Abstract

Objective:

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is associated with thromboembolic events. Compromised left atrial appendage (LAA) function due to left ventricular (LV) performance abnormality, often present in patients with OSA, may play an important role. The purpose of this study is to evaluate LV and LAA mechanical functions during sinus rhythm (SR) in patients with OSA.

Methods:

LV and LAA functions were assessed in 43 OSA patients and compared with that of 20 control patients in SR. Tissue Doppler velocities of the LAA apex and emptying velocities (EV) of LAA were obtained on parasternal short-axis view.

Results:

The baseline clinical characteristics were similar except for AHI (apnea-hypopnea index), minimal SaO2, mean SaO2, hypertension, and body-surface area. Most of the LV echocardiographic parameters significantly deteriorated in OSA patients in comparison with those in the control group. LAA EV, LAA systolic relaxation velocity (SM), LAA early-diastolic velocity (EM), LAA contraction velocity (AM), left atrial (LA) minimum volume index, LA ejection fraction, LA conduit volume index, and LA reservoir volume index were lower in OSA patients compared with those in the control group (p<0.05). LAA AM was negatively correlated with AHI and the ratio of peak early diastolic flow velocity (E) to early-diastolic (E’) and positively correlated with LA conduit volume (p<0.05). Multiple predictors for LAA AM were AHI, presence of diastolic dysfunction, and E/E’ values (p<0.05).

Conclusion:

LAA mechanical function is significantly depressed in patients with OSA and SR. LAA dysfunction may predispose these patients to thromboembolic events. The evaluation of LAA mechanical function by tissue Doppler study using transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) may become an alternative for routine work-up in OSA patients.

Keywords: diastolic dysfunction, left atrial appendage, obstructive sleep apnea, sinus rhythm, tissue Doppler echocardiography

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a highly prevalent disorder that is characterized by repetitive episodes of airflow cessation (apnea) or reduction (hypopnea) despite persistent thoracic and abdominal respiratory efforts during sleep. OSA is generally defined as five or more apneas and/or hypopneas per hour of sleep [apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) >5] that is assessed by a cardiorespiratory or full polysomnography (PSG) recording (1).

Clinical and epidemiological data suggests an independent association between OSA and mainly systemic hypertension but also with pulmonary hypertension and other cardiovascular diseases such as coronary artery disease, cardiac arrhythmias, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death (2). OSA is also found to be an independent risk factor for thromboembolic events (3). Left atrial (LA) function, especially that of the LA appendage (LAA), may be one of the most important determinants of thromboembolic events because LAA is almost always the site of thrombus formation (4, 5).

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) can provide information on LAA function (4). LAA relaxation, for example, is impaired with aging and accompanied by early diastolic left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and chronic overload of the LA (6). Tissue Doppler imaging (TDI) is an ideal tool for evaluating regional myocardial function and has been validated on regional left ventricular and left atrial function assessment (7-9). LAA mechanics are influenced by changes in LV function. LAA early diastolic flows are related to LV contraction and relaxation (10). Based on these considerations, LAA function may deteriorate because of LV performance abnormality, which is often present in patients with OSA (11, 12). Proposed mechanisms that affect LV performance in patients with OSA include several mechanical, neurohumoral, inflammatory, endothelial, and oxidative effects (13). The purpose of this study is to evaluate LV and LAA mechanical functions in patients with OSA and sinus rhythm (SR).

Methods

The study cohort consisted of 63 patients recruited from the Sleep Disorders Center of Dışkapı Yıldırım Beyazıt Research and Educational Hospital. These patients were referred for a clinically indicated sleep study. Data on demographic characteristics, sleep and medical history, and medication use were obtained with the use of a standardized questionnaire before the overnight polysomnogram. The sleep questionnaire included questions on history of snoring and the relationship of snoring with position, choking, witnessed apnea, sleep fragmentation, nocturia, night sweating, morning tiredness, and headache. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale was used to report subjective daytime sleepiness. Data regarding risk factors for coronary artery disease included a history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or hyperlipidemia reported by the patient on the baseline medical questionnaire, noted in the file or both. Smoking habit was also documented on the routine baseline questionnaire. The clinical evaluation of patients involved internal medicine, neurologic, and psychiatric clinical reviews by physicians. Body mass index (BMI), neck circumference, and craniofacial measurements (overjet, overbite, position of mandible and maxilla and soft palate, and Mallampati scores) were obtained. Patients with sleep disorders other than OSA such as central sleep apnea, periodic limb movement syndrome, or narcolepsy were excluded from the study. AHI ≥5 was diagnosed as OSA and AHI <5 was diagnosed as non-OSA. Twenty-four patients with severe OSA (defined as AHI ≥30) (age, 43.1±11.0 years; mean AHI, 60.9±21.3; 17 men and 7 women), 19 patients with mild-to-moderate OSA (defined as AHI 5-29) (age, 41.4±12.6 years; AHI, 14.9±8.3; 12 men and 5 women), and 20 control subjects (age, 42.9±13.1 years; AHI, 2.7±1.0; 11 men and 9 women) were studied.

