Abstract

l-Arginine (L-Arg) is the substrate for nitric oxide synthase (NOS) to produce nitric oxide (NO), a signaling molecule that is key in cardiovascular physiology and pathology. In cardiac myocytes, L-Arg is incorporated from the circulation through the functioning of system-y+ cationic amino acid transporters. Depletion of L-Arg leads to NOS uncoupling, with O2 rather than L-Arg as the terminal electron acceptor, resulting in superoxide formation. The reactive oxygen species (ROS) superoxide (O2˙−), combined with NO, may lead to the production of the reactive nitrogen species (RNS) peroxynitrite (ONOO–), which is recognized as a major contributor to myocardial depression. In this study we aimed to determine the levels of external L-Arg that trigger ROS/RNS production in cardiac myocytes. To this goal, we used a two-step experimental design in which acutely isolated cardiomyocytes were loaded with the dye coelenterazine that greatly increases its fluorescence quantum yield in the presence of ONOO– and O2˙−. Cells were then exposed to different concentrations of extracellular L-Arg and changes in fluorescence were followed spectrofluorometrically. It was found that below a threshold value of ~100 µM, decreasing concentrations of L-Arg progressively increased ONOO–/ O2˙−-induced fluorescence, an effect that was not mimicked by d-arginine or l-lysine and was fully blocked by the NOS inhibitor l-NAME. These results can be explained by NOS aberrant enzymatic activity and provide an estimate for the levels of circulating L-Arg below which ROS/RNS-mediated harmful effects arise in cardiac muscle.

Keywords: cationic amino acid transporters, nitric oxide, superoxide, peroxynitrite

l-arginine (L-Arg) is a multifunctional semiessential amino acid that is synthesized in the small intestine and kidneys and that becomes essential during the physiologic growth of infants or in individuals experiencing catabolic states such as cancer, trauma, stress, sepsis, starvation, and severe burns or with intestine or kidney dysfunction (1). During these metabolic states, L-Arg should be incorporated from exogenous sources to ensure proper extra- and intracellular levels for this amino acid. Arginine is metabolized through multiple pathways (37) and thus its homeostasis and steady-state plasma levels are the result of fine-tuned interactions among endogenous production, dietary protein supply, body protein turnover and the metabolic state of the organism. In addition, some conditions increase L-Arg catabolism (for example, augmented plasma arginase activity; Ref. 37 and references therein) resulting in low circulating levels of this amino acid, a situation that may lead to or worsen disease. Surprisingly, the threshold L-Arg concentration below which pathologic processes are triggered has not been determined.

Among its many roles, L-Arg is the substrate for the enzymatic production of nitric oxide (NO), a signaling molecule that plays a central role in cardiovascular pathophysiology. In heart, NO has negative chronotropic, negative or positive inotropic, and positive lusitropic effects (31), and alterations of the L-Arg-NO pathway have been reported in chronic heart failure (33). NO synthesis requires the presence of L-Arg inside the cells of responsive tissues. While some cell types can synthesize L-Arg from ornithine or citrulline (20, 50), L-Arg is not produced within cardiac myocytes and thus cardiac muscle must import this amino acid from the circulation. Therefore, the carriers responsible for L-Arg transport are expected to play a key role in the metabolism of this amino acid and NO in heart. We have previously solved the kinetic features of the cationic amino acid transporters (CATs) found in cardiac myocytes (28, 40). Using cardiac sarcolemmal vesicles, we discovered high- and low-affinity L-Arg uptake components that function simultaneously. Although with a Km in the millimolar range, the low-affinity CAT, because of its high capacity, was found to be physiologically relevant as it is responsible for ~50% of total L-Arg transport at normal plasma levels of this amino acid (28).

NO biosynthesis is mediated by the enzyme nitric oxide synthase (NOS; EC 1.14.13.39), a dioxygenase composed by reductase and oxidase domains that uses NADPH and O2 in the oxidation of a guanidino nitrogen from L-Arg to produce NO and l-citrulline (19). This reaction requires flavin mononucleotide, FAD, tetrahydrobiopterin, and, in the constitutively expressed endothelial (eNOS) and neuronal (nNOS) isoforms of the enzyme, a Ca-CaM complex (9, 38). The Ca-CaM complex binds between the oxygenase and reductase domains, after which electrons flow from reduced NADPH through the reduced flavins into the oxidase domain. At the heme site, O2 is reduced and incorporated into L-Arg to yield the reaction products. Km values of 1.5–3 μM have been reported for L-Arg activation of constitutive NOS isoforms from assays in vitro (Ref. 16 and references therein). Nonetheless, studies by us and others found a low-affinity L-Arg stimulation of NO production at concentrations as much as three orders of magnitude larger than the Km for this substrate, an effect known as “the arginine paradox” (6, 11, 55).

Depletion of L-Arg (and/or tetrahydrobiopterin) leads to NOS uncoupling, i.e., uncoupling of NADPH oxidation and NO synthesis, with O2 rather than L-Arg as the terminal electron acceptor, resulting in the formation of superoxide (O2˙−) by all three NOS isoforms (Ref. 52 and references therein). Combination of O2˙− with NO from enzymatic or nonenzymatic sources will result in the production of peroxynitrite (ONOO–) (5), an oxidizing agent associated with cell damage, decreased myocardial contractility, and congestive heart failure (15). For example, ONOO– infusion into isolated working rat hearts impairs cardiac contractile function by reducing cardiac efficiency, and endogenous formation of ONOO– contributes to myocardial stunning in ischemia/reperfusion injury as well as spontaneous loss of cardiac function (reviewed in Ref. 15).

Peroxynitrite production when NOS is exposed to low L-Arg concentrations has been detected in a kidney cell line (51) and macrophages (53). At the molecular level, ONOO– is responsible for oxidative protein modifications (2, 23), in particular the reversible nitration of Tyr residues in target proteins (12, 14, 45). Myofibrillar creatine kinase (34), the cytoskeletal protein α-actinin (8), the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (26), and aconitase (10) are particularly sensitive targets for ONOO–-induced nitration in human myocardium.

Clearly, an adequate cellular supply of L-Arg is needed to direct NOS activity towards NO production thus preventing the generation of harmful by-products. In this work, we assessed ex vivo the range of extracellular L-Arg levels required for proper NOS function and below which ONOO– production and oxidative damage arise within cardiomyocytes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats weighing between 200 and 300 g were injected with pentobarbital sodium (Nembutal; 100 mg/kg ip), and hearts were removed under complete anesthesia. Animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the New Jersey Medical School. Fresh cardiac ventricular myocytes were enzymatically isolated at the beginning of each experimental day as previously described (35, 40) and suspended in Langendorff solution (see below) at a density of ~5,000 cells/ml.

