Abstract

Although the influenza vaccine is relatively safe and effective, serious complications can develop in rare cases. We encountered two cases of interstitial pneumonia that developed after vaccination during the 2014-2015 influenza season. Overall, nine cases, including the two presented here, have been recorded in PubMed and the Cochrane library; eight patients were treated with corticosteroids, and all nine survived, suggesting a good prognosis. Interstitial pneumonia is rare; however, we found an increase in its incidence after 2009. Therefore, clinicians must be aware of the possibility of this complication and duly educate all patients in advance.

Keywords: bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, influenza A virus, H1N1 subtype, interstitial pneumonia

Introduction

Individuals worldwide receive the influenza vaccine because it decreases the incidence of influenza and the risk of more serious influenza-related complications (1,2). Although the safety and efficacy of this vaccine is well known, interstitial pneumonia can occasionally occur as a complication. We herein describe two cases of interstitial pneumonia secondary to the 2014-2015 seasonal influenza vaccine, which contained the A(H1N1)pdm09-like antigen, and present a review of similar reported cases.

Case Reports

Patient 1

In December 2014, a 71-year-old Japanese woman presented with severe, dry cough and left chest pain. She had received the seasonal influenza vaccine at another clinic 36 days before visiting our clinic, and the local injection site reaction was mild. She developed a dry cough the following day, and it gradually worsened. Two days before the first visit, she developed left chest pain. Her medical history revealed well-controlled diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia. She had undergone right nephrectomy for renal tuberculosis 37 years ago and had been prescribed rosuvastatin and linagliptin for the past 12 months.

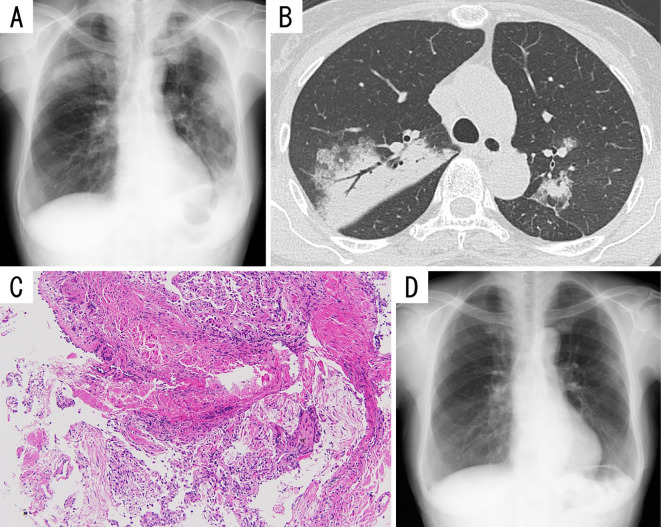

At the first visit, all her vital signs and physical features were normal. A complete blood count revealed mild leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 11,400/mm3) with normal white blood cell differentiation. Blood chemistry showed no abnormalities, including a normal lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level. Serological tests revealed the following: C-reactive protein (CRP), 5.54 mg/dL; soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2R), 1,086 U/mL; and surfactant protein-D, 178.2 ng/mL. Her serum surfactant protein-A (SP-A) and Krebs von den Lungen-6 (KL-6) levels were normal. Chest roentgenography (Fig. 1A) and computed tomography (Fig. 1B) showed patchy, peribronchial consolidations with air bronchograms and ground-glass opacities without pleural effusion in both lungs. Electrocardiogram and ultrasonic echocardiogram were normal. The severe cough followed by musculoskeletal chest pain precluded pulmonary function tests. Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) examination revealed 65% lymphocytes, 15% eosinophils, 19% macrophages, and 1% neutrophils, with no infectious organisms or malignant cells. The CD4+/CD8+ ratio was 2.1. Transbronchial lung biopsy revealed lymphocytic alveolitis and granulation tissue plugs within airspaces, suggesting organizing pneumonia (Fig. 1C). A drug lymphocyte stimulation test (DLST) performed using peripheral lymphocytes showed a positive reaction to the influenza vaccine, with a stimulation index of 190% (normal, <180%).

Figure 1.

Imaging and pathological findings of Patient 1. A) Chest radiograph showing patchy consolidations in both lungs. B) Chest computed tomography showing patchy, peribronchial consolidations with air bronchograms and ground-glass opacities in both lungs. C) Microphotographs of a specimen obtained via transbronchial lung biopsy showing lymphocytic alveolitis and plugs of granulation tissue within airspaces (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining; original magnification, ×100). D) Chest radiograph obtained after 10 months of follow-up showing almost complete resolution of the consolidations in both lungs.

