Abstract

Purpose

Leading health systems have invested in substantial quality improvement (QI) capacity building, but little is known about the aggregate effect of these investments at the health system level. We conducted a systematic review to identify key steps and elements that should be considered for system-level evaluations of investment in QI capacity building.

Methods

We searched for evaluations of QI capacity building and evaluations of QI training programmes. We included the most relevant indexed databases in the field and a strategic search of the grey literature. The latter included direct electronic scanning of 85 relevant government and institutional websites internationally. Data were extracted regarding evaluation design and common assessment themes and components.

Results

48 articles met the inclusion criteria. 46 articles described initiative-level non-economic evaluations of QI capacity building/training, while 2 studies included economic evaluations of QI capacity building/training, also at the initiative level. No system-level QI capacity building/training evaluations were found. We identified 17 evaluation components that fit within 5 overarching dimensions (characteristics of QI training; characteristics of QI activity; individual capacity; organisational capacity and impact) that should be considered in evaluations of QI capacity building. 8 key steps in return-on-investment (ROI) assessments in QI capacity building were identified: (1) planning—stakeholder perspective; (2) planning—temporal perspective; (3) identifying costs; (4) identifying benefits; (5) identifying intangible benefits that will not be included in the ROI estimation; (6) discerning attribution; (7) ROI calculations; (8) sensitivity analysis.

Conclusions

The literature on QI capacity building evaluation is limited in the number and scope of studies. Our findings, summarised in a Framework to Guide Evaluations of QI Capacity Building, can be used to start closing this knowledge gap.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review represents a pioneering attempt to identify efforts to evaluate quality improvement (QI) capacity building at the healthcare system level.

With the limited base of past work to draw on, we lack a shared or sufficiently broad vision of how to construct and evaluate QI capacity building efforts, and we have therefore little evidence to make judgements regarding the appropriateness of the articles identified.

The review contributes a synthesis of current practices for evaluating QI capacity building efforts and represents a starting point to help close the knowledge gap at the healthcare system level.

Introduction

Evidence over the past few decades has consistently demonstrated that low-quality care places a heavy financial and human burden on healthcare systems worldwide.1 2 The problem persists despite the fact that more organisations than ever before are actively engaged in quality improvement (QI) efforts.3 4

QI can be defined as a systematic approach to making changes that lead to better patient outcomes, stronger system performance and enhanced professional development. Improving healthcare quality requires active participation and interdisciplinary collaboration of a workforce skilled in QI, complemented by patients, families, academics and policymakers.5–7 However, evidence shows that healthcare professionals are often ill-prepared to promote QI efforts and reluctant to change.8 9 This gap may partly explain why QI activity does not reliably improve performance.10 11

A systematic approach to capacity/capability building for improvement has been identified as one of the key characteristics of healthcare systems that deliver high performance in cost and quality.12–14 QI capacity building increases the self-sustaining ability of organisations and systems to recognise, analyse and improve quality issues by controlling and allocating available resources more effectively.15 16 For the purpose of this study, we defined ‘QI capacity building’ as the planned development of knowledge, skills and other capabilities of a system or an organisation to improve quality.17 Following Bevan's12 definition, ‘capacity’ refers to having the right number and level of people who are actively engaged and able to conduct improvement, while ‘capability’ refers to the confidence, knowledge and skills to lead the improvement. Although we refer to capacity building throughout this article, our focus is inclusive of capacity and capability.

Even though substantial investments in healthcare quality have focused on building capacity, there is a significant research gap in terms of assessment of these efforts. In addition, numerous research studies have evaluated specific QI initiatives and programmes, but little is known about the impact of QI capacity at the healthcare system level.7 18 By system level, we mean the governance, leadership, resources and service delivery arrangements that together enable a health system (encompassing healthcare providers, managers and other stakeholders) to design, implement and evaluate QI activities. This ‘system-level’ definition includes national or subnational systems (such as state, provincial or regional systems depending on the jurisdiction) and can represent autonomous healthcare systems serving specific populations (such as military services) or larger healthcare organisations that provide a range of services to specified but geographically dispersed populations (eg, Kaiser Permanente).

Capacity building assessments have been largely restricted to evaluations of specific training programmes,7 rather than system-wide studies. As Shortell et al19 noted, part of the difficulty of assessing the impact of QI activity and investments1 lies in the fact that most studies focus on a single site of care, condition or process that represents only one particular organisational problem. In healthcare, the costs of poor quality and the benefits of improved care are spread among multiple stakeholders and settings, yet organisational initiatives often focus on short-term results that are within the exclusive control of a single organisation.20 Furthermore, while building QI capacity has been a key component of system transformation efforts, it generally coexists with other capacity building activities, such as leadership training and professional development, making it hard to separate out and to assess the importance of QI capacity investments. In the current context, little is known about how QI capacity can be produced most effectively and efficiently from a system-level perspective.

While there are a number of approaches for evaluating efforts in QI capacity building and training,21–23 we sought system-level economic evaluations to understand the impact of capacity building efforts on health-system performance and the associated return on investment (ROI). ROI is a simple expression of economic evaluation that is intuitive and effective in allowing estimations of the value generated from healthcare investments. The use of ROI in QI allows the comparison of multiple inputs of an intervention on a common metric (cost). By monetising benefits (better care and better health), the intervention's value can be calculated relative to cost,24 complying with broadly accepted ‘value’ frameworks, such as the Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Triple Aim.25

The purpose of this study was to identify key steps and elements that should be considered for system-level evaluations of investment in QI capacity building, summarised in a framework that can be used to guide such evaluations. Accordingly, we conducted a systematic review of the healthcare services and policy literature with the following three objectives: first, to identify system-level evaluations of QI capacity building/training; second, to identify existing evaluations of the investment in QI capacity building/training (ROI or other types of economic evaluation), even if these were at a programme or initiative level, rather than the system level; and third, to identify any other evaluations or analyses of QI capacity building that would address the purpose of our study.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the healthcare services and policy literature to identify two types of studies: (1) evaluations of QI capacity building; and (2) evaluations of QI training programmes. The search included the most relevant indexed databases in the field and a targeted search of the grey literature.

