Abstract

Statement of the Problem:

Porcelain laminate veneer is an esthetic restoration used as an alternative to full veneer crowns and requires minimal tooth preparation. In restoration with porcelain laminate veneers, both the longevity of the laminate and conservation of the sound tooth structure are imperative.

Purpose:

The present study aimed to investigate the shear bond strength of porcelain laminates to prepared- and unprepared- anterior teeth in order to compare their longevity and success rate.

Materials and Method:

Thirty extracted maxillary central incisors were randomly divided into 3 groups regarding their preparation methods. The preparation methods were full-preparation in group A, full-preparation and finishing with fine diamond bur in group B, and no-preparation, only grinding with diamond bur in group C. After conditioning the teeth, ceramic veneers (IP S e.max) were silanated and then cemented with DuoLink luting cement. The shear bond strength was measured for each group and failure mode was determined by stereomicroscopic examination.

Results:

Group C exhibited the highest shear bond strength. The shear bond strength was significantly different between groups C and B (p< 0.05). However, the difference between group A and C was insignificant, as was the difference between group A and B (p> 0.05). Adhesion failure mode was found to be more common than the cohesive mode.

Conclusion:

Regarding the shear bond strength of unprepared anterior teeth to porcelain laminate veneers yielded by this study, no-preparation veneers might be used when the enamel is affected by wearing, trauma, or abrasion. It can also be used in patients who refuse the treatments which involve tooth reduction and preparation.

Keywords: Dental veneer , Dental porcelain , Dental laminate , Dental bonding , Shear strength , Tooth preparation

Introduction

Porcelain laminate veneer bonded to enamel was first described in the early 1980s.[1-2] It is an esthetic restoration which requires minimal tooth preparation and is applied as an alternative to full veneer crowns for treatment of enamel defects, discolored teeth, diastema, minor tooth wear and malposition, as well as large pulp cavities particularly in young patients.[3] Ceramic veneers can also be selected to restore the traumatized and fractured dentition.[4-5]

A clinical study is reported a 93% survival rates for ceramic veneers after 15 years[6] which is attributed to the conservation of tooth structure, reliable bonding to enamel, favorable esthetics, and color stability.[7] Yet, the long-term prognosis of ceramic veneer is influenced by various factors such as tooth surface and morphology, ceramic thickness, the type of employed cement, the aberrant function, and geometry of the preparation.[8] The prognosis of porcelain veneer can be decreased by many factors such as marginal discoloration, postoperative sensitivity, fracture, and debonding.[9] Since the high rate of failure in restorations is related to the large exposed dentin, the preparation technique is considered as the most determining factor for the longevity of porcelain laminate veneer.[10]

The three common failure types of porcelain laminate veneer are static, cohesive, and adhesive fractures. The static failure is defined as the fracture of a fragment of veneer while the remainder of the veneer remains intact on the tooth. The cohesive fracture is characterized by the loss of a piece of porcelain as a result of excessive functional or parafunctional loading. In the adhesive failure mode, the intact porcelain veneer debonds completely from the tooth.[11]

Three different conventional preparation designs for laminate veneer has been stated as window preparation, butt joint incisal preparation and incisal lapping preparation. In most indirect fabricated laminate veneer either a butt joint incisal design or an incisal approach is used.[12] In order to achieve an optimal bond with the porcelain laminate veneer as well as to decrease the stresses in the porcelain, the preparation should completely be ended in enamel.[9,13] Meanwhile, minimally invasive veneer preparation designs have become more popular.[14] The clinical discussions have lately focused on minimal-preparation to no-preparation veneers. As recommended by dental manufacturers and laboratories, no-preparation veneer is the ideal choice to conserve the tooth structure and to achieve the best esthetic results in comparison to conventional tooth preparation veneers. [15-15] No-preparation or minimally invasive veneers are ultra-thin or contact-lens thin veneers[17] with a thickness of 0.3-0.5 mm.[18-19]

The wide variety of tooth preparation methods has made them the most considerable factor for both clinicians and patients. The shear tests are most commonly employed to measure the bond strength of dental materials since they are easy-to-perform, require minimal equipment and preparation.[10] The aim of the present study was to evaluate the shear bond strength of porcelain laminate to prepared- and unprepared-anterior teeth in order to compare their longevity and success rate.

