Abstract

Pentachlorophenol (PCP) and Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) are environmental contaminants found in human blood. Previous studies have shown that PCP and DDT inhibit the lytic function of highly purified human natural killer (NK) lymphocytes and decrease the expression of several surface proteins on NK cells. Interleukin-1 βeta (IL-1β) is a cytokine produced by lymphocytes and monocytes and anything that elevates its levels inappropriately can lead to chronic inflammation, which among other consequences can increase tumor development and invasiveness. Here PCP and DDT were examined for their ability to alter secretion of IL-1β from immune cell preparations of various complexity: NK cells; monocyte depleted (MD) peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCS), and PBMCs. Cells were exposed to concentrations of PCP ranging from 5 µM to 0.05 µM and DDT concentrations of 2.5µM to 0.025µM for 24 h, 48 h and 6 days. Results showed that both PCP and DDT increased IL-1β secretion from all of the immune cell preparations. The specific concentrations of PCP and DDT that increased IL-1β secretion varied by donor. Immune cells from all donors showed compound-induced increases in IL-1β secretion at one or more concentration at one or more length of exposure. The mechanism of PCP stimulation of IL1-β secretion was also addressed and it appears that the MAPKs, ERK1/2 and p38, may be utilized by PCP to stimulate secretion of IL-1β.

Keywords: NK cells, MD-PBMCs, PBMCs, Pentachlorophenol, Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, Interleukin 1β

INTRODUCTION

IL-1β is one of the most powerful pro-inflammatory cytokines; it affects virtually every organ, and several human pathologies are primarily driven by unrestrained IL-1β production. Over production contributes to pathophysiological changes seen in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, neuropathic pain, inflammatory bowel disease, osteoarthritis, vascular disease, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and cancer (Dinarello, 1996; Braddock & Quinn, 2004; Dinarello, 2004; Coussens & Werb, 2002). IL-1β exerts its protective action against infections by activating several responses including the rapid recruitment of neutrophils to inflammatory sites, activation of the endothelial adhesion molecules, induction of cytokines and chemokines, and the stimulation of adaptive immunity. (Sahoo et al., 2011). IL-1β is produced by several different categories of immune cells including monocytes (Shi & Pamer, 2011), T cells (Numerof et al., 1990) and natural killer (NK) cells (De Sanctis et al., 1997). IL-1β is secreted in response to immune cell recognition of pathogen associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) through pattern recognition receptors (PRR) (Gaestel et al. 2009). Pro IL-1β matures to IL-1β by interacting with the protease, caspase 1 (Lopez-Castejon & Brough, 2011; Swaan et al., 2001; Dinarello, 1996). Caspase 1 is activated by an intracellular multiprotein complex referred to as the inflammasome. It cleaves the 31 kD pro IL-1β to the mature 17 kD form leading to its secretion (Church et al., 2008; Franchi et al., 2009; Lopez-Castejon & Brough, 2011; Martinon & Tschopp, 2007). A favorable environment for angiogenesis and metastasis results when chronic inflammation provides an abundant source of growth factors, cytokines, chemokines, prostaglandins, and reactive oxygen species (Balkwill & Mantovani 2001; Coussens & Werb, 2002). Inflammation and dysregulation in immune cells could be caused by exposure to environmental contaminants that are found in human blood.

Pentachlorophenol (PCP) is an organochlorine compound that contaminates the environment due to its various uses (ATSDR, 2001; Cirelli, 1978; Brown et al., 2005). PCP has been used as a fungicide, insecticide, herbicide, in antifouling paint, and as a wood preservative (Cirelli, 1978). It has been found in human blood with serum levels ranging from 0.26 −5 µM in individuals who live in PCP-treated log homes (Cline et al., 1989). Levels averaging 0.15 µM were found in the serum of individuals with no known exposure (Cline et al., 1989; Uhl et al., 1986). PCP exposure is associated with cancers of the blood (lymphoma and myeloma) and kidney (Demers et al., 2006; Cooper & Jones, 2008). Cytotoxic and gene expression effects of PCP in human liver and bladder cells were investigated by Wang et al. (2000). Liver cells were more resistant to the toxicity of PCP than were bladder cells and expression of cellular apoptosis susceptibility protein (CAS) decreased in cells after treatment with PCP.

4, 4′-Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) was extensively used as an agricultural pesticide throughout the world (CDC 2003; 2005; Geisz et al., 2008; Turusov et al., 2002; Loganathan, 2012). While it has been banned in many countries including the USA, it is still used in other countries primarily to control mosquitos (CDC 2003;2005). Despite its ban, DDT has been found in human bodily fluid and has been detected in measurable concentrations in blood samples within the US population (Thornton et al., 2002; Patterson et al., 2009). In countries such as Mexico where DDT is still used, it has been found in serum with concentrations as high as 23,169 ng/g of lipid (approximately 260 nM) (Koepke et al., 2004; Trejo-Acevedo et al., 2009). An association between blood levels of DDT and decreased numbers of NK cells as well as decreased NK function has been reported (Svensson et al., 1994; Eskenazi et al., 2009).

Results of prior ex vivo studies indicate that exposure of human NK cells to both PCP and DDT causes inhibition of their ability to bind and lyse tumor target cells (Reed et al., 2004; Nnodu and Whalen, 2008; Udoji et al., 2010; Hurd et al., 2012; Hurd-Brown et al., 2013). Both compounds also decrease the expression of certain cell-surface proteins needed for NK lymphocytes to bind to tumor targets (Hurd et al., 2012; Hurd-Brown et al., 2013). Dysregulation in secretion of NK-stimulatory ILs (IL-2, IL-12 and/or IL-10) and NK-inhibitory cytokine, IL-4 has been reported after exposure to PCP and DDT (Beach & Whalen, 2006). Based on the results from previous studies on the effects of PCP and DDT on immune function and the importance of IL-1β as a master regulator of immune response and inflammation, we hypothesize that PCP and DDT may alter the secretion of IL-1β from human immune cells.

In this study, preparations of immune cells with increasing complexity were utilized to investigate the effects of ex vivo exposures to PCP and DDT on the secretion of IL-1β. Human NK cells, human monocyte-depleted (MD) peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (MD-PBMCs), and PBMCs were each exposed to the compounds and secreted IL-1β levels were assessed. Monitoring exposure to PCP and DDT on these increasingly reconstituted preparations of immune cells allows us to see whether the effects of the compounds are dependent on the nature of the cell preparation. An additional goal of this study was to investigate the mechanism of any compound-induced increases in IL-1β secretion. Thus, additional studies were done where PBMCs were pre-treated with Caspase-1 inhibitor, p44/42 (ERK 1/2) pathway inhibitor, JNK pathway inhibitor, p38 inhibitor, or NFĸB inhibitor before exposure to the compounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of PBMCs, and Monocyte Depletion- PBMCs

PBMCs were isolated from leukocyte filters (PALL-RCPL or FLEX) obtained from the Red Cross Blood Bank (Nashville, TN) as described in (Meyer et al., 2005). Leukocytes were obtained from the filters by back-flushing the filters with an elution medium which contains (sterile phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 mM disodium EDTA and 2.5% [w/v] sucrose) and then collecting the eluent. The eluent was layered onto LymphoSep cell separation medium (1.077g/mL) (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA) and centrifuged at 1200g for 30–50 min. Following centrifuging and washing, the cells were layered on bovine calf serum for platelet removal. The cells were then suspended in RPMI-1640 complete medium which consisted of RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated BCS, 2 mM L-glutamine and 50 U penicillin G with 50 µg streptomycin/mL Monocyte-depleted (MD) PBMCs (10–20% CD16+, 10–20 % CD56+, 70–80% CD3+, 3–5% CD19+, 2–20% CD14+) were prepared by incubating PBMCs in glass Petri dishes (150 × 15 mm) at 37 °C and air/CO2, 19:1 for 1 h.

Preparation of NK cells

NK cells were isolated from buffy coats (source leukocytes from healthy adult donors) purchased from Key Biologics, LLC (Memphis, TN) using a rosetting procedure. RosetteSep human NK cell enrichment antibody cocktail (0.6–0.8 mL) (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada) was added to 45 mL of the buffy coat. The mixture was incubated for 20 min at room temperature (~ 25° C). Eight mL of the mixture was layered onto 4 mL of LymphoSep (1.077 g/mL) and centrifuged at 1200 g for 30–50 min. The NK cells were collected and washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4 and stored in complete media (RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated bovine calf serum (BCS), 2 mM L-glutamine and 50 U penicillin G with 50 µg streptomycin/ml) at 1 million cells/mL at 37 °C and air/CO2, 19:1.