The following eight indexed databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Social Work Abstracts, HealthSTAR, Health and Psychosocial Instruments, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Social Sciences Abstracts and Scopus. We used the following search terms: Quality Improvement/Assurance and Capacity Building/Assessment/Evaluation or Training Assessment/Evaluation. We included the term quality assurance (QA) to ensure that no relevant articles were missed due to imprecise index term use. The full search strategy for EMBASE is provided in online supplementary appendix 1. Given the nature of our search, we anticipated that a substantial proportion of relevant articles would not be captured by indexed sources. Therefore, an extensive grey literature search was conducted, which included: Google Scholar; direct scanning of relevant government and institutional websites; reference searches of identified articles and additional targeted searches based on research team input. The search terms used for Google Scholar were combinations of the same terms used for indexed databases, in addition to ‘healthcare/health care’. Our scan of institutional websites included 85 organisations in Canada, the USA, the UK, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and organisations with an international mandate (full list available). All searches were completed between November 2014 and January 2015. A study investigator (GM) supported by a Research Assistant (JI) conducted all searches, screening and data extraction.

bmjopen-2016-012431supp_appendix.pdf (206KB, pdf)

Identified articles were screened based on their title and abstract. The 143 articles identified through MEDLINE were double screened at the beginning of this process to ensure inter-rater reliability (94% agreement). This was followed by regular meetings to monitor screening criteria. All articles describing the following types of study were identified for retrieval of full-text articles: QI/QA assessments/evaluations; QI/QA training assessments/evaluations and QI/QA capacity building initiatives. All full-text articles retrieved were then double screened, applying the following exclusion criteria: QI/QA initiatives or training without an assessment or evaluation; assessments or evaluations of QI/QA initiatives not primarily focused on QI/QA capacity building; and training in areas other than QI/QA (eg, training in clinical skills). Only articles written in English were included, with no restrictions on publication date or type. Data extracted from the selected articles included study type, context, evaluation design, common assessment themes and components.

Results

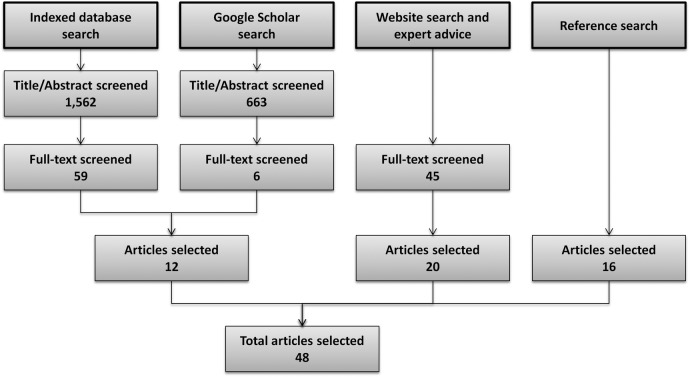

A total of 1562 references were initially identified through indexed databases and an additional 663 through Google Scholar. After title/abstract screening, 65 articles were retrieved for full-text screening. Forty-five additional articles were identified through institutional website scanning and recommendations from the research team. A total of 110 full-text articles were screened, and a further 16 articles were identified through reference list searches. Ultimately, 48 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study. Figure 1 presents a flow chart summarising this process.

Figure 1.

Searching and screening process and number of articles identified.

Table 1 pairs our research objectives with the number of articles identified, and shows general characteristics of the 48 articles selected. We did not identify any system-level QI capacity building/training evaluations (ie, evaluations targeting efforts that have broad system-wide, cross-sectoral, multiprofessional focus). All evaluations identified in our search had narrower foci on specific initiatives within particular sectors, professions or programmes. Two studies included economic evaluations of QI capacity building/training, specifically evaluations of ROI, which coincided with our second research objective. Forty-six articles representing other evaluations or analyses of QI initiatives or training were identified in relation to our third research objective. A synthesis of this general evidence is presented next.

Table 1.

General characteristics of studies included

| Objective |

Number | Country | Number | Level of capacity | Number | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | System-level evaluations (economic or not) of QI capacity building/training | 0 | ||||

| 2 | Initiative level economic evaluations of QI capacity building/training | 2 | USA | 1 | Organisational | 2 |

| UK | 1 | |||||

| 3 | Initiative level evaluations (non-economic) of QI capacity building/training | 46 | USA | 33 | Individual | 19 |

| Canada | 8 | Organisational | 11 | |||

| - Evaluations of QI training programme | (19) | UK | 3 | Interorganisational | 16 | |

| - Evaluations of QI capacity building programme/initiative | (6) | Ethiopia | 1 | |||

| - QI capacity evaluations | (5) | Uganda | 1 | |||

| - Assessment or analysis-related to QI capacity building | (16) | |||||

General evidence on QI capacity building evaluation

As shown in table 1, only 30 articles represented studies directly evaluating QI capacity, QI capacity building initiatives or QI training. The other 16 articles were assessments or analyses related to QI capacity building, but not direct evaluations of it (eg, inclusion of QI in curriculum guidelines for healthcare professional education or accreditation, description of QI training programmes, analysis of how to build and evaluate QI capacity). Table 2 summarises the main content of the 46 initiative-level (non-economic) evaluations included.

Table 2.

Findings from included articles, organised by theme

| Numbers in brackets categorize findings through thematic grouping, according to the following 17 evaluation components and five overarching dimensions. |

Characteristics of QI training

|

Characteristics of QI activity

|

Individual capacity (enablers/barriers)

|

Organisational capacity (enablers/barriers):

|

Impact (outcomes)

|

Continued

| Characteristics of QI training | Characteristics of QI activity | Individual capacity (enablers/barriers) | Organisational capacity (enablers/barriers) | Impact (outcomes) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluations of QI training programme | |||||

| Cornett et al26 | Experiential learning through QI intervention (1). Use of coaching (2) and distance learning (3) | QI training at the working site (6). QI coaching from trainees to others in the organisation (7) | Confidence to conduct QI activities (9) | Achievement of project goals, as measurable outcomes or processes (17) | |

| Davis et al27 | Webcast participants had high receptivity to QI training (3) | Receptivity to learning about and implementing QI activities (10) | |||

| Riley et al28 | QI project as part of QI training (1). Full distance learning (3). Programme developed in partnership (4) | QI training at the working site (6) | Kirkpatrick model,21 including ‘learning’ and ‘behaviour’ (9). QI programme relevance rating (10). Self-efficacy and willingness to conduct a future QI project (9) | Management support (12) and availability of resources (13) | Project outcome metrics (17) |

