPC3 pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65:3877–3882. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y, Banerjee S, Wang Z, Xu H, Zhang L, Mohammad R, Aboukameel A, Adsay NV, Che M, Abbruzzese JL, Majumdar AP, Sarkar FH. Antitumor activity of epidermal growth factor receptor-related protein is mediated by inactivation of ErbB receptors and nuclear factor-kappaB in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1025–1032. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jin Y, Kim HP, Cao J, Zhang M, Ifedigbo E, Choi AM. Caveolin-1 regulates the secretion and cytoprotection of Cyr61 in hyperoxic cell death. FASEB J. 2009;23:341–350. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-108423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee SJ, Zhang M, Hu K, Lin L, Zhang D, Jin Y. CCN1 suppresses pulmonary vascular smooth muscle contraction in response to hypoxia. Pulm Circ. 2015;5:716–722. doi: 10.1086/683812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Babic AM, Kireeva ML, Kolesnikova TV, Lau LF. CYR61, a product of a growth factor-inducible immediate early gene, promotes angiogenesis and tumor growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6355–6360. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Perbal B. CCN proteins: multifunctional signalling regulators. Lancet. 2004;363:62–64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lau LF. CCN1/CYR61: the very model of a modern matricellular protein. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:3149–3163. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0778-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haque I, Mehta S, Majumder M, Dhar K, De A, McGregor D, Van Veldhuizen PJ, Banerjee SK, Banerjee S. Cyr61/CCN1 signaling is critical for epithelial-mesenchymal transition and stemness and promotes pancreatic carcinogenesis. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:8. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haque I, De A, Majumder M, Mehta S, McGregor D, Banerjee SK, Van Veldhuizen P, Banerjee S. The matricellular protein CCN1/Cyr61 is a critical regulator of Sonic Hedgehog in pancreatic carcinogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:38569–38579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.389064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fox JL, Ismail F, Azad A, Ternette N, Leverrier S, Edelmann MJ, Kessler BM, Leigh IM, Jackson S, Storey A. Tyrosine dephosphorylation is required for Bak activation in apoptosis. EMBO J. 2010;29:3853–3868. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marampon F, Bossi G, Ciccarelli C, Di Rocco A, Sacchi A, Pestell RG, Zani BM. MEK/ERK inhibitor U0126 affects in vitro and in vivo growth of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:543–551. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ciccarelli C, Vulcano F, Milazzo L, Gravina GL, Marampon F, Macioce G, Giampaolo A, Tombolini V, Di Paolo V, Hassan HJ, Zani BM. Key role of MEK/ERK pathway in sustaining tumorigenicity and in vitro radioresistance of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma stem-like cell population. Mol Cancer. 2016;15:16. doi: 10.1186/s12943-016-0501-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.An XZ, Zhao ZG, Luo YX, Zhang R, Tang XQ, Hao DL, Zhao X, Lv X, Liu DP. Netrin-1 suppresses the MEK/ERK pathway and ITGB4 in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:24719–33. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jia S, VanDusen WJ, Diehl RE, Kohl NE, Dixon RA, Elliston KO, Stern AM, Friedman PA. cDNA cloning and expression of bovine aspartyl (asparaginyl) beta-hydroxylase. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14322–14327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Engel J. EGF-like domains in extracellular matrix proteins: localized signals for growth and differentiation? FEBS Lett. 1989;251:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81417-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patel N, Khan AO, Mansour A, Mohamed JY, Al-Assiri A, Haddad R, Jia X, Xiong Y, Megarbane A, Traboulsi EI, Alkuraya FS. Mutations in ASPH cause facial dysmorphism, lens dislocation, anterior-segment abnormalities, and spontaneous filtering blebs, or Traboulsi syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;94:755–759. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Luu M, Sabo E, de la Monte SM, Greaves W, Wang J, Tavares R, Simao L, Wands JR, Resnick MB, Wang L. Prognostic value of aspartyl (asparaginyl)-beta-hydroxylase/humbug expression in non-small cell lung carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2009;40:639–644. