Abstract

This study provides national prevalence estimates of US military Veterans with severe pain, and compares Veterans to nonveterans of similar age and sex. Data used are from the 2010–2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) on 67,696 adults who completed the Adult Functioning and Disability (AFD) Supplement. Participants with severe pain were identified using a validated pain severity coding system imbedded in the NHIS AFD. It was estimated that 65.5% of US military Veterans reported pain in the previous 3 months, with 9.1% classified as having severe pain. In comparison to Veterans, fewer nonveterans reported any pain (56.4%) or severe pain (6.4%). While Veterans aged 18–39 had significantly higher prevalence rates for severe pain (7.8%) than did similar-aged nonveterans (3.2%), Veterans age 70 or older were less likely to report severe pain (7.1%) than nonveterans (9.6%). Male Veterans (9.0%) were more likely to report severe pain than male nonveterans (4.7%); however, no statistically significant difference was seen between the two female groups. The prevalence of severe pain was significantly higher in Veterans with back pain (21.6%), jaw pain (37.5%), severe headaches or migraine (26.4%), and neck pain (27.7%) than in nonveterans with these conditions (respectively: 16.7%; 22.9%; 15.9%; and 21.4%). Although Veterans (43.6%) were more likely than nonveterans (31.5%) to have joint pain, no difference was seen in the prevalence of severe pain associated with this condition.

Perspective

Prevalence of severe pain, defined as that which occurs “most days” or “every day” and bothers the individual “a lot”, is strikingly more common in Veterans than in members of the general population, particularly in Veterans who served during recent conflicts. Additional assistance may be necessary to help Veterans cope with their pain.

Keywords: Veterans, pain severity, back pain, joint pain, migraine

INTRODUCTION

Military Veterans make up approximately 9–10% of the US adult population, 46 and are unique in many ways. At the time of entering into military service, Veterans are generally healthier than the typical US adult of similar age because of the rigorous physical and mental screening requirements to join the military. Active duty military are required to maintain specified physical requirements throughout their service and have access to comprehensive medical care, including preventive care. However, during service they are at risk for both combat-related and unrelated physical injuries, and are often exposed to both environmental and mental stressors. Thus, research has shown that military Veterans have poorer overall health-related quality-of-life than nonveterans.13,18,23,25 Veterans are also more likely than age-matched nonveterans to have psychological distress and chronic health conditions (e.g., asthma, cancer, diabetes, emphysema, hypertension, heart disease, kidney disease).23

A number of reports have documented high prevalence of pain-related conditions in Veterans including abdominal pain,20,43,44 arthritis,8,10,12,18,22,30 back pain,5,16,20–22 fibromyalgia,10 headache,31,44 and joint pain7,16,20,21,31,43,44 especially among the Veterans of recent military conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Veterans also score poorly on the SF-36 bodily pain scale17,21,22,40 and frequently report that their pain interferes with usual activities.4,6

Several studies have directly compared pain in military Veterans to nonveterans using nationally representative data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).4,8,18,30 Three studies using the BRFSS examined the prevalence of arthritis in different years. 8,18,30 All three studies found higher prevalence of arthritis in Veterans (range: 31.5%–51.5%) than nonveterans (range: 21.5%–25.6%). A fourth BRFSS study4 found higher prevalence of pain within the past 30 days among male Veterans (6.9%) than male nonveterans (3.6%).

Although this literature identifies the prevalence of pain-related health conditions among Veterans, to our knowledge no previous study has examined the severity of pain in a nationally representative population of Veterans, or examined the association of pain severity with specific pain-related conditions (i.e., back pain, jaw pain, joint pain, neck pain, and severe headaches or migraine). The specific objectives of this study were, therefore, to: 1) compare the 3-month prevalence of both any pain and severe pain between Veterans and nonveterans; 2) examine the relationship of age and sex with pain prevalence and severity in Veterans and nonveterans; and 3) compare the prevalence of severe pain associated with specific pain-related conditions in Veterans and nonveterans. Results from this study may help guide practitioners caring for Veterans and may be of value in future iterations of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pain Management Strategy.47

METHODS

Population

The data used in this report are from the 2010–2014 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) Sample Adult Core and the NHIS Adult Functioning and Disability Supplement (AFD).34 The NHIS is an in-person annual survey of the health of the US civilian, noninstitutionalized population conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The NHIS collects health and sociodemographic information on each member of all families residing within a sampled household. Within each family, additional information is collected from one randomly selected adult (the “sample adult”) aged 18 years or older. The survey uses a multi-stage clustered sample design and oversamples black, Asian, and Hispanic populations. When combined with NCHS-derived sampling weights, this design allows accurate extrapolation of findings to the civilian, noninstitutionalized US adult population. Five years of data were combined to increase the reliability of estimates for some of the smaller population subgroups.