| Ruud et al29 | QI project as part of QI training (1). Programme developed in partnership (4) | Transfer of knowledge and skills gained back to the work setting (7) | Kirkpatrick model,21 including ‘learning’ and ‘behaviour’ (9) | ||

| Ng and Trimnell30 | QI project as part of QI training (1). Coaching and mentorship as part of QI training (2) | Assessment of the spread of QI knowledge (7) | Kirkpatrick model,21 including ‘learning’ and ‘behaviour’ (9) | Meeting patient outcomes targeted by QI projects (17) | |

| Daugherty et al31 (Emory Healthcare) | QI project as part of QI training (1). Coaching and mentorship from previously trained staff (2). Programme developed in partnership (4) | QI training at the working site (6) | Support from supervisor and from senior leadership and ongoing institutional support (12). Improved teamwork (13). Barriers included financial resources (Rask et al) (13) | Participant perception of impact on processes and outcomes, including patient satisfaction, access or safety (17) | |

| Rask et al32 (Emory Healthcare) | Ability in the use of data (9) | ||||

| Blake et al33 (Emory Healthcare) | Confidence to train others (9) | ||||

| Lavigne34 | QI training in pharmacy curriculum (5) | Assessed motivation, importance, usefulness, awareness impact on patient health (10). Self-reported ability to identify quality issues and knowledge of and ability to implement QI methods (9) | |||

| Warholak et al35 | QI training during pharmacy education (5) | ||||

| Diaz et al36 | Impact after QI training during family medicine residency (5) | QI training during residency increases subsequent family physician QI involvement (10) | |||

| Canal et al37 | QI project as part of QI training (1). QI training during surgery residency (5) | QI training at the working site (6) | Self-assessed QI efficacy (9) | Sponsorship and involvement from team leaders on improvement initiatives (13) | |

| Djuricich et al38 | QI project as part of QI training (1). QI training during internal medicine and paediatric residency (5) | QI training at the working site (6) | Self-assessed QI efficacy (9). Interest scale (10) | ||

| Ogrinc et al39 | QI project as part of QI training (1). PBLI training during internal medicine residency (5) | QI training at the working site (6) | Self-assessed confidence and proficiency in PBLI (9) | Sponsorship and involvement from team leaders of improvement initiatives (13) | |

| Didic et al40 | Assessment of training programme directed at board member and executive leaders of healthcare organisations. Includes questions on board relationship with CEO and clinical leadership, culture, information and measurement (12) | ||||

| Robert Wood Johnson Foundation7 | Training must be experiential (1). Importance of QI in clinical curricula (5) | Importance of QI coaches and mentor at the organisation (7) | Cost of QI training as barrier (11) | Key enablers: organisational support (12), infrastructure for QI and effective incentives (13) | |

| Robert Wood Johnson Foundation41 | Importance of opportunities to apply new skills (6) | Key enablers: organisational culture, leadership support and clear sponsorship of QI projects (12) | |||

| Morganti et al42 | Training reinforcement and coaching (7). Measures of QI training dosage included informal coaching (7). Patient-centred QI, involvement of family and friends at all levels (8) | Understanding of QI principles and ability to apply QI skills (9). Importance of QI training (10) | Organisational culture of QI and excellence, and leadership involvement (12). Team empowerment and financial resources; team effectiveness; end-user involvement (13). Information technology systems; performance monitoring (14) and diffusion (15) | QI progress achieved in interventions following the QI training programme, using outcomes variables from the organisations (Kirkpatrick l4: ‘results’21) (17) | |

| Morganti et al43 | |||||

| Evaluations of QI capacity building programmes/initiatives | |||||

| Stover et al44 | QI coaching from supervisors (2). Partnership between the Ministry of Health, international and local universities, and research and training institutes (4) | Involvement of community stakeholders (8) | Self-assessed capacity for improvement work (9). Motivation for participation in improvement work: deaths, achieving health goals and positive experience with QI (10) | Perception of district culture and leadership commitment and support for QI (12). Local team empowerment (13). Use of QI data; results-oriented accountability (14) and diffusion across teams (15) | |

| Matovu et al45 | QI project as part of QI training (1). Coaching and mentorship as part of QI training (2). In collaboration with local university (4) | QI training at the working site (6) | |||

| Runnacles et al46 | QI project as part of QI training (1). Coaching and mentorship as part of QI training (2). Programme directed at physicians during residency (5) | QI training at the working site (6) | Organisational culture receptive to change, senior executive support, and engagement of operational and improvement managers (12) | ||

| Adler et al3 | Inhospital QI training (4). Efforts to integrate QI training into medical education (5) | Participatory from top and lower management to physicians (12). Key QI capability factors: teamwork, communication, specialised QI staff and committees and HR management (13). Information infrastructure, performance measurement, oversight and accountability (14); incentives to cross-unit collaboration (15). QI strategic priority (16) | |||

| Davis et al47 | Barriers to QI: lack of time, resources, perceived low relevance, poor leadership and teamwork commitment to QI, and insufficient QI training and experience (11). Mandatory QI for accreditation may be a QI driver (10) | Leadership support (12). Number of staff trained in QI and regular contact between teams and decision-makers (13). Data collection and monitoring (14). National QI initiative (16) | |||

| Health Quality Ontario48 (Learning Community programme) | QI coaching is a key element of this improvement programme (2). Virtual workspace and knowledge sharing (3) | QI training at the working site (6) | Motivation included positive past experience with QI, example from other organisations, need to meet specific improvement goals and external pressures (10) | ||

| QI capacity evaluations | |||||

| Weiner et al49 | Extent of organisational deployment; senior management (12), hospital staff and physician participation (13). Diffusion across units (15) | Hospital level outcomes quality measures (17) | |||

| Gagliardi et al50 | Education and training as key QI role (7) | Role of accreditation as a QI driver (10) | Senior management and board involvement, fostering QI culture (12). Communication and teamwork (13). Data analysis and monitoring (14). Strategic planning (16) | Adverse events and patient satisfaction (17) | |

| Ontario Hospital Association51 | Frequent partnership to develop QI plans (4). | Growing involvement of patient and community in QI (8) | Insufficient opportunities for formally training staff in QI (11) | Leadership involvement in QI (12) | |

