Abstract

Aims

The aim of this study was to compare adherence and persistence in patients who add ezetimibe to statin therapy as a separate pill combination (SPC) or fixed dose combination (FDC).

Method

This is a retrospective cohort study of prescription data conducted in an Australian health dataset. Two cohorts were identified: those dispensed statins and subsequently ezetimibe as either SPC or FDC. We compared adherence to combination therapy using the medication possession ratio (MPR), multivariate linear and logistic regression. Persistence to initial combination medicines and any lipid‐lowering therapies were analysed using Kaplan Meyer survival and Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

A total of 3651 people initiated ezetimibe SPC and 5740 ezetimibe FDC. There was no significant difference in adherence with mean MPRs: ezetimibe SPC = 0.99 (95% confidence interval 0.98–1.01) and FDC = 0.97 (95% CI 0.95–0.99). One year persistence rates to initial combination medicines were ezetimibe SPC 49.1% vs. FDC 62.4%; hazard ratio (HR) = 1.81 (95% CI 1.76–1.90). However, persistence to any lipid‐lowering therapy was higher in those initiating ezetimibe SPC = 84.9% vs. FDC = 76%; HR = 0.62 (95% CI 0.55–0.72). One year persistence rates to any two lipid‐lowering medicines were similar: ezetimibe SPC 65.2% and FDC 65%.

Conclusion

In this study FDCs have little impact on either adherence or persistence to combination lipid‐lowering therapy in people who have been taking statins. The benefit of higher persistence to FDCs in first episode of treatment with initial medicines is debatable as persistence to dual therapy was similar in both cohorts.

Keywords: adherence, fixed‐dose combinations, hyperlipidaemia, persistence

What is Already Known about this Subject

One reason for combining two or more medicines into one pill, an FDC, is to improve medication adherence.

Prior research suggests FDC formulations improve adherence and persistence to combination lipid‐lowering therapies.

What this Study Adds

Contrary to previous US and Australian research, this study suggests that FDC formulations do not significantly improve adherence or persistence to dual lipid lowering therapy.

Table of Links

This Table lists key ligands in this article that are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 1.

Introduction

The health benefits of long‐term treatment with lipid‐lowering therapy, including statins, have been well documented 2, 3. In Australia, studies using different methods report varying levels of patient adherence and persistence to statins and other lipid‐lowering medicines 4, 5, 6. A survey of Australian general practice found that in those prescribed statin therapy, 40% were not achieving target cholesterol levels 7. In patients who require multiple lipid‐lowering therapies, the concern is that increasing pill burden and cost will further compromise adherence to or persistence with these chronic therapies 8. As a result, fixed dose combinations (FDCs) and more recently co‐packaged products of ezetimibe and statins have been developed and marketed in Australia and many other countries.

The availability of FDCs internationally has grown significantly over the past 20 years. Between 1990 and 2013 the US Federal Drug Administration approved 131 new FDCs; 35 of these have been approved for cardiovascular conditions. Many of these new FDCs contain active ingredients that have previously been approved and widely used as individual medicines 9.

As FDCs do not provide any clinical benefit over the individual medicines taken together, determining their value in improving adherence and persistence is important, not only from a patient perspective but also for the pharmaceutical industry, health regulators, funders and insurers. The funder perspective is particularly relevant in Australia as the subsidized price paid for many FDC medicines may be higher than the equivalent separate pill combinations (SPC) 10. The Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee, tasked with valuing subsidized medicines in Australia, is required to assess evidence of any claimed improvement in compliance associated with FDC medicines 11, 12. Cost is also a concern in other countries such as the USA where FDCs may cost more than the equivalent SPCs 13.

A number of studies have concluded that FDCs improve adherence compared to SPCs of lipid‐lowering therapy 14, 15, 16 and several other chronic therapies including combinations of antihypertensive medicines 17, 18, 19, 20, 21. Contrary to the findings of these studies, the UK National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care 22 concluded in their review that there was not convincing evidence that changes in formulation alone improved adherence.

FDCs have also been shown to improve persistence, or length of time on treatment, in individual studies involving combinations of cardiovascular therapies 23, 24, 25. However one meta‐analysis 17 reported no significant improvements in persistence or blood pressure in patients taking FDCs of antihypertensive medicines compared to patients taking the equivalent SPCs.

