Abstract

Impaired neuronal inhibition has long been associated with the increased probability of seizure occurrence and heightened seizure severity. Fast synaptic inhibition in the brain is primarily mediated by the type A γ-aminobutyric acid receptors (GABAARs), ligand-gated ion channels that can mediate Cl− influx resulting in membrane hyperpolarization and the restriction of neuronal firing. In most adult brain neurons, the K+/Cl− co-transporter-2 (KCC2) establishes hyperpolarizing GABAergic inhibition by maintaining low [Cl−]i. In this study, we sought to understand how decreased KCC2 transport function affects seizure event severity. We impaired KCC2 transport in the 0-Mg2+ ACSF and 4-aminopyridine in vitro models of epileptiform activity in acute mouse brain slices. Experiments with the selective KCC2 inhibitor VU0463271 demonstrated that reduced KCC2 transport increased the duration of SLEs, resulting in non-terminating discharges of clonic-like activity. We also investigated slices obtained from the KCC2-Ser940Ala (S940A) point-mutant mouse, which has a mutation at a known functional phosphorylation site causing behavioral and cellular deficits under hyperexcitable conditions. We recorded from the entorhinal cortex of S940A mouse brain slices in both 0-Mg2+ ACSF and 4-aminopyridine, and demonstrated that loss of the S940 residue increased the susceptibility of continuous clonic-like discharges, an in vitro form of status epilepticus. Our experiments revealed KCC2 transport activity is a critical factor in seizure event duration and mechanisms of termination. Our results highlight the need for therapeutic strategies that potentiate KCC2 transport function in order to decrease seizure event severity and prevent the development of status epilepticus.

Keywords: KCC2, Seizure, SLE, Epilepsy, Status epilepticus, Chloride transport, GABA

1. Introduction

The impairment of inhibitory neuronal signaling has long been associated with increased probability and severity of seizures. Fast synaptic inhibition in the brain is primarily mediated by the type A γ-aminobutyric acid receptors (GABAARs), ligand-gated ion channels that mediate Cl− influx to hyperpolarize membranes and restrict neuronal firing. GABAAR mediated inhibition is influenced by the reversal potentials of Cl− and to a lesser extent, (Bormann et al., 1987; Kaila and Volpio, 1987). In most adult brain neurons, the K+/Cl− co-transporter 2 (KCC2) facilitates hyperpolarizing GABAAR currents by maintaining low levels of [Cl−]i (Payne et al., 1996). Consistent with this, KCC2 knockout mice die shortly after birth (Hubner et al., 2005) and KCC2b knockout mice exhibit seizures and death 2–3 weeks postnatally due to profound deficits in inhibitory neurotransmission (Uvarov et al., 2007; Woo et al., 2002). Structurally, KCC2 contains 12 transmembrane domains with intracellular N and C-termini, which are important domains for mediating the cellular regulation of KCC2 (De los Heros et al., 2014). For example, phosphorylation of S940 increased transport activity and stability at the plasma membrane (Lee et al., 2011, 2007) while KCC2-S940A mice show normal basal behavior, but increased severity of kainate induced status epilepticus (Silayeva et al., 2015).

Consistent with its role in supporting inhibitory neurotransmission, deficits in KCC2 activity, including decreased phosphorylation and expression levels, correlate with depolarizing GABAAR currents that have been reported in brain slices from refractory human epileptic patients (Cohen and Navarro, 2002; Huberfeld et al., 2007), and in animal models of temporal lobe epilepsy (De Guzman et al., 2006; Pathak et al., 2007; Barmashenko et al., 2011; Silayeva et al., 2015). Moreover, seizure-related disorders in humans have recently been associated with KCC2 mutations (Kahle et al., 2014; Puskarjov et al., 2014; Stödberg et al., 2015). Deficits in KCC2 expression levels and/or activity also occur in animal models of chronic stress (Hewitt et al., 2009; MacKenzie and Maguire, 2015; Tsukahara et al., 2015, 2016), trauma (Jin et al., 2005), ischemia (Jaenisch et al., 2010), schizophrenia (Hyde et al., 2011) and in peritumoral regions in human brain (Pallud et al., 2014; Semaan et al., 2015). It remains to be determined if deficits in KCC2 activity and expression directly contribute to these varying pathologies. In addition, the significance of KCC2 as a determinant of neuronal Cl− homeostasis has recently been questioned (Glykys et al., 2014).

How do deficits in KCC2 transport activity observed in varying pathologies affect seizure severity? In this study we examined the effects of the selective KCC2 inhibitor VU0463271 (Delpire et al., 2012; Sivakumaran et al., 2015) and the loss of S940 phosphorylation with the KCC2-S940A mutant mouse (Silayeva et al., 2015) on seizure-like events (SLEs) induced by either 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) (Avoli et al., 1996) or 0-Mg2+ conditions (Anderson et al., 1986) in acute slices in vitro. Pharmacological inhibition of KCC2 transport activity by VU0463271 increased the duration of SLEs, rapidly leading to a state of continuous clonic-like discharges in the 0-Mg2+ ACSF model and prolonged SLE duration in the 4-AP model. Likewise, the KCC2-S940A mutation accelerated the appearance of continuous clonic-like discharges in the 0-Mg2+ ACSF model. Our results revealed that KCC2 transport function is a critical determinant of SLE duration and termination in multiple in vitro models.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animal care

All animal studies were performed with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Tufts New England Medical Center.

