Abstract

Diabetic ketoacidosis is characterized by hyperglycemia, anion-gap acidosis, and increased plasma ketones. After the resolution of hyperglycemia, persistent diuresis is rare. We herein report the case of a 27-year-old Asian woman with type 2 diabetes who was treated with a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor (canagliflozin) who developed euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis and persistent diuresis in the absence of hyperglycemia. Physicians should consider euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis in the differential diagnosis of patients treated with SGLT2 inhibitors.

Keywords: sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis

Introduction

Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors are oral hypoglycemic agents that augment the urinary excretion of glucose, thereby regulating glycemic control and promoting weight loss (1). SGLT2 inhibitors have an insulin-independent mechanism of action, which is being explored in patients with type 1 diabetes (2). Diabetic ketoacidosis is the most serious acute metabolic complication of diabetes (3). The incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis in patients treated with SGLT2 inhibitors is rare (4,5). Recently, the US Food and Drug Administration issued a Drug Safety Communication that SGLT2 inhibitors may lead to ketoacidosis with mild to moderate glucose elevation (euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis) (6). However, only a few cases of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis with persistent diuresis after the discontinuation of SGLT2 inhibitors have been reported. We herein report a case of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis with persistent diuresis in a diabetic patient undergoing treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor, canagliflozin.

Case Report

A 27-year-old woman of Asian descent from North America was admitted to our hospital for the treatment of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis. She had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 7 years previously. She had been taking oral antidiabetic drugs (gliclazide 300 mg, metformin 3,000 mg, and sitagliptin 150 mg per day), but her glycemic control was poor. Her endocrinologist recommended insulin treatment, but she refused. Three months prior to admission, she started taking canagliflozin (300 mg/day). During that time, she lost 3 kg and her urinary frequency increased. Two weeks prior to admission, she visited Japan for sightseeing. Two days before admission, she experienced dizziness, and the following day, she developed upper abdominal pain. On the day of admission, she visited the emergency department with complaints of thirst and malaise. Her family history revealed that her grandmother and grandfather both had type 2 diabetes. She did not smoke or drink alcohol, and she followed carbohydrate restriction for weight loss.

On examination, the patient's blood pressure was 145/103 mmHg, her heart rate was 123 beats/min, and her temperature was 36.2℃. Her weight, height, and body mass index were 63 kg, 150 cm, and 28 kg/m2, respectively. She was alert but lethargic, and her oral mucosa was dry. The other neurological and general examination results were normal. A urinalysis detected ketone bodies, while an arterial blood gas analysis showed high anion gap metabolic acidosis and a normal lactate level. Her biochemistry results revealed electrolyte disturbance and mild hyperglycemia (240 mg/dL). In addition, her HbA1c level was 9.9%, and her fasting serum C-peptide level was <0.1 ng/mL (reference range, 0.61-2.09 ng/mL); this finding indicated the severe impairment of insulin secretion. Her anti-glutamic acid decarboxylase antibody titer was also high (Table). Taken together, these findings were compatible with a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes mellitus and diabetic ketoacidosis without hyperglycemia.

Table.

The Patient’s Laboratory Data on Admission.

| Variable | Reference range | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Urianalysis (On admission) | |||

