Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Abortion laws are proliferating in the United States, but little is known about their impact on abortion providers. In 2011, North Carolina instituted the Woman’s Right to Know (WRTK) Act, which mandates a 24-hour waiting period and counseling with state-prescribed information prior to abortion. We performed a qualitative study to explore the experiences of abortion providers practicing under this law.

STUDY DESIGN

We conducted semi-structured interviews with 31 abortion providers (17 physicians, 9 nurses, 1 physician assistant, 1 counselor, and 3 clinic administrators) in North Carolina. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Interview transcripts were analyzed using a grounded theory approach. We identified emergent themes, coded all transcripts, and developed a thematic framework.

RESULTS

Two major themes define provider experiences with the WRTK law: provider objections / challenges and provider adaptations. Most providers described the law in negative terms, though providers varied in the extent to which they were affected. Many providers described extensive alterations in clinic practices to balance compliance with minimization of burdens for patients. Providers indicated that biased language and inappropriate content in counseling can negatively impact the patient-physician relationship by interfering with trust and rapport. Most providers developed verbal strategies to mitigate the emotional impacts for patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Abortion providers in North Carolina perceive WRTK to have a negative impact on their clinical practice. Compliance is burdensome, and providers perceive potential harm to patients. The overall impact of WRTK is shaped by interaction between the requirements of the law and the adaptations providers make in order to comply with the law while continuing to provide comprehensive abortion care.

Keywords: Abortion, abortion providers, abortion legislation, abortion restrictions

INTRODUCTION

Abortion laws are proliferating throughout the United States. In 2013, 22 states passed 70 laws restricting abortion.[1] Targeted regulations of abortion providers (TRAP laws) have been enacted in 26 states, and in states with the most extreme laws, multiple clinics have closed.[1] Clinics that remain open must find ways to comply with laws that regulate care for abortion patients. TRAP laws frequently mandate actions and speech outside the boundaries of standard clinical care, including medically unnecessary waiting periods, ultrasound requirements, and scripted counseling.[2, 3]

Professional organizations, including the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, have criticized such laws.[4, 5] Many abortion providers already labor under stressful conditions of stigma[6], threat of violence[7], and institutional barriers to abortion provision.[8] Where TRAP laws exist, providers face unique challenges in providing comprehensive reproductive care. TRAP laws can impact the number of abortion providers within a state or region,[9] and can contribute to a stigmatizing and threatening atmosphere.[10]

In October 2011, HB 854, the “Woman’s Right To Know Act” (WRTK), went into effect in North Carolina. Similar to laws in 37 other states, WRTK mandates a 24-hour waiting period after informed consent before an abortion can be performed. Content of the counseling is partially dictated by the state and contains statements regarding the potential harms of abortion, risks of carrying a pregnancy to term, pregnancy alternatives, the obligations of the father, and the availability of assistance from the state if the pregnancy is continued. Initially, the law mandated that an ultrasound be performed and the images be described to the woman; this portion of the law was enjoined and later overturned. There are no provisions for providers to use discretion in consideration of specific patient circumstances. We performed a qualitative study of abortion providers in North Carolina to investigate how providers perceived the law and how compliance affected their abortion practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We recruited physicians, physician assistants, nurses, counselors, and clinic administrators involved in abortion provision in North Carolina. Providers were eligible if they worked under the WRTK law and had prior experience practicing in a less restrictive environment. A list of known North Carolina abortion providers was compiled from the National Abortion Federation database, online search, and the researchers’ professional networks. Providers were contacted by letter, phone, or email and invited to participate. We also employed a snowball sampling strategy in which participants were asked to share information about the study with colleagues, and those contacts were invited to participate as well. Sample size was determined by saturation of themes. Participants were compensated for their time with a US $20 gift card.

We conducted semi-structured, open-ended interviews with providers. The interview guide covered topics including the provider’s professional history, current practice characteristics, personal experiences in providing care under the law, and perceptions of how the law affected their patients. The interview guide was pilot tested with out-of-state abortion providers prior to study enrollment. Interviews lasted 35–90 minutes (average 60 minutes) and were conducted by two members of the research staff (MB and LB) with training in qualitative interview techniques. Neither interviewer had a prior professional relationship with any participants. With one exception, interviews were conducted in person and were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Transcripts and field notes were examined using an inductive iterative approach based on grounded theory [11, 12] to identify themes related to providers’ experiences. The research team read all transcripts and field notes to identify emergent themes. We defined themes broadly to capture the depth and variation across provider experience and developed a coding structure and dictionary. Interview transcripts were analyzed and coded in Dedoose software. Each interview transcript was coded by two members of the research team blinded to the other’s work; this coding was reviewed by the PI (RJM) to check for agreement. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus. After coding was complete, we identified several themes that were most frequently discussed by providers and assembled them into the conceptual model described below. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Thomas Jefferson University.

