Abstract

Objectives

To clarify the social disadvantages associated with myasthenia gravis (MG) and examine associations with its disease and treatment.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting and participants

We evaluated 917 consecutive cases of established MG seen at 13 neurological centres in Japan over a short duration.

Outcome measures

All patients completed a questionnaire on social disadvantages resulting from MG and its treatment and a 15-item MG-specific quality of life scale at study entry. Clinical severity at the worst condition was graded according to the MG Foundation of America classification, and that at the current condition was determined according to the quantitative MG score and MG composite. Maximum dose and duration of dose ≥20 mg/day of oral prednisolone during the disease course were obtained from the patients' medical records. Achievement of the treatment target (minimal manifestation status with prednisolone at ≤5 mg/day) was determined at 1, 2 and 4 years after starting treatment and at study entry.

Results

We found that 27.2% of the patients had experienced unemployment, 4.1% had been unwillingly transferred and 35.9% had experienced a decrease in income, 47.1% of whom reported that the decrease was ≥50% of their previous total income. In addition, 49.0% of the patients reported feeling reduced social positivity. Factors promoting social disadvantages were severity of illness, dose and duration of prednisolone, long-term treatment, and a depressive state and change in appearance after treatment with oral steroids. Early achievement of the treatment target was a major inhibiting factor.

Conclusions

Patients with MG often experience unemployment, unwilling job transfers and a decrease in income. In addition, many patients report feeling reduced social positivity. To inhibit the social disadvantages associated with MG and its treatment, greater focus needs to be placed on helping patients with MG resume a normal lifestyle as soon as possible by achieving the treatment target.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, SOCIAL MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To avoid inclusion biases, we examined consecutive cases.

We systematically analysed associations of social disadvantages among a large number of patients with myasthenia gravis using detailed clinical parameters.

This study was limited by its cross-sectional and partly retrospective design and the fact that it was dependent on patients' self-reported data.

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is a neuromuscular disease that used to be considered severe and was associated with a high mortality rate; however, owing to current treatments, MG has largely become non-lethal.1 2 Still, even today, many patients with MG find it difficult to maintain their daily activity levels due to insufficient improvement in disease status, and the long-term side effects of treatment with oral corticosteroids,2–5 because full remission without steroid treatment is rare in MG.3 4 6 Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is reduced in many patients with MG.3 4 7–13 Analyses of detailed clinical data have consistently revealed that both disease severity and oral corticosteroid dose have significant negative effects on self-perceived HRQOL among patients with MG.3 4 The oral corticosteroid dose has been shown to affect items of the MG-QOL15, a 15-item MG-specific quality of life scale,14 15 associated with social or community mobility.4 It is possible that side effects resulting from treatment with corticosteroids, such as problems associated with appearance or a depressive state, negatively affect personal relationships, positive thinking and social activities.4 16

Many patients with MG cannot fully participate in social activities due to the effects of the disease and its treatment.4 9–13 These patients therefore appear to suffer social disadvantages such as unemployment and a decrease in income, which can lead to a lower HRQOL.9–11 13 However, information regarding the prevalence of these disadvantages and their detailed associations with MG remains scarce. Therefore, we conducted a cross-sectional questionnaire survey to obtain information on social disadvantages experienced by patients with MG. We also examined possible associations with detailed clinical parameters.

