Abstract

Pheochromocytoma multisystem crisis is a rare and life-threatening disease that is associated with numerous symptoms and which is also difficult to diagnose. We herein report an autopsy case of a 61-year-old man who died due to pheochromocytoma multisystem crisis. The patient complained of vomiting and breathlessness. Computed tomography showed a shadow-like region with a similar appearance to interstitial pneumonia. The patient was diagnosed with takotsubo cardiomyopathy induced by severe lung disease based on the results of echocardiography and coronary angiography. The patient was treated for interstitial pneumonia. However, his condition rapidly deteriorated and he died 6 hours after arrival. We were later informed of his extremely high catecholamine serum levels. We found pheochromocytoma with hemorrhage at autopsy. The patient's lungs showed acute passive congestion with edema and extravasation.

Keywords: pheochromocytoma multisystem crisis, PMC, interstitial pneumonia, catecholamine induced cardiomyopathy

Introduction

Pheochromocytoma multisystem crisis (PMC) is an unusual state of pheochromocytoma. PMC is defined as the presence of hypertension or hypotension, high fever, encephalopathy and multi-organ failure. The successful treatment of PMC demands a prompt diagnosis. However, it is associated with numerous symptoms and is therefore difficult to diagnose.

We herein present the case of a man who presented with vomiting and breathlessness after working a night shift. His general condition and consciousness rapidly deteriorated and he developed multi-organ failure and died 6 hours after his initial presentation. We initially treated him for acute lung failure with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. However, his disease was subsequently diagnosed as PMC based on the autopsy findings. PMC is a rare disease. We identified the lung changes caused by a catecholamine storm at autopsy. In the present study we review and discuss the literature on PMC.

Case Report

A 61-year-old man was transported to our hospital by ambulance late at night. On the day before his admission, the patient was fine. Twelve hours prior to his admission, he worked a night shift. After returning home, he felt general fatigue and nausea. He subsequently vomited many times throughout the day, and began to feel breathless. At admission, his blood pressure was 170/110 mmHg and his heart rate was 132 beats per minute. Later, his blood pressure increased to 202/132 mmHg. At arrival his consciousness was almost clear, but it later became clouded and he developed a high fever. His respiratory condition rapidly deteriorated, to the point that it ultimately necessitated intubation.

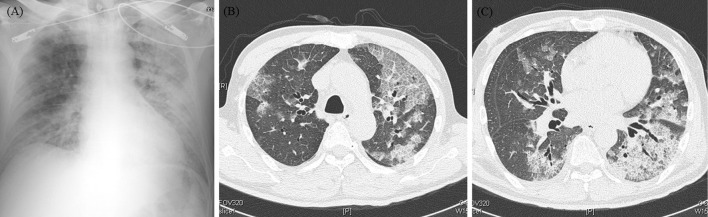

A blood analysis revealed the following findings: white blood cell (WBC), 19,800 /μL; C-reactive protein (CRP), 6.93 mg/dL; creatinine kinase, 741 IU/L (MB isozyme, 57 IU/L); troponin-I, 7.867 pg/mL (Table 1). Transthoracic echocardiography revealed diffuse severe hypokinesis at the mid-apex during left ventricular wall motion, in spite of a base of hyperkinesis. Acute coronary syndrome was suspected; we therefore performed cardio angiography, which revealed that the patient's coronary arteries were normal. Based on the above findings, we diagnosed the patient with takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Next, we performed chest X-ray and computed tomography examinations (Fig. 1) to investigate the cause disease. The chest X-ray film showed bilateral congestion and interstitial shadows, while computed tomography showed patchy ground glass opacity and bilateral infiltrative shadows and interstitial shadows. We diagnosed the patient's acute lung injury as interstitial pneumonia or severe bacterial pneumonia. We therefore administered methylprednisolone (1,000 mg) and meropenem (1 g). When we transferred him to the intensive care unit, his systolic blood pressure was 220 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure was 110 mmHg. We therefore thought that he did not require percutaneous cardiopulmonary support (PCPS) or intra-aortic balloon pumping (IABP). However, 2 hours later, he suddenly developed arrhythmia and his blood pressure decreased to 40 mmHg. Five minutes later, he went into cardiac arrest. We performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation, but there was no return of spontaneous circulation. There was no time to use PCPS or IABP. Our treatments were ineffective and he died 6 hours after arrival.

Figure 1.