2.2. Slice preparation

WT C57Bl/6 and KCC2-S940A male mice (age 3–5 weeks) were anaesthetized with isofluorane and brains removed. Horizontal slices (400 mm) containing the hippocampal formation and surrounding cortices were cut on a Leica VT1000s vibratome in cutting solution (in mM): NaCl 126, NaHCO3 26, NaH2PO4 1.25, KCl 2.5, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 0.5, Na-pyruvate 1.5, and glucose 10. Slices were placed in a submerged chamber for a 1 h recovery period at 32 °C in artificial CSF (ACSF) containing (in mM): NaCl 126, NaHCO3 26, KCl 2.5, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 2, glutamine 1, NaH2PO4 1.25, Na-pyruvate 1.5, and glucose 10. All solutions were bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2.

2.3. Field recordings

Slices were transferred to a RC-27L recording chamber (Warner Instruments) and perfused with continually oxygenated ACSF (2–3 mL/min). NaCl (154 mM) filled electrodes (resistance 1–3 mΩ), were placed in the medial entorhinal cortex layer IV. The selective KCC2 inhibitor VU0463271 (Sivakumaran et al., 2015) was dissolved in DMSO before addition to experimental solutions at a final DMSO concentration of 0.001% by volume. This DMSO concentration has previously been shown to have no effect on neuronal activity (Tsvyetlynska et al., 2005). For low-magnesium recordings, ACSF was made without MgCl2 and KCl was brought to 5 mM (0-Mg2+ ACSF). WT slices were incubated in ACSF + VU0463271 (100 nM) for 15 min before changing to 0-Mg2+ ACSF + VU0463271 (100 nM). Slices from the KCC2-S940A mice were recorded in 0-Mg2+ ACSF and compared to WT littermate controls. Further recordings were performed on WT slices using 4-aminopyridine (4-AP, 50 mM), added to the ACSF. To qualitatively compare short duration field events (Fig. 3), recordings were processed using continuous complex wavelet transforms (Morlet wavelet, parameters 1 and 1.5). 540 logarithmically equidistant scales were used between 5 and 50 Hz, and spectra created from modulus of coefficients. Recordings were acquired on a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices) with Clampex 10 software (Molecular Devices). Data were acquired at 10 kHz and analyzed offline with Clampfit (Molecular Devices) and Matlab (Mathworks). Long duration traces (>10 min) were high-pass filtered at 1 Hz for presentation in figures.

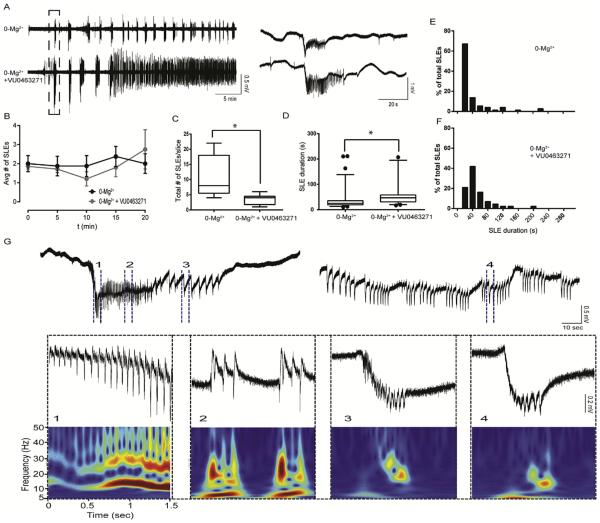

Fig. 3. Reduced KCC2 function by VU0463271 in 0-Mg2+ ACSF increased SLE duration and induced a continuous clonic-like discharge state.

A. Slices incubated in VU0463271 (100 nM, bottom trace) treated with 0-Mg2+ ACSF had several SLEs before transtioning to a continous discharge state, compared with control 0-Mg2+ ACSF slices (top trace), which remained in SLEs with clear periods of post-ictal depression. Traces aligned to the first SLEs. Expansion of first SLEs on right. B. VU0463271 treatment did not alter frequency of SLE occurrence. C.VU0463271 treatment reduced the number of discrete SLEs/slice before transitioning to continous clonic-like discharges. (*p < 0.02) D–F. VU0463271 treatment resulted in longer SLEs (*p < 0.0001). G. Slices treated with VU0463271 transitioned to continous clonic-like discharges. Events expanded with time matched continous wavelet spectra (warmer colors indicate higher power, color scaled between zero and maximum value). Events from the continous clonic state (4) resemble the clonic phase events of the earlier discrete SLE (3).

2.4. Compounds

VU0463271 (Delpire et al., 2012) was synthesized and provided by AstraZeneca.

2.5. Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 6 (GraphPad Software). Statistical significance between two groups was determined using an unpaired Student’s t-test, p < 0.05. For data that was not normal distributed, non-parametric t-tests (Mann Whitney) were performed. Bin width in SLE duration histograms is 20 s. For box-and whisker-plots in Figs. 2–5, box edges are the 25th and 75th percentile, the middle line is the median value, whiskers indicate 95th and 5th percentile, and outer dots indicate outliers. Values in text reported as mean ± SEM.