Normal sinus rhythm was confirmed by 12 lead resting electrocardiography (ECG) (upright P waves in lead II and biphasic in lead V1 before every QRS complex). Patients who had a history of permanent or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF), coronary artery disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or diabetes mellitus (patients with a systolic blood pressure value >140 mm Hg and diastolic blood pressure value >90 mm Hg and glycated hemoglobin >6.4%), pericarditis, valvular heart disease (mitral regurgitation of higher degree than trivial, aortic regurgitation, any degree of valve stenosis, previous valve surgery), pulmonary emboli, cardiomyopathies, pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary artery pressure >25 mm Hg), Grade III and IV diastolic dysfunction, atrioventricular or intraventricular conduction disturbance on the electrocardiogram, abnormal thyroid function, abnormal serum electrolyte values, patients with implanted pacemakers or those receiving antiarrhythmic medications, and poor echocardiographic imaging were also excluded from the study. A written consent was obtained from all patients and our Local Ethical Committee approved the study.

Polysomnography

All participants underwent full-night polysomnography using the compumedics E-series system (Compumedics®, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia). The PSG recordings included 6-channels electroencephalography, 2-channels electrooculography, 2-channels submental electromyography, oxygen saturation by an oximeter finger probe, respiratory movements via chest and abdominal belts, airflow both via nasal pressure sensor and oronasal thermistor, electrocardiography, and leg movements via both tibial anterolateral electrodes. Sleep stages and respiratory parameters were scored according to the standard criteria of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM). Based on the guidelines of the AASM published in 2007, apnea is defined as a ≥90% decrease in airflow persisting for at least 10 s relative to the basal amplitude. Hypopnea is defined as a ≥50% decrease in the airflow amplitude relative to the baseline value with an associated oxygen desaturation or arousal of ≥3%, persisting for at least 10 s. AHI was calculated based on the following formula: total number of obstructive apneas + hypopneas / total sleep time (h).

