Abstract

Introduction

The major paediatric triage systems are primarily based on flow charts involving signs and symptoms for orientation and subjective estimates of the patient's condition. In contrast, the 4-level Paediatric Triage Instrument (PETI) is primarily based on vital parameters and was developed exclusively for paediatric triage in patients with medical symptoms. The aim of this study was to assess the inter-rater reliability of this triage system in children when used by nurses.

Methods

A design was employed in which triage was performed simultaneously and independently by a research nurse and an emergency department (ED) nurse using the PETI. All patients aged ≤12 years who presented at the ED with a medical symptom were considered eligible for participation.

Results

The 89 participants exhibited a median age of 2 years and were triaged by 28 different nurses. The inter-rater reliability between nurses calculated with the quadratic-weighted κ was 0.78 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.89); the linear-weighted κ was 0.67 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.80) and the unweighted κ was 0.59 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.73). For the patients aged <1, 1–3 and >3 years, the quadratic-weighted κ values were 0.67 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.94), 0.86 (95% CI 0.75 to 0.97) and 0.73 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.97), respectively. The median triage duration was 6 min.

Conclusions

The PETI exhibited substantial reliability when used in children aged ≤12 years and almost perfect reliability among children aged 1–3 years. Moreover, rapid application of the PETI was demonstrated. This study has some limitations, including sample size and generalisability, but the PETI exhibited promise regarding reliability, and the next step could be either a larger reliability study or a validation study.

Keywords: PAEDIATRICS, ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE, HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION & MANAGEMENT

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The design of this ‘live’ triage study was drawn up to enable blindness and independency at all phases of the triage procedure.

The design of this study, which resembled a clinical emergency department (ED) setting in that the ED nurses were not recently trained in the use of the PETI and six of them lacked formal training in its use, should strengthen the generalisability to other nurses.

The sample size of this study was relatively small, which resulted in wide CIs and uncertainty in some of the results.

Because of the small sample size and the single-centre design, there are some issues regarding the generalisability of the results.

A small proportion of the participants were triaged to the most urgent level, but this does not necessary result in an overestimation of the reliability because with most triage systems, triage of the most urgent patients is simple.

Introduction

Since the early 1990s, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of emergency department (ED) visits.1 2 In addition to the increase in emergency visits, several other circumstances have contributed to the overcrowding of EDs, including an inadequate inpatient capacity, the increasing complexity of paediatric patients, the lack of medical staff and the lack of easy access to primary care.1 With overcrowding comes greater risks of medical errors and adverse events.1 2 The overcrowding of EDs has made triage systems important, and several such systems, such as the Australasian Triage Scale (ATS), the Manchester Triage System (MTS), the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) and the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) emerged in the 1990s. These four systems are the most established triage systems for adults, and they are also used for paediatric patient populations with some adaptations.3–9 In addition, the Rapid Emergency Triage and Treatment System (RETTS), including a paediatric version (RETTS-p), is widely used in Scandinavian countries.10 11

The triage of children in an ED setting offers several challenges that differ from adult triage. First, infants and smaller children depend almost entirely on their parents and medical professionals for correct judgements of their status. Second, substantial physiological variations and immaturity of organ development make small children more susceptible to sudden deterioration, which necessitates the continuous reassessment of children.12 Some of the currently used paediatric triage systems have reached a substantial level of inter-rater reliability, although there is still room for improvement. In well-conducted studies of simultaneous ‘live’ triage, weighted κ values of 0.57, 0.65, 0.74 and 0.76 have been reported for the ESI V.4, MTS, CTAS and RETTS-p, respectively.5 7 9 10 In addition, two meta-analyses including studies of ‘live’ triage and the triage of paper case scenarios reported correlation coefficients of 0.60 and 0.77 for the CTAS and ESI, respectively, whereas a meta-analysis including only studies applying the triage of paper case scenarios reported a correlation coefficient of 0.40 for the ATS.13–15