Combining the years 2010–2014, NHIS interviews were completed in 202,091 households and 206,936 families, with 165,950 adults aged 18 years and over completing the Sample Adult questionnaire. The final response rate (which takes into account household and family nonresponse) for the 2010–2014 combined Sample Adult files was 61.6%, and the household response rate for the combined years was 77.4%. Approximately one-quarter of sampled adults were randomly chosen to participate in the AFD supplement. Almost all (67,725) completed the supplement, resulting in a 97% supplement response rate. Given this high rate, no attempt was made to impute missing data.

Years 2010–2014 of the NHIS were approved by the NCHS Research Ethics Review Board. Verbal consent was obtained from all survey respondents.

Dependent Variable: Assessment of Pain

The AFD collected information on the persistence and bothersomeness (intensity) of self-reported pain in the previous 3 months. The Washington Group on Disability Statistics (WGDS), constituted by the United Nations Statistical Commission, developed and validated these questions through cognitive testing and pilot surveys in the United States and internationally.26–28,47 Respondents were first asked how often they had pain in the previous 3 months: never, some days, most days, or every day. For those who had pain on at least some days, a follow-up question assessing bothersomeness was asked: “Thinking about the last time you had pain, how much pain did you have—a little, between a little and a lot, or a lot.”

For individuals reporting pain at least some days, Miller and Loeb,28 working with the WGDS, have suggested a coding scheme that combines persistence and bothersomeness of pain to create four discrete categories of increasingly severe pain.9,28 In this scheme, the severe pain is defined as that which occurs “most days” or “every day” and bothers the individual “a lot.” This scheme was tested and validated in a number of countries using a variety of qualitative and mixed-method assessments.9, 26–28,48 The scheme has been quantitatively verified using NHIS data,33 shown to have concurrent validity,32 and used to produce population estimates of pain in the United States.32

Independent Variable

The NHIS defines veteran status using two questions. The first asks: “Are you currently in the armed forces?” Individuals responding “yes” are coded as active military and, by NHIS design, are excluded from further questions. Individuals responding “no” are then asked: “Have you ever served on active duty in the US Armed Forces, Military Reserves, or National Guard?” Individuals responding “yes” are coded as Veterans, while those responding “no” are coded as nonveterans.

Age and Sex

Pain prevalence and severity were examined by age and sex. These demographic characteristics have previously been shown to be associated with both pain prevalence19,37–39 and pain severity.32 For analytic purposes, participant age was coded as 18–39, 40–49, 50–59, 60–69, and 70 years of age and older.

Painful Health Conditions

The 2010–2014 NHIS Adult Core questionnaires included questions on the presence of arthritis, any back pain, back pain without sciatica (BP w/o sciatica), back pain with sciatica (BP+sciatica), jaw pain, joint pain, neck pain, and severe headache or migraine (henceforth referred to as migraine).

Statistical Analyses

Contingency tables were used to assess the relationships between the ordinal pain categories and all other variables. Global associations between the prevalence of severe pain and categorical variables were assessed using the chi-square test. The Z-test was used to compare individual prevalence rates between Veterans and nonveterans. Multiple logistic regression was used to assess the relationship between severe pain and veteran status. Interactions between veteran status and age or sex were examined in the regression model. Additional covariates in the model included race (white, black, Asian, other), Hispanic ethnicity (yes, no), educational attainment (less than high school, high school or equivalent, some college, bachelor’s degree or higher) and survey year. We used the SUDAAN EXP option to make the following pair-wise comparisons of odds ratios: 1) Veterans versus nonveterans, aged 18–39; 2) Veterans versus nonveterans aged 40–49; 3) Veterans versus nonveterans aged 50–59; 4) Veterans versus nonveterans aged 60–69; 5) Veterans versus nonveterans aged 70 or more. Because of the enhanced statistical power generated by the large sample size, alpha was set at 0.01 and more conservative 99% confidence intervals were used in the regression analyses. For the multiple logistic regression, there was no evidence of collinearity in inspections of tolerance values, condition indices, and variance inflation factors, suggesting properly specified heteroskedastic models. All estimates were generated using SUDAAN software (version 9.0, Research Triangle Institute, Inc., Research Triangle Park, NC). For inferences about the US population, we used the NCHS sampling weights assigned to the AFD.