Peroxynitrite reactivity and concentration.

Tetramethylammonium peroxynitrite (TMA-OONO−; Fig. 1) was aliquoted and stored at −80°C. Peroxynitrite is stable in alkaline solutions; therefore, the stock TMA-OONO− was supplied at a nominal concentration of 15.5 mM in 10 mM KOH. For determination of the exact concentration on the day of the experiment, an aliquot of stock OONO− was thawed and properly diluted in KOH, and the absorbance was measured at a wavelength of 302 nm. The stock OONO− concentration was then calculated using its molar extinction coefficient (1,670 cm−1 M−1) and the dilution factor. The calculated TMA-OONO− stock concentration varied between 12 and 15 mM. Solutions with OONO− concentrations below 12 mM were not used in the experiments. Decomposed TMA-OONO− was obtained by incubating this reagent at pH 7.2 (Langendorff solution, see below) for 60 min at room temperature.

Fig. 1.

Coelenterazine and tetramethylammonium peroxynitrite chemical structure representations.

Fluorescence experiments.

Freshly isolated myocytes were suspended in 1.5 ml of Langendorff solution containing the following (in mM): 135 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 0.2 CaCl2, 0.33 NaH2PO4, and 10 HEPES-Na pH 7.2 at 23°C, and incubated for 30 min at 23°C with 20 µM of the dye coelenterazine (Fig. 1) in aluminum foil-wrapped glass tubes with occasional mixing. Cells were washed twice to remove the excess coelenterazine and resuspended in 2 ml of Langendorff solution, and 200-µl aliquots were distributed in 96-well plates. After background fluorescence was recorded, desired concentrations of TMA-OONO−/KOH (15 µl) and L-Arg (25 µl) were added and the time course of fluorescence changes followed with a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer using a λex = 400 nm and a λem = 514 nm. The total time elapsed from cardiomyocyte isolation to fluorescence measurements was 60–90 min and cells were kept at room temperature.

Immunocytochemistry assays.

Isolated cardiac myocytes were plated on six-well plates (~1000 cells/sample) and incubated for 1 h at 37°C on laminin-coated (10 μg/ml) coverslips. Attached cells were treated for 30 min with L-Arg (various concentrations), S-nitroso-N-acetyl-dl-penicillamine (SNAP) + pyrogallol, L-Arg + N-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME), L-Arg + nitrotyrosine, or Langendorff’s buffer. Myocytes were then fixed by treatment with 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature. After being rinsed, plates were incubated with protein G purified mouse monoclonal anti-nitrotyrosine IgG (1:500 dilution; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) and Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:250 dilution; Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Nuclei were identified with ProLong gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Confocal images of 3-nitrotyrosine and DAPI distribution (×40 magnification) were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope. Intensity analysis was performed by NIS element measurements (after subtracting DAPI staining) and normalized to myocyte area, as estimated from the number of pixels in the object.

Western blotting.

Rat cardiac myocytes, mouse hepatocytes, HUVEC P7 cells, and mouse whole brain tissue were washed three times with cold PBS and homogenized with the following lysis buffer: RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 10 μg/μl leupeptin, 5 μg/μl aprotinin, and 250 μM PMSF. The supernatant was conserved after spinning down this homogenate at 15,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Protein concentration was determined using the BCA assay. For electrophoresis assays, 8% Bis-Tris SDS gels were loaded with 15 μg of control samples or 150 μg of cardiac myocyte or hepatocyte lysates. Gels were run at 140 V until the molecular weight markers were fully separated and band materials were transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS-T for 1 h, washed for 10 min using TBS-T and incubated with the primary antibody (anti-mouse eNOS/nNOS at a 1:2500 dilution, from BD Transduction Laboratory, San Jose, CA) in 5% milk in TBS-T, overnight at 4°C with gentle shaking. Membranes were then washed three times with TBS-T (10 min/each) and the secondary antibody was applied (mouse IgG at a 1:2,500 dilution, from Pierce, Rockford, IL) with gentle shaking for 1 h, after which the washing steps were repeated. Enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Pierce, Rockford, IL) was used to visualize the bands.

Statistics.

Data are presented as means ± SE for the indicated number of experiments. Statistical significance was assessed using Student’s t-test (P < 0.05). Curve fitting was performed with nonlinear least-squares routines included in SigmaPlot (version 10.0, Systat Software, Richmond, CA) using statistical weights proportional to (SE)−1 or (SE)−2.

Reagents.

Tetramethylammonium peroxynitrite was purchased from Axxora (San Diego, CA). Coelenterazine was purchased from Sigma in batches of 50 μg/50 μl 70% ethanol, aliquoted and stored at −80°C. SNAP was from Calbiochem (Billerica, MA; stored at −20°C protected from light), and pyrogallol was purchased from Sigma (stored at room temperature, protected from light). The hydrochloride salts of l-lysine (L-Lys), d-arginine (D-Arg), and L-Arg were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. l-NAME and uric acid were from Sigma and 7-nitro indazole sodium (7-NINA) was from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA). Nitrotyrosine was purchased from EMD Millipore. Collagenase type II was obtained from Worthington Biochemical (Lakewood, NJ). Salts and reagents were of analytical reagent grade.

RESULTS

Experiments were designed to determine how low must extracellular L-Arg levels fall to trigger NOS-mediated superoxide/peroxynitrite production in cardiac myocytes. Toward this goal, we used coelenterazine, which has been described to produce chemiluminescence upon reaction with superoxide (O2˙−) or peroxynitrite (ONOO−) but not with NO (17, 29, 46). However, we noticed that coelenterazine chemiluminescence and fluorescence responses were similar and thus in the present work we measured coelenterazine fluorescence to follow O2˙−/ONOO− production.

The ONOO− detection system.

Acutely isolated cardiac muscle cells from adult rats were suspended in Langendorff solution, incubated with 20 µM coelenterazine, washed, and distributed in 96-well plates. After background fluorescence was recorded, myocytes were exposed to 2.7 µM of the reactive nitrogen species (RNS) tetramethylammonium peroxynitrite (TMA-ONOO−). Results in Fig. 2 show that ONOO− produced a sudden increase in fluorescence that was not resolved in the 30-s time interval that followed its addition. This increase in fluorescence, typically from a background level of 150–200 arbitrary units (AU) to 300–350 AU, was not apparent when fresh TMA-ONOO− (dissolved in 10 mM KOH) was replaced with decomposed TMA-ONOO− (Fig. 2, open circles). Confocal images of the same cardiomyocyte before and after ONOO− exposure are included to illustrate the changes in fluorescence (Fig. 2, insets).

Fig. 2.