Echocardiography

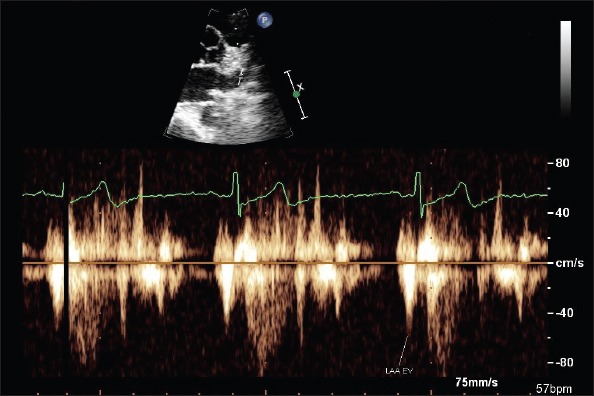

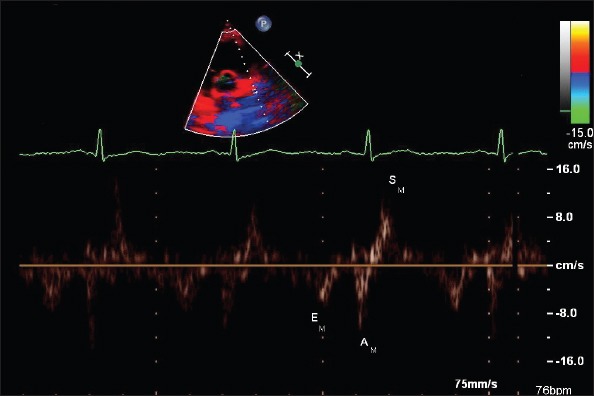

A complete transthoracic echocardiographic evaluation was performed using commercially available ultrasonographic equipment (Phillips ie33 echocardiography system, Phillips Medical System, Bothel, Washington, USA) according to the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography (14). All echocardiographic examinations were recorded and analyzed offline at study completion by an independent experienced cardiologist who was blinded with respect to patients’ clinical characteristics. A 1-lead ECG was recorded continuously. TTE examinations included M-mode, two-dimensional, Doppler flow assessments, and pulsed wave tissue Doppler imaging (PuWa-TDI) measurements (15-17). LV volumes, LV ejection fraction (LVEF), posterior wall (PW), and interventricular septal thickness (IVS) were determined. LA volumes were estimated using the modified Simpson method and indexed to body surface area. LV mass was calculated and indexed to body surface area. LV diastolic performance was evaluated using the pulsed wave Doppler. All Doppler measurements are given as the average values of 10 consecutive cardiac cycles. LV diastolic inflow velocities were obtained from the apical four-chamber view by placing the sample volume at the level of the mitral valve tip. Peak early-diastolic flow velocity (E), peak atrial filling velocity (A), and mitral deceleration time (DT) were measured. PuWa-TDI velocities of longitudinal mitral annular motion were recorded at the septal mitral annular borders. The peak systolic (S’), early diastolic (E’), and late-diastolic (A’) PuWa-TDI velocities over the mitral septal annulus were measured, and the ratio of E/E’ for septal wall was calculated. For the assessment and grading of global LV diastolic function, E/A ratio, DT, and E/E’ ratio was considered (18). LV volumes were calculated at end-systole (largest dimension or end of T wave) and end-diastole (smallest dimension or onset of QRS complex) using the modified Simpson method. Tissue Doppler velocities of the LAA apex and emptying velocities (EV) of LAA were measured on the parasternal short axis. LAA blood velocities were obtained from 63 patients by placing the pulsed Doppler cursor at the proximal third of the LAA cavity after necessary gain and angle adjustments. Biphasic waves subsequent to the ECG-P wave were termed LAA emptying velocity (EV) (Fig. 1). The peak velocity LAA EV was measured and averaged for ten consecutive cardiac cycles. Sample volume was chosen 4 mm. For PuWa-TDI analysis, sample volume was positioned at the apex of the LAA. Care was taken to keep the cursor as parallel as possible to the LAA apex. A triphasic flow pattern was recorded, which included LAA systolic relaxation velocity (SM), LAA early-diastolic velocity (EM), and LAA contraction velocity (AM) (7). The initial early diastolic negative velocity just before the ECG-P wave was termed LAA EM, and the following biphasic negative emptying and positive filling velocities were termed LAA AM and LAA SM, respectively (Fig. 2). The peak velocities of LAA AM, LAA EM, and LAA SM were measured and averaged for 10 consecutive cardiac cycles.

Figure 1.

Left atrial appendage (LAA) pulsed wave Doppler velocities obtained in sinus rhythm from parasternal short axis

EV - LAA emptying velocity

Figure 2.

Left atrial appendage (LAA) tissue Doppler velocities obtained in sinus rhythm from parasternal short axis

EM, LAA - early-diastolic velocity; AM, LAA - contraction velocity; SM, LAA - systolic relaxation velocity

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 16 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). The Shapiro–Wilks normality test was used to determine whether distribution continuous variables have normal distributions. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the Bonferroni test were used to compare groups for continuous variables. Comparison of categorical variables between groups was performed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Correlations between AHI and LAA functions were assessed by using Pearson correlation analysis. Multiple logistic regression analysis was used to determinate risk factors on LAA AM (19). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD), and categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline clinical characteristics of the study population. AHI and body surface area were significantly higher in severe OSA patients than in mild-to-moderate OSA patients and the control group. Mild-to-moderate OSA patients had higher AHI and body surface area values than in the control group (p<0.05). Minimal SaO2 and mean SaO2 values were lower in severe OSA patients compared with those in mild-to-moderate OSA patients and the control group (p<0.05). These values were also lower in mild-to-moderate OSA patients compared with those in the control group (p<0.05). The diagnosis of hypertension was found to be more frequent in severe and mild-to-moderate OSA patients compared with that in the control group (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and sleep characteristics

| Variables | Control group/non-OSA (n=20) | Mild-to-moderate OSA (n=19) | Severe OSA (n=24) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 42.9±13.1 | 41.4±12.6 | 43.1±11.1 | 0.885 |

| Men/women | 12/8 | 12/7 | 13/11 | 0.830 |

| AHI, events/h | 2.7±1.0 | 14.9±8.3a | 60.9±21.3a,b | <0.001 |

| Min SaO2, (%) | 84.9±6.6 | 84.4±5.9 | 75.7±9.7a,b | <0.001 |

| Mean SaO2, (%) | 92.7±2.1 | 92.9±2.0 | 87.9±7.2a,b | 0.004 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 71.4±5.1 | 72.8±5.5 | 69.3±6.6 | 0.151 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 126.7±5.4 | 127.3±6.6 | 129.7±6.0 | 0.195 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 80.7±7.3 | 80.2±5.1 | 78.9±6.5 | 0.633 |