RESULTS

Of the five-year NHIS AFD sample, 9.7% (standard error [SE] 0.16) were identified as US military Veterans. Veterans were older than nonveterans and more likely to be male (Table 1). Veterans were also more likely to report having any pain in the prior 3 months than nonveterans (65.6% [SE 0.8] versus 56.4% [SE 0.3]; P<.001) and to report severe pain (9.1% [SE 0.5] versus 6.4% [SE 0.1]; P<.001).

Table 1.

Study Population Characteristics.

| Veterans | Nonveterans | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Population | Sample Population | ||||||||||||

| n | weighted N (thousands) | weighted % | SEa | % reporting pain | SEa | n | weighted N (thousands) | weighted % | SE | % reporting pain | SE | ||

| Total | 6,647 | 22,718 | 100 | 65.6 | 0.8 | 61,049 | 211,763 | 100.00 | 56.4 | 0.3 | |||

| Age | 18–39 | 754 | 2,752 | 12.1 | 0.6 | 56.5 | 2.4 | 23,463 | 87,313 | 41.2 | 0.4 | 46.5 | 0.5 |

| 40–49 | 757 | 3,054 | 13.4 | 0.6 | 62.1 | 2.3 | 10,549 | 39,210 | 18.6 | 0.2 | 57.6 | 0.6 | |

| 50–59 | 1,095 | 4,060 | 17.9 | 0.8 | 69.8 | 2.2 | 10,634 | 38,026 | 18.0 | 0.2 | 64.1 | 0.7 | |

| 60–69 | 1,804 | 5,962 | 26.2 | 0.7 | 67.8 | 1.5 | 8,412 | 26,028 | 12.3 | 0.2 | 66.8 | 0.8 | |

| 70+ | 2,237 | 3,896 | 30.3 | 0.7 | 66.7 | 1.3 | 7,991 | 21,086 | 10.0 | 1.8 | 69.4 | 0.7 | |

| Sex | Male | 6,091 | 21,024 | 92.5 | 0.4 | 65.3 | 0.8 | 24,084 | 92,102 | 43.5 | 0.3 | 51.8 | 0.5 |

| Female | 556 | 1,694 | 7.5 | 0.4 | 70.1 | 2.8 | 36,965 | 119,662 | 56.5 | 0.3 | 60.0 | 0.4 | |

Footnotes:

Standard error

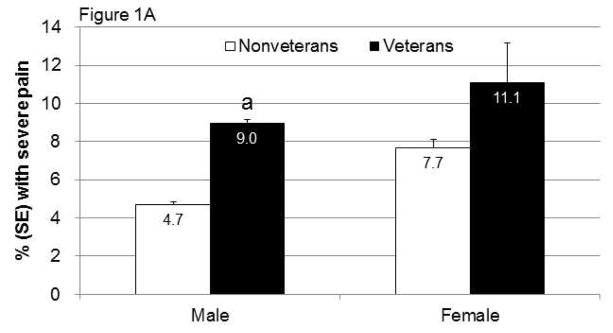

Male Veterans were more likely to report any pain (Table 1) than male nonveterans (65.3% [SE 0.8] versus 51.8% [SE 0.5]; P<.001) and also to have higher rates of severe pain (Figure 1A: 9.0% [SE 0.5] versus 4.7% [SE 0.2]; P<.001). Although female Veterans were more likely to report any pain than female nonveterans (Table 2: 70.1% [SE 2.8] versus 60.0% [SE 0.4]; P<.001), no difference was seen in the proportion with severe pain (Figure 1A: 11.1% [SE 2.1] versus 7.7% [SE 0.2]; P=.11).

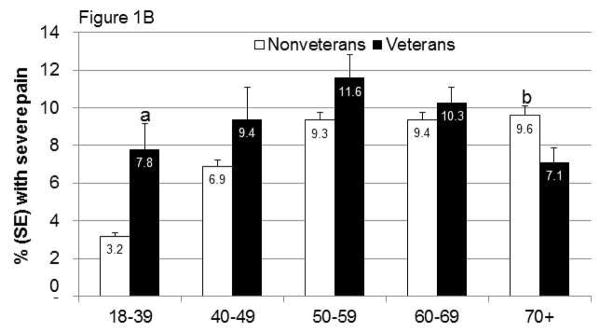

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Severe Pain in Veterans and Nonveterans by Sex (A) and Age (B). Footnotes: SE: Standard error. aP<.001 bP=.008

Table 2.