Chemical Preparation

DDT and PCP were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Stock solutions were prepared as 100 mM solutions in Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). Desired concentrations of either DDT or PCP were prepared by dilution of the desired stock into cell culture media.

Inhibitor Preparation

Enzyme inhibitors were purchased from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA).The stock solution for each inhibitor was a 50 mM solution in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). Capase-1 inhibitor II, MEK 1/2 pathway inhibitor (PD98059), p38 inhibitor (SB202190), JNK inhibitor (B178D3), and NFκB inhibitor (BAY11–7085) were prepared by dilution of the stock solution into cell culture media.

Cell Treatments

PBMCs, MD-PBMCs, and NK cells (at a concentration of 1.5 million cells/ mL) were treated with PCP (0.05–5 µM) and appropriate control for 24 h, 48 h, and 6 days. Additionally, each of the above types of cell preparations were treated with DDT (0.025–2.5 µM) and appropriate control for 24h, 48h, and 6 days. Once the incubation period was complete, the cells were pelleted and supernatants were obtained and stored at −70 C until assaying for IL-1β. For the pathway inhibitor experiments, PBMCs were treated with enzyme inhibitors 1 h prior to adding PCP at concentrations of 5, 2.5, and 1 µM for 24 h. After the cells were incubated, the cells were pelleted and supernatants were obtained and stored at −70 C until assaying for IL-1β.

Cell Viability

Cell viability was measured at the end of the 24 h, 48 h and 6 day exposure period. Viability was determined using the trypan blue exclusion method. Cells were mixed with trypan blue and counted using a hemocytometer. The total number of cells and the number of dead were counted for both control and treated cells to determine the percent viable cells.

IL-1β Secretion Assay

IL-1β levels were measured using the BD OptEIA™ Human IL-1β enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (BD-Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). A 96-well micro well plate, designed for ELISA assays (Fisher, Pittsburgh, PA), was coated with a capture antibody for IL-1β that was diluted in coating buffer. The ELISA plate was incubated with the capture antibody overnight at 4 °C. After the incubation, the capture antibody was removed and blocking solution (PBS and bovine calf serum) was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 1h. Following the blocking step, cell supernatants and IL-1β standards were added to the and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Detection antibody linked to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) was then added followed by substrate. The reaction was stopped by addition of 1 M phosphoric acid and absorbance was measured at 450 nm on a Thermo Labsystems Multiskan MCC/340 plate reader (Fisher Scientific).

Statistical Analysis

Data was analyzed using ANOVA and the Student’s t test. Data were initially compared within a given experimental setup by ANOVA. A significant ANOVA was followed by pair wise analysis of control versus exposed data using Student’s t test, a p value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Viability of NK cells, MD-PBMCs, and PBMCs exposed to PCP

Exposures to PCP (0.05–5 µM) for 24 h and 48 h had no effect on the viability of NK cells, MD-PBMCs, and PBMCs. Exposures of NK cells and PBMCs to these same concentrations of PCP for 6 d also caused no decreases in viability when compared to control cells (data not shown). However MD-PBMCs showed a small but significant decrease in viability with exposures to 1µM (13% decrease) and 5µM PCP (7% decrease) after 6 days.

Viability of NK cells, MD-PBMCs, and PBMCs exposed to DDT

Exposure of NK cells, MD-PBMCs, and PBMCs to 0.025–2.5 µM DDT for 24 h, 48 h, or 6 d produced no significant decreases in cell viability as compared to the control (data not shown).

Viability of PBMCs treated with selective enzyme inhibitors and then exposed to PCP

PBMCs pre-treated for 1 h with selected signaling pathway inhibitors followed by exposure to 1, 2.5, or 5 µM PCP for 24 h were also examined for viability. There were no significant changes in the viability of these cells compared to appropriate controls with any of the inhibitors (data not shown).

Effects of PCP Exposures on Secretion of IL-1β by NK cells

Table 1 shows the effects on IL-1β secretion by NK cells exposed to 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2.5, and 5 µM PCP for 24 h, 48 h, and 6 days. Cells from 4 donors were tested. IL-1β secretion from NK cells of donor KB188 (KB=Key Biologic buffy coat) was increased by 1.3 fold when the cells were exposed to 2.5 µM PCP for 24 h (p<0.05). IL-1β secretion was not significantly increased at this same concentration in cells from the other 3 donors and was significantly decreased at the 5 µM exposure after 24 h. 48 h exposures to one or more concentration of PCP caused increases in IL-1β secretion in cells from 3 of the 4 donors (KB188, 192, 194). NK cells from donor KB196 showed increased secretion of IL-β with 0.05 and 0.1 µM exposures to PCP after 6 days. Thus, all donor NK cells showed increased secretion of IL-1β after exposure to PCP, however, the concentrations and lengths of exposure at which these increases occurred varied among the donors.

Table 1.

Effects of 24 h, 48 h, 6 day exposures to PCP on IL1β secretion from NK cells.

| 24 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in pg/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[PCP] µM |

KB188 | KB192 | KB194 | KB196 |

| 0 | 73345±6628 | 108±5 | 207±30 | 132±44 |

| 0.05 | 56693±8398 | 93±5* | 203±33 | 202±32 |

| 0.1 | 84823±7309 | 109±7 | 167±25 | 215±40 |

| 0.25 | 86243±5274 | 72±6 * | 149±16 | 145±9 |

| 0.5 | 64243±4225 | 99±10 | 191±18 | 170±16 |

| 1 | 86475±1945 | 50±10* | 153±21 | 132±15 |

| 2.5 | 97751±2472* | 25±1* | 81±25* | 50±16 |

| 5 | 81954±1158 | 42±2* | 0±5* | 0±6* |

| 48 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[PCP] µM |

KB188 | KB192 | KB194 | KB196 |

| 0 | 66929±3421 | 154±4 | 237±16 | 229±35 |

| 0.05 | 76262±3303* | 160±17 | 254±21 | 278±60 |

| 0.1 | 73359±1549 | 168±5* | 248±26 | 290±17 |

| 0.25 | 80972±389* | 207±8* | 227±7 | 312±43 |

| 0.5 | 83574±2710* | 243±18* | 308±12* | 219±22 |

| 1 | 84026±1231* | 202±15* | 273±11* | 233±20 |

| 2.5 | 83703±5892* | 67±2* | 169±38 | 41±15* |

| 5 | 74004±2972* | 50±1 * | 7±4* | 0±2* |

| 6day | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [PCP] µM |

KB188 | KB192 | KB194 | KB196 |

| 0 | 5087±248 | 176±9 | 116±3 | 134±122 |

| 0.05 | 6837±282* | 110±5* | 200±22* | 207±210* |

| 0.1 | 4636±379 | 148±6* | 187±5* | 229±237* |

| 0.25 | 5447±86 | 178±2 | 183±6* | 157±154 |

| 0.5 | 5252±328 | 221±18* | 160±3* | 188±194 |

| 1 | 5594±253 | 210±5* | 165±8* | 164±160 |

| 2.5 | 6054±300* | 82±5* | 80±8* | 58±49* |

| 5 | 5137±142 | 76±2* | 0±5* | 0±0 |

Values are mean±S.D. of triplicate determinations.