In studies comparing persistence between FDCs and SPCs, persistence to formulation is usually measured rather than persistence to a therapeutic class of medicines 21, 23, 25. This is likely to underestimate the length of overall treatment in chronic conditions as people switch add and cease medications for a variety of reasons 5. Another concern when analysing adherence based on prescription refills relates to the method of assigning medication coverage to multiple prescriptions over a set time period. Separate prescriptions are not always dispensed on the same day resulting in days of coverage that may not correspond exactly. In comparative studies involving FDCs and SPCs, this staggered dispensing of separate prescriptions around the beginning and end of set time periods may introduce a small bias 26, that must be addressed in study design.

The aim of this study was to compare adherence and persistence in patients who added ezetimibe to their statin therapy as either an SPC or FDC. To address the methodological issues we measured adherence and persistence separately; assessing adherence over a flexible time period determined by the first and last dispensing dates within the follow‐up period. Because lipid‐lowering medicines are predominantly long‐term preventative therapies, we measured persistence to both initial ezetimibe combinations and persistence to any lipid‐lowering therapies.

Methods

Data source

Prescription dispensing data from the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS), which subsidizes medicines for all Australians, were analysed. The PBS dataset contains patient information including age, gender, concession status and prescriber specialty. Concessional beneficiaries include pensioners, seniors (over 65), veterans, and health or disability pensioners; other residents are considered general beneficiaries. Prescription information on date of supply, individual medicine item codes mapped to Anatomical Therapeutic Classification (ATC) codes 27, quantity supplied per prescription, benefit paid and patient contribution are also available. In 2015 the PBS patient contribution or co‐payment was $6.10 per prescription for concessional and $37.70 for general beneficiaries. Individuals and families may qualify for the ‘safety net’ when their co‐payments total $366 (concessional) or $1453.90 (general) within a calendar year. Having reached the safety net, their co‐payments reduce substantially for all remaining prescriptions: free of charge for concession card holders and $6.10 for general beneficiaries 28. Since June 2012, information on all prescriptions, including those priced under the general co‐payment level, have been recorded, resulting in complete capture of all PBS prescriptions dispensed. This is relevant because prior studies involving PBS medicines priced under the general co‐payment have been restricted to the concessional population only 29.

Ethical considerations

The design and methods for this study were approved by the Commonwealth Department of Human Services (DHS) External Request Evaluation Committee for analysis of PBS data. All analyses were conducted using de‐identified data and in accordance with DHS Privacy Policy.

Study design and population

A retrospective cohort study was conducted in the complete PBS dataset to identify people who initiated either ezetimibe SPC or ezetimibe FDC in the period from 1 April to 30 September 2013. Initiation to ezetimibe (index date) was determined on the basis of no prior PBS prescription for any medicines containing ezetimibe since 2004. People who were dispensed three or more statin prescriptions in the 12 months prior to initiating ezetimibe SPC or ezetimibe FDC were identified as the study population. Obtaining a minimum of three prior statin prescriptions corresponds with the minimum recommended time to assess individual patient response to statin therapy and conforms with the PBS eligibility criteria for subsidized use of ezetimibe in Australia 30. In addition, to be eligible for the ezetimibe SPC cohort, combination therapy was deemed to start if a statin prescription was dispensed on the same day as the initial ezetimibe prescription or within the subsequent 31 days. The dose prescribed for both statins and ezetimibe was assumed to be one tablet taken daily 31, thus the quantity of tablets supplied in each prescription equalled days of supply.

At the time of study entry in 2013, ezetimibe 10 mg was available as a separate pill or a FDC with simvastatin 10, 20, 40 and 80 mg. Other statins included in the eligible SPC cohort were atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, fluvastatin and pravastatin. Co‐packaged ezetimibe and atorvastatin became available in Australia in 2014 and was included along with fibrates, bile acid sequestrants as in‐class lipid‐lowering therapies in the persistence follow‐up period.

Outcomes

We measured both adherence and persistence separately, consistent with methodological recommendations for assessing medication taking behaviour in chronic conditions 32. Adherence refers to the taking of medication in accordance with prescriber recommendations regarding timing and dose; and persistence refers to the time period over which a patient continues treatment from initiation to cessation 33, 34, 35. To measure adherence, we calculated individual medication possession ratios (MPR) during the 6 months following initiation of ezetimibe SPC or ezetimibe FDC. The MPR was calculated by dividing the number of days of medication supplied (less the days supplied in the last refill) by the number of days between the first and last refill in the follow‐up period 36. This method, sometimes referred to as the MPR modified 33, 35 or prescription‐based proportion of days covered (PDC) 37 assesses intensity of drug use between the first and last dispensing dates in the follow‐up period. This modified MPR does not assess persistence or length of treatment.