Materials and Method

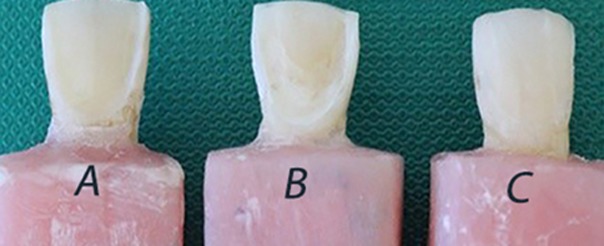

In this study, 30 extracted maxillary central incisors with completely intact roots and crowns, and homogeneous mesiodistal width and labio-palatal thickness were collected .These measurements were performed by gauge. They were all free of caries or restorations. The specimen were cleaned and stored in 0.01% thymol solution at room temperature. The teeth were randomly divided into 3 groups (n=10) based on the preparation methods of full-preparation (A), full preparation and finishing with fine diamond bur (B), and no-preparation but only grinding with coarse diamond bur (C) (Figure 1). The roots of specimens were embedded in auto polymerizing acrylic resin blocks of 1×0.5×0.5 inch. All the following procedures were performed only by one examiner.

Figure1.

Three different preparations: block A, B and C represents full preparation, full preparation & finishing and no preparation respectively.

Tooth preparation

To provide veneers with equal thickness, the reduction of facial surface and incisal edge was the same in both group A and B to provide veneers with equal thickness. The facial surface was reduced 0.3 mm at the cervical third and 0.5 mm at the middle and incisal third. For butt-joint incisal preparation, 0.5 mm was reduced in incisal edge using fissure diamond bur under water coolant. After each preparation, the bur was discarded and a new bur was used. In both groups, the finish lines were located facially to proximal contact. The cervical finish lines were established 1 mm above the cemento-enamel junction. Self-limiting depth- cutting burs of 0.3mm and 0.5mm were used to define the depth-cut and a chamfer diamond bur to refine the preparation. The prepared samples of group B were additionally smoothened with fine diamond finishing bur. The samples allocated in group C had no reduction, however; to obtain an optimal surface for bonding in this group, the teeth were grinded with coarse diamond bur to remove only the surface aprismatic enamel.

For all groups an impression was made for each prepared tooth with vinyl polysiloxane impression material (Panasil A-silicon; Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The impressions were then sent to a dental laboratory and were poured with a type IV dental stone. Porcelain veneer wax patterns with 1.5 mm increasing in incisal edge were fabricated for all groups with similar surface area. Then, they were heated in furnace at 800°C for 60 minutes, 600°C for 30 minutes, and 850°C for 60 minutes. The investment and an ingot of IPS e.max press were then transferred to the furnace (EP 500; IPS Empress, Ivoclar Vivadent, Schaan, Liechtenstein) and automatically pressed (930°C, 60 minutes, program 16).[10]

Bonding the ceramic veneers

All the prepared and unprepared teeth in all groups were cleaned with pumice slurry, rinsed, and dried. Then, the teeth were etched with 37% phosphoric acid (Scotchbond etchant gel; 3M ESPE) for 30 seconds, rinsed for 30 seconds, and carefully dried. Two coats of a One-Step Plus dental adhesive (Bisco; USA) were applied, gently air-dried, and light polymerized for 10 seconds.