Indicates a significant change in secretion compared to control cells (cells treated with vehicle alone), p<0.05

Effects of PCP Exposures on Secretion of IL-1β by MD-PBMCs

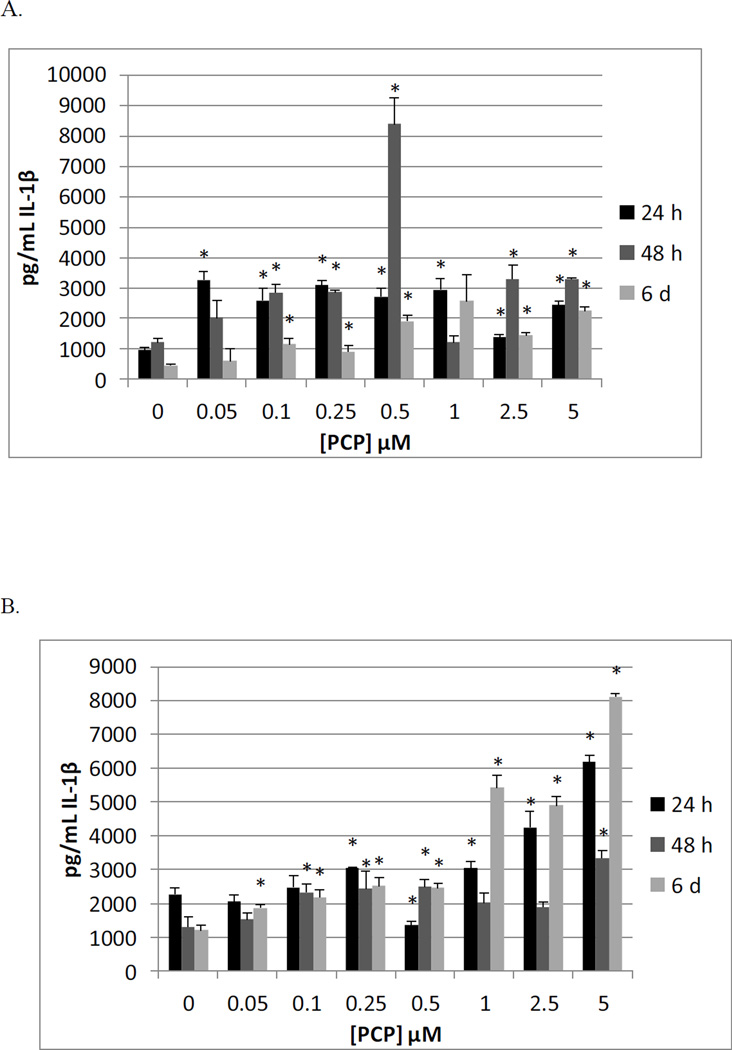

The effects of exposures to PCP on secretion of IL-1β from MD-PBMCs after 24 h, 48 h, and 6 d from 4 donors (F=filter obtained from the Red Cross) are shown in Table 2. This preparation consists mainly of NK cells and T cells. When MD-PBMCs were exposed to PCP for 24 h, there were statistically significant increases in IL-1β secretion at the 5 µM concentration of PCP for all donors. The fold increases were 1.7 fold for F209, 1.8 fold for F239, 2.5 fold for F241, and 2 fold for F243 when compared to the control. All but one of the donors showed increased secretion at other concentrations as well, but the concentration at which these increases occurred varied among the donors. The results after 48 h and 6 d of exposure to PCP were similar to those seen after 24 h. Results from a representative experiment are shown in Figure 1A.

Table 2.

Effects of 24 h, 48 h, 6 day exposures to PCP on IL-1β secretion from MD-PBMCS.

| 24 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in pg/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[PCP] µM |

F209 | F239 | F241 | F243 |

| 0 | 647±26 | 5139±355 | 978±80 | 660±28 |

| 0.05 | 879±267 | 6705±1112 | 3260±276* | 521±107 |

| 0.1 | 851±61* | 5031±256 | 2591±377* | 546±21* |

| 0.25 | 740±16* | 7998±1992 | 3107±150* | 431±45* |

| 0.5 | 594±37 | 4731±188 | 2723±262* | 767±101 |

| 1 | 872±21* | 4764±394 | 2938±369* | 619±37 |

| 2.5 | 1258±42* | 7401±700* | 1373±93* | 806±90 |

| 5 | 1115±53* | 9151±751* | 2446±109* | 1291±247* |

| 48 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[PCP] µM |

F209 | F239 | F241 | F243 |

| 0 | 2791±128 | 2523±325 | 1220±123 | 427±192 |

| 0.05 | 2509±583 | 4506±917 | 2029±574 | 1445±1694 |

| 0.1 | 1936±87* | 4478±2370 | 2842±266* | 770±281 |

| 0.25 | 2233±115* | 3590±437* | 2868±45* | 411±19 |

| 0.5 | 2824±169 | 6251±389* | 8385±857* | 1591±475* |

| 1 | 1727±83* | 4996±1204 | 1224±221 | 1126±198* |

| 2.5 | 1494±53* | 4223±30* | 3295±463* | 1226±48* |

| 5 | 1654±72* | 4884±265* | 3306±32* | 1349±57* |

| 6day | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[PCP] µM |

F209 | F239 | F241 | F243 |

| 0 | 1559±68 | 2862±185 | 450±43 | 471±33 |

| 0.05 | 1338±176 | 2769±274 | 604±401 | 641±145 |

| 0.1 | 1554±35 | 3102±185 | 1149±188* | 669±95 |

| 0.25 | 1820±56* | 2412±157* | 910±194* | 571±97 |

| 0.5 | 2111±75* | 2979±108 | 1914±199* | 1100±106* |

| 1 | 1982±13* | 3618±243* | 2577±867 | 1310±166* |

| 2.5 | 1960±97* | 4042±390* | 1441±98* | 2290±369* |

| 5 | 1934±80* | 4275±526* | 2252±115* | 3631±14* |

Values are mean±S.D. of triplicate determinations.

Indicates a significant change in secretion compared to control cells (cells treated with vehicle alone), p<0.05

Figure 1.

Effects of 24 h, 48 h and 6 day exposures to PCP on IL-1β secretion from MD-PBMCs, and PBMCs. A) MD-PBMCs exposed to 0.05–5µM PCP (donor F241); B) PBMCs exposed to 0.05–5µM PCP (donor F197)

Effects of PCP Exposures on Secretion of IL-1β PBMCs

Table 3 shows the results of exposing PBMCs from 4 individual donors to 0–5 µM, PCP for 24 h, 48 h, and 6 d on the secretion of IL-1β. When PBMCs were exposed to PCP for 24 h, there were statistically significant increases in IL-1β secretion induced at 5 µM and 1 µM concentrations of PCP for all donors. The fold increases were 2.7 (F197), 2.2 (F211), 2.6 (F214), and 13 (F238) at 5 µM PCP compared to the secretion levels of the control after 24 hours. The effects of 48 h and 6 d exposure to PCP were similar to those seen at 24 h. Figure 1B shows the results from a representative experiment at all three time points.

Table 3.

Effects of 24 h, 48 h, 6 day exposures to PCP on IL-1β secretion from PBMCs.

| 24 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in pg/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[PCP] µM |

F197 | F211 | F214 | F238 |

| 0 | 2267±199 | 1707±58 | 915±135 | 417±26 |

| 0.05 | 2051±187 | 1683±354 | 1054±245 | 472±10 |

| 0.1 | 2482±340 | 2950±73* | 838±74 | 524±21* |

| 0.25 | 3058±11* | 2269±287 | 948±56 | 445±43 |

| 0.5 | 1352±101* | 1878±22* | 1021±31 | 448±16 |

| 1 | 3058±171* | 2011±99* | 1249±63* | 493±10* |

| 2.5 | 4247±474* | 3850±311* | 1887±7* | 620±42* |

| 5 | 6175±196* | 3169±279* | 2407±205* | 5541±22* |

| 48 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[PCP] µM |

F197 | F211 | F214 | F238 |

| 0 | 1310±315 | 2083±73 | 612±50 | 729±24 |

| 0.05 | 1532±202 | 3305±114* | 1317±221* | 978±182 |

| 0.1 | 2324±239* | 2956±401 | 1128±87* | 1126±16* |

| 0.25 | 2426±530* | 2807±87* | 2544±184* | 1820±42* |

| 0.5 | 2495±215* | 4093±280* | 3201±301* | 1091±105* |

| 1 | 2019±281* | 3870±87* | 2360±207* | 968±82* |

| 2.5 | 1894±161 | 4374±312* | 3225±148* | 1308±101* |

| 5 | 3343±222* | 4907±88* | 3438±378* | 1357±50* |

| 6day | Interleukin 1 b eta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[PCP] µM |

F197 | F211 | F214 | F238 |

| 0 | 1208±151 | 1074±118 | 879±23 | 736±220 |

| 0.05 | 1867±93* | 1620±132* | 1126±144 | 638±71 |

| 0.1 | 2180±214* | 1243±51 | 1162±20* | 797±132 |

| 0.25 | 2513±259* | 1326±31 | 2674±15* | 715±49 |

| 0.5 | 2458±151* | 1581±55* | 3034±180* | 1102±51 |

| 1 | 5422±380* | 1773±46* | 2918±85* | 2069±183* |

| 2.5 | 4898±250* | 1750±153* | 3209±154* | 2297±159* |

| 5 | 8105±97* | 1693±134* | 4456±94* | 3191±140* |

Values are mean±S.D. of triplicate determinations.

