Abstract

The congenital gingival granular cell tumor (CGCT), also as known as congenital epulis, is an unusual benign oral mucosal lesion in newborns. A two-day-old female patient was admitted to the Department of Pediatric Dentistry at Gulhane Medical Academy, Ankara, Turkey with her family, and an intraoral examination showed a CGCT located in the buccal region of the maxillary right first primary molar. In this report, we present a case of CGCT in a newborn.

Keywords: Congenital epulis , Newman tumor , Oral mucosa

Introduction

The congenital gingival granular cell tumor (CGCT) is rare and found mainly in the gingival mucosa, most commonly in the anterior maxillary alveolar ridge. This tumor, which is also known as congenital epulis, congenital myoblastoma or Neumann's tumor, is benign and does not recur or metastasize.[1-2] It appears at birth and occurs more frequently in females than in males.[3] Although the exact histogenesis of this tumor is unknown, it is thought to originate from epithelial, undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, pericytes, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and nerve-related cells.[4-5] Management of CGCTs includes surgical excision to facilitate feeding and respiration.[6] The aim of this case report is to describe the treatment of a 2-day-old female patient who had a CGCT.

Case Report

A two-day-old female patient was admitted to the Department of Pediatric Dentistry at Gulhane Medical Academy because of swelling of the gums in her upper jaw. She had no medical problems and had been born by natural childbirth. Intraoral examination revealed a polypoid lesion (diameter 0.4 to 0.7 cm) in the area of the maxillary right first primary molar (Figure 1). The tumor had a smooth surface, was pedunculated, and was the same color as the surrounding oral mucosa. No abnormality was detected in neighboring tissue.

Figure1.

Initial appearance of the tumor before surgical excision.

Following consultation with the maxillofacial surgery department, surgical excision under general anesthesia was planned to solve the infant's feeding problems. The operation was performed on the 12th postnatal day and a biopsy specimen was sent for histopathological examination. S100 antibody was used in the immuno-histochemical investigation. The histopathological examination of the tumor confirmed that it was a CGCT (Figure 2). Wound healing was observed at the two-week follow up, and there was no abnormality in the area of the surgery (Figure 3).

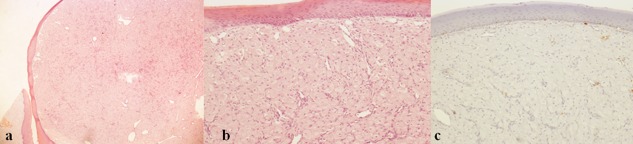

Figure2.

a: Histologic sections showed subepithelial, unencapsulated but well-demarcated tumor (20xH&E). b: At higher magnification, it was seen that the tumor was composed of plump-polygonal shaped cells with large-pale granular cytoplasm and uniform small round nuclei. Note that there was no overlying pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia (100xH&E). c: İmmunohistochemically, the tumor cells were negative for S-100 protein unlike its adult counterpart (100xİmmunohistochemistery-S100 protein).

Figure3.

Healing area after two weeks.

Discussion

CGCTs, initially defined as "congenital epulis" by Ernst Christian Neumann in 1871, are rare benign mesenchymal tumors.[7] It is reported that these tumors are found three times more frequently in the maxillary anterior region than in the mandibular region. CGCTs often originate from the gingiva of the anterior maxillary alveolar ridge.[1,8-9]

CGCTs are seen most frequently in newborn females (F/M 8:1) as a result of the stimulation of the intrauterine endogenous hormone.[5,8] The tumor is often single but it has been reported to be multiple in 5 to 16% of cases. Multiple tumors appear to occur mainly in the maxilla or mandible and have rarely been reported in the tongue. The diameter of the tumor can range from 0.1 to 4cm. The diameter of the largest tumor reported was 7.5cm.[9-10]