One factor that may contribute to errors in triage is that triage decisions are based to a large extent on informed but subjective estimates of the patient's presenting condition, such as estimates of pain and future resource utilisation in the ATS and ESI, respectively.16 17 Another negative factor may be the complexities of triage systems with large numbers of different presenting complaints.8 18 19 To determine acuity levels, these symptoms are accompanied by general and complaint-specific discriminating questions in the MTS and sets of general and complaint-specific criteria in the CTAS. The procedure for determining acuity level in the RETTS is similar to that in the CTAS and MTS in the use of presenting complaints and accompanying discriminating criteria, but in addition, it also relies on vital parameters (VPs).10 11

In contrast to the major triage systems, the Paediatric Triage Instrument (PETI) relies primarily on measurements of VPs that are acquired irrespective of the presenting complaints. The use of VPs is accepted as important in triage because VPs offer objective measurements on which decisions can be based, and such objective measurements are expected to be especially important in children.8 19 Moreover, a triage system based on VPs should be easy and quick to use. An additional possible advantage is increased control of the deterioration of patients because a baseline is established during the first triage, and a rapidly applied triage system makes continuous reassessments more achievable.

The PETI is a four-level triage system that is exclusively applied for paediatric triage and is based primarily on the VPs of patients with medical symptoms. In creating this system, the main focus was placed on achieving an initial assessment that is quick and objective.

The aim of this study was to assess the inter-rater reliability of the PETI in children with medical symptoms when used by nurses. The secondary aims were to assess the inter-rater reliability of the PETI for three different age groups and to assess the duration of the triage procedure associated with the PETI.

Methods

Study design

This study of inter-rater reliability applied a design in which each patient was simultaneously and independently triaged by a research nurse and an ED nurse who were blinded to each other's collection of the data and triage assignments. The participants were included prospectively and consecutively.

Study setting and population

The study was conducted at a county hospital in the centre of Sweden. The department of paediatrics provides care for a population of 60 000 individuals aged 0–18 years with a rich ethnic diversity. The ED at the hospital receives 45 000 patients visits annually, and in 2011, 13% of these visits were made by paediatric patients 12 years or younger with medical symptoms.

All patients aged 12 years or younger who presented to the ED with a medical symptom were considered eligible for inclusion in the study. Only children between the ages of 0 and 12 years were included because a different triage system has been introduced in the ED for children older than 12 years. The number of participants was decided on based on the preplanned data collection time frame, which was limited by resources. Written informed consent was obtained from the parents.

The triage system: PETI

The PETI is a four-level triage system primarily based on measurements of the following five VPs: respiratory rate, heart rate, capillary saturations, capillary refill time and core temperature (see online supplementary appendix 1). The measurement of each of these VPs is compared with an age-specific reference interval. Depending on the degree of deviation, the VP is assigned 1, 2 or 4 points. The final acuity level is given by the sum of the points assigned to each of the five VPs. Summed scores of 0–1, 2–5, 6–9 and ≥10 correspond to acuity levels of ‘non-urgent’ (green), ‘urgent’ (yellow), ‘very urgent’ (orange) and ‘emergent’ (red), respectively. Hence, to limit overtriage, a minimum of 2 points is necessary for triage into the ‘urgent’ acuity level, and a minimum of 6 points is necessary for triage into the ‘very urgent’ acuity level. In addition, to emphasise severe cases, extra weight is added for large deviations in the VPs (4 vs 2 points). The normal reference intervals for the VPs of respiratory rate and heart rate were set according to the Advanced Paediatric Life Support (APLS) system.12 The normal reference value for the capillary refill time was adjusted based on the APLS value with the intention of increasing reliability. The normal reference intervals for saturation and temperature were set according to established experience. The reference intervals for deviations corresponding to 4 points for the VPs of temperature, capillary saturations, heart rate and respiratory rate were set according to the cut-off values for danger zone vitals in the ESI, along with clinical experience.20 The cut-off value for deviations in capillary refill time corresponding to 4 points was set according to the APLS.12 The reference values for deviations corresponding to 1–2 points were evenly distributed between normal and 4 points.

