Abstract

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is the leading cause of kidney failure in the world. To understand important mechanisms underlying this condition, and to develop new therapies, good animal models are required. In mouse models of type 1 diabetes, the DBA/2J strain has been shown to be more susceptible to develop kidney disease than other common strains. We hypothesized this would also be the case in type 2 diabetes. We studied db/db and wild-type (wt) DBA/2J mice and compared these with the db/db BLKS/J mouse, which is currently the most widely used type 2 DN model. Mice were analyzed from age 6 to 12 wk for systemic insulin resistance, albuminuria, and glomerular histopathological and ultrastructural changes. Body weight and nonfasted blood glucose were increased by 8 wk in both genders, while systemic insulin resistance commenced by 6 wk in female and 8 wk in male db/db DBA/2J mice. The urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) was closely linked to systemic insulin resistance in both sexes and was increased ~50-fold by 12 wk of age in the db/db DBA/2J cohort. Glomerulosclerosis, foot process effacement, and glomerular basement membrane thickening were observed at 12 wk of age in db/db DBA/2J mice. Compared with db/db BLKS/J mice, db/db DBA/2J mice had significantly increased levels of urinary ACR, but similar glomerular histopathological and ultrastructural changes. The db/db DBA/2J mouse is a robust model of early-stage albuminuric DN, and its levels of albuminuria correlate closely with systemic insulin resistance. This mouse model will be helpful in defining early mechanisms of DN and ultimately the development of novel therapies.

Keywords: insulin resistance, diabetic nephropathy, kidney injury, albuminuria, genetic background

diabetic nephropathy (DN) is the leading cause of kidney failure in the world with over half of patients in the United States entering the end-stage renal failure (ESRF) program for this reason. It is increasing at alarming rates throughout both the developed and developing worlds predominantly due to the global epidemic increase in type 2 diabetes (33) caused by sedentary lifestyles, diet, and obesity (16). DN generally has a well-defined natural history and initially affects the glomerulus, manifesting as hyperfiltration and microalbuminuria (30–300 mg albumin/24 h) before progressing to macroalbuminuria (>300 mg albumin/ 24 h). Macroalbuminuria usually heralds the start of declining glomerular filtration and associated tubulointerstitial fibrosis. The best current biomarker for kidney involvement in DN is the presence of micro- or macroalbuminuria. These may be helpful in identifying affected kidneys and allow therapies to be started early before established fibrotic kidney disease is present. It is now clear that systemic insulin resistance is closely linked to DN progression in both type 1 (25) and type 2 DN (12), so finding models that mimic this would be beneficial in understanding mechanisms and ultimately identifying therapeutic targets to stop early DN from progressing. To understand the mechanisms underlying DN, it is vital to have good cellular and animal models of DN, but these are currently suboptimal.

In diabetic patients, multiple genetic factors modulate the risk of developing DN (11, 26). Similarly in mice, the susceptibility to kidney injury is influenced by the inbred mouse strain used as have been illustrated in models of type 1 diabetes. At one extreme, the C57BL/6J strain is resistant to DN in the streptozotocin (STZ)-induced and the Ins2+/C96Y (Akita) models of diabetes, as diabetic mice develop only subtle albuminuria with slow advancement of mesangial matrix expansion (13, 14). At the other extreme, the DBA/2J strain displays enhanced susceptibility to DN and develops exaggerated urinary albumin excretion compared with other common inbred mouse strains including C57BL/6J, A/J, and Sv129 in the STZ-induced (13, 28) and the Akita (5, 14) models.

The genetic background also influences the susceptibility to DN in the db/db mouse model, where an autosomal recessive mutation in the Lepr gene (i.e., the diabetogenic db allele) renders mice obese, insulin resistant, and diabetic (7). The phenotypical manifestations of the db allele were first described in the C57BLKS/J (BLKS/J) strain (17), which is a genetic composite between the DN-resistant C57BL/6J and DN-susceptible DBA/2J strains in addition to alleles from at least three other strains including SV129 (22). The db/db BLKS/J mouse is susceptible to DN and develops significant albuminuria by 8 wk of age (2, 6, 23, 30) along with histopathological features of early DN by 12 wk of age, including glomerular enlargement (21, 23) and glomerulosclerosis (6, 21, 23). Despite having >70% of its genome derived from the DN-resistant C57BL/6J strain, the db/db BLKS/J mouse constitutes a robust model of the early changes in human DN (1), and DBA/2J-derived genetic components may be responsible for the susceptibility to DN in this strain. Although the db allele has been introduced in the DBA/2J strain (19), the susceptibility to albuminuric kidney disease and development of DN in the db/db DBA/2J mouse remain to be explored in detail.

Here, we describe the development of early DN in the db/db DBA/2J mouse to investigate the influence of genetic background on the susceptibility to kidney injury during the transition from prediabetes to diabetes in the db/db mouse model. We hypothesize that the DBA/2J strain displays augmented albuminuria as well as histopathological and ultrastructural changes compared with the commonly used BLKS/J strain. Using female and male db/db DBA/2J mice alongside age- and gender-matched lean controls, we characterized the development of metabolic parameters (i.e., body weight, blood glucose, and systemic insulin sensitivity) and the development of kidney injury (i.e., urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio, glomerulosclerosis score, and ultrastructural features). We investigated the effects of genetic background on DN by comparing our findings with a cohort of db/db BLKS/J mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse breeding and housing.

Heterozygous db/wt DBA/2J (D2.BKS(D)-Leprdb/J) breeders were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) to breed female and male db/db mice and lean wild-type (wt) offspring in house. To obtain adequate numbers of lean control mice, both db/wt and wt/wt mice were included in the experiment, hereinafter referred to as wt mice. Data on outcome of breeding are presented in Table 1. Male db/db and heterozygous db/wt BLKS/J (BKS.Cg-Dock7m +/+ Leprdb/J) mice were purchased from Charles River (Calco, Italy).

Table 1.

DBA/2J breeding outcome

| Female | Male | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Litters | 12 | ||

| Mice/litter (mean) | 2.7 | 2.8 | 5.5 |

| Gender (fraction) | 0.49 | 0.51 | 1.00 |

| Genotype (fraction) | |||

| db/db | 0.32 | 0.41 | 0.36 |

| db/wt | 0.52 | 0.44 | 0.48 |

| wt/wt | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.16 |

All mice were housed in a 12:12-h light-dark cycle with free access to standard chow (EURodent Diet 22%, percentage of energy: protein 25.9%, fat 9.3%, carbohydrate 64.8%; LabDiet, St. Louis, MO) and water. All animal procedures were carried out according to the Guidance of the Operation of the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, and all protocols were approved by the Home Office (London, UK).