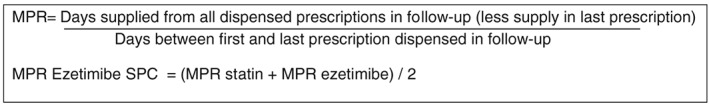

An MPR value of one represents complete medication coverage or full adherence to the study medicines, and can be analysed as a continuous variable or a dichotomous variable based on a pre‐specified threshold. The MPR may also be higher than one when people fill prescriptions earlier than required. MPRs greater than 1.2 can be referred to as ‘overadherence’ 33. In this study patients were considered adherent if their MPR was greater than or equal to 0.8. This threshold is often arbitrarily applied 36; however, in statin use it is supported by a US study that found MPRs less than 0.8 to be predictive of an increased risk of disease‐related hospitalization 38. As this was a comparative study of adherence to regimens of ezetimibe FDC (one pill) versus ezetimibe SPC (two pills), individual adherence to the SPC regimen was the average of their statin and ezetimibe MPRs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Formula for calculation of MPR

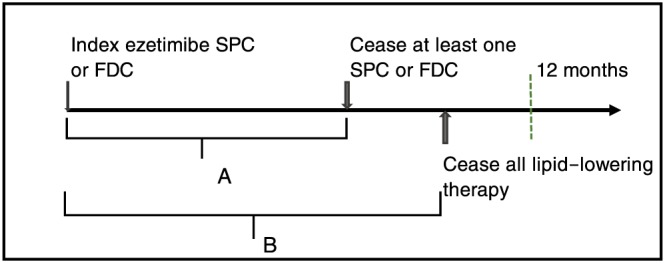

For the persistence studies, prescription records for all lipid‐lowering medicines dispensed following initiation to ezetimibe were obtained for a minimum of 12 months follow‐up. Persistence was then calculated in two ways (Figure 2).

Persistence was calculated as initial combination medicines where cessation was defined as a gap of 60 days or more following exhaustion of the days supplied for all previous dispensings of the same medicine. For people who initiated ezetimibe SPC, length of treatment to the statin component was calculated from the date of the first prescription (dispensed on or within 31 days of the ezetimibe index date) to last statin dispensing without a gap of 60 days or more. The shorter of the two lengths of treatment (ezetimibe and statin measured separately) was considered the time patients were persistent to initial ezetimibe SPC therapy.

Persistence to any lipid‐lowering therapy was calculated as the time between index date and the last dispensing for any lipid‐lowering medicines without a break of 60 days or more. In all analyses, patients were censored when they received their last prescription within 90 days (one prescription supply plus 60 days) from end of follow‐up.

Death data were not available in the PBS dataset. In the absence of this, a sensitivity analysis was undertaken censoring people who ceased all PBS medicines within the 3 months following cessation of the study medicines 39.

Figure 2.

Diagram of persistence to initial combination medicines and persistence to any lipid‐lowering therapy: (A) Persistence to the two initial combination medicines without a break of 60 days or more. (B) Persistence to any lipid‐lowering therapy without a break of 60 days or more

Statistical analysis

The following baseline characteristics were determined at the time patients initiated ezetimibe (index date): age; gender; concession status (concessional or general beneficiary); prescriber (specialist physician or general practitioner); patients qualifying for the safety net in the 6 months either side of the index date; the number of co‐dispensed PBS medicines; the number of comorbidities based on the RxRisk‐V index and medicines co‐dispensed on the index date 40; and number of prescriptions and adherence (MPR) to statins in the 12 months prior to ezetimibe initiation. Because mental illness has been shown to be associated with poor adherence and persistence 41, an additional variable was derived if patients were co‐dispensed any of the following medicines at index date: antipsychotics, antidepressants, benzodiazepines and lithium. Differences in baseline patient characteristics between the cohorts were compared using χ2 for differences in proportions and Wilcoxon rank sum tests for not normally distributed variables.

For the comparison of adherence between the SPC and FDC cohorts, the distribution of MPRs was compared using generalized linear regression. Logistic regression was used to compare the dichotomous outcome of adherent vs. not adherent cases. To compare persistence in the 12 months following initiation to ezetimibe SPC or FDC therapy, Kaplan Meier survival curves were compared using the Log‐rank test.