Time course of fluorescence changes in coelenterazine-loaded cardiac myocytes. Readings were recorded every 20 s, except for the first point after adding tetramethylammonium peroxynitrite (TMA-OONO−) solution, which was measured 30–40 s later. Data were normalized to background fluorescence and expressed as a percentage of the fluorescence measured with ONOO−. Also shown is the effect of decomposed TMA-ONOO− (see materials and methods). Symbols represent the mean ± SE for 5 (•) or 3 (○) experiments, all performed in triplicate. Pictures were obtained with a Carl Zeiss fluorescence microscope.

Unexpectedly, instead of increasing steadily, fluorescence levels reached a plateau that lasted at least 3 min in the continuous presence of ONOO−. Considering that the reaction with ONOO− irreversibly modifies the coelenterazine molecule (see discussion), such a behavior admits two alternative explanations: either coelenterazine within cardiomyocytes was saturated with ONOO− or ONOO− is a short-lived species. We assessed saturation of the fluorescent dye by performing sequential ONOO− additions to the same batch of coelenterazine-loaded myocytes. Consecutive ONOO− additions produced corresponding increases in fluorescence that progressively decreased in magnitude approaching saturation (Fig. 3A). Therefore, coelenterazine was not the limiting reagent when ONOO− was first added.

Fig. 3.

The nature of the fluorescence response to TMA-ONOO− treatment. A: fluorescence detection on cumulative addition of ONOO−. Increases in fluorescence were followed upon sequential addition (at the times indicated by arrows) of 2.7 µM TMA-ONOO− (in KOH) to cardiac myocytes loaded with 20 µM coelenterazine and suspended in a 0.2 mM calcium-containing Langendorff solution. Results are representative of 5 independent experiments; a.u., arbitrary units. B: time courses of ONOO− decay as a function of pH. The decay of 4 µM TMA-ONOO− dissolved either in 10 mM KOH (gray squares, n = 3) or added to a 0.2-mM calcium-containing Langendorff buffer (filled circles, n = 3) was followed spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 302 nm. Open circles represent the absorbance of 0.1 mM tetramethylammonium chloride (TMACl; n = 4) that was then subtracted. Single exponential functions were fitted to the data, from which rate constants k of 4.62 min−1 (Langendorff) and 0.014 min−1 (KOH) were obtained. Symbols represent the means ± SE for the indicated number of experiments. C: time course of fluorescence by ONOO− produced from a S-nitroso-N-acetyl-dl-penicillamine (SNAP) + pyrogallol mixture. At the time indicated by the arrow, a mixture of 10 µM SNAP plus 10 µM pyrogallol already releasing ONOO− (•) or only 10 µM SNAP (○) were added to coelenterazine-loaded cardiomyocytes suspended in calcium-containing Langendorff solution. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

In terms of the second explanation, the time course of ONOO− decay was followed by measuring absorbance at 302 nm in either 10 mM KOH (pH 12) or Langendorff buffer. Results in Fig. 3B show that ONOO− decays much faster in Langendorff buffer (t1/2 = 9 s) than in KOH (t1/2 = 2910 s). This finding is consistent with the knowledge that ONOO− is stable in alkaline media (4, 18, 24) and indicates that, for all practical purposes, the added ONOO− disappears within the first minute, i.e., we were basically exposing myocytes to a pulse of ONOO−. To further support this conclusion, we exposed coelenterazine-loaded cardiomyocytes to a mixture of 10 µM SNAP and 10 µM pyrogallol. SNAP spontaneously releases NO in solution and pyrogallol is a O2˙− supplier (47, 54). Equimolar combination of these compounds will result in the steady production of peroxynitrite according to NO + O2˙− ↔ ONOO−. Under these conditions, fluorescence shows an initial increase not resolved in time (similar to that observed with TMA-ONOO− treatment) but followed by a slower, linearly increasing phase (Fig. 3C). This second phase represents additional coelenterazine molecules reacting with ONOO− (and likely some O2˙−). Parallel application of SNAP alone confirmed that coelenterazine is not a reporter for NO production (Fig. 3C).

Effect of low L-Arg concentrations.

Since intracellular coelenterazine appears to be in excess, our design is well suited to detect further O2˙−/ONOO− production. Thus, after background fluorescence was recorded, myocytes were treated with 2.7 µM TMA-ONOO− and the system was allowed to reach a plateau in fluorescence (Fig. 4A). After 3 min, enough L-Arg to yield a final concentration of 50 µM was added to the well plates. L-Arg enters cardiac muscle cells through high- and low-affinity CATs (28). Once inside, among other roles, L-Arg becomes the substrate for NO synthesis via NOS activity. However, 50 µM L-Arg further increased fluorescence on top of the TMA-ONOO− plateau (Fig. 4A), suggesting that this concentration of L-Arg mediated the endogenous synthesis of O2˙− rather than NO. Another aliquot of coelenterazine-loaded myocytes from the same batch was treated with 200 µM L-Arg. In this case, no further increase in fluorescence was observed on top of the plateau (Fig. 4A), suggesting that this L-Arg concentration was enough to keep NOS activity in a NO-producing mode. L-Arg transport and NOS activity were involved in the effect observed with 50 µM L-Arg, since 50 µM D-Arg, neither a transported species nor a NOS substrate, and 50 µM L-Lys, a transported species but not a NOS substrate, both failed to produce an increase in fluorescence (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, the increase in fluorescence produced with 50 µM L-Arg was completely blocked by the general NOS inhibitor l-NAME (Fig. 4C). The L-Arg concentration dependence of fluorescence increase indicates that the lower the L-Arg concentration, the larger the increase in fluorescence, i.e., the more O2˙−/ONOO− was produced (Fig. 4D). In fact, the change in fluorescence was found to be a decreasing function of L-Arg concentration with abscissa equal to 130 µM (Fig. 4E). This abscissa value represents the minimal L-Arg concentration that produces NO rather than O2˙− under these experimental conditions (2.7 µM TMA-ONOO−).

Fig. 4.

Effect of l-arginine (L-Arg) on peroxynitrite-induced fluorescence. A: time courses of fluorescence changes at 50 (○) and 200 µM L-Arg (•). The arrow shows the time at which L-Arg was added. Symbols represent the means ± SE of 5 experiments performed in triplicate for each L-Arg concentration. B: time courses of fluorescence changes in the presence of 50 µM D-Arg (•) or L-Lys (○). Symbols represent the means ± SE of 5 experiments for D-Arg and 3 for L-Lys, each performed in triplicate. C: effect of 50 μM L-Arg in the absence (○, n = 5) and presence of 1 mM l-NAME (•, n = 3). Cells were preincubated with l-NAME for 5 min before adding peroxynitrite. D: L-Arg concentration dependence of average fluorescence increases for the range 20–200 μM. E: increase in fluorescence above the baseline as a function of L-Arg concentration. Symbols (as well as bars in D) represent the means ± SE of 24 time points, each of which summarizes the values from 5 experiments at those same times. The line through the data points is the best-fit linear regression, with an x-axis intercept of 130.3 µM.