Patients and methods

Patients

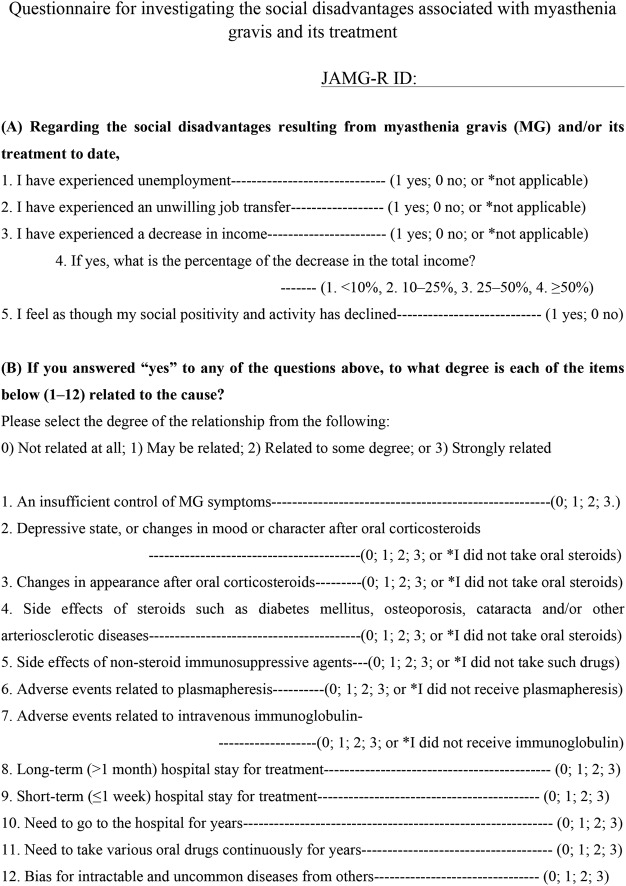

This study was conducted at 13 neurological centres (Japan MG Registry Group, see online supplementary table S1) in Japan. We evaluated patients with established MG between April and July 2015. To avoid potential bias, we enrolled consecutive patients with various disease statuses over a short duration (4 months). During this period, a total of 1088 patients with MG visited our hospitals. From this group we were able to collect full detailed clinical data from 923 patients, and 165 were excluded from the study because of insufficient data collection. Data collected included present disease status, past course of MG Foundation of America (MGFA) postintervention status, and current and past treatment regimens. Among these 923 patients, 917 responded completely to a questionnaire we conducted on social disadvantages resulting from MG and its treatment (figure 1), provided written informed consent and underwent analysis.

Figure 1.

Questionnaire on social disadvantages resulting from MG and its treatment. MG, myasthenia gravis.

bmjopen-2016-013278supp_table1.pdf (48.9KB, pdf)

The diagnosis of MG was based on clinical findings (fluctuating symptoms with easy fatigability and recovery after rest) with amelioration of symptoms after intravenous administration of anticholinesterase, decremental muscle response to a train of low-frequency repetitive nerve stimuli of 3 Hz, or the presence of autoantibodies specific for the acetylcholine receptor (AChR) of skeletal muscle (AChR-Ab) or for muscle-specific tyrosine kinase (MuSK-Ab).

Questionnaire on social disadvantages resulting from MG and its treatment

In the present questionnaire survey (figure 1), we first elucidated whether each patient had experienced unemployment, an unwilling job transfer and/or a decrease in income (figure 1A, items 1–3). For the patients who had experienced a decrease in income, we further asked to what degree their previous total income had decreased (figure 1A, item 4). We also asked whether the patients felt that their social positivity and activity had declined due to MG and/or its treatment (figure 1A, item 5). Only social disadvantages after disease onset were taken into account.

For the patients who answered ‘yes’ to any of the question items 1–3 or 5 (figure 1A), we then asked to what degree (0–3) they thought that each of the 12 items were possible causes of their experienced social disadvantages (figure 1B, items 1–12). Correlations between the degree (0–3) of each of the 12 items and each social disadvantage were then calculated (table 1). This questionnaire was newly developed for this survey.

Table 1.

Associations between question items and social disadvantages (Spearman rank correlation)

| Correlation (95% CI) with social disadvantages, p Value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Question item | Unemployment or unwilling transfer (213/486 cases) | Decrease in income (244/486 cases) | Reduced social positivity (449/486 cases) |

| 1. Insufficient control of symptoms | 0.19 (0.095 to 0.285), <0.0001 | 0.08 (−0.01 to 0.18), 0.05 | 0.05 (−0.04 to 0.14), 0.13 |

| 2. Depressive state, changes in mood or character after PSL (PSL use, 81% of subjects) | 0.10 (0.00 to 0.19), 0.03 | 0.02 (−0.08 to 0.12), 0.36 | 0.20 (0.10 to 0.28), <0.0001 |

| 3. Changes in appearance after PSL (PSL use, 81% of 486 participants) | 0.07 (−0.03 to 0.16), 0.10 | 0.05 (−0.05 to 0.15), 0.14 | 0.20 (0.11 to 0.28), <0.0001 |

| 4. Diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, cataracta and/or other arteriosclerotic diseases (PSL use, 81% of participants) | 0.05 (−0.05 to 0.15), 0.16 | 0.13 (0.03 to 0.22), 0.006 | 0.12 (0.03 to 0.21), 0.005 |

| 5. Side effects related to non-steroid immunosuppressive agents (CNI use, 53%; AZA use, 5%) | −0.02 (−0.12 to 0.07), 0.31 | 0.05 (−0.05 to 0.15), 0.16 | 0.08 (−0.01 to 0.17), 0.04 |

