Abstract

Objectives

Investigate the prevalence of obesity in Italy and examine its resource consumption and economic impact on the Italian national healthcare system (NHS).

Design

Retrospective, observational and real-life study.

Setting

Data from three health units from Northern (Bergamo, Lombardy), Central (Grosseto, Tuscany) and Southern (Naples, Campania) Italy.

Participants

All patients aged ≥18 years with at least one recorded body mass index (BMI) measurement between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2012 were included.

Interventions

Information retrieved from the databases included primary care data, medical prescriptions, specialist consultations and hospital discharge records from 2009–2013. Costs associated with these data were also calculated. Data are presented for two time periods (1 year after BMI measurement and study end).

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Primary—to estimate health resources consumption and the associated economic impact on the Italian NHS. Secondary—the prevalence and characteristics of subjects by BMI category.

Results

20 159 adult subjects with at least one documented BMI measurement. Subjects with BMI ≥30 kg/m2 were defined as obese. The prevalence of obesity was 22.2% (N=4471) and increased with age. At the 1-year observation period, obese subjects who did not receive treatment for their obesity experienced longer durations of hospitalisation (median length: 5 days vs 3 days), used more prescription drugs (75.0% vs 57.7%), required more specialised outpatient healthcare (mean number: 5.3 vs 4.4) and were associated with greater costs, primarily owing to prescription drugs and hospital admissions (mean annual cost per year per patient: €460.6 vs €288.0 for drug prescriptions, €422.7 vs € 279.2 for hospitalisations and €283.2 vs €251.7 for outpatient care), compared with normal weight subjects. Similar findings were observed for the period up to data cut-off (mean follow-up of 2.7 years).

Conclusions

Untreated obesity has a significant economic impact on the Italian healthcare system, highlighting the need to raise awareness and proactively treat obese subjects.

Keywords: Obesity, Body mass index, Healthcare resource consumption, Retrospective, Real-life study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large study on more than 20 000 subjects;

Real-world data coming from local health units;

Data retrieved from different geographical areas;

Direct evaluation of costs by integrating multiple data sources

Limitations due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Introduction

Obesity is now widely regarded as a global epidemic; worldwide, obesity rates have more than doubled since 1980.1 2 According to the WHO, more than 1·9 billion adults were overweight in 2014. Of these, over 600 million (∼13% of the world's population) were obese, defined as having a body mass index (BMI) of ≥30 kg/m2.1 In Italy, WHO reports from 2014 showed that the prevalence of obesity was 20.4% among individuals aged ≥18 years.3 Obesity is a major risk factor for various chronic diseases, particularly if it remains untreated. Globally, 44% of diabetes, 23% of ischaemic heart disease and 7–41% of certain cancers are attributable to being overweight or obese.1 Obesity-associated mortality rates are also alarmingly high, with at least 2.8 million deaths each year resulting from being overweight or obese.1 Obesity was once considered to be an issue associated with high-income countries only; however, its prevalence is now also increasing in low-income and middle-income countries.4

Previous studies have shown that obesity and its associated comorbidities have a considerable economic impact on healthcare systems, primarily because of high costs for medication and hospitalisations.5–8 However, in those studies, costs were only estimated indirectly. In contrast, we report here on the findings from a study of over 20 000 adults that investigated the prevalence of, and direct costs associated with, untreated obesity in three distinct regions of Italy—which differ in terms of geography and nutritional traditions—in order to understand the healthcare usage and economic impact of obesity on the Italian national healthcare system (NHS).

Methods

Study design and population

This was a retrospective, observational and real-life study. To be eligible, individuals were required to be aged ≥18 years and to have at least one recorded BMI measurement between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2012. The first recorded BMI was set as the index date. Eligible subjects were identified from registries at three Italian local health units that represent the primary Italian geographical areas: Bergamo, Lombardy (northern Italy), Grosseto, Tuscany (central Italy) and Naples, Campania (southern Italy).