| British Columbia Patient Safety and Quality Council52 | Distance learning to increase QI training feasibility (3) | Importance of QI training and coaching at work and through personal study (7) | Tuition fees as a barrier to QI training (11) | Support of their organisations is critical for QI trainees (12) | |

| Lawrence and Tomolo53 | Assessment tool for QI during medical education (5) | Self-efficacy in QI plan development and implementation, developing a data collection plan, and teaching QI principles (9) | |||

| Assessment or analysis related to QI capacity building | |||||

| Batalden et al54 | Practice-based learning and improvement (PBLI) as one of six general competencies of graduate medical education (5) | ||||

| Butterworth et al55 | Undergraduate QI training for nurses and doctors (5) | ||||

| Headrick et al56 | Use of web-based resources (3). Partnership between IHI, universities and healthcare organisations (4). Interprofessional QI training for undergraduate nurses and doctors (5) | Focus on application in care setting (6) | Evaluation on knowledge and skills (9); and perceived importance of QI (10) | Focus on interprofessional communications and teamwork (13) | Minimal though recognised importance of evaluating changes in behaviour and outcomes (17) |

| American Academy of Family Physicians57 | Family medicine resident should have knowledge in specific QI tools (5) | Family medicine resident should have hands-on experience leading performance improvement initiatives (6) | |||

| Saskatchewan Health Quality Council58 | Lectures in QI to students in various health science programmes (5) | ||||

| Hutchison et al59 | Partnership with provincial medical associations for QI training in primary care (4) | Performance measurement (17) | |||

| Farley et al60 | Integration of patient perspective into QI (8) | ||||

| Headrick et al61 | QI training for medical students (5) | Learners engaging in care and improvement (6). Health professionals engaged in and teaching QI (7). Patient and family engagement (8) | Leadership involvement in QI (12). Data transforming into useful information (14) | ||

| American Association of Colleges of Nursing62 | Knowledge and skills in leadership, quality improvement and patient safety among nursing educational standards (5) | Effective working relationships and open communication and cooperation within the interdisciplinary team; use of information and communication technologies to enhance care and improve outcomes (13). Employ data for QI and safety (14) | Use performance methods to assess and improve outcomes (17) | ||

| Cronenwett et al63 (Quality and Safety Education for Nurses (QSEN)) | QI competency should be developed during prelicensure nursing education (5) | QI competency skill on seeking information about QI projects (6) | QI competency requires skills on the use of QI methods, tools and quality measurement (9) | QI competency requires knowledge and skills on reviewing and improving outcomes of care (17). | |

| Cronenwett et al64 (QSEN) | QSEN competencies are appropriate for advance practice nurses, including QI (5) | ||||

| Batalden and Davidoff5 | Domains of QI interest include knowledge of customer/beneficiary and the social context (8). Knowledge of particular contexts is involved in QI (6) | Knowledge on improvement methods (9) | Domains of QI interest include leading and following, collaboration (13); measurement, variation and accountability (14). Strategy as driver of change is involved in QI (16) | Performance measurement to assess the effect of changes (17) | |

| Bevan12 | Capability building needs to be ‘hard-wired’ into the practice (6). Train initially those who can spread the skills most widely (7). Enable service users to drive and influence change (8) | Importance of assessing knowledge and skills in improvement (9) and interest (10). Performance management should include incentives (10). Insufficient time as barrier (11) | Key elements highlighted relate to culture and leadership support (12); teamwork and human resources management (13); measurement, use of evidence and benchmarks (14). Capability building strategies (16) need to take account of how change spreads in complex adaptive systems (15) | Connect skill building to results and realising benefits. Importance of evidence from economic assessments (17) | |

| Batalden et al65 (Veterans Administration National Quality Scholars (VAQS)) | Mentoring is a critical part of the programme (2). Use of distance learning technologies (3). Collaborative programme between universities and VA care sites (4) | Most important venues for learning are the programme sites themselves (6). Physicians trained by this programme should be able to teach QI (7) | |||

| Splaine et al66 67 (VAQS) | Curriculum domains include: leading and following, collaboration (13); measurement, variation and accountability (14) | ||||

| Curriculum knowledge domains include customer/beneficiary knowledge and social context (8) | |||||

Merged cells indicate that the same content was included in more than one related article.

We identified wide variation in the approach and measures used to evaluate QI capacity and programmes or initiatives to build QI capacity. While evaluations of QI training programmes are mostly focused on measuring the incremental improvement in participant QI knowledge and skills, broader evaluations of QI capacity or capacity building initiatives are mainly focused on organisational enablers and barriers, although this pattern is inconsistent. It is worth highlighting that only 9 (30%) of the 30 direct QI evaluations identified assessed the impact of QI capacity/training in terms of patient or programme outcomes (table 2).