Dependence on added ONOO−.

The concentration of added TMA-ONOO− must necessarily have an effect on the amount of L-Arg needed to produce an increase in fluorescence. Thus experiments such as those presented in Fig. 4, D and E, were carried out with myocytes initially exposed to different concentrations of ONOO−. It was found that the lower the ONOO− concentration, the lower the L-Arg concentration required to produce increases in fluorescence (Fig. 5A). Linear regression analysis at each ONOO− concentration yielded abscissa values that were a hyperbolic increasing function of ONOO− concentration (Fig. 5B). The ordinate of this hyperbola at [ONOO−] = 0 was found to have a value of 64 ± 16 µM. This value represents the extracellular L-Arg concentration below which NOS begins synthesizing O2˙−, eventually leading to ONOO− production.

Fig. 5.

Peroxynitrite concentration dependence of L-Arg-induced increases in fluorescence. A: fluorescence, expressed as a percent of increase over the level obtained at each ONOO− concentration, as a function of L-Arg concentration. Symbols, which are time averages, correspond to 0.53 (•), 2.7 (○), 13 (▼), and 67 (△) µM ONOO− and represent the means ± SE of 5 experiments for each concentration. Lines through the data points represent linear regressions, with 0.955 < R2 < 0.997. B: L-Arg concentration that produces nitric oxide synthase (NOS)-mediated endogenous ONOO−. Best-fit abscissa values from A are plotted as a function of ONOO− concentration. The following hyperbolic function was fitted to the data: Abs = y0 + (Absmax [ONOO−]/Km + [ONOO−]), yielding a value of y0 = 64 µM. This value represents the minimal L-Arg concentration required for NOS to produce NO in the absence of exogenous ONOO−.

Direct L-Arg concentration dependence.

Once the detection system and the L-Arg and ONOO− concentration dependence of fluorescence were validated, it was anticipated that limiting concentrations of L-Arg would themselves produce fluorescence increases. Therefore, after background fluorescence was recorded, coelenterazine-loaded cardiomyocytes were exposed to 20, 50, or 100 µM L-Arg. The increase in fluorescence was larger at lower L-Arg concentrations, displaying an initial fast phase not resolved in time followed by a much slower, mildly increasing second component (Fig. 6). Notice that, according to the error bars, changes in fluorescence brought about by 100 µM L-Arg were not significantly different from zero, so that the L-Arg concentration that first triggers O2˙−/ONOO− production must fall within the range 50 µM < [L-Arg] < 100 µM, a result consistent with the value found in the previous section. Two controls are also presented in Fig. 6. First, a complete block of fluorescence increase was observed when myocytes were incubated with 1 mM l-NAME before being exposed to 20 μM L-Arg (open diamonds). This result clearly indicates the involvement of NOS activity in the fluorescence increases observed without the inhibitor. Second, myocyte incubation with 200 μM uric acid, a well-known ONOO− scavenger (Ref. 49 and references therein), also prevented fluorescence increases in the presence of 20 μM L-Arg (gray squares). Except for an initial mild increase, likely showing that O2˙− production precedes that of ONOO−, this lack of response further confirms the relationship between low L-Arg concentrations and ONOO− production.

Fig. 6.

Effect of low concentrations of L-Arg on fluorescence produced by coelenterazine-loaded cardiac myocytes. Fluorescence increases at each L-Arg concentration were converted into percentages after subtracting the corresponding baselines. Symbols represent the means ± SE of 3 time courses for each of the L-Arg concentrations shown above the respective curves. Also shown are time courses obtained in the presence of 20 μM L-Arg for myocytes that were incubated with 1 mM l-NAME (open diamonds) or 200 μM uric acid (gray squares). Symbols represent the means of 3 experiments for each condition but error bars were omitted for the sake of clarity.

A more realistic estimate.

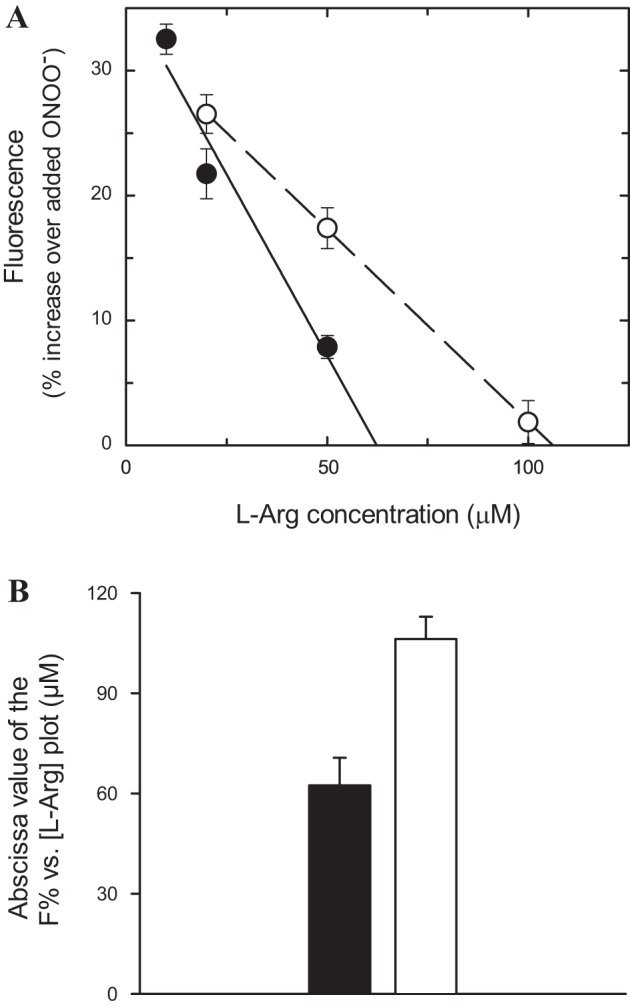

A frequently neglected fact is that the blood that irrigates cardiac myocytes contains L-Arg but also L-Lys and l-ornithine (L-Orn), which are equally efficiently transported by the system-y+ cationic amino acid carriers present on the cell membrane (13, 40). Considering a plasma concentration of 250 µM for L-Arg and L-Lys, and 100 µM for L-Orn (39, 48), and assuming that every L-Arg molecule that enters the cell is converted into NO, a maximum of two out of five transport events will likely result in NO production. This scenario suggests that a larger extracellular L-Arg concentration would be required to avoid NOS-mediated O2˙−/ONOO− production. To determine this new, more realistic L-Arg concentration, experiments similar to those described in Figs. 4 and 5 were performed in the presence of 250 µM L-Lys and 100 µM L-Orn. A 533-nM TMA-ONOO− concentration was selected because its L-Arg abscissa value represents a good approximation to that extrapolated at zero ONOO− (Fig. 5B). The L-Arg concentration dependence of fluorescence increase is plotted in Fig. 7A together with the corresponding curve in the absence of L-Lys and L-Orn from Fig. 5A. Clearly, the presence of these two amino acids shifted the curve to the right, indicating that a larger L-Arg concentration will still deviate NOS activity toward the production of aberrant by-products. Linear regression yielded an abscissa value of 106 ± 7 µM L-Arg in the presence of L-Lys and L-Orn. This value is, in average, ~70% larger than that obtained in the absence of these amino acids (Fig. 7B). Therefore, at extracellular L-Arg concentrations of ~100 µM or lower, some NOS units will switch from NO to O2˙− production in the presence of physiological concentrations of other cationic amino acids.