BMI was classified as follows: underweight, <18.5 kg/m2; normal weight, ≥18.5 to <25 kg/m2; overweight, ≥25 to <30 kg/m2 and obese, ≥30 kg/m2. Obesity was further classified as grade I, II and III based on BMI levels of ≥30 to <35 kg/m2, ≥35 to <40 kg/m2 and ≥40 kg/m2, respectively.9

An anonymous data file is routinely used by regional health authorities for epidemiological and administrative purposes. No identifiers related to subjects were provided to the researchers. In accordance with Italian law regarding data confidentiality,10 the ethics committee of each local health units was notified about the study.

Study objective

The primary objective of the study was to estimate health resource consumption and the economic impact of obesity on the Italian NHS. The secondary objective was to assess the prevalence and characteristics of subjects in relationship with the BMI category.

Data sources and analysis

Primary care data for each subject were retrospectively collected from the Health Search Database of the Società Italiana di Medicina Generale (Italian Society of General Medicine) for the period 2009–2013. Using the numeric code assigned to each citizen by the local health units as a unique identifier, this database was linked to the following databases: (1) Medications Prescription Database, which includes anatomical–therapeutic–chemical (ATC) codes; (2) Hospital Discharge Database, which includes dates of hospital admission and discharge, as well as discharge diagnosis codes according to the International Classification of Diseases Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM); (3) Laboratory Tests and Specialist Visits Database; (4) Mortality Database, from which data on mortality, but not cause of death, were collected and (5) Beneficiaries' Database, from which data regarding date of birth, sex and place of residence were collected.

Data on drug use, hospitalisations, use of specialist services and treatment costs were evaluated from the index date until 31 December 2013, corresponding to a period of at least 12 months and up to 5 years (the date of last enrolment was 31 December 2012). Specialist services encompassed all specialised outpatient healthcare, including diagnostic and laboratory tests (such as X-ray, ultrasound, MRI, blood and urinary tests), and consultations by specialist healthcare providers. The cost analysis was conducted from the perspective of the NHS. Costs are reported in Euros (€). Drug costs were evaluated based on the Italian NHS costs at the time of the analysis. Outpatient services costs were evaluated according to regional tariffs. Hospitalisation costs were calculated using the diagnosis-related group tariff. Data were presented according to BMI class for the normal weight, overweight and obese (total and grade I, II and III) cohorts for two time periods: at 1 year following the index date (1-year observation period) and at the time of data cut-off (31 December 2013). Underweight subjects were included for the prevalence analysis only. Costs were also analysed according to age (using a cut-off of 65 years).

Statistical analysis

To test the normality of data distribution, the skewness–kurtosis test was used. Continuous variables were reported as mean and SD or median and IQR, as appropriate, and compared with analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, whereas categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages, and compared with the χ2 test. Analyses were performed stratified for BMI groups. p≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata software V.12·0 (Stat Corp LP, College Station, Texas, USA), data management was carried out using Microsoft SQL Server 2012.

Results

Subjects

Overall, 20 159 adults were included in the study. Table 1 shows the characteristics of subjects who were classified as underweight, normal weight, overweight and obese at the index date. The prevalence of obesity was 22.2% (N=4471); of these, 3253 (72.8%) were classified as grade I obesity, 898 (20.1%) as grade II obesity and 320 (7.2%) as grade III obesity. The mean length of follow-up was 2.6, 2.7 and 2.8 years for the normal weight, overweight and obese groups, respectively (p=NS). Within the obese group, the mean length of follow-up was 2.8 years across each of the grade I, II and III obesity cohorts; 1.1% of subjects died at 1 year following the index date (normal weight 1.1%, overweight 1.2% and obese 1.1%; p=NS).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and demographics at the index date

| Weight |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under (BMI <18.5) | Normal (BMI ≥18.5 to <25) | Over (BMI ≥25 to <30) | Obese (BMI ≥30) | Total | |

| Patients, n (%) | 457 (2.3) | 7686 (38.1) | 7545 (37.4) | 4471 (22.2) | 20 159 (100) |

| Males:females, n:n | 67:390 | 2977:4709 | 3996:3549 | 2048:2423 | 9088:11 071 |

| Mean age±SD, years | 44.6±20.4* | 53.6±17.2† | 59.3±15.2‡ | 58.1±15.1 | 56.5±16.4 |

*p<0.001 vs normal weight, overweight and obese.