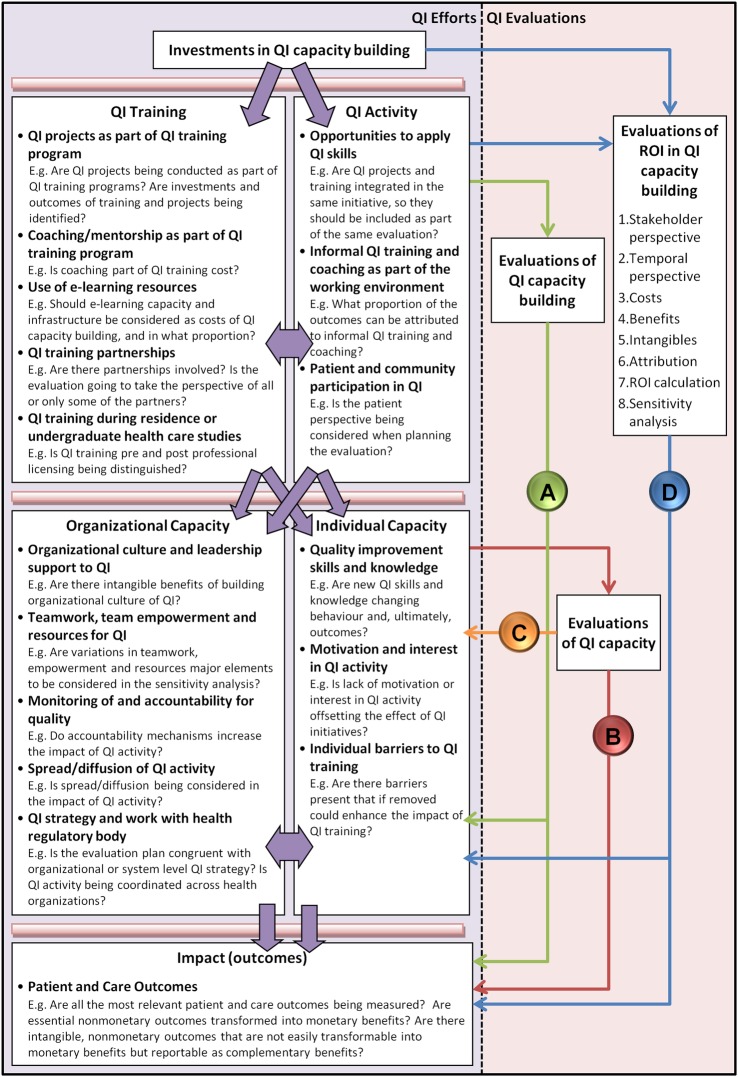

The process of identifying the evaluation components started with the identification of all components evaluated in the 46 articles, which were grouped according to common themes. Given the diversity of approaches, we identified 17 evaluation components that fit into 5 overarching dimensions, which are presented in table 2 and figure 2. These dimensions and components should be considered for inclusion in QI capacity building evaluations, and eventually adapted to system-level QI capacity building evaluations. Figure 2 also provides examples of how these evaluation components can be used.

Figure 2.

Framework to guide evaluations of quality improvement capacity building.

Evaluations of ROI in QI initiatives

Given the limited evidence, we paid special attention to evaluations of ROI in QI initiatives that could inform our study objectives. We used Phillips' ROI Model in Training and Performance Improvement Programs,68 a commonly referenced work in this discipline, to analyse the alignment with the two studies that evaluated ROI in QI initiatives. Table 3 compares the approaches used in these studies and identifies elements used to calculate ROI specifically in QI capacity building initiatives.

Table 3.

Alignment of return on investment in quality improvement capacity building assessments

| Phillips’ ROI in Training and Improvement Model68 | The Productive Ward Rapid Assessment69 | Value of QI Educational Intervention24 | Common Elements |

|---|---|---|---|

Planning

|

Gather relevant material

|

Who Benefits: the value of outcomes depends on the stakeholder perspective. Timing of Analysis: prospective vs. retrospective |

Planning

|

| Define the elements of economic appraisal |

Cost Analysis: consider all costs used in service provision. Discerning Benefits: a tangible measure of value is needed. Determine if changes in purchasing could be attributed to the training program. |

Identifying costs | |

Data Collection

|

Identify data Obtain improvement evidence |

Identifying benefits Identifying intangible benefits that will not be included in the ROI estimation |

|

| Isolate Effects of Program | Discerning % attribution to each measure | Discerning attribution | |

Data Analysis

|

Produce ROI impact assessment

|

Calculate the ROI | ROI calculations |

| Reporting |

|

Assess the Sensitivity to changes in assumptions | Sensitivity Analysis |

The Productive Ward Rapid Impact Assessment69 represents a large-scale evaluation of investment in QI capacity building. The ROI was estimated based on case studies in nine selected hospitals in England. Although the initiative is intended to be implemented across hospitals in England's National Health Service (NHS), the Rapid Impact Assessment was limited to this initiative rather than representing a broad system-wide, cross-sectoral evaluation of QI capacity building across the NHS. A second study by McLinden et al24 depicts an ROI assessment of a QI training intervention to improve a back office process in a US hospital setting.

Drawn from shared elements, as depicted in the fourth column in table 3, we identified eight key steps in ROI assessments of QI capacity building:

Planning—stakeholder perspective: The magnitude and value of an economic evaluation will vary depending on the stakeholder perspective selected. In the Productive Ward, for instance, the analysis took a ‘public value perspective’, attempting to include all benefits and costs allocated to every relevant stakeholder.

Planning—temporal perspective: The economic evaluation may be prospective (should the programme be undertaken?), retrospective (what were the results of the programme?) or contemporaneous (should the programme be changed?). In addition, the evaluation should allow enough consideration of midterm and long-term outcomes, especially for long-term interventions.68

Identifying costs: All relevant costs to conduct the intervention or that result from the intervention should be captured, provided they are directly attributable to the intervention. The Productive Ward assessment used national and local data sources and included indepth interviews to retrieve all relevant costs.

Identifying benefits: All relevant benefits should also be identified, including monetary and non-monetary or intangible benefits. For example, the Productive Ward Rapid Assessment included: quality outcomes, productivity and efficiency outcomes, and financial benefits. Financial benefits generated by increased direct patient care time were calculated through excess bed days, length of stay, hospital readmissions, rates of staff absence and stock reduction.

Identifying intangible benefits that will not be included in the ROI estimation: Non-monetary or intangible benefits should always be estimated and reported, even if sometimes they cannot or should not be converted to monetary values and included in the ROI estimation by design.68 In the Productive Ward Rapid Assessment, patient experience, staff satisfaction and harm events, although identified, were not quantified and excluded from the ROI estimation.

Discerning attribution: Identified costs and benefits should only be included in the ROI estimation if attributable to the intervention, and in the proportion attributable to the intervention. This is possibly the most crucial step in the ROI evaluation, due to the challenges in clearly justifying attribution and the associated potential discretional effects on the estimation results. For example, in order to isolate the effect of training, McLinden et al24 asked a group of stakeholders to consider the multiple factors that could be responsible for the financial benefits and then to estimate the percentage attributable to training. Attribution of changes to the Productive Ward was also obtained from the judgement of managers involved in the implementation of the programme during the interviews.

ROI calculations: ROI is calculated as the net benefit (benefits minus costs) divided by costs.68 For the Productivity Ward, the estimated total potential economic impact was calculated by scaling up the evidence from the 9 participating hospital trusts to all 139 wards in England. The estimation was that for every £1 spent, £8.07 would be returned. McLinden et al24 reported that for every $1 invested in training, $1.77 would be returned.

Sensitivity analysis: The results of an economic evaluation are based on assumptions that bring uncertainty to the final ROI estimate. A sensitivity analysis needs to be performed in order to understand the probabilities and magnitude of the variation in evaluation results. The Productive Ward evaluation used a table of risk assessments to discuss the implications of using the wrong assumptions in the model. McLinden et al24 also explored the impact of variations in costs and benefits in the calculations of ROI.