(A): Chest X-ray showed congestion and interstitial shadow at bilateral. (B, C): Computed tomography shows patchy ground glass opacity and infiltrative shadow, partial bilateral interstitial shadows.

Table 1.

Laboratory Data on Arrival.

| Hematology | |||

| WBC | 19,800 | /μL | |

| RBC | 546*104 | /μL | |

| Hb | 15.7 | g/dL | |

| Ht | 46.4 | % | |

| Plt | 40.4*103 | /μL | |

| Coagulation | |||

| PT | 11.7 | sec | |

| APTT | 28.0 | sec | |

| Fib | 547.0 | mg/dlL | |

| D-dimer | 1.3 | μg/mL | |

| Serology | |||

| BNP | 407.4 | pg/mL | |

| HbA1c | 11.8 | % | |

| Biochemistry | ||

| TP | 6.9 | g/dL |

| Alb | 3.4 | g/dL |

| AST | 48 | IU/L |

| ALT | 24 | IU/L |

| LDH | 343 | IU/L |

| γGTP | 31 | IU/L |

| Tbil | 0.91 | mg/dL |

| CK | 741 | IU/L |

| CKMB | 57 | IU/L |

| BUN | 35.6 | mg/dL |

| Cre | 1.24 | mg/dL |

| Na | 131 | mEq/L |

| K | 4.6 | mEq/L |

| Cl | 94 | mEq/L |

| Ca | 9.0 | mg/dL |

| P | 4.2 | mg/dL |

| CRP | 6.93 | mg/dL |

| Troponin-I | 7.867 | pg/mL |

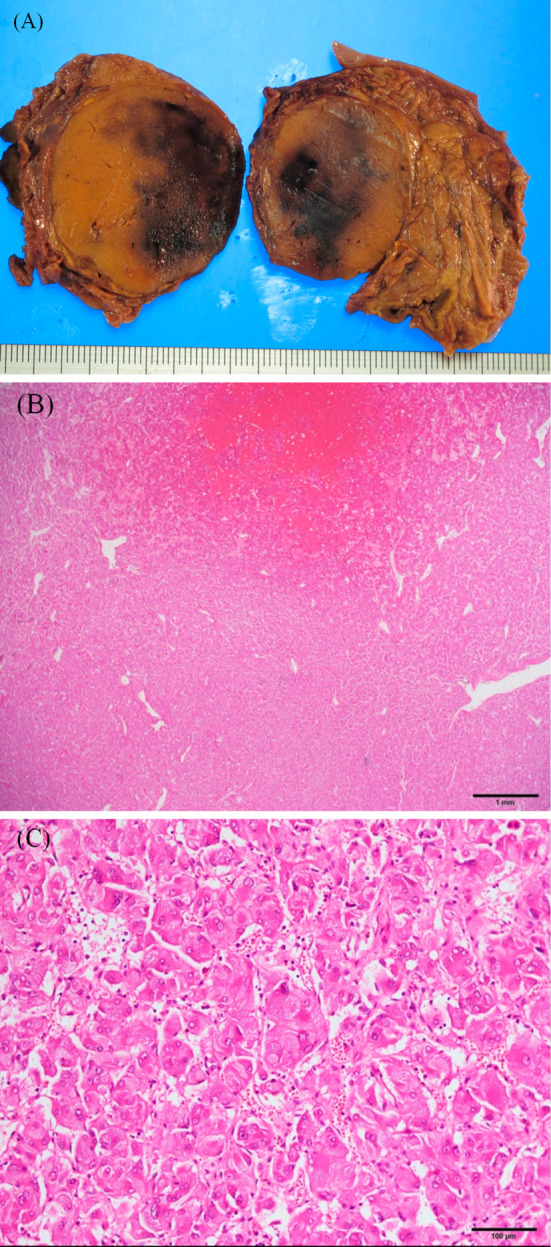

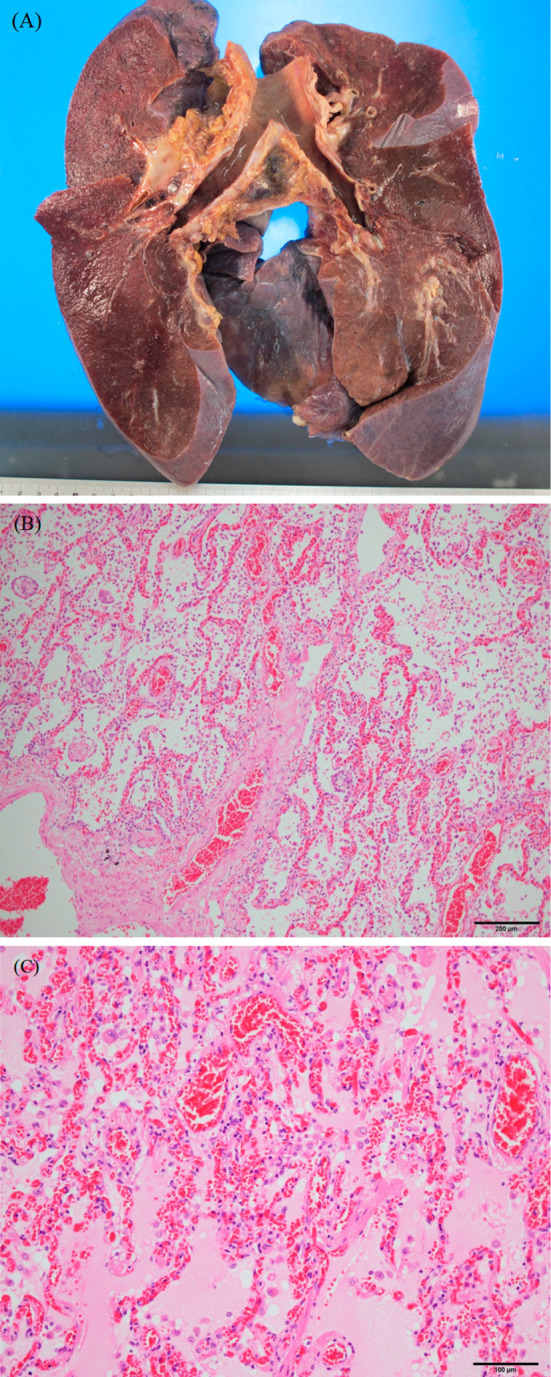

At autopsy, we found pheochromocytoma with hemorrhage of the right adrenal gland (Fig. 2). The patient's lungs showed acute passive congestion with edema and extravasation, without interstitial pneumonia (Fig. 3). The patient's heart had only mild extravasation but no changes. Later we found that his catecholamine serum levels were extremely high: epinephrine, 259,390 pg/mL (normal <100); nor-epinephrine, 278,690 pg/mL (normal <100-500), dopamine, 3,832 pg/mL (normal <30), KL-6, 3,860 U/mL (normal <500) (Table 2).

Figure 2.

