Abstract

Contact force (CF) monitoring can be useful in accomplishing circumferential pulmonary vein (PV) isolation for atrial fibrillation (AF). This meta-analysis aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of a CF-sensing catheter in treating AF. Randomized controlled trials or non-randomized observational studies comparing AF ablation using CF-sensing or standard non-CF (NCF)-sensing catheters were identified from PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Wanfang Data, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (January 1, 1998–2016). A total of 19 studies were included. The primary efficacy endpoint was AF recurrence within 12 months, which significantly improved using CF-sensing catheters compared with using NCF-sensing catheters [31.1% vs. 40.5%; risk ratio (RR)=0.82; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.73–0.93; p<0.05]. Further, the acute PV reconnection (10.1% vs. 24.2%; RR=0.45; 95% CI, 0.32–0.63; p<0.05) and incidence of major complications (1.8% vs. 3.1%; OR=0.59; 95% CI, 0.37–0.95; p<0.05) significantly improved using CF-sensing catheters compared with using NCF-sensing catheters. Procedure parameters such as procedure duration [mean difference (MD)=-28.35; 95% CI, -39.54 to -17.16; p<0.05], ablation time (MD=-3.8; 95% CI, -6.6 to -1.0; p<0.05), fluoroscopy duration (MD=-8.18; 95% CI, -14.11 to -2.24; p<0.05), and radiation dose (standard MD=-0.75; 95% CI, -1.32 to -0.18; p<0.05] significantly reduced using CF-sensing catheters. CF-sensing catheter ablation of AF can reduce the incidence of major complications and generate better outcomes compared with NCF-sensing catheters during the 12-month follow-up period.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, ablation, contact force-sensing catheter, meta-analysis

Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained arrhythmia, and ablation procedures for AF have been shown to be safe and effective in a large number of cases worldwide (1–4). However, the recurrence rates of AF after catheter ablation are still considerably high (5, 6). Pulmonary vein (PV) reconnection due to ineffective ablation lesions has been identified as the main cause of AF recurrence (7, 8), and catheter–tissue contact is essential for effective ablation lesions (4, 9, 10). However, an accurate measurement of lesions and understanding the limitations of the contact force (CF) are crucial for avoiding complications (11). In recent years, radiofrequency (RF) catheter ablation with CF sensing, a novel method, has been claimed to be potentially responsible for effective ablation. When using it, the catheter–tissue CF can be measured at the catheter tip with fiber optic or magnetic sensors (12).

The safety and effectiveness of CF-sensing catheters have been evaluated in ex vivo models (10, 13) and in vivo experimental studies (14, 15) before their recent application in humans. Experimental data in previous studies have demonstrated a strong relationship between CF and lesion size when using an RF current for catheter ablation (14). However, the efficacy and safety of CF-sensing catheters, particularly for reducing the rate of complications, remain controversial.

The purpose of this meta-analysis was to evaluate the efficacy and safety of catheter AF ablation using CF-sensing catheters.

Methods

Literature search

Electronic databases, such as PubMed, EMBASE, Wanfang Data, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (January 1, 1998–2016), and Cochrane Controlled Trials Register, for reports on all randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or non-randomized observational studies (NROSs) published in English or Chinese were searched using the following medical subject headings, “contact force-sensing catheter,” “ablation,” and “atrial fibrillation,” to capture data on catheter AF ablation using CF-sensing catheters. The abstracts of all identified RCTs or NROSs were independently screened by two reviewers.

Study selection and quality assessment

Studies fulfilling the following criteria were included: (1) patients undergoing AF ablation using CF-sensing catheters and standard non-CF (NCF)-sensing catheters, (2) patients with paroxysmal AF (PAF) or persistent AF (Per AF), and (3) human studies conducted in adults who were 18 years and older. Non-comparative trials, case reports, editorials, and reviews were excluded from this study.

We used PRISMA guidelines in this meta-analysis. Individual studies were checked for the following characteristics: adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment, attrition less than 15%, blinded assessment, intent-to-treat analysis, complete follow-up, and adequate AF monitoring.

Data abstraction

The citations were also reviewed, and data were independently abstracted by two reviewers; disagreements were resolved by discussions. Abstracted data included the following: (1) study type, study size, study design, CF catheter used, mean CF used, and follow-up; (2) age and gender; (3) AF recurrence within 12 months (primary outcomes); (4) occurrence of acute PV reconnection; (5) primary safety endpoint including device-related serious adverse events (events were classified as major and minor complications; major complications included in-hospital death, cardiac perforation, cardiac effusion or tamponade, stroke, PV stenosis, esophageal fistula, severe hemoptysis, phrenic nerve lesion, and thromboembolic event, whereas minor complications were mainly related to vascular access complications, including femoral/subclavian hematoma and arteriovenous fistula); and (6) procedure duration, ablation time, fluoroscopy duration, and radiation dose.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Cochrane RevMan version 5 (The Cochrane Collaboration, UK), and results were expressed as weighted mean differences (MDs) and relative risk for continuous and dichotomous outcomes, respectively, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Outcomes were pooled using the random-effects model when the heterogeneity was moderate or high (I2>50%). However, the fixed-effects model was used when the heterogeneity was low (I2<50%). Radiation doses used among the included studies were compared using a standard MD (SMD) as different radiation units had been used. The present study assessed the heterogeneity between studies using the Cochran’s Q statistic and I2 index. All statistical testing was two tailed with statistical significance at p<0.05.