Discussion

Research in QI capacity building assessment is limited in the number and scope of studies, as reflected in the limited findings of our systematic review. While we cast a broad net for our search, it is possible that our search strategy was not sufficiently sensitive or specific to capture all relevant QI capacity building evaluations. However, given the multiple sources searched for this review, including eight indexed databases, plus Google Scholar, Google and targeted searches of governmental and other organisational websites, recommendations from experts and reviews of reference lists of articles identified, we believe it is unlikely that we have missed a system-level evaluation.

Several studies have shown improvement in quality outcomes related to building QI capacity; however, there has not been an emphasis on understanding how much we are getting from these investments. More indepth evaluations are needed to understand when learning occurs, is applied and when it has an impact on patient care. Furthermore, existing studies have substantial variation in evaluation approaches and measures, which reflects the lack of a shared or sufficiently broad vision of how to construct and evaluate QI capacity building. This issue challenges the applicability and generalisability of evidence across care settings and jurisdictions. With a limited base of past work to draw on, we have little evidence to make judgements regarding the appropriate level of QI investments, where these investments should be directed for optimal impact, and the extent and nature of costs related to QI training and projects. Therefore, although most health systems can quantify at least some of their investments in personnel and training dollars, the ROI for QI capacity building at the system level is largely unknown.

Taken together, this review represents a synthesis of the most current knowledge on QI capacity building evaluation at organisation and programme levels that we cautiously used to highlight important elements that are relevant to the system level, and key gaps that need further attention. To guide future evaluation efforts at the health system level, we have consolidated the main elements identified in our review into a Framework to Guide Evaluations of QI Capacity Building, presented in figure 2.

The left side of figure 2 (QI efforts) shows the 5 dimensions and 17 evaluation components identified, and the arrows represent the directional effect between them. Investments in QI capacity building produce QI training and QI activity. QI training and activity generate individual and organisational QI capacity. Organisational and individual QI capacity have an impact on patient and care outcomes. The interdependence between QI training and activity, and between individual and organisational QI capacity, is represented by bidirectional arrows.

The right side of figure 2 (QI evaluations) shows how ‘evaluations of QI capacity building’ (ie, evaluations of QI training or QI programmes/intervention) typically consider characteristics of QI training and/or QI activity and evaluate their effects on organisational and individual QI capacity, and ideally also on patient and care outcomes (arrow A). ‘Evaluations of QI capacity’ may explore the effect of organisational and individual QI capacity in outcomes (arrow B), or be limited to the assessment of the level of QI capacity in an organisation, region or healthcare system (arrow C). Distinctively, ‘evaluations of ROI in QI capacity building’ should start by taking into account the investments in QI capacity building and then evaluate all five dimensions in the framework, including outcomes (arrow D). The framework also incorporates the 8 identified key steps of a QI ROI assessment, advancing Phillip's framework by focusing on QI capacity building through examples provided for each of the 17 evaluation components. These examples show how the components relate to evaluations of ROI in QI capacity building. These evaluation questions are only examples of the many aspects that need to be considered when planning and executing economic assessments of QI capacity building, especially on a large scale.

Although not specifically focused on QI evaluation, a prior systematic review by Kaplan et al70 identified contextual factors that might influence QI success which coincide with our findings, such as leadership from top management, organisational culture, data infrastructure and information systems. Subsequently, Kaplan et al71 used an expert panel to prioritise these findings in a model to understand contextual factors affecting the success of QI projects. Although they identified external factors influencing QI success, these were from the organisational perspective and not at the health system level.

The extensive use of ROI evaluations in many industries contrasts with their slow introduction in health and social care evaluations. Direct transactions between customer and provider normally help quantify value in other industries. However, third-party payment systems in the delivery of healthcare make it difficult to identify opportunities for increasing ROI.24 Another key issue is converting intangible benefits to monetary value to be included in economic evaluations, given the central importance in healthcare of non-monetary outcomes, such as patient experience or health outcomes. This is especially critical in QI at the health system level and for population health, where targeted outcomes can be as ‘non-monetary’ as wait times or quality of life and as ‘intangible’ as innovation, leadership or culture. Phillips68 notes that ‘there is no measure that can be presented to which a monetary value cannot be assigned’, yet the key issues are making credible estimates that are stable over time and at a reasonable cost. Failing to address these issues has the inherent risk of misjudging the real value of QI capacity building investments.

Isolating the effect and discerning attribution of capacity building and training interventions is challenging, even more if doing so at the system level. Typical approaches include the use of control groups and time-series analysis, techniques that are not always plausible when multiple initiatives and programmes are implemented simultaneously. Alternatively, estimation of training impact can be obtained through focus groups or questionnaires, as shown in the examples identified through this review. The important point is to always carefully discern costs and benefits attributable to the intervention. Depending on the robustness of the estimation, error adjustments should be large enough to show reliable evaluation results.68

From the findings of this review, we can conclude that there is an important gap in QI capacity building knowledge and assessment, particularly at the system level. However, the techniques and necessary expertise to start addressing this research gap exist and the necessary resources could be made available. Even based on limited experience in this field, a more extensive use of ROI or other types of economic evaluation of QI capacity building can help close this knowledge gap. After all, ROI assessments are no more than evaluations of the balance between costs and benefits, which is coincidental with widely accepted ‘value’ frameworks in health, such as the Triple Aim. Therefore, a high policy priority going forward is to broaden the vision to pursue more comprehensive system-level evaluation and monitoring of advances in QI capacity building and the impact of investments, in order to truly achieve a better healthcare system for all.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Gustavo Mery @gustavo_mery

Contributors: GM and MJD designed the study. GM and JI collected data and conducted data analysis. GM wrote the manuscript. MJD, GRB and AB made substantial contributions to the identification of relevant literature, the interpretation of findings and were involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically. All authors gave final approval to this manuscript.