3. RESULTS

We contacted the 16 known freestanding abortion clinics in North Carolina. Providers from eight of these clinics participated in our study. Five facilities did not respond and three declined to participate, citing policies that prohibited employees from participating in research. A total of ten providers affiliated with three hospitals known to provide abortion services were contacted directly; nine of these providers participated. We interviewed a total of 31 providers. (Table 1) Participants were affiliated with 11 distinct clinical practices. Participants practiced in 8 counties (of 100 total) in North Carolina. Several providers were affiliated with more than one clinical site.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Characteristic | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Provider Professions | |

| Physician | 17 (55%) |

| OB-Gyn | 15 (88%)a |

| Family Medicine | 2 (12%)a |

| Nurse | 9 (29%) |

| Physician Assistant | 1 (<1%) |

| Counselor | 1 (<1%) |

| Administrator | 3 (9%) |

| Practice Type | |

| Hospital Based | 9 (29%) |

| Free-standing clinic | 22 (71%) |

| Solo Practice | 9 (41%)b |

| Group Practice/ Clinic | 13 (59%)b |

| Percentage of providers’ practice devoted to abortion provision | |

| <25% | 11 (35%) |

| 25–50% | 7 (23%) |

| 50–75% | 1 (<1%) |

| 75–100% | 10 (32%) |

| 100% | 2 (7%) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 23 (74%) |

| Male | 8 (26%) |

| Years in practice providing abortion | |

| <10 | 16 (52%) |

| 11–20 | 5 (16%) |

| 21 – 35 | 5 (16%) |

| >35 | 5 (16%) |

% of physicians;

% of free standing clinic

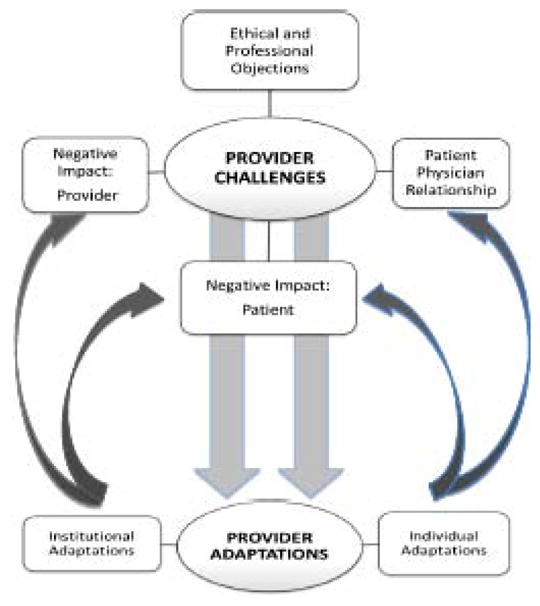

Two overarching themes emerged from our data. We summarize these themes as ‘provider objections /challenges’ and ‘provider adaptations.’ (Figure 1) Our conceptual model describes the relationship between the challenges WRTK presented and providers’ strategies and adaptations for achieving compliance. We identified overlap and interaction between challenges and adaptations. Providers adapted their practice not only to comply with the law, but also to ameliorate its effects on patients. Therefore, providers’ overall experience was defined both by the requirements of the law itself and by effects of the adaptations they made on the institutional and individual level to protect their patients’ interests. The major themes and subthemes are described below.

Figure 1. Abortion provider experience practicing under the Women’s Right to Know Act.

This figure illustrates our conceptual model describing provider experience as an interaction of the direct effects of the WRTK law and the impact of the adaptations made to comply with the law and accommodate patients.

3.1 Provider Objections and Challenges

All participants had negative opinions of the WRTK law. Some providers experienced a major negative impact, while others described it as less burdensome. A few providers also identified unexpected positive benefits of the law for select patients. Five distinct subthemes emerged concerning provider objections to the law. (Additional illustrative quotes, Table 2)

TABLE 2.