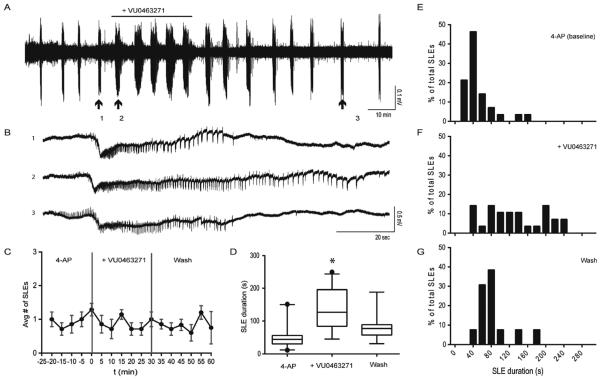

Fig. 2. Reduced KCC2 function by VU0463271 increased the duration of SLEs induced by 4-AP.

A. 4-AP (50 μM) was used to induce SLEs in WT slices. After several SLEs, VU0463271 (100 nM) was applied for 30-min to reduce KCC2 transport function. B. VU0463271 prolonged the duration of SLEs through observable extention of clonic phase (1: Pre- VU0463271, 2: VU0463271, 3: 30-min -post washout VU0463271). C. VU0463271 treatment did not alter frequency of SLE occurrence. (binned in 5 min intervals, vertical lines represent start and end of VU063271 treatment). D–G. VU063271 treatment resulted in longer SLEs that was reversible upon washout. (*p < 0.01).

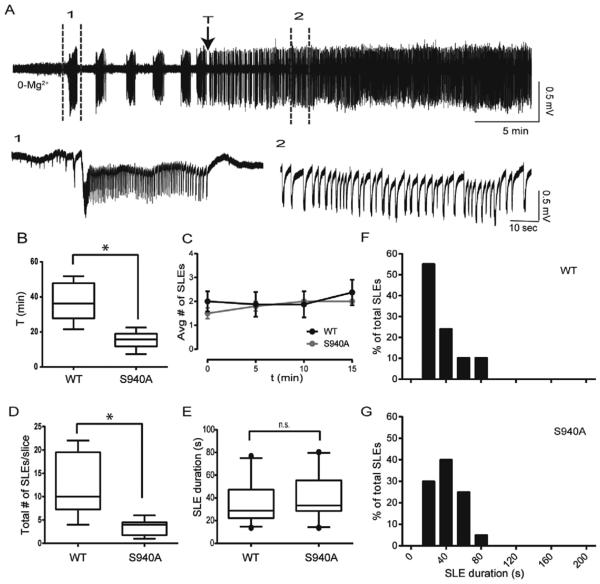

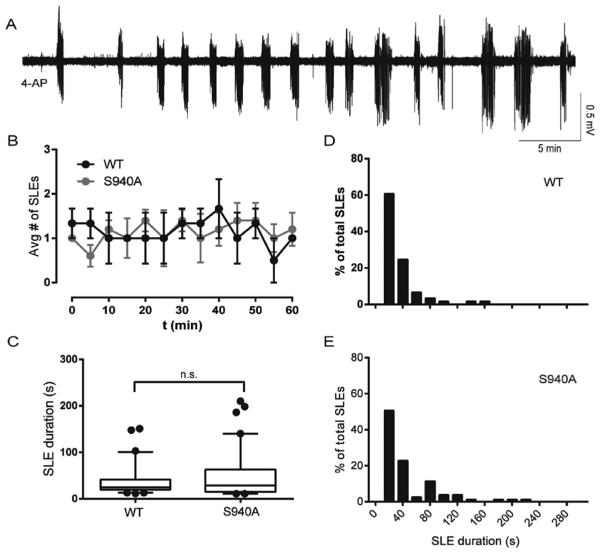

Fig. 5. The KCC2-S940A mutation did not alter initial SLEs induced by 0-Mg2+ ACSF, but enhanced the development of continuous clonic-like discharges.

A. Slices from the KCC2-S940A mouse had several SLEs in 0-Mg2+ ACSF before transitioning to continuous clonic-like activity. (T) points to time of loss of post-ictal depressions of at least 10 s. B. S940A slices showed decreased latency to recurrent discharges, measured from time of 0-Mg2+ ACSF onset. C. There was no difference in frequency of SLE occurrence between the S940A slices and controls in the first 15 min. D. S940A slices displayed a reduced number of discrete SLEs/slice before transitioning to continous clonic-like discharges. (*p < 0.01) E–G. The S940A mutation had no significant effects on SLE duration.

3. Results

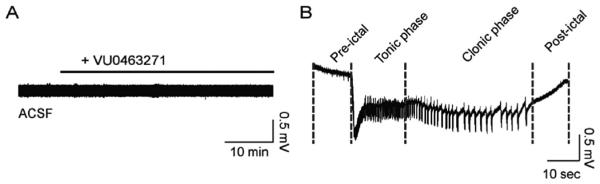

3.1. Inhibition of KCC2 transport by VU0463271 under basal conditions has minimal effects on the development of SLEs

In order to reduce KCC2 transport in vitro we used the KCC2 inhibitor VU0463271, which shows enhanced selectivity over agents such as furosemide (Delpire et al., 2012; Sivakumaran et al., 2015). To initiate our study, we investigated whether inhibiting KCC2 transport activity per se would be sufficient to elicit SLEs. Extracellular field recordings were performed in the medial entorhinal cortex layer IV in ACSF. Treatment of slices for up to 1 h with VU0463271 (100 nM) did not modify significantly LFP activity as measured using field recordings (n = 6; Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Reduced KCC2 transport function by VU0463271 in ACSF was insufficient to elicit SLEs.