Fig. 7.

Effect of physiological levels of L-Lys and L-Orn on L-Arg-mediated increases in fluorescence. A: fluorescence, expressed as a percentage of increase over the level obtained with 0.53 µM ONOO−, as a function of L-Arg concentration. Symbols correspond to the absence (•) and the presence of 250 µM L-Lys plus 100 µM L-Orn (○) and represent time averages of the means ± SE of 5 experiments for each concentration. Lines through the data points represent linear regressions, with R2 values of 0.957 and 0.999 for the absence and the presence of L-Lys and L-Orn, respectively. B: abscissa values from the linear regression analysis. Closed bars represent the absence and open bars represent the presence of 250 µM L-Lys plus 100 µM L-Orn.

The NOS isoform.

A pertinent question relates to the identity of the NOS isoform that is responsible for ROS/RNS generation in adult rat cardiomyocytes. Western blots from freshly isolated myocyte (> 95% purity) lysates treated with specific antibodies (see materials and methods) showed a prominent band for the endothelial isoform (eNOS) whereas the neuronal isoform (nNOS) was hardly detected (Fig. 8A). Consistent with this finding, 20 µM of the NOS inhibitor 7-NINA, reported to block nNOS in vitro with an IC50 of 0.47 µM (36) without affecting eNOS (43, 44), failed to reduce the increase in fluorescence produced by direct treatment of myocytes with 20 µM L-Arg, an increase that was completely prevented by preincubation with 1 mM of the NOS general inhibitor l-NAME (Fig. 8B). These results suggest that eNOS is responsible for NO and O2˙−/ONOO− production in adult rat cardiomyocytes.

Fig. 8.

Immunohistochemical and functional characterization of NOS isoforms. A: Western blots for NOS isoforms in rat cardiac ventricular myocytes (CM). Positive controls: endothelial (e)NOS, human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC P7); neuronal (n)NOS, mouse whole brain tissue homogenate. B: pharmacological manipulations. Acutely isolated myocytes were loaded with coelenterazine and incubated for 5–6 min with either Langendorff buffer (∘), 20 µM 7-NINA (•), or 1 mM l-NAME (△). Treatment groups were then exposed to 20 µM L-Arg. Background fluorescence was subtracted from all 3 groups. The displayed behavior is representative of 3 experiments each performed in duplicate.

Effect of endogenous ONOO−.

To test the underlying hypothesis that ONOO− is the ultimate by-product of NOS aberrant activity at limiting L-Arg concentrations, we investigated the presence of ONOO− fingerprints, i.e., the nitration in position 3 of aromatic rings in protein tyrosine residues. Nitrotyrosine formation was monitored by immunocytochemistry. Incubation of cardiomyocytes for 30 min with 20 µM L-Arg resulted in a prominent 3-NO2-Tyr staining (Fig. 9, top left), an effect that was ameliorated in a dose-dependent manner by increasing the concentration of external L-Arg (Fig. 9, top middle and right). The staining observed in the presence of 20 µM L-Arg was completely blocked by preincubation of the primary antibody with 1 mM nitrotyrosine, confirming the specificity of the immunological reaction (Fig. 9, bottom left). This staining was also prevented by preincubating the cardiomyocytes with 1 mM l-NAME (not shown, but see Table 1), confirming the involvement of NOS activity in nitrotyrosine formation. Interestingly, incubation of myocytes with L-Arg-free Langendorff buffer, a condition that could be thought of as the lowest possible L-Arg concentration, resulted in a minimal staining (Fig. 9, bottom middle) that was not significantly different from that measured with nitrotyrosine. This is likely due to the observation that NOS will not produce any NO in the complete absence of L-Arg (see discussion). As a positive control, myocytes were exposed for 30 min to the ONOO−-producing mixture 10 µM SNAP plus 10 µM pyrogallol (Fig. 9, bottom right).

Fig. 9.

Immunocytochemical detection of nitrotyrosine formation. Isolated myocytes plated on 6-well plates were exposed for 30 min to the treatments described and then incubated with protein G purified mouse monoclonal anti-3-nitrotyrosine IgG followed with Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse IgG. Nuclei were identified with DAPI although this staining was not included in the image analysis. Confocal images (×40 magnification) were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope. All solutions were prepared in Langendorff buffer; for the ONOO− treatment (bottom right), myocytes were exposed to a mixture of 10 µM of SNAP + 10 µM pyrogallol. Calibration bar, 20 μm.

Table 1.

Immunocytochemical analysis of 3-NO2-tyrosination in cardiac myocytes

| Treatment | Mean Intensity ± SE* (Average Pixel Value) | Percentage of ONOO− Fluorescence After Subtracting Buffer |

|---|---|---|

| ONOO− | 2,316 ± 156 | 100 |

| 20 µM L-Arg | 1,756 ± 110 | 72 ± 8 |

| 100 µM L-Arg | 870 ± 58 | 27 ± 4 |

| 2 mM L-Arg | 524 ± 58 | 10 ± 3 |

| 20 µM L-Arg + 1 mM NO2-Tyr | 386 ± 25 | 3 ± 2† |

| 20 µM L-Arg + 1 mM l-NAME | 397 ± 30 | 3 ± 2‡ |

| Langendorff buffer | 330 ± 28 | 0 |

n = 10 myocytes for each treatment condition. †,‡Not significantly different from zero.

Quantification of red fluorescence was carried out by determining mean intensity values derived from intensity histograms, i.e., the statistical mean of intensity values of pixels, from confocal images and NIS element measurements. Results from several cells, summarized in Table 1, show that 20 µM extracellular L-Arg produced an average of ~75% of the maximal 3-NO2-Tyr formation estimated by direct cardiomyocyte exposure to ONOO−. 3-NO2-tyrosination was further reduced to ~25% by increasing the concentration of L-Arg to 100 µM and practically abolished at millimolar L-Arg.