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ince N, de la Monte SM, Wands JR. Overexpression of human aspartyl (asparaginyl) beta-hydroxylase is associated with malignant transformation. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1261–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aihara A, Huang CK, Olsen MJ, Lin Q, Chung W, Tang Q, Dong X, Wands JR. A cell-surface beta-hydroxylase is a biomarker and therapeutic target for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2014;60:1302–1313. doi: 10.1002/hep.27275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maeda T, Sepe P, Lahousse S, Tamaki S, Enjoji M, Wands JR, de la Monte SM. Antisense oligodeoxynucleotides directed against aspartyl (asparaginyl) beta-hydroxylase suppress migration of cholangiocarcinoma cells. J Hepatol. 2003;38:615–622. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00052-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang CK, Iwagami Y, Aihara A, Chung W, de la Monte S, Thomas JM, Olsen M, Carlson R, Yu T, Dong X, Wands J. Anti-Tumor effects of second generation beta-hydroxylase inhibitors on cholangiocarcinoma development and progression. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150336. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Weng AP, Nam Y, Wolfe MS, Pear WS, Griffin JD, Blacklow SC, Aster JC. Growth suppression of pre-T acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells by inhibition of notch signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:655–664. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.2.655-664.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tu L, Fang TC, Artis D, Shestova O, Pross SE, Maillard I, Pear WS. Notch signaling is an important regulator of type 2 immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1037–1042. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Naganuma S, Whelan KA, Natsuizaka M, Kagawa S, Kinugasa H, Chang S, Subramanian H, Rhoades B, Ohashi S, Itoh H, Herlyn M, Diehl JA, Gimotty PA, Klein-Szanto AJ, Nakagawa H. Notch receptor inhibition reveals the importance of cyclin D1 and Wnt signaling in invasive esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2012;2:459–475. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crusio KM, King B, Reavie LB, Aifantis I. The ubiquitous nature of cancer: the role of the SCF(Fbw7) complex in development and transformation. Oncogene. 2010;29:4865–4873. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cao J, Ge MH, Ling ZQ. Fbxw7 tumor suppressor: a Vital regulator contributes to human tumorigenesis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2496. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Welcker M, Clurman BE. FBW7 ubiquitin ligase: a tumour suppressor at the crossroads of cell division, growth and differentiation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:83–93. doi: 10.1038/nrc2290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Minella AC, Clurman BE. Mechanisms of tumor suppression by the SCF(Fbw7) Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1356–1359. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.10.2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lau AW, Fukushima H, Wei W. The Fbw7 and betaTRCP E3 ubiquitin ligases and their roles in tumorigenesis. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:2197–2212. doi: 10.2741/4045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Z, Inuzuka H, Zhong J, Wan L, Fukushima H, Sarkar FH, Wei W. Tumor suppressor functions of FBW7 in cancer development and progression. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1409–1418. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Oberg C, Li J, Pauley A, Wolf E, Gurney M, Lendahl U. The Notch intracellular domain is ubiquitinated and negatively regulated by the mammalian Sel-10 homolog. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:35847–35853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103992200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mo JS, Ann EJ, Yoon JH, Jung J, Choi YH, Kim HY, Ahn JS, Kim SM, Kim MY, Hong JA, Seo MS, Lang F, Choi EJ, Park HS. Serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 (SGK1) controls Notch1 signaling by downregulation of protein stability through Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:100–112. doi: 10.1242/jcs.073924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ma J, Fang B, Zeng F, Ma C, Pang H, Cheng L, Shi Y, Wang H, Yin B, Xia J, Wang Z. Down-regulation of miR-223 reverses epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:1740–1749. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dummler B, Hemmings BA. Physiological roles of PKB/Akt isoforms in development and disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:231–235. doi: 10.1042/BST0350231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chin YR, Toker A. Function of Akt/PKB signaling to cell motility, invasion and the tumor stroma in cancer. Cell Signal. 