Oral prednisolone at 35 mg (0.8 mg/kg/day) was administered daily, and within a week, our patient's symptoms and abnormal radiography and laboratory findings began resolving. We then performed pulmonary function tests and found a forced vital capacity (FVC) of 2.07 L (normal, 79.6% predicted), forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) of 1.68 L (normal, 88.0% predicted), and an FEV1/FVC ratio of 81.1%. Oral steroid therapy was tapered on an outpatient basis. Ten months after the treatment, her prednisolone dose was tapered. The patient remains healthy with no further symptoms or radiographic abnormalities (Fig. 1D), and she did not receive the annual influenza vaccine the following year.

Patient 2

In November 2014, a previously healthy 67-year-old Japanese man presented with a dry cough and dyspnea on exertion. He had received the seasonal influenza vaccine at another clinic 41 days prior to visiting our clinic, and the local injection site reaction was mild. Six days later, he developed a low-grade fever, general fatigue, and a dry cough, which gradually worsened. Nine days before admission, he visited an outpatient clinic with a severe, progressively worsening cough. Chest roentgenogram revealed patchy airspace infiltrations in both his lungs. Clarithromycin administered at 400 mg/day for 5 days was ineffective. His dyspnea on exertion gradually worsened, and he was referred to our outpatient clinic for further evaluation.

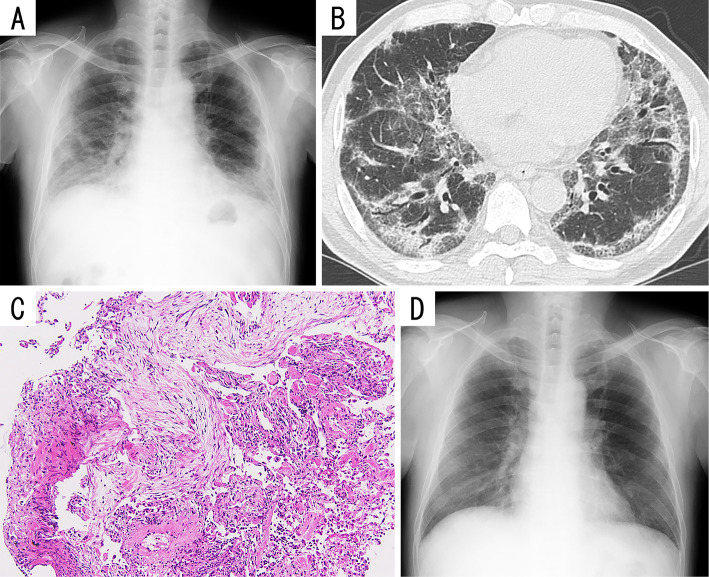

His medical history was unremarkable, and a chest roentgenogram obtained during a routine annual health check-up 7 months ago showed normal findings. On admission, his oxygen saturation was 93% in room air, and the other vital signs were normal. A physical examination revealed inspiratory fine crackles at both lung bases. A complete blood count revealed no abnormalities. Blood chemistry showed normal renal and liver function tests and an LDH level of 302 IU/L. Serological tests revealed the following: CRP, 2.95 mg/dL; ferritin, 701.1 ng/mL; sIL-2R, 670 U/mL; KL-6, 2,276 U/mL; SP-D, 160.6 ng/mL; and SP-A, 152.9 ng/mL. Chest roentgenography (Fig. 2A) and computed tomography (Fig. 2B) showed peripheral, predominantly basilar, and partially subpleural ground-glass opacities and consolidations without honeycomb changes in both lungs. The severe cough precluded carrying out pulmonary function tests. BALF examination revealed 49.3% lymphocytes, 15.5% eosinophils, 34.2% macrophages, and 1% neutrophils, without infectious organisms or malignant cells. The CD4+/CD8+ ratio was 0.7. Transbronchial lung biopsy confirmed lymphocytic alveolitis and scattered granulation tissue plugs within airspaces (Fig. 2C), with alveolar epithelial shedding and regenerative hyperplastic epithelia, suggesting organizing pneumonia with alveolar epithelial injury. A DLST performed using peripheral lymphocytes showed a positive reaction to the influenza vaccine, with a stimulation index of 330%.

Figure 2.

Imaging and pathological findings of Patient 2. A) Chest radiograph showing predominantly basilar consolidations in both lungs. B) Chest computed tomography scans showing peripheral, predominantly basilar, and partially subpleural ground-glass opacities and consolidations without honeycomb changes in both lungs. C) Microphotographs of a specimen obtained via transbronchial lung biopsy showing lymphocytic alveolitis and scattered plugs of granulation tissue (Hematoxylin and Eosin staining; original magnification, ×100). D) Chest radiograph obtained after 13 months of follow-up showing almost complete resolution of the consolidations in both lungs.