Associations of veteran status, age, and sex with severe pain

| Variable | Adjusteda Odds Ratio (99% CIb) |

|---|---|

| Veteranc | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) |

| Femaled | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) |

| Age rangee | |

| 18–30 | 0.3 (0.3, 0.4) |

| 40–49 | 0.7 (0.6, 0.9) |

| 50–59 | Ref |

| 60–69 | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) |

| 70 or more | 0.8 (0.6, 0.9) |

| Veteran status x Age | |

| Veteran, aged 18–39f | 3.1 (1.8, 5.2) |

| Veteran, aged 40–49g | 1.6 (1.0, 2.9) |

| Veteran, aged 50–59h | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) |

| Veteran, aged 60–69i | 1.5 (1.1, 2.0) |

| Veteran, aged 70 or morej | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) |

Footnotes:

The multivariable logistic regression model included veteran status, sex, age, race, Hispanic ethnicity, educational attainment, and survey year. The model also contained an interaction term for veteran status and age.

Confidence Interval

Referent: Nonveterans

Referent: Males

Referent: 18–39 years of age

Referent: Nonveterans, aged 18–39

Referent: Nonveterans, aged 40–49

Referent: Nonveterans, aged 50–59

Referent: Nonveterans, aged 60–69

Referent: Nonveterans, aged 70 or more

Veterans aged 18–39 (Table 1: 56.5% [SE 2.4]) were more likely to report any pain than nonveterans of the same ages (46.5% [SE 0.5], P<.001). Veterans aged 18–39 were also more likely to report severe pain than similarly aged nonveterans (Figure 1B: 7.8% [SE 1.4] versus 3.2% [0.2]; P=.001). Veterans aged 70 or older were less likely to report severe pain than similarly aged nonveterans (7.1% [SE 0.8] versus 9.6% [SE 0.5]; P=.008). No other age-specific differences were seen between Veterans and nonveterans.

After controlling for age, sex, race, ethnicity, education and survey year in the logistic regression analysis, Veterans had 1.5 times the odds (99% confidence interval (CI) [1.1, 2.0]) of having severe pain than nonveterans (Table 2). The regression revealed an interaction between age and veteran status (P<.001) but not between sex and veteran status (P=.34). Veterans aged 18–39 had 3.1 times the odds (99% CI [1.8, 5.2]) of having severe pain as same-aged nonveterans. No difference was seen between Veterans and nonveterans aged 70 or more. For other age groups, Veterans were about 1.5 times more likely to have severe pain than nonveterans (Table 2). In the regression model, women were more likely than men to have severe pain (OR 1.5, 99%CI [1.3, 1.7]).

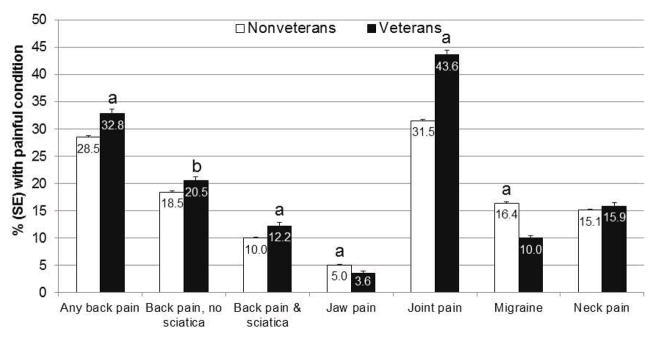

Figure 2 compares the prevalence of selected pain-related conditions in Veterans and nonveterans. Veterans had significantly higher prevalence rates than nonveterans for any back pain (32.8% [SE 0.8] versus 28.5% [0.3]; P<.001), BP w/o sciatica (20.5% [SE 0.7] versus 18.5% [SE 0.2]; P=.006), BP+sciatica (12.2% [SE 0.6] versus 10.0% [SE 0.2]; P<.001), and joint pain (43.6% [SE 0.9] versus 31.5% [SE 0.3]; P<.001), but lower prevalence rates for jaw pain (3.6% [SE 03] versus 5.0% [SE 0.1]; P<.001), and migraine (10.0% [SE 0.5] versus 16.4% [SE 0.2]; P<0.001). Veterans (15.9% [SE 0.6]) and nonveterans (15.1% [SE 0.2]) had similar rates of neck pain.

Figure 2.

Differences in the Prevalence Rates of Selected Painful Health Conditions by Veteran Status. Footnotes: SE: Standard error. aP<.001. bP=.006.