| 6. Adverse events related to plasmapheresis (28%) | 0.04 (−0.06 to 0.14), 0.21 | 0.07 (−0.03 to 0.17), 0.08 | 0.04 (−0.05 to 0.13), 0.20 |

| 7. Adverse events related to intravenous immunoglobulin (16%) | 0.05 (−0.05 to 0.15), 0.17 | 0.07 (−0.03 to 0.17), 0.08 | 0.06 (−0.03 to 0.15), 0.08 |

| 8. Long-term (>1 month) hospital stay | 0.20 (0.10 to 0.29), <0.0001 | 0.27 (0.19 to 0.37), <0.0001 | −0.05 (−0.14 to 0.04), 0.12 |

| 9. Short-term (≤1 week) hospital stay | 0.12 (0.02 to 0.24), 0.006 | 0.13 (0.04 to 0.23), 0.003 | 0.09 (0.00 to 0.17), 0.03 |

| 10. Need to go to the hospital for years | 0.16 (0.07 to 0.26), <0.001 | 0.15 (0.06 to 0.25), <0.001 | 0.03 (−0.06 to 0.12), 0.25 |

| 11. Need to take various oral drugs for years | 0.05 (−0.05 to 0.15), 0.16 | 0.07 (−0.03 to 0.16), 0.10 | 0.13 (0.04 to 0.21), 0.002 |

| 12. Bias for intractable and uncommon diseases from others | 0.16 (0.06 to 0.26), <0.001 | 0.02 (−0.08 to 0.12), 0.35 | 0.21 (0.12 to 0.30), <0.0001 |

Significant correlations are indicated by bold font.

AZA, azathioprine; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; PSL, prednisolone.

Clinical factors from examinations and records

As shown in table 2, clinical factors were evaluated for each patient and entered into correlation analysis with the social disadvantages. Clinical severity at the worst condition was classified according to MGFA classifications17 and, in some patients (792/917), was determined according to the quantitative MG score (QMG),17 from medical records and partly by analyses of information retrospectively. Clinical severity at the current condition was determined according to QMG and the MG composite (MGC),18 19 for all patients, who completed the Japanese version of the MG-QOL15 (MG-QOL15-J),3 at study entry. Clinical status following treatment was categorised according to MGFA postintervention status.17 Previously, minimal manifestations (MM) or better status with prednisolone (PSL) at ≤5 mg/day (MM or better-5 mg) was identified as a practical treatment target,3 4 as the HRQOL of patients with this status was reported to be as good as that of complete stable remission (CSR).3 4 This category grouping into MM or better status (ie, MM, pharmacological remission or CSR) and a cut-off of the PSL dose at 5 mg/day were proposed according to the results of a previous decision tree analysis for good HRQOL.3 The achievement of MM or better-5 mg lasting more than 6 months was determined at 1, 2 and 4 years into treatment from medical records and partly by analyses of information retrospectively, as well as at study entry. The maximum and current dose of oral PSL and the duration of oral PSL≥20 mg/day were obtained from the patients' medical records. Serum AChR-Ab titres were estimated by radioimmunoassay using 125I-α-bungarotoxin, and levels ≥0.5 nM were regarded as positive. MuSK-Ab was measured using a commercially available radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RSR, Cardiff, UK).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and associations between clinical factors and social disadvantages (Spearman rank correlation)

| Correlation (95% CI) with social disadvantages, p value |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical factor | Mean±SD (range) (n=917) |

Unemployment or unwilling transfer (213/680 cases) | Decrease in income (244/680 cases) | Reduced social positivity (449/917 cases) |

| Age, years | 57.1±15.4 (19–93) | −0.08 (−0.16 to −0.01), 0.02 | −0.07 (−0.14 to 0.01), 0.04 | 0.00 (−0.07 to 0.07), 0.49 |

| Female (%) | 65.2 (598/917) | 0.11 (0.00 to 0.18), 0.02 | 0.01 (−0.06 to 0.09), 0.39 | 0.17 (0.10 to 0.24), <0.0001 |

| Time since onset, years | 11.9±10.7 (0.1–83) | 0.08 (0.00 to 0.15), 0.02 | −0.01 (−0.08 to 0.07), 0.43 | 0.00 (−0.07 to 0.08), 0.45 |

| Age at onset, years | 45.4±18.1 (3–91) | −0.11 (−0.18 to−0.04), 0.0025 | −0.04 (−0.12 to 0.03), 0.12 | −0.03 (−0.10 to 0.04), 0.22 |