Intravenous methylprednisolone was administered at 1,000 mg daily for 3 days, followed by oral prednisolone at 40 mg (0.6 mg/kg/day) daily. His symptoms and radiographic and laboratory abnormalities gradually resolved, and oral steroid therapy was tapered on an outpatient basis. Thirteen months after treatment, his steroid dose was tapered off. The patient remains healthy with no further symptoms or radiographic abnormalities (Fig. 2D), and he did not get the annual influenza vaccine the following year.

Discussion

Influenza is a seasonal, contagious respiratory illness that is mostly mild and self-limited, although occasional severe manifestations may lead to hospitalization and even death. In 2009, there was a worldwide influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 pandemic with an increased propensity to infect the lower respiratory tract and the ability to cause the most serious form of acute respiratory distress syndrome secondary to pneumonia (3). Currently, the virus is seasonal in humans. Traditionally, the influenza vaccine is received by numerous individuals worldwide, particularly those at a high risk of developing influenza-related complications, because it decreases the incidence of the disease and the risk of more serious outcomes (1,2). The vaccine against the A(H1N1)pdm09 virus was developed in 2009, and its effectiveness and safety are considered to be similar to those of previous vaccines (4). In 2009, monovalent A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccines became available, followed by seasonal influenza vaccines containing the A(H1N1)pdm09-like antigen in 2010.

In the two cases described above, the patients were never smokers and had no history of allergy, recent visits abroad, or inhalation exposure. In addition, they reported no family history of pulmonary, allergic, or connective tissue diseases. Their serological tests were negative for several autoimmune markers such as antinuclear antibody, anti-double stranded DNA, anti-SS-A antibody, anti-SS-B antibody, anti-Scl-70 antibody, anti-centromere antibody, anti U1-ribonucleoprotein (RNP) antibody, anti-aminoacyl tRNA synthetase antibodies (including anti-Jo1 antibody), rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (proteinase-3 and myeloperoxidase). Paired serum tests were negative for current infection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae and psittaci, and Legionella pneumophila. Urine antigen tests were negative for Streptococcus pneumoniae and L. pneumophila. No pathogen was detected from the BALF by culture of general bacteria, acid-fast bacteria, and fungi; by loop-mediated isothermal amplification tests for M. pneumoniae and L. pneumophila; or by Luminex xTAGⓇ respiratory viral panel for Respiratory syncytial virus, Influenza virus A or B, Parainfluenza virus, Metapneumovirus, Adenovirus, Entero-Rhinovirus, Corona virus or Bocavirus.

In contrast, they met all of the following diagnostic criteria for drug-induced interstitial lung disease: correct identification of the drug; singularity of the drug; temporal eligibility; characteristic clinical, imaging, BALF, and pathological patterns of the reaction to the specific drug; and exclusion of other causes (5). Based on these findings, interstitial pneumonia associated with the influenza vaccine was diagnosed after excluding other causes of secondary interstitial pneumonia, such as infectious and connective tissue disease. The pathophysiology of drug-induced interstitial pneumonia, although not obvious, is believed to be cytotoxic or immune-mediated lung injury. The present two cases of interstitial pneumonia showed immune-mediated lung injury, as indicated by the lymphocytic and eosinophilic BALF and pathological findings of organizing pneumonia with alveolitis, positive DLST results for the influenza vaccine, and a good response to glucocorticoid therapy.

We performed a systematic search of PubMed and the Cochrane library to identify published reports on interstitial pneumonia associated with the influenza vaccine. Interstitial pneumonia is a rare complication of the influenza vaccine and was first described in association with this vaccine in 1998 (6). Our search identified 9 cases (5 men and 4 women; mean age, 62.2 years; age range, 38-75 years) of influenza vaccine-induced interstitial pneumonia, including the present 2. Three were associated with a vaccine without the A(H1N1)pdm09-like antigen (6-8) and six with a monovalent influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 vaccine or a vaccine containing the A(H1N1)pdm09-like antigen (9-12). Two patients had pre-existing interstitial pneumonia, chronic hypersensitive pneumonia, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Almost 50% of the patients were former smokers. Eight patients exhibited fever and some respiratory symptoms, including cough or dyspnea on exertion. The mean interval between symptom onset and vaccination was 3.25 (range, 1-7) days, while the median interval between vaccination and diagnosis was 10 (range, 2-41) days. Chest computed tomography was performed for seven patients: consolidations and ground-glass opacities were found in both lungs of six patients and only ground-glass opacities in both lungs of one. The lesion distribution varied among cases, including diffuse, predominantly peribronchovascular, and predominantly subpleural. Bronchofiber examination was performed for five patients. BALF examination revealed lymphocytosis and eosinophilia in three patients and only lymphocytosis in one. Transbronchial lung biopsy showed lymphocytic interstitial inflammation in four patients and/or organizing pneumonia (granulation tissue plugs within airspaces) in three. DLSTs, performed using peripheral blood lymphocytes for four patients and BALF lymphocytes for one, showed positive results. Eight patients were treated with systemic corticosteroids at varying initial doses, and three received steroid pulse therapy. Three patients-one pregnant woman and two with pre-existing interstitial pneumonia-required mechanical ventilation support. All nine patients survived, indicating a good prognosis.