Results

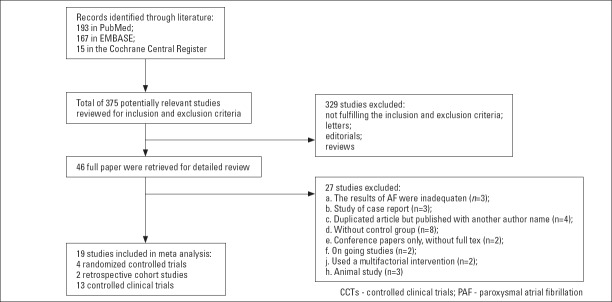

The electronic search identified 193 references from PubMed, 167 from EMBASE, and 15 from the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Among these abstracts, 329 were excluded. The full manuscripts for the remaining 46 studies were retrieved for a detailed review, and 27 were further excluded. Finally, 19 studies (16–34) [4 RCTs (16–19), 2 retrospective cohort studies (20, 21), and 13 NROSs (22–34)] were identified that compared the safety and efficacy of CF-sensing or NCF-sensing catheters in the setting of AF ablation. Information relevant to the literature search is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search stages

Publication bias

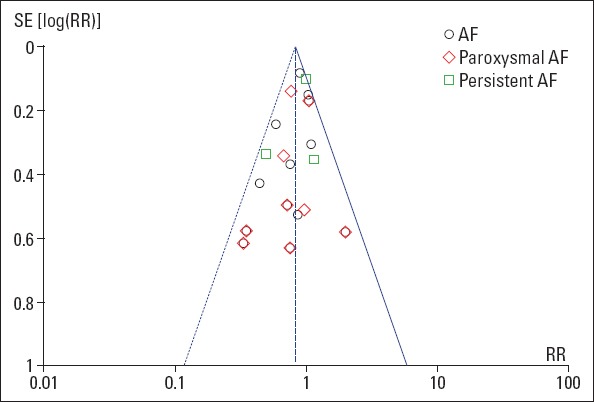

No significant publication bias was found for the primary outcome (AF recurrence at the follow-up) as assessed by a funnel plot (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Funnel plot for the assessment of publication bias for the primary outcome. Effect size is plotted on the x -axis and SE on the y-axis.

AF - atrial fibrillation; RR - risk ratio; SE - standard error

Baseline patient characteristics

Baseline patient characteristics are provided in Table 1. A total of 4053 patients were included in the CF-sensing (n=1546) and NCF-sensing (n=2507) catheter groups.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics and follow-up of the patients

| Type of study | AF (CF/NCF) | PAF (CF/NCF) | PerAF (CF/NCF) | Mean age y(CF/NCF) | Male, n(%) (CF/NCF) | Hypertension n(%) (CF/NCF) | Diabetes, n(%) (CF/NCF) | LA size mm (CF/NCF) | EF (%) (CF/NCF) | CF Catheter | Mean CF, g | Follow up months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reddy 2015 (TOCCASTAR) | prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter study | 295 (152/143) | 295 (152/143) | 0 | 59.6±9.3 /61.0±10.8 | 100 (65.8) /91 (63.6) | 75 (49.3) /69 (48.3) | 16 (10.5) /17 (11.9) | 39.9±5.9 /39.3±4.5 | 62.4±7.1 /62.4±6.2 | TactiCath | NR | 12 |

| Nakamura 2015 | prospective, randomized, controlled study | 120 (60/60) | 80 (38/42) | 40 (22/18) | 64/64.5 | 44 (73.3) /45 (75.0) | 27 (45.0) /36 (60.0) | 8 (13.3) /10 (16.7) | 40±6/39±5 | 67/65 | Thermocool SmartTouch | 18 | 12 |

| Wolf 2015 | Prospective non-randomized study | 36 (24/12) | 27 (18/9) | 9 (6/3) | 58.6±11.3 /62.2±8.5 | 19 (79.2) /11 (91.7) | 8 (33.3) /6 (50.0) | 2 (8.3) /0 (0) | 42.0±3.6 /43.0±4.3 | 56.0±7.9 /58.1±8.0 | Thermocool SmartTouch | 17.8 | NR |