A. Slices treated with the KCC2 inhibitor VU0463271 (100 nM) alone in ACSF (2.5 mM Mg2+) did not display field activity typical of in vitro epileptiform events in the entorhinal cortex layer IV. B. A SLE induced by 0-Mg2+ ACSF displaying a characteristic pattern of pre-ictal activity, tonic phase, clonic phase, and post-ictal depression.

3.2. Inhibition of KCC2 transport by VU0463271 increased the duration of SLEs induced by 4-AP

We used 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) to induce SLEs in mouse brain slices containing the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. Application of 4-AP regularly elicits SLEs that originate in the entorhinal cortex (Avoli et al., 1996; Barbarosie and Avoli, 1997) and propagate throughout the temporal lobe. We defined SLEs as events longer than 10 s displaying negative field potential shifts superimposed by tonic-like and clonic-like activity, followed by post-ictal depression (Fig. 1B). We recorded from the medial entorhinal cortex layer IV and only analyzed slices that displayed SLEs (n = 7/10).

After several (4–5) SLEs induced by 4-AP (50 μM), we reduced KCC2 function by applying VU0463271 (100 nM) for 30 min (Fig. 2A, n = 7 slices). We measured the duration and frequency of SLEs before, during, and post VU0463271 treatment (Fig. 2B). VU0463271 treatment resulted in no difference in frequency of SLE occurrence (Fig. 2C). We observed that SLE duration increased during VU0463271 treatment. Baseline SLE duration in 4-AP was 51.2 ± 6.5 s. During the 30 min of VU0463271 treatment, SLEs continued to display tonic-like and clonic-like activity and terminate into post-ictal depression, but were significantly increased in duration (133.0 ± 12.1 s, p < 0.0001), primarily through visible extension of the clonic-like phase of afterdischarges. At 30 min post washout of VU0463271, SLE durations decreased (Fig. 2D–G, 82.4 ± 11.4, p = 0.002 relative to 4-AP baseline). Together these data demonstrated that inhibiting KCC2 transport function by VU0463271 rapidly and reversibly increased the duration of 4-AP induced SLEs.

3.3. Inhibition of KCC2 transport by VU0463271 increased the duration of SLEs induced by 0-Mg2+ ACSF and enhanced the development of continuous clonic-like discharges

In order to further investigate the effects of inhibiting KCC2 transport on SLEs, we used the 0-Mg2+ ACSF model. This preparation results in SLEs in the entorhinal cortex that transition to periods of recurrent discharges at later time points (Anderson et al., 1986; Mody et al., 1987; Dreier and Heinemann, 1991). We assessed the effects of KCC2 inhibition by VU0463271 on the development of SLEs induced by 0-Mg2+ ACSF in the entorhinal cortex. Slices were first pretreated with either vehicle or VU0463271 (100 nM) for 15 min in ACSF, before transitioning to 0-Mg2+ ACSF in the absence or continued presence of VU0463271. Slices were only included in analysis if they displayed 3 or more SLEs after 0-Mg2+ ACSF onset and no spreading depression (VU0463271 group = 8/13 slices, control group = 9/14 slices).

After 0-Mg2+ ACSF onset, control slices remained in SLEs. In contrast, slices incubated in VU0463271 exhibited several discrete SLEs, defined by clear periods of post-ictal depression of at least 10 s, before transitioning to a continuous discharge state within 30 min of first SLE occurrence (Fig. 3A). During a 20 min time window aligned to the first SLE, VU0463271 treatment did not modify frequency of SLE occurrence (Fig. 3B). However VU0463271 treated slices displayed decreased latency from 0-Mg2+ ACSF onset to first SLE (6.8 ± 0.4 min, controls: 11.8 ± 1.7 min, p = 0.028). VU0463271 slices displayed fewer discrete SLEs during first 1 h of recording (Fig. 3C, VU0463271 treated: 3.5 ± 0.7 SLEs/slice, controls: 11.2 ± 2.3 SLEs/slice, p = 0.019), before transitioning to a continuous discharge state. SLEs within the first 30 min were of longer duration in VU0463271 treated slices (65.9 ± 12.7 s) compared with controls (Fig. 2 C–F, 39.4 ± 4.8 s, p < 0.0001).

Continuous clonic-like activity has been described in the entorhinal cortex at later time points in acute slices incubated in 0-Mg2+ ACSF (Dreier and Heinemann, 1991). In VU0463271 treated slices, discrete SLEs transitioned to a continuous discharge state within 30 min of first SLE occurrence. The events in the continuous discharge state showed waveform similarity to events in the cloniclike phase of the initial SLEs, with a negative field potential shift containing several population spikes. We used spectra created by continuous wavelet transform to visualize the respective waveforms to confirm entrance into a continuous clonic-like state (Fig. 3G). This continuous clonic-like state remained stable for several hours until the recording was ended. Our results demonstrated that reduced KCC2 transport function by VU0463271 increased SLE duration in the 0-Mg2+ ACSF model. Furthermore, after several SLEs occurred, reduced KCC2 transport function interfered with SLE termination, resulting in a continuous cloniclike state, reminiscent of status epilepticus.