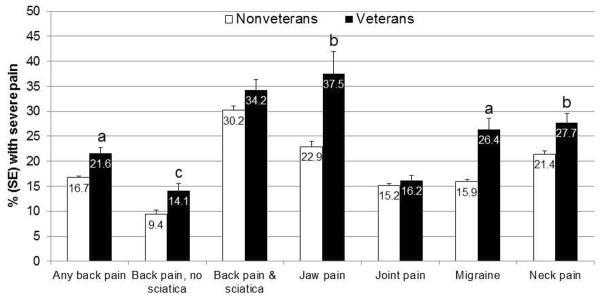

Figure 3 compares the prevalence of severe pain in Veterans and nonveterans with each pain-related condition examined. Veterans with any back pain were more likely to have severe pain (21.6% [SE 1.2]) than nonveterans (16.7% [SE 0.4]; P<.001). Both Veterans (14.1% [SE 1.4]) and nonveterans (9.4% [SE 0.8]) reporting BP w/o sciatica had relatively low prevalence rates for severe pain compared to the other conditions; however, the difference between the two groups was significant (P=.004). High rates of severe pain were seen in both Veterans (34.2% [SE 2.1]) and nonveterans (30.2% [SE 0.8]) reporting BP+sciatic but no difference was seen between groups (P=.08). As stated previously, fewer Veterans than nonveterans reported jaw pain (Figure 2); however those Veterans reporting jaw pain had a higher prevalence of severe pain (Figure 3: 37.5% [SE 4.5]) than did nonveterans (22.9% [SE 1.0]; P=.002). Although Veterans are more likely to report joint pain than nonveterans (Figure 2), no difference between the groups was seen in the prevalence of severe pain associated with this condition (P=.30). Veterans with migraine also had a significantly higher prevalence of severe pain than that seen in nonveterans (respectively, 26.4% [SE 2.1] versus 15.9% [SE 0.5]; P<.001). While Veterans and nonveterans were equally likely to report neck pain (Figure 2), Veterans with neck pain were more likely to report severe pain (27.7% [SE 1.9]) than were nonveterans (21.4 [0.6]; P=.002).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of Severe Pain in Veterans and Nonveterans by Health Condition. SE: Standard error. Footnotes: aP<.001. bP=.002. cP=.004.

DISCUSSION

Combining data from five consecutive years of the NHIS permitted us to compare the prevalence of pain in a population sample of 6,647 Veterans and 61,049 non-veterans. More Veterans than nonveterans reported having pain in the previous 3 months (Veterans 65.6%, nonveterans 56.4%). The rate of severe pain was almost 50% higher in Veterans (9.1%) than in nonveterans (6.3%). The difference was particularly striking for younger Veterans (18–39), who were substantially more likely to report suffering from severe pain than nonveterans of similar ages even after controlling for underlying demographic characteristics. This younger group of Veterans is undoubtedly overrepresented by those who served during the time of the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. While previous studies have identified painful health conditions as a significant burden among veterans, to our knowledge only three studies directly compared Veterans and nonveterans, and these studies have only looked at arthritis.8,18,30 Thus, the present data comparing the prevalence rates of back pain (with and without sciatica), jaw pain, joint pain (which only partially overlaps with arthritis pain), severe headaches and migraine, and neck pain in Veterans and non-Veterans are all unique observations. Also, while previous studies have compared overall health among US Military Veterans and nonveterans, this is the first study to directly compare the severity associated with painful health conditions amongst these groups. In this regard, the data address a need recognized in the US National Pain Strategy35 to go beyond simple studies of disease prevalence and instead “identify high-impact pain in both the general population and for anatomically defined painful conditions.”

The NHIS data does not permit inferences about whether differences in health care may contribute to the high prevalence of severe pain in younger Veterans. Increasing evidence is accumulating for the effectiveness of multidisciplinary pain management strategies,11,14,15,24,36,,41,42 including the VA’s own stepped care pain management approach,3 to manage severe chronic pain. In this regard, it is noted that younger Veterans are both less likely to have health insurance and less likely to receive care in Veteran’s administration facilities than older Veterans.1,45 These factors may limit the availability of multidisciplinary pain management strategies to younger Veterans.

Prospective studies have suggested that individuals with musculoskeletal injuries who are receiving disability compensation have worse outcomes than those not receiving compensation.2 A recent systematic review concluded that there was an association between compensation (and related factors) and poorer health after a musculoskeletal injury.29 Since, the NHIS does not capture information on whether individuals received any financial compensation for work- or service-related injuries, we were unable to explore the impact of these variables in our regression model. In particular, it would be informative to compare the prevalence with which Veterans receive compensation for service-related injuries versus compensation for work-related injuries in nonveterans. Depending on these two prevalence rates, our regression analysis might have either over- or under-estimated the differences in severe pain between Veterans and nonveterans.