Characterization of metabolic parameters.

To characterize the early metabolic phenotype of the db/db model, a total of 24 db/db (12 females, 12 males) and 15 wt (8 females, 7 males) DBA/2J mice were kept from 6 and up to 12 wk of age, whereas 6 male db/db and 6 wt BLKS/J mice were kept from 8 to 12 wk of age. Body weight and nonfasted blood glucose were measured biweekly. Blood glucose was measured in tail vein blood using an Accu-Chek Aviva Nano portable glucometer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN).

Systemic insulin sensitivity was assessed by insulin tolerance tests (ITT) at 6, 8, and 12 wk in DBA/2J mice, and at 8 and 12 wk in BLKS/J mice. Briefly, mice were fasted for 6 h with free access to water. Human insulin (Novo Nordisk, Måløv, Denmark) was injected intraperitoneally (ip) at a dose of 0.20 IU/kg in females and 0.50 IU/kg in males, respectively. Blood glucose was measured in tail vein blood before (t = 0 min) and 15, 30, 45, 60, and 90 min after insulin injection using an Accu-Chek Aviva Nano portable glucometer. The applied doses of insulin were empirically determined before ITTs as the dose required to reduce blood glucose by 20-40% from baseline 15 min after ip insulin injection in 8-wk-old wt DBA/2J mice.

By 12 wk of age, mice were fasted for 6 h with free access to water and euthanized by an ip injection of pentobarbital sodium (200 mg/kg). Blood was collected by cardiac puncture, transferred to a heparinized tube, spun, and plasma was stored at −80°C. Plasma insulin and IGF-1 were quantified using an Ultrasensitive Mouse Insulin ELISA kit and Mouse IGF-1 ELISA kit (both from Crystal Chem, Downers Grove, IL), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasma creatinine was measured using the creatinine enzymatic assay as previously described (18). Finally, kidneys were dissected and either snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed for histological and ultrastructural evaluation as described below.

Urine collection and urinary albumin excretion.

To assess urinary albumin excretion, spot urine samples were collected biweekly and stored at −20°C. The urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) was quantified using a Mouse Albumin ELISA Quantification Set (Bethyl Laboratories, Montgomery, TX) and Creatinine Companion kit (Exocell, Philadelphia, PA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Urinary albumin excretion was also assessed by gel electrophoresis. Briefly, urine samples (5 µl/well) and a BSA control (Sigma-Aldrich, Gillingham, UK) of 10 µg/well were separated in 12% Mini-PROTEAN TGX gels and proteins visualized by Coomassie stain using Bio-Safe Coomassie G-250 Stain (both Bio-Rad, Hemel Hempstead, UK).

Glomerular histopathology and ultrastructure.

For histopathological evaluation, dissected kidneys were fixed in 4% formalin at 4°C, dehydrated, embedded in paraffin, and cut at 3 µm before staining with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) and Masson’s trichrome (TRI) stains using kits (both Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Glomerulosclerosis was scored semiquantitatively according to the percentage of the glomerular tuft occupied with PAS-positive and nuclei-free matrix. From each mouse, a minimum of 18 glomeruli were scored according to a 5-point scale using the following criteria: 0, normal glomerulus; 1, up to 25% matrix area; 2, 25–50% matrix area; 3, 50–75% matrix area–focal; and 4, 75–100% matrix area–global.

For immunofluorescence staining, frozen kidneys were cut at ~8 µm using a freezing microtome, and sections were blocked with 5% normal goat serum in 0.3% Triton X-100/PBS before incubation with primary antibodies against nephrin (Acris, Hereford, Germany) and collagen IV (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). All sections were incubated with Alexa Fluor 405- and 488-conjugated secondary antibodies in 3% BSA, 0.3% Triton X-100/PBS, and mounted with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Peterborough, UK) before imaging using a Leica SP5II confocal laser scanning microscope attached to a Leica DMI 6000 inverted epifluorescence microscope with a ×63 oil-immersion objective lens.

For evaluation of glomerular ultrastructure including foot process effacement and glomerular basement membrane thickening, ~1-mm3 cubes from the renal cortex were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at 4°C. Samples were postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) and en bloc stained in 3% aqueous uranyl acetate followed by dehydrated through a graded series of alcohol. Samples were embedded in Epon Resin and thin-sectioned at 70 nm. Digital micrographs were taken on a FEI Tecnai Spirit T12 (120KV) Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM).

Statistical analyses.

Data were modeled and groups compared using linear mixed-effects models in R (version 3.2.1; open source software available at http://www.cran.r.-project.org). Fixed effects (group, age, gender, and strain) and random effects (mouse and litter) were included in the models as found appropriate. Longitudinal variables were analyzed as repeated measurements using the lme function to test for the effect of age and to compare groups, while variables that were independent of age and variables that were measured at one time point only were analyzed using the lmer function. Model residuals and fitted values were tested for normality. In cases of nonnormality, data were log10-transformed before modeling and group comparison. Linear correlation analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism (version 6.05; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Unless stated otherwise, data are presented as means ± SE. Resulting P values are evaluated at a 5% significance level.

RESULTS

Metabolic phenotype of the db/db DBA/2J mouse.

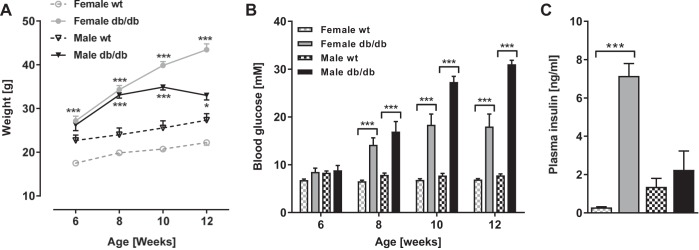

Body weight and nonfasted blood glucose were monitored from 6–12 wk of age in female and male db/db and wt DBA/2J mice to characterize the early development of obesity and hyperglycemia. The body weight was significantly higher in db/db vs. wt females from 6 through 12 wk of age (all P < 0.001, Fig. 1A) and reached a 96% increase by the end of the study period. Male db/db mice had increased body weight compared with wt mice at 8–12 wk of age (P < 0.001 at 8 and 10 wk, P < 0.05 at 12 wk), reaching a 37% increase by 10 wk after which the db/db males experienced a significant drop in body weight through to 12 wk of age (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

Metabolic phenotype of the db/db DBA/2J mouse. Body weight (A) and nonfasted blood glucose (B) in female and male db/db DBA/2J mice and wild-type (wt) controls from 6 to 12 wk of age are shown. Data are means ± SE; n = 7–12. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001: within same gender and age, groups are significantly different. C: plasma insulin in female and male db/db DBA/2J mice and wt controls at 12 wk of age. Data are means ± SE; n = 3–5. ***P < 0.001: within same gender, groups are significantly different.

