Abstract

A 46-year-old woman with a history of Graves' disease presented with the chief complaints of appetite loss, weight loss, fatigue, nausea, and sweating. She was diagnosed with diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), thyroid storm, and influenza A. She was treated with an intravenous insulin drip, intravenous fluid therapy, intravenous hydrocortisone, oral potassium iodine, and oral methimazole. As methimazole-induced neutropenia was suspected, the patient underwent thyroidectomy. It is important to maintain awareness that thyroid storm and DKA can coexist. Furthermore, even patients who have relatively preserved insulin secretion can develop DKA if thyroid storm and infection develop simultaneously.

Keywords: diabetic ketoacidosis, thyroid storm, influenza, slowly progressive type 1 diabetes, autoimmune polyglandular syndrome

Introduction

Thyroid storm is a life-threatening situation with severe clinical manifestations of thyrotoxicosis, which leads to irreversible cardiovascular collapse due to a fever, tachycardia, and congestive heart failure (1). Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is also a life-threatening condition in which severe insulin deficiency leads to hyperglycemia, metabolic acidosis, dehydration, and electrolyte imbalances (2). The association between type 1 diabetes (T1D) and autoimmune thyroid diseases is well described and is a variant of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 3 variant (APS3v) (3). The simultaneous development of thyroid storm and DKA is relatively uncommon and a fulminant medical emergency that can result in a fatal outcome unless recognized and managed promptly.

Case Report

A 46-year-old woman with a history of Graves' disease (GD) was transferred to our emergency department on suspicion of DKA. She had noticed polydipsia, polyuria, and fatigue approximately four months prior to admission. She had also been suffering from a 1-month complaint of appetite loss, approximately 7 kg weight loss, fatigue, nausea, and sweating. Her medical history included GD, diagnosed at 42 years of age and managed with methimazole. However, she had poor compliance with anti-thyroid drugs. She denied a family history of thyroid diseases or diabetes. Three days before admission, she was also diagnosed with influenza A at a nearby hospital, and oseltamivir phosphate was prescribed.

At the emergency department, she presented with drowsiness and a body temperature of 37.0℃, blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg, heart rate of 200 bpm, respiratory rate of 32 breaths/min, oxygen saturation of 99% in 5 L nasal air, and a Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score of 14. Her clinical examination revealed a diffuse goiter with bilateral exophthalmoses. Her lungs were clear when auscultated. Her abdomen was soft and non-tender. Her skin was warm and wet. She had no lower extremity edema. The electrocardiogram showed marked tachycardia with atrial fibrillation, and a chest radiograph was normal. The laboratory data are shown in Table 1. Her initial laboratory data demonstrated marked metabolic acidosis, an increased plasma glucose level of 472 mg/dL, an increased HbA1c level of 13.7%, an increased free triiodothyronine level of 6.440 pg/mL, and a free thyroxine level of 2.830 ng/dL, with a suppressed thyrotropin (TSH) level of 0.005 μIU/mL. She scored 55 on the diagnostic criteria of Burch & Wartofsky for thyroid storm, and the diagnostic criteria of the Japan Thyroid Association for thyroid storm were also satisfied, since she had thyrotoxicosis, symptoms involving the central nervous system, tachycardia, and gastrointestinal symptoms (4). Accordingly, she was diagnosed with DKA and thyroid storm and admitted to the medical intensive care unit for further monitoring and treatment.

Table 1.