| Glucose | 4+ | ||

| Ketone | 3+ | ||

| Complete blood count (On admission) | |||

| White blood cell count | (/μL) | 23,010 | 3,900-9,800 |

| Neutrophils | (%) | 88.9 | 32-73 |

| Lymphocytes | (%) | 7.3 | 18-59 |

| Monocytes | (%) | 3.2 | 0-8 |

| Eosinophils | (%) | 0.2 | 0-6 |

| Basophils | (%) | 0.4 | 0-2 |

| Red blood cells | (×104/μL) | 590 | 427-570 |

| Hemoglobin | (g/dL) | 17.1 | 13.5-17.6 |

| Platelet count | (×104/μL) | 39.1 | 13.1-36.2 |

| Arterial blood gas analysis (On admission) | |||

| pH | 6.906 | 7.35-7.45 | |

| pCO2 | (mmHg) | 16.6 | 37.0-44.0 |

| pO2 | (mmHg) | 128.2 | 80-100 |

| Bicarbonate | (mmol/L) | 6.6 | 22-26 |

| Lactate | (mmol/L) | 1.94 | 0.5-2.0 |

| Base excess | (mmol/L) | -28.5 | -2-2 |

| Biochemistry (On admission) | |||

| Blood urea nitrogen | (mg/dL) | 23.5 | 8.0-22.0 |

| Creatinine | (mg/dL) | 0.64 | 0.31-1.1 |

| Na | (mEq/L) | 131 | 136-147 |

| K | (mEq/L) | 5.2 | 3.6-5.0 |

| Cl | (mEq/L) | 105 | 98-109 |

| Corrected Ca | (mg/dL) | 8.5 | 8.7-10.1 |

| Glucose | (mg/dL) | 240 | 70-109 |

| HbA1c | (%) | 9.9 | 4.5-6.1 |

| 3-hydroxybutyric acid | (mmol/L) | 7,220 | <74 |

| Endocrine-related tests | |||

| Serum CPR (Day 2 of treatment) | (ng/mL) | <0.1 | 0.61-2.09 |

| Anti-GAD antibody | (U/mL) | 187 | <1.5 |

CPR: C-peptide immunoreactivity, GAD: glutamic acid decarboxylase, HbA1c: glycated hemoglobin, pCO2: partial pressure of carbon dioxide, pO2: partial pressure of oxygen

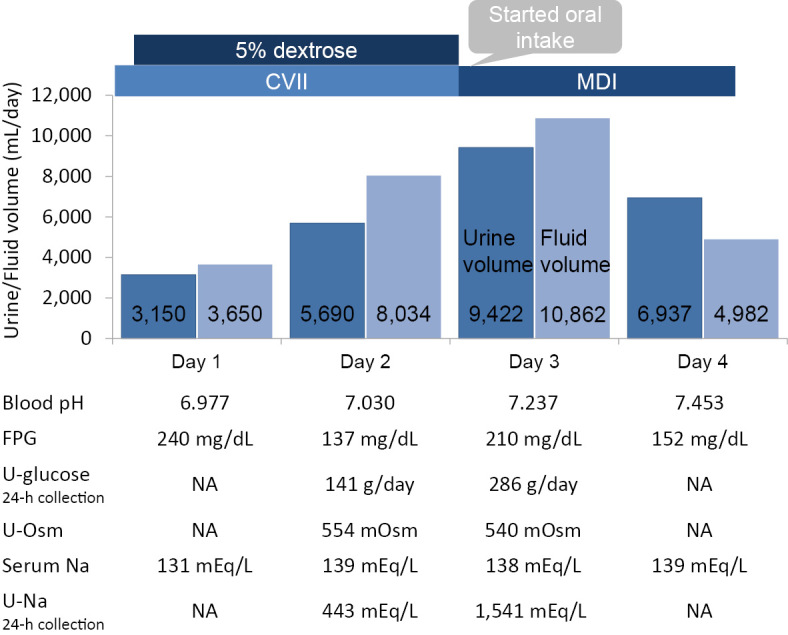

The patient was initially administered isotonic saline and a continuous insulin infusion with the discontinuation of all oral antidiabetic agents. An hour after the administration of saline and the insulin infusion, her glucose level decreased to <200 mg/dL; thus, an infusion 5% dextrose was initiated. On the following day, her venous blood pH level still showed acidemia, despite a normal glucose level, and her urine output was >5,000 mL/day. A urinalysis showed a high osmolality level due to glycosuria. Biochemical examinations showed normal levels of sodium and calcium. On day 3 of treatment, oral food intake was initiated and the continuous insulin infusion was switched to multiple daily injections of insulin. At this point, her urine output and urine glucose level increased further. We did not measure the patient's water consumption. However, we prohibited ad libitum water intake. On day 4 of treatment, her venous blood pH level recovered, and her urinary output peaked (Figure). We could not measure the urinary output after the fifth day of treatment due to the discontinuation of urinary catheterization and the patient's menstruation. On the eighth day of treatment, she was discharged but the nocturnal urination had not resolved.