3.4. The KCC2-S940A mutation did not alter the severity of SLEs induced by 4-AP

KCC2 transport activity and membrane trafficking are potentiated by protein kinase C (PKC)edependent phosphorylation of serine 940 residue (S940) in the C-terminus of the transporter (Lee et al., 2011, 2007). We previously created a mouse where serine 940 has been mutated to an alanine (KCC2-S940A). These mice show no changes in KCC2 levels or basal neuronal Cl− extrusion, but display increased severity of kainate-induced status epilepticus due to activity-dependent loss of KCC2 transport function (Silayeva et al., 2015). In order to further examine the effects of this mutation on recurrent SLEs, we again used the 4-AP model in entorhinalhippocampal slices. We recorded from the medial entorhinal cortex layer IV of KCC2-S940A mouse slices and WT-controls, and we only included in our analysis the slices that displayed SLEs (S940A: 5/7 slices, controls: 3/3 slices).

SLEs induced by 4-AP in the KCC2-S940A mice continued to exhibit tonic-like and clonic-like activity, with periods of post-ictal depression (Fig. 4A). The frequency of SLE occurrence was unaltered, measured through 1 h from the first SLE (Fig. 4B). There was no significant difference in SLE duration between the KCC2-S940A (45.6 ± 4.9 s), and controls (Fig. 4C–E, 35.0 ± 3.6 s, p = 0.868). Thus mutation of S940 does not alter entrance into clonic-like discharges for SLEs induced by 4-AP.

Fig. 4. The KCC2-S940A mutation did not alter SLEs induced by 4-AP.

A. 4-AP (50 μM) was used to induce SLEs in slices from the KCC2-S940A mice (shown) and WT controls. B. There was no difference in SLE occurrence between the S940A slices and controls. C–E. The S940A mutation had no significant effects on the duration of SLEs induced with 4-AP.

3.5. The KCC2-S940A mutation did not alter the duration of SLEs induced by 0-Mg2+ ACSF, but enhanced the development of continuous clonic-like discharges

In order to further investigate if the KCC2-S940A mutation affects SLE parameters, we treated slices from KCC2-S940A and WT control mice with 0-Mg2+ ACSF. Similar to VU0463271 treatment in WT slices, S940A slices displayed several discrete SLEs before transitioning to a continuous clonic-like state within 30 min of first SLE occurrence (Fig. 5A). S940A slices showed decreased latency to the loss of post-ictal depressions of at least 10 s, measured from 0-Mg2+ ACSF onset (Fig. 5B, S940A: 15.4 ± 2.1 min, n = 6 slices, controls: 36.8 ± 3.9 min, n = 8 slices, p = 0.001). Importantly, there was no significant difference in latency from 0-Mg2+ ACSF onset to the first SLE (S940A: 8.9 ± 1.1 min, controls: 11.9 ± 2.0 min, p = 0.237). During a 15 min time window aligned to the first SLE, S940A slices displayed no significant difference in frequency of SLE occurrence (Fig. 5C). S90A slices displayed fewer discrete SLEs during first 1 h of recording (Fig. 5D, S940A: 3.5 ± 0.7 SLEs/slice, controls: 12.1 ± 2.4 SLEs/slice, p = 0.010), before transitioning to a continuous discharge state. SLE duration also was unchanged between the groups (Fig. 5C–E, S940A: 40.5 ± 3.8 s, WT: 34.5 ± 3.3 s, p = 0.119).

Similar to the VU0463271 treated slices, all slices tested from the S940A mice transitioned from a state of discrete SLEs with clear post-ictal depression to continuous clonic-like discharges (Fig. 5A). The continuous clonic-like state in the KCC2-S940A slices remained stable for several hours until the recordings were terminated. Our results demonstrated that the KCC2-S940A mutation alters SLE termination in 0-Mg2+ ACSF, supporting the hypothesis that the S940 residue is an important determinant in limiting the development of clonic-like continuous epileptiform activity.

4. Discussion

In this paper we have used genetic and pharmacological manipulations to assess the role that KCC2 transport plays in limiting seizure severity. We used the KCC2 inhibitor VU0463271, which exhibits higher potency and selectivity compared to the more widely used KCC2 inhibitors such as furosemide and bumetanide (Delpire et al., 2012; Sivakumaran et al., 2015). In addition we performed experiments on brain slices from KCC2-S940A mice that have selective deficits in KCC2 transport during neuronal hyper-excitability (Silayeva et al., 2015). We used multiple in vitro models of epileptiform activity and found that KCC2 plays a critical inhibitory role on seizure-like events.

In our initial experiments, reducing KCC2 transport function by VU0463271 in ACSF (2.5 mM Mg2+) was insufficient to initiate SLEs. This was an expected result since Cl− loading is caused by large increases in Cl− channel activity and GABAergic drive (Thompson and Gahwiler, 1989) which do not occur under basal conditions in the acute slice but do occur in the network during the initial stages of a SLE (Fujiwara-Tsukamoto et al., 2007; Lillis et al., 2012). In agreement with our own results, a recent study showed that Cl− loading of cortical pyramidal neurons by halorhodopsin is insufficient to trigger full SLE activity in vitro, without additional 4-AP treatment (Alfonsa et al., 2015). We therefore used the in vitro models of 0-Mg2+ ACSF or 4-AP to increase the susceptibility of the network to transition to SLEs.