| Thymectomy, per cent | 52.4 (482/917) | 0.18 (0.10 to 0.25), <0.0001 | 0.21 (0.13 to 0.28), <0.0001 | 0.12 (0.05 to 0.19), 0.0003 |

| Thymoma, per cent | 25.0 (230/917) | 0.01 (−0.09 to 0.10), 0.46 | 0.05 (−0.05 to 0.15), 0.15 | 0.01 (−0.08 to 0.11), 0.38 |

| AChR-Ab positivity, per cent | 81.1 (744/917) | −0.08 (−0.16 to −0.01), 0.02 | −0.08 (−0.16 to −0.01), 0.01 | −0.05 (−0.12 to 0.02), 0.07 |

| MuSK-Ab positivity, per cent | 2.5 (23/917) | 0.12 (0.00 to 0.23), 0.03 | 0.07 (−0.05 to 0.18), 0.14 | 0.09 (−0.03 to 0.20), 0.07 |

| MGFA classification (worst) | I/II/III/IV/V 208/392/186/37/94 |

0.28 (0.21 to 0.35), <0.0001 | 0.31 (0.24 to 0.38), <0.0001 | 0.22 (0.15 to 0.28), <0.0001 |

| Bulbar symptoms, per cent (worst) | 49.4 (453/917) | 0.17 (0.10 to 0.25), <0.0001 | 0.18 (0.10 to 0.25), <0.0001 | 0.13 (0.06 to 0.20), 0.0002 |

| Worst QMG (n=792) | 13.5±7.5 (1–39) | 0.26 (0.18 to 0.33), <0.0001 | 0.32 (0.24 to 0.39), <0.0001 | 0.25 (0.17 to 0.32), <0.0001 |

| Current QMG | 6.6±4.9 (0–29) | 0.20 (0.13 to 0.27), <0.0001 | 0.20 (0.12 to 0.27), <0.0001 | 0.27 (0.20 to 0.34), <0.0001 |

| Current MGC | 4.3±5.2 (0–32) | 0.21 (0.14 to 0.28), <0.0001 | 0.21 (0.13 to 0.28), <0.0001 | 0.28 (0.22 to 0.35), <0.0001 |

| Current MG-QOL15-J | 13.8±13.2 (0–60) | 0.35 (0.28 to 0.41), <0.0001 | 0.34 (0.27 to 0.40), <0.0001 | 0.48 (0.43 to 0.54), <0.0001 |

| Peak dose of PSL, mg/day | 22.0±19.6 (0–80) | 0.16 (0.88 to 0.24), <0.0001 | 0.22 (0.15 to 0.30), <0.0001 | 0.08 (0.01 to 0.15), 0.0143 |

| Duration of PSL≥20 mg/day, years | 0.72±1.7 (0–19.6) | 0.19 (0.11 to 0.27), <0.0001 | 0.22 (0.14 to 0.30), <0.0001 | 0.15 (0.07 to 0.22), <0.0001 |

| Current dose of PSL, mg/day | 4.4±5.0 (0–40.0) | 0.11 (0.03 to 0.19), 0.003 | 0.12 (0.05 to 0.20), 0.0011 | 0.11 (0.04 to 0.18), 0.002 |

| MM or better with 5 mg at 1 year into treatment, per cent | 34.0 (299/880) | −0.17 (−0.24 to −0.09), <0.0001 | −0.17 (−0.25 to −0.09), <0.0001 | −0.19 (−0.26 to −0.11), <0.0001 |

| MM or better with 5 mg at 2 years into treatment, per cent | 40.5 (298/735) | −0.15 (−0.24 to −0.07), 0.0002 | −0.12 (−0.21 to−0.04), 0.003 | −0.17 (−0.25 to −0.09), <0.0001 |

| MM or better with 5 mg at 4 years into treatment, per cent | 46.1 (236/512) | −0.20 (−0.29 to −0.11), <0.0001 | −0.17 (−0.26 to −0.08), <0.0001 | −0.23 (−0.31 to −0.15), <0.0001 |

| MM or better with 5 mg at present, per cent | 48.9 (448/917) | −0.17 (−0.24 to −0.10), <0.0001 | −0.15 (−0.23 to −0.08), <0.0001 | −0.22 (−0.30 to −0.16), <0.0001 |

Significant correlations are indicated by bold font.

AChR-Ab, antiacetylcholine receptor antibody; MG, myasthenia gravis; MGC, myasthenia gravis composite; MGFA, Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America; MG-QOL15, 15-item MG-specific quality of life scale; MG-QOL15-J, Japanese version of the MG-QOL15; MM, minimal manifestations; MuSK-Ab, muscle-specific kinase antibody; PSL, prednisolone; QMG, MGFA quantitative MG score.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the study.