| Diabetes mellitus, (n) | (1) 5% | (1) 5% | (2) 8% | 0.812 |

| Hyperlipidemia, (n) | (9) 45% | (9) 47% | (15) 62% | 0.446 |

| Hypertension, (n) | (5) 25% | (11) 57%a | (15) 62%a | 0.031 |

| Current smoking, (n) | (11) 55% | (10) 52% | (13) 54% | 0.817 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.2±1.0 | 26.4±1.1a | 26.8±1.2 | 0.307 |

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.84±0.10 | 1.83±0.06 | 1.93±0.07a,b | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker, (n) | (1) 5% | (4) 21% | (7) 29% | 0.122 |

| Calcium channel blocker, (n) | (1) 5% | (4) 21% | (5) 20% | 0.273 |

| RAAS blockade, (n) | (4) 20% | (6) 31% | (8) 33% | 0.585 |

AHI - apnea-hypopnea index; OSA - obstructive sleep apnea; RAAS - renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; bpm-beats per minute; mm Hg - millimeters of mercury; kg/m2- kilogram per square meter

vs. control

vs. mild-to-moderate

Left ventricular echocardiography characteristics are shown in Table 2. LV mass index, E mitral deceleration time, E/E’ ratio, LV end-diastolic volume, and LV stroke volume were higher in severe OSA patients compared with those in mild-to-moderate OSA patients and the control group, and E/A ratio and septal E’ were found to be lower, respectively (p<0.05). A velocity and diastolic dysfunction values were higher in severe OSA patients compared with those in the control group, and E velocity and LV ejection fraction were found to be lower, respectively (p<0.05). A velocity, E/E’ ratio, diastolic dysfunction values, LV stroke volume were higher in mild-to-moderate OSA patients compared with those in the control group and E velocity, E/A ratio and septal E’ were found to be lower, respectively (p<0.05).

Table 2.

Comparison of left ventricular echocardiographic characteristics

| Variables | Control group (n=20) | Mild-to-moderate OSA (n=19) | Severe OSA (n=24) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LV mass index (g/m2) | 83.5±4.1 | 83.4±4.4 | 86.6±2.0a,b | 0.006 |

| IVS, mm | 9.5±1.1 | 9.8±1.2 | 10.1±1.1 | >0.05 |

| PW, mm | 8.9±0.9 | 9.1±1.1 | 9.4±1.0 | >0.05 |

| E velocity, cm/s | 94.0±7.6 | 81.1±9.4a | 81.1±9.4a | <0.001 |

| A velocity, cm/s | 61.8±8.5 | 75.4±13.8a | 81.7±19.5a | <0.001 |

| E/A ratio | 1.3±0.1 | 1.1±0.2a | 0.9±0.3a,b | <0.05 |

| E mitral deceleration time, ms | 227.8±18.1 | 234.9±25.2 | 249.8±14.4a,b | 0.001 |

| E/E’ ratio | 7.9±1.0 | 8.9±0.8a | 10.7±1.1a,b | <0.001 |

| Septal E’, cm/s | 11.9±1.5 | 9.1±1.6a | 6.8±1.7a,b | <0.001 |

| Septal A’, cm/s | 8.9±0.9 | 8.4±1.1 | 8.5±1.1 | 0.272 |

| Septal S, cm/s | 8.0±0.8 | 8.1±0.5 | 7.9±0.9 | 0.773 |

| Diastolic dysfunction, (n) | Grade I (5) 25% Grade II (3)15% |

Grade I (8) 42.1%a Grade II (9) 47.4%a |

Grade I (8) 33.3%a Grade II (14)58.3%a |

<0.001 <0.001 |

| LV end-diastolic volume, mL | 88.2±3.3 | 88.5±4.6 | 93.3±5.2a,b | <0.001 |

| LV end-systolic volume, mL | 34.9±1.9 | 35.0±1.7 | 35.9±3.2 | 0.346 |

| LV Stroke volume, mL | 69.6±5.2 | 66.6±4.9a | 62.3±6.6a,b | <0.001 |

| LV ejection fraction,% | 65.5±2.6 | 64.9±2.0 | 63.7±2.5a | <0.042 |

LV - left ventricle; OSA - obstructive sleep apnea; mm - millimeter; cm/s - centimeter per second; Ml - milliliter