Laboratory Findings on Admission.

| Reference | Reference | ||||

| Diabetes | Blood Count | ||||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 472 | 80-112 | White blood cell (/μL) | 21,300 | 3,500-9,100 |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | 13.7 | 4.6-6.2 | Red blood cell (×104/μL) | 574 | 380-480 |

| Urinary C-peptide (μg/day) | 23.9 | 18.3-124.4 | Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 16.2 | 11.3-15.2 |

| GAD antibody (U/mL) | 896 | <1.5 | Platelet (×104/μL) | 17.2 | 13.0-36.9 |

| IA-2 antibody (U/mL) | 18 | <0.4 | |||

| Insulin autoantibody (nU/mL) | 191 | <125 | Blood Chemistry | ||

| Urinary ketone bodies | 4+ | (-) | Aspartate aminotransferase (IU/L) | 16 | 13-33 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 21 | 6-27 | |||

| Thyroid | Lactate dehydrogenase (IU/L) | 143 | 119-229 | ||

| Free triiodothyronine (pg/mL) | 6.440 | 2.300-4.000 | Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 438 | 115-359 |

| Free thyroxine (ng/dL) | 2.830 | 0.900-1.700 | γ-Glutamyl transferase (IU/L) | 25 | 10-47 |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone (μIU/mL) | 0.005 | 0.500-5.000 | Creatinine kinase (IU/L) | 25 | 45-163 |

| Thyrotropin receptor antibodies (IU/L) | 10.3 | <2 | Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 31.3 | 8.0-22.0 |

| Thyroglobulin antibodies (IU/mL) | 13 | <28 | Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.8 | 0.4-0.7 |

| Thyroid peroxidase antibodies (IU/mL) | 166 | <16 | Sodium (mEq/L) | 128 | 138-146 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.7 | 3.6-4.9 | |||

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 93 | 99-109 | |||

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | <0.3 | <0.3 | |||

| Arterial Blood Gas Analysis | |||||

| pH | 7.030 | 7.350-7.450 | |||

| Partial pressure of carbon dioxide (mmHg) | 13.4 | 35.0-45.0 | |||

| Partial pressure of oxygen (mmHg) | 160.0 | >75 | |||

| Bicarbonate (mmol/L) | 3.4 | 23.0-28.0 | |||

| Base excess (mmol/L) | -28.3 | -2.2-1.2 |

GAD: anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase, IA-2: anti-insulinoma antigen 2

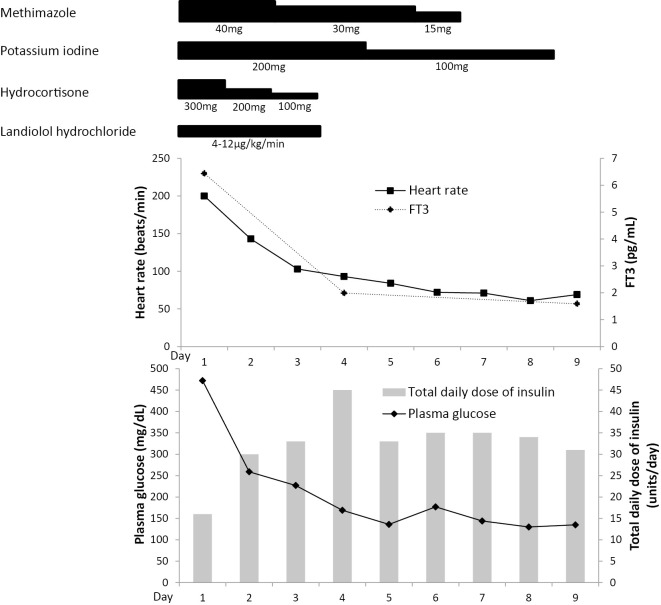

The clinical course is shown in Figure. She was treated with an intravenous insulin drip and aggressive intravenous fluid therapy. The thyroid storm with GD was treated with intravenous hydrocortisone 100 mg every 8 hours, oral potassium iodine 50 mg every 6 hours, and oral methimazole 20 mg every 6 hours. Since she had a history of asthma, landiolol hydrochloride, a short-acting beta-adrenoceptor blocker, was used at 4-12 μg/kg/min to control her heart rate. By Day 3, her tachycardia had resolved, and landiolol hydrochloride was discontinued. On Day 6, the white blood cell count had decreased to 2,800 cells/mm3 [neutrophils, 44.2% (1,238 cells/mm3)]. Methimazole was discontinued because methimazole-induced neutropenia was suspected. The patient was referred to an endocrine surgeon, and thyroidectomy was performed on Day 32. She was discharged from the hospital on Day 37 and maintained on multiple daily insulin infusion and levothyroxine sodium hydrate.