SLEs induced by either 0-Mg2+ ACSF or 4-AP increased in duration in the presence of VU0463271. Network synchrony in the hippocampus becomes highest during the SLE clonic phase (Jiruska et al., 2013), activity dependent upon parvalbumin positive interneurons driving after-discharges through excitatory GABAergic transmission onto pyramidal neurons (Fujiwara-Tsukamoto et al., 2003; 2010, Ellender et al., 2014). Recording in the entorhinal cortex, we observed that after several longer SLEs, clonic-like discharges emerged and remained stable through the entire recording (2–3 h) in slices treated with VU0463271 and 0-Mg2+ ACSF. Reducing KCC2 transport interfered with the SLE termination mechanism. Our results are consistent with theoretical models where elevated neuronal [Cl−]i is predicted to increase seizure duration (Krishnan and Bazhenov, 2011). The clonic state has been previously described in the 0-Mg2+ ACSF model, but only appeared in a fraction of slices tested (Dreier and Heinemann, 1991). However in our experiments, all VU0463271 treated slices that displayed SLEs in 0-Mg2+ ACSF subsequently transitioned to continuous clonic-like discharges. Thus it is likely that the development of the continuous clonic-like state, an in vitro form of severe status epilepticus, is related to deficits in the transport activity of chloride and/or metabolic stability of KCC2. Our results with VU0463271 indicate that the level of KCC2 transport activity is a critical determinant of SLE duration and termination mechanism.

Contrary to our findings, recent work with the 4-AP model described that reduced KCC2 function by VU0240511 is anti-ictogenic in rat entorhinal-hippocampal slices (Hamidi and Avoli, 2015). This result could be due to a mischaracterization of continous epileptiform events, which were described as continuous interictal events without ictal events. Our analysis with VU0463271 on induced SLEs suggests that KCC2 inhibition indeed disrupts ictogenesis, but this is caused by increased duration of clonic-like activity into a non-terminating ictal state resembling severe cases of status epilepticus.

The phosphorylation state of KCC2 is critical in tuning transporter function and therefore GABAergic signaling efficacy (Medina et al., 2014). KCC2-S940 is the only known residue where phosphorylation enhances surface activity (Lee et al., 2007, 2011). Recent genetic studies of patients with idiopathic generalized epilepsy (Puskarjov et al., 2014) identified mutations in KCC2 that decrease KCC2-S940 phosphorylation (Kahle et al., 2014). Decreased KCC2-S940 phosphorylation and increased seizure susceptibility also occur in animal models of chronic stress (MacKenzie and Maguire, 2015; Tsukahara et al., 2016). In our study, we analyzed SLEs induced in slices from KCC2-S940A mice. It is important to note that the genetic manipulation of altered KCC2-S940 phosphorylation is not equivalent to pharmacological inhibition by VU0463271. In 4-AP, KCC2-S940A slices displayed no significant alteration in frequency of SLE occurrence or duration from WT controls. 4-AP rarely elicits continuous clonic-like discharge activity similar to 0-Mg2+ ACSF, unless cation concentrations are altered (Salah and Perkins, 2011). In 0-Mg2+ ACSF, S940A slices showed no difference from controls in frequency of SLE occurrence or SLE duration; however transitioned from discrete SLE events to continuous clonic-like discharges. After several SLEs, S940A slices demonstrated a loss of SLE termination. Our results support the hypothesis that KCC2-S940 phosphorylation has a state-dependent role and is a factor in limiting the onset of continuous clonic discharge activity reminiscent of status epilepticus.