Nonfasted blood glucose was similar in all groups at 6 wk of age but became significantly higher in db/db vs. wt mice from 8 through to 12 wk of age in both genders (all P < 0.001, Fig. 1B). Blood glucose did not increase significantly beyond 8 wk in female and 10 wk in male db/db mice. Plasma insulin was measured only at 12 wk of age and was significantly increased in female db/db vs. wt mice (7.15 ± 0.64 vs. 0.29 ± 0.03 ng/ml, P < 0.001, Fig. 1C), while no significant difference was observed between male groups (2.25 ± 0.98 vs. 1.36 ± 0.44 ng/ml).

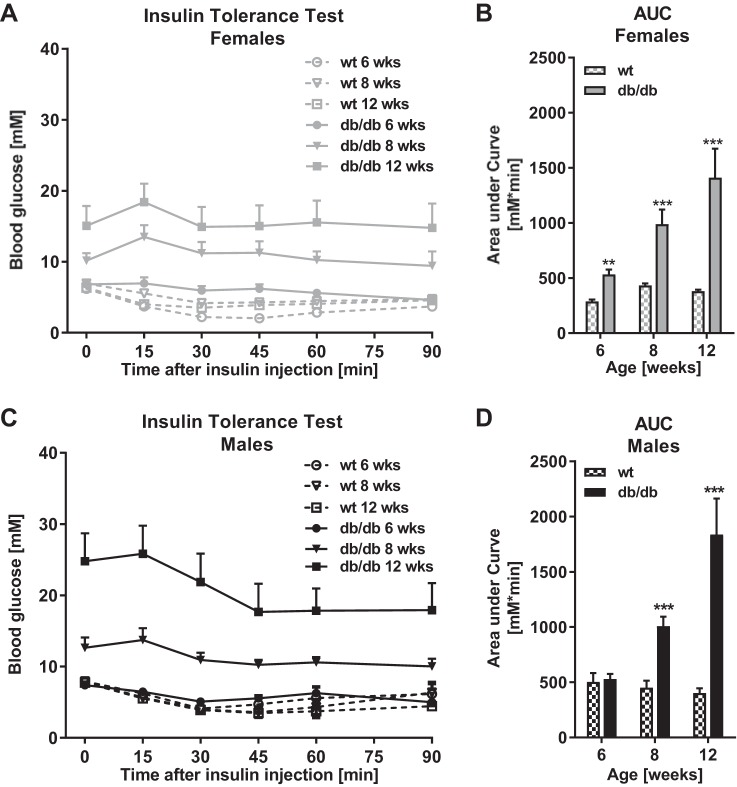

ITTs were conducted at 6, 8, and 12 wk to assess systemic insulin resistance, which was quantified by the AUC from ITT curves in females (Fig. 2A) and males (Fig. 2C). Systemic insulin resistance was significantly increased in female db/db vs. wt mice by 6 wk of age (P < 0.01, Fig. 2) and by 8 wk of age in males (P < 0.001, Fig. 2D). In both genders, insulin resistance worsened significantly from 6 through to 12 wk of age (both P < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Systemic insulin resistance in the db/db DBA/2J mouse. Systemic insulin resistance as assessed by Insulin Tolerance Tests (ITT) in female and male db/db and wt DBA/2J mice at 6, 8, and 12 wk of age is shown. A and C: mice were fasted for 6 h, and blood glucose was measured before and after intraperitoneal administration of insulin (0.20 IU/kg in females, 0.50 IU/kg in males). B and D: systemic insulin resistance quantified as area under the curve (AUC) from ITT curves in females and males, respectively. Data are means ± SE; n = 3–11. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001: at individual time points, groups are significantly different.

Albuminuria correlates with systemic insulin resistance in the db/db DBA/2J mouse.

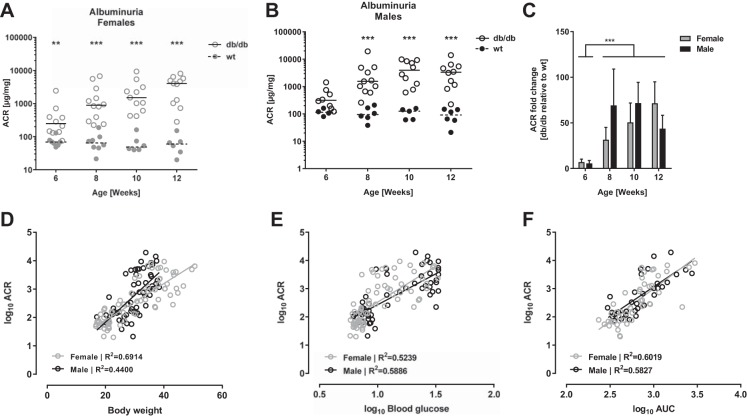

The development of albuminuria was explored in db/db DBA/2J mice from 6 to 12 wk of age and quantified by the urinary ACR. Female db/db mice had significantly higher urinary ACR compared with wt controls through 6–12 wk of age (P < 0.01 by 6 wk, P < 0.001 by 8–12 wk, Fig. 3A), while ACR was increased from 8 through to 12 wk of age in male db/db vs. wt mice (all P < 0.001, Fig. 3B). This correlates with the onset of systemic insulin resistance as presented in Fig. 2, B and D, respectively. The statistical analyses showed no significant effect of gender on the ACR fold-change between db/db and wt controls, but a significant effect of age was observed as the ACR fold-change increased from 5-fold by 6 wk to 50-fold by 12 wk of age (P < 0.001, Fig. 3C). To explore the association between albuminuria and metabolic parameters, we performed correlation analyses between urinary ACR and body weight, blood glucose, and systemic insulin resistance, respectively. We observed significant positive correlations between ACR and all three metabolic parameters in both female and male mice (all P < 0.001, see R2 in Fig. 3, D–F).

Fig. 3.

Urinary albumin excretion in the db/db DBA/2J mouse. Development of urinary albumin excretion quantified as the albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) in spot urine samples from female (A) and male (B) db/db DBA/2J mice and wt controls through 6–12 wk of age. Dots represent individual animals, and lines indicate medians; n = 4–12. **P < 0.01, ***P<0.001: at individual time points, groups are significantly different. C: ACR fold-change in db/db relative to gender- and age-matched wt controls. Bars are means ± SE; n = 4–12. ***P < 0.001: independent of gender, significant difference between time points. D–F: correlations between urinary ACR and body weight (D), nonfasted blood glucose (E), and systemic insulin resistance (F) in the db/db DBA/2J mouse. Dots represent individual animals and lines are fitted by linear regression within each gender (gray symbols, females, black symbols, males). All correlations are statistically significant (P < 0.001; R2 are given in individual graphs); n = 34–71.