vs. control

vs. mild-to-moderate. Oneway ANOVA test

A comparison of left atrial and left atrial appendage echocardiographic characteristics is shown in Table 3. LAA EV, LAA SM, LAA EM, LAA AM, and LA reservoir volume index were lower in severe OSA patients compared with those in mild-to-moderate OSA patients and the control group, and LA minimum volume index was higher, respectively (p<0.05). LAA AM was lower in severe and mild-to-moderate OSA patients compared with that in the control group. LA maximum volume index was higher in severe and mild-to-moderate OSA compared with that in the control group (p<0.05). LA ejection fraction was lower and LA conduit volume index was higher in severe OSA patients compared with those in the control group (p<0.05). LAA SM and LAA EM were lower and LA minimum volume was higher in mild-to-moderate OSA patients than in the control group (p<0.05).

Table 3.

Comparison of left atrial and left atrial appendage echocardiographic characteristics

| Variables | Control Subjects (n=20) | Mild-to-Moderate OSA (n=19) | Severe OSA (n=24) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAA EV, cm/s | 75.2±6.7 | 73.2±9.6 | 63.5±17.1a,b | 0.006 |

| LAA SM, cm/s | 10.0±0.9 | 8.1±1.1a | 6.3±0.9a,b | <0.001 |

| LAA EM, cm/s | 14.0±1.6 | 10.0±2.8a | 6.8±2.2a,b | <0.001 |

| LAA AM, cm/s | 13.6±0.7 | 11.6±0.5a | 11.2±0.3a,b | <0.001 |

| LA maximum volume index, mL/m2 | 38.5±4.0 | 45.3±7.2a | 49.2±9.9a | <0.001 |

| LA minimum volume index, mL/m2 | 18.3±3.9 | 23.5±2.8a | 34.2±7.1a,b | <0.001 |

| LA ejection fraction, % | 47.9±8.9 | 43.1±11.3 | 37.9±11.4a | 0.012 |

| LA conduit volume index, mL/m2 | 51.0±7.2 | 46.4±11.3 | 43.2±9.3a | 0.030 |

| LA reservoir volume index, mL/m2 | 20.2±4.3 | 21.8±8.0 | 15.0±7.0a,b | 0.004 |

EV - emptying velocity; LA - left atrium; LAA - left atrial appendage; OSA - obstructive sleep apnea; cm/s - centimeter per second; mL/m2-milliliter per square meter

vs. control

vs. mild-to-moderate. Oneway ANOVA test

Table 4 shows the correlation of LAA AM with other parameters in the OSA group. LAA AM was negatively correlated with AHI and LV filling pressure and positively correlated with LA conduit volume index (p<0.05).

Table 4.

Correlation of LAA AM with other parameters in the OSA group

| Mild-to-Moderate OSA (n=19) | Severe OSA (n=24) | All OSA Population (n=43) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | r | P | r | P | r | P |

| AHI, events/h | -0.697 | 0.001 | 0.056 | 0.796 | -0.442 | 0.003 |

| Age, years | 0.125 | 0.610 | 0.210 | 0.443 | -0.029 | 0.853 |

| Body-mass index; kg/m2 | -0.225 | 0.354 | 0.107 | 0.620 | -0.126 | 0.419 |

| E/E’ | -0.496 | 0.031 | 0.315 | 0.134 | -0.354 | 0.02 |

| LV mass index, g/m2 | -0.122 | 0.618 | 0.189 | 0.377 | -0.228 | 0.141 |

| LA maximum volume index, mL/m2 | -0.399 | 0.091 | 0.053 | 0.807 | -0.236 | 0.128 |

| LA conduit volume index, mL/m2 | 0.561 | 0.012 | -0.195 | 0.162 | 0.283 | 0.066 |

| LA reservoir volume index, mL/m2 | -0.237 | 0.329 | 0.113 | 0.599 | 0.099 | 0.530 |

| LAA Emptying velocity, cm/s | -0.270 | 0.264 | 0.054 | 0.802 | 0.076 | 0.629 |

| LAA AM | 0.424 | 0.700 | -0.244 | 0.251 | 0.109 | 0.487 |

| LV EF, % | -0.021 | 0.930 | -0.154 | 0.472 | 0.048 | 0.760 |

AHI - apnea-hypopnea index; AM - contraction velocity; LA - left atrium; LAA - left atrial appendage; LV - left ventricle; OSA - obstructive sleep apnea; kg/m2 - kilogram per square meter; mL/m2 - milliliter per square meter; cm/s - centimeter per second. Pearson Correlation Analysis

The multiple predictors for LAA AM were AHI, presence of diastolic dysfunction, and E/E’ values (Table 5).