Figure.

The clinical course of the present case. FT3: free triiodothyronine

Further immunological investigation revealed elevated levels of anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD) antibody, anti-insulinoma antigen 2 (IA-2) antibody, and insulin autoantibody, consistent with T1D. The intravenous glucagon stimulation test was performed with blood samples for glucose and C-peptide taken at baseline and 6 minutes. Her plasma glucose levels were 139 and 152 mg/dL at baseline and 6 minutes, respectively. The corresponding serum C-peptide levels were 0.8 and 1.3 ng/mL at baseline and 6 minutes, respectively.

Discussion

The incidence of thyroid storm in hospitalized patients in Japan is estimated to be 0.20 per 100,000 per year, with a mortality rate of more than 10.7% (4). The association between autoimmune thyroid diseases and T1D is well known. Thyroid storm is precipitated by many factors, such as the irregular use or discontinuation of anti-thyroid drugs, infection, DKA, surgery, radioiodine therapy, adrenocortical insufficiency, and administration of iodinated contrast medium (5). The discontinuation of anti-thyroid drugs, infection, and DKA, three of the most common triggering factors of thyroid storm in Japan, were suspected as the triggering factors in the current case.

We performed a PubMed search of the English-language literature using a combination of “thyroid storm AND diabetic ketoacidosis”. Applying the diagnostic criteria of Burch & Wartofsky, a score of 45 or greater was considered to indicate thyroid storm. Eighteen English-language cases, including the present case, were considered to be cases of thyroid storm with DKA (Table 2) (6-20). The mean age of these cases was 37.4 years (male 2; female 16). Five cases (27.8%) were simultaneously diagnosed with GD and diabetes. Four cases (22.2%) had already been diagnosed with diabetes before the onset of GD. Seven cases (38.9%) had already been diagnosed with GD before the onset of diabetes, which was the same chronological order of the onset as the present case. One case (5.6%) had already been diagnosed with GD before the onset of impaired glucose tolerance (IGT). The chronological order of the onset was not mentioned in one case (5.6%).

Table 2.

Case Reports of Simultaneous Development of Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Thyroid Storm.

| Reference | Age | Sex | Past history | DM | AITD | Anti-thyroid drug compliance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (6) | 32 | F | GD | IGT | GD | Poor |

| (7) | 18 | F | - | T1D | GD | - |

| (7) | 31 | F | - | T1D | GD | - |

| (8) | 16 | M | T1D | T1D | GD | - |

| (9) | 18 | F | T1D → GD | T1D | GD | Poor |

| (10) | 48 | M | T2D, GD | T2D | GD | Poor |

| (11) | 25 | F | GD | T2D | GD | Not mentioned |

| (12) | 27 | F | GD → T1D | T1D | GD | Poor |

| (13) | 47 | F | - | T1D | GD | - |

| (14) | 29 | F | GD | T1D | GD | Poor |

| (15) | 22 | F | GD → T1D | T1D | GD | Poor |

| (15) | 18 | F | GD | T1D | GD | Poor |

| (16) | 79 | F | T2D → GD | T2D | GD | Poor |

| (17) | 56 | F | - | T1D | GD | - |

| (18) | 32 | F | GD | T1D | GD | Poor |

| (19) | 59 | F | - | T2D | GD | - |

| (20) | 71 | F | T2D | T2D | GD | - |

| Present case | 46 | F | GD | T1D | GD | Poor |

M: male, F: female, GD: Graves’ disease, AITD: autoimmune thyroid disease, T1D: type 1 diabetes mellitus, T2D: type 2 diabetes mellitus, IGT: impaired glucose tolerance

T1D → GD; The onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus preceded that of Graves’ disease.

T2D, GD; The chronological order of the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus and Graves’ disease was not mentioned.