Figure.

The course of osmotic diuresis in a patient with euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis who was treated with canagliflozin. On the second day of treatment, the patient’s urine output increased to over 5,000 mL in the absence of hyperglycemia. On the third day of treatment, oral food intake was initiated, and the patient’s urine output increased to over 9,000 mL. At this point, her osmotic diuresis peaked and her blood pH level recovered. CVII: continuous intravenous insulin infusion, eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate, FPG: fasting plasma glucose, MDI: multiple daily injections of insulin, NA: not available, U-glucose: urinary glucose, U-Osm: urine osmolality, Serum Na: serum sodium, U-Na: urinary sodium

Discussion

The present case highlights two important issues. First, SGLT2 inhibitors can provoke euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis. Second, euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis can accompany persistent diuresis after the administration of SGLT2 inhibitors is discontinued. To our knowledge, this is the first report of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis with persistent diuresis during treatment with an SGLT2 inhibitor.

Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis is defined as a blood glucose level of <300 mg/dL, and a plasma bicarbonate level ≤10 mEq/L (7). In a previous study of patients with type 2 diabetes, the incidence of diabetic ketoacidosis in patients treated with canagliflozin was more than twice as high as that in patients treated with antidiabetic drugs without canagliflozin (8). Only a few case reports have described the characteristics of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis due to the administration of SGLT2 inhibitors. The possible causative factors for euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis due to the administration of SGLT2 inhibitors include an insulin dose reduction, alcohol intake, and a low insulin secretion capability. Gastroparesis and a low-carbohydrate diet also can trigger euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis, especially among diabetic patients who do not use insulin (9-12). The time from the first dose of an SGLT2 inhibitor to the onset of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis has been reported to range from 2 to 13 days in diabetic patients who do not use insulin (9,11,12). In the present case, the patient had taken canagliflozin for 3 months. There are several possible reasons for the patient's development of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis, including her low adherence to treatment, the relatively acute autoimmune destruction of β cells, and her extreme carbohydrate restriction.

This patient experienced euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis with persistent diuresis via glycosuria, even after the discontinuation of the SGLT2 inhibitor. The possible mechanisms of this pathology are as follows: (1) her estimated glomerular filtration rate might have been increasing in association with early type 1 diabetes, thereby promoting glycosuria; (2) exogenous insulin may have augmented the effect of SGLT2 inhibition on glycosuria (13); and (3) canagliflozin delays the reversibility of SGLT2 inhibition in comparison to its short half-life (10-13 hours). In a previous case, Burr et al. reported that their patient had persistent glycosuria in the absence of hyperglycemia for 11 days after the discontinuation of an SGLT2 inhibitor (11). The volume of fluid therapy slightly exceeded the patient's urine output. The correction of hypovolemia is important for the treatment of diabetic ketoacidosis (3). In the present case, the patient received 3,650 mL of fluid in 12 hours of fluid therapy, which was reasonable from the point of view of treating diabetic ketoacidosis. After the second day of admission, fluid therapy was administered according to her urine volume. Thus, the volume of fluid that the patient received was appropriate for her clinical course. However, we did not rule out central diabetes insipidus. Previous studies have reported cases of central diabetes insipidus during diabetic ketoacidosis (14,15). In our case, the patient did not demonstrate hyponatremia or hypercalcemia leading to nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Thus, it remains unclear whether canagliflozin induced the patient's osmotic diuresis or masked central diabetes insipidus.