bmjopen-2016-012748supp_appendix.pdf (133.1KB, pdf)

Some signs and symptoms included in the PETI are related to the airway and neurology and were selected from the ABCDE model, including the alert, voice, pain and unresponsive scale (AVPU scale), which individually creates a ‘force majeure’ that complements triage based on VPs (see online supplementary appendix 1).12 Triage based on a ‘force majeure’ is independent from triage based on VPs, and the patient is assigned the highest acuity level between these two methods. These signs and symptoms are assessed prior to or during the collection of VP data. The signs and symptoms of mild recession result in assignment of the patient to the ‘urgent’ acuity level. Any of the following signs and symptoms result in assignment of the patient to the ‘very urgent’ acuity level: compromised airway, severe recession, a sloppy or irritable infant or assessment of the child as voice responsive. Any of the following signs and symptoms result in assignment of the patient to the ‘emergent’ acuity level: airway obstruction, stridor, convulsions or assessment of the child as either pain responsive or unresponsive.

The development of the PETI was influenced by the major triage systems and, more importantly, by paediatric early warning systems, which rely heavily on VPs.21 22 During the development of the PETI, feedback was given by groups of paediatricians and other emergency staff.

Data collection

The ED nurses were trained in the use of the PETI when the system was introduced at the ED 1 year prior to the study. This training was implemented via a 2-hour lecture and through the opportunity to ask questions for 30 min the day the instrument was introduced, or via email, or when the first author was serving at the ED. The research nurse had no previous experience with the PETI and was trained in the use of the system through two 1-hour training sessions prior to the study. The research nurse performed 29 shifts of 6 hours each to recruit and triage patients for the study. All but one shift lasted from 16.00 to 22.00 on normal weekdays. The ED nurses who were working the same 29 shifts during which the research nurse was at the ED participated in the study. According to the established routine in the ED, all triage of children should be performed by an ED nurse.

Triage was performed simultaneously by an ED nurse and the research nurse and included measurements of five VPs and assessments of signs and symptoms related to a ‘force majeure’. Capillary saturation and heart rate was measured using either a Nellcor Puritan Bennett NPB 295 or a Masimo Radical-7 pulse oximeter. Temperature was measured either rectally (in children aged <1 years) using a Terumo C402 digital thermometer or aurally using a Braun ThermoScan 6022 tympanic thermometer. The measurements used to calculate the acuity levels of the PETI were performed via the application of two separate sets of instruments. The nurses concealed their data collection from each other by distancing themselves in the room, with the research nurse angling the instrument in use to shield it from the ED nurse. The ED nurse and the research nurse calculated acuity levels blindly and separately in different rooms, or separated by distance when in the same room. They were informed not to discuss their data collection or the assignment of acuity levels. The research nurse documented when she believed that the blindness and independency of the triage procedure had not been preserved. Only the ED nurse's triage results were used in patient care. The characteristics of the study participants were documented by the research nurse.

Statistical analysis

Inter-rater reliability was calculated for the whole group (primary analysis) and for the following post hoc subgroups: <1, 1–3 and 4–12-year-olds. The choice of subgroups was based on the purposes of analysing a group of patients aged <1 year in whom difficulties in triage have previously been reported and creating groups with a sufficient number of participants for the analyses.7 The primary test of inter-rater reliability that was calculated for the primary and subgroup analyses was Cohen's κ with quadratic weights. The quadratic-weighted κ was chosen because it accounts for the degree of disagreement and the severity of disagreement at higher acuity levels (Microsoft Software. Medcalc Software bvba version 12.4. http://www.medcalc.org/manual/kappa.php (accessed 13 Jan 2013)). Additionally, to enable comparison with other studies, Cohen's κ with linear weights or no weights was also calculated for the whole group. The κ values were interpreted according to the following categories: <0.40 poor–fair, 0.41–0.60 moderate, 0.61–0.80 substantial and 0.81–1.0 almost perfect.23 The duration of triage from the beginning of the collection of the triage data to the assignment of the acuity level was determined for the research nurse. The κ values and 95% CIs were calculated with MedCalc 12.4 (Microsoft Software. Medcalc Software bvba version 12.4).