†p<0.001 vs overweight and obese.

‡p<0.001 vs obese.

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Prevalence of obesity by age

The proportion of subjects who were overweight or obese increased with age, while it decreased for normal weight subjects (p<0.001) (table 2). Among subjects aged >30 years, more than half were classified as overweight or obese (table 2). In particular, among subjects aged between 30 and 64 years, 36.4 and 22.8% were overweight and obese, respectively; among subjects aged 65+ years, 44.2 and 23.7% were overweight and obese, respectively (table 2).

Table 2.

Proportions of patients classified as being of normal weight, overweight and obese, stratified by age at the index date

| Prevalence | Normal weight | Overweight | Obese | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–29 years, n (%) | 743 (62.0)* | 267 (22.3)* | 189 (15.8)* | 1199 (100.0) |

| 30–64 years, n (%) | 4701 (40.8)† | 4195 (36.4)† | 2627 (22.8)† | 11 523 (100.0) |

| 65+ years, n (%) | 2242 (32.1) | 3083 (44.2) | 1655 (23.7) | 6980 (100.0) |

| Total | 7686 | 7545 | 4471 |

*p<0.0001 vs 30–64 years and +65 years.

†p<0.0001 vs +65 years.

Use of prescription medication

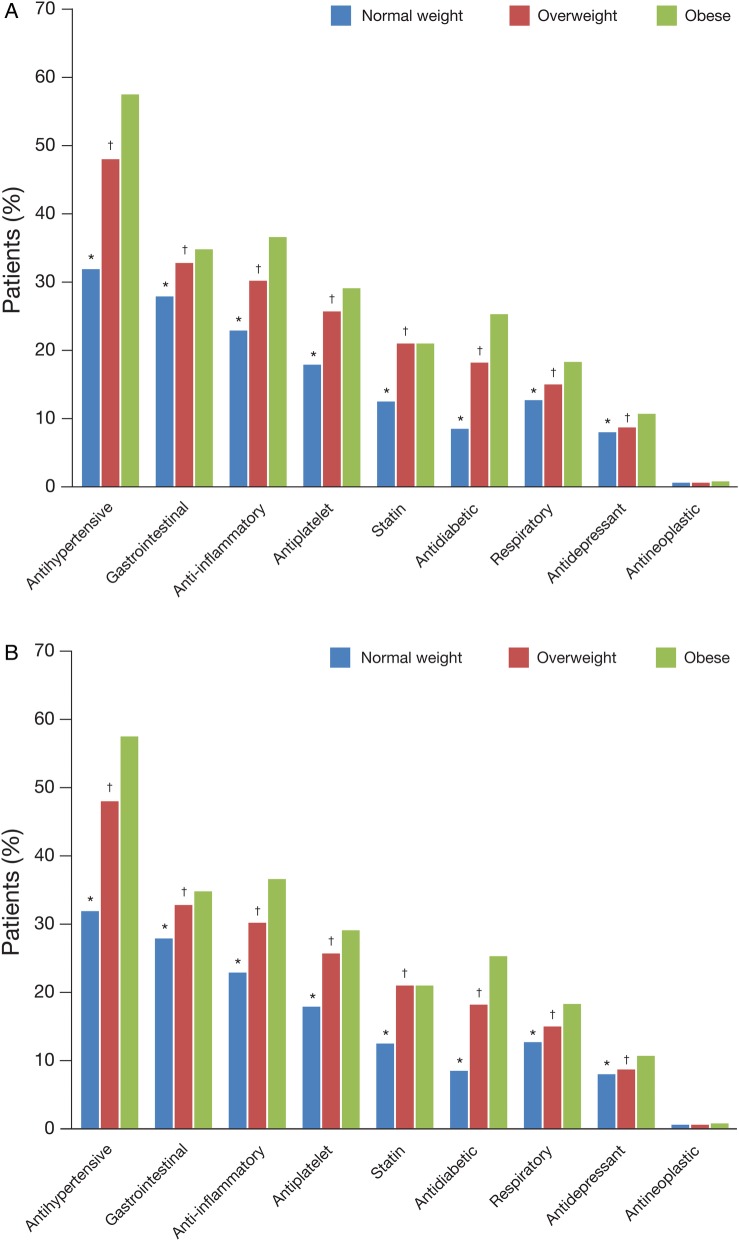

In total, 13 002 subjects from the normal weight, overweight and obese groups (66%) received at least one prescription drug treatment during the 1-year observation period. 3353 were obese subjects (75%), 4437 were normal weight subjects (57.7%) and 5212 were overweight subjects (69.1%). These differences were significant (p<0.0001 among groups); 14 807 (75.2%) subjects had received at least one drug treatment at data cut-off; 3666 were obese subjects (82%), 5276 were normal weight subjects (68.6%) and 5865 were overweight subjects (77.7%). Again, these differences were significant (p<0.0001 among groups). During the 1-year observation period, antihypertensive drugs were the most common drug class received (43.8% of subjects); 31.3% of subjects received gastrointestinal drugs, 28.8% received anti-inflammatory drugs, 23.4% received antiplatelet drugs, 17.7% received statins and 0.7% received antineoplastic drugs. Obese patients received each class of drug more frequently than normal weight or overweight subjects (p<0.001 for all drug classes except antineoplastic among all groups and statins between overweight and obese subjects (p=NS)) (figure 1A). The largest difference in drug use between subjects who were obese and of normal weight was observed for the antidiabetic drug class (30.1% increase in obese subjects; p<0.001). Results were similar for the period up to data cut-off (p<0.001 for all drug classes except antineoplastic among all groups and statins between overweight and obese subjects (p=NS)) (figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Patients exposed to treatment, by BMI category and drug class, during (A) the 1-year observation period and (B) the period up to data cut-off. (A) *p<0.001 vs overweight and obese subjects; †p<0.001 vs obese subjects. (B) *p<0.001 vs overweight and obese subjects; †p<0.001 vs obese subjects. BMI, body mass index.