DISCUSSION

A novel experimental design was set up for the detection of O2˙−/ONOO− production in cardiac myocytes to determine the levels of extracellular L-Arg that trigger NOS biosynthesis of these by-products. The fluorescent dye coelenterazine, when loaded into myocytes, proved to be sensitive to both externally added ONOO− and its endogenous production mediated by limiting levels of L-Arg. Although addition of TMA-ONOO−, SNAP + pyrogallol, or limiting L-Arg concentrations all increased fluorescence in coelenterazine-loaded myocytes, the initial response and secondary fluorescence increases appear to be of different nature. Exposure to TMA-ONOO− in Langendorff buffer (pH 7.2) resulted in a sudden increase in fluorescence followed by a plateau. This behavior likely represents only modification of the most accessible pool of coelenterazine molecules given the short half-life of ONOO− at this pH value. In fact, mass spectrometry assays showed nitration in position 3 (meta) of aromatic rings in the coelenterazine molecule (see materials and methods) upon brief exposure to TMA-ONOO− in Langendorff buffer (Li H, Peluffo RD, unpublished results). The SNAP + pyrogallol ONOO− producing system showed fast and slow fluorescence components. The latter component may represent ROS/RNS reaction with coelenterazine molecules located in more distant and/or less accessible compartments. A similar explanation applies to the endogenous production of O2˙−/ONOO− mediated by limiting levels of extracellular L-Arg. However, intracellular diffusion of L-Arg molecules to reach more distant/less accessible pools of NOS enzyme must also be considered in this case as the reason for the second, slower component.

The effect of L-Arg showed an inversely proportional concentration dependence on fluorescence. D-Arg, which is not transported by system-y+ members, and L-Lys, which although transported is not a substrate for NO synthesis, did not increase fluorescence at similar concentrations. The notion that the increase in fluorescence requires NOS activity was confirmed by the lack of effect when 50 μM L-Arg was applied to myocytes preincubated with the NOS inhibitor l-NAME. Altogether, these findings strongly suggest that limiting L-Arg concentrations are promoting the synthesis of O2˙−, which by itself or through the reaction NO + O2˙− → ONOO− enhances coelenterazine fluorescence.

Our quantification of “limiting substrate conditions” indicates that, in the absence of externally added ONOO−, a plasma [L-Arg] ≤ 64 µM will result in ROS/RNS production in cardiac myocytes. However, given the presence in the extracellular fluid of physiological concentrations of other cationic amino acids that efficiently compete with L-Arg transport (13, 28, 40), a more realistic limiting value of 106 ± 7 µM L-Arg was obtained in the simultaneous presence of L-Lys and L-Orn. Therefore, at extracellular [L-Arg] ≤ 100 µM, while some NOS units will still produce NO, a subset of this enzyme will begin producing O2˙−. It is anticipated that the lower the L-Arg concentration the larger the recruited number of O2˙−-synthesizing NOS units. These observations also fit well with the detection of H2O2 formation at concentrations of L-Arg below 100 µM using purified brain NOS preparations (21). Of particular note, even if a limiting value of 64 µM L-Arg is considered, we can see the “arginine paradox” at work (6, 27, 32), provided that this [L-Arg] is ~20-fold larger than the K0.5 for L-Arg activation of constitutive NOS activity in vitro under saturating conditions for cosubstrates and cofactors (Ref. 16 and references therein).

Western blot experiments detected eNOS (NOS3) as the constitutive isoform to be almost exclusively present in isolated rat cardiac ventricular myocytes. This finding, although indirect, points to eNOS as responsible for ROS/RNS production in cardiac muscle cells. The lack of effect of the fairly selective nNOS inhibitor 7-NINA on L-Arg-induced fluorescence further supports this conclusion.

In an independent approach, immunocytochemistry experiments clearly show that the lower the extracellular L-Arg concentration the stronger the 3-NO2-Tyr staining in rat cardiac myocytes, a fingerprint for ONOO− production (12). These results demonstrate that limiting concentrations of L-Arg are able to produce substantial amounts of a Tyr-nitrating agent and seem to be at variance with previous reports indicating the lack of Tyr nitration by ONOO− generated from NO and O2˙− at pH 7.4 in vitro (41). Furthermore, Tyr nitration of proteins upon exposure to low concentrations of extracellular L-Arg took place despite the anticipated presence of physiological levels of intracellular GSH and SOD that might diminish ONOO− formation in acutely isolated cardiac myocytes.

Interestingly, incubation with 100 µM L-Arg did not completely abolish the nitration of Tyr residues in cardiac muscle proteins although it reduced immunostaining to roughly one-third of that obtained with 20 µM L-Arg. A possible explanation to reconcile this finding with our threshold L-Arg value of 106 µM is that the 30 min-long myocyte incubation in immunocytochemistry assays could have uncovered additional sources for the production of O2˙−/ONOO− such as mitochondria (42). This mitochondrial ROS/RNS production that has been reported to be responsible for the 3-NO2-tyrosination of several critical proteins in the mitochondrial matrix, inner and outer membranes, as well as the intermembrane space (42), might have a more complex relationship with extracellular L-Arg levels (54).

Two additional features of our immunocytochemistry assays are noticeable. First, millimolar L-Arg concentrations prevented immunostaining of 3-NO2-tyrosinated proteins in cardiac myocytes, a result that can be interpreted as a full inhibition of O2˙−/ONOO− production by these concentrations of L-Arg. This observation is consistent with our previous reports showing that millimolar concentrations of extracellular L-Arg promote full production of NO by NOS (40, 55) and might explain the finding that improvement of both clinical symptoms of cardiovascular disease and the outcome of patients with congestive heart failure are observed upon L-Arg supplementation but only when its plasma levels reach concentrations of 3–6 mM (7, 25). In agreement, skeletal muscle from rabbits treated with ~2 mM L-Arg showed both inhibition of NOS-mediated O2˙− production and reduction of ischemia/reperfusion injury (22).