Results

Data collection was performed from 3 November 2011 to 11 January 2012. Twenty-seven ED nurses participated in the study, six of whom began their employment at the ED after training on the PETI took place and were trained solely by their colleagues while working. The median amount of experience in emergency medicine was 4 years (IQR 2–15) for the ED nurses, and the research nurse had 1.5 years of experience.

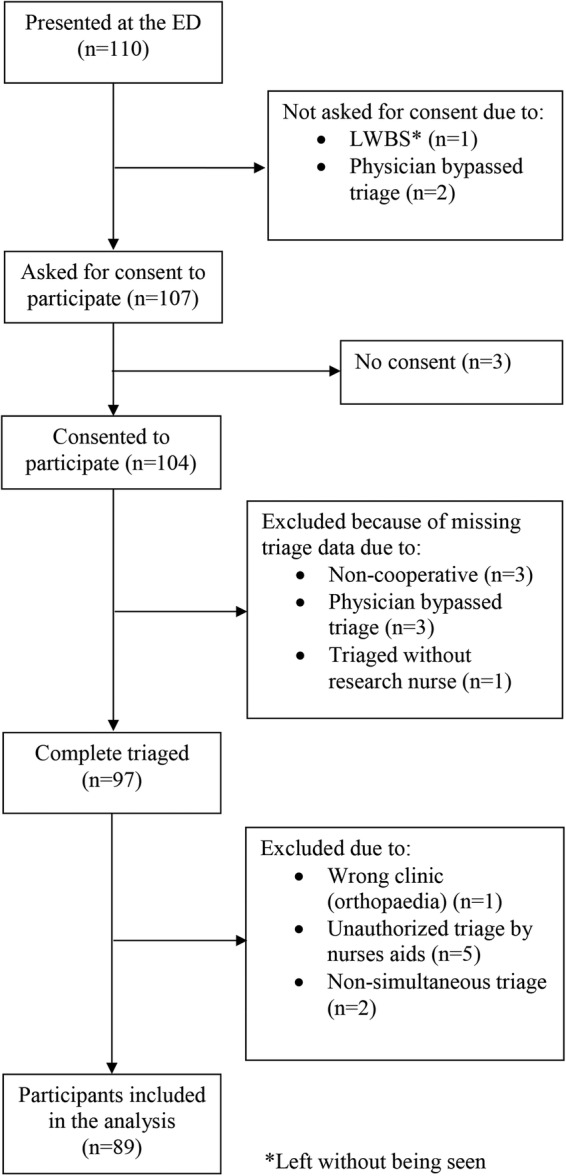

The ED nurses triaged a median of 2 participants each (IQR 1–5). One hundred and four patients agreed to participate in the study, 15 of whom were excluded; thus, 89 participants were included in the analysis (figure 1). The median age of the included patients was 2 years (IQR 0–11) and 48% were girls (table 1). Overall, the characteristics of the study participants corresponded rather well to the characteristics of the patient population (table 1). In 9 of the 89 participants, acuity levels were assigned by ‘force majeure’. The blindness and independency of the triage procedure between the ED and research nurses was preserved for 75 of 89 participants (84%). The reasons for the failure to preserve blindness included the use of the same measurement for temperature due to parental discomfort (n=11) and the need for acute medical procedures in the emergency room (the three emergent participants).

Figure 1.

Flow of participant inclusion.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the participants and the patient population

| Study participants, n=89* | All patients, n=651† | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender female, n (%) | 43 (48) | 286 (44) |

| Gender male, n (%) | 46 (52) | 365 (56) |

| Age | ||

| <1 year, n (%) | 29 (33) | 169 (26) |

| 1–3 years, n (%) | 33 (37) | 306 (47) |

| 4–12 years, n (%) | 27 (30) | 176 (27) |

| Chief symptoms | ||

| Asthma and allergy, n (%) | 10 (11) | 55 (9) |

| Fever, n (%) | 4 (5) | 24 (4) |

| GI and urinary tracts, n (%) | 20 (23) | 96 (15) |

| Neurological, n (%) | 7 (8) | 10 (2) |

| Observation, n (%) | 2 (2) | 32 (5) |

| Respiratory tract, n (%) | 31 (35) | 280 (43) |

| Other, n (%) | 15 (17) | 154 (24) |

*Participants with a medical symptom, non-surgical, non-orthopaedic.