Indicates a significant change in secretion compared to control cells (cells treated with vehicle alone), p<0.05

Effects of DDT Exposures on Secretion of IL-1β by NK cells

The results of exposing NK cells to 0, 0.025,.05 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1,, and 2.5 µM DDT for 24 h, 48 h, and 6 d on the secretion of IL-1β are summarized in Table 4. 24 h exposures to DDT caused significant increases in IL-1β secretion from NK cells of 3 of the 4 donors, while the fourth donor was unaffected by exposures. However, after 48 h the donor that had shown no significant increases in IL-1β secretion at 24 h now showed a 1.5 fold increase when exposed to 1 µM DDT. Thus, all donors showed an increase in IL-1β secretion after exposure to at least one concentration of DDT within 48 h.

Table 4.

Effects of 24 h, 48 h, 6 day exposures to DDT on IL1β secretion from NK cells.

| 24 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in pg/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[DDT] µM |

KB188 | KB192 | KB194 | KB196 |

| 0 | 39769±5081 | 104±23 | 332±37 | 251±19 |

| 0.025 | 58589±10393 | 137±39 | 155±19* | 208±3 |

| 0.05 | 43000±11533 | 261±14* | 375±32 | 194±5* |

| 0.1 | 45256±5198 | 98±18 | 329±65 | 188±1* |

| 0.25 | 50051±5757 | 77±4 | 301±15 | 199±12* |

| 0.5 | 41692±8240 | 112±63 | 331±8 | 213±9 |

| 1 | 44051±9959 | 95±16 | 333±76 | 208±24 |

| 2.5 | 32795±10276 | 282±24* | 807±35* | 370±10* |

| 48 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[DDT] µM |

KB188 | KB192 | KB194 | KB196 |

| 0 | 54415±1594 | 116±7 | 1027±75 | 303±21 |

| 0.025 | 79000±3581* | 148±20 | 623±43* | 241±45 |

| 0.05 | 73414±5891* | 87±3* | 723±30* | 365±24* |

| 0.1 | 66929±2278* | 125±17 | 878±37 | 342±37 |

| 0.25 | 59975±3274 | 163±12* | 1160±13 | 325±53 |

| 0.5 | 51317±2598 | 95±6* | 598±28* | 296±39 |

| 1 | 79610±4146* | 118±31 | 669±47* | 157±84 |

| 2.5 | 44585±737* | 265±13* | 1178±81 | 132±42* |

| 6day | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[DDT] µM |

KB188 | KB192 | KB194 | KB196 |

| 0 | 74828±2802 | 94±6 | 621±12 | 182±8 |

| 0.025 | 82052±2853* | 137±18* | 610±40 | 200±4* |

| 0.05 | 73649±1074 | 143±0.7* | 394±29* | 193±23 |

| 0.1 | 69711±1219 | 139±0.7* | 598±14 | 220±9* |

| 0.25 | 57525±1531* | 158±13* | 550±47 | 154±50 |

| 0.5 | 78921±2280 | 105±3 | 470±49* | 175±7 |

| 1 | 73588±2799 | 103±8 | 484±6* | 183±4 |

| 2.5 | 67169±2843* | 142±7* | 379±13* | 169±7 |

Values are mean±S.D. of triplicate determinations.

Indicates a significant change in secretion compared to control cells (cells treated with vehicle alone), p<0.05

Effects of DDT Exposures on Secretion of IL-1β by MD-PBMCs

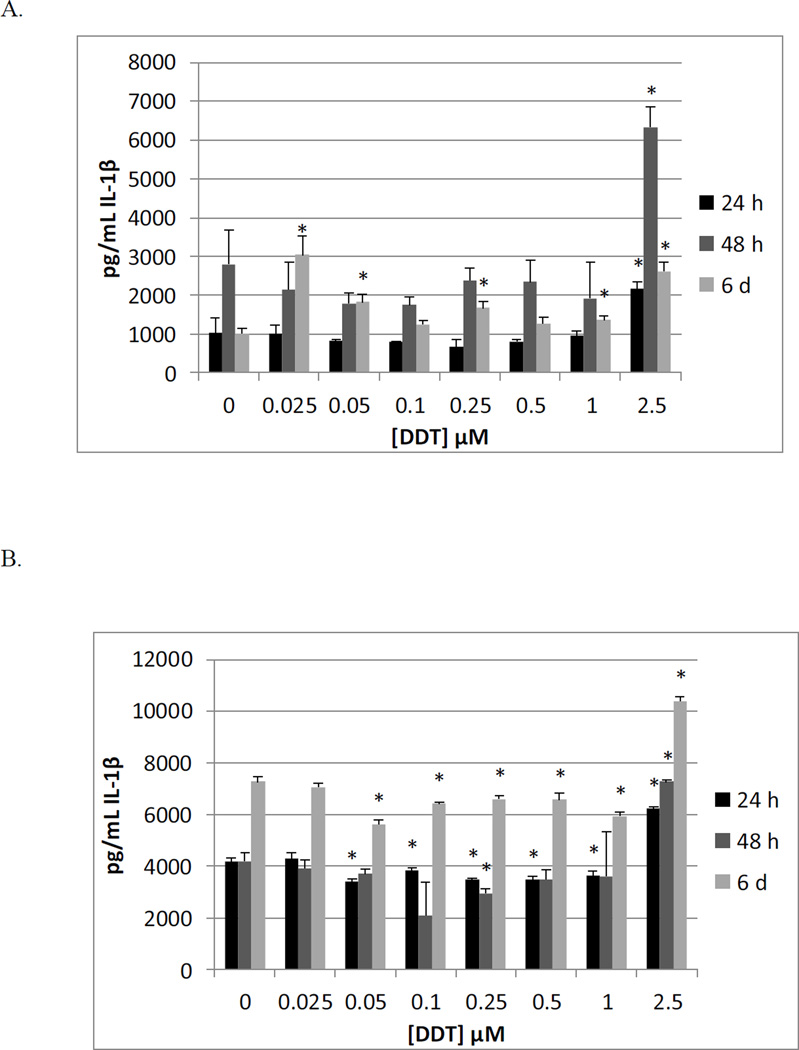

Table 5 shows the effects of exposing MD-PBMCs from 4 individual donors to 0 – 2.5 µM DDT for 24 h, 48 h, and 6 d on the secretion of IL-1β. Significant increases (2 fold) in IL-1β secretion were shown in three donors, at 2.5 µM (F245, F281, F288). Significant decreases in IL-1β secretion were seen at several DDT concentrations in donor F287. At 48 h, all donors exhibited increased IL-1β secretion with exposure to at least on concentration of DDT. 6d exposures to DDT showed effects similar to those seen at 48 h. Figure 2A shows the effects of 24 h, 48 h, and 6 d exposures of MD-PBMCs to DDT from a representative donor.

Table 5.

