Abstract

We herein report the case of a 57-year-old woman presenting with a biopsy-proven tumefactive demyelinating lesion as her first clinical event. Subsequently, she displayed a relapsing-remitting course with recurrence of large demyelinating lesions exceeding 2 cm in diameter rather than the small ovoid lesions characteristic of multiple sclerosis. Administration of interferon beta did not suppress the disease activity. Finally, treatment with natalizumab, which is a humanized monoclonal antibody against the cell-adhesion molecule α4-integrin, was initiated, resulting in clinical and radiological stabilization. Our experience here suggests that natalizumab may be an effective therapeutic option for relapsing-remitting tumefactive multiple sclerosis with high disease activity.

Keywords: tumefactive demyelinating lesions, natalizumab, recurrent, relapsing-remitting, multiple sclerosis

Introduction

Tumefactive demyelinating lesions (TDLs) are a rare inflammatory demyelinating disease of the central nervous system (CNS) that can mimic the clinical and radiological features of intracranial neoplasms (1). Therefore, brain biopsy is often needed for an accurate diagnosis, particularly if TDLs occur in patients without a pre-existing diagnosis of demyelinating disease, such as multiple sclerosis (MS) or neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD). Although TDLs are generally considered a single event, previous studies have indicated that the majority of patients with TDLs ultimately develop definite relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS; 2, 3). The management of tumefactive demyelinating disease is a challenge, as standardized guidelines do not exist. We herein report a patient with relapsing-remitting tumefactive MS characterized by recurrent large demyelinating lesions that successfully responded to natalizumab treatment.

Case Report

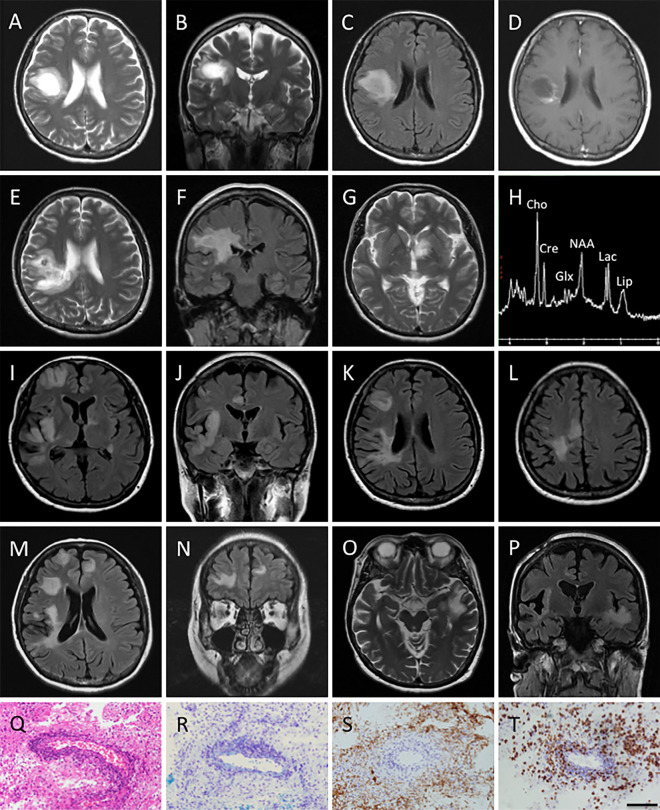

A 57-year-old woman with a 1-month history of slowly progressive left-sided hemiparesis visited another hospital in November 2013. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a well circumscribed rounded mass lesion in her right frontal lobe accompanied by mild perilesional edema (Figure A-D). Given the possibility of a brain tumor, she was transferred to the neurosurgical department of our hospital, and brain biopsy was performed. Histology revealed a loss of myelinated fibers with relative axonal preservation, lipid-laden macrophages, bizarre astrocytes, and perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltration (Figure Q-T) as well as occasional Creutzfeldt cells, findings compatible with tumefactive demyelination.

Figure.