Baseline characteristics that differed between the two cohorts and considered potential confounders were included in the multivariate linear regression analysis for the comparison of adherence (MPR) and Cox proportional hazards analysis for the comparison of persistence. The proportional hazard assumption was checked by visual assessment of graphs plotting the log of the negative log of the estimated survivor function against log. All analyses were conducted in SAS Enterprise Guide version 5.1.

Results

There were 20 328 people who initiated ezetimibe in the 6‐month period from 1 April 2013 to 30 September 2013. Less than half of this population (n = 9391) initiated the combination of ezetimibe and a statin following receipt of three or more statin prescriptions in the previous 12 months.

The population that initiated ezetimibe SPC (n = 3651) therapy differed statistically from those who initiated ezetimibe FDC (n = 5740). They were slightly older, more likely to be male, had more comorbidities, more concomitant PBS medicines dispensed, and were more likely to be concessional beneficiaries and reach the safety net in the same 12‐month period. Prior MPR values for statin use were also higher in the cohort initiating ezetimibe SPCs and may predict higher adherence to any cardiovascular therapy. The greatest difference between the two cohorts was in relation to type of prescriber: general practitioners prescribed 90.5% of initial ezetimibe FDC prescriptions and 74.7% of initial ezetimibe SPC prescriptions (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study population

| Ezetimibe SPC (n = 3651) | Ezetimibe FDC (n = 5740) | P‐value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at index date | Median (IQR) | 65 (57, 72) | 63 (55, 70) | P < 0.001 |

| Gender = Male | n (%) | 2182 (59.8) | 3196 (55.7) | P < 0.001 |

| No. of comorbidities a | Median (IQR) | 4 (3, 6) | 4 (2, 5) | P < 0.001 |

| Concessional beneficiary b | n (%) | 2312 (63.3) | 3507 (61.1) | P = 0.02 |

| Reached PBS safety net threshold c | n (%) | 1605 (44.0) | 2008 (35.0) | P < 0.001 |

| GP prescriber of initial ezetimibe | n (%) | 2727 (74.7) | 5194 (90.5) | P < 0.001 |

| No. of statin prescriptions prior to index date | Median (IQR) | 11 (9, 12) | 10 (7, 12) | P < 0.001 |

| MPR for statin use in year prior to index date | Median (IQR) | 0.96 (0.84, 1.01) | 0.93 (0.76, 1.0) | P < 0.001 |

| No. of co‐dispensed medicines d | Median (IQR) | 4 (3, 7) | 4 (2, 6) | P < 0.001 |

| Co‐dispensed a medicine for mental illness | n (%) | 888 (24.3) | 1359 (23.7) | P = 0.4 |

P‐values < 0.05 are considered statistically significant

Comorbidities, number of comorbidities based on co‐dispensed medicines and RxRisk‐V index.

Concessional beneficiary, pensioners, seniors (>65 years), veterans, health and disability pensioners.

Safety‐net threshold, annual medicine co‐payment threshold where co‐payments were reduced to $0 for concessional and $6.10 general beneficiaries in 2015.

Co‐dispensed medicines, medicines dispensed in the 75th percentile refill interval with index ezetimibe.

GP, general medical practitioner; MPR, medication possession ratio

Adherence

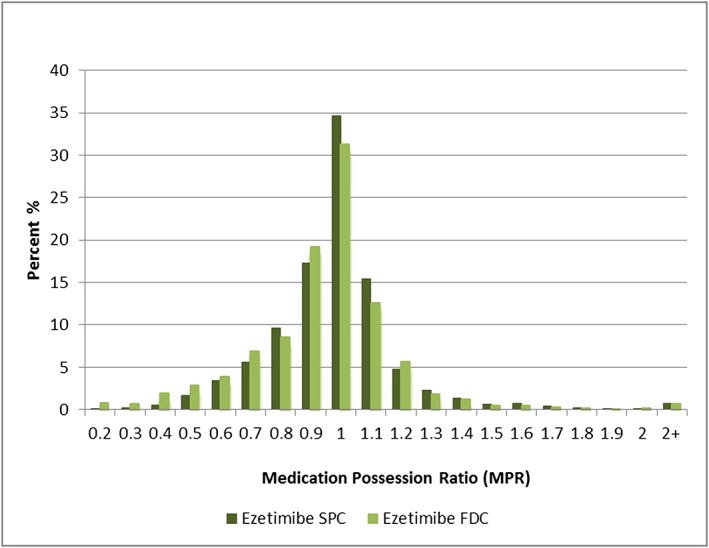

Both the unadjusted and adjusted comparisons of the distribution of MPRs were not significantly different between those taking ezetimibe SPC and ezetimibe FDC regimens (Table 2). Figure 3 shows the distribution of individual MPRs in both cohorts. Most people in both cohorts were adherent to initial combination therapy (SPC 83.6%, FDC 79.1%) and similar proportions in each cohort were ‘overadherent’ (SPC 7.2%, FDC 7.0%) with MPRs greater than 1.2.