GD → T1D; The onset of Graves’ disease preceded that of type 1 diabetes mellitus.

T2D → GD; The onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus preceded that of Graves’ disease.

The mean age at onset in the previous five cases in which GD was diagnosed before the onset of T1D was 25.6 years. Therefore, the age of onset in the present case of 46 years seems relatively old. Three of twelve cases with T1D in this literature review showed an age of onset of thyroid storm and DKA over 40 years; this lower number of cases is likely because the age of onset for T1D is generally young. However, the patient in the present study had noticed polydipsia, polyuria, and fatigue approximately four months before admission, when the onset of T1D was suspected.

The Japan Diabetes Society has proposed the following diagnostic criteria for slowly progressive insulin-dependent (type 1) diabetes mellitus (SPIDDM): the presence of GAD antibodies and/or islet cell autoantibodies at some time during the patient's clinical course and the absence of ketosis or ketoacidosis at the onset (or diagnosis) of diabetes mellitus without the need for insulin treatment to correct hyperglycemia immediately after diagnosis (21). The present case meets the diagnostic criteria of SPIDDM.

We previously reported the clinical characteristics of APS3v in the Japanese population. Among 30 patients with T1D and GD, 60% developed GD before the onset of T1D, 30% developed GD after the onset of T1D, and 10% developed T1D and GD simultaneously. A remarkable female dominance, a slower onset and older age onset of T1D, and higher prevalence of GAD were observed in APS3v patients compared to patients with T1D without autoimmune thyroid disease (22). Given that the duration from the onset of hyperglycemic symptoms to the initiation of insulin therapy was more than 4 months and that the absolute deficiency of insulin secretion was not suggested by urinary C-peptide and fasting serum C-peptide levels, the T1D in the present case seems to be SPIDDM rather than acute-onset T1D. Thyroid storm and infection might precipitate beta-cell destruction, leading to the need for insulin therapy to manage hyperglycemia starting at the time of diagnosis in patients with SPIDDM.

While new-onset T1D or the discontinuation of insulin in cases of established T1D commonly leads to the development of DKA, five cases in the literature review involved type 2 diabetes (T2D), and one case even involved IGT. It is interesting to note that not only T1D but also T2D and IGT, which are insulin-independent, can develop DKA and be the precipitating factor of thyroid storm. Thyroid hormone increases hepatic glucose output, decreases peripheral glucose disposal, increases pancreatic inactive insulin secretion, and increases renal insulin clearance (16). These mechanisms suggest that thyroid storm may affect glucose metabolism and lead to an insulin-dependent situation.

Baharoon et al. also reported H1N1 infection-induced thyroid storm, but the mechanism is not well understood (23). Since infection is one of the most widely-known precipitating factors for DKA, the infection of influenza A might have precipitated both thyroid storm and DKA in the present case. In all but 1 of 11 cases with a known history of GD, including the present case, anti-thyroid drug compliance was reported to be poor; therefore, drug compliance should be checked for patients with a history of GD.

The neutrophil count in the present case gradually decreased after admission. Methimazole was discontinued because methimazole-induced neutropenia was suspected, and thyroidectomy was performed. However, the administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) may be the treatment of choice before considering thyroidectomy. This is supported by the findings of Dai et al., who reported that G-CSF was effective in the treatment of antithyroid drug-induced agranulocytosis, based on a retrospective analysis of 18 cases (24). Nonetheless, infection due to agranulocytosis should be avoided, because infection complicated with DKA and thyroid storm can be fatal.