The second feature is the lack of staining when myocytes were incubated with L-Arg-free Langendorff buffer, a condition that could be visualized as the lowest possible L-Arg concentration and thus should result in full production of ROS/RNS and nitrotyrosine fingerprints. Previous studies using a similar immunocytochemical approach on nNOS-overexpressing HEK 293 cells found prominent nitrotyrosine immunostaining upon prolonged incubation in L-Arg-free medium (51). This treatment resulted in an estimated intracellular L-Arg of ~16 µM after 24 h. We have previously reported the presence of high-affinity/low-capacity and low-affinity/high-capacity passive CATs functioning in parallel in rat cardiac ventricular myocytes (28). In particular, due to its high capacity, the low-affinity transporter was shown to be responsible of at least 50% of total cationic amino acid transport in this cell type (28). To the best of our knowledge, a low-affinity/high-capacity component of L-Arg transport has not been reported in HEK cells. Therefore, passive L-Arg efflux could be much more efficient in cardiomyocytes incubated with L-Arg-free medium thus completely depleting intracellular pools in the ~1.5 h of total myocyte manipulations. With L-Arg concentrations approaching zero, NOS isoforms will only produce O2˙− and H2O2 (3) and the lack of NO will prevent both ONOO− formation and the subsequent 3-nitration of protein Tyr residues. In addition, calcium resting levels in noncontracting cardiac muscle cells, reported to be ~100 nM (30), are below the K0.5 values for Ca-CaM activation of constitutive NOS isoforms (38). In this regard, when the intracellular Ca concentration increases to ~1 μM with each heartbeat, fully functional NOS units will be better suited to produce harmful O2˙−/ONOO− by-products under limiting concentrations of L-Arg.