Table 2.

Comparison of mean adherence (MPR) and proportion adherent in patients initiating ezetimibe SPC versus ezetimibe FDC

| Comparison measure | Ezetimibe SPC n = 3092 | Ezetimibe FDC n = 5219 | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MPR mean (95% CI) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | |

| Mean difference SPC − FDC (95% CI) Unadjusted | 0.022 (−0.01, 0.05) | P = 0.10 | |

| Mean difference SPC − FDC (95% CI) b Adjusted | 0.008 (−0.02, 0.04) | P = 0.63 | |

| Proportion adherent: MPR ≥ 0.8 | 83.6% | 79.1% | |

| Adherent odds ratio (95% CI) Unadjusted | 1.35 (1.23, 1.51) | ref | P < 0.001a |

| Adherent odds ratio (95% CI) b Adjusted | 1.11 (0.98, 1.26) | ref | P = 0.08 |

P‐values < 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Multivariate and logistic regression analyses includes adjustment for age, gender, number of comorbidities, safety net status, concessional beneficiary, GP prescriber, and MPR for prior statin use.

Ezetimibe FDC, cohort adding ezetimibe to simvastatin as a fixed dose combination formulation; Ezetimibe SPC, cohort adding ezetimibe as separate pill to any statin therapy; MPR, medication possession ratio

Figure 3.

Frequency distribution of individual medication possession ratios. Ezetimibe FDC, cohort adding ezetimibe to simvastatin as a fixed dose combination formulation. Ezetimibe SPC, cohort adding ezetimibe as separate pill to any statin therapy

Persistence

When persistence to initial combination medicines was measured, both unadjusted and adjusted persistence results were lower in people who initiated ezetimibe SPC compared to ezetimibe FDC during the first 12 months of treatment. Conversely, when persistence to any lipid‐lowering therapy was assessed, both unadjusted and adjusted results were higher in those who initiated the ezetimibe SPC (Table 3). A similar proportion of both cohorts – ezetimibe FDC (65.0%) and ezetimibe SPC (65.2%) – remained on at least two lipid‐lowering medicines for at 12 months. However, a higher proportion ceased all lipid‐lowering medicine in the ezetimibe FDC cohort (26.5%) compared to the ezetimibe SPC cohort (16.2%). The sensitivity analysis had no effect on the persistence results when all patients lost to follow‐up were censored in the analysis.

Table 3.

Proportion persisting at 52 weeks and comparison of risk of cessation to initial combination and any lipid‐lowering therapy between patients who initiated ezetimibe SPC vs. ezetimibe FDC

| Lipid‐lowering combination | Ezetimibe SPC (n = 3651) | Ezetimibe FDC (n = 5740) | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| % persisting with initial combination at 52 weeks | 49.1% | 64.4% | P < 0.001 (Log rank) |

| Risk of cessation, unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 1.63 (1.50, 1.74) | ref | P < 0.001 |

| Risk of cessation, adjusted a HR (95% CI) | 1.81 (1.76, 1.90) | ref | P < 0.001 |

| % persisting with any lipid‐lowering therapy at 52 weeks | 84.9% | 76.0% | P < 0.001 (Log rank) |

| Risk of cessation, unadjusted HR (95% CI) | 0.54 (0.51, 0.63) | ref | P < 0.001 |

| Risk of cessation, adjusted a HR (95% CI) | 0.63 (0.55, 0.72) | ref | P < 0.001 |

P‐values < 0.05 are considered statistically significant

Cox proportional hazard model adjusted for age, safety net status and GP prescriber.

Ezetimibe FDC, cohort adding ezetimibe to simvastatin as a fixed dose combination formulation; Ezetimibe SPC, cohort adding ezetimibe as separate pill to any statin therapy

Discussion

Unlike previous studies 14, 15, 16, we found no difference in adherence to either formulation of ezetimibe plus statin therapy. One other Australian study, Vytorin compliance study 1V, submitted to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee in 2014 16 and undertaken using a 10% sample of PBS data, claimed ezetimibe FDC increased adherence compared to ezetimibe SPC: mean MPRs were 0.81 and 0.71 respectively. This study measured adherence within individuals pre‐ and post‐switching from ezetimibe SPC to ezetimibe FDC in a small population (n = 305) who had MPRs less than 0.85 pre‐switch. Due to the pre‐post design, it is difficult to conclude whether the improvement in MPR post‐switch to ezetimibe FDC was attributable to the formulation or other factors such as positive clinical feedback and prescriber support during the medical consultation for the FDC prescription. The applicability of these results to the broader PBS population prescribed a combination of ezetimibe and statin was also limited due to the narrow inclusion criteria.