The insulin-independent actions of SGLT2 inhibitors are associated with short-term tolerability and the enhancement of urinary glucose excretion in patients with type 1 diabetes (2). On the other hand, off-label use of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 1 diabetes sometimes leads to euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis (6,9). In addition, SGLT2 inhibitor-treated type 2 diabetes patients who develop euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis are often misdiagnosed as having autoimmune diabetes (8). The possible pathophysiologic characteristics of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis due to SGLT2 inhibitors are as follows: (1) the urinary glucose excretion of patients with euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis due to the administration of SGLT2 inhibitors is more prominent than that in patients with diabetic ketoacidosis (13); (2) SGLT2 inhibitors inhibit the transportation of glucose into α cells, thereby enhancing the release of glucagon, resulting in ketogenesis; and (3) SGLT2 inhibitors may augment the renal tubular reabsorption of ketone bodies (1). In the present case, the patient's intake of canagliflozin, the restriction of carbohydrates, and low insulin secretion capability led to euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis. Clinicians should therefore be cautious when prescribing SGLT2 inhibitors to diabetic patients who restrict their intake of carbohydrates or who display insufficient insulin secretion.

In conclusion, the diuresis of the present patient with euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis persisted, even after the administration of the SGLT2 inhibitor was discontinued. The findings of this case emphasize that euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis should be considered in SGLT2 inhibitor-treated patients who develop nausea or fatigue. Furthermore, adequate hydration may enhance persistent diuresis via glycosuria in patients with euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis who are treated with SGLT2 inhibitors.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Taylor SI, Blau JE, Rother KI. SGLT2 inhibitors may predispose to ketoacidosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100: 2849-2852, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henry RR, Rosenstock J, Edelman S, et al. Exploring the potential of the SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin in type 1 diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Diabetes Care 38: 412-419, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kitabchi AE, Umpierrez GE, Miles JM, Fisher JN. Hyperglycemic crises in adult patients with diabetes. Diabetes Care 32: 1335-1343, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 373: 2117-2128, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Matthaei S, Catrinoiu D, Celiński A, et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of triple therapy with saxagliptin add-on to dapagliflozin plus metformin in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 38: 2018-2024, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA warns that SGLT2 inhibitors for diabetes may result in a serious condition of too much acid in the blood. [cited 2015 May 15]. Available from http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm446845.htm [Google Scholar]

- 7. Munro JF, Campbell IW, McCuish AC, Duncan LJ. Euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis. Br Med J 2: 578-580, 1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Erondu N, Desai M, Ways K, Meininger G. Diabetic ketoacidosis and related events in the canagliflozin type 2 diabetes clinical program. Diabetes Care 38: 1680-1686, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peters AL, Buschur EO, Buse JB, Cohan P, Diner JC, Hirsch IB. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis: a potential complication of treatment with sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibition. Diabetes Care 38: 1687-1693, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hine J, Paterson H, Abrol E, Russell-Jones D, Herring R. SGLT inhibition and euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 3: 503-504, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burr K, Nguyen AT, Rasouli N. A case report of ketoacidosis associated with canagliflozin (Invokana). Endocrine Society's Annual Meeting and Expo 2015: poster board SAT-595. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hayami T, Kato Y, Kamiya H, et al. Case of ketoacidosis by a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor in a diabetic patient with a low-carbohydrate diet. J Diabetes Investig 6: 587-590, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosenstock J, Ferrannini E. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis: a predictable, detectable, and preventable safety concern with SGLT2 inhibitors. Diabetes Care 38: 1638-1642, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sugiyama M, Yoshioka S, Mizoguchi A, Shinohara Y, Akahane K, Sato I. A case of type 2 diabetes patient with severe dehydration and diabetic ketoacidosis induced by excess intake of soft drinks due to coexisting central diabetes insipidus. J Japan Diab Soc 58: 835-841, 2015. (in Japanese, Abstract in English). [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shin HJ, Kim JH, Yi JH, Han SW, Kim HJ. Polyuria with the concurrent manifestation of central diabetes insipidus (CDI) & Type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM). Electrolyte Blood Press 10: 26-30, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]