Effects of 24 h, 48 h, 6 day exposures to DDT on IL-1β secretion from MD-PBMCs.

| 24 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in pg/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[DDT] µM |

F245 | F281 | F287 | F288 |

| 0 | 1020±380 | 2333±764 | 1846±239 | 1326±54 |

| 0.025 | 1016±218 | 2295±518 | 1171±296* | 1452±134 |

| 0.05 | 821±39 | 1984±484 | 941±174* | 1944±1045 |

| 0.1 | 795±27 | 1836±43 | 1030±52* | 1340±157 |

| 0.25 | 661±201 | 2601±952 | 917±176* | 1157±39* |

| 0.5 | 802±56 | 2667±511 | 648±98* | 1305±9 |

| 1 | 955±119 | 2727±109 | 732±59* | 1876±217* |

| 2.5 | 2158±183* | 4951±128* | 699±29* | 2676±202* |

| 48 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[DDT] µM |

F245 | F281 | F287 | F288 |

| 0 | 2769±874 | 2697±359 | 653±116 | 1409±139 |

| 0.025 | 2151±707 | 2017±416 | 688±80 | 1309±56 |

| 0.05 | 1793±249 | 2496±191 | 547±241 | 1283±109 |

| 0.1 | 1753±205 | 2322±283 | 778±250 | 1120±86* |

| 0.25 | 2387±318 | 2572±139 | 724±81 | 1246±178 |

| 0.5 | 2346±558 | 2544±334 | 1240±334 | 1289±63 |

| 1 | 1915±944 | 2607±750 | 647±12 | 1508±173 |

| 2.5 | 6338±514* | 5919±1239* | 1372±69* | 3243±82* |

| 6day | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[DDT] µM |

F245 | F281 | F287 | F288 |

| 0 | 1015±142 | 1883±77 | 518±7 | 561±13 |

| 0.025 | 3035±495* | 2765±139* | 736±406 | 666±56 |

| 0.05 | 1826±210* | 3340±157* | 510±10 | 488±47 |

| 0.1 | 1241±117 | 2105±262 | 944±356 | 589±51 |

| 0.25 | 1665±180* | 2870±67* | 533±107 | 595±68 |

| 0.5 | 1266±161 | 2123±85* | 486±42 | 675±58 |

| 1 | 1365±87* | 2815±225* | 1112±35* | 738±37* |

| 2.5 | 2607±247* | 3815±96* | 495±6* | 1185±43* |

Values are mean±S.D. of triplicate determinations.

Indicates a significant change in secretion compared to control cells (cells treated with vehicle alone), p<0.05

Figure 2.

Effects of 24 h, 48 h and 6 day exposures to DDT on IL-1β secretion from MD-PBMCs, and PBMCs. A) MD-PBMCs exposed to 0.025–2.5µM DDT (donor F245); B) PBMCs exposed to 0.025–2.5µM DDT (donor F229).

Effects of DDT Exposures on Secretion of IL-1β by PBMCs

The effects of exposing PBMCs from 5 individual donors to 0, 0.025, .05 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2. 5 µM DDT for 24 h, 48 h, and 6 d on the secretion of IL-1β are shown in Table 6. At 48 h of exposure to DDT, all donors showed a significant increase in IL-1β secretion at the 2.5 µM concentration. Results from a representative donor are shown in Figure 2B.

Table 6.

Effects of 24 h, 48 h, 6 day exposures to DDT on IL-1β secretion from PBMCs.

| 24 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in pg/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[DDT] µM |

F197 | F201 | F220 | F229 |

| 0 | 2113±195 | 3233±155 | 1930±44 | 4177±121 |

| 0.025 | 3008±348* | 3486±261 | 1901±66 | 4303±336 |

| 0.05 | 1300±156* | 2668±189* | 1887±87 | 3419±73* |

| 0.1 | 2238±136 | 3304±234 | 2002±205 | 3847±78* |

| 0.25 | 1081±83* | 2562±111* | 1945±100 | 3478±76* |

| 0.5 | 1300±31* | 3028±130 | 1800±157 | 3471±146* |

| 1 | 1425±219* | 3033±813 | 2351±176* | 3639±180* |

| 2.5 | 3477±79* | 4295±590 | 3162±66* | 6216±64* |

| 48 h | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[DDT] µM |

F197 | F201 | F220 | F229 |

| 0 | 2257±211 | 3028±354 | 2242±303 | 4182±312 |

| 0.025 | 3118±723 | 2462±299 | 1833±296 | 3919±335 |

| 0.05 | 3239±301 | 1114±80* | 2030±184 | 3699±176 |

| 0.1 | 2342±804 | 2878±194 | 1985±105 | 2096±1272 |

| 0.25 | 2739±329 | 3597±1022 | 2667±446 | 2951±182* |

| 0.5 | 2494±102 | 2960±55 | 2773±120 | 3487±346 |

| 1 | 2242±185 | 3312±166 | 2091±79 | 3607±1702 |

| 2.5 | 3438-277* | 4844±185* | 3530±229* | 7263±92* |

| 6day | Interleukin 1 beta secreted in ng/mL (mean±S.D.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

[DDT] µM |

F197 | F201 | F220 | F229 |

| 0 | 1463±104 | 1653±61 | 3621±268 | 7276±187 |

| 0.025 | 2327±709 | 1884±116 | 2693±413* | 7061±172 |

| 0.05 | 1851±162* | 2056±168* | 3020±58 | 5632±157* |

| 0.1 | 2442±691 | 1438±226 | 1629±932 | 6428±43* |

| 0.25 | 1884±1120 | 1916±43* | 3052±50 | 6592±142* |

| 0.5 | 1179±115* | 1889±155 | 3027±64 | 6575±269* |

| 1 | 1966±1117 | 2169±65* | 3132±201 | 5925±164* |

| 2.5 | 1851±293 | 2534±57* | 4433±109* | 10383±162* |

Values are mean±S.D. of triplicate determinations.

Indicates a significant change in secretion compared to control cells (cells treated with vehicle alone), p<0.05

Effects of PCP Exposures on Secretion of IL-1βeta by PBMCS treated with Selective Enzyme Inhibitors

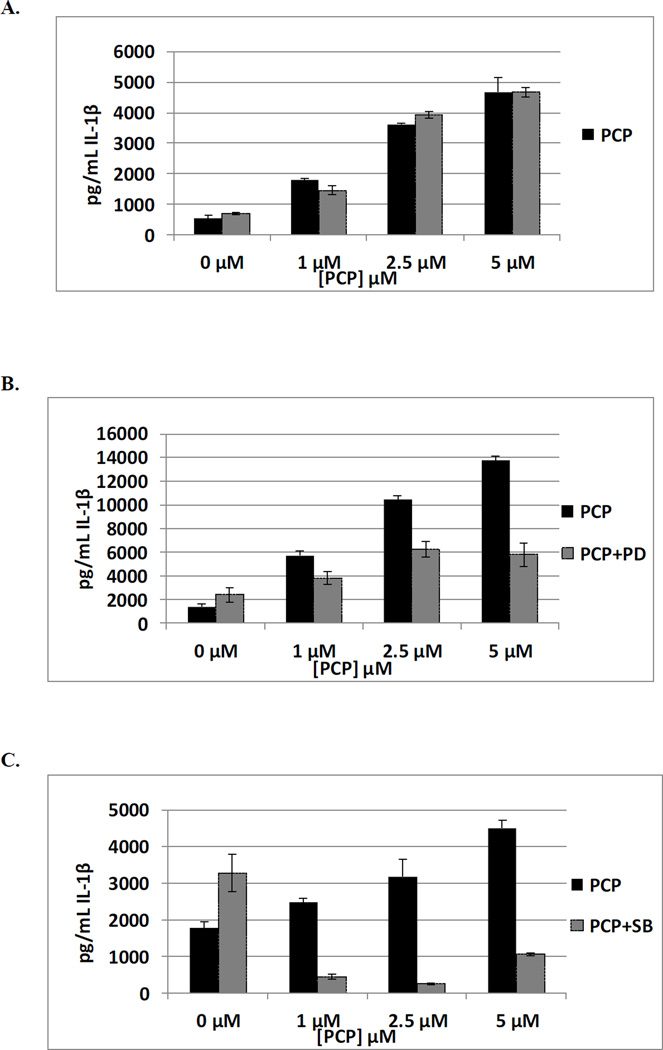

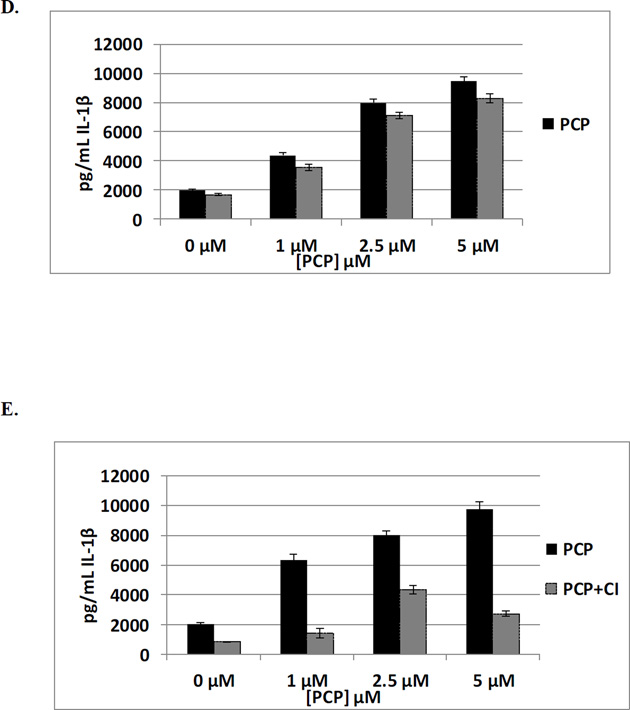

NFκB Inhibitor (BAY 11-7085)

The effects of exposures to 1, 2.5 and 5 µM PCP on secretion of IL-1β from PBMCs where NFκB was inhibited with BAY 11–7085 (0.325 µM) are shown in Table 7. In some donors inhibition of the NFκB pathway slightly increased the ability of PCP to stimulate IL-1β secretion from PBMCs and in other donors slightly decreased the effect of PCP. For instance cells from donor F317 show 9, 7, and 3 fold increases when PBMCs are exposed to 5, 2.5, and 1µM PCP in the absence of the NFκB inhibitor. When the inhibitor is present PCP exposures result in 7, 5 and 1 fold increases in IL-1β secretion. These results suggest that NFκB may play a small role in PCP’s ability to stimulate the secretion of IL-1β by PBMCs. Data from a representative experiment are shown in Figure 3A.