The findings from our study are also in contrast to two studies conducted in the USA that reported significantly higher adherence in those taking an FDC compared to SPCs of lipid‐lowering therapies 14, 15. In the US studies, the MPR was calculated differently, using set time periods as the denominator. As discussed earlier, MPRs calculated over set time periods may include periods when the initial combination of medicines were switched or ceased and can also bias MPR measures of multiple prescriptions dispensed on different days.

Overall our findings of high adherence to lipid‐lowering medicines in the Australian population are not dissimilar to those reported in a previous study of statin adherence based on PBS data 6. The cohort study of approximately 42 500 long‐term statin users, measured adherence rates based on an MPR calculated over a fixed time period of 24 months. They found 80% of concession card holders and 57% of general beneficiary patients were adherent using the MPR threshold of greater than or equal to 0.8.

Our results for persistence to first episode of treatment with index therapies favoured people taking the ezetimibe FDC, and are consistent with other persistence results from studies comparing FDCs with SPCs for cardiovascular conditions 18, 20, 23, 25. However, when we considered persistence to any two lipid‐lowering therapies, the proportion of people continuing dual lipid‐lowering therapy was similar in both cohorts. In addition, 10% more people stopped all lipid‐lowering therapy for 60 days or longer in the cohort initiating ezetimibe FDC. While it is not possible to know the reason for ceasing treatment in this study, one explanation may be the inability of patients on FDCs to independently stop taking one medicine at a time, resulting in the cessation of both medicines when only one is causing a problem.

The methods in this study do differ from other studies comparing adherence and persistence between FDCs and SPCs and are the likely reason for our differing results. Other studies have calculated MPRs and similar adherence measures over set time periods and do not consider therapeutic or in‐class switches in measures of persistence to chronic therapies 14, 15, 21, 23, 25. While it may be argued that a switch away from either formulation means that the initial formulations are no longer being compared, the strength of study designs that allow switching is that therapeutically appropriate persistence is considered, i.e. the proportion remaining on similar combination therapy, consistent with what occurs in practice.

The two populations dispensed ezetimibe SPC and FDC did differ significantly in this study. Patients in the SPC cohort were more likely to have their initial ezetimibe prescription written by a medical specialist instead of a general practitioner. This may indicate that those in the SPC cohort have more serious cardiovascular disease or risk factors. Severity of disease and other unknown factors associated with adherence such as smoking status and ethnicity 6, 42 were not accounted for in this study. However, we were able to adjust for the known confounders of age, gender, number of comorbidities, number of co‐dispensed medicines, socioeconomic status according to concessional status and type of prescriber.

This study was conducted in PBS data collected from the whole Australian population with complete capture of all prescriptions dispensed other than samples provided by industry or privately purchased prescriptions. We were able to confidently identify new users of ezetimibe who fill at least one subsidized prescription. Persons who were prescribed ezetimibe but did not fill a single prescription, sometimes referred to as primary non‐adherers, were also not accounted for in this study. The PBS dataset does not contain information on death or other loss to follow‐up; however, in a sensitivity analysis we imputed loss to follow‐up by using similar methods previously validated in Australian veterans' data 39 and found no effect on the primary persistence results.

Competing Interests

All authors have completed the unified competing interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi‐disclosure (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare this work was supported by an Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) centre for research excellence in post‐marketing surveillance of medicines and devices grant (GNT1040938). EER is supported by an NHMRC Fellowship (GNT1110139). NP is supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship (Grant Number GNT1035889). All authors declare no financial relationships with any organization that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years and no other activities or relationships that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Contributors

All authors participated in the research design, data analysis and interpretation, critical review and revision of the final manuscript. LB designed the research, analysed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript.

Bartlett, L. E. , Pratt, N. , and Roughead, E. E. (2017) Does tablet formulation alone improve adherence and persistence: a comparison of ezetimibe fixed dose combination versus ezetimibe separate pill combination?. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 83: 202–210. doi: 10.1111/bcp.13088.