†All patients aged 0–12 years; period 3 November 2010 to 11 January 2011 (ie, the corresponding period a year prior to the study).

The agreement in the acuity level of the PETI between the research nurse and the ED nurses was 73% (table 2). There was no evident systematic disagreement, as either the research nurse or the ED nurse triaged a participant to a higher acuity level than the other nurse on approximately the same number of occasions: 11 (7+3+1) and 13 (7+6) occasions, respectively (table 2). The agreement by age was 76%, 76% and 67% for participants with ages of <1, 1–3 and 4–12 years, respectively (table 3). The median (IQR) duration of the triage procedure was 6 min (4.25–7 min), n=81.

Table 2.

Agreement of acuity levels between the research nurse and the emergency department nurses, n=89

| Research nurse |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED nurse | Non-urgent | Urgent | Very urgent | Emergent | Total |

| Non-urgent (green) | 29* | 7 | 1 | 0 | 37 |

| Urgent (yellow) | 7 | 22* | 3 | 0 | 32 |

| Very urgent (orange) | 0 | 6 | 11* | 0 | 17 |

| Emergent (red) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3* | 3 |

| Total | 36 | 35 | 15 | 3 | 89 |

*Cases showing agreement between the ED nurse and the research nurse.

Table 3.

Agreement by age, n=89 participants

| <1 year | 1–3 years | 4–12 years | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreement | 22 | 25 | 18 | 65 |

| Disagreement by one level | 6 | 8 | 9 | 23 |

| Disagreement by two levels | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 29 | 33 | 27 | 89 |

The inter-rater reliability values for the nurses were 0.78 (95% CI 0.67 to 0.89) based on the quadratic-weighted κ, 0.67 (95% CI 0.56 to 0.80) based on the linear-weighted κ and 0.59 (95% CI 0.44 to 0.73) based on the unweighted κ. (The corresponding κ values, including cases with unauthorised triage decisions by nurse aids, were 0.78, 0.68 and 0.58, n=94).

The quadratic-weighted κ (95% CI) values were 0.67 (0.39 to 0.94), 0.86 (0.75 to 0.97) and 0.73 (0.49 to 0.97) for patients with ages of <1, 1–3 and 4–12 years, respectively.

Discussion

This study demonstrated substantial inter-rater reliability of the new PETI triage system for paediatric patients aged ≤12 years. Additionally, the time required for the completion of the PETI was quite short. The PETI therefore exhibited promise, particularly considering that this study was conducted in a clinical setting in which the ED nurses received no extra training or practice in the triage of case scenarios prior to the study of ‘live’ triage, which is common in other studies.3 7 9 In addition, an effort was made to perform the triage procedure as independently and blinded as possible, and as reported, this was achieved in 84% of the participants.