Funding: This project was supported by the IDEAS Initiative—Improving and Driving Excellence Across Sectors, a QI capacity building programme in Ontario, Canada, funded by the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Øvretveit J. Does improving quality save money? A review of evidence of which improvements to quality reduce costs to health service providers. London: The Health Foundation, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dentzer S. Still crossing the quality chasm—or suspended over? Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:554–5. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler PS, Riley P, Kwon SW et al. Performance improvement capability: keys to accelerating improvement to hospitals. California Manag Rev 2003;45:12–33. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chassin MR, Loeb JM. The ongoing quality improvement journey: next stop, high reliability. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011;30:559–68. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is “quality improvement”, and how can it transform health care? Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:2–3. 10.1136/qshc.2006.022046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Health Quality Ontario. What is quality improvement? 2014. http://www.hqontario.ca/quality-improvement (accessed 26 Jun 2015).

- 7.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Quality improvement training: scanning the field and developing resources 2011. http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/program_results_reports/2011/rwjf71893 (accessed 29 Feb 2016).

- 8.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Spreading Quality Improvement: Institute for Healthcare Improvement's Open School 2011. http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2011/12/spreading-quality-improvement-.html (accessed 29 Feb 2016).

- 9.Dobrow MJ, Neeson J, Sullivan T. Canadian chief executives’ prescription for higher quality: more clinical engagement, shared accountability and capacity development. Healthc Q 2011;14:18–21. 10.12927/hcq.2011.22645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harvey G, Jas P, Walshe K. Analysing organisational context: case studies on the contribution of absorptive capacity theory to understanding inter-organisational variation in performance improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:48–55. 10.1136/bmjqs-2014-002928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kringos DS, Sunol R, Wagner C et al. The influence of context on the effectiveness of hospital quality improvement strategies: a review of systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:277 10.1186/s12913-015-0906-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bevan H. How can we build skills to transform the healthcare system? J Res Nurs 2010;15:139–48. 10.1177/1744987109357812 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baker GR, MacIntosh-Murray A, Porcellato C et al. High performing healthcare systems: delivering quality by design. Toronto: Longwoods Publishing, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker GR, Denis JL. A comparative study of three transformative healthcare systems: lessons for Canada. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, 2011. http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/commissioned-research-reports/Baker-Denis-EN.pdf?sfvrsn (accessed 29 Feb 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crisp BR, Swerissen H, Duckett SJ. Four approaches to capacity building in health: consequences for measurement and accountability. Health Promot Int 2000;15:99–107. 10.1093/heapro/15.2.99 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Potter C, Brough R. Systemic capacity building: a hierarchy of needs. Health Policy Plan 2004;19:336–45. 10.1093/heapol/czh038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wing KT. Assessing the effectiveness of capacity-building initiatives: seven issues for the field. Nonprof Volunt Sec Q 2004;33:153–60. 10.1177/0899764003261518 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Øvretveit J, Staines A. Sustained improvement? Findings from an independent case study of the Jönköping quality program . Q Manag Health Care 2007;16:68–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: what it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q 1998;76:593–624. 10.1111/1468-0009.00107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement. Exploring accountable care in Canada: integrating financial and quality incentives for physicians and hospitals. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kirkpatrick Partners. The Kirkpatrick Model 2015. http://www.kirkpatrickpartners.com/OurPhilosophy/TheKirkpatrickModel (accessed 28 Jul 2015).

- 22.Tian J, Atkinson NL, Portnoy B et al. A systematic review of evaluation in formal continuing medical education. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2007;27:16–27. 10.1002/chp.89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belfield C, Thomas H, Bullock A et al. Measuring effectiveness for best evidence medical education: a discussion. Med Teach 2001;23:164–70. 10.1080/0142150020031084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McLinden D, Phillips R, Hamlin S et al. Evaluating the future value of educational interventions in a health care setting. Perform Improv Q 2010;22:121–30. 10.1002/piq.20071 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood) 2008;27:759–69. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cornett A, Thomas M, Davis MV et al. Early evaluation results from a statewide quality improvement training program for local public health departments in North Carolina. J Public Health Management Practice 2012;18:43–51. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e31822d2e07 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis MV, Vincus A, Eggers M et al. Effectiveness of public health quality improvement training approaches: application, application, application. J Public Health Manag Pract 2012;18:E1–7. 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182249505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Riley W, Parsons H, McCoy K et al. Introducing quality improvement methods into local public health departments: structured evaluation of a statewide pilot project. Health Serv Res 2009;44(5 Pt 2):1863–79. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01012.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruud KL, Leland JR, Liesinger JT et al. Effectiveness of a quality improvement training course: Mayo clinic quality academy. Am J Med Qual 2012;27:130–8. 10.1177/1062860611415391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ng S, Trimnell J. Evaluation of the IDEAS advanced learning program—year 1. Toronto: Vision & Results, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Daugherty JD, Blake SC, Kohler SS et al. Quality improvement training: experiences of frontline staff. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 2013;27:627–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rask KJ, Gitomer RS, Spell NC et al. A two-pronged quality improvement training program for leaders and frontline staff. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 2011;37:147–53. 10.1016/S1553-7250(11)37018-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blake SC, Kohler SS, Culler SD et al. Designing effective healthcare quality improvement training programs: perceptions of nursing and other senior leaders. J Nurs Educ Pract 2013;3:66–77. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavigne J. Implementing “educating pharmacy students and pharmacists to improve quality” (EPIC) as a requirement at the Wegmans school of pharmacy. Currents Pharm Teach Learn 2012;4:212–16. 10.1016/j.cptl.2012.04.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Warholak TL, Noureldin M, West D et al. Faculty perceptions of the educating pharmacy students to improve quality (EPIQ) program. Am J Pharm Educ 2011;75:163 10.5688/ajpe758163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diaz VA, Carek PJ, Johnson SP. Impact of quality improvement training during residency on current practice. Fam Med 2012;44:569–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canal DF, Torbeck L, Djuricich AM. Practice-based learning and improvement: a curriculum in continuous quality improvement for surgery residents. Arch Surg 2007;142:479–83; discussion 482–3 10.1001/archsurg.142.5.479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Djuricich AM, Ciccarelli M, Swignoski NL. A continuous quality improvement curriculum for residents: addressing core competency, improving systems. Acad Med 2004;79(Suppl 10):S65–7. 10.1097/00001888-200410001-00020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ogrinc G, Headrick LA, Morrison LJ et al. Teaching and assessing resident competence in practice-based learning and improvement. J Gen Intern Med 2004;19:496–500. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30102.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Didic S, Phillips K, Muller-Clemm W et al. Effective governance for quality and patient safety program: an evaluative assessment. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, 2011. http://www.cfhi-fcass.ca/sf-docs/default-source/reports/Effective-Governance-EN.pdf?sfvrsn=0 (accessed 1 Mar 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Evaluating Quality Improvement Training Programs 2013. http://www.rwjf.org/en/library/research/2013/08/evaluating-quality-improvement-training-programs.html (accessed 1 Mar, 2016).