In summary, reducing KCC2 transport function by pharmacological or genetic means altered the severity of induced SLE activity. Impaired KCC2 transport by VU0463271 increased the duration of SLEs in 4-AP and resulted in stable and continous clonic-like discharges in 0-Mg2+ ACSF. Our results with the KCC2-S940A mouse support the critical role played by phosphoregulation of KCC2 function on limiting the onset of in vitro status epilepticus. Decreased KCC2 levels and depolarizing GABAergic activity occur in many neurological disorders linked with increased seizure susceptibility and severity. Our results highlight the need for therapeutic strategies that potentiate KCC2 transport function in order to decrease seizure event severity and prevent the development of status epilepticus.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Simons Foundation Grant 206026 (S.J.M.), National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grants, NS051195, NS056359, NS081735, NS087662 (S.J.M.). The authors would like to thank Dr. Jamie Maguire and members of her laboratory for discussions relevant to this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Alfonsa H, Merricks EM, Codadu NK, Cunningham MO, Deisseroth K, Racca C, Trevelyan AJ. The contribution of raised intraneuronal chloride to epileptic network activity. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:7715–7726. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4105-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson WW, Lewis DV, Swartzwelder HS, Wilson WA. Magnesium-free medium activates seizure-like events in the rat hippocampal slice. Brain Res. 1986;398:215–219. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91274-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avoli M, Barbarosie M, Lucke A, Nagao T, Lopantsev V, Kohling R. Synchronous discharges in the rat limbic potentials and epileptiform system in vitro. J. Neurosci. 1996;76:3912–3924. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-12-03912.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbarosie M, Avoli M. CA3-driven hippocampal-entorhinal loop controls rather than sustains in vitro limbic seizures. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:9308–9314. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09308.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barmashenko G, Hefft S, Aertsen A, Kirschstein T, Köhling R. Positive shifts of the GABAA receptor reversal potential due to altered chloride homeostasis is widespread after status epilepticus. Epilepsia. 2011;52(9):1570–1578. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.03247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bormann J, Hamill OP, Sakmann B. Mechanism of anion permeation through channels gated by glycine and gamma-aminobutyric acid in mouse cultured spinal neurones. J. Physiol. 1987:243–286. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen I, Navarro V. On the origin of interictal activity in human temporal lobe epilepsy in vitro. Science. 2002;298:1418–1422. doi: 10.1126/science.1076510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Guzman P, Inaba Y, Biagini G, Baldelli E, Mollinari C, Merlo D, Avoli M. Subiculum network excitability is increased in a rodent model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Hippocampus. 2006;16:843–860. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De los Heros P, Alessi DR, Gourlay R, Campbell DG, Deak M, Macartney TJ, Kahle KT, Zhang J. The WNK-regulated SPAK/OSR1 kinases directly phosphorylate and inhibit the K+–Cl – co-transporters. Biochem. J. 2014;458:559–573. doi: 10.1042/BJ20131478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delpire E, Baranczak A, Waterson AG, Kim K, Kett N, Morrison RD, Daniels JS, Weaver CD, Lindsley CW. Further optimization of the K-Cl cotransporter KCC2 antagonist ML077: development of a highly selective and more potent in vitro probe. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:4532–4535. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.05.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreier JP, Heinemann U. Regional and time dependent variations of low Mg2+ induced epileptiform activity in rat temporal cortex slices. Exp. Brain Res. 1991;3:581–596. doi: 10.1007/BF00227083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellender TJ, Raimondo JV, Irkle A, Lamsa KP, Akerman CJ. Excitatory effects of parvalbumin-expressing interneurons maintain hippocampal epileptiform activity via synchronous afterdischarges. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:15208–15222. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1747-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara-Tsukamoto Y, Isomura Y, Imanishi M, Fukai T, Takada M. Distinct types of ionic modulation of GABA actions in pyramidal cells and interneurons during electrical induction of hippocampal seizure-like network activity. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;25:2713–2725. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara-Tsukamoto Y, Isomura Y, Imanishi M, Ninomiya T, Tsukada M, Yanagawa Y, Fukai T, Takada M. Prototypic seizure activity driven by mature hippocampal fast-spiking interneurons. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:13679–13689. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1523-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujiwara-Tsukamoto Y, Isomura Y, Nambu a., Takada M. Excitatory gaba input directly drives seizure-like rhythmic synchronization in mature hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells. Neuroscience. 2003;119:265–275. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glykys J, Dzhala V, Egawa K, Balena T, Saponjian Y, Kuchibhotla KV, Bacskai BJ, Kahle KT, Zeuthen T, Staley KJ. Local impermeant anions establish the neuronal chloride concentration. Science. 2014;343:670–675. doi: 10.1126/science.1245423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamidi S, Avoli M. KCC2 function modulates in vitro ictogenesis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt SA, Wamsteeker JI, Kurz EU, Bains JS. Altered chloride homeostasis removes synaptic inhibitory constraint of the stress axis. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:438–443. doi: 10.1038/nn.2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberfeld G, Wittner L, Clemenceau S, Baulac M, Kaila K, Miles R, Rivera C. Perturbed chloride homeostasis and GABAergic signaling in human temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:9866–9873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2761-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubner CA, Stein V, Hermans-borgmeyer I, Meyer T, Ballanyi K, Jentsch TJ. Disruption of KCC2 reveals an essential role of K-Cl cotransport already in early synaptic inhibition. Trends biochem. Sci. 2005;30:i. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00297-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde TM, Lipska BK, Ali T, Mathew SV, Law AJ, Metitiri OE, Straub RE, Ye T, Colantuoni C, Herman MM, Bigelow LB, Weinberger DR, Kleinman JE. Expression of GABA signaling molecules KCC2, NKCC1, and GAD1 in cortical development and schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:11088–11095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1234-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenisch N, Witte OW, Frahm C. Downregulation of potassium chloride cotransporter KCC2 after transient focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2010;41:151–159. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.570424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Impaired Cl− extrusion in layer V pyramidal neurons of chronically injured epileptogenic neocortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;93:2117–2126. doi: 10.1152/jn.00728.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiruska P, de Curtis M, Jefferys JGR, Schevon CA, Schiff SJ, Schindler K. Synchronization and desynchronization in epilepsy: controversies and hypotheses. J. Physiol. 