The level of reliability observed in our study for the PETI triage instrument is comparable to the best κ values for simultaneous ‘live’ triage that have previously been published. Quadratic-weighted κ values of 0.65, 0.74 and 0.76 have been reported for the MTS, CTAS and RETTS-p, respectively, whereas a linear-weighted κ for the ESI V.4 was reported as 0.57.5 7 9 10 While it is difficult to conduct a study of ‘live’ triage with blindness and independency at all phases of triage, they are important factors.24 The studies of the RETTS, CTAS, MTS and ESI V.4 were large, well-conducted studies and the latter three were multicentre studies with superior generalisability to this study of the PETI. However, by study design, the nurses that performed triage in the studies of the RETTS and CTAS shared VP data to some degree for all of the participants.5 10 Similarly, in the studies of the MTS and ESI V.4, the independency regarding the VP data and other information on which to base the acuity level assignment was not stated.7 9 Triage is not only about assigning an acuity level but also about obtaining information on which to base the assignment. Some studies of ‘live’ triage have obtained higher κ values in the range of 0.8–0.9 for the ESI V.3 and 4.3 6 These studies exhibited drawbacks, including limited sample size and total dependency of the VP data used for the assignment of acuity level, which makes the interpretation of their findings questionable.24 In addition, some studies that employed the triage of paper case scenarios have also reported high κ values in the range of 0.8–0.9 for the ESI V.4, MTS and RETTS-p.4 7 8 10 11 25 Similarly, one meta-analysis, which to a large extent, is based on studies of paper case scenarios reported a correlation coefficient of 0.77 for the ESI.15 One could argue that case scenarios do not reflect the real clinical setting in which the interactions between the nurse, patient, environment and triage system may contribute to mistriage.18 24 Indeed, in studies in which paediatric paper case scenarios and ‘live’ paediatric patients were triaged within the same study, the κ values were ∼0.06–0.2 units higher for case scenarios than for ‘live’ triage.3 7 9 10 In contrast, a study that compared ‘live’ triage with case scenarios based on the use of the CTAS in a mixed population of adults and children found that the κ value was higher for the ‘live’ use of the triage algorithm.26 However, the use of a mixed population in this study makes the comparison of results between studies difficult.

The PETI exhibited a tendency towards showing the best reliability in children aged 1–3 years. A possible explanation for this finding is that the VPs provided a clearly defined framework for the triage of children who lack the ability to efficiently communicate. It has previously been demonstrated that complementing subjective triage decisions with VP data often results in changes in triage decisions in children aged ≤2 years and in children whose parents have communication difficulties.27 The PETI exhibited a tendency towards inferior reliability for children aged <1 year, which agrees with previous results for the ESI.7 In general, triage in infants is particularly difficult because the severity of illness is expressed in multiple and subtle manners and can change rapidly.12 However, this observation should be regarded with caution because it stemmed from a discrepancy of two levels in a singly participant.

As assessment using the PETI was shown to be rapid, this tool will facilitate retriage and thereby facilitate the control of patient deterioration. It will also potentially decrease the strain on staff and contribute to resource effectiveness.

It has previously been shown that paediatric triage systems that rely to a large extent on VPs are prone to overtriage (low specificity).28 However, in developing the PETI, the risk of overtriage was compensated through the levels in the scoring system, such that a minimum of 2 points was required for triage into the ‘urgent’ acuity level, and a minimum of 6 points was required for triage into the ‘very urgent’ acuity level. As this was not a validation study, there were no available data on the participants' ‘true’ acuity levels, and it is not possible to answer the question of whether triage with the PETI is prone to overtriage or undertriage. Nevertheless, it is notable that ∼40% of the participants were triaged to each of the two lowest acuity levels (research nurse: 36/89 ‘non-urgent’ and 35/89 ‘urgent’) (table 2).

Improvements in the measures employed in the PETI should likely focus on the VPs of respiratory rate and capillary refill because these VPs rely heavily on estimates and skill. Furthermore, the accuracy of different types and brands of measurement devices have to be taken into account with respect to limits for normal reference values, as consistent measurement deviations from the standard may have an influence on the validity of the PETI. Regarding triage based on ‘force majeure’, the relative position between stridor and severe recession should be considered in the process of improvements. Additionally, in the table illustrating the reference values for the VPs (see online supplementary appendix 1), detected errors should be revised, including gaps in the reference intervals for heart rate, respiratory rate and temperature. Minor revisions of the lay-out have already been incorporated.