| Itoh 2015 | Prospective non-randomized study | 100 (50/50) | 100 (50/50) | 0 | 65±11 /61±10 | 30 (60) /31 (62) | 32 (64) /26 (52) | 5 (10) /8 (16) | 37±7 /38±6 | 65±10 /65±7 | Thermocool SmartTouch | NR | 12 |

| Makimoto 2015 | Prospective non-randomized study | 70 (35/35) | 44 (19/25) | 26 (16/10) | 67±9 /60±11 | 24 (69) /27 (77) | 25 (71) /29 (83) | 4 (11) /4 (11) | 44±6 /45±6 | 60±7 /60±6 | Thermocool SmartTouch | 16 | 12 |

| Sigmund 2015 | Prospective case- matched control trial | 198 (99/99) | 126 (62/64) | 72 (37/35) | 59.5±9.6 /59.5±9.4 | 71 (72) /68 (69) | 46 (47) /52 (53) | 4 (4) /3 (3) | 40±6 /41±6 | 56±5 /57±7 | Thermocool SmartTouch | NR | 12 |

| G. Lee 2015 | retrospective observational cohort study | 1515 (510/1005) | 656 (238/418) | 750 (255/495) | 60.5±11.0 /60.8±11.3 | 349 (68.4) /264 (63.6) | 77 (15) /140 (14) | 31 (6) /50 (5) | NR | NR | Thermocool SmartTouch | NR | NR |

| Kimura 2014 | prospective, randomized, controlled, study | 38 (19/19) | 28 (15/13) | 10 (4/6) | 62.5±10.1 /57.3±8.6 | 12 (63) /17 (89) | 13 (68.4) /9 (47.4) | 3 (15.8) /4 (21.1) | 41.3±7.8 /42.0±6.8 | 65.7±5.2 /62.4±11.8 | Thermocool SmartTouch | NR | 6 |

| Casella 2014 | prospective, randomized, controlled, study | 55 (20/35) | 55 (20/35) | 0 | 58±10 /56±13 | 16 (80) /28 (80) | 6 (30) /12 (34) | NR | 43.2±6.4 /41.9±5.5 | 62.3±7.4 /62.0±7.8 | Tacticath | 16 | 12 |

| Ullah 2014 | Prospective non-randomized multicenter study | 100 (50/50) | NR | NR | 63/62 | 41 (82) /39 (78) | 11 (22) /7 (14) | 3 (5) /2 (4) | 4.4±0.6 /4.4±0.6 | NR | Thermocool SmartTouch | 13 | 12 |

| Sciarra 2014 | Prospective non-randomized study | 42 (21/21) | 42 (21/21) | 0 | 59.7±9.1 /54.6±11.0 | 18 (86) /18 (86) | NR | 1 (5) /2 (10) | 35±7 /36±6 | 56±5 /55±5 | Thermocool SmartTouch | NR | 2.5 |

| Wakili 2014 | Prospective non-randomized study | 67 (32/35) | 39 (18/21) | 28 (14/14) | 63.6±1.7 /59.3±1.9 | 21 (65.6) /23 (65.7) | 21 (65.6) /25 (71.4) | NR | 43.2±0.9 /42.1±0.9 | 68.5±2.2 /65.0±1.9 | Tacticath | 17.4 | 12 |

| Andrade 2014 | Prospective non-randomized study | 75 (25/50) | 75 (25/50) | 0 | 58.8±12.7 /58.6±11.0 | 19 (76) /43 (86) | NR | NR | 32.4±14.2 /39.2±4.7 | 63.3±5.5 /59.9±5.4 | Thermocool SmartTouch | NR | 13.2±0.9 |

| Wutzler 2014 | Prospective non-randomized study | 143 (31/112) | 104 (19/85) | 39 (12/27) | 59.8±10.9 /60.9±10.2 | 21 (67.7) /71 (63.4) | 20 (64.5) /58 (51.8) | 3 (9.7) /10 (8.9) | 41.5±6.1 /42.4±6.7 | 56.8±4.9 /55.6±3.1 | TactiCath | 26.8 | 12 |

| Marijon 2014 | Prospective non-randomized study | 60 (30/30) | 60 (30/30) | 0 | 59.9±9 /61.0±10 | 21 (70.0) /22 (73.3) | NR | NR | NR | 64.7±4 /65.4±5 | Thermocool SmartTouch | 21.7 | 12 |

| Akca 2014 | Prospective non-randomized study | 449 (143/306) | NR | NR | 55.7±15.1 /51.7±16.6 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Thermocool SmartTouch and Tacticath | NR | NR |

| Jarman 2014 | Retrospective case–control study | 600 (200/400) | 276 (92/184) | 324 (108/216) | 63±12 /61±10 | 149(74.5) /282(70.5) | 80 (40) /119 (30) | 21 (11) /34 (9) | 42±7 /44±7 | NR | Thermocool SmartTouch | NR | 11.4±4.7 |