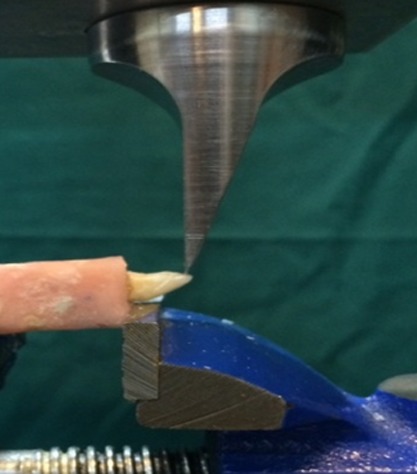

The porcelain veneers were etched with 9.5% buffered hydrofluoric acid gel (Porcelain Etchant; Bisco) for 90 seconds, rinsed with water, and carefully air-dried. Ceramic veneers were silanated (Bisco Porcelain Primer, USA) and then cemented by using DuoLink luting cement (Bisco; USA). The restorations were seated with finger pressure of only one examiner and light polymerized with the light intensity of 480nm and a power of 1100 mW/cm2 for 5 seconds. Then the excess cements were removed to simulate the real intraoral conditions. The specimens were polymerized for 40 seconds on all surfaces. The bonded specimens were stored at room temperature with 100% relative humidity before fracture test. Each specimen was mounted on a metal holder in the Instron universal testing machine (Figure 2). All the specimens in all groups were tightened and stabilized to ensure the loading pin was positioned properly on the ceramic veneer, i.e. 1 mm from the incisal edge and at 90° angle to the palatal surface of the teeth. The load was applied at a crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min until the failure occurred. The ultimate load leading to failure was recorded in Newton (N). The means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated. The failure modes were classified to cohesive and adhesive mode based on the fracture pattern observed under stereomicroscope at 20× magnification. [20-21]

Figure2.

Instron universal testing machine. inserting the relevant force on the palatal surface of specimen.

The statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS software, version 11 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, IL). The ANOVA test was used to analyze the differences in the mean level of shear bond strength among the three groups. Tukey’s HSD test was employed to evaluate any difference among the groups. p< 0.05 was adopted as statistical significance.

Results

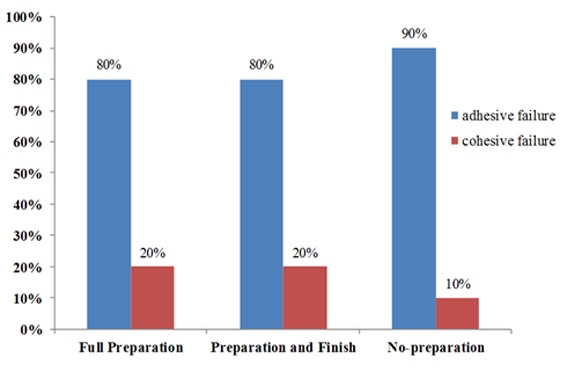

The mean levels of shear bond strength for the groups are summarized in Table 1 and Figure 3.

Table 1.

The mean shear bond strength in the study groups

| Method | Shear Bond Strength | Ln(SBS) | P-value* | p-value** |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Preparation | 66.9200 | 4.1335 | 0.018 | (prep)vs. (prep &finish): 0.655 |

| Preparation and Finish | 55.2300 | 3.9575 | (prep)vs. (no prep): 0.112 | |

| No-Preparation | 107.3800 | 4.5490 | (no prep)vs. (prep &finish): 0.017 |

Significance level set at p< 0.05

One-way ANOVA

Tukey’s HSD test

Figure3.

Comparing the two bond failure modes of study groups (%).

One-way ANOVA showed that the mean shear bond strength values were significantly different among the groups (p< 0.05). The highest shear bond strength was observed in group C, followed by A and B. Statistically significant difference was detected between group C and B (p< 0.05). However, the difference between group A and C and also between group A and B was statistically insignificant (p> 0.05).

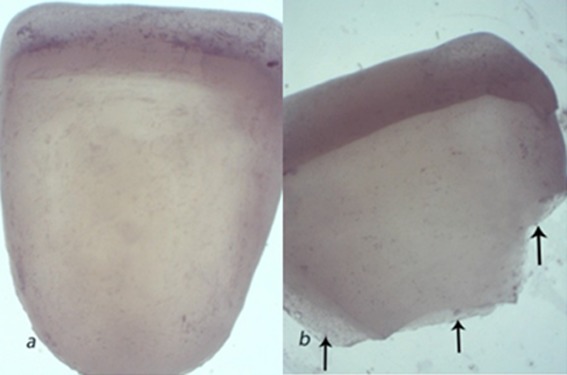

Figure 4a and 4b demonstrate the modes of failure. Adhesive failure mode was observed in 80% of specimens in groups A and B, and 90% of specimens in group C. Cohesive failure mode occurred in 20% of specimens in groups A and B, and 10% of those in group C.