2009;21:470–476. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jiang BH, Liu LZ. AKT signaling in regulating angiogenesis. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2008;8:19–26. doi: 10.2174/156800908783497122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yang Y, Mo X. An analysis of the effects and the molecular mechanism of deep hypothermic low flow on brain tissue in Mice. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;22:76–83. doi: 10.5761/atcs.oa.15-00333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Song G, Ouyang G, Bao S. The activation of Akt/PKB signaling pathway and cell survival. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:59–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00337.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hers I, Vincent EE, Tavare JM. Akt signalling in health and disease. Cell Signal. 2011;23:1515–1527. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhang G, Wang C, Sun M, Li J, Wang B, Jin C, Hua P, Song G, Zhang Y, Nguyen LL, Cui R, Liu R, Wang L, Zhang X. Cinobufagin inhibits tumor growth by inducing intrinsic apoptosis through AKT signaling pathway in human nonsmall cell lung cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:28935–46. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li L, Zhang J, Xiong N, Li S, Chen Y, Yang H, Wu C, Zeng H, Liu Y. Notch-1 signaling activates NF-kappaB in human breast carcinoma MDA-MB-231 cells via PP2A-dependent AKT pathway. Med Oncol. 2016;33:33. doi: 10.1007/s12032-016-0747-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li Z, Dong X, Wang Z, Liu W, Deng N, Ding Y, Tang L, Hla T, Zeng R, Li L, Wu D. Regulation of PTEN by Rho small GTPases. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:399–404. doi: 10.1038/ncb1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fu Y, Rubin CS. Protein kinase D: coupling extracellular stimuli to the regulation of cell physiology. EMBO Rep. 2011;12:785–796. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Johannes FJ, Prestle J, Eis S, Oberhagemann P, Pfizenmaier K. PKCu is a novel, atypical member of the protein kinase C family. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6140–6148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Durand N, Borges S, Storz P. Protein Kinase D Enzymes as Regulators of EMT and Cancer Cell Invasion. J Clin Med. 2016;5 doi: 10.3390/jcm5020020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ferdaoussi M, Bergeron V, Zarrouki B, Kolic J, Cantley J, Fielitz J, Olson EN, Prentki M, Biden T, MacDonald PE, Poitout V. G protein-coupled receptor (GPR)40-dependent potentiation of insulin secretion in mouse islets is mediated by protein kinase D1. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2682–2692. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2650-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Harikumar KB, Kunnumakkara AB, Ochi N, Tong Z, Deorukhkar A, Sung B, Kelland L, Jamieson S, Sutherland R, Raynham T, Charles M, Bagherzadeh A, Foxton C, Boakes A, Farooq M, Maru D, Diagaradjane P, Matsuo Y, Sinnett-Smith J, Gelovani J, Krishnan S, Aggarwal BB, Rozengurt E, Ireson CR, Guha S. A novel small-molecule inhibitor of protein kinase D blocks pancreatic cancer growth in vitro and in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9:1136–1146. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Guha S, Tanasanvimon S, Sinnett-Smith J, Rozengurt E. Role of protein kinase D signaling in pancreatic cancer. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1946–1954. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liou GY, Doppler H, Braun UB, Panayiotou R, Scotti Buzhardt M, Radisky DC, Crawford HC, Fields AP, Murray NR, Wang QJ, Leitges M, Storz P. Protein kinase D1 drives pancreatic acinar cell reprogramming and progression to intraepithelial neoplasia. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6200. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang Z, Azmi AS, Ahmad A, Banerjee S, Wang S, Sarkar FH, Mohammad RM. TW-37, a small-molecule inhibitor of Bcl-2, inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in pancreatic cancer: involvement of Notch-1 signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2757–2765. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Maniati E, Bossard M, Cook N, Candido JB, Emami-Shahri N, Nedospasov SA, Balkwill FR, Tuveson DA, Hagemann T. Crosstalk between the canonical NF-kappaB and Notch signaling pathways inhibits Ppargamma expression and promotes pancreatic cancer progression in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4685–4699. doi: 10.1172/JCI45797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mortenson MM, Galante JG, Gilad O, Schlieman MG, Virudachalam S, Kung HJ, Bold RJ. BCL-2 functions as an activator of the AKT signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:1171–1179. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mohammad RM, Wang S, Banerjee S, Wu X, Chen J, Sarkar FH. Nonpeptidic small-molecule inhibitor of Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL, (-)-Gossypol, enhances biological effect of genistein against BxPC-3 human pancreatic cancer cell line. Pancreas. 2005;31:317–324. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000179731.46210.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Merino D, Bouillet P. The Bcl-2 family in autoimmune and degenerative disorders. Apoptosis. 2009;14:570–583. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0308-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Youle RJ, Strasser A. The BCL-2 protein family: opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:47–59. doi: 10.1038/nrm2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Scorrano L, Korsmeyer SJ. Mechanisms of cytochrome c release by proapoptotic BCL-2 family members. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;304:437–444. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00615-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Domingo-Domenech J, Vidal SJ, Rodriguez-Bravo V, Castillo-Martin M, Quinn SA, Rodriguez-Barrueco R, Bonal DM, Charytonowicz E, Gladoun N, de la Iglesia-Vicente J, Petrylak DP, Benson MC, Silva JM, Cordon-Cardo C. Suppression of acquired docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer through depletion of notch- and hedgehog-dependent tumor-initiating cells. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:373–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Perumalsamy LR, Nagala M, Sarin A. Notch-activated signaling cascade interacts with mitochondrial remodeling proteins to regulate cell survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:6882–6887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Campbell KJ, Perkins ND. Regulation of NF-kappaB function. Biochem Soc Symp. 2006:165–180. doi: 10.1042/bss0730165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Perkins ND. Integrating cell-signalling pathways with NF-kappaB and IKK function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Grilli M, Chiu JJ, Lenardo MJ. NF-kappa B and Rel: participants in a multiform transcriptional regulatory system. Int Rev Cytol. 1993;143:1–62. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61873-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Lu Z, Li Y, Takwi A, Li B, Zhang J, Conklin DJ, Young KH, Martin R. miR-301a as an NF-kappaB activator in pancreatic cancer cells. EMBO J. 2011;30:57–67. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wu WK, Cho CH, Lee CW, Fan D, Wu K, Yu J, Sung JJ. Dysregulation of cellular signaling in gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2010;295:144–153. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Osipo C, Golde TE, Osborne BA, Miele LA. Off the beaten pathway: the complex cross talk between Notch and NF-kappaB. Lab Invest. 2008;88:11–17. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lutz MP, Esser IB, Flossmann-Kast BB, Vogelmann R, Luhrs H, Friess H, Buchler MW, Adler G. Overexpression and activation of the tyrosine kinase Src in human pancreatic carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;243:503–508. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hsieh HL, Sun CC, Wang TS, Yang CM. PKC-delta/c-Src-mediated EGF receptor transactivation regulates thrombin-induced COX-2 expression and PGE(2) production in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1783:1563–1575. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lee CW, Lin CC, Lin WN, Liang KC, Luo SF, Wu CB, Wang SW, Yang CM. TNF-alpha induces MMP-9 expression via activation of Src/EGFR, PDGFR/PI3K/Akt cascade and promotion of NF-kappaB/p300 binding in human tracheal smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L799–812. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00311.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ishizawar R, Parsons SJ. c-Src and cooperating partners in human cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:209–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sade H, Krishna S, Sarin A. The anti-apoptotic effect of Notch-1 requires p56lck-dependent, Akt/PKB-mediated signaling in T cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:2937–2944. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ho DM, Pallavi SK, Artavanis-Tsakonas S. The Notch-mediated hyperplasia circuitry in Drosophila reveals a Src-JNK signaling axis. Elife. 