| Haldar 2012 | Prospective non-randomized study | 40 (20/20) | 14 (7/7) | 26 (13/13) | 63±14 /61±12 | 15 (75) /11 (55) | 7 (35) /6 (30) | NR | 42±8 /41±5 | 57±12 /59±10 | Thermocool SmartTouch | NR | NR |

| Martinek 2012 | Prospective non-randomized study | 50 (25/25) | 50 (25/25) | 0 | 60.5±9.5 /57.4±11.6 | 12 (48) /17 (68) | 10 (40) /12 (48) | 3 (12) /1 (4) | 39±6 /37±6 | 53±4 /53±3 | Thermocool SmartTouch | NR | NR |

| Mean | 18.3 | ||||||||||||

| Total | 4053 (1546/2507) | 2071 (849/1222) | 1324 (487/837) |

AF - atrial fibrillation; CF - contact force; NR - not reported; PAF - paroxysmal atrial fibrillation; Per AF - persistent atrial fibrillation. Statistical analysis was performed using the Cochrane RevMan version 5 software

Ten studies provided detailed information on the PAF and/or Per AF patient subgroups, and relevant information was abstracted to compare the efficacy and safety in the AF, PAF, and/or Per AF subgroups.

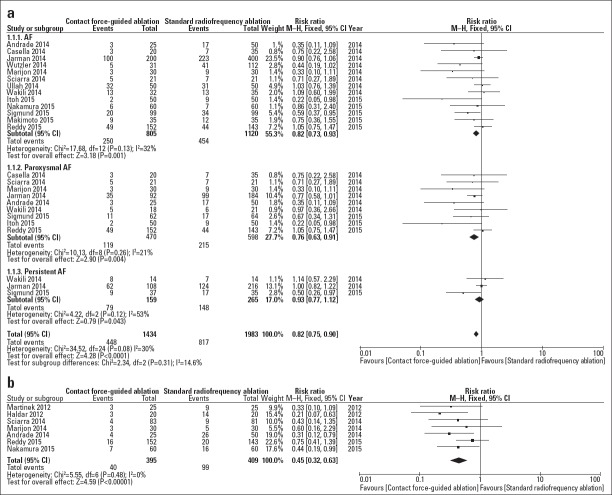

Efficacy of AF ablation using CF-sensing catheters

AF recurrence within 12 months was compared in the AF (13 studies), PAF (9 studies), and Per AF (3 studies) subgroups. In the AF and PAF subgroups, AF recurrence significantly improved using CF-sensing catheters compared with that using NCF-sensing catheters in the AF [31.1% vs. 40.5%; risk ratio (RR)=0.82; 95% CI, 0.73–0.93; I2=32%; p=0.001] and PAF (25.3% vs. 40.0%; RR=0.76; 95% CI, 0.63–0.91; I2=21%; p=0.004) subgroups, which was similar with a previous meta-analysis that included nine studies (35). In the Per AF subgroup, the rate of AF recurrence was numerically lower in the CF group than in the NCF group; however, this did not reach statistical significance (49.7% vs. 55.8%; RR=0.93; 95% CI, 0.77–1.12; I2=53%; p=0.43; Fig. 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Forest plot showing the RR and 95% CI for AF recurrence within 12 months for studies comparing the CF and NCF groups. (b) Forest plot showing the RR and 95% CI for the occurrence of acute PV reconnection for studies comparing the CF and NCF groups

Moreover, seven studies provided data on the rate of acute PV reconnection, and no evidence of heterogeneity was found among the studies (I2=0%). The acute PV reconnection significantly improved using CF-sensing catheters compared with that using NCF-sensing catheters (10.1% vs. 24.2%; RR=0.45; 95% CI, 0.32–0.63; I2=0%; p=0.00001; Fig. 3b).

The CF used in the included studies ranged between 10 and 40 g, and the mean CF used was 18.3 g.

Safety of AF ablation using CF-sensing catheters

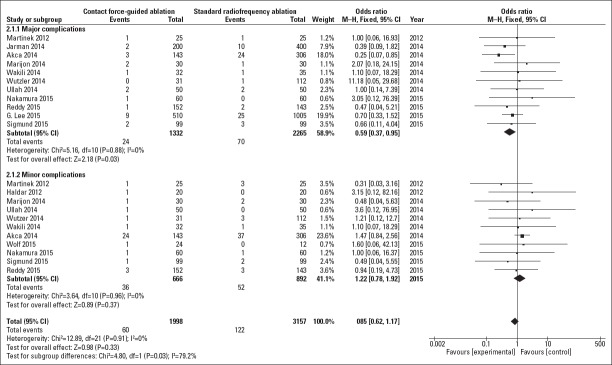

As shown in Figure 4, 11 studies assessed the incidence rate of major complications, and no evidence of heterogeneity was found among these studies (I2=0%). The incidence rate of major complications was significantly lower in the CF group than in the NCF group (1.8% vs. 3.1%; OR=0.59; 95% CI, 0.37–0.95; I2=0%; p=0.03). The incidence rate of minor complications was numerically lower in the CF group than in the NCF group; however, the results did not reach statistical significance (5.4% vs. 5.8%; OR=1.22; 95% CI, 0.78–1.92; I2=0%; p=0.37).