This study has some limitations and some strengths. First, comparisons with studies on commonly used paediatric triage systems are difficult because the PETI is a four-level system, whereas the others are five-level systems. However, it has been suggested that κ values in general, and quadratically weighted κ values in particular, increase as the number of categories in a system increase.29 30 Second, a small proportion of the participants were triaged to the most urgent level (n=3), which seems to be a common problem in studies of ‘live’ triage but does not necessary result in the overestimation of κ values because with most triage systems, triage of the most urgent patients is simple.5 7 9 30 Third, the sample size of this study was relatively small, which resulted in wide CIs and uncertainty in some of the results. For instance, the linear-weighted κ for the whole group exhibited a 95% CI that stretched below the lower limit of the substantial category. Fourth, even though the characteristics of the participants in this study resembled those of the patient population, there are some issues regarding the generalisability of the results. The small sample size makes it likely that not all possible presenting complaints of the population were covered in the triage of the participants. In addition, the single-centre design is a cause of concern, as the population, standard practices and workload can differ at other centres. Furthermore, one could argue that the study design, involving only one research nurse, could affect generalisability to other nurses. However, this should be determined by the total number of nurses performing triage, and the 27+1 nurses included in this study should be sufficient. The use of a single research nurse is less likely to be a problem related to generalisability than to an increased risk of underestimating reliability. This situation arises because if the triage level of the sole research nurse is generally higher or lower than those of the ED nurses, it should be manifested as systematic disagreement, with a concomitant underestimation of the reliability as a result.31 32 However, no systematic disagreement was evident in the present study (table 2). In addition, generalisability to other nurses should be strengthened by the design of this study, which resembled a clinical ED setting, in that the ED nurses were not recently trained in the use of the PETI, and six of them lacked formal training in its use, only having been trained by their colleagues while working. Fifth, another strength of this study compared with other studies of ‘live’ triage was the study design, which was structured to enable blindness and independency at all phases of the triage procedure. Total independency was not achieved for all of the participants but compared with other studies, the level of independency seemed high.3 5–7 9 10

In conclusion, our results suggest that the PETI has substantial reliability when used in paediatric patients aged 0–12 years and almost perfect reliability for patients aged 1–3 years. Moreover, this instrument can be rapidly administered. These findings indicate that triage relying on VPs is advantageous mostly among younger children, in whom the ability to perform triage relying on communication is limited. This study has some limitations including sample size and generalisability, but the PETI exhibited promise regarding reliability, and the next step could be either a larger reliability study or a validation study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Antonis Valachis for critically reviewing the manuscript, Lovisa Graflund for data collection, Anna Ekholm for statistical analysis and the ED nurses for cooperation in the triage procedure.

Footnotes

Contributors: JK is responsible for development of the PETI. JK and SE are responsible for design of the study, data interpretation and participation in the statistical analysis. JK is responsible for drafting the manuscript and participation in the acquisition of the data. SE is responsible for critical revision and finalisation of the manuscript.