2015;4:e05996. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Rohatgi R, Milenkovic L, Scott MP. Patched1 regulates hedgehog signaling at the primary cilium. Science. 2007;317:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1139740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Pereira J, Johnson WE, O’Brien SJ, Jarvis ED, Zhang G, Gilbert MT, Vasconcelos V, Antunes A. Evolutionary genomics and adaptive evolution of the Hedgehog gene family (Shh, Ihh and Dhh) in vertebrates. PLoS One. 2014;9:e74132. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Barakat MT, Humke EW, Scott MP. Learning from Jekyll to control Hyde: hedgehog signaling in development and cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:337–348. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Inaguma S, Riku M, Ito H, Tsunoda T, Ikeda H, Kasai K. GLI1 orchestrates CXCR4/CXCR7 signaling to enhance migration and metastasis of breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:33648–33657. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Xin Y, Shen XD, Cheng L, Hong DF, Chen B. Perifosine inhibits S6K1-Gli1 signaling and enhances gemcitabine-induced anti-pancreatic cancer efficiency. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73:711–719. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Subramani R, Gonzalez E, Nandy SB, Arumugam A, Camacho F, Medel J, Alabi D, Lakshmanaswamy R. Gedunin inhibits pancreatic cancer by altering sonic hedgehog signaling pathway. Oncotarget. 2016 doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8055. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Ding D, Lim KS, Eberhart CG. Arsenic trioxide inhibits Hedgehog, Notch and stem cell properties in glioblastoma neurospheres. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2014;2:31. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-2-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Schreck KC, Taylor P, Marchionni L, Gopalakrishnan V, Bar EE, Gaiano N, Eberhart CG. The Notch target Hes1 directly modulates Gli1 expression and Hedgehog signaling: a potential mechanism of therapeutic resistance. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:6060–6070. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wall DS, Mears AJ, McNeill B, Mazerolle C, Thurig S, Wang Y, Kageyama R, Wallace VA. Progenitor cell proliferation in the retina is dependent on Notch-independent sonic hedgehog/Hes1 activity. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:101–112. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200805155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Ingram WJ, McCue KI, Tran TH, Hallahan AR, Wainwright BJ. Sonic Hedgehog regulates Hes1 through a novel mechanism that is independent of canonical Notch pathway signalling. Oncogene. 2008;27:1489–1500. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ristorcelli E, Lombardo D. Targeting Notch signaling in pancreatic cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:541–552. doi: 10.1517/14728221003769895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Clevers H. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell. 2006;127:469–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Clevers H, Nusse R. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling and disease. Cell. 2012;149:1192–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Takahashi-Yanaga F, Kahn M. Targeting Wnt signaling: can we safely eradicate cancer stem cells? Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3153–3162. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.So JY, Suh N. Targeting cancer stem cells in solid tumors by vitamin D. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2015;148:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.White BD, Chien AJ, Dawson DW. Dysregulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in gastrointestinal cancers. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:219–232. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Morris JP 4th, Wang SC, Hebrok M. KRAS, Hedgehog, Wnt and the twisted developmental biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:683–695. doi: 10.1038/nrc2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Pires-daSilva A, Sommer RJ. The evolution of signalling pathways in animal development. Nat Rev Genet. 2003;4:39–49. doi: 10.1038/nrg977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Nusse R, Fuerer C, Ching W, Harnish K, Logan C, Zeng A, ten Berge D, Kalani Y. Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:59–66. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Zeng YA, Nusse R. Wnt proteins are self-renewal factors for mammary stem cells and promote their long-term expansion in culture. Cell Stem Cell. 2010;6:568–577. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Tian H, Biehs B, Chiu C, Siebel CW, Wu Y, Costa M, de Sauvage FJ, Klein OD. Opposing activities of Notch and Wnt signaling regulate intestinal stem cells and gut homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2015;11:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Li XY, Zhai WJ, Teng CB. Notch Signaling in Pancreatic Development. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17010048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Foltz DR, Santiago MC, Berechid BE, Nye JS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3beta modulates notch signaling and stability. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1006–1011. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00888-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Gu B, Watanabe K, Sun P, Fallahi M, Dai X. Chromatin effector Pygo2 mediates Wnt-notch crosstalk to suppress luminal/alveolar potential of mammary stem and basal cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:48–61. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kwon C, Cheng P, King IN, Andersen P, Shenje L, Nigam V, Srivastava D. Notch post-translationally regulates beta-catenin protein in stem and progenitor cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:1244–1251. doi: 10.1038/ncb2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Miele L, Miao H, Nickoloff BJ. NOTCH signaling as a novel cancer therapeutic target. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2006;6:313–323. doi: 10.2174/156800906777441771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Espinoza I, Miele L. Notch inhibitors for cancer treatment. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;139:95–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Palagani V, El Khatib M, Kossatz U, Bozko P, Muller MR, Manns MP, Krech T, Malek NP, Plentz RR. Epithelial mesenchymal transition and pancreatic tumor initiating CD44+/EpCAM+ cells are inhibited by gamma-secretase inhibitor IX. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46514. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ponnurangam S, Dandawate PR, Dhar A, Tawfik OW, Parab RR, Mishra PD, Ranadive P, Sharma R, Mahajan G, Umar S, Weir SJ, Sugumar A, Jensen RA, Padhye SB, Balakrishnan A, Anant S, Subramaniam D. Quinomyccin A targets Notch signaling pathway in pancreatic cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:3217–3232. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Bao B, Wang Z, Ali S, Kong D, Li Y, Ahmad A, Banerjee S, Azmi AS, Miele L, Sarkar FH. Notch-1 induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition consistent with cancer stem cell phenotype in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2011;307:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 142.Xia J, Duan Q, Ahmad A, Bao B, Banerjee S, Shi Y, Ma J, Geng J, Chen Z, Rahman KM, Miele L, Sarkar FH, Wang Z. Genistein inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis through up-regulation of miR-34a in pancreatic cancer cells. Curr Drug Targets. 2012;13:1750–1756. doi: 10.2174/138945012804545597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Kallifatidis G, Labsch S, Rausch V, Mattern J, Gladkich J, Moldenhauer G, Buchler MW, Salnikov AV, Herr I. Sulforaphane increases drug-mediated cytotoxicity toward cancer stem-like cells of pancreas and prostate. Mol Ther. 2011;19:188–195. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Li SH, Fu J, Watkins DN, Srivastava RK, Shankar S. Sulforaphane regulates self-renewal of pancreatic cancer stem cells through the modulation of Sonic hedgehog-GLI pathway. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;373:217–227. doi: 10.1007/s11010-012-1493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Srivastava RK, Tang SN, Zhu W, Meeker D, Shankar S. Sulforaphane synergizes with quercetin to inhibit self-renewal capacity of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Front Biosci. 2011;3:515–528. doi: 10.2741/e266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Rausch V, Liu L, Kallifatidis G, Baumann B, Mattern J, Gladkich J, Wirth T, Schemmer P, Buchler MW, Zoller M, Salnikov AV, Herr I. Synergistic activity of sorafenib and sulforaphane abolishes pancreatic cancer stem cell characteristics. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5004–5013. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Xu Y, Xu S, Cai Y, Liu L. Qingyihuaji Formula Inhibits Pancreatic Cancer and Prolongs Survival by Downregulating Hes-1 and Hey-1. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015:145016. doi: 10.1155/2015/145016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]