(A): Right adrenal grand, contains 4 cm hemorrhagic tumor macro. (B), (C): Pheochromocytoma with hemorrhages.

Figure 3.

(A): Right and left lung; almost full of edema, contains little air, oneside of weight is 1,000 g. (B), (C): Severe congestion with edema and extravasation, fibrin-like thrombo materials in capillary.

Table 2.

Laboratory Data Later.

| Catecholamine | Normal range | |||

| Epinephrine | 259,390 | pg/mL | <100 | |

| Nor- Epinephrine | 278,690 | pg/mL | <100-500 | |

| Dopamine | 3,832 | pg/mL | <30 |

| Immunological | Normal range | ||

| PR3-ANCA | <1.0 | U/mL | <1.0 |

| MPO-ANCA | <1.0 | U/mL | <1.0 |

| KL-6 | 3,860 | U/mL | <500 |

Discussion

PMC is a severe type of pheochromocytoma crisis, which includes four components: multi-organ system failure, severe hypertension and/or hypotension, high fever and encephalopathy (1,2). PMC is considered to be a great mimic disease because it is associated with many symptoms and a severe condition. We need to include catecholamine cardiomyopathy caused by adrenal crisis in the differential diagnosis when there is unidentified takotsubo like cardiomyopathy without coronary artery stenosis. Because it involves an acute exacerbation, PMC is difficult to diagnose based on the results of an adrenal evaluation or the patient's hormone serum levels. Some case reports have shown that all surviving patients underwent surgery to remove a tumor (3). A case report showed that the use of an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) device improved a patient's condition and enabled elective surgery (4); ECMO is probably an effective measure in the treatment of PMC.