Duration of hospitalisation

In total, 1416 subjects (7.2%) were hospitalised at least once during the 1-year observation period and this increased to 3204 subjects (16.3%) for the period up to data cut-off. In normal weight, overweight and obese subjects, hospitalisation rates were 6.5%, 7.7% and 7.6%, respectively, at 1 year, and 14.8%, 17.3% and 17.0%, respectively, at data cut-off. Obese and overweight subjects had a higher hospitalisation rate in comparison with normal weight individuals (p=0.006 and 0.03, at 1-year follow-up and data cut-off, respectively). In the 1-year observation period, the mean duration of hospitalisation was 3 (IQR 7) days in normal weight subjects, 4 (IQR 7) days in overweight subjects and 5 (IQR 8) days in obese subjects (p=NS). Within the group of obese subjects, median duration of hospitalisation was not different among the grade III (4.5 (IQR 8) days), grade I (5 IQR 8) days) and grade II obese (4.5 (IQR 9.5) days) groups. The most common reasons for hospitalisation in the grade I and II obese groups were type 2 diabetes and essential hypertension (not specified; 0.8% each). For grade III obese patients, the most common reasons for hospitalisation were severe obesity and benign essential hypertension (1.6% and 0.9%, respectively). Similarly, the median duration of hospitalisation for the period up to data cut-off did not show significant differences among groups (obese subjects, 5 (IQR 7) days; normal weight subjects, 3 (IQR 7) days and overweight subjects, 4 (IQR 7) days, respectively; p=NS), as well as among obese subgroups (grade I obesity 4 (IQR 7) days; grade II obesity 5 (IQR 9) days and grade III obesity 5 (IQR 7.5) days; p=NS).

Use of specialist services

During the 1-year observation period, an average of 5.3 (±7.0) specialist services were required overall for obese subjects; the mean number of specialist services required was higher in the grade II obese group (5.8±9.5) than in the other BMI groups (4.4±5.5, 5.0±7.2, 5.2±6.3 and 5.0±5.8 for normal weight, overweight, grade I obese and grade III obese groups, respectively, p<0.001). At the point of data cut-off, the mean number of specialist services required was 18.8 (±26.8) in the grade II obese group compared with 12.7 (±16.1), 15.8 (±21.3), 16.6 (±18.8) and 15.9 (±18.5) for the normal weight, overweight, grade I and III obese groups, respectively (p<0.001).