Provider Objections and Challenges: Sub-themes and illustrative data

| Ethical and Professional Objections | |

| Perceived intentions | “It seems very clearly to be designed to shame women and guilt them out of deciding to have an abortion.” (103, MD) “I think it tends towards limiting access and I think that’s what its purpose was.” (201, RN) |

| Impact on Provider | |

| Cost and staffing | “It was a huge financial impact. We’re adding a whole twenty-seven hours of nurse time that we had not budgetedIt’s like a whole other three-quarters FTE.” (302, Administrator) |

| Stress | “I actually had to take some medical leave time after we were able to institute this law. It was just – it was super stressful. ” (303, Administrator) |

| Normalization | “I was in [another state] where none of this existed, so when I first got here it just seemed absolutely insane. It’s still insane but I’m just so accustomed to it now that I’m less offended by it, which isn’t good but it’s just normal.” (113, MD) |

| Impact on Patient | |

| Patients’ negative opinions of counseling | “With the child support thing they’ll laugh and say, ‘You think the state’s really going to help me? Are they going to buy diapers?’… That’s when they kind of snicker, like, ‘Really? There is help available? You’re really going to help me?’” (204, RN) “They’re frustrated. Some of our patients vocalize that they just feel like the counseling is ridiculous, that they feel almost insulted by it, that it really has no place in their care.” (115, MD) |

| No impact on decision | “I don’t think the twenty-four hour waiting period makes any difference …The idea of that was for people to be sure. I think that’s crazy thinking. They were sure when they called.” (201, RN) |

| Unanticipated positive effects | “There was a woman…I was able to make this woman feel, like, totally okay, that we weren’t monsters, and that abortion is a really common, safe thing. That part has been the silver lining, but do I feel like that’s a good reason to have a 24-hour consent, no I don’t.” (209, RN) |

| Patient-Physician Relationship | |

| Interferes with rapport | “It’s this forced language that I don’t necessarily agree with, I think that affects the relationship with doctors and patients.” (113, MD) “The scripting really impedes the patient physician relationship… It just seems to challenge the initiation of a provider-patient rapport, in a situation where you need to engender a lot of trust quickly.” (110, MD) |

3.1.1 Ethical and Professional Objections

Providers objected to the WRTK law as an unreasonable intrusion into the practice of medicine. They felt abortion was targeted above and beyond other areas of medicine. Providers also resented the regulation of medical practice by politicians with little medical knowledge. Most felt that while the law was purportedly intended to improve patient knowledge and safety, its actual purpose was to discourage women from obtaining abortion by restricting access or providing misleading information.

“None of what they are proposing correlates with increased safety or efficacy of the procedure… It’s just purely political because they’re trying to restrict abortion access.” (101, MD)

The required counseling did not replace the clinical informed consent procedures already in place. All providers continued to perform a separate, standard clinical informed consent and the same in-person counseling regarding abortion that they had been performing prior to the law.

3.1.2 Negative Impact on Providers

Most providers indicated that complying with the law created a substantial institutional burden. Providers often reported increased costs, generally due to the effort and resources needed to provide the required counseling. Before WRTK, many sites employed trained but unlicensed staff to perform counseling. After WRTK, costs were greatly increased by the requirement that counseling be performed by licensed medical professionals (RN, NP, PA, or MD).

“They’ve had to hire more nurses…we’ve had to increase staffing and increase hours… it’s, like, 40 hours a week that there’s consent calls being done.” (210, RN)

Academic sites with residents and fellows did not experience an increase in costs, but increased physician hours to provide counseling. Providers felt this increase in cost and hours was needlessly burdensome, as the mandated changes in counseling did not improve patient safety or care. A minority of providers characterized the law as merely an administrative hassle. Sites reporting minimal impact were generally freestanding practices that provided a low volume of abortion care in combination with other gynecology services.

Several providers reported physical and emotional stress relating to the law. Stress originated from three main sources: the process of figuring out the logistics of compliance, a sensation of increased scrutiny with fear of consequences for inadequate compliance, and the act of providing the mandatory counseling itself. Stress related to counseling was often attributed to the perception of negative impacts on patients. The providers’ frustration and stress were heightened by their belief that the law did not matter for the provision of safe abortion care.