Figure4.

Different modes of failure, a: Adhesive failure, b: Cohesive failure

Discussion

The present in vitro study used three different preparation methods and compared the fracture toughness of laminate porcelain veneer by measuring the shear bond strength. Based on the results of this study, no-preparation method yielded the highest shear bond strength. This result is in agreement with the results reported by Ozturk et al.[10] and Ge et al.[14] that the thicker the enamel, the more loads was necessary to cause catastrophic failure. Among the studied methods, no-preparation method preserved more enamel tissue than the other two methods. Presence of more enamel tissue increases the predictability and success of bonding.[20] Unfortunately, ideal and normal tooth structure may not be always present in clinical settings due to some conditions such as tooth wearing, age abrasion, and trauma. Therefore, conventional approach for tooth preparation results in more dentin exposure. In such cases, no-preparation method can be the best option to prevent dentin exposure and increasing the treatment success. Furthermore, temporary restorations are not required in no-preparation method and postoperative sensitivity unlikely occurs.[18] Current laboratory and technological advances allow producing an exceptionally thin veneer with porcelain of high strength which maintains its durability.[17,19,22] In addition to being easily bounded to the tooth, these thin veneers are superior esthetically. Moreover, their thickness and bulk is comfortable and unnoticeable for the patient and they do not alter the emergence profile. [17]

The current study revealed that full preparation method resulted in higher shear bond strength compared to preparation and finishing method. The result of this study was in line with that of the previous studies which showed the formation of micromechanical retention and resin micro tag within the enamel surface was the fundamental mechanism of adhesion.[23-24] Although, the difference between these methods was insignificant, it seems that finishing can reduce the micromechanical retention and consequently decrease the bond strength.

According to the findings of this study, the frequency of adhesion failure was more than cohesive mode in all the study groups. It was in agreement with what was reported by Ozturk et al.[10] and Lambade et al., but in contrast with Germain et al.’s[11] study in which cohesive failure was profound. Such a difference in failure mode might be due to the difference in the adhesion resin, maintenance condition, preparation procedures, and the type of porcelain used in each study. Enamel imparts stiffness to the tooth much like a metal coping does for a metal-ceramic crown. Removal of the enamel negatively affects the stress-strain distribution of the subsequent veneer. This leads to an increase in flexure under load and ultimately cohesive fracture.

Cohesive fracture of porcelain was rarely observed in the three study groups. The mean shear bond strength of adhesion system used in this study (26.26 MPa)[25] was far less than lithium-disilicate porcelain IPS e.max Press fracture toughness (mean= 350MPa).[26] This difference in porcelain and adhesion system can cause more adhesive rather than cohesive failure in laminate veneer.

The findings of this study are based on an in vitro experimental design; thus, the results may cautiously be generalized to oral (in vivo) environment. A porcelain laminate in the oral environment is subjected to several kinds of chemothermal factors such as rapid changes of pH, hot and cold beverages, mechanical forces, and pulp pressure. Although, in vivo trials are the ultimate tests to evaluate the performance of laminate veneer, presence of many involving variables makes it difficult to differentiate the true reason of failure.

Conclusion

With respect to the findings of the current study, it can be concluded that no-preparation method provides the highest shear bond strength for porcelain veneer laminate. Hence, no-preparation veneers can be suggested to use when the enamel is affected by wearing, trauma, and abrasion as well as in patients who refuse any tooth reduction or preparation.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the Vice-chancellery of Shiraz University of Medical Science for supporting this research. The authors would like to thanks Dr. Shahram Hamedani (DDS, MSc) from Dental Research Development Center for his suggestions and editorial assistance and Dr. Mehrdad Vosoughi (PhD) for the statistical analysis.

Conflict of Interest:None to declare.