Figure 4.

Forest plot showing odds ratio and 95% CI for the incidence rate of major complications and minor complications for studies comparing the CF and NCF groups

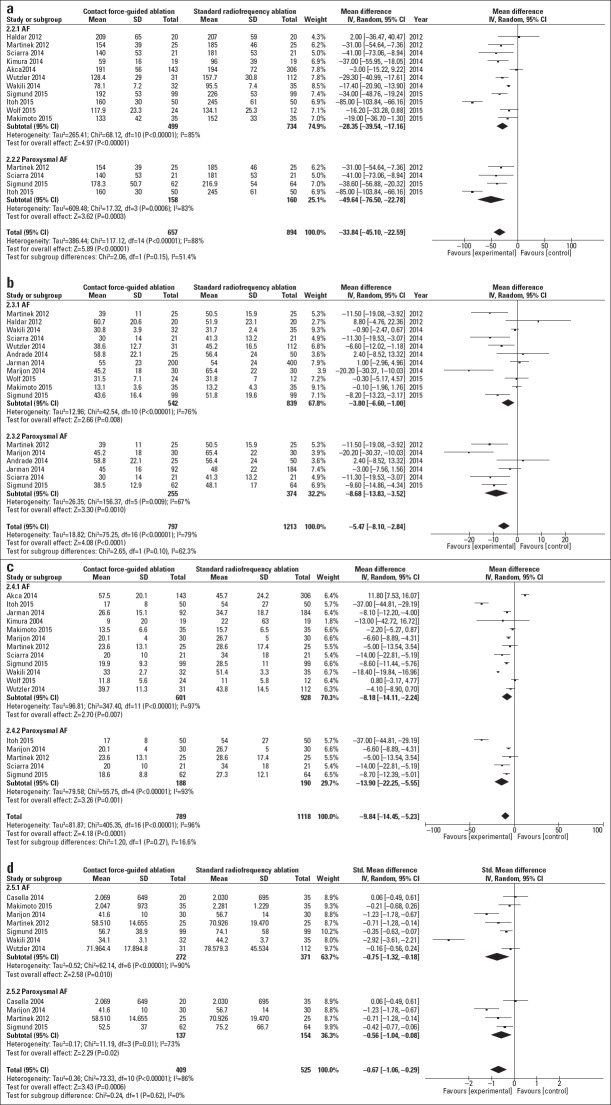

Most included studies provided data on procedure parameters such as procedure duration, ablation time, fluoroscopy duration, and radiation dose in the AF and PAF subgroups. Figure 5 show that in the AF subgroup, the procedure duration [MD=-28.35; 95% CI, -39.54 to -17.16; I2=85%; p=0.00001], ablation time(MD=-3.8; 95% CI, -6.6 to -1.0; I2=76%; p=0.008), fluoroscopy duration (MD=-8.18; 95% CI, -14.11 to -2.24; I2=97%; p=0.007), and radiation dose (SMD=-0.75; 95% CI, -1.32 to -0.18; I2=90%; p=0.01) significantly reduced in the CF-guided group compared with in the NCF group. In the PAF subgroup, the procedure duration (MD=-49.64; 95% CI, -76.5 to -22.78; I2=83%; p=0.0003), ablation time (MD=-8.68; 95% CI, -13.83 to -3.52; I2=67%; p=0.001), fluoroscopy duration (MD=-13.9; 95% CI, -22.25 to -5.55; I2=93%; p=0.0001), and radiation dose (SMD=-0.56; 95% CI, -1.04 to -0.08; I2=73%; p=0.02) significantly reduced in the CF-guided group compared with in the NCF group.

Figure 5.

(a–c) Forest plot showing the unadjusted difference in the mean procedure duration, ablation time, and fluoroscopy duration for studies comparing the CF and NCF groups. (d) Forest plot showing the standard difference in the mean radiation dose for studies comparing the CF and NCF groups

Discussion

This meta-analysis showed that in contrast to AF and PAF ablation performed using NCF-sensing catheters, the use of CF-sensing catheters resulted in a significantly lower rate of acute PV reconnection and AF recurrence during the 12-month follow-up as well as reduced major complications and procedure parameters related to safety.