In conclusion, the simultaneous development of thyroid storm and DKA is a relatively uncommon and life-threatening situation. The clinical features of thyroid storm may be masked by DKA and infection, which makes diagnosis a clinical challenge. Nonetheless, it is important to be aware of the possibility of simultaneous development of DKA and thyroid storm in patients with a history of GD, since APS3v may be present. In addition, patients who have relatively preserved insulin secretion can develop DKA if thyroid storm and infection develop simultaneously.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Roth RN, McAuliffe MJ. Hyperthyroidism and thyroid storm. Emerg Med Clin North Am 7: 873-883, 1989. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Miles JM, Fisher JN. Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 32: 1335-1343, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huber A, Menconi F, Corathers S, Jacobson EM, Tomer Y. Joint genetic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes and autoimmune thyroiditis: from epidemiology to mechanisms. Endocr Rev 29: 697-725, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Akamizu T, Satoh T, Isozaki O, et al. Diagnostic criteria, clinical features, and incidence of thyroid storm based on nationwide surveys. Thyroid 22: 661-679, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Burch HB, Wartofsky L. Life-threatening thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid storm. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 22: 263-277, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hanscom DH, Ryan RJ. Thyrotoxic crisis and diabetic ketoacidosis; report of a case. N Engl J Med 257: 697-701, 1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bridgman JF, Pett S. Simultaneous presentation of thyrotoxic crisis and diabetic ketoacidosis. Postgrad Med J 56: 354-355, 1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mayfield RK, Sagel J, Colwell JA. Thyrotoxicosis without elevated serum triiodothyronine levels during diabetic ketoacidosis. Arch Intern Med 140: 408-410, 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ahmad N, Cohen MP. Thyroid storm with normal serum triiodothyronine level during diabetic ketoacidosis. JAMA 245: 2516-2517, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kunishige M, Sekimoto E, Komatsu M, Bando Y, Uehara H, Izumi K. Thyrotoxicosis masked by diabetic ketoacidosis: a fatal complication. Diabetes Care 24: 171, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee HL, Yu E, Guo HR. Simultaneous presentation of thyroid storm and diabetic ketoacidosis. Am J Emerg Med 19: 603-604, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sola E, Morillas C, Garzon S, Gomez-Balaguer M, Hernandez-Mijares A. Association between diabetic ketoacidosis and thyrotoxicosis. Acta Diabetol 39: 235-237, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lim D, Lunt H, Ojala R, Turner J. Simultaneous presentation of Type 1 diabetes and thyrotoxicosis as a medical emergency. N Z Med J 117: U775, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lin CH, Chen SC, Lee CC, Ko PC, Chen WJ. Thyroid storm concealing diabetic ketoacidosis leading to cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 63: 345-347, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yeo KF, Yang YS, Chen KS, Peng CH, Huang CN. Simultaneous presentation of thyrotoxicosis and diabetic ketoacidosis resulted in sudden cardiac arrest. Endocr J 54: 991-993, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Potenza M, Via MA, Yanagisawa RT. Excess thyroid hormone and carbohydrate metabolism. Endocr Pract 15: 254-262, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ahmad FA, Mukhopadhyay B. Simultaneous presentation of type 1 diabetes and Graves' disease. Scott Med J 56: 59, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gupta S, Kandpal SB. Case report: storm and acid, together... ! Am J Med Sci 342: 533-534, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Osada E, Hiroi N, Sue M, et al. Thyroid storm associated with Graves' disease covered by diabetic ketoacidosis: a case report. Thyroid Res 4: 8, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eliades M, El-Maouche D, Choudhary C, Zinsmeister B, Burman KD. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy associated with thyrotoxicosis: a case report and review of the literature. Thyroid 24: 383-389, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tanaka S, Ohmori M, Awata T, et al. Diagnostic criteria for slowly progressive insulin-dependent (type 1) diabetes mellitus (SPIDDM) (2012): report by the Committee on Slowly Progressive Insulin-Dependent (Type 1) Diabetes Mellitus of the Japan Diabetes Society. Diabetol Int 6: 1-7, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horie I, Kawasaki E, Ando T, et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 3 variant in the Japanese population. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97: E1043-E1050, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Baharoon SA. H1N1 infection-induced thyroid storm. Ann Thorac Med 5: 110-112, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dai WX, Zhang JD, Zhan SW, et al. Retrospective analysis of 18 cases of antithyroid drug (ATD)-induced agranulocytosis. Endocr J 49: 29-33, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]