Constitutive NOS isoforms appear to be highly conserved between rats and humans (>90% amino acid identity) (16), and circulating L-Arg plasma levels have been reported to be similar in these two species (39, 48). Accordingly, the present results suggest routine evaluation of L-Arg plasmatic levels in patients and provide a lower concentration limit for corrective therapeutic interventions in the clinical practice.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-076392 (to R. D. Peluffo). The support from Universidad de la República (Uruguay) and the Uruguayan National Agency for Research and Innovation (ANII) is also acknowledged.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.R. performed experiments; J.R. and R.D.P. analyzed data; J.R. and R.D.P. edited and revised manuscript; J.R. and R.D.P. approved final version of manuscript; R.D.P. conceived and designed the research; R.D.P. interpreted results of experiments; R.D.P. prepared figures; R.D.P. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the technical assistance of Dr. Ruifang Zheng and the help of Drs. Patrick Gonzalez and Diego Fraidenraich (Dept. of Cell Biology and Molecular Medicine, Rutgers Biomedical and Health Sciences-New Jersey Medical School) with image analysis of cardiac myocytes.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abumrad NN, Barbul A. The use of arginine in clinical practice. In: Metabolic and therapeutic aspects of amino acids in clinical nutrition (Cynober LA, ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC, 2004, p. 595–611. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvarez B, Radi R. Peroxynitrite reactivity with amino acids and proteins. Amino Acids 25: 295–311, 2003. doi: 10.1007/s00726-003-0018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrew PJ, Mayer B. Enzymatic function of nitric oxide synthases. Cardiovasc Res 43: 521–531, 1999. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00115-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckman JS, Beckman TW, Chen J, Marshall PA, Freeman BA. Apparent hydroxyl radical production by peroxynitrite: implications for endothelial injury from nitric oxide and superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 1620–1624, 1990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beckman JS, Koppenol WH. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 271: C1424–C1437, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bode-Böger SM, Scalera F, Ignarro LJ. The L-arginine paradox: importance of the L-arginine/asymmetrical dimethylarginine ratio. Pharmacol Ther 114: 295–306, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Böger RH, Bode-Böger SM. The clinical pharmacology of L-arginine. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 41: 79–99, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borbély A, Tóth A, Edes I, Virág L, Papp JG, Varró A, Paulus WJ, van der Velden J, Stienen GJ, Papp Z. Peroxynitrite-induced alpha-actinin nitration and contractile alterations in isolated human myocardial cells. Cardiovasc Res 67: 225–233, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bredt DS, Snyder SH. Nitric oxide: a physiologic messenger molecule. Annu Rev Biochem 63: 175–195, 1994. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.63.070194.001135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheung PY, Danial H, Jong J, Schulz R. Thiols protect the inhibition of myocardial aconitase by peroxynitrite. Arch Biochem Biophys 350: 104–108, 1998. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Creager MA, Gallagher SJ, Girerd XJ, Coleman SM, Dzau VJ, Cooke JP. L-arginine improves endothelium-dependent vasodilation in hypercholesterolemic humans. J Clin Invest 90: 1248–1253, 1992. doi: 10.1172/JCI115987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crow JP, Ischiropoulos H. Detection and quantitation of nitrotyrosine residues in proteins: in vivo marker of peroxynitrite. Methods Enzymol 269: 185–194, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(96)69020-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devés R, Boyd CA. Transporters for cationic amino acids in animal cells: discovery, structure, and function. Physiol Rev 78: 487–545, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ducrocq C, Blanchard B, Pignatelli B, Ohshima H. Peroxynitrite: an endogenous oxidizing and nitrating agent. Cell Mol Life Sci 55: 1068–1077, 1999. doi: 10.1007/s000180050357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferdinandy P, Danial H, Ambrus I, Rothery RA, Schulz R. Peroxynitrite is a major contributor to cytokine-induced myocardial contractile failure. Circ Res 87: 241–247, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.3.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Förstermann U, Closs EI, Pollock JS, Nakane M, Schwarz P, Gath I, Kleinert H. Nitric oxide synthase isozymes. Characterization, purification, molecular cloning, and functions. Hypertension 23: 1121–1131, 1994. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.23.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gambim MH, do Carmo AO, Marti L, Veríssimo-Filho S, Lopes LR, Janiszewski M. Platelet-derived exosomes induce endothelial cell apoptosis through peroxynitrite generation: experimental evidence for a novel mechanism of septic vascular dysfunction. Crit Care 11: R107, 2007. doi: 10.1186/cc6133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldstein S, Czapski G, Lind J, Merényi G. Effect of *NO on the decomposition of peroxynitrite: reaction of N2O3 with ONOO−. Chem Res Toxicol 12: 132–136, 1999. doi: 10.1021/tx9802522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gross SS, Wolin MS. Nitric oxide: pathophysiological mechanisms. Annu Rev Physiol 57: 737–769, 1995. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.003513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hecker M, Sessa WC, Harris HJ, Anggård EE, Vane JR. The metabolism of L-arginine and its significance for the biosynthesis of endothelium-derived relaxing factor: cultured endothelial cells recycle L-citrulline to L-arginine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 8612–8616, 1990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinzel B, John M, Klatt P, Böhme E, Mayer B. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent formation of hydrogen peroxide by brain nitric oxide synthase. Biochem J 281: 627–630, 1992. doi: 10.1042/bj2810627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huk I, Nanobashvili J, Neumayer C, Punz A, Mueller M, Afkhampour K, Mittlboeck M, Losert U, Polterauer P, Roth E, Patton S, Malinski T. L-arginine treatment alters the kinetics of nitric oxide and superoxide release and reduces ischemia/reperfusion injury in skeletal muscle. Circulation 96: 667–675, 1997. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.96.2.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ischiropoulos H, al-Mehdi AB. Peroxynitrite-mediated oxidative protein modifications. FEBS Lett 364: 279–282, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00307-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kissner R, Koppenol WH. Product distribution of peroxynitrite decay as a function of pH, temperature, and concentration. J Am Chem Soc 124: 234–239, 2002. doi: 10.1021/ja010497s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koifman B, Wollman Y, Bogomolny N, Chernichowsky T, Finkelstein A, Peer G, Scherez J, Blum M, Laniado S, Iaina A, Keren G. Improvement of cardiac performance by intravenous infusion of L-arginine in patients with moderate congestive heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 26: 1251–1256, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lokuta AJ, Maertz NA, Meethal SV, Potter KT, Kamp TJ, Valdivia HH, Haworth RA. Increased nitration of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in human heart failure. Circulation 111: 988–995, 2005. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156461.81529.D7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loscalzo J. An experiment of nature: genetic L-arginine deficiency and NO insufficiency. J Clin Invest 108: 663–664, 2001. doi: 10.1172/JCI13848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lu X, Zheng R, González J, Gaspers L, Kuzhikandathil E, Peluffo RD. L-lysine uptake in giant vesicles from cardiac ventricular sarcolemma: two components of cationic amino acid transport. Biosci Rep 29: 271–281, 2009. doi: 10.1042/BSR20080159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lucas M, Solano F. Coelenterazine is a superoxide anion-sensitive chemiluminescent probe: its usefulness in the assay of respiratory burst in neutrophils. Anal Biochem 206: 273–277, 1992. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90366-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marks AR. Calcium and the heart: a question of life and death. J Clin Invest 111: 597–600, 2003. doi: 10.1172/JCI18067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massion PB, Feron O, Dessy C, Balligand JL. Nitric oxide and cardiac function: ten years after, and continuing. Circ Res 93: 388–398, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000088351.58510.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDonald KK, Zharikov S, Block ER, Kilberg MS. A caveolar complex between the cationic amino acid transporter 1 and endothelial nitric-oxide synthase may explain the “arginine paradox”. J Biol Chem 272: 31213–31216, 1997. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendes Ribeiro AC, Brunini TM, Ellory JC, Mann GE. Abnormalities in L-arginine transport and nitric oxide biosynthesis in chronic renal and heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 49: 697–712, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00267-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mihm MJ, Bauer JA. Peroxynitrite-induced inhibition and nitration of cardiac myofibrillar creatine kinase. Biochimie 84: 1013–1019, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(02)00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitra R, Morad M. A uniform enzymatic method for dissociation of myocytes from hearts and stomachs of vertebrates. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 249: H1056–H1060, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moore PK, Babbedge RC, Wallace P, Gaffen ZA, Hart SL. 7-Nitro indazole, an inhibitor of nitric oxide synthase, exhibits anti-nociceptive activity in the mouse without increasing blood pressure. Br J Pharmacol 108: 296–297, 1993. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1993.tb12798.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris SM, Jr. Arginine: beyond protein. Am J Clin Nutr 83, Suppl: 508S–512S, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nathan C. Nitric oxide as a secretory product of mammalian cells. FASEB J 6: 3051–3064, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noeh FM, Wenzel A, Harris N, Milakofsky L, Hofford JM, Pell S, Vogel WH. The effects of arginine administration on the levels of arginine, other amino acids and related amino compounds in the plasma, heart, aorta, vena cava, bronchi and pancreas of the rat. Life Sci 58: PL131–PL138, 1996. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(96)80013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peluffo RD. L-Arginine currents in rat cardiac ventricular myocytes. J Physiol 580: 925–936, 2007. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.125054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfeiffer S, Mayer B. Lack of tyrosine nitration by peroxynitrite generated at physiological pH. J Biol Chem 273: 27280–27285, 1998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.42.27280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Radi R, Cassina A, Hodara R, Quijano C, Castro L. Peroxynitrite reactions and formation in mitochondria. Free Radic Biol Med 33: 1451–1464, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)01111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rairigh RL, Storme L, Parker TA, Le Cras TD, Markham N, Jakkula M, Abman SH. Role of neuronal nitric oxide synthase in regulation of vascular and ductus arteriosus tone in the ovine fetus. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 278: L105–L110, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramachandran J, Schneider JS, Crassous PA, Zheng R, Gonzalez JP, Xie LH, Beuve A, Fraidenraich D, Peluffo RD. Nitric oxide signalling pathway in Duchenne muscular dystrophy mice: up-regulation of L-arginine transporters. Biochem J 449: 133–142, 2013. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reifenberger MS, Arnett KL, Gatto C, Milanick MA. The reactive nitrogen species peroxynitrite is a potent inhibitor of renal Na-K-ATPase activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 295: F1191–F1198, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90296.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tarpey MM, White CR, Suarez E, Richardson G, Radi R, Freeman BA. Chemiluminescent detection of oxidants in vascular tissue. Lucigenin but not coelenterazine enhances superoxide formation. Circ Res 84: 1203–1211, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.84.10.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trochu JN, Bouhour JB, Kaley G, Hintze TH. Role of endothelium-derived nitric oxide in the regulation of cardiac oxygen metabolism: implications in health and disease. Circ Res 87: 1108–1117, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.12.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Haeften TW, Konings CH. Arginine pharmacokinetics in humans assessed with an enzymatic assay adapted to a centrifugal analyzer. Clin Chem 35: 1024–1026, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whiteman M, Halliwell B, Darley-usmar V. Protection against peroxynitrite-dependent tyrosine nitration and α1-antiproteinase inactivation by ascorbic acid. A comparison with other biological antioxidants. Free Radic Res 25: 275–283, 1996. doi: 10.3109/10715769609149052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu GY, Brosnan JT. Macrophages can convert citrulline into arginine. Biochem J 281: 45–48, 1992. doi: 10.1042/bj2810045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xia Y, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Snyder SH, Zweier JL. Nitric oxide synthase generates superoxide and nitric oxide in arginine-depleted cells leading to peroxynitrite-mediated cellular injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 6770–6774, 1996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xia Y, Tsai AL, Berka V, Zweier JL. Superoxide generation from endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. A Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent and tetrahydrobiopterin regulatory process. J Biol Chem 273: 25804–25808, 1998. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xia Y, Zweier JL. Superoxide and peroxynitrite generation from inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 6954–6958, 1997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xie YW, Wolin MS. Role of nitric oxide and its interaction with superoxide in the suppression of cardiac muscle mitochondrial respiration. Involvement in response to hypoxia/reoxygenation. Circulation 94: 2580–2586, 1996. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.94.10.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou J, Kim DD, Peluffo RD. Nitric oxide can acutely modulate its biosynthesis through a negative feedback mechanism on l-arginine transport in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C230–C239, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00077.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]