Table 7.

Effects of 24 h exposure to PCP +/− Pathway inhibitors on IL-1β secretion from PBMCs.

| NFκB Inhibitor (BAY 11–7085) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | Interleukin 1-βeta secreted in pg/mL (mean±S.D.) | ||||

|

[PCP] µM |

F-317 | F-318 | F-319 | F-320 | |

| 0 | 528±93 | 37±7 | 1002±79 | 4611±138 | |

| 0 + BAY | 698±27 | 90±9 | 75±6 | 4881±217 | |

| 1 | 1783±58* | 139±4* | 1543±126* | 4169±315 | |

| 1+ BAY | 1459±161** | 372±54** | 164±16** | 4201±201 | |

| 2.5 | 3614±44* | 206±13* | 2154±80* | 5677±208* | |

| 2.5 + BAY | 3934±123** | 462±41** | 166±9** | 5814±189** | |

| 5 | 4733±489* | 232±10 * | 1442±215* | 8582±388* | |

| 5 + BAY | 4682±152** | 431±70** | 138±12** | 7874±34** | |

| MEK Inhibitor (PD98059) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | Interleukin 1-βeta secreted in pg/mL (mean±S.D.) | ||||

|

[PCP] µM |

F-317 | F318 | F319 | F-320 | |

| 0 | 1246±104 | 102±5 | 158±172 | 1381±239 | |

| 0 + MEK | 1731±76** | 90±10 | 674±55 | 2380±593 | |

| 1 | 3448±44* | 358±57* | 419±27* | 5724±334* | |

| 1+ MEK | 1485±325 | 453±7** | 263±98 | 3790±535** | |

| 2.5 | 5076±208* | 588±25* | 778±68* | 10442±361* | |

| 2.5 + MEK | 2925±160** | 746±19** | 1814±65** | 6247±629** | |

| 5 | 7668±368* | 903±30* | 1158±119* | 13770±308* | |

| 5 + MEK | 8969±142** | 523±32** | 1606±151** | 5775±973** | |

| p38 Inhibitor (SB202190) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | Interleukin 1-βeta secreted in pg/mL (mean±S.D.) | ||||

|

[PCP] µM |

F-317 | F-318 | F-319 | F-320 | |

| 0 | 2191±77 | 22.5±2 | 1772±169 | 5209±37 | |

| 0 + p38 | 883±66 | 7±2 | 3282±520 | 2376±154 | |

| 1 | 5404±367* | 127±12* | 2469±114* | 6348±472* | |

| 1+ p38 | 2368±622 | 22±2** | 434±68 | 3107±261** | |

| 2.5 | 8851±21* | 194±15* | 3180±461* | 8344±507* | |

| 2.5 + p38 | 1070±98 | 21±1** | 243±23 | 749±74 | |

| 5 | 11390±304* | 237±47* | 4513±212* | 10362±638* | |

| 5 + p38 | 557±113 | 31±3** | 1056±27 | 351±71 | |

| JNK Inhibitor (B178D3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | Interleukin 1-βeta secreted in pg/mL (mean±S.D.) | ||||

|

[PCP] µM |

F-317 | F318 | F319 | F-320 | |

| 0 | 1990±73 | 55±8 | 168±41 | 7622±372 | |

| 0 + JNK | 1710±75 | 89±4 | 210±16 | 7043±115 | |

| 1 | 4397±204* | 364±11* | 561±66* | 7721±343 | |

| 1+ JNK | 3579±214** | 463±56** | 828±98** | 8371±465** | |

| 2.5 | 7995±223* | 524±24* | 396±72* | 12300±107* | |

| 2.5 + JNK | 7122±215** | 543±71** | 842±104** | 11344±596** | |

| 5 | 9509±278* | 368±30* | 438±50* | 16486±490* | |

| 5 + JNK | 8323±295** | 455±43** | 1123±207** | 14830±729** | |

| Caspase 1 Inhibitor | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | Interleukin 1-βeta secreted in pg/mL (mean±S.D.) | ||||

|

[PCP] µM |

F-317 | F318 | F319 | F-320 | |

| 0 | 2014±108 | 64±3 | 1920±135 | 7169±294 | |

| 0 + CI | 856±29 | 58±1 | 180±34 | 2354±299 | |

| 1 | 6338±411* | 430±1* | 2376±114* | 6825±71* | |

| 1+ CI | 1384±330** | 411±15** | 207±103 | 2043±111 | |

| 2.5 | 8009±300* | 423±29* | 3280±223* | 9724±549* | |

| 2.5 + CI | 4352±272** | 270±8 ** | 107±49 | 3386±182** | |

| 5 | 9736±565* | 375±3 * | 3308±21* | 13066±604* | |

| 5 + CI | 2718±187** | 243±10** | 1207±103** | 3446±58** | |

Values are mean±S.D. of triplicate determinations.

indicates a significant increase compared to no PCP (0), p<0.05

indicates a significant increase compared to no PCP + inhibitor, p<0.05

Figure 3.

Effects of 24 h exposure to 0.5, 1, and 2.5 µM PCP on IL-1β secretion from PBMCs pre-treated with selective enzyme inhibitors. A) NFκB Inhibitor (BAY 11-7085) (donor F317); B) MEK Inhibitor (PD98059) (donor F320); C) p38 Inhibitor (SB202190) (donor F3179; D) JNK inhibitor (B178D3) (donor F317; E.) Caspase 1(F317)

Mitogen activated protein kinase kinase for ERK1/2 (MEK) Inhibitor (PD98059)

PCP-induced stimulation of IL-1β secretion in PBMCs pre-treated with the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (50 µM) is shown in Table 7. Cells from all donors exposed to 5 µM PCP showed increases in IL-1β secretion. This PCP-stimulated secretion was diminished in each donor when the ERK1/2 pathway was inhibited by PD98059. There was a decrease in PCP-stimulated IL-1β secretion at 2.5 and 1 µM PCP in most donors For instance cells from donor F320 showed 10, 7.6 and 4.1 fold increases with 5, 2.5, and 1µM in the absence of the MEK inhibitor. With the MEK inhibitor, these same concentrations of PCP caused increases of only 2.4, 2.6, and 1.6 fold. These results indicate that the ERK1/2 pathway may play a significant role in PCP’s ability to stimulate secretion of IL-1β in PBMCs (Figure 3B).

p38 Inhibitor (SB202190)

Table 7 also shows the effects of exposures to 1, 2.5 and 5 µM PCP on secretion of IL-1β from PBMCs where p38 has been inhibited with SB202190. Inhibition of p38 tended to greatly decrease or completely block the PCP-induced increases in secretion of IL-1β. Figure 3C (representative data from F319) shows 2.5, 1.8 and 1.4 fold increases when PBMCs are exposed to 1, 2.5 and 5 µM PCP in the absence of p38 inhibitor. When the inhibitor is present, these same PCP exposures result in a complete block in IL-1β secretion. Thus, the p38 MAPK pathway appears to be very important in PCP-stimulated IL-1β secretion.