Achieving a lasting conduction block during the ablation procedure depends on a multitude of factors, including tissue depth, electrode–tissue interface temperature, and electrode tip–tissue contact pressure (29). Insufficient CF during initial lesion formation may result in edema and ineffective non-transmural lesions that allow subacute PV reconnection when the edema resolves (2, 12), whereas excessive contact can cause collateral tissue injury (31, 32, 36). Conventionally, the adequacy of contact between a catheter tip and tissue has been assessed using a combination of subjective factors and objective ablation parameters. Unfortunately, these parameters are poor predictors as they are unreliable and difficult to use (29, 37).

CF-sensing catheters offer a new paradigm in the invasive management of AF. Using these, continuous catheter–tissue CF can be measured, which ensures not only the optimal initial placement of the catheter but also the ability to detect catheter dislodging/sliding in real time (31). According to these features, the use of CF technology resulted in a significant reduction in the rate of acute PV reconnection and AF recurrence after AF ablation compared with the use of NCF.

However, it is a challenge to identify the optimal CF that should be applied during AF ablation to ensure adequate lesion formation, avoiding collateral tissue injury by the mean time.

The TOCCATA study (38) demonstrated that when PV isolation was performed with an average CF of <10 g, AF recurrence was 100%. When the average CF was >20 g, AF recurrence reduced to 20%. A recent published study (39) demonstrated that a CF threshold of >12 g predicts a complete lesion with high specificity. In the TOCCASTAR study, Reddy et al. (16) demonstrated that ablation with an optimal CF (≥90% of lesions created with a CF of ≥10 g) resulted in a significantly higher success rate than that obtained for PV isolation with a non-optimal CF. The EFFICAS II study (40) prospectively applied CF guidelines for ensuring durable isolation of the PV of PAF patients, which demonstrated a target CF of 20 g; a range of 10–30 g resulted in a superior rate of durable PV isolation than the similar protocol without guidelines. The SMART-AF trial, a prospective, multicenter, non-randomized study (41), demonstrated that with an average CF of 17.9±9.4 g, 72.5% of patients were free from AF recurrence in a 12-month follow-up. The current meta-analysis provided important information regarding the use of an optimal average CF of 18.3 g (range, 10–40 g), with acceptable recurrence and complication rates.

Whether the use of CF-sensing catheters can decrease the rate of complications after AF ablation has always been a controversial issue. Akça et al. (32) demonstrated that CF procedures are associated with lesser major complications during AF ablation than NCF ones (2.1% vs. 7.8%, p=0.01). A previous meta-analysis (42) that included 11 studies demonstrated that the major complication rate was numerically lower in the CF group than in the NCF group; however, this did not reach statistical significance (1.3% vs. 1.9%; OR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.29–1.73; p=0.45). With more studies included, the current meta-analysis demonstrated that the incidence of major complications was significantly lower in the CF group than in the NCF group (1.8% vs. 3.1%; OR=0.59; 95% CI, 0.37–0.95; p<0.05).

In the current analysis, the procedure duration, ablation time, fluoroscopy duration, and radiation dose significantly reduced in the CF group compared with in the NCF group in the AF and PAF subgroups. CF-sensing catheters may reduce reliance on fluoroscopy during navigation and the time to achieve intact linear lesions, which promote safety not only for patients but also for operators.

Study limitations

The current analysis had the following limitations: some studies were of limited quality, given their retrospective and single-center designs. Differences in operators’ experience and ablation protocols may have affected the outcomes of the included studies.

Conclusion

AF ablation using CF-sensing catheters has better outcomes than those NCF-sensing catheters during the 12-month follow-up period. Furthermore, the incidence of major complications using CF-sensing catheters was even lower than that using NCF-sensing catheters. The meta-analysis also demonstrated that using an optimal average CF of 18.3 g was associated with higher success and lower complication rates. Randomized controlled studies are required to assess whether catheter ablation using an optimized CF improves the long-term clinical outcome and to determine the exact optimal CF to be used in different patient subgroups.

Acknowledgments:

Thanks to Prof. Duolao Wang for providing evidence-based medicine support.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of the People’s Republic of China (grant no. 81460054) and the Regional Natural Science Foundation of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (grant no. 2016D01C299).

Authorship contributions: Concept – X.Z., B.T.; Design – W.L.; Supervision – X.Z.; Fundings- 2013 33, Hozas, 81460053. Materials – W.L.; Data collection &/or processing – W.Z., Y.L.; Analysis and/or interpretation– Q.Z., Q.X.; Literature search – W.L.; Writing – J.Z., Y.Lu.; Critical review – Medjaden Bioscience Limited; Other – L.Z., Y.Y., H.W., W.Q.