- 42.Morganti KG, Lovejoy S, Haviland AM et al. Measuring success for health care quality improvement interventions. Med Care 2012;50:1086–92. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318268e964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morganti KG, Lovejoy S, Burke B et al. A retrospective evaluation of the perfecting patient care university training program for health care. Am J Med Qual 2014;29:30–8. 10.1177/1062860613483354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stover KE, Tesfaye S, Hailmichael Frew AH et al. Building district-level capacity for continuous improvement in maternal and newborn health. J Midwifery Womens Health 2014;59:S91–100. 10.1111/jmwh.12164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matovu JK, Wanyenze RK, Mawemuko S et al. Strengthening health workforce capacity through work-based training. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2013;13:8 10.1186/1472-698X-13-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Runnacles J, Moult B, Lachman P. Developing future clinical leaders for quality improvement: experience from a London children's hospital. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:956–63. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis MV, Mahanna E, Joly B et al. Creating quality improvement culture in public health agencies. Am J Public Health 2014;104 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Health Quality Ontario. Learning Community Program Implementation Evaluation Final Report. Christine Frank & Associates/Cathexis Conculting Inc 2011. http://www.hqontario.ca/portals/0/Documents/qi/qi-learncomm-implement-evaluation-finalreport-1107-en.pdf (accessed 1 Mar 2016).

- 49.Weiner BJ, Alexander JA, Shortell SM et al. Quality improvement implementation and hospital performance on quality indicators. Health Serv Res 2006;41:307–34. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00483.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gagliardi AR, Majewski C, Victor JC et al. Quality improvement capacity: a survey of hospital quality managers. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:27–30. 10.1136/qshc.2008.029967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ontario Hospital Association. Quality Improvement in Hospitals: OHA survey results 2013. http://www.oha.com/CurrentIssues/Issues/Documents/QI%20Survey_Analysis%20Report%20%28Sept%2010%202013%29.pdf (accessed 1 Mar 2016).

- 52.British Columbia Patient Safety and Quality Council. Education for quality and safety leaders: a needs assessment and program review 2012. https://bcpsqc.ca//documents/2012/11/education.pdf (accessed 1 Mar 2016).

- 53.Lawrence RH, Tomolo AM. Development and preliminary evaluation of a practice-based learning and improvement tool for assessing resident competence and guiding curriculum development. J Grad Med Educ 2011;3:41–8. 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00102.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Batalden PB, Leach D, Swing S et al. General competencies and accreditation in graduate medical education. Health Affairs 2002;21:103–11. 10.1377/hlthaff.21.5.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Butterworth T, Jones K, Jordan S. Building capacity and capability in patient safety, innovation and service improvement: an English case study. J Res Nurs 2011;16:243–51. 10.1177/1744987111406008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Headrick LA, Barton AJ, Ogrinc G et al. Results of an effort to integrate quality and safety into medical and nursing school curricula and foster joint learning. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:2669–80. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.American Academy of Family Physicians. Practice based learning and improvement: recommended curriculum guidelines for family medicine residents 2012. http://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint289C_Learning.pdf (accessed 1 Mar 2016).

- 58.Saskatchewan Health Quality Council. Building a culture of quality improvement in Saskatchewan's health care system: assessing the impact of the health quality council 2010. http://hqc.sk.ca/Portals/0/documents/assess-hqc-impact.pdf (accessed 1 Mar 2016).

- 59.Hutchison B, Levesque JF, Strumpf E et al. Primary health care in Canada: systems in motion. Milbank Q 2011;89:256–88. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00628.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Farley DO, Morton SC, Damberg CL et al. Assessment of the National Patient Safety Initiative: context and baseline evaluation report I. RAND Health 2008. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2005/RAND_TR203.pdf (accessed 1 Mar 2016).

- 61.Headrick LA, Shalaby M, Baum KD et al. Exemplary care and learning sites: linking the continual improvement of learning and the continual improvement of care. Acad Med 2011;86:e6–7. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182308d90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.American Association of Colleges of Nursing. Hallmarks of quality and patient safety: recommended baccalaureate competencies and curricular guidelines to ensure high-quality and safe patient care. J Prof Nurs 2006;22: 329–30. 10.1016/j.profnurs.2006.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cronenwett L, Sherwood G, Barnsteiner J et al. Quality and safety education for nurses. Nurs Outlook 2007;55:122–31. 10.1016/j.outlook.2007.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cronenwett L, Sherwood G, Pohl J et al. Quality and safety education for advanced nursing practice. Nurs Outlook 2009;57:338–48. 10.1016/j.outlook.2009.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Batalden PB, Stevens DP, Kizer KW. Knowledge for improvement: who will lead the learning? Qual Manag Health Care 2002;10:3–9. 10.1097/00019514-200210030-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Splaine ME, Aron DC, Dittus RS et al. A curriculum for training quality scholars to improve the health and health care of veterans and the community at large. Qual Manag Health Care 2002;10:10–18. 10.1097/00019514-200210030-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Splaine ME, Ogrinc G, Gilman SC et al. The department of veterans affairs national quality scholars fellowship program: experience from 10 years of training quality scholars. Acad Med 2009;84:1741–8. 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181bfdcef [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Phillips JJ. Return on investment in training and performance improvement programs. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 69.NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. Rapid Impact Assessment of The Productive Ward. Releasing time to care. Coventry: National Health Institutes 2011. http://www.institute.nhs.uk/quality_and_value/productivity_series/productive_ward.html (accessed 29 Feb 2016).

- 70.Kaplan HC, Brady PW, Dritz MC et al. The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: a systematic review of the literature. Milbank Q 2010;88:500–59. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00611.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kaplan HC, Provost LP, Froehle CM et al. The Model for Understanding Success in Quality (MUSIQ): building a theory of context in healthcare quality improvement. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:13–20. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012431supp_appendix.pdf (206KB, pdf)