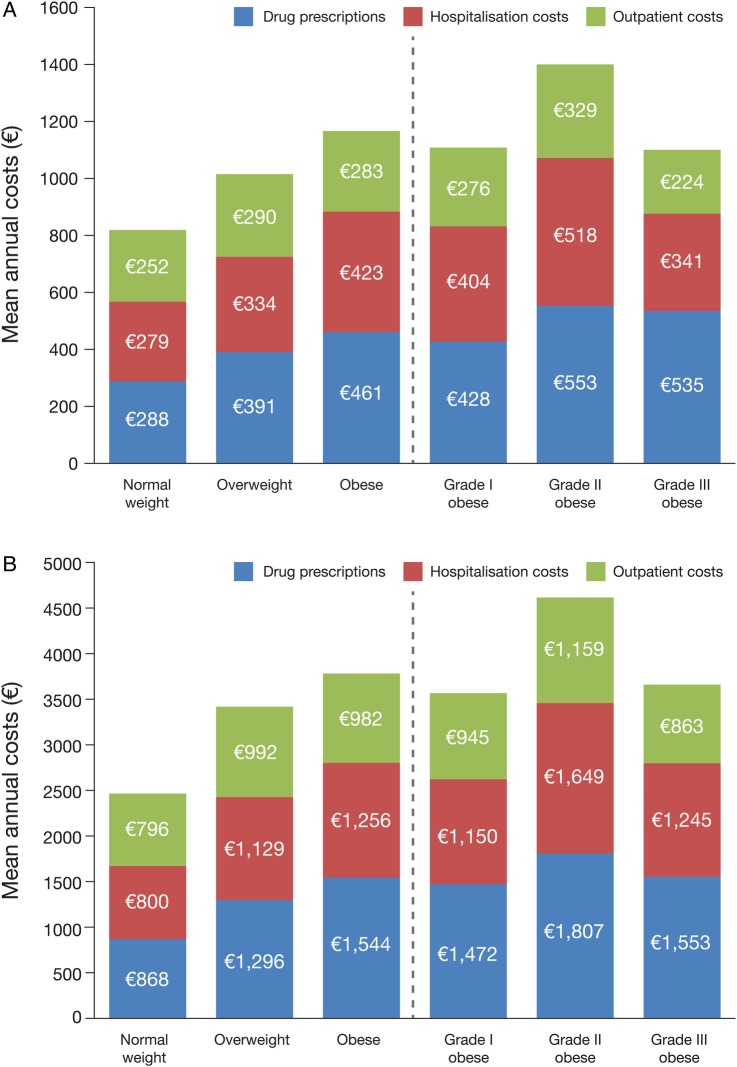

Costs

During the observation period, the mean annual healthcare costs per subject were €819.03 for the normal weight group, €1015.19 for the overweight group and €1166.52 for the obese group, respectively. The mean healthcare cost per subject for the period up to data cut-off was €2465.01 for the normal weight group, €3417.81 for the overweight group and €3782.21 for the obese group, respectively. Mean healthcare costs during the 1-year observation period were higher in obese than in non-obese subjects (p<0.001), while no differences were observed at data cut-off point (p=NS) (figure 2A, B). During the 1-year observation period, the highest mean annual costs per individual in the obese group were associated with drug prescriptions (€461), followed by hospitalisation costs (€423) and specialised outpatient services (€283). Subjects with grade II obesity generated higher costs than the grade I and grade III obese groups, primarily owing to higher hospitalisation costs (p<0.01). Compared with normal weight controls over 1 year, costs were higher by 23.5% for overweight subjects (34.3% when considering drug costs only), 34.8% for patients with grade I obesity (47.0% for drug costs only), 70.4% for those with grade II obesity (90.1% for drug costs only) and 33.9% for patients with grade III obesity (83.9% for drug costs only) (all values: p<0.01). At the point of data cut-off, the mean annual costs in the obese group had increased to €1544.24 for drug prescriptions, €1256.41 for hospitalisation costs and €981.56 for outpatient services (figure 2B). Similar to the 1-year observation, costs were higher for obese patients in comparison with normal weight controls (p<0.01) (figure 2B). Again, patients with grade II obesity generated higher costs, mainly due to outpatient costs (p<0.05) (figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Mean annual costs per surviving individual, by BMI category, during (A) the 1-year observation period and (B) the period up to data cut-off. (A) Overall costs: p<0.001 vs overweight and obese subjects; p<0.01 vs grade I and grade II obese subjects. Drug costs: p<0.001, p<0.01; Hospitalisation costs: p<0.01, p=NS; Outpatient costs: p<0.01, p=NS. (B) Overall costs: p<0.001 vs overweight and obese subjects; p<0.01 vs grade I and grade II obese subjects. Drug costs: p<0.001, p=NS; Hospitalisation costs: p<0.001, p=NS; Outpatient costs: p<0.001, p<0.05. BMI, body mass index.