In the present case, the patient's respiratory condition rapidly deteriorated and were could not correctly diagnose the patient or decide to perform surgery. PMC was diagnosed at autopsy. Due to the rarity of PMC there are no reports about the combined lung findings of chest computed tomography and pathology. In this case, chest computed tomography revealed ground glass opacity and bilateral infiltrative shadows that were predominant on the left side and which partially contained interstitial shadows (Fig. 1). This finding is similar to that observed in patients with acute lung injury or acute respiratory distress syndrome. In the differential diagnosis, acute interstitial pneumonia, legionella pneumonia and alveolar hemorrhage were suspected based on the positon of the segmental shadow. Because the patient's general condition rapidly deteriorated, we treated him for acute interstitial pneumonia or a severe bacterial infection with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Although we administered steroids and antibiotics, they showed no clinical effect.

It is known that some drugs like steroids and D2 agonists as well as contrast agent and caffeine may cause an adrenal crisis (5-7). In the present case, the patient's medical history included hypertension and diabetes. His usual systolic blood pressure was 150 mmHg and his diastolic blood pressure was 80 mmHg. With regard to the patient's diabetes, he was being treated with a 4-drug combination therapy, but he had poor glycemic control and had refused the insulin treatment. Although the cause of his symptoms was not clear, it is considered possible that the administration of a contrast agent for coronary angiography and steroid pulse therapy hastened the progression of the disease.

Chest computed tomography showed various shadows, we evaluated the shadows pathologically. The lung pathological findings were severe pulmonary edema and capillary micro-hemorrhage. There was no interstitial pneumonia. A review article noted that the excessive secretion of catecholamine is responsible for several types of pulmonary edema (8,9), which are observed in adult respiratory distress syndrome. Pulmonary edema resulting from the excess secretion of catecholamine was the main cause of the patient's severe respiratory condition. In addition to this, exposure to excessive levels of catecholamine causes capillary shrinkage and micro-hemorrhage. In the present case, the patient's KL-6 level increased to 3,860 IU/L; however, the pathological examination revealed no interstitial changes. Elevated levels of KL-6 are seen in lung injury patients, especially those with ARDS (10). In the present case, the patient's elevated KL-6 level may have been the result of a lung injury induced by the excessive secretion of catecholamine. According to the above results, the lung shadows detected by computed tomography were considered to be severe pulmonary edema with capillary micro-hemorrhage induced by the excessive secretion of catecholamine that was revealed in the pathological examination.

In some cases, the excessive secretion of catecholamine causes severe pulmonary lung edema, including capillary micro-hemorrhage. There was some difficulty in diagnosing this condition by computed tomography. PMC is associated with various symptoms and mimics other conditions. When multiple organ system failure and high fever, encephalopathy, and blood pressure abnormalities are present, such as the findings that were observed in the present case, we need to consider the possibility of PMC.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Newell KA, Prinz RA, Pickleman J, et al. Pheochromocytoma Multisystem Crisis A Surgical Emergency. Arch Surg 123: 956-959, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whitelaw BC, Prague JK, Mustafa OG, et al. Phaeochromocytoma crisis. Clin Endocrinol 80: 13-22, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gundgurthi A, Gupta S, Garg MK, Ganguly P, Bhardwaj R. Unsuspected pheochromocytoma multisystem crisis: a fatal outcome in a young male patient. J Assoc Physicians India 60: 53-56, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Suh IW, Lee CW, Kim YH, et al. Catastrophic catecholamine-induced cardiomyopathy mimicking acute myocardial infarction, rescued by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in pheochromocytoma. J Korean Med Sci 23: 350-354, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rosas AL, Kasperlik-Zaluska AA, Papierska L, Bass BL, Pacak K, Eisenhofer G. Pheochromocytoma crisis induced by glucocorticoids: a report of four cases and review of the literature. Eur J Endocrinol 158: 423-429, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Del Rosso A, Fradella G, Russo L, et al. Pheochromocytoma crisis caused by contemporary ergotamine, caffeine, and nimesulide administration. Am J Med Sci 314: 396-398, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leow MK, Loh KC. Accidental provocation of phaeochromocytoma: the forgotten hazard of metoclopramide?. Singapore Med J 46: 557-560, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rassler B. Contribution of α-and β-adrenergic mechanisms to the development of pulmonary edema. Scientifica 2012: 829504, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rassler B. Role of α- and β-adrenergic mechanisms in the pathogenesis of pulmonary injuries characterized by edema, inflammation and fibrosis. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets 13: 197-207, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sato H, Callister ME, Mumby S, et al. KL-6 levels are elevated in plasma from patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Eur Respir J 23: 142-145, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]