In six of the nine cases reported, the patients were Japanese. This may be due to racial differences in the risk of drug-induced lung injury and better recognition of the complication by clinicians in Japan because of better awareness. An additional contributory factor may be the difficulty in excluding viral syndrome with high accuracy by performing a viral panel test, because the test is not approved by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and is not commercially available in Japan. However, the involvement of these factors is purely theoretical, and the real reason is currently unclear.

Several limitations associated with the present study warrant mention. First, we were unable to determine the antigen responsible for interstitial pneumonia onset. In the present two cases, interstitial pneumonia was associated with the 2014-2015 seasonal influenza vaccine, but this vaccine contains two influenza A antigens including A(H1N1)pdm09-like antigen, an influenza B antigen, and other additives such as preservatives. Therefore, we were unable to conclude that the A(H1N1)pdm09-like antigen increased the incidence of interstitial pneumonia. Second, the number of reported cases was relatively few, probably because of the difficulty in diagnosing drug-induced interstitial pneumonia.

In addition to published papers, we checked data pertaining to influenza vaccine-induced interstitial pneumonia on the website of the Vaccine Adverse Reporting System (VAERS) established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration (13). We found three cases in the VAERS database, all of which were primitively diagnosed with interstitial pneumonia secondary to a monovalent H1N1 vaccine or an influenza vaccine containing the H1N1-like antigen. None of the patients reported here were definitively diagnosed, and detailed reports are required for accumulating knowledge about interstitial pneumonia associated with the influenza vaccine.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that clinicians should be aware of the possibility of interstitial pneumonia as a complication of the influenza vaccine, ask closed questions about vaccination in medical interviews, and educate patients about this complication, as these will facilitate early detection and treatment. Although the safety of this vaccine has been confirmed, relatively newer drugs warrant further investigation to confirm their association with interstitial pneumonia.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

Acknowledgement

We thank Dr. Tamiko Takemura of the Department of Pathology at the Japanese Red Cross Medical Center for evaluating the pathological findings.

References

- 1. Manzoli L, Ioannidis JP, Flacco ME, De Vito C, Villari P. Effectiveness and harms of seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccines in children, adults and elderly: a critical review and re-analysis of 15 meta-analyses. Hum Vaccin Immunother 8: 851-862, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 12: 36-44, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bautista E, Chotpitayasunondh T, Gao Z, et al. ; Writing committee of the WHO consultation on clinical aspects of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza. . Clinical aspects of pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection. N Engl J Med 362: 1708-1719, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 12: 36-44, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Camus P, Fanton A, Bonniaud P, Camus C, Foucher P. Interstitial lung disease induced by drugs and radiation. Respiration 71: 301-326, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Johnston SD, Kempston A, Robinson TJ. Pneumonitis secondary to the influenza vaccine. Postgrad Med J 74: 541-542, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heinrichs D, Sennekamp J, Kirsten A, Kirsten D. Allergic alveolitis after influenza vaccination. Pneumologie 63: 508-511, 2009. (in German, Abstract in English). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kanemitsu Y, Kita H, Fuseya Y, et al. Interstitial pneumonitis caused by seasonal influenza vaccine. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi 48: 739-742, 2010. (in Japanese, Abstract in English). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bhurayanontachai R. Possible life-threatening adverse reaction to monovalent H1N1 vaccine. Crit Care 14: 422, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Umeda Y, Morikawa M, Anzai M, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis after pandemic influenza A (H1N1) vaccination. Intern Med 49: 2333-2336, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kumamoto T, Mitsuyama H, Hamasaki T. Case report; Drug induced lung injury caused by 2009 pandemic H1N1 vaccine. Nihon Naika Gakkai Zasshi 100: 3034-3037, 2011. (in Japanese). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Watanabe S, Waseda Y, Takato H, et al. Influenza vaccine-induced interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J 41: 474-477, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. US Department of Health and Human Services. Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) [Internet]. [cited 2015 Jan. 31]. Available from: http://vaers.hhs.gov/index.