From Biochemist, MD. Meral Eguz’s collections

References

- 1.Camm AJ, Lip GY, De Caterina R, Savelieva I, Atar D, Hohnloser SH, et al. 2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:2719–47. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, Brugada J, Camm AJ, Chen SA, et al. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS Expert Consensus Statement on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design. Europace. 2012;14:528–606. doi: 10.1093/europace/eus027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, et al. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2369–429. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappato R, Calkins H, Chen SA, Davies W, Iesaka Y, Kalman J, et al. Updated worldwide survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety of catheter ablation for human atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:32–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.859116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilber DJ, Pappone C, Neuzil P, De Paola A, Marchlinski F, Natale A, et al. Comparison of antiarrhythmic drug therapy and radiofrequency catheter ablation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:333–40. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verma A, Kılıçaslan F, Pisano E, Marrouche NF, Fanelli R, Brachmann J, et al. Response of atrial fibrillation to pulmonary vein antrum isolation is directly related to resumption and delay of pulmonary vein conduction. Circulation. 2005;112:627–35. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.533190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fürnkranz A, Chun KJ, Nuyens D, Metzner A, Köster I, Schmidt B, et al. Characterization of conduction recovery after pulmonary vein isolation using the “single big cryoballoon” technique. Heart Rhythm. 2010;7:184–90. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2009.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouyang F, Tilz R, Chun J, Schmidt B, Wissner E, Zerm T, et al. Long-term results of catheter ablation in paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: lessons from a 5-year follow-up. Circulation. 2010;122:2368–77. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.946806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes D, Fish JM, Byrd IA, Dando JD, Fowler SJ, Cao H, et al. Contact sensing provides a highly accurate means to titrate radiofrequency ablation lesion depth. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2011;22:684–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2010.01963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thiagalingam AD, D’Avila A, Foley L, Guerrero JL, Lambert H, Leo G, et al. Importance of catheter contact force during irrigated radiofrequency ablation: Evaluation in a porcine ex vivo model using a force - sensing catheter. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2010;21:806–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01693.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi A, Kuwahara T, Takahashi Y. Complications in the catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation incidence and management. Circ J. 2009;73:221–6. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoffmayer KS, Gerstenfeld EP. Contact force-sensing catheters. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2015;30:74–80. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perna F, Heist EK, Danik SB, Barrett CD, Ruskin JN, Mansour M. Assessment of catheter tip contact force resulting in cardiac perforation in swine atria using force sensing technology. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:218–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.959429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokoyama K, Nakagawa H, Shah DC, Lambert H, Leo G, Aeby N, et al. Novel contact force sensor incorporated in irrigated radiofrequency ablation catheter predicts lesion size and incidence of steam pop and thrombus. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:354–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.803650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuck KH, Reddy VY, Schmidt B, Natale A, Neuzil P, Saoudi N, et al. A novel radiofrequency ablation catheter using contact force sensing: Toccata study. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reddy VY, Dukkipati SR, Neuzil P, Natale A, Albenque JP, Kautzner J, et al. Randomized, Controlled Trial of the Safety and Effectiveness of a Contact Force-Sensing Irrigated Catheter for Ablation of Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation: Results of the TactiCath Contact Force Ablation Catheter Study for Atrial Fibrillation (TOCCASTAR) Study. Circulation. 2015;132:907–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura K, Naito S, Sasaki T, Nakano M, Minami K, Nakatani Y, et al. Randomized comparison of contact force-guided versus conventional circumferential pulmonary vein isolation of atrial fibrillation: prevalence, characteristics, and predictors of electrical reconnections and clinical outcomes. J Interv Cardiac Electrophysiol. 2015;44:235–45. doi: 10.1007/s10840-015-0056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kimura M, Sasaki S, Owada S, Horiuchi D, Sasaki K, Itoh T, et al. Comparison of lesion formation between contact force-guided and non-guided circumferential pulmonary vein isolation: a prospective, randomized study. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:984–91. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casella M, Dello Russo A, Russo E, Al-Mohani G, Santangeli P, Riva S, et al. Biomarkers of myocardial injury with different energy sources for atrial fibrillation catheter ablation. Cardiol J. 2014;21:516–23. doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2013.0153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee G, Hunter RJ, Lovell MJ, Finlay M, Ullah W, Baker V, et al. Use of a contact force-sensing ablation catheter with advanced catheter location significantly reduces fluoroscopy time and radiation dose in catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2016;18:211–8. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jarman JW, Panikker S, Das M, Wynn GJ, Ullah W, Kontogeorgis A, et al. Relationship between contact force sensing technology and medium-term outcome of atrial fibrillation ablation: a multicenter study of 600 patients. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2015;26:378–84. doi: 10.1111/jce.12606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf M, Saenen JB, Bories W, Miljoen HP, Nullens S, Vrints CJ, et al. Superior efficacy of pulmonary vein isolation with online contact force measurement persists after the learning period: a prospective case control study. J Interv Card. 2015;43:287–96. doi: 10.1007/s10840-015-0006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itoh T, Kimura M, Tomita H, Sasaki S, Owada S, Horiuchi D, et al. Reduced residual conduction gaps and favourable outcome in contact force-guided circumferential pulmonary vein isolation. Europace. 