The possible effect of age, when comparing the impact of obesity on healthcare costs, is reported in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Mean cost according to age and BMI. BMI, body mass index.

Discussion

There are still limited data on healthcare resources usage for untreated obesity and its economic impact on healthcare systems. We report here on the prevalence and associated costs of obesity in an Italian population of over 20 000 individuals. Our study represents one of the largest European population studies on obesity and provides a real-life assessment of the economic impact of this increasingly prevalent condition. The findings of our study show that obese adults who did not receive treatment for their underlying obesity used more prescription drugs, experienced longer durations of hospitalisation, required more specialised outpatient healthcare and were associated with substantially greater costs compared with normal weight adults.

Our study directly evaluated the economic impact of comorbidities associated with obesity on the Italian healthcare system by integrating multiple data sources, taking into account the true costs of pharmaceutical treatments, the use of diagnostic and specialist services and hospitalisations over a period of up to 5 years. Importantly, as a result of the structure of the Italian NHS and the multiple data sources available, the healthcare resources and costs reported in this study are a true and accurate reflection of the real-life costs for each subject. To the best of our knowledge, at present only few studies have evaluated data on real-life healthcare costs from obesity associated with BMI.11–13 Previous studies have been limited by the fact that they were based on resources used at a single point in time or restricted to a single hospital department. Our study in a real-world setting helps to identify the actual consumption of resources by obese patients. However, as with any retrospective observational study, it should be noted that limitations might exist as a result of the variability of professional practice and information bias.

Obese subjects used a wide range of drugs, including antihypertensive, gastrointestinal, anti-inflammatory, antiplatelet and antidiabetic drugs. Our study showed that obese subjects generally received each class of drug more frequently than normal weight or overweight subjects, with the exception of antidepressants. This is likely to reflect the various comorbidities that obese subjects commonly experience if their underlying condition remains untreated, such as diabetes and hypertension. Notably, antidiabetic and antihypertensive drugs were used in around twice as many obese as normal weight subjects. Overall healthcare costs were substantially higher for obese than for non-obese individuals. Prescriptions represented the greatest overall costs, highlighting the economic impact that obesity-related comorbidities have on healthcare systems.

There were also significant costs associated with hospitalisation, particularly for the grade II obese group; this may be related to the longer mean duration of hospitalisation in these patients compared with grade III obese and non-obese subjects. The relatively short hospital stay observed in the grade III obesity group should be highlighted as this may suggest that many institutions within the Italian healthcare system are not adequately equipped to diagnose and treat morbidly obese subjects, such as radiological instruments not being suitable to host severely obese patients, or a lack of specialists with sufficient experience to prescribe suitable therapies to address the different comorbidities. This could result in these patients being discharged from hospital earlier than should be expected. It is also possible that, as severely obese people are frequently depressed,14–16 they may refuse to leave home to go to hospital at all, unless they have an acute condition.

The prevalence of obesity reported in this study (22·2%) is in line with the current WHO estimation of the prevalence of obesity in Italy (21·0%),3 but higher than other estimates (∼10%).17 18 The proportion of subjects who were overweight or obese increased with age, with more than half of adults aged ≥30 years being overweight or obese. Similar findings have previously been reported in Italy;19 based on data from five surveys conducted between 2006 and 2010, the prevalence ratios for overweight/obesity in individuals aged ≥65 vs 18–24 years were 2·01 in men and 2·65 in women.17 These data suggest that it may be important to target and educate individuals who are overweight or have grade I obesity and are of working age, with the aim of preventing them from becoming more obese later in life.