A-C: Axial and coronal T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images, and axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI image obtained at the clinical onset reveal a high-intensity tumefactive lesion with mild perilesional edema in the right frontal lobe. D: Axial post-contrast T1-weighted MRI image obtained at clinical onset shows open ring enhancement. E-G: Axial T2 weighted and coronal FLAIR MRI images obtained on her first admission (2.5 months after the clinical onset) show enlargement of the pre-existing tumefactive lesion and a new hyper-intense lesion in the left basal ganglia. H: Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) performed on her first admission shows an abnormal elevation of the glutamate/glutamine (Glx) peaks, a decreased N-acetylaspartate (NAA) level, and elevation of the choline (Cho), lipid, and lactate levels. I-L: Axial and coronal FLAIR MRI images obtained on her second admission (9 months after the clinical onset) reveal multiple new tumefactive lesions in the right frontal and temporal lobe. M, N: Axial and coronal FLAIR MRI images obtained 2 weeks after her second admission show new lesions in the right frontal lobe. O, P: Axial T2-weighted and coronal FLAIR MRI images obtained on her third admission (13 months after the clinical onset) reveal a new high-intensity tumefactive lesion in the left temporal lobe. Q-T: Brain biopsy of the tumefactive lesion revealed the characteristic features of active inflammatory demyelination consisting of perivascular lymphocytic infiltration (Q; Hematoxylin and Eosin staining), gliosis of reactive astrocytes (Q), myelin loss (R; Kluver-Barrera), relative axonal preservation (S; neurofilament) and macrophage infiltration (T; CD68). Bars: 100 μm.

The patient's neurological status did not deteriorate until January 2014, when she began to suffer from progressive gait disturbance and rapid cognitive deterioration, and so she entered our department. A neurological examination uncovered left-sided paresthesia and motor weakness, and her mini mental state examination (MMSE) score was 14/30. A repeat MRI demonstrated an increase in the size of the pre-existing lesion (Figure E and F) and one new lesion in the left basal ganglia (Figure G). Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) showed an abnormal elevation of the glutamate/glutamine (Glx) peaks, a decreased N-acetylaspartate (NAA) level, and elevated levels of choline (Cho), lipids, and lactate (Figure H). Her spinal cord MRI was normal. A cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed a protein concentration of 62 mg/dL and a myelin basic protein (MBP) level of 712 pg/mL. Her glucose level was normal, and oligoclonal bands were negative. A diagnosis of tumefactive demyelinating disease was confirmed, and 3 courses of intravenous methylprednisolone pulse (IVMP) therapy (1,000 mg/day for 3 days) were started, followed by maintenance therapy with oral prednisolone (PSL; 30 mg/day). Consequently, her gait disturbance improved, and her MMSE score increased to 19/30. Thereafter, the patient's serum collected on admission was reported as being negative for anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibody as assessed by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. The PSL dosage was tapered by 5 mg every month thereafter.

Six months later, she presented with memory impairment and topographic disorientation. Her MMSE score had dropped back to 14/30. Furthermore, her mental activity had gradually decreased, and she had become apathetic. The PSL dose at that time was 5 mg/day. Brain MRI showed multiple new lesions involving both cortical gray and white matter in the right frontal and temporal lobes; however, the pre-existing lesion in the left basal ganglia had decreased in size (Figure I-L). Laboratory studies did not provide any evidence suggestive of vasculitis. Serology for cytomegalovirus, toxoplasma, and human immunodeficiency virus was negative. A CSF sample showed elevated MBP (615 pg/mL) and was negative for cultures, cytology, and viruses, including JC polyomavirus, based on the results of polymerase chain reactions. Again, the findings for oligoclonal bands and anti-AQP4 antibody were negative. As 3 courses of IVMP therapy did not ameliorate the disease progression (her MMSE score decreased to 7/30) and follow-up MRI revealed another new lesion in the left frontal lobe (Figure M and N), plasma exchange (PLEX) therapy was subsequently initiated, resulting in improvements in her mental and cognitive dysfunction. She became able to walk unassisted, and her MMSE recovered from 7/30 to 17/30 following completion of the seventh PLEX cycle. She was discharged on a weekly regimen of intramuscular injections of interferon beta-1a (IFNβ-1a) in November 2014.