Glomerular histopathology and ultrastructure in the db/db DBA/2J mouse.

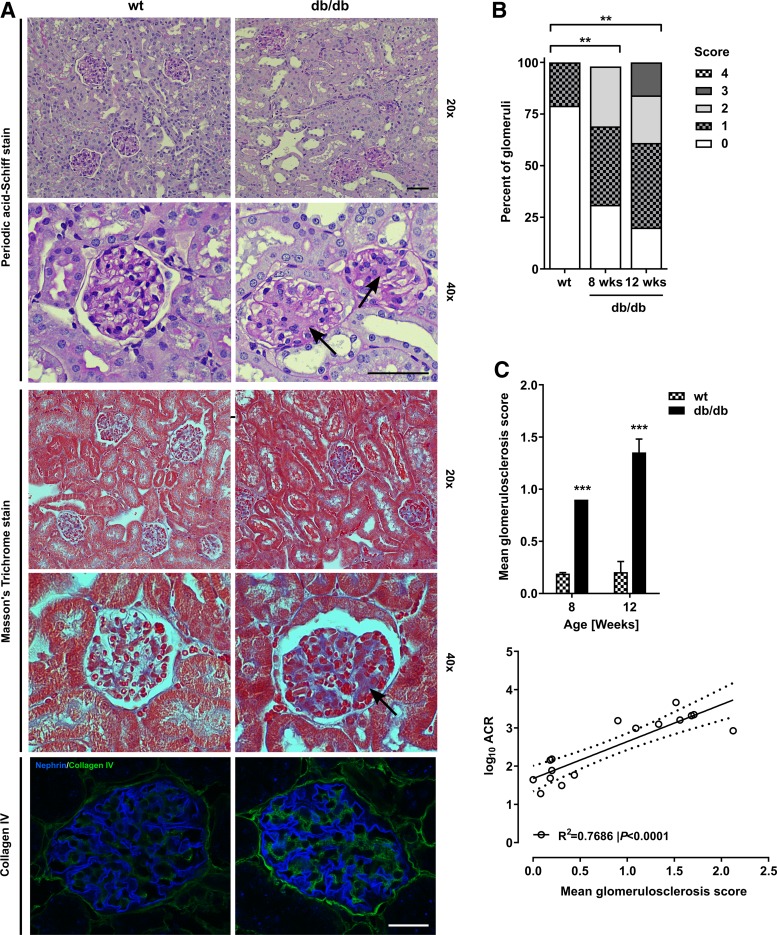

To evaluate the glomerular histopathological changes in the db/db DBA/2J mouse, kidney sections were PAS, TRI, and collagen-IV stained. Representative micrographs from 12-wk-old db/db and wt DBA/2J mice are presented in Fig. 4A. PAS-stained sections showed glomerulosclerosis in the db/db mice, but not controls, at high magnification (2nd row, arrows). Evaluation of TRI-stained sections revealed that glomerular fibrosis was present when high-magnification TRI-stained micrographs (4th row, arrows) were studied. Finally, we observed type IV collagen accumulation in db/db, but not wt glomeruli (bottom row).

Fig. 4.

Renal histopathology in the db/db DBA/2J mouse. A: representative micrographs of renal cortex and glomeruli from db/db and wt DBA/2J mice by 12 wk of age stained with periodic acid-Schiff and Masson’s trichrome as well as nephrin and collagen IV antibodies. Scale bars = 50 µm. B: distribution of glomerulosclerosis scores (GS) in db/db DBA/2J mice by 8 (n = 2) and 12 wk of age (n = 4) compared with wt DBA/2J controls (n = 6; compiled across 8–12 wk of age). C: mean GS in db/db DBA/2J and wt mice at 8 and 12 wk of age. Data are means ± SE; n = 2–4. ***P<0.001: at individual time points, groups are significantly different. D: correlation between urinary ACR and mean GS. Dots represent individual animals (n = 16); the correlation was fitted by linear regression (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.7686), and the dotted lines indicates the 95% confidence interval.

Semiquantitative analysis performed using the glomerulosclerosis score (GS) in PAS-stained kidney sections showed an increase in the percentage of glomeruli with GS ≥1 in db/db vs. wt mice by 8 wk of age (Fig. 4B). The mean GS was significantly increased in db/db vs. wt DBA/2J mice at 8 and 12 wk of age (both P < 0.001, Fig. 4C), whereas no significant worsening in GS was observed from 8 to 12 wk in db/db DBA/2J mice. The mean GS correlated positively with urinary ACR in the DBA/2J cohort (P < 0.001, R2 = 0.7686, Fig. 4D).

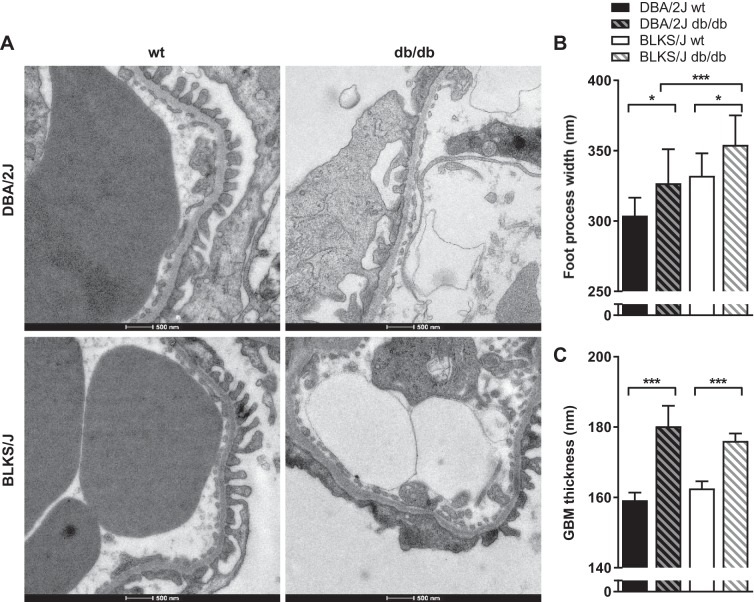

Ultrastructural changes between 12-wk-old db/db and wt controls were evaluated by TEM, and representative images are displayed in Fig. 5A (top row). Significant increases in podocyte foot process width (P < 0.05, Fig. 5B) and glomerular basement membrane (GBM) thickness (P < 0.001, Fig. 5C) were detected in db/db vs. wt DBA/2J mice.