This report not only offers important information on pain in Veterans from a large nationally representative dataset, but also provides some insights into pain severity associated with common pain-related conditions. In this regard, we are aware of only one other nationally representative survey that compared pain severity among different painful health conditions. Johannes et al.19 reported that 32% of individuals with lower back pain and 29% of those with arthritis had severe pain (defined as a score of 7+ on an 11-point Likert-type pain scale) in the last 3 months versus 16.6%–21.6% for back pain and 15.2%–16.2% for joint pain in the present study. However, the two studies had very different methodologies that might explain these differences. For instance, Johannes et al.19 was an Internet-based study with questions on pain severity and underlying health conditions limited to those who had pain lasting at least 6 months (which they defined as chronic pain). It is reasonable to expect that a cohort of individuals with chronic pain would report more severe pain than a cohort of the general population. Future studies using the Washington Group pain questions might directly assess the relationship between pain severity in individuals with either acute or chronic pain.

LIMITATIONS

For the combined years 2010–2014, the NHIS had a relatively high response rate of 62% for the randomly chosen “sample adult.” However, analyzes have shown that NHIS responders and non-responders differ on many characteristics.5 Some of these characteristics, such as older age (current analysis) and self-identifying as white,32 are related to both increasing levels of pain in the general population and to Veteran status (data not shown). While our regression analysis allowed us to control for confounding in responders, it did not mitigate any bias resulting from differential levels of pain in non-responders. The direction of this bias is unknown.

The current study has several limitations beyond those already mentioned. First, the data are cross-sectional and cannot prospectively assess clinical outcomes associated with pain severity. Second, since the NHIS did not collect pain treatment information, we were unable to determine whether differences in treatment could have further explained the difference in pain experiences of the participants. Third, although the NHIS sampling design allows for unbiased estimates of national trends, the data are limited to a noninstitutionalized population. Future research should consider nationally representative pain assessment for persons in VA facilities, nursing homes, hospices, and other residential healthcare facilities, since these persons are likely to be disproportionately affected with pain-related conditions. Fourth, the NHIS data do not identify any specific aspects of military service including whether a veteran had served in a combat role, their military occupation and rank, years of military service, and their branch of the armed forces (i.e., Army, Navy, Air Force, Marines). These factors likely impact pain prevalence and severity. It is also not possible to distinguish Veterans who were receiving outpatient care at VA facilities versus those who were not. It is known that Veterans using VA facilities have poorer health status (i.e., number of medical conditions, number of outpatient physician visits, number of hospital admissions) than Veterans not using these facilities.1

CONCLUSIONS

US military Veterans had higher pain prevalence and severity than nonveterans. These discrepancies appear particularly prominent among the youngest Veterans who likely served during the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The increased pain suffered by Veterans suggest that more attention should be paid to helping this population cope with their pain. It may be that some Veterans would benefit from a revised pain management plan that addresses the full range of biological, psychological, and social effects of pain on the individual.35 For others, additional services may be needed to help manage the impact of severe pain and related disability on daily activities. Successful implementation of the National Pain Strategy35 might facilitate both of these outcomes.

Highlights.

National estimates of severe pain are presented for U.S. Military veterans

Severe pain was about 50% higher in veterans than nonveterans

Veterans aged 18–39 were twice as likely to have severe pain than nonveterans

Veterans with back, jaw and migraine pain reported more severe pain than nonveterans

Acknowledgments

The author does not have a conflict to disclose. The author’s time and effort on this project were supported as part of his official duties as a federal employee. No other sources of funding were involved. The data contained within this report have not been previously reported in any other manuscript or meeting abstract.