Statistical analysis

Associations between various clinical parameters and experiences of social disadvantages were evaluated using Spearman rank correlations. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed in an attempt to determine the parameters most significantly associated with social disadvantages. All continuous data are expressed as the mean±SD and range (minimum–maximum). Statistical analyses were performed using UNISTAT V.5.6 (Unistat, London, UK).

Results

Frequency of social disadvantages resulting from MG and its treatment

Among the 917 patients with MG who answered our questionnaire survey, 237 responded with ‘not applicable (did not receive income from employment)’ to the question items shown in figure 1A, items1–3. After excluding these patients, 185 (27.2%) out of the remaining 680 answered ‘I have experienced unemployment’ (unemployment rate in the general population of Japan is 3–4%, http://www.stat.go.jp/english/index.htm), 28 (4.1%) answered ‘I have experienced an unwilling job transfer’ and 244 (35.9%) answered ‘I have experienced a decrease in income’. Out of 244 who reported experiencing a decrease in income, 115 (47.1%) answered that the decrement in total income was ≥50%.

Among the 917 total patients, 449 (49.0%) answered ‘My social positivity and activity were reduced’, and 486 answered ‘yes’ to at least one of the question items in figure 1A, items 1–3 and 5. The experiences of unemployment or unwilling job transfer and that of a decrease in income showed significant correlations to the perception of reduced social positivity and activity (r=0.35, p<0.0001; r=0.35, p<0.0001; Spearman rank correlation).

Possible causes perceived by patients and correlations with social disadvantages

Correlations between social disadvantages and the degree (0–3) to which the 486 applicable patients felt that each of the 12 question items in figure 1B were possible causes of these disadvantages are shown in table 1.

The items that exhibited significant positive correlations (p<0.001, r≥0.15) to the ‘experience of unemployment or unwilling job transfer’ were: ‘an insufficient control of MG symptoms’; ‘long-term (>1 month) hospital stay for treatment’; ‘need to go to the hospital for years’ and ‘bias for intractable and uncommon diseases from others’. Significant positive correlations with ‘experience of a decrease in income’ were ‘long-term (>1 month) hospital stay for treatment’ and ‘need to go to hospital for years’, and those with ‘reduced social positivity and activity’ were ‘depressive state, changes in mood or character after oral corticosteroids’, ‘changes in appearance after oral corticosteroids’ and ‘bias for intractable and uncommon diseases from others’.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis using the 12 items as variables revealed ‘an insufficient control of MG symptoms’ (OR=1.35, p=0.003); ‘long-term (>1 month) hospital stay for treatment’ (1.26, 0.009); ‘need to go to the hospital for years’ (1.34, 0.023) and ‘bias for intractable and uncommon diseases from others’ (1.32, 0.014) as independent items correlating to ‘experience of unemployment or unwilling job transfer’. Items independently correlating to ‘experience of a decrease in income’ were ‘diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, cataracta and/or others’ (1.34, 0.044); and ‘long-term (>1 month) hospital stay for treatment’ (1.58, <0.0001), and those correlating to ‘reduced social positivity and activity’ were ‘changes in appearance after oral corticosteroids’ (1.35, 0.026); and ‘bias for intractable and uncommon diseases from others’ (1.51, 0.002; see online supplementary table S2). Overall, these multivariate regression models picked out similar items to those exhibited univariate correlations with social disadvantages (the last paragraph and table 1).

bmjopen-2016-013278supp_table2.pdf (86.7KB, pdf)

Clinical parameters and correlations with social disadvantages

The backgrounds of the 917 patients and correlations of clinical parameters with the experience of social disadvantages (in applicable patients) are shown in table 2.

In 680 patients who received income from employment, the clinical parameters that exhibited significant positive correlations (p<0.0001, r≥0.15) with ‘experience of unemployment or unwilling job transfer’ and with ‘experience of a decrease in income’ were identical; these were: thymectomy; severity at worst condition (MGFA classification, bulbar symptoms, QMG); severity at current condition (QMG, MGC); peak dose of PSL and duration of PSL ≥20 mg/day. Conversely, achieving MM or better-5 mg at 1 and 4 years into treatment and at present exhibited significant negative correlations (p<0.0001, r≤−0.15).