Fig. 5.

Glomerular ultrastructure in the db/db mouse model. The ultrastructural changes in glomeruli were evaluated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at 12 wk of age. A: representative TEM micrographs of podocyte foot processes and the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) in 12-wk-old wt and db/db DBA/2J and BLKS/J mice. Glomeruli were systematically evaluated to quantify the podocyte foot process width (B) and the GBM thickness (C) in wt and db/db both within and between mouse strains. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001: groups are significantly different.

Effects of genetic background on the metabolic phenotype in the db/db mouse model.

The metabolic phenotype of male db/db DBA/2J and BLKS/J mice was compared to explore the effects of genetic background on the phenotypical manifestation of the db allele. The body weight of db/db DBA/2J mice was 16-20% lower than that of db/db BLKS/J mice throughout the study period (P < 0.001, Table 2). Unlike db/db DBA/2J mice, db/db BLKS/J males did not demonstrate any weight loss during the study period, although their body weight was unchanged from 10 wk of age. Nonfasted blood glucose was significantly lower in db/db DBA/2J mice at 8 wk (P < 0.001, Table 2), but reached similar levels to that of db/db BLKS/J mice by 12 wk of age. Systemic insulin resistance was significantly lower in db/db DBA/2J vs. BLKS/J males at 8 and 12 wk of age (P < 0.001 and P < 0.05, respectively, Table 2). In wt mice, genetic background did not significantly affect the metabolic parameters presented in Table 2. Finally, comparisons of plasma insulin levels showed no significant differences between male DBA/2J and BLKS/J cohorts in either db/db (2.25 ± 0.98 vs. 4.64 ± 2.45 ng/ml) or wt mice (1.36 ± 0.44 vs 1.11 ± 0.2 ng/ml).

Table 2.

Metabolic parameters in DBA/2J and BLKS/J db/db mouse models

| Body Weight, g |

Nonfasted Blood Glucose, mM |

Area Under Curve, mM * min |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt | db/db | Wt | db/db | wt | db/db | |

| 8 wk | ||||||

| DBA/2J | 24.0 ± 1.5 | 33.1 ± 0.7*‡ | 7.88 ± 0.39 | 16.94 ± 2.09*‡ | 450.9 ± 64.2 | 1,007.3 ± 87.4*‡ |

| BLKS/J | 25.7 ± 0.5 | 39.7 ± 0.8* | 6.95 ± 0.29 | 26.05 ± 1.52* | 372.4 ± 20.2 | 2,264.8 ± 147.5* |

| 10 wk | ||||||

| DBA/2J | 25.5 ± 1.6 | 34.9 ± 0.7*‡ | 7.75 ± 0.45 | 27.31 ± 1.19* | ND | ND |

| BLKS/J | 27.8 ± 0.8 | 42.2 ± 0.9* | 7.30 ± 0.32 | 29.9 ± 1.21* | ND | ND |

| 12 wk | ||||||

| DBA/2J | 27.3 ± 1.5 | 33.0 ± 1.1*‡ | 7.77 ± 0.32 | 31.01 ± 0.86* | 402.3 ± 42.8 | 1,836.8 ± 326.1*† |

| BLKS/J | 28.7 ± 0.8 | 42.1 ± 1.2* | 7.10 ± 0.21 | 28.63 ± 1.21* | 405.9 ± 15.3 | 2,530.5 ± 121.0* |

Data are means ± SE; n = 3–12 for DBA/2J mice, n = 6 for BLKS/J mice. ND, not determined.

P < 0.001: within same strain and age, groups are significantly different.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.001: within same group and age, strains are significantly different.

Effects of genetic background on kidney injury in the db/db mouse model.

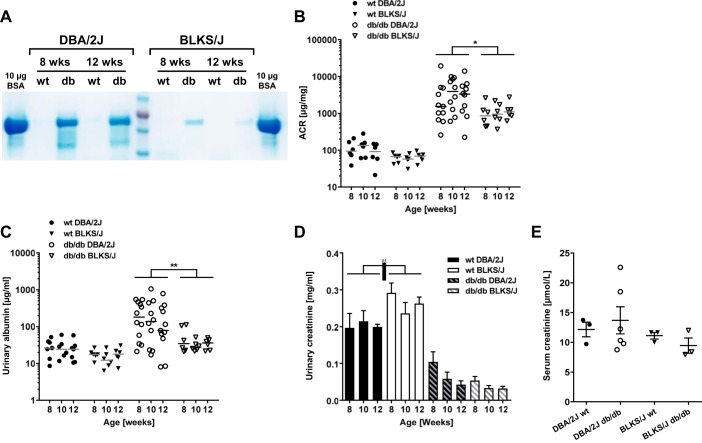

To evaluate the effects of genetic background on the susceptibility to kidney injury, we compared albuminuria as well as renal structural and histopathological changes between male db/db DBA/2J and db/db BLKS/J mice. Qualitative analysis of urine samples by SDS-PAGE indicated increased urinary albumin concentrations in db/db DBA/2J vs. db/db BLKS/J mice at 8 and 12 wk of age (Fig. 6A). In addition, urinary ACR was significantly higher in db/db DBA/2J vs. db/db BLKS/J mice (P < 0.05, Fig. 6B), with ACR-fold changes in db/db vs. wt mice within the male DBA/2J cohort ranging from 32- to 44-fold compared with 16- to 18-fold in the BLKS/J2 cohort. Urinary concentrations of albumin were also significantly higher in DBA/2J vs. BLKS/J db/db males (P < 0.01, Fig. 6C). Furthermore, the urinary creatinine concentrations were similar in db/db mice between strains, but significantly higher in BLKS/J vs. DBA/2J wt mice (P < 0.05, Fig. 6D). Finally, we assessed serum creatinine levels in a subset of DBA2J and BLKS/J mice at 12 wk of age. This revealed no significant differences between db/db and their wt controls on either the DBA2J or BLKS/J backgrounds (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

Modulation of urinary albumin excretion by genetic background in the db/db mouse model. Urinary albumin excretion was evaluated in spot urine samples from male db/db and wt DBA/2J and BLKS/J mice through 8–12 wk of age. A: evaluation by SDS-PAGE (5 µl urine/lane) followed by Coomassie stain using BSA (~66 kDa) as a positive control. B and C: urinary ACR (B) and albumin concentrations (C) in spot urine samples. Dots represent individual animals (n = 4–12), and horizontal lines indicate medians. D: urinary creatinine concentrations in spot urine samples. Data are means ± SE; n = 4–12. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01: within same group, strains are significantly different. E: dot blot of serum creatinine measured in 12-wk-old mice. Analysis with a 1-way ANOVA revealed no significant difference between any groups; n = 3–6/group.