The author thanks Ms. Danita Byrd-Clark, B.B.A., of Social & Scientific Systems, for her programming skills, and the many NCCIH staff who read and commented on earlier versions of this work.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The author performed this work as part of his official federal duties. No outside financial support was provided. The author has no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Agha Z, Lofgren RP, VanRuiswyk JV, Layde PM. Are patients at Veterans Affairs medical centers sicker? A comparative analysis of health status and medical resource use. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3252–3257. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.21.3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atlas SJ, Chang Y, Keller RB, Singer DE, Wu YA, Deyo RA. The impact of disability compensation on long-term treatment outcomes of patients with sciatica due to a lumbar disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2006;31:3061–9. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000250325.87083.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bair MJ, Ang D, Wu J, Outcalt SD, Sargent C, Kempf C, Froman A, Schmid AA, Damush TM, Yu Z, Davis LW, Kroenke K. Evaluation of stepped care for chronic pain (ESCAPE) in veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:682–689. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett DH, Boehmer TK, Boothe VL, Flanders WD, Barrett DH. Health-related quality of life of US military personnel: a population-based study. Mil Med. 2003;168:941–947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahlhamer JM, Simile CM. Proceedings of the Government Statistics Section, American Statistical Association. American Statistical Association; Washington, D.C: 2009. Subunit nonresponse in the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS): An exploration using paradata; pp. 262–276. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dobscha SK, Clark ME, Morasco BJ, Freeman M, Campbell R, Helfand M. Systematic review of the literature on pain in patients with polytrauma including traumatic brain injury. Pain Med. 2009;10:1200–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doebbeling BN, Clarke WR, Watson D, Torner JC, Woolson RF, Voelker MD, Barrett DH, Schwartz DA. Is there a Persian Gulf War syndrome? Evidence from a large population-based survey of veterans and nondeployed controls. Am J Med. 2000;108:695–704. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dominick KL, Golightly YM, Jackson GL. Arthritis prevalence and symptoms among US nonveterans, veterans, and veterans receiving Department of Veterans Affairs healthcare. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:348–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Economic and Social Commission for Asian and the Pacific. Results of the testing of the ESCAP/WG extended question set on disability. United Nations; [Accessed on May 26, 2016]. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/washington_group/resultsofthetestingoftheescap-wgquestionsetondisability.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisen SA, Kang HK, Murphy FM, Blanchard MS, Reda DJ, Henderson WG, Toomey R, Jackson LW, Alpern R, Parks BJ, Klimas N, Hall C, Pak HS, Hunter J, Karlinsky J, Battistone MJ, Lyons MJ Gulf War Study Participating Investigators. Gulf War veterans’ health: medical evaluation of a US cohort. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:881–890. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-142-11-200506070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flor H, Fydrich T, Turk DC. Efficacy of multidisciplinary pain treatment centers: a meta-analytic review. Pain. 1992;49:221–230. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Golightly YM, Dominick KL. Racial variations in self-reported osteoarthritis symptom severity among veterans. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005;17:264–269. doi: 10.1007/BF03324608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossbard JR, Lehavot K, Hoerster KD, Jakupack M, Seal KH. Relationships among veteran status, gender, and key health indicators in a national young adult sample. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:547–553. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.003002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunreben-Stempfle B, Griessinger N, Lang E, Muehlhans B, Sittl R, Ulrich K. Effectiveness of an intensive multidisciplinary headache treatment program. Headache. 2009;49:990–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haldorsen EM, Grasdal AL, Skouen JS, Risa AE, Kronholm K, Ursin H. Is there a right treatment for a particular patient group? Comparison of ordinary treatment, light multidisciplinary treatment, and extensive multidisciplinary treatment for long-term sick-listed employees with musculoskeletal pain. Pain. 2002;95:49–63. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(01)00374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haskell SG, Ning Y, Krebs E, Goulet J, Mattocks K, Kerns R, Brandt C. Prevalence of painful musculoskeletal conditions in female and male veterans in 7 years after return from deployment in Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom. Clin J Pain. 2012;28:163–167. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318223d951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Helmer DA, Chandler HK, Quigley KS, Blatt M, Teichman R, Lange G. Chronic widespread pain, mental health, and physical role function in OEF/OIF veterans. Pain Med. 2009;10:1174–1182. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2009.00723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoerster KD, Lehavot K, Simpson T, McFall M, Reider G, Nelson KM. Health and health behavior differences: US military, veteran, and civilian men. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43:483–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johannes CB, Le TK, Zhou X, Johnston JA, Dworkin RH. The prevalence of chronic pain in United States adults: results of an Internet-based survey. J Pain. 2010;11:1230–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang HK, Mahan CM, Lee KY, Magee CA, Murphy FM. Illnesses among United States veterans of the Gulf War: a population-based survey of 30,000 veterans. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42:491–501. doi: 10.1097/00043764-200005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kazis LE, Miller DR, Clark J, Skinner K, Lee A, Rogers W, Spiro A, 3rd, Payne S, Fincke G, Selim A, Linzer M. Health-related quality of life in patients served by the Department of Veterans Affairs: results from the Veterans Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.6.