JNK Inhibitor (BI78D3)

The effects of exposures to 1, 2.5 and 5 µM PCP on secretion of IL-1β from PBMCs where JNK is inhibited by BI78D3 (0.05 µM) are shown in Table 7. Cells exposed to PCP showed similar levels of IL-1β secretion in the presence and absence of the JNK inhibitor. This indicates that JNK is not needed for PCP to increase IL-1β secretion from PBMCs (Figure 3D).

Caspase 1 Inhibitor

The results of exposures to 1, 2.5 and 5 µM PCP on secretion of IL-1β from PBMCs where Caspase 1 has been inhibited by capase 1 inhibitor (0.325 µM) are shown in Table 7. Inhibition of Caspase 1 had only minimal effects on PCP-induced IL-1β secretion. Figure 4D (representative data from F317), shows 3, 4, and 5 fold increases when PBMCs are exposed to 1, 2.5 and 5 µM PCP in the absence of C1 inhibitor. When the inhibitor is present, these same PCP exposures result in 1.6, 5.1, and 3.2 fold increases in IL-1β secretion. These results suggest that Caspase 1 may play a small role in PCP’s ability to stimulate secretion of IL-1β.

DISCUSSION

Both PCP and DDT are found at significant level in human blood samples, with PCP being as high as 5 µM (Cline et al., 1989) and DDT as high as 260 nM (Koepke et al., 2004). PCP exposure has been associated with kidney cancer, lymphoma, and myeloma (Demers et al., 2006) while DDT exposure is linked to increased incidences of liver, pancreatic, breast, and testicular cancers as well as leukemia (Eskanazi et al., 2009; Cohn et al., 2007; Snedeker & Stapleton, 2009). Studies have shown that the tumor binding (Hurd et al., 2012; Hurd-Brown et al., 2013) and lysing function (Reed et al., 2004; Nnodu and Whalen, 2008) of human NK lymphocytes as well as their expression of important cell surface proteins (Hurd et al., 2012; Hurd-Brown et al., 2013) is decreased by ex vivo exposure to PCP and DDT. IL-1β in its role as a pro-inflammatory cytokine is a master regulator of the immune response (Sahoo et. al, 2011; Dinarello, 1996). Dysregulation of its levels can lead to loss of immune competency (decreased levels) or chronic inflammation (increased levels) (Dinarello 1996; Braddock and Quinn, 2004; Dinarello, 2004). The current study examined whether PCP and/or DDT exposure altered secretion of this important cytokine from increasingly complex preparations of human immune cells and results indicated that both compounds were able to increase IL-1β secretion dependent on length and concentration of the exposure.

The immune cell preparations used in this study ranged from a preparation that was predominantly NK lymphocytes to PBMCs which were a combination of lymphocytes and monocytes. Additionally, a preparation of T and NK lymphocytes (MD-PBPMCs) was also examined. When these 3 cell preparations were exposed to PCP there was no major effect on the viability of the immune cells, which indicated that the effects seen on IL-1β secretion were not due cell death. NK cells tended to show decreases in IL-1β secretion as the highest concentration of PCP (5 µM) and increases at lower concentrations (the specific concentration at which increases were seen varied among donors). However, when the more complex preparations (MD-PBMCs and PBMCs) were exposed to PCP there were increases in IL-1β secretion induced by the higher exposure concentrations after 24 h. For instance all donors tested showed increases at the 5 µM concentration after 24 h in MD-PBMCs and at the 5–1 µM concentrations in PBMCs. In PBMCs, concentrations as low as 0.1 µM caused significant increases (approximately 2 fold) in secretion after either 24 or 48 h of exposure in cells from all donors and the lowest concentration examined (0.05 µM) also caused significant increases in 3 of the 4 donors at one or more length of exposure. The highest fold increase seen with PCP exposure was 13 fold after a 24 h exposure to 5 µM PCP in PBMCs. Thus, all cell preparations tested showed alterations in IL-1β secretion in response to PCP exposures. However, preparations with T cells (MD-PBMCs) and with monocytes (PBMCs) had a different pattern of response than was seen with NK cells. This suggests that the more complex milieu of cells, that more closely approximates physiological conditions, responds to a wide range of PCP exposures by increasing secretion of the pro-inflammatory IL-1β.

DDT exposures caused the same general effect in all three cell preparations. NK cells, MD-PBMCs, and PBMCs from all donors showed significant increases in IL-1β secretion with exposures to one or more PCP concentration at one or more length of incubation. Increases tended to be approximately 2 fold and usually persisted out to 6 days of exposure. Increases most commonly occurred at the 2.5 µM exposure, but in some donors occurred at the lowest concentration of 0.025 µM.

Signaling pathways involved in regulating the release of IL-1β from immune cells include Caspase I, NFκB and MAPKs (ERK1/2, p38, and JNK) (Lopez-Castejon & Brough, 2011; Gaestel et al., 2009). PCP caused very robust increases in IL-1β secretion from PBMCs and thus, this PCP-induced secretion was examined for the involvement of the above mentioned signaling pathways. The data indicated that Caspase 1, NFκB, and JNK played little to no role in the ability of PCP to stimulate IL-1β release from immune cells, while both ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK pathways appeared to be needed for the effect. For example a 4 fold increase in IL-1β secretion stimulated by 1 µM PCP was dropped to 1.6 fold when the ERK1/2 pathway was inhibited with PD98059. Likewise inhibition of the p38 pathway resulted in a loss of PCP-induced IL-1β secretion. Previous studies on exposure to PCP have shown an association of PCP exposures with a number of cancers (Demers et al., 2006; Cooper & Jones, 2008) and increased IL-1β has been shown to promote cancer development (Balkwill & Mantovani 2001; Coussens & Werb, 2002). Thus, if PCP has effects on IL-1β secretion in exposed individuals, similar to those seen with a complex ex vivo system, the increased risk of cancer might be at least in part due to its capacity to increase IL-1β levels.

Both PCP and DDT showed variations in their effects on IL-1β secretion (specific lengths and concentrations of exposure) that was donor dependent. The concept of personalized treatment of a number of diseases, most especially cancer (Madureira & de Mello, 2014) has begun to evolve. The results from this study indicate that there may individualized responses to these environmental toxicants, which may be important in assessing risk for a variety of conditions. Additionally, these result indicate that both PCP and DDT may have the capacity to induce “sterile inflammation” (a term used to describe inflammation occurring in the absence of a microorganism) (Chen & Nunez, 2010). The results of the current study indicate that concentrations of PCP and DDT that have been shown to occur in human blood (Cline et al., 1989; Uhl et al., 1986; Koepke et al., 2004; Trejo-Acevedo et al., 2009) lead to elevation of IL-1β ex vivo. Such “sterile inflammation” could worsen multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis (Lucas & Hohlfeld, 1995; Choy & Panayi, 2001) as well as lead to enhanced tumor development and progression (Lewis & Varghese, 2006;Smith & Kang, 2013). The results of the current study indicate that decreasing the levels of exposure to these contaminants, resulting in accompanying decreases in blood levels, may be important in preventing potential increases in the pro-inflammatory cytokine, IL-1β.

In summary, both PCP and DDT cause increased secretion of the seminal pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β from increasingly reconstituted preparations of immune cells. This increased secretion occurs at varying concentrations of the toxicants over several lengths of exposure with the effects varying among donors. The PCP- induced increases in IL-1β secretion (from PBMCs) are largely independent of Caspase 1, NFκB, and JNK signaling activity, but appear to require the p38 MAPK pathway.