In the 917 patients, the clinical parameters that exhibited significant positive correlations (p<0.0001, r≥0.15) with ‘reduced social positivity and activity’ were: female sex; severity at worst condition (MGFA classification, QMG); severity at current condition (QMG, MGC) and duration of PSL≥20 mg/day. Achieving MM or better-5 mg at any time point exhibited a significant negative correlation (p<0.0001, r≤−0.15) to this adverse effect.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses using the clinical parameters as variables did not function well (goodness of fit: χ2 statistic (Hosmer-Lemeshow test) p=0.11, Cox and Snell's pseudo R2=0.28 for ‘unemployment or unwilling job transfer’; 0.10, 0.18 for ‘experience of a decrease in income’ and 0.15, 0.26 for ‘reduced social positivity and activity’; see online supplementary table S3). These models failed to pick out most of the parameters that exhibited univariate correlations with social disadvantages (the last paragraph and table 2). Thus, we avoided employing the results of multivariate logistic regression models on discussing correlations of particular clinical parameters to the experience of social disadvantages.

bmjopen-2016-013278supp_table3.pdf (87.9KB, pdf)

In addition, to elucidate which time point of achieving MM or better-5 mg was most significant in inhibiting each of these social disadvantages, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed using parameters that showed negative correlations as variables. We found that ‘at 4 years into treatment’ was the most significant time point for achieving MM or better-5 mg in regard to inhibiting ‘experience of unemployment or unwilling job transfer’ (OR 0.61, p=0.03), ‘experience of a decrease in income’ (0.61, 0.04) and “reduced social positivity and activity” (0.49, 0.005).

Current MG-QOL15-J scores correlated positively with each of these social disadvantages (underlined in table 2), suggesting that the current HRQOL of the patients was worse with such experiences.

Discussion

The questionnaire results demonstrated that unemployment or an unwilling job transfer after MG onset was experienced by 31.3% of the patients, and a decrease in income was experienced by 35.9%, among whom 47.1% reported a decrease in total income of more than 50%. In a large German MG cohort, 21.0% of the patients experienced hardships in their jobs, and 28.3% were forced to retire early due to MG.9 In a study in Thailand, the unemployment rate among patients with MG was 26–58%, and reduced income was seen in 43–48%.10 In a community-based survey of Australian patients with MG, 39.4% had been forced to stop working due to MG, and 19.4% had to change their occupation.13 Only 40.6% of that cohort were working at the time of the survey, and the rest were unable to work due to the effects of the disease.13 Although the socioeconomic environments of these patients most likely differ to some degree, no substantial differences were observed in the frequency of such disadvantages between these countries. Therefore, a substantial number of patients with MG are burdened with socioeconomic disadvantages. MG may not be a major public health problem in terms of the number of patients affected; however, in terms of chronic problems due to its lifelong status, MG may have a substantial impact both on the patients themselves and on the community.9

The causes of these social disadvantages perceived by the patients themselves included bias from others, as well as an insufficient control of symptoms and long-term treatment (hospital stay >1 month and visiting the hospital for years). In many instances, the manifestations of MG are much more evident to the patient than to others, and appear to be frequently misunderstood.20 Fatigue is a very common symptom in MG, and this can be misinterpreted for laziness in the context of the workplace. Among individuals who have work demands and other responsibilities, such underestimations of MG symptoms interfere with performing social needs.9 11 Efforts must be made to help patients with MG achieve early improvement and return to a normal lifestyle as soon as possible.3 4 6 Efforts must also be made to better inform the public (particularly employers) about the characteristics of MG symptoms, as fluctuating weakness with fatigability which can be often underestimated at the workplace.

Participation in work is important because of the financial resources and access to benefits that jobs provide (eg, health insurance and welfare), and also because of a person's sense of self-respect, social network and feelings of usefulness and satisfaction.21 22 While at work, individuals are stimulated by physical and mental activities.9 Job loss is reportedly associated with worse self-perceived HRQOL and increased adverse health behaviours.22 In the patients with MG in the present study, experiences of unemployment or unwilling job transfers were consistently significantly correlated with the perception of reduced social positivity and low HRQOL scores. Adjustments in the workplace, as well as adequate therapy, are therefore important for patients with MG.9

Physical disability is naturally linked to occupational status and the likelihood of losing one's job. However, among the clinical parameters taken from examinations and patient records in this study, both severity of illness (worst and current status) and dose of oral steroids (peak dose of PSL and duration of PSL≥20 mg/day) were positively correlated with ‘unemployment or an unwilling job transfer’ and ‘a decrease in income’. Such associations could not be demonstrated in the present multivariate logistic regression probably due to poor model fit, but are consistent with previous reports in which both severity of illness and dose of oral steroids were the most significant factors negatively affecting patients' HRQOL.3 4 The severity of the disease tends to affect personal mobility, while the dose of oral steroids tends to affect social mobility;4 both of these disadvantages naturally lead to unemployment and a decrease in income.