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kazis LE, Ren XS, Lee A, Skinner K, Rogers W, Clark J, Miller DR. Health status in VA patients: results from the Veterans Health Study. Am J Med Qual. 1999;14:28–38. doi: 10.1177/106286069901400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramarow EA, Pastor PN. The health of male veterans and nonveterans aged 25–64: United States, 2007–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012;101:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lang E, Liebig K, Kastner S, Neundörfer B, Heuschmann P. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation versus usual care for chronic low back pain in the community: effects on quality of life. Spine J. 2003;3:270–276. doi: 10.1016/s1529-9430(03)00028-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luncheon C, Zack M. Health-related quality of life among US veterans and civilians by race and ethnicity. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E108. doi: 10.5888/pcd9.110138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madans JH, Loeb M. Methods to improve international comparability of census and survey measures of disability. Disabil Rehabil. 2013;35:1070–1073. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2012.720353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madans JH, Loeb ME, Altman BM. Measuring disability and monitoring the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: the work of the Washington Group on Disability Statistics. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(suppl 4):S4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S4-S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller K, Loeb M. Mixed-method assessment of validity and cross-subgroup comparability. AAPOR 69th Annual Conference; Anaheim, CA. 2014. [Accessed September 27, 2016]. Available at: http://www.aapor.org/Conference-Events/Recent-Conferences.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murgatroyd DF, Casey PP, Cameron ID, Harris IA. The effect of financial compensation on health outcomes following musculoskeletal injury: systematic review. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0117597. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murphy LB, Helmick CG, Allen KD, Theis KA, Baker NA, Murray GR, Qin J, Hootman JM, Brady TJ, Barbour KE Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Arthritis among veterans - United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63:999–1003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murphy FM, Kang H, Dalager NA, Lee KY, Allen RE, Mather SH, Kizer KW. The health status of Gulf War veterans: lessons learned from the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Registry. Mil Med. 1999;164:327–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nahin RL. Estimates of pain prevalence and severity in adults: United States, 2012. J Pain. 2015;16:769–780. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nahin RL. Categorizing the severity of pain using questions from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. J Pain Res. 2016;9:105–113. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S99548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Center for Health Statistics. Data File Documentation, National Health Interview Survey, 2012. National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Hyattsville, Maryland: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health. A comprehensive population health-level strategy for pain. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Mar, 2016. [Accessed on August 29, 2016]. National Pain Strategy. https://iprcc.nih.gov/National_Pain_Strategy/NPS_Main.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patrick LE, Altmaier EM, Found EM. Long-term outcomes in multidisciplinary treatment of chronic low back pain: results of a 13-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:850–855. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200404150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Portenoy RK, Ugarte C, Fuller I, Haas G. Population-based survey of pain in the United States: differences among white, African American, and Hispanic subjects. J Pain. 2004;5:317–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reyes-Gibby CC, Aday LA, Todd KH, Cleeland CS, Anderson KO. Pain in aging community-dwelling adults in the United States: non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanics. J Pain. 2007;8:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riskowski JL. Associations of socioeconomic position and pain prevalence in the United States: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Pain Med. 2014;15:1508–1521. doi: 10.1111/pme.12528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rogers WH, Kazis LE, Miller DR, Skinner KM, Clark JA, Spiro A, 3rd, Fincke RG. Comparing the health status of VA and non-VA ambulatory patients: the Veterans’ Health and Medical Outcomes Studies. J Ambul Care Manage. 2004;27:249–262. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200407000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scascighini L, Toma V, Dober-Spielmann S, Sprott H. Multidisciplinary treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review of interventions and outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:670–678. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skouen JS, Grasdal AL, Haldorsen EM, Ursin H. Relative cost-effectiveness of extensive and light multidisciplinary treatment programs versus treatment as usual for patients with chronic low back pain on long-term sick leave: randomized controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:901–909. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200205010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steele L. Prevalence and patterns of Gulf War illness in Kansas veterans: association of symptoms with characteristics of person, place, and time of military service. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;152:992–1002. doi: 10.1093/aje/152.10.992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stuart JA, Murray KM, Ursano RJ, Wright KM. The Department of Defense’s Persian Gulf War registry year 2000: an examination of veterans’ health status. Mil Med. 2002;167:121–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsai J, Rosenheck R. Uninsured veterans who will need to obtain insurance coverage under the patient protection and affordable care act. Am J Public Health. 2014;104:e57–62. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.U.S. Census Bureau. [Accessed on May 26, 2016];2008–2010 American Community Survey. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_13_3YR_S0201&prodType=table.

- 47.Veterans Health Administration. [Accessed on May 6, 2016];Pain Management Strategy. Available at: http://www.va.gov/PAINMANAGEMENT/VHA_Pain_Management_Strategy.asp.

- 48. [Accessed September 27, 2016];Washington Group on Disability Statistics. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/washington_group.htm.