2016;18:531–7. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makimoto H, Heeger CH, Lin T, Rillig A, Metzner A, Wissner E, et al. Comparison of contact force-guided procedure with non-contact force-guided procedure during left atrial mapping and pulmonary vein isolation: impact of contact force on recurrence of atrial fibrillation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2015;104:861–70. doi: 10.1007/s00392-015-0855-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sigmund E, Puererfellner H, Derndorfer M, Kollias G, Winter S, Aichinger J, et al. Optimizing radiofrequency ablation of paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation by direct catheter force measurement-a case-matched comparison in 198 patients. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2015;38:201–8. doi: 10.1111/pace.12549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ullah W, Hunter RJ, Haldar S, McLean A, Dhinoja M, Sporton S, et al. Comparison of robotic and manual persistent AF ablation using catheter contact force sensing: an international multicenter registry study. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2014;37:1427–35. doi: 10.1111/pace.12501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sciarra L, Golia P, Natalizia A, De Ruvo E, Dottori S, Scara A, et al. Which is the best catheter to perform atrial fibrillation ablation? A comparison between standard ThermoCool, SmartTouch, and Surround Flow catheters. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2014;39:193–200. doi: 10.1007/s10840-014-9874-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wakili R, Clauss S, Schmidt V, Ulbrich M, Hahnefeld A, Schussler F, et al. Impact of real-time contact force and impedance measurement in pulmonary vein isolation procedures for treatment of atrial fibrillation. Clin Res Cardiol. 2014;103:97–106. doi: 10.1007/s00392-013-0625-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrade JG, Pollak SJ, Monir G, Khairy P, Dubuc M, Roy D, et al. Pulmonary vein isolation using “contact force” ablation: The effect on dormant conduction and long-term freedom from recurrent AF: A prospective study. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11:1919–24. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wutzler A, Huemer M, Parwani AS, Blaschke F, Haverkamp W, Boldt LH. Contact force mapping during catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation: procedural data and one-year follow-up. Arch Med Sci. 2014;10:266–72. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2014.42578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marijon E, Fazaa S, Narayanan K, Guy-Moyat B, Bouzeman A, Provi-dencia R, et al. Real-time contact force sensing for pulmonary vein isolation in the setting of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: procedural and 1-year results. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2014;25:130–7. doi: 10.1111/jce.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akca F, Janse P, Theuns DA, Szili-Torok T. A prospective study on safety of catheter ablation procedures: contact force guided ablation could reduce the risk of cardiac perforation. I J Cardiol. 2015;179:441–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.11.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haldar S, Jarman JW, Panikker S, Jones DG, Salukhe T, Gupta D, et al. Contact force sensing technology identifies sites of inadequate contact and reduces acute pulmonary vein reconnection: a pros-pective case control study. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:1160–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martinek M, Lemes C, Sigmund E, Derndorfer M, Aichinger J, Winter S, et al. Clinical impact of an open-irrigated radiofrequency catheter with direct force measurement on atrial fibrillation ablation. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2012;35:1312–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2012.03503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Afzal MR, Chatta J, Samanta A, Waheed S, Mahmoudi M, Vukas R, et al. Use of contact force sensing technology during radiofrequency ablation reduces recurrence of atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1990–6. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yokoyama K, Nakagawa H, Shah DC, Lambert H, Leo G, Aeby N, et al. Novel contact force sensor incorporated in irrigated radiofrequency ablation catheter predicts lesion size and incidence of steam pop and thrombus. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:354–62. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.108.803650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Homoud MK, Mozes A. Physical and experimental aspects of radiofrequency energy, generators, and energy delivery systems. Interventional Cardiac Electrophysiology: A Multidisciplinary Approach. 2015:205. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reddy VY, Shah D, Kautzner J, Schmidt B, Saoudi N, Herrera C, et al. The relationship between contact force and clinical outcome during radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation in the TOCCATA study. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:1789–95. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andreu D, Gomez-Pulido F, Calvo M, Carlosena-Remírez A, Bisbal F, Borràs R, et al. Contact force threshold for permanent lesion formation in atrial fibrillation ablation: A cardiac magnetic resonance–based study to detect ablation gaps. Heart Rhythm. 2016;13:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kautzner J, Neuzil P, Lambert H, Peichl P, Petru J, Cihak R, et al. EFFICAS II: optimization of catheter contact force improves outcome of pulmonary vein isolation for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2015;17:1229–35. doi: 10.1093/europace/euv057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Natale A, Reddy VY, Monir G, Wilber DJ, Lindsay BD, McElderry HT, et al. Paroxysmal AF catheter ablation with a contact force sensing catheter: results of the prospective, multicenter SMART-AF trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:647–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shurrab M, Di Biase L, Briceno DF, Kaoutskaia A, Haj-Yahia S, Newman D, et al. Impact of contact force technology on atrial fibrillation ablation: A Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e002476. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]