Table 5.

Results of multiple logistic regression analysis for LAA AM

| 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | OR | Lower | Upper | P |

| AHI, event/h | 1.90 | 1.42 | 2.56 | <0.05 |

| Hypertension | 1.14 | 0.93 | 1.38 | 0.430 |

| Presence of diastolic dysfunction | 1.32 | 1.09 | 1.61 | <0.05 |

| E/E’ | 1.38 | 1.03 | 1.85 | <0.05 |

| LV EF, % | 0.95 | 0.90 | 1.01 | 0.767 |

| LAA AM | 0.85 | 0.67 | 1.08 | 0.314 |

| LA EF, % | 0.86 | 0.69 | 1.06 | 0.350 |

AHI - apnea-hypopnea index; AM - contraction velocity; EF - ejection fraction; LA - left atrium; LV - left ventricle; OSA - obstructive sleep apnea. Multiple logistic regression analysis

Discussion

In the present prospective study it was found that LAA EV and tissue velocities were significantly decreased in patients with OSA and SR compared with those in the control group. The multiple predictors for LAA AM were AHI, presence of diastolic dysfunction, and E/E’ values.

OSA has been found to be an independent risk factor for thromboembolic events in large epidemiological studies (3). More than half of the patients hospitalized with stroke suffer from sleep-disordered breathing, and 5%-10% of patients with newly diagnosed OSA have a history of stroke (20).

Impaired LAA function was associated with long-term cerebrovascular events in patients with a history of stroke and AF (21). The authors hypothesized that vulnerability to systemic thromboembolism could also be caused by depressed LAA function during SR.

Because it is generally difficult to observe the entire LAA by TTE, LAA function has generally been assessed by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). Indeed, TEE LAA AM velocities are lower in patients with AF than in those with SR (22). However, some patients find TEE uncomfortable, and it cannot always be performed in all patients because some refuse to undergo this examination or cannot swallow the TEE probe. Therefore, an alternative method may be required to assess LA or LAA function. Transthoracic tissue Doppler echocardiography could provide a non-invasive physiological analysis of LAA function. In addition, TDI provides a high amplitude signal with a high signal-to-noise ratio, and it is relatively easy to detect signals from the chest wall (5). Thus, this method was chosen to evaluate the LAA parameters in our study. It is well known that TTE LAA AM <13 cm/s closely correlates with spontaneous echo contrast and <11 cm/s with thrombus and consequently with increased embolic risk (5). In a study in non-dipper hypertensive patients, LAA filling and ejection flow rates were found to be decreased relative to dipper hypertensive patients and the control group. This finding suggests that maintenance of LAA function prevents potential complications secondary to LAA dysfunction (23). In another study by Asker et al. (24), patients with untreated systemic hypertension and normal left ventricular systolic function in SR were evaluated at baseline and 6 months after treatment with 5 mg/day ramipril, and a significant increase in LAA filling and emptying velocities after treatment was found. It was concluded that the decrease in blood pressure and hemodynamic improvements as a consequence of ramipril therapy resulted in improved LAA function.

Similar to the abovementioned results, we found that LAA AM values were reduced in patients with OSA and SR in our study. In a multiple logistic regression analysis, LAA AM was predicted by AHI, presence of diastolic dysfunction, and echocardiographic E/E’ value. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating LAA function of OSA patients in SR. There are only limited data about the pathophysiological mechanisms in this regard. Some possible explanations may be as follows: Firstly, there is evidence that recurrent hypoxia can directly reduce myocardial contractility (25). Besides, marked reductions in intrathoracic pressure generated during obstructive events could play a significant role in the development of myocyte slippage and contractile dysfunction in such patients (26). The above observations are validated only for ventricular myocardium. The extent to which these results can be extrapolated on LAA contractility requires further investigation. Secondly, similar to our study, there are sufficient data showing that OSA is often associated with diastolic dysfunction (27, 28). Endothelial dysfunction, surges in blood pressure, hypoxia, and hypercapnia with over activation of sympathetic system, increased preload by intermittent negative intrathoracic pressure, and initiation of the inflammatory system contributes to the development of diastolic function (29). E/E’ value, which is used as an index of left ventricular filling pressures, strongly correlates with LV diastolic dysfunction (30-32). Further, we could show increased parameters for LA volume in OSA patients. This finding suggests that an enlargement of the LA is a morphologic expression of diastolic dysfunction (33). Although admittedly nonspecific, it reflects both the duration and the severity of disease (34). In a recent study, we demonstrated by speckle tracking echocardiography (STE) deformation of LA in OSA patients, which may also be due to diastolic dysfunction (35). Using STE, a further study by Karabay et al. (36) clearly showed that LA deformation parameters predict impaired LAA functions and the presence of LAA thrombus in ischemic stroke patients with suspected cardioembolism; however, it is only applicable to patients with SR.