Funding: Centre for Clinical Research Sörmland, Uppsala University, Eskilstuna, Sweden.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The regional board of ethics in Stockholm, reference 2011/11-31/12.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Hostetler MA, Mace S, Brown K et al. Emergency department overcrowding and children. Pediatr Emerg Care 2007;23:507–15. 10.1097/01.pec.0000280518.36408.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tang N, Stein J, Hsia RY et al. Trends and characteristics of US emergency department visits, 1997–2007. JAMA 2010;304:664–70. 10.1001/jama.2010.1112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumann MR, Strout TD. Evaluation of the Emergency Severity Index (version 3) triage algorithm in pediatric patients. Acad Emerg Med 2005;12:219–24. 10.1197/j.aem.2004.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Durani Y, Brecher D, Walmsley D et al. The Emergency Severity Index Version 4: reliability in pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Care 2009;25:751–3. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3181b0a0c6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gravel J, Gouin S, Goldman RD et al. The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale for children: a prospective multicenter evaluation. Ann Emerg Med 2012;60:71–7. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green NA, Durani Y, Brecher D et al. Emergency Severity Index version 4: a valid and reliable tool in pediatric emergency department triage. Pediatr Emerg Care 2012;28:753–7. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182621813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Travers DA, Waller AE, Katznelson J et al. Reliability and validity of the emergency severity index for pediatric triage. Acad Emerg Med 2009;16:843–9. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00494.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Veen M, Moll HA. Reliability and validity of triage systems in paediatric emergency care. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2009;17:38 10.1186/1757-7241-17-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Veen M, Teunen-van der Walle VF, Steyerberg EW et al. Repeatability of the Manchester Triage System for children. Emerg Med J 2010;27:512–6. 10.1136/emj.2009.077750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henning B, Lydersen S, Døllner H. A reliability study of the rapid emergency triage and treatment system for children. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2016;24:19 10.1186/s13049-016-0207-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westergren H, Ferm M, Häggström P. First evaluation of the paediatric version of the Swedish rapid emergency triage and treatment system shows good reliability. Acta Paediatr 2014;103:305–8. 10.1111/apa.12491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Advanced Life Support Group. Advanced paediatric life support: the practical approach. 4th edn Malden, MA: BMJ Books, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ebrahimi M, Heydari A, Mazlom R et al. The reliability of the Australasian Triage Scale: a meta-analysis. World J Emerg Med 2015;6:94–9. 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2015.02.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mirhaghi A, Heydari A, Mazlom R et al. The reliability of the Canadian triage and acuity scale: meta-analysis. N Am J Med Sci 2015;7:299–305. 10.4103/1947-2714.161243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirhaghi A, Heydari A, Mazlom R et al. Reliability of the emergency severity index: meta-analysis. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J 2015;15:e71–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Gerven R, Delooz H, Sermeus W. Systematic triage in the emergency department using the Australian National Triage Scale: a pilot project. Eur J Emerg Med 2001;8:3–7. 10.1097/00063110-200103000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wuerz RC, Milne LW, Eitel DR et al. Reliability and validity of a new five-level triage instrument. Acad Emerg Med 2000;7:236–42. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01066.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moll HA. Challenges in the validation of triage systems at emergency departments. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:384–8. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warren DW, Jarvis A, LeBlanc L et al. Revisions to the Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale paediatric guidelines (PaedCTAS). CJEM 2008;10:224–43. 10.1017/S1481803500010149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilboy N, Tanabe P, Travers D et al. Emergency severity index, version 4: implementation handbook. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan H, Hutchison J, Parshuram CS. The Pediatric Early Warning System score: a severity of illness score to predict urgent medical need in hospitalized children. J Crit Care 2006;21:271–8. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2006.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haines C, Perrott M, Weir P. Promoting care for acutely ill children-development and evaluation of a paediatric early warning tool. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2006;22:73–81. 10.1016/j.iccn.2005.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kottner J, Audige L, Brorson S et al. Guidelines for Reporting Reliability and Agreement Studies (GRRAS) were proposed. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:96–106. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jafari-Rouhi AH, Sardashti S, Taghizadieh A et al. The Emergency Severity Index, version 4, for pediatric triage: a reliability study in Tabriz Children's Hospital, Tabriz, Iran. Int J Emerg Med 2013;6:36 10.1186/1865-1380-6-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Worster A, Sardo A, Eva K et al. Triage tool inter-rater reliability: a comparison of live versus paper case scenarios. J Emerg Nurs 2007;33:319–23. 10.1016/j.jen.2006.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cooper RJ, Schriger DL, Flaherty HL et al. Effect of vital signs on triage decisions. Ann Emerg Med 2002;39:223–32. 10.1067/mem.2002.121524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roland D, McCaffery K, Davies F. Scoring systems in paediatric emergency care: panacea or paper exercise? J Paediatr Child Health 2016;52:181–6. 10.1111/jpc.13123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Wulp I, van Stel HF. Adjusting weighted kappa for severity of mistriage decreases reported reliability of emergency department triage systems: a comparative study. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1196–201. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Wulp I, van Stel HF. Calculating kappas from adjusted data improved the comparability of the reliability of triage systems: a comparative study. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:1256–63. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Svensson E. Different ranking approaches defining association and agreement measures of paired ordinal data. Stat Med 2012;31:3104–17. 10.1002/sim.5382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res 2005;19:231–40. 10.1519/15184.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012748supp_appendix.pdf (133.1KB, pdf)