The impact of genetic background on kidney weights and glomerular histological changes was also investigated. First, relative kidney weight was significantly reduced in db/db vs. wt BLKS/J mice (P < 0.001, Table 3), while no significant differences in kidney weight were observed between DBA/2J groups. Between strains, relative, but not absolute kidney weight was significantly higher in db/db DBA/2J vs. BLKS/J mice (P < 0.01, Table 3).

Table 3.

Kidney weights and glomerular structure in DBA/2J and BLKS/J db/db mouse models

| Absolute Weight, g |

Relative Weight, mg kidney weight/g body weight |

Mean Glomerulosclerosis Score |

Glomerular Area, µm2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| wt | db/db | wt | db/db | wt | db/db | wt | db/db | |

| DBA/2J | 0.489 ± 0.034† | 0.524 ± 0.068 | 18.42 ± 0.71‡ | 16.79 ± 3.17‡ | 0.21 ± 0.10 | 1.35 ± 0.13* | 3,878 ± 86 | 4,653 ± 238* |

| LKS/J | 0.379 ± 0.016 | 0.410 ± 0.024 | 13.77 ± 0.51 | 9.78 ± 0.63* | 0.45 ± 0.13 | 1.47 ± 0.10* | 4,274 ± 197 | 4,765 ± 220 |

Data are means ± SE; n = 4–6.

P < 0.001: within same strain, significant difference between groups.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01: within same group, strains are significantly different.

Semiquantitative histological evaluation showed increased GS in db/db vs. wt mice by 12 wk of age in both strains (both P < 0.001, Table 3), whereas the glomerular area was significantly enlarged in db/db vs. wt in the DBA/2J strain (P < 0.001, Table 3), but not BLKS/J. Finally, comparison of the DBA/2J and BLKS/J cohorts showed no significant effect of genetic background on GS and glomerular area in db/db and in wt mice.

The effect of background strain on ultrastructural changes in glomeruli was evaluated by TEM, and representative micrographs are presented in Fig. 5A. In both strains, podocyte foot process width and GBM thickness were significantly increased in db/db vs. wt mice (for both strains P < 0.05, Fig. 5B and P < 0.001, Fig. 5C, respectively). Furthermore, the width of foot processes was significantly higher in db/db BLKS/J vs. DBA/2J mice (P < 0.001, Fig.5B), while the GBM thickness did not differ between strains (Fig. 5C). No significant differences were observed between DBA/2J and BLKS/J wt mice.

DISCUSSION

DN research and drug development is challenged by the shortcomings of current animal models. Considerable resources are therefore invested in the development of novel animal models that reproduce features of human disease. In this study, we followed the advancement of early DN in the db/db DBA/2J mouse and found that it developed robust albuminuria starting between 6 and 8 wk of age that correlated closely with systemic insulin resistance, body weight, and blood glucose levels. We then compared male db/db DBA/2J mice with an age-matched cohort of male db/db BLKS/J mice, which is the major strain used in type 2 DN research, and found a significant effect of genetic background on the severity of urinary albumin excretion despite similar levels of hyperglycemia and systemic insulin resistance in both strains. This study underlines the impact of genetic background on the propensity to renal injury in mouse models of diabetes and DN, and confirms the susceptibility of the DBA/2J strain to albuminuric kidney disease.

Like BLKS/J, the DBA/2J strain is susceptible to the diabetogenic actions of the db allele. This causes these mouse strains to develop overt type 2 diabetes with pancreatic exhaustion, β-cell depletion, and insulinopenia after a preceding period of systemic insulin resistance, leading to pancreatic hypertrophy and hyperinsulinemia as in human type 2 diabetes patients. The duration of the gradual transition from systemic insulin resistance to overt type 2 diabetes depends on and varies between mouse strains and gender (20). Here, we observed an early onset of hyperglycemia and systemic insulin resistance in female and male db/db DBA/2J mice at 6 and 8 wk of age, respectively. As seen in various mouse models of diabetes (10, 20), males displayed accelerated advancement of the diabetic phenotype relative to females and developed severe hyperglycemia and insulinopenia, resulting in weight loss starting at 10 wk of age possibly due to glycosuria. In contrast, female db/db DBA/2J mice displayed sustained hyperinsulinemia by 12 wk of age, explaining the stabilized, although elevated, blood glucose levels through 8–12 wk of age. Furthermore, the metabolic manifestations of the db allele, in terms of hyperglycemia and systemic insulin resistance, were similar in the male db/db DBA/2J and BLKS/J cohorts by 12 wk of age. These data are consistent with previous studies by Leiter et al. (20), who studied the metabolic parameters in DBA/2J and BLKS/J db/db mice and classified them “diabetes prone” in contrast to “diabetes-resistant” C57BL/6 mice.

In human patients as well as in animal models, albuminuria is used as the hallmark biomarker of DN. In mice, it has been shown that genetic factors modulate the levels of albuminuria in models of type 1 diabetes, including the STZ-induced and Akita models (14, 29, 34) as well as in type 2 diabetes in the db/db model (31). In this study, we observed robust albuminuria by 8 wk of age in both female and male db/db DBA/2J mice. Furthermore, we saw a development in albuminuria with ACR fold-changes in db/db mice relative to age- and gender-matched controls resulting in a 56-fold increase in females and a 44-fold increase in males by 12 wk of age. As far as we are aware, this is the first study that has examined the development of albuminuria in the db/db model on a DBA2J background. We decided to compare this genetic strain to the most widely studied strain that develops early DN, BLKS/J. Importantly, we studied both strains of mice in the same environment, using the same feeding regimen, and collected all samples in a similar manner. Despite these measures, the different vendors of the mouse strains cannot be excluded as a confounding factor. Our head-to-head strain comparison showed significantly higher levels of urinary albumin excretion in male db/db DBA/2J mice compared with db/db BLKS/J mice as assessed by urinary ACR. This feature was mainly driven by an increase in crude urinary albumin excretion rather than a reduction in urinary creatinine levels. Furthermore, although we didn’t measure formal glomerular filtration rates (GFRs) in our mice, we did measure serum creatinine levels in a subset of mice, which were not significantly different. This suggests that there was not a major difference in the level of hyperfiltration between DBA2J and BLKS mice. GFRs have not been previously assessed in db/db DBA2J mice; however, they have been performed in BLKS db/db and wt mice. These studies have revealed either no difference in the level of GFR between these groups at 24 wk (35) or a small increase in the db/db mice at 18 wk (4). In the future, it will be interesting to rigorously assess the progression of hyperfiltration in the db/db DBA2J model using formal GFR assessment, but this was not the focus of this study.