Study limitations

We assume that the small number of patients may be considered as a limitation. Further studies with larger numbers are required to assess the effects of OSA on LAA parameters in patients with SR. In addition, the possibility that these patients may have intermittent atrial fibrillation cannot be excluded, although no patient had atrial fibrillation at the time of TTE. Finally, it is considered that TEE is a better tool for evaluation of LAA function with a high success rate but with its own limitations. LAA function can be evaluated only in a limited patient group with TTE.

Conclusion

Thromboembolic events are not rare in this patient population although SR is mainly preserved. When the literature is considered as a whole, the evidence suggests that OSA is an independent risk factor for such events. LAA dysfunction during AF and also normal SR may be a crucial pathophysiologic mechanism in this regard. LAA function measured by transthoracic pulsed wave and tissue Doppler echocardiography may become an alternative for routine work-up in OSA patients with SR.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Authorship contributions: Concept - M.G.V., S.Ç.; Design - M.G.V., S.Ç.; Supervision - R.A., H.F.; Resource - R.A., H.F.; Materials - Ö.Ö.A., M.G.V.; Data collection &/or processing - Ö.Ö.A.; Analysis &/or interpretation - M.G.V., S.Ç.; Literature search - H.G., E.Y.; Writing - M.G.V., S.Ç.; Critical review - H.G., E.Y.; Other - E.Y.