One month later, she developed excessive self-talk and hyperorality. Another brain MRI disclosed an additional lesion in the left temporal lobe (Figure O and P), leading to the discontinuation of IFNβ-1a therapy. Three additional courses of IVMP and 7 cycles of PLEX improved her symptoms partially. At this time, intravenous treatment with 300 mg of natalizumab once every 4 weeks was initiated. Her clinical condition did not respond to this natalizumab therapy, but follow-up MRI revealed a reduction in the size of the left temporal lesion. She became stable with neither clinical relapse nor new MRI lesions throughout the following 16 months of clinical follow-up.

Discussion

Our patient presented with pathologically confirmed TDL and recurrently developed multiple cortical and subcortical lesions, despite short-term positive responses to IVMP and PLEX. The radiological characteristics of TDLs are lesions a diameter larger than 2 cm, located mainly in white matter, with varying degrees of mass effect or perilesional edema and often complete or incomplete ring enhancement (2). The initial lesions in the present case had these MRI characteristics consistent with a diagnosis of TDLs. However, the recurrent lesions were large, intracranial ones exceeding 2 cm in size, although these lesions did not resemble brain tumors. MRS of the TDLs may cause a decrease in the NAA/creatine (Cr) ratio and an increase in the Cho/Cr ratio, but this is also a common finding in gliomas (4). A few previous reports have indicated that an abnormal elevation of the Glx peaks appears to favor TDLs (5,6), a finding which was in accordance with our results.

Recurrence of a tumefactive lesion itself is infrequent in patients who present with a tumefactive lesion. Altintas et al. stated that only 16.7% of patients developed new lesions exceeding 2 cm in diameter, with a median follow-up of 38 months after the first attack with TDL (3). In addition, Jeong et al. reported that only 16.1% of 31 patients with initially diagnosed TDL developed new lesions exceeding 2 cm in diameter over a median follow-up period of about 38 months (7). Our patient had a third large demyelinating attack during the first year of follow-up. Our case met the 2010 McDonald criteria for MS (8), as there were two or more attacks disseminated in time and space with clinical evidence of two or more lesions. However, a diagnosis of MS appeared unlikely, as there were several discrepancies between the present case and typical MS cases, including the superficial gray matter involvement, the presence of recurrent large demyelinating lesions, the absence of small ovoid lesions typical of MS, the lack of oligoclonal bands in the CSF, and the unresponsiveness to IFNβ-1a therapy, which has been demonstrated to have beneficial effects in RRMS patients. Anti-AQP4 antibody was not found, but the presence of anti-Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody has not yet been investigated in our case. Given that autoantibodies against MOG are reportedly found in patients with acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, MS, and AQP4-seronegative NMOSD (9), further analysis and longer follow-up will be required for a definitive clinical diagnosis of MS.

There is no standard immunomodulatory treatment for patient with TDLs. Hardy et al. proposed an algorithm for the acute management using IVMP and/or PLEX followed by disease modification with IFNβ or glatiramer acetate (GA; 1). After initial treatment with IVMP, our patient showed remarkable improvement. As TDLs have also been reported as a first clinical event in patients with NMOSD (10,11), we decided to continue the maintenance therapy with oral PSL after pulse therapy. However, the possibility of NMOSD was excluded based on the diagnostic criteria (12) and serologic test findings for AQP4 antibody, and so oral PSL was tapered. Six months later, when the PSL dose had been reduced to 5 mg/day during tapering, the patient relapsed severely. She had no clinical response to IVMP but did show improvement with PLEX. We commenced IFNβ-1a treatment to prevent the attacks as disease modification therapy (DMT), but she experienced another event 1 month after the start of IFNβ-1a. At present, second-line DMTs, such as fingolimod and natalizumab, are available in Japan. Given the increasing evidence of an association between TDLs and fingolimod treatment (13-15) and the fact that natalizumab has been recommended for the treatment of RRMS in patients with not only insufficient response to IFNβ/GA but also aggressive MS (16), we decided to initiate natalizumab therapy, regardless of the lack of seropositivity for JC polyomavirus. In our case, treatment with natalizumab effectively suppressed disease activity. Although the clinical outcomes have only been reported in a few cases, natalizumab seems to be effective in treating patients with relapsing-remitting TDLs (17-19). The findings in our present case further suggest that natalizumab may also be used to prevent new events as an immunomodulatory treatment for tumefactive demyelination with relapsing episodes.