“All of them increase the stress on providers. They’re just laws that can catch me accidentally doing something wrong legally, not doing anything wrong medically.” (116, MD)

3.1.3 Negative Impact on the Patient-Provider Relationship

Providers were concerned that compliance with the law could interfere with their relationships with patients in several ways. Providers reported that patients could perceive providers as denying care or imposing barriers to care. Providers also feared that the content and process of the counseling could give patients the impression that the provider was questioning their decision or did not support them in their choice. They devoted time and effort to clarify that these were state requirements.

“I think that’s really demeaning to women that it’s like ‘Oh, you’ve made this decision? Well, let me question you about it 6,000 different ways.’ So I do think people interpret it as us wanting them to change their minds.” (210, RN)

Providers also struggled with the standardized content of the counseling. Requirements to review information that they considered inappropriate, irrelevant, or harmful interfered with establishing trust and rapport. The standardized nature of the content was of particular concern for patients terminating pregnancies for reasons of fetal anomalies, maternal health, or rape.

“Well, I’ve had at least two teenagers who were raped. The last thing they need to hear any details about [is] the father of the baby.” (108, MD)

3.1.4 Negative Impact on Patient

Most providers felt that the WRTK law was a barrier to abortion access. Occasionally, difficulty in coordinating counseling or the waiting period itself resulted in patients having procedures at later gestational ages.

“I’m seeing the same person on my schedule for weeks in a row because we haven’t been able to get in touch with them…they’re going from having a procedure in their first term to a mid-trimester abortion.” (210, RN)

Despite delays, providers believed that the law prevented few women from actually obtaining an abortion. No provider recalled a case where a patient seemed to change her mind about having an abortion as a result of the law.

Many providers recalled occasions when patients had negative reactions to the counseling procedure. Providers felt that some patients suffered emotional distress related to the counseling. This was especially common for patients who were terminating pregnancies for reasons of fetal anomalies, maternal health, or rape.

“There was a patient who – she just found out that her precious baby had a life threatening problem and decided to terminate and then they had to listen to this ridiculous script …She started crying and just saying, ‘I can’t do that. I can’t believe I have to go through this again.’” (208, RN)

Providers did note that the law occasionally had unanticipated positive effects for patients, generally when counseling provided the opportunity to reassure an anxious patient in advance of her abortion appointment.

3.1.5 Normalization

Providers described “getting used to” the law and having its requirements come to seem routine over time. Despite their continued objections, in daily work it was no longer perceived as exceptional.

3.2 Adaptations to the Law

All providers had to make changes to their practice to comply with the law, although the extent of these adaptations varied. Variation in adaptation stemmed from differences in practice structure and resources, as well as the desire to minimize impact on patients. Adaptations occurred at the institutional level, with changes to clinical flow, staffing, and documentation. Providers also described individual changes and strategies employed in patient interactions. (Additional illustrative quotes, Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Provider Adaptations to WRTK: Sub-themes and Illustrative Data

| Institutional Adaptations | |

| Schedule and protocol changes | “Our practice had to change in that it requires almost a full day of physicians’ time to make phone calls.” (108, MD) |

| Insulating patients from costs and inconvenience | “We don’t charge these people for 24-hour consents because that’s not right. That’s not fair, to pass that burden along to our patients.” (207, RN) “I don’t want to have that requirement impose an unnecessary burden on women already in a tough situation.” (103, MD) |

| Individual Adaptations | |

| Distancing | “I will stop them and I will say, ‘I just want you to know that this is a legal document that I’m required to read by law. Please don’t mistake this for my personal judgment towards you. I’m here to offer you whatever support and help that you feel like you need.’” (207, RN) |

| Apologizing | “I think we apologize to patients and we say ‘We’re sorry we’re required by the state to do this.’” (113, MD) |

| Expressed opinion | “I refuse to just read the consent and not tell them which part I think is true and which part isn’t.”(111, MD) “I make it clear I think it’s bullshit.” (113, MD) “I think for the patient it kind of denigrates it a little bit so that maybe they can also sneer at it. I’m sneering at it is basically what I’m doing. And I’m going to let them sneer at it too.” (109, MD) “Depending on what they say, I’m like, ‘I know, I’m with you.’” (206, RN) |

3.2.1 Institutional Adaptation

Providers noted that the ultrasound provision of WRTK would have been extremely burdensome to both patients and providers. Providers had planned for extensive changes: restructuring appointment schedules, accommodating multiple clinic visits for each patient, and training or increasing staff. As this portion of the law was enjoined, these adaptations were not actually enacted by most providers. Therefore, the mandated counseling with 24-hour waiting period was the aspect of the law that required the most clinical restructuring.