On the other hand, strangely, thymectomy appeared to positively correlate with both ‘unemployment or an unwilling job transfer’ and ‘a decrease in income’. These unexpected associations were most likely due to correlations between thymectomy and other disadvantage-promoting factors such as ‘long-term (>1 month) hospital stay for treatment’ (r=0.27, p<0.0001), peak dose of PSL (r=0.37, p<0.0001) and duration of PSL≥20 mg/day (r=0.37, p<0.0001; Spearman rank correlation). These correlations might have arisen from previous treatment methods in some Japanese institutions in which thymectomy was often followed by high-dose oral steroid therapy using dose escalation and de-escalation. In actuality, performing thymectomy itself is considered to have no direct effect on HRQOL,10–12 or the social disadvantages of patients with MG.

Achieving MM or better-5 mg most likely enables patients to live a normal lifestyle without having to worry about complications resulting from steroids,3 4 and the achievement of such status negatively correlates with social disadvantages. Interestingly, at 1, 2 and 4 years into treatment and at present, 4 years into treatment appeared to be the most significant time point for inhibiting social disadvantages. The critical time for control of MG is reported to encompass the first several years after onset,2 and the first 4 years or so into treatment may be a permissible limit to achieve sufficient disease control that leads to a good long-term condition. Alternatively, for employers, a permissible employment time for patients who have uncontrolled illness and/or are experiencing treatment-related side effects may be limited to the first several years after disease onset. In any case, an early return to a normal lifestyle at least within the first several years of treatment may be important.

Among all patients, 49.0% answered that their ‘social positivity and activity was reduced’, and the self-perceived main causes included ‘depressive state, changes in mood or character after oral corticosteroids’, and ‘changes in appearance after oral corticosteroids’. The most significant clinical factor promoting a depressive state in patients with MG is reportedly an insufficient reduction in the dose of long-term oral steroids.16 It is probable that in the patients taking high doses of oral steroids, the problems in appearance and depressive state negatively affect personal relationships, positive thinking and social activities.4 Therefore, for long-term use, oral corticosteroids should be given at the lowest possible dose.3 4 16 23 Bias from others and female sex were also associated with decreased social positivity. Therefore, adequate social support, public acceptance and understanding may be highly beneficial in improving life circumstances among patients with MG.9 11

This study was limited by the facts that a part of clinical factors about participants was retrospectively obtained, that in some patients MGFA classifications and postintervention status were recreated by a review of clinical data, and that the study was dependent on patients' self-reported data. Whether employment status actually was affected at the time when MG was more severe and patients on more medication could not be addressed. It should be also noted that correlation levels of social disadvantages to the question items and clinical factors for MG were statistically significant but generally low. Naturally, other factors (eg, careers and experiences of job and educational backgrounds) probably had more significant effects on social activities and disadvantages, which should be taken into consideration when interpreting the present results.

In conclusion, although this study did have some limitations, among patients with MG receiving income from employment in Japan, unemployment or an unwilling job transfer after MG onset was experienced by 31.3%, and a decrease in income by 35.9%, among whom 47.1% experienced a decrease in total income of more than 50%. Among all patients with MG, 49.0% perceived a reduction in their social positivity. Both severity of illness and the way of treatment affected such disadvantages. An early return to a normal lifestyle without corticosteroid complications (eg, MM or better-5 mg) is therefore considered a major factor inhibiting such disadvantages. It is also important that employers and co-workers have better informed perceptions about MG, and that patients' workplace or living surroundings help accommodate MG symptoms.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr M Motomura and Dr H Shiraishi (Department of Neurology and Strokology, Nagasaki University Hospital), Dr Y Shimizu and Dr R Ikeguchi (Department of Neurology, Tokyo Women's Medical University) for collecting the patient data. This work was supported by the Japan MG Registry study group.

Footnotes

Contributors: YN, HM, TI, NK, MM, MA and KU were involved in study concept and design. YN, HM, TI, DY, ET, NM, YS, TK, AU, NK, MM, SK, HS, MA and KU were involved in acquisition of data. YN, HM, TI, DY, ET, NM, YS, TK, AU, NK, MM, SK, HS, MA and KU were involved in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. YN, HM, TI, DY, ET, NM, YS, TK, AU, NK, MM, SK, HS, MA and KU were involved in final approval of the version to be published. YN, HM, TI, MA and KU obtained funding and were involved in study supervision.