Footnotes

Co‐dispensing is defined as the overlap of supply of PBS medicine(s) within the 75th percentile refill interval for each medicine.

References

- 1. Southan C, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Alexander SP, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2016: towards curated quantitative interactions between 1300 protein targets and 6000 ligands. Nucl Acids Res 2016; 44: D1054–D1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Taylor F, Huffman MD, Macedo AF, Moore THM, Burke M, Davey Smith G, et al. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 2013: CD004816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, McCagg A, White JA, Theroux P, et al. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 2387–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Simons LA, Ortiz M, Calcino G. Long term persistence with statin therapy – experience in Australia 2006–2010. Aust Fam Physician 2011; 40: 319–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Roughead EE, Vitry AI, Preiss AK, Barratt JD, Gilbert AL, Ryan P. Assessing overall duration of cardiovascular medicines in veterans with established cardiovascular disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2010; 17: 71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Warren JR, Falster MO, Fox D, Jorm L. Factors influencing adherence in long‐term use of statins. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2013; 22: 1298–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Webster RJ, Heeley EL, Peiris DP, Bayram C, Cass A, Patel AA. Gaps in cardiovascular risk management in Australian general practice. Med J Aust 2009; 191: 324–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Barkas F, Liberopoulos E, Elisaf M. Impact of compliance with antihypertensive and lipid lowering treatment on cardiovascular risk: benefits of fixed‐dose combinations. Hell J Athero 2013; 1: 18–25. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kararli T, Sedo K, Bossart J. Fixed‐dose combination products – a review. Drug Development and Delivery 2014; Available at http://www.drug‐dev.com/Main/Back‐Issues/FIXEDDOSE‐COMBINATIONS‐FixedDose‐Combination‐Produ‐673.aspx (last accessed 3 June 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clarke PM, Avery AB. Evaluating the costs and benefits of combination therapy. Med J Aust 2014; 200: 518–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Australian Government Department of Health . Compliance to Medicines Working Group Report to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee [Online]. Available at http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/publication/factsheets/shared/2010‐09‐20‐Compliance_to_Medicines_Working_Group_Report_to_PBAC (last accessed 1 September 2016).

- 12. Australian Government Department of Health . Guidelines for preparing submissions to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee [Online]. Available at https://pbac.pbs.gov.au/ (last accessed 1 September 2016).

- 13. Hong S, Wang J, Tang J. Dynamic view on affordability of fixed‐dose combination antihypertensive drug therapy. Am J Hypertens 2013; 26: 879–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamat SA, Bullano MF, Chang CL, Gandhi SK, Cziraky MJ. Adherence to single‐pill combination versus multiple‐pill combination lipid‐modifying therapy among patients with mixed dyslipidemia in a managed care population. Curr Med Res Opin 2011; 27: 961–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Balu S, Simko RJ, Quimbo RM, Cziraky MJ. Impact of fixed‐dose and multi‐pill combination dyslipidemia therapies on medication adherence and the economic burden of sub‐optimal adherence. Curr Med Res Opin 2009; 25: 2765–2775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee . Public Summary Document – November 2014 ezetimibe + simvastatin. 2014. Available at http://www.pbs.gov.au/industry/listing/elements/pbac‐meetings/psd/2014‐11/files/ezetimibe‐simvastatin‐psd‐11‐2014.pdf (last accessed 1 September 2016).