Alongside albuminuria, features of DN in the db/db mouse include histopathological findings such as glomerulosclerosis and glomerular enlargement as well as ultrastructural changes including foot process effacement and GBM thickening. Our data showed that glomerulosclerosis was increased in db/db compared with wt DBA/2J mice by 8 wk of age, and glomerular enlargement was detectable by 12 wk of age. Compared with the db/db BLKS/J cohort, we detected no differences in these features in the db/db DBA2J males. It has previously been described in mouse models of DN that increased levels of urinary albumin excretion do not translate into exacerbation of histopathological changes (14, 28). This may simply be due to the superior sensitivity of the urinary albumin excretion relative to semiquantitative histological analysis in detecting renal damage. Furthermore, the ultrastructural changes of the glomeruli described here do not explain the observed increase in ACR in db/db DBA/2J mice compared with the BLKS/J strain. Together, our data suggest that the increased susceptibility to albuminuria of the DBA/2J mouse may be caused by underlying genetic makeup, leading to differences in the molecular susceptibility to albuminuric kidney disease.

We characterized the development of metabolic parameters during the transition from systemic insulin sensitivity to resistance, and through to overt diabetes. We observed positive correlations between ACR and systemic insulin resistance as well as glomerulosclerosis scores in the db/db DBA/2J mouse model. Clinically, these findings are potentially important as they mimic the association between microalbuminuria and insulin resistance observed in nondiabetic metabolic syndrome patients (24, 27) and in diabetic subjects (9, 15). Thus our findings support the applicability of the db/db DBA/2J mouse to study these early stages of insulin-resistant glomerulopathies and DN to decipher the pathophysiological events that may precede and accelerate the progression to late-stage DN.

Together with a growing amount of experimental data from mouse models of diabetes (13, 14) and models of diet-induced obesity (32), the present study confirms the notion that DBA/2J mice display enhanced sensitivity to metabolically induced albuminuria kidney disease. Compared with BLKS/J mice, at its onset, systemic insulin resistance was less in the db/db DBA/2J mice, but they exhibited significantly more albuminuria. This suggests that the inherent cellular insulin resistance in DBA/2J mice must be greater than that in the BLKS/J strain, which has previously been described by others (3). Studies have been conducted to identify genetic contributors to diabetes susceptibility in the db/db mouse model (8), but fail to distinguish diabetes and DN susceptibility loci. Further genetic analyses are therefore required to identify genes that are differentially expressed between the diabetes-prone DBA/2J and BLKS/J strains and that may explain the molecular difference underlying the present observations as previously achieved in a comparison between the DBA/2J and C57BL/6 strains (29). Finally, as the DBA/2J is a pure inbred strain, it is attractive as it will be possible to generate db/db mice carrying specific transgenes that can be back-crossed onto this albuminuric-susceptible genetic background to decipher the molecular mechanisms of this underlying insulin resistance and the influence on the establishment and development of DN in the kidney, glomerulus, and even in individual cell populations such as the podocytes in this kidney disease-prone strain.

In summary, we have demonstrated that the db/db DBA/2J mouse develops robust albuminuria by 8 wk of age alongside histopathological features of early DN including glomerulosclerosis and glomerular enlargement by 8 and 12 wk of age, respectively. This is closely linked to systemic insulin resistance. The observed correlations between albuminuria and metabolic parameters support the applicability of this model as a clinically relevant model for biomedical research and drug development in insulin-resistant states, diabetes, and early DN. Further studies are required to explore whether the DBA/2J background also display an enhanced acceleration of the progression to late-stage DN in the db/db mouse model of diabetes.

GRANTS

This work was supported by an MRC Senior Clinical Fellowship to R. J. M. Coward (MR/K010492/1).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

M.V.x., V.P., K.S., and R.J.M.C. performed experiments; M.V.x., V.P., and K.S. analyzed data; M.V.x., J.W., L.N.F., and R.J.M.C. interpreted results of experiments; M.V.x. prepared figures; M.V.x., J.W., L.N.F., and R.J.M.C. drafted manuscript; M.V.x., V.P., J.W., L.N.F., and R.J.M.C. edited and revised manuscript; M.V.x. and R.J.M.C. approved final version of manuscript.