Since older subjects are likely to consume more healthcare resources, we have also analysed the possible effect of age when comparing the impact of obesity on healthcare costs. The results highlight that healthcare costs did not increase just because obese patients were older than normal weight patients, but that in each age group, the costs of obese patients were higher than other patients.

It is important to raise awareness that the direct treatment of patients who are severely obese would help to reduce the economic impact of the condition on healthcare systems.20 The initial costs associated with treatment, such as bariatric surgery, would probably be offset by the subsequent savings made on drug prescriptions, hospitalisation costs and outpatient care related to the treatment of comorbidities.21 22 Indeed, a recent meta-analysis, comprising 37 720 patients across 11 studies, showed that bariatric surgery significantly reduces drug use and costs.23 In addition, the direct treatment of obesity would likely help to reduce the burden on physicians who spend a substantial amount of time treating the comorbidities associated with obesity. The value of preventative strategies for obesity is an important consideration for decision makers, particularly given the increasing concern over the sustainability of the healthcare system and the ageing population. Measures such as advocating the value of a healthy and balanced diet with regular exercise as part of an early obesity prevention strategy are likely to be important.

Although in our study we used the healthcare databases of Lombardy, Tuscany and Campania, three Italian regions localised from north to south of Italy, including data for a total population of about 2.3 million, and the Health Search Database of the Società Italiana di Medicina Generale, larger studies are needed to confirm and to enhance the generalisability of the findings.

In conclusion, our data highlight the need to develop public health policies that aim to prevent the development of obesity at an early age and also to proactively and effectively treat severely obese patients, thereby reducing the overall economic burden of this condition.

Acknowledgments

We thank Vito Basile, Chairman of Burson-Marsteller Italy, for his commitment in the design of the project and for his assistance. We also thank Andrew Jones, PhD, from Mudskipper Business Ltd, for medical editorial assistance with this manuscript. Special thanks are given to the general practitioners (Medico di Medicina Generale (MMG)) and the three Italian local health authorities (ASL) for making available the data analysed in the study: ASL Napoli 1 ASL: Dott. Antonio Stellato. MMG: Enrico Benedetto, Giovanni Paudice, Antonio Mura, Vincenzo Piramide, Salvatore Scapolatello, Antonio Ambrosanio, Mario Avano, Irene Caruso, Giuseppe Crispano, Eliseo De Leo, Emilia De Simone, Salvatore Falanga, Giovanni Ferrara, Pasquale Festa, Massimo Maddaloni, Giovanni Mansueto, Pasqualino Mastromo, Francesco Carmine Miniello, Giovanni Piccolo Raffaele Napoli, Franco Schiano and Angela Zappa. ASL Grosseto ASL: Dott. Fabio Lena. MMG: Alessio Bonadonna, Massimo Olivoni, Franca Castellani, Gino Maestrini, Valeria Rombai, Laura Bellangioli, Gabriele Guidoni, Giancarlo Vitillo, Tommaso Iocca, Anna Pia Capperucci, Luca Pianelli, Ugo Simoni, Sandro Monaci, Marilena Del Santo, Andrea Salvetti, Giuseppe Virgili, Rolando Zullo and Nicola Briganti. ASL Bergamo ASL: Dott. Marco Gambera. MMG: Elio Pinotti, Giuliana Giunti, Paola Fausta Tagliabue, Monica Rovelli, Francesca Marchesi, Alessandro Filippi, Marino Zappa, Anna Scorpiniti, Alex Fulgosi, Manuela Mariuz, Luca Benedetti, Lina Magrì, Angela Milesi, Pierrentao Pernici, Annamaria Cremaschi, Paola Bocchi, Mahmoud Mazid, Luigi Donzelli, Fulvio Patelli, Lucilla Luderin, Giovanni Argenti, Alfredo Di Landro, Carmela Neotti and Sergio Nicoli

Footnotes

Contributors: CV, VB and LDE contributed to the design and conduct of the study, data collection and management, analysis and interpretation of the data and preparation of the manuscript. AC, ML, MD'A, SS, EF and PS contributed to clinical evaluation and data interpretation and investigated all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: Unrestricted financial support for the collection of data and for medical editorial assistance was provided by Johnson & Johnson Medical.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Not required for this study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight: fact sheet N°311 2015. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/.