References

- 1.Celen YT, Peker Y. Cardiovascular consequences of sleep apnea:I-epidemiology. Anatol J Cardiol. 2010;10:75–80. doi: 10.5152/akd.2010.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, Abraham WT, Costa F, Culebras A, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease:an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:686–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barone DA, Krieger AC. Stroke and obstructive sleep apnea:a review. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15:334. doi: 10.1007/s11883-013-0334-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshida N, Okamoto M, Beppu S. Validation of transthoracic tissue Doppler assessment of left atrial appendage function. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008;20:521–6. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uretsky S, Shah A, Bangalore S, Rosenberg L, Sarji R, Cantales DR, et al. Assessment of left atrial appendage function with transthoracic tissue Doppler echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2009;10:363–71. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jen339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoshida N, Okamoto M, Nanba K, Yoshizumi M. Transthoracic tissue Doppler assessment of left atrial appendage contraction and relaxation:their changes with aging. Echocardiography. 2008;27:839–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2010.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bauer F, Verdonck A, Schuster I, Tron C, Eltchaninoff H, Cribier A, et al. Left atrial appendage function analyzed by tissue Doppler imaging in mitral stenosis:effect of afterload reduction after mitral valve commissurotomy. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:934–9. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hatle L, Sutherland GR. Regional myocardial function-a new approach. Eur Heart J. 2000;21:1337–57. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas L, Levett K, Boyd A, Leung DY, Schiller NB, Ross DL. Changes in regional left atrial function with aging:evaluation by Doppler tissue imaging. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2003;4:92–100. doi: 10.1053/euje.2002.0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoit BD, Shao Y, Gabel M. Influence of acutely altered loading conditions on left atrial appendage flow velocities. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;24:1117–23. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Liming JD, Corbett WS, Nishiyama H, Wexler L, et al. Sleep apnea in 81 ambulatory male patients with stable heart failure:types and their prevalence, consequences, and presentations. Circulation. 1998;97:2154–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.21.2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan J, Sanderson J, Chan W, Lai C, Choy D, Ho A, et al. Prevalence of sleep disordered breathing in diastolic heart failure. Chest. 1997;111:1488–93. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.6.1488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bradley TD, Floras JS. Sleep apnea and heart failure, part I:obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation. 2003;107:1671–8. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000061757.12581.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardin JM, Adams DB, Douglas PS, Feigenbaum H, Forst DH, Fraser AG, et al. American Society of Echocardiography. Recommendations for a standardized report for adult transthoracic echocardiography:a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Nomenclature and Standards Committee and Task Force for a Standardized Echocardiography Report. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:275–90. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.121536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, et al. Chamber Quantification Writing Group;American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee;European Association of Echocardiography. Recommendations for chamber quantification:a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18:1440–63. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinones MA, Otto CM, Stoddard M, Waggoner A, Zoghbi WA. Doppler Quantification Task Force of the Nomenclature and Standards Committee of the American Society of Echocardiography. Recommendations for quantification of Doppler echocardiography:a report from the Doppler Quantification Task Force of the Nomenclature and Standards Committee of the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2002;15:167–84. doi: 10.1067/mje.2002.120202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mor-Avi V, Lang RM, Badano LP, Belohlavek M, Cardim NM, Derumeaux G, et al. Current and Evolving Echocardiographic Techniques for the Quantitative Evaluation of Cardiac Mechanics:ASE/EAE Consensus Statement on Methodology Indications endorsed by the Japanese Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:277–313. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nagueh SF, Appleton CP, Gillebert TC, Marino PN, Oh JK, Smiseth OA, et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2009;22:107–33. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression-Second Edition. USA: John Wiley & Sons, INC; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dumitrascu R, Tiede H, Rosengarten B, Shulz R. Obstructive sleep apnea and stroke. Pneumonologie. 2012;66:476–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agmon Y, Khandheria BK, Gentile F, Seward JB. Echocardiographic assessment of the left atrial appendage. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1867–77. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00472-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wheeler R, Masani ND. The role of echocardiography in the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2011;12:33–8. doi: 10.1093/ejechocard/jer124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumak F, Güngör H. Comparison of the left atrial appendage flow velocities between patients with dipper versus nondipper hypertension. Echocardiography. 2012;29:391–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asker M, Timuçin OB, Asker S, Karadağ MF. Effect of ramipril therapy on abnormal left atrial appendage function. J Int Res. 2011;39:2429–35. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kusuoka H, Weisfeldt ML, Zweier JL, Jacobus WE, Marban E. Mechanism of early contractile failure during hypoxia in intact ferret heart:evidence for modulation of maximal Ca2+-activated force by organic phosphate. Circ Res. 1986;59:270–82. doi: 10.1161/01.res.59.3.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling:concepts and clinical implications:a consensus paper from the international forum on cardiac remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:569–82. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arias MA, Garcia-Rio F, Alonso-Fernandez A, Mediano O, Martinez I, Villamor J. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome affects left ventricular diastolic dysfunction:effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure in men. Circulation. 2005;112:375–83. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.501841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fung JW, Li TS, Choy DK, Yip GW, Ko FW, Sanderson JE, et al. Severe obstructive sleep apnea is associated with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Chest. 2002;121:422–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.2.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carlson JT, Hedner J, Elam M, Ejnell H, Sellgren J, Wallin BG. Augmented resting sympathetic activity in awake patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1993;103:1763–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.6.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee SW, Choi EY, Jung SY, Choi ST, Lee SK, Park YB. E/E'ratio is more sensitive than E/A ratio for detection of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in patients with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:12–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SW, Park MC, Park YB, Lee SK. E/E'ratio is more sensitive than E/A ratio for detection of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2008;17:195–201. doi: 10.1177/0961203307087303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kloch-Badelek M, Kuznetsova T, Sakiewicz W, Tikhonoff V, Ryabikov A, Gonzalez A, et al. European Project on Genes in Hypertension (EPOGH) Investigators. Prevalence of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in European populations based on cross-validated diagnostic thresholds. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2012;10:10. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-10-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsang TS, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, Bailey KR, Seward JB. Left atrial volume as a morphophysiologic expression of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction and relation to cardiovascular risk burden. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:1284–9. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02864-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prittchet AM, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ, Karon BL, Redfield MM. Diastolic dysfunction and left atrial volume:a population-based study. J Am Col Cardiol. 2005;45:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vural MG, Çetin S, Fırat H, Akdemir R, Yeter E. Impact of continuous positive airway pressure therapy on left atrial function in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea:assessment by conventional and two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. Acta Cardiol. 2014;69:175–84. doi: 10.1080/ac.69.2.3017299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karabay CY, Zehir R, Güler A, Oduncu V, Kalaycı A, Aung SM, et al. Left atrial deformation parameters predict left atrial appendage function and thrombus in patients in sinus rhythm with suspected cardioembolic stroke:a speckle tracking and transesophageal echocardiography study. Echocardiography. 2013;30:572–81. doi: 10.1111/echo.12089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]