DISCLOSURES

This study was supported financially by Novo Nordisk. M. V. Østergaard, J. Worm, and L. N. Fink are all current or former employees at Novo Nordisk.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Stephan D. Bouman from Global Research, Novo Nordisk, for counseling on in vivo animal procedures. We also thank Fern Barrington and Chris Neal from Bristol Renal, University of Bristol, for skillful support with animal breeding and genotyping, and ultrastructural analyses, respectively. Finally, we thank the staff of the Histology Services Unit and the Wolfson Bioimaging Facility, University of Bristol, for technical support during this project.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alpers CE, Hudkins KL. Mouse models of diabetic nephropathy. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 20: 278–284, 2011. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283451901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arakawa K, Ishihara T, Oku A, Nawano M, Ueta K, Kitamura K, Matsumoto M, Saito A. Improved diabetic syndrome in C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice by oral administration of the Na+-glucose cotransporter inhibitor T-1095. Br J Pharmacol 132: 578–586, 2001. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berglund ED, Li CY, Poffenberger G, Ayala JE, Fueger PT, Willis SE, Jewell MM, Powers AC, Wasserman DH. Glucose metabolism in vivo in four commonly used inbred mouse strains. Diabetes 57: 1790–1799, 2008. doi: 10.2337/db07-1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bivona BJ, Park S, Harrison-Bernard LM. Glomerular filtration rate determinations in conscious type II diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F618–F625, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00421.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brosius FC III, Alpers CE, Bottinger EP, Breyer MD, Coffman TM, Gurley SB, Harris RC, Kakoki M, Kretzler M, Leiter EH, Levi M, McIndoe RA, Sharma K, Smithies O, Susztak K, Takahashi N, Takahashi T; Animal Models of Diabetic Complications Consortium. Mouse models of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 2503–2512, 2009. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009070721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen MP, Lautenslager GT, Shearman CW. Increased urinary type IV collagen marks the development of glomerular pathology in diabetic d/db mice. Metabolism 50: 1435–1440, 2001. doi: 10.1053/meta.2001.28074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman DL. Obese and diabetes: two mutant genes causing diabetes-obesity syndromes in mice. Diabetologia 14: 141–148, 1978. doi: 10.1007/BF00429772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis RC, Schadt EE, Cervino ACL, Péterfy M, Lusis AJ. Ultrafine mapping of SNPs from mouse strains C57BL/6J, DBA/2J, and C57BLKS/J for loci contributing to diabetes and atherosclerosis susceptibility. Diabetes 54: 1191–1199, 2005. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Cosmo S, Minenna A, Ludovico O, Mastroianno S, Di Giorgio A, Pirro L, Trischitta V. Increased urinary albumin excretion, insulin resistance, and related cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes: evidence of a sex-specific association. Diabetes Care 28: 910–915, 2005. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.4.910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Franconi F, Seghieri G, Canu S, Straface E, Campesi I, Malorni W. Are the available experimental models of type 2 diabetes appropriate for a gender perspective? Pharmacol Res 57: 6–18, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman BI, Bostrom M, Daeihagh P, Bowden DW. Genetic factors in diabetic nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 1306–1316, 2007. doi: 10.2215/CJN.02560607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groop L, Ekstrand A, Forsblom C, Widén E, Groop PH, Teppo AM, Eriksson J. Insulin resistance, hypertension and microalbuminuria in patients with type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 36: 642–647, 1993. doi: 10.1007/BF00404074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gurley SB, Clare SE, Snow KP, Hu A, Meyer TW, Coffman TM. Impact of genetic background on nephropathy in diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F214–F222, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00204.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurley SB, Mach CL, Stegbauer J, Yang J, Snow KP, Hu A, Meyer TW, Coffman TM. Influence of genetic background on albuminuria and kidney injury in Ins2(+/C96Y) (Akita) mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F788–F795, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90515.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu CC, Chang HY, Huang MC, Hwang SJ, Yang YC, Tai TY, Yang HJ, Chang CT, Chang CJ, Li YS, Shin SJ, Kuo KN. Association between insulin resistance and development of microalbuminuria in type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 34: 982–987, 2011. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu FB, Li TY, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Manson JE. Television watching and other sedentary behaviors in relation to risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. JAMA 289: 1785–1791, 2003. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.14.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hummel KP, Dickie MM, Coleman DL. Diabetes, a New Mutation in Mouse. Science 153: 1127-1128, 1966. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3740.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keppler A, Gretz N, Schmidt R, Kloetzer HM, Groene HJ, Lelongt B, Meyer M, Sadick M, Pill J. Plasma creatinine determination in mice and rats: an enzymatic method compares favorably with a high-performance liquid chromatography assay. Kidney Int 71: 74–78, 2007. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leiter EH. The influence of genetic background on the expression of mutations at the diabetes locus in the mouse IV. Male lethal syndrome in CBA/Lt mice. Diabetes 30: 1035–1044, 1981. doi: 10.2337/diab.30.12.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leiter EH, Coleman DL, Hummel KP. The influence of genetic background on the expression of mutations at the diabetes locus in the mouse. III. Effect of H-2 haplotype and sex. Diabetes 30: 1029–1034, 1981. doi: 10.2337/diab.30.12.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim AK, Ma FY, Nikolic-Paterson DJ, Thomas MC, Hurst LA, Tesch GH. Antibody blockade of c-fms suppresses the progression of inflammation and injury in early diabetic nephropathy in obese db/db mice. Diabetologia 52: 1669–1679, 2009. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1399-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mao HZ, Roussos ET, Péterfy M. Genetic analysis of the diabetes-prone C57BLKS/J mouse strain reveals genetic contribution from multiple strains. Biochim Biophys Acta 1762: 440–446, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mishra R, Emancipator SN, Miller C, Kern T, Simonson MS. Adipose differentiation-related protein and regulators of lipid homeostasis identified by gene expression profiling in the murine db/db diabetic kidney. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F913–F921, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00323.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mykkänen L, Zaccaro DJ, Wagenknecht LE, Robbins DC, Gabriel M, Haffner SM. Microalbuminuria is associated with insulin resistance in nondiabetic subjects: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Diabetes 47: 793–800, 1998. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.5.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orchard TJ, Chang YF, Ferrell RE, Petro N, Ellis DE. Nephropathy in type 1 diabetes: a manifestation of insulin resistance and multiple genetic susceptibilities? Further evidence from the Pittsburgh Epidemiology of Diabetes Complication Study. Kidney Int 62: 963–970, 2002. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palmer ND, Freedman BI. Insights into the genetic architecture of diabetic nephropathy. Curr Diab Rep 12: 423–431, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0279-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pilz S, Rutters F, Nijpels G, Stehouwer CDA, Højlund K, Nolan JJ, Balkau B, Dekker JM, RISC Investigators . Insulin sensitivity and albuminuria: the RISC study. Diabetes Care 37: 1597–1603, 2014. doi: 10.2337/dc13-2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qi Z, Fujita H, Jin J, Davis LS, Wang Y, Fogo AB, Breyer MD. Characterization of susceptibility of inbred mouse strains to diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 54: 2628–2637, 2005. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheehan S, Tsaih SW, King BL, Stanton C, Churchill GA, Paigen B, DiPetrillo K. Genetic analysis of albuminuria in a cross between C57BL/6J and DBA/2J mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F1649–F1656, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00233.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Susztak K, Raff AC, Schiffer M, Böttinger EP. Glucose-induced reactive oxygen species cause apoptosis of podocytes and podocyte depletion at the onset of diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes 55: 225–233, 2006. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.01.06.db05-0894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tesch GH, Lim AKH. Recent insights into diabetic renal injury from the db/db mouse model of type 2 diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 300: F301–F310, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00607.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wicks SE, Nguyen T-T, Breaux C, Kruger C, Stadler K. Diet-induced obesity and kidney disease - In search of a susceptible mouse model. Biochimie 124: 65–73, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wild S, Roglic G, Green A, Sicree R, King H. Global prevalence of diabetes: estimates for the year 2000 and projections for 2030. Diabetes Care 27: 1047–1053, 2004. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.5.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu X, Davis RC, McMillen TS, Schaeffer V, Zhou Z, Qi H, Mazandarani PN, Alialy R, Hudkins KL, Lusis AJ, LeBoeuf RC. Genetic modulation of diabetic nephropathy among mouse strains with Ins2 Akita mutation. Physiol Rep 2: e12208, 2014. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao HJ, Wang S, Cheng H, Zhang MZ, Takahashi T, Fogo AB, Breyer MD, Harris RC. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase deficiency produces accelerated nephropathy in diabetic mice. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2664–2669, 2006. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006070798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]