Funding: This work was supported by the Japan MG Registry study group.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study protocols were approved by the ethics committees of each participating institution.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Gilhus NE. Autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Expert Rev Neurother 2009;9:351–8. 10.1586/14737175.9.3.351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grob D, Brunner N, Namba T et al. Lifetime course of myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2008;37:141–9. 10.1002/mus.20950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masuda M, Utsugisawa K, Suzuki S et al. The MG-QOL15 Japanese version: validation and associations with clinical factors. Muscle Nerve 2012;46:166–73. 10.1002/mus.23398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Utsugisawa K, Suzuki S, Nagane Y et al. Health-related quality-of-life and treatment targets in myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2014;50:493–500. 10.1002/mus.24213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pascuzzi RM, Coslett HB, Johns TR. Long-term corticosteroid treatment of myasthenia gravis: report of 116 patients. Ann Neurol 1984;15:291–8. 10.1002/ana.410150316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders DB, Evoli A. Immunosuppressive therapies in myasthenia gravis. Autoimmunity 2010;43:428–35. 10.3109/08916930903518107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Padua L, Evoli A, Aprile I et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with myasthenia gravis and the relationship between patient-oriented assessment and conventional measurements. Neurol Sci 2001;22:363–9. 10.1007/s100720100066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul RH, Nash JM, Cohen RA et al. Quality of life and well-being of patients with myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2001;24:512–16. 10.1002/mus.1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Twork S, Wiesmeth S, Klewer J et al. Quality of life and life circumstances in German myasthenia gravis patients. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:129 10.1186/1477-7525-8-129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulkantrakorn K, Sawanyawisuth K, Tiamkao S. Factors correlating quality of life in patients with myasthenia gravis. Neurol Sci 2010;31:571–3. 10.1007/s10072-010-0285-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basta IZ, Pekmezović TD, Perić SZ et al. Assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with myasthenia gravis in Belgrade (Serbia). Neurol Sci 2012;33:1375–81. 10.1007/s10072-012-1170-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boldingh MI, Dekker L, Maniaol AH et al. An up-date on health-related quality of life in myasthenia gravis -results from population based cohorts. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015;13:115 10.1186/s12955-015-0298-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blum S, Lee D, Gillis D et al. Clinical features and impact of myasthenia gravis disease in Australian patients. J Clin Neurosci 2015;22:1164–9. 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.01.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burns TM, Conaway MR, Cutter GR et al. Less is more, or almost as much: a 15-item quality-of-life instrument for myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2008;38:957–63. 10.1002/mus.21053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burns TM, Grouse CK, Conaway MR et al. Construct and concurrent validation of the MG-QOL15 in the practice setting. Muscle Nerve 2010;41:219–26. 10.1002/mus.21609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki Y, Utsugisawa K, Suzuki S et al. Factors associated with depressive state in patients with myasthenia gravis: a multicenter cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000313 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaretzki A III, Barohn RJ, Ernstoff RM et al. Myasthenia gravis: recommendations for clinical research standards. Task Force of the Medical Scientific Advisory Board of the Myasthenia Gravis Foundation of America. Neurology 2000;55:16–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burns TM, Conaway MR, Cutter GR et al. Construction of an efficient evaluative instrument for myasthenia gravis: the MG composite. Muscle Nerve 2008;38:1553–62. 10.1002/mus.21185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burns TM, Conaway M, Sanders DB et al. The MG composite: A valid and reliable outcome measure for myasthenia gravis. Neurology 2010;74:1434–40. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dc1b1e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burns TM. History of outcome measures for myasthenia gravis. Muscle Nerve 2010;42:5–13. 10.1002/mus.21713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gignac MA, Lacaille D, Beaton DE et al. Striking a balance: work-health-personal life conflict in women and men with arthritis and its association with work outcomes. J Occup Rehabil 2014;24:573–84. 10.1007/s10926-013-9490-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Hiele K, van Gorp DA, Heerings MA et al. The MS@Work study: a 3-year prospective observational study on factors involved with work participation in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. BMC Neurol 2015;15:134 10.1186/s12883-015-0375-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagane Y, Suzuki S, Suzuki N et al. Early aggressive treatment strategy against myasthenia gravis. Eur Neurol 2011;65:16–22. 10.1159/000322497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-013278supp_table1.pdf (48.9KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013278supp_table2.pdf (86.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-013278supp_table3.pdf (87.9KB, pdf)