2013;591:787–797. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.239590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahle KT, Merner ND, Friedel P, Silayeva L, Liang B, Khanna A, Shang Y, Lachance-Touchette P, Bourassa C, Levert A, Dion PA, Walcott B, Spiegelman D, Dionne-Laporte A, Hodgkinson A, Awadalla P, Nikbakht H, Majewski J, Cossette P, Deeb TZ, Moss SJ, Medina I, Rouleau GA. Genetically encoded impairment of neuronal KCC2 cotransporter function in human idiopathic generalized epilepsy. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:766–774. doi: 10.15252/embr.201438840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaila K, Volpio J. Postsynaptic fall in intracellular pH induced by GABA-activated bicarbonate conductance. Nature. 1987;330:163–165. doi: 10.1038/330163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan GP, Bazhenov M. Ionic dynamics mediate spontaneous termination of seizures and postictal depression state. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:8870–8882. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6200-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HHC, Deeb TZ, Walker JA, Davies PA, Moss SJ. NMDA receptor activity downregulates KCC2 resulting in depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated currents. Nat. Neurosci. 2011;14:736–743. doi: 10.1038/nn.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HHC, Walker JA, Williams JR, Goodier RJ, Payne JA, Moss SJ. Direct protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation regulates the cell surface stability and activity of the potassium chloride cotransporter KCC2. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:29777–29784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillis KP, Kramer M. a, Mertz J, Staley KJ, White JA. Pyramidal cells accumulate chloride at seizure onset. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012;47:358–366. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie G, Maguire J. Chronic stress shifts the GABA reversal potential in the hippocampus and increases seizure susceptibility. Epilepsy Res. 2015;109:13–27. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina I, Friedel P, Rivera C, Kahle KT, Kourdougli N, Uvarov P, Pellegrino C. Current view on the functional regulation of the neuronal K(+)-Cl(−) cotransporter KCC2. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2014;8:27. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mody I, Lambert DC, Heinemann U. Low extracellular magnesium induces epileptiform activity and spreading depression in rat hippocampal slices. J. Neurophys. 1987;57(3):869–888. doi: 10.1152/jn.1987.57.3.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallud J, Le Van Quyen M, Bielle F, Pellegrino C, Varlet P, Labussiere M, Cresto N, Dieme M-J, Baulac M, Duyckaerts C, Kourdougli N, Chazal G, Devaux B, Rivera C, Miles R, Capelle L, Huberfeld G. Cortical GABAergic excitation contributes to epileptic activities around human glioma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014;6:244ra89–244ra89. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak HR, Weissinger F, Terunuma M, Carlson GC, Hsu F-C, Moss SJ, Coulter DA. Disrupted dentate granule cell chloride regulation enhances synaptic excitability during development of temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:14012–14022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4390-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne JA, Stevenson TJ, Donaldson LF. Molecular characterization of a putative K-Cl cotransporter in rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:16245–16252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puskarjov M, Seja P, Heron S. A variant of KCC2 from patients with febrile seizures impairs neuronal Cl− extrusion and dendritic spine formation. EMBO Rep. 2014;15:723–729. doi: 10.1002/embr.201438749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salah A, Perkins KL. Persistent ictal-like activity in rat entorhinal/perirhinal cortex following washout of 4-aminopyridine. Epilepsy Res. 2011;94:163–176. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.01.017. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2011.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semaan S, Wu J, Gan Y, Jin Y, Li G-H, Kerrigan JF, Chang Y-C, Huang Y. Hyperactivation of BDNF-TrkB signaling cascades in human hypothalamic hamartoma (HH): a potential mechanism contributing to epileptogenesis. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2015;21:164–172. doi: 10.1111/cns.12331. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cns.12331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silayeva L, Deeb TZ, Hines RM, Kelley MR, Munoz MB, Lee HHC, Brandon NJ, Dunlop J, Maguire J, Davies PA, Moss SJ. KCC2 activity is critical in limiting the onset and severity of status epilepticus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2015;112:3523–3528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415126112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumaran S, Cardarelli R, Maguire J, Kelley MR, Silayeva L, Morrow DH, Mukherjee J, Moore YE, Mather RJ, Duggan ME, Brandon NJ, Dunlop J, Moss SJ, Deeb TZ. Selective inhibition of KCC2 leads to hyperexcitability and epileptiform discharges in hippocampal slices and in vivo. J. Neurosci. 2015;35:8291–8296. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5205-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stödberg T, McTague A, Ruiz AJ, Hirata H, Zhen J, Long P, Farabella I, Meyer E, Kawahara A, Vassallo G, Stivaros SM, Bjursell MK, Stranneheim H, Tigerschiöld S, Persson B, Bangash I, Das K, Hughes D, Lesko N, Lundeberg J, Scott RC, Poduri A, Scheffer IE, Smith H, Gissen P, Schorge S, Reith MEA, Topf M, Kullmann DM, Harvey RJ, Wedell A, Kurian MA. Mutations in SLC12A5 in epilepsy of infancy with migrating focal seizures. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8038. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S, Gahwiler B. Activity-dependent disinhibition. I. Repetitive stimulation reduces IPSP driving force and conductance in the hippocampus in vitro. J. Neurophysiol. 1989;61:501–511. doi: 10.1152/jn.1989.61.3.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukahara T, Masuhara M, Iwai H, Sonomura T, Sato T. Repeated stress-induced expression pattern alterations of the hippocampal chloride transporters KCC2 and NKCC1 associated with behavioral abnormalities in female mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;465(1):145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.07.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukahara T, Masuhara M, Iwai H, Sonomura T, Sato T. The effect of repeated stress on KCC2 and NKCC1 immunoreactivity in the hippocampus of female mice. Data Brief. 2016;6:521–525. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2015.12.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsvyetlynska NA, Hill RH, Grillner S. Role of AMPA receptor desensitization and the side effects of a DMSO vehicle on reticulospinal EPSPs and locomotor activity. J. Neurophysiol. 2005;94:3951–3960. doi: 10.1152/jn.00201.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uvarov P, Ludwig A, Markkanen M, Pruunsild P, Kaila K, Delpire E, Timmusk T, Rivera C, Airaksinen MS. A Novel N-terminal isoform of the neuron-specific K-Cl Cotransporter KCC2. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:30570–30576. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705095200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo N-S, Lu J, England R, McClellan R, Dufour S, Mount DB, Deutch AY, Lovinger DM, Delpire E. Hyperexcitability and epilepsy associated with disruption of the mouse neuronal-specific K-Cl cotransporter gene. Hippocampus. 2002;12:258–268. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]