In conclusion, we presented a case of rapidly evolving severe relapsing-remitting tumefactive MS, where the patient showed no evidence of disease activity after the initiation of natalizumab treatment. The management of tumefactive demyelinating disease can be a challenge, as TDLs are pathologically heterogeneous. When a diagnosis of relapsing MS is supported, we should consider natalizumab therapy as soon as possible for patients presenting with recurrent large demyelinating lesions. However, further studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of this monoclonal antibody.

The authors state that they have no Conflict of Interest (COI).

References

- 1. Hardy TA, Chataway J. Tumefactive demyelination: an approach to diagnosis and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 84: 1047-1053, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lucchinetti CF, Gavrilova RH, Metz I, et al. Clinical and radiographic spectrum of pathologically confirmed tumefactive multiple sclerosis. Brain 131: 1759-1775, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Altintas A, Petek B, Isik N, et al. Clinical and radiological characteristics of tumefactive demyelinating lesions: follow-up study. Mult Scler 18: 1448-1453, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Law M, Meltzer DE, Cha S. Spectroscopic magnetic resonance imaging of a tumefactive demyelinating lesion. Neuroradiology 44: 986-989, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cianfoni A, Niku S, Imbesi SG. Metabolite findings in tumefactive demyelinating lesions utilizing short echo time proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 28: 272-277, 2007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yamashita S, Kimura E, Hirano T, Uchino M. Tumefactive multiple sclerosis. Intern Med 48: 1113-1114, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jeong IH, Kim SH, Hyun JW, Joung A, Cho HJ, Kim HJ. Tumefactive demyelinating lesions as a first clinical event: Clinical, imaging, and follow-up observations. J Neurol Sci 358: 118-124, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 69: 292-302, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reindl M, Di Pauli F, Rostásy K, Berger T. The spectrum of MOG autoantibody-associated demyelinating diseases. Nat Rev Neurol 9: 455-461, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kim SH, Kim W, Kook MC, Hong EK, Kim HJ. Central nervous system aquaporin-4 autoimmunity presenting with an isolated cerebral abnormality. Mult Scler 18: 1340-1343, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ikeda K, Ito H, Hidaka T, et al. Repeated non-enhancing tumefactive lesions in a patient with a neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Intern Med 50: 1061-1064, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG. Revised diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica. Neurology 66: 1485-1489, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Visser F, Wattjes MP, Pouwels PJ, Linssen WH, van Oosten BW. Tumefactive multiple sclerosis lesions under fingolimod treatment. Neurology 79: 2000-2003, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pilz G, Harrer A, Wipfler P, et al. Tumefactive MS lesions under fingolimod: a case report and literature review. Neurology 81: 1654-1658, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harirchian MH, Taalimi A, Siroos B. Emerging tumefactive MS after switching therapy from interferon-beta to fingolimod: A case report. Mult Scler Relat Disord 4: 400-402, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kappos L, Bates D, Edan G, et al. Natalizumab treatment for multiple sclerosis: updated recommendations for patient selection and monitoring. Lancet Neurol 10: 745-758, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. La Puma D, Llufriu S, Sepúlveda M, et al. Long-term follow-up of immunotherapy-unresponsive recurrent tumefactive demyelination. J Neurol Sci 352: 127-128, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gnanapavan S, Jaunmuktane Z, Baruteau KP, Gnanasambandam S, Schmierer K. A rare presentation of atypical demyelination: tumefactive multiple sclerosis causing Gerstmann's syndrome. BMC Neurol 14: 68, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Seifert CL, Wegner C, Sprenger T, et al. Favourable response to plasma exchange in tumefactive CNS demyelination with delayed B-cell response. Mult Scler 18: 1045-1049, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]