Acknowledgments

Grant U54CA163066 from the National Institutes of Health

REFERENCES

- Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological Profile for Pentachlorophenol. Update. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F, Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: back to Virchow? Lancet. 2001;357(9255):539–545. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach TM, Whalen MM. Effects of organochlorine pesticides on interleukin secretion from lymphocytes. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2006;25(11):651–659. doi: 10.1177/0960327106070072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braddock M, Quinn A. Targeting IL-1 in inflammatory disease: new opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004;3:1–10. doi: 10.1038/nrd1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B, Loganathan BG, Owen DA. Chlorophenol concentrations in sediment and mussel tissues from selected locations in Kentucky Lake. Vol. 1. Chrysalis: 2005. pp. 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Second National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. Atlanta, GA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Third National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. 2005. Jul, [Google Scholar]

- Chen GY, Nunez G. Sterile inflammation: sensing and reacting to damage. Nature Reviews/Immunology. 2010;10:826–837. doi: 10.1038/nri2873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy EHS, Panayi GS. Cytokine Pathways and Joint Inflammation in Rheumatoid Arthritis. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344:907–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church LD, Cook GP, McDermott MF. Primer: inflammasomes and interleukin- 1β in inflammatory disorders. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 2008;4:34–42. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli DP. Patterns of pentachlorophenol usage in the United States of America-an overview. In: Rao KR, editor. Pentachlorophenol, chemistry, pharmacology, and environmental toxicology. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1978. pp. 13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Cline RE, Hill RH, Phillips DL, Needham LL. Pentachlorophenol measurements in body fluids of people in log homes and workplaces. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1989;18:475–481. doi: 10.1007/BF01055012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn BA, Wolff MS, Cirillo PM, Sholtz RI. DDT and breast cancer in young women: new data on the significance of age at exposure. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007;115:406–414. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper GS, Jones S. Pentachlorophenol and Cancer Risk: Focusing the Lens on Specific Chlorophenols and Contaminants. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008;116(8):1001. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;26420(6917):860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demers PA, Davies HW, Friesen MC, Hertzman C, Ostry A, Hershler R, et al. Cancer and occupational exposure to pentachlorophenol and tetrachlorophenol. Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:749–758. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sanctis JB, Blanca I, Bianco NE. Secretion of cytokines by natural killer cells primed with interleukin-2 and stimulated with different lipoproteins. Immunology. 1997;90:526–533. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00174.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Therapeutic strategies to reduce IL-1 activity in treating local and systemic inflammation. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2004;4:378–385. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinarello CA. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskenazi B, Chevier J, Rosas LG, Anderson HA, Bornman MS, Bouwman H, Chen A, Cohn BA, deJager C, Henshe DS, Leipzig F, Leipzig JS, Lorenz EC, Snedeker SM, Stapleton D. The Pine River Statement: Human Health Consequences of DDT Use. Environ. Health Perspec. 2009;117:1359–1367. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L, Eigenbrod T, Munoz-Planillo R, Nunez G. The Inflammasome: A Caspase-1 Activation Platform Regulating Immune Responses and Disease Pathogenesis. Nature Immunology. 2009;10:241–247. doi: 10.1038/ni.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaestel M, Kotlyarov A, Kracht M. Targeting innate immunity protein kinase signalling in inflammation. Nature Rev. Drug Disc. 2009;8:480–499. doi: 10.1038/nrd2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisz HN, Dickhut RM, Cochran MA, Fraser WR, Ducklow HW. Melting glaciers: a probable source of DDT to the Antarctic marine ecosystem. Environmental Science & Technology. 2008;42:3958–3962. doi: 10.1021/es702919n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd-Brown T, Udoji F, Martin T, Whalen MM. Effects of DDT and Triclosan on Tumor-cell Binding Capacity and Cell-Surface Protein Expression of Human Natural Killer Cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2013;33:495–502. doi: 10.1002/jat.2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurd T, Walker J, Whalen MM. Pentachlorophenol Decreases Tumor-cell-binding Capacity and Cell-Surface Protein Expression of Human Natural Killer Cells. Journal of Applied Toxicology. 2012;32:627–634. doi: 10.1002/jat.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepke R, Warner M, Petreas M, Cabria A, Danis R, Hernandez-Avila M, Eskenazi B. Serum DDT and DDE levels in pregnant women of Chiapas. Mexico. Arch. Environ. Health. 2004;59:559–565. doi: 10.1080/00039890409603434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis A, Varghese S. Interleukin-1 and cancer progression: the emerging role of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist as a novel therapeutic agent in cancer treatment. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2006;12:1–12. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-4-48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loganathan BG. Global contamination trends of persistent organic chemicals: An overview. In: Loganathan BG, Lam PKS, editors. Global Contamination Trends of Persistent Organic Chemicals. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2012. pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Castejon G, Brough D. Understanding the mechanism of IL-1b secretion. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2011;22:189–195. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas K, Hohlfeld R. Different aspects of cytokines in the immunopathology of multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1995;45:S4–S5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.6_suppl_6.s4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madureira P, de Mello RA. BRAF and MEK gene rearrangements in melanoma: implications for targeted therapy. Mol Diagn Ther. 2014;18:285–291. doi: 10.1007/s40291-013-0081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F, Tschopp J. Inflammatory caspases and inflammasomes: master switches of inflammation. Cell Death and Differentiation. 2007;14:10–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TP, Zehnter I, Hofmann B, Zaisserer J, Burkhart J, Rapp S, Weinauer F, Schmitz J, Iller WE. Filter Buffy Coats (FBC): A source of peripheral blood leukocytes. J. Immunol. Meth. 2005;307:150–166. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nnodu U, Whalen MM. Pentachlorophenol decreases ATP levels in human natural killer cells. J. Appl.Toxicol. 2008;28:1016–1020. doi: 10.1002/jat.1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numerof RP, Kotik AN, Dinarello CA, Mier JW. Pro-interleukin-1 beta production by a subpopulation of human T cells, but not NK cells, in response to interleukin-2. Cell Immunol. 1990;130:118–128. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(90)90166-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson DG, Jr, Wong LY, Turner WE, Caudill SP, Dipietro ES, McClure PC, Cash TP, Osterloh JD, Pirkle JL, Sampson EJ, Needham LL. Levels in the U. S. population of those persistent organic pollutants (2203–2004) included in the Stockholm Convention or in other long-range trans-boundary air pollution agreements. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009;43:1211–1218. doi: 10.1021/es801966w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed A, Dzon L, Loganathan BG, Whalen MM. Immunomodulation of human natural killer cell cytotoxic function by organochlorine pesticides. Human and Experimental Toxicology. 2004;23:463–471. doi: 10.1191/0960327104ht477oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahoo M, Ceballos-Olvera I, del Barrio L, Re F. Role of the Inflammasome, IL-1β, and IL-18 in Bacterial Infections. The Scientific World JOURNAL. 2011;11:2037–2050. doi: 10.1100/2011/212680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi C, Pamer EG. Monocyte recruitment during infection and inflammation. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2011;11:762–774. doi: 10.1038/nri3070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith HA, Kang Y. The metastasis-promoting roles of tumor-associated immune cells. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2013;91:411–429. doi: 10.1007/s00109-013-1021-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snedeker SM, Stapleton D. The Pine River Statement: Human Health Consequences of DDT Use. Environ. Health Perspec. 2009;117:1359–1367. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson BG, Hallberg T, Nilsson A, Schütz A, Hagmar L. Parameters of immunological competence in subjects with high consumption of fish contaminated with persistent organochlorine compounds. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health. 1994;65:351–358. doi: 10.1007/BF00383243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaan P, Knoell D, Helsper F, Wewers M. Sequential Processing of Human ProIL-1β by Caspase-1 and Subsequent Folding Determined by a Combined In Vitro and In Silico Approach. Pharmaceutical Research. 2001;18:1083–1090. doi: 10.1023/a:1010958406364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trejo-Acevedo A, Diaz-Barriga F, Carrizales L, Dominguez G, Costilla R, Ize-Lema I, Yarto-Ramirez M, Gavilan-Garcia A, Mejia-Saavedra JJ, Perez-Maldonado IN. Exposure assessment of persistent organic pollutants and metals in Mexican children. Chemosphere. 2009;74:974–980. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton JW, McCally M, Houlihan J. Biomonitoring of industrial pollutants: Health and policy implications of the chemical body burden. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:315–323. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50167-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turusov V, Rakitsky V, Tomatis L. Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT): ubiquity, persistence, and risks. Environmental Health Perspectives, Review. 2002;110:125–128. doi: 10.1289/ehp.02110125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udoji F, Martin T, Etherton R, Whalen MM. Immunosuppressive Effects of Triclosan, Nonylphenol, and DDT on Human Natural Killer Cells In Vitro. J. Immunotoxicol. 2010;7:205–212. doi: 10.3109/15476911003667470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhl S, Schmid P, Schlatter C. Pharmacokinetics of pentachlorophenol in man. Arch. Toxicol. 1986;58:182–186. doi: 10.1007/BF00340979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang YJ, Ho YS, Jeng JH, Su HJ, Lee CC. Different cell death mechanisms and gene expression in human cells induced by pentachlorophenol and its major metabolite, tetrachlorohydroquinone. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2000;128:173–188. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00194-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]