GCTCs, in the clinical differential diagnosis, include teratomas, congenital dermoid cysts, congenital fibrosarcomas, hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, leiomyomas, rabdomyomas, heterotopic gastrointestinal cysts, congenital cystic choristomas, and congenital lipomas. CGCTs appear as normal-colored mucosa, while hemangiomas and lymphangiomas have a red or dark blue area that is spongy on palpation. Findings from palpation for fluctuation and Doppler ultrasound may be used for definitive diagnosis of CGCTs and cystic lesions. Radiological examination for GCTCs includes a margin of soft tissue that is not related to hard tissue. This is done mainly to differentiate GCGTs from solid tissue tumors, especially to eliminate the suspicion of malignancy.[11]

In terms of histology, CGCTs look like adult granular cell tumors. The tumor cells are polygonal with large granular cytoplasms and small eccentric nuclei. There is no mitosis and necrosis, but there is a network of capillaries among the tumor cells. Pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia is not found in CGCTs overlying the multilayered squamous epithelium. It is thought that this tumor has undifferentiated mesenchymal cells, fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, histiocytes, Schwann cells or odontogenic epithelial progenitor cells.[12]

When the tumor increases in size, it can cause feeding and respiration problems. Therefore, surgical excision is required without delay. No recurrences have been observed in cases where a CGCT has been completely removed.[5,13] In our case, the tumor was removed completely.

Conclusion

CGCTs are rare benign tumors, and surgical resection is required to prevent feeding and respiration problems. Histopathologic examination is a critical component in the diagnostic process.

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: None to declare.

References

- 1.Inan M, Yalçin O, Pul M. Congenital fibrous epulis in the infant. Yonsei Med J. 2002; 43: 675–677. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2002.43.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loyola AM, Gatti AF, Pinto DS*Jr, Mesquita RA. Alveolar and extra-alveolar granular cell lesions of the newborn: report of case and review of literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997; 84: 668–671. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(97)90370-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernhoft CH, Gilhuus-Moe O, Bang G. Congenital epulis in the newborn. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1987; 13: 25–29. doi: 10.1016/0165-5876(87)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dash JK, Sahoo PK, Das SN. Congenital granular cell lesion "congenital epulis"--report of a case. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2004; 22: 63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godra A, D'Cruz CA, Labat MF, Isaacson G. Pathologic quiz case: a newborn with a midline buccal mucosa mass. Congenital gingival granular cell tumor (congenital epulis) Arch Pathol Lab Med 2004; 128: 585–586. doi: 10.5858/2004-128-585-PQCANW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zerener T, Sencimen M, Altun C, Altug HA. Congenital granular cell tumor in newborn. Eur J Dent. 2013; 7: 497–499. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.120651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neumann E. Ein fall von congenitaler epulis. Arch Heilkd. 1871; 12:189–190. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bilen BT, Alaybeyoğlu N, Arslan A, Türkmen E, Aslan S, Celik M. Obstructive congenital gingival granular cell tumour. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2004; 68: 1567–1571. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lack EE, Worsham GF, Callihan MD, Crawford BE, Vawter GF. Gingival granula cell tumors of the newborn (congenital "epulis"): a clinical and pathologic study of 21 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1981; 5: 37–46. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charrier JB, Droullé P, Vignaud JM, Chassagne JF, Stricker M. Obstructive congenital gingival granular cell tumor. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2003; 112: 388–391. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Regezi JA, Sciubba JJ, Jordan RCK. Oral pathology: Clinical pathologic correlations. 5th ed. Elsevier Saunders: St Louis; 2008. pp. 168–170. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshi N, Tsuura Y, Watanabe K, Suzuki T, Kasukawa R, Suzuki T. Expression of immunoreactivities to 75 kDa nerve growth factor receptor, trk geneproduct and phosphotyrosine in granular cell tumors. Pathol Int. 1995; 45: 748–756. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1995.tb03392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tokar B, Boneval C, Mirapoğlu S, Tetikkurt S, Aksöyek S, Salman T, et al. Congenital granular-cell tumor of the gingiva. Pediatr Surg Int. 1998;13:594–596. doi: 10.1007/s003830050412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]