- 2.Fruhbeck G, Toplak H, Woodward E et al. Obesity: the gateway to ill health—an EASO position statement on a rising public health, clinical and scientific challenge in Europe. Obes Facts 2013;6:117–20. 10.1159/000350627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. Global Health Observatory Data Repository. Obesity, data by country 2015. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.A900A?lang=en

- 4.Peltzer K, Pengpid S, Samuels TA et al. Prevalence of overweight/obesity and its associated factors among university students from 22 countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014;11:7425–41. 10.3390/ijerph110707425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Specchia ML, Veneziano MA, Cadeddu C et al. Economic impact of adult obesity on health systems: a systematic review. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:255–62. 10.1093/eurpub/cku170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelone F, Specchia ML, Veneziano MA et al. Economic impact of childhood obesity on health systems: a systematic review. Obes Rev 2012;13:431–40. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00968.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Migliore E, Pagano E, Mirabelli D et al. Hospitalization rates and cost in severe or complicated obesity: an Italian cohort study. BMC Public Health 2013;13:544 10.1186/1471-2458-13-544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degli Esposti E, Sturani A, Valpiani G et al. The relationship between body weight and drug costs: an Italian population-based study. Clin Ther 2006;28:1472–81. 10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.2016. Center for Disease Control, Atlanta, GA. Healthy weight. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/

- 10.Italian Medicines Agency. Guideline for the classification and conduction of the observational studies on medicines 2010. https://www.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/ricclin/sites/default/files/files_wysiwyg/files/CIRCULARS/Circular%2031st%20May%202010.pdf

- 11.Hammond RA, Levine R. The economic impact of obesity in the United States. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2010;3: 285–95. 10.2147/DMSOTT.S7384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuriyama S, Tsuji I, Ohkubo T et al. Medical care expenditure associated with body mass index in Japan: the Ohsaki Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2002;26:1069–74. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudisill C, Charlton J, Booth HP et al. Are healthcare costs from obesity associated with body mass index, comorbidity or depression? Cohort study using electronic health records. Clin Obes 2016;6:225–31. 10.1111/cob.12144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carey M, Small H, Yoong SL et al. Prevalence of comorbid depression and obesity in general practice: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64:e122–7. 10.3399/bjgp14X677482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lojko D, Buzuk G, Owecki M et al. Atypical features in depression: association with obesity and bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2015;185:76–80. 10.1016/j.jad.2015.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin-Rodriguez E, Guillen-Grima F, Marti A et al. Comorbidity associated with obesity in a large population: the APNA study. Obes Res Clin Pract 2015;9:435–47. 10.1016/j.orcp.2015.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallus S, Odone A, Lugo A et al. Overweight and obesity prevalence and determinants in Italy: an update to 2010. Eur J Nutr 2013;52:677–85. 10.1007/s00394-012-0372-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Obesity and the economics of prevention: fit not fat. Italy, update 2014 2014. http://www.oecd.org/italy/Obesity-Update-2014-ITALY.pdf

- 19.Binkin N, Fontana G, Lamberti A et al. A national survey of the prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity in Italy. Obes Rev 2010;11:2–10. 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00650.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.International Diabetes Federation (IDF). Global Diabetes Plan 2011–2021 2011. http://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/Global_Diabetes_Plan_Final.pdf

- 21.Picot J, Jones J, Colquitt JL et al. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bariatric (weight loss) surgery for obesity: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2009;13:1–357, iii 10.3310/hta13410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Picot J, Jones J, Colquitt JL et al. Weight loss surgery for mild to moderate obesity: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Obes Surg 2012;22:1496–506. 10.1007/s11695-012-0679-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopes EC, Heineck I, Athaydes G et al. Is bariatric surgery effective in reducing comorbidities and drug costs? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2015;25:1741–9. 10.1007/s11695-015-1777-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]