- 17. Gupta AK, Arshad S, Poulter NR. Compliance, safety, and effectiveness of fixed‐dose combinations of antihypertensive agents: a meta‐analysis. Hypertension 2010; 55: 399–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sherill B, Halpern M, Kahn S, Panjabi S. Single pill versus free equivalent combination therapies for hypertension: a meta‐analysis of health care costs and adherence. J Clin Hypertens 2011; 13: 898–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hussein MA, Chapman RH, Benner JS, Tang SS, Solomon HA, Joyce A, et al. Does a single‐pill antihypertensive/lipid‐lowering regimen improve adherence in US managed care enrolees? A non‐randomized, observational, retrospective study. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 2010; 10: 193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Machnicki G, Ong SH, Chen W, Wei ZJ, Kahler KH. Comparison of amlodipine/valsartan/hydrochlorothiazide single pill combination and free combination: adherence, persistence, healthcare utilization and costs. Curr Med Res Opin 2015; 31: 2287–2296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xie L, Frech‐Tamas F, Marrett E, Baser O. A medication adherence and persistence comparison of hypertensive patients treated with single‐, double‐ and triple‐pill combination therapy. Curr Med Res Opin 2014; 30: 2415–2422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nunes V, Neilson J, O'Flynn N, Calvert N, Kuntze S, Smithson H, et al Clinical guideline and evidence review for medicines adherence: involving patients on decisions about prescribing medicines and supporting adherence. London: National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care and Royal College of General Practitioners, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Simons LA, Ortiz M, Calcino G. Persistence with a single pill versus two pills of amlodipine and atorvastatin: the Australian experience, 2006–2010. Med J Aust 2011; 195: 134–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brixner DI, Jackson KC 2nd, Sheng X, Nelson RE, Keskinaslan A. Assessment of adherence, persistence, and costs among valsartan and hydrochlorothiazide retrospective cohorts in free‐ and fixed‐dose combinations. Curr Med Res Opin 2008; 24: 2597–2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang W, Chang J, Kahler KH, Fellers T, Orloff J, Wu EQ, et al. Evaluation of compliance and health care utilization in patients treated with single pill vs. free combination antihypertensives. Curr Med Res Opin 2010; 26: 2065–2076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arnet I, Abraham I, Messerli M, Hersberger KE. A method for calculating adherence to polypharmacy from dispensing data records. Int J Clin Pharm 2014; 36: 192–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. World Health Organisation . ATC Structure and Principles. Oslo: Norwegian Institute of Public Health, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Australian Government Department of Health . Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme 2015. Available at http://www.pbs.gov.au/info/about‐the‐pbs#What_are_the_current_patient_fees_and_charges (last accessed 1 September 2016).

- 29. Paige E, Kemp‐Casey A, Korda R, Banks E. Using Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme data for pharmacoepidemiological research: challenges and approaches. Public Health Res Pract 2015; 25: e2541546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Australian Government Department of Health . Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule [Online]. 2015. Available at http://www.pbs.gov.au/medicine/item/8757X (last accessed 1 September 2016).

- 31. Dohme, MS . Product Information: Vytorin. Therapuetic Goods Administration Product and Consumer Medicine Information, 2014. Available at https://www.ebs.tga.gov.au/ebs/picmi/picmirepository.nsf/PICMI?OpenForm&t=PI&q=Vytorin&r=http://www.pbs.gov.au/medicine/item/9484E (last accessed 1 September 2016).

- 32. Peterson AM, Nau DP, Cramer JA, Benner J, Gwadry‐Sridhar F, Nichol M. A checklist for medication compliance and persistence studies using retrospective databases. Value Health 2007; 10: 3–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Raebel MA, Schmittdiel J, Karter AJ, Konieczny JL, Steiner JF. Standardizing terminology and definitions of medication adherence and persistence in research employing electronic databases. Med Care 2013; 51: S11–S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cramer JA, Roy A, Burrell A, Fairchild CJ, Fuldeore MJ, Ollendorf DA, et al. Medication compliance and persistence: terminology and definitions. Value Health 2008; 11: 44–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hess LM, Raebel MA, Conner DA, Malone DC. Measurement of adherence in pharmacy administrative databases: a proposal for standard definitions and preferred measures. Ann Pharmacother 2006; 40: 1280–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andrade SE, Kahler KH, Frech F, Chan KA. Methods for evaluation of medication adherence and persistence using automated databases. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2006; 15: 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Choudhry NK, Shrank WH, Levin RL, Joy LL, Jan SA, Brookhart MA, et al. Measuring concurrent adherence to multiple related medications. Am J Manag Care 2009; 15: 457–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, Hudson TJ, West DS, Martin BC. Good and poor adherence: optimal cut‐point for adherence measures using administrative claims data. Curr Med Res Opin 2009; 25: 2303–2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mealing NM, Dobbins TA, Pearson S‐A. Validation and application of a death proxy in adult cancer patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012; 21: 742–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vitry A, Wong SA, Roughead EE, Ramsay E, Barratt J. Validity of medication based co‐morbidity indices in the Australian elderly population. Aust N Z J Public Health 2009; 33: 128–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tuppin P, Neumann A, Danchin N, Ricordeau P, De Peretti C, Allemand H. Patient characteristics associated with adherence to evidence based medications (EBM) and mortality after acute myocardial infarction (AMI): a nationwide French survey of administrative data. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 640.20038514 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Knott RJ, Petrie DJ, Heeley EL, Chalmers JP, Clarke PM. The effects of reduced copayments on discontinuation and adherence failure to statin medication in Australia. Health Policy 2015; 119: 620–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]