References

- 1.Horn HR. Porcelain laminate veneers bonded to etched enamel. Dent Clin North Am. 1983; 27: 671–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calamia JR. Etched porcelain facial veneers: a new treatment modality based on scientific and clinical evidence. N Y J Dent. 1983; 53: 255–259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gür E, Kesim B. Porcelain laminate veneers (in Turkish) Cumhuriyet University Dentistry Faculty Journal. 2004; 7:72–79. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferrari M, Patroni S, Balleri P. Measurement of enamel thickness in relation to reduction for etched laminate veneers. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1992; 12: 407–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Christensen GJ. Veneering of teeth. State of the art. Dent Clin North Am. 1985; 29: 373–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friedman MJ. A 15-year review of porcelain veneer failure--a clinician's observations. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 1998; 19: 625–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edelhoff D, Sorensen JA. Tooth structure removal associated with various preparation designs for anterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 2002; 87: 503–509. doi: 10.1067/mpr.2002.124094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B, Lambrechts P, Vanherle G. Porcelain veneers: a review of the literature. J Dent. 2000; 28: 163–177. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(99)00066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.JB S, Roobins JW, Hilton TJ, Schwartz R. Porcelain veneer In: Grisham B, editor. Fundamentals of operative dentistry: a contemporary approach. 4th ed. Quintessence publishing Co, inc: China; 2013. pp. 463–487. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Öztürk E, Bolay Ş, Hickel R, Ilie N. Shear bond strength of porcelain laminate veneers to enamel, dentine and enamel-dentine complex bonded with different adhesive luting systems. J Dent. 2013; 41: 97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.St Germain HA Jr, St Germain TH. Shear bond strength of porcelain veneers rebonded to enamel. Oper Dent. 2015; 40: E112–21. doi: 10.2341/14-123-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oheymann H, Edward J, Swift J, Vritter A. Art and sience operative dentistry. 6th ed. Elsevier Mosbey: Canada; 2013. pp. 316–319. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Troedson M, Dérand T. Shear stresses in the adhesive layer under porcelain veneers. A finite element method study. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998; 56: 257–262. doi: 10.1080/000163598428419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ge C, Green CC, Sederstrom D, McLaren EA, White SN. Effect of porcelain and enamel thickness on porcelain veneer failure loads in vitro. J Prosthet Dent. 2014; 111: 380–387. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein MB. No-prep/minimal-prep: the perils of oversimplification. Dent Today. 2007; 26:10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dura thin veneers. Available at: [http://www.durathinve-neers.com/ ]

- 17.Lumineer no prep technique for porcelain laminate veneer. Dent- mat corporation. Available at: [http://www.luminessair.com/ ]

- 18.Strassler HE. Minimally invasive porcelain veneers: indications for a conservative esthetic dentistry treatment modality. Gen Dent. 2007; 55: 686–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malcmacher L. No-preparation porcelain veneers--back to the future! . Dent Today. 2005;24:86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmidt KK, Chiayabutr Y, Phillips KM, Kois JC. Influence of preparation design and existing condition of tooth structure on load to failure of ceramic laminate veneers. J Prosthet Dent. 2011; 105: 374–382. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(11)60077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castelnuovo J, Tjan AH, Phillips K, Nicholls JI, Kois JC. Fracture load and mode of failure of ceramic veneers with different preparations. J Prosthet Dent. 2000; 83: 171–180. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3913(00)80009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cattell MJ, Knowles JC, Clarke RL, Lynch E. The biaxial flexural strength of two pressable ceramic systems. J Dent. 1999; 27: 183–196. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(98)00047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swift EJ Jr, Perdigão J, Heymann HO. Bonding to enamel and dentin: a brief history and state of the art, 1995. Quintessence Int. 1995; 26: 95–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gwinnett AJ, Matsui A. A study of enamel adhesives. The physical relationship between enamel and adhesive. Arch Oral Biol. 1967; 12: 1615–1620. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(67)90195-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lambade DP, Gundawar SM, Radke UM. Evaluation of adhesive bonding of lithium disilicate ceramic material with duel cured resin luting agents. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015; 9: ZC01–ZC05. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/9582.5512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakaguchi RL, Powers JM. Craig's restorative dental materials. 13th ed. Elsevier Mosbey: United State; 2012. pp. 259–264. [Google Scholar]