Most providers had previously offered abortion care within a single office visit. WRTK required that patients come for two visits or that providers perform the required counseling by phone prior to the abortion visit. The majority of providers offered phone counseling, which required staffing and bureaucratic changes. At freestanding, solo practices, hours were extended, or counseling was provided outside of office hours and the office setting.

“The vast majority of our calls come outside of office hours…We developed a scheduling form. We keep these at home, we keep them with us in my car…and so they call, I can get a call anytime day or night…we know we have it documented.” (106, MD)

High-volume providers commonly restructured their staffing; nurses were hired to perform phone counseling, often in a call center. In centers where residents and fellows provided counseling, time was diverted from other clinical and academic duties to perform phone calls. For most providers, phone counseling allowed them to provide more efficient care and this was perceived as less burdensome to patients than requiring two clinic visits.

While WRTK compliance was associated with increased cost, providers did not want to pass this cost onto patients. Institutional adaptations were aimed at keeping costs low, and other sources of revenue were sought to cover this gap.

“Instead of passing it on to our patients, we fundraised additional dollars….to help support it.” (302, Administrator)

3.2.2 Individual Adaptations in Patient Interactions

Providers who performed patient counseling described strategies for minimizing its potential negative impacts on patients. Providers often prefaced the counseling with statements which distanced themselves from the content, or apologized for what they were about to say.

“I start off with almost a disclaimer…explain that there’s a state law and I’m going to read them a hospital interpretation of that.” (110, MD)

Some providers reported saying all of the state-mandated content, but also shared their own contrary opinions regarding the content. Some providers expressed agreement with patients’ negative statements regarding the counseling, which helped build rapport with the patient.

“I let them know I’m on their side. Basically I don’t mind annotating or throwing in my two cents worth on some of this stuff.” (106, MD)

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative investigation of abortion providers’ experiences practicing under the WRTK Act in North Carolina, most providers felt that WRTK complicated the provision of abortion without any benefit to patient safety or knowledge. Providers viewed the law as intrusive and politically motivated. This negative response stemmed from providers’ ethical and professional objections to the law, challenges faced in compliance, and concern about potential impacts on patients. Providers’ overall experience with the law was influenced by the interaction between these challenges and the adaptations made to comply with the law while still providing compassionate abortion care.

Many providers made efforts to minimize the impact of the law on patients. Institutional adaptations such as the implementation of phone counseling were partially motivated by provider needs but were largely structured to maintain accessibility for patients. While these adaptations helped to maintain patient access, they also led to increased cost and workloads. This suggests a shift in the burden of the law from the patient to provider, resulting in a professional and personal strain that was uncomfortable for some providers. Normalization may blind providers to the ongoing negative impact of the law.

Providers also attempted to minimize the emotional impact on patients. Providers were especially concerned that standardized counseling was inappropriate for patients terminating desired pregnancies or for victims of rape, though the potential impact on the provider-patient relationship was noted for all subsets of patients. The individual adaptations providers employed to distance themselves from the law and align themselves with patients’ interests might help to preserve the relationship in the face of these challenges. These techniques also grant an outlet for individual expression. Providers were able to comply with the law by expressing the required content, but also stating their opinion or opposing medical views as needed in a given situation. Legal scholarship has posited that TRAP laws may represent an unethical intrusion into the patient-provider relationship or an unconstitutional version of compelled speech.[13–15] As such, the finding that the patient-provider relationship is in fact compromised in certain situations may give insight into a novel approach to countering these laws.

Strengths of our study include the diverse sample, which included providers of various professional backgrounds and from multiple practice environments. By including providers who had experience in less restrictive environments, we were able to contextualize the WRTK law along a spectrum of legislative environments. Because we did not assess patient experience directly, more research is necessary to understand the impact of WRTK on patients. As these laws proliferate, further research will be needed to investigate the impact on patients. Future research should also explore the legal and ethical implications of interference in the patient-provider relationship.

This study provides important insight into the effect of TRAP laws on abortion providers. North Carolina’s WRTK law is less burdensome than TRAP laws in other states. While less likely to lead to clinic closures and access barriers as seen in some states, WRTK still has significant impact on providers and patients. Evaluating the impact of laws on the patients, the providers, and the patient-provider relationship is critical for ensuring high quality patient care.

IMPLICATIONS.

Laws like WRTK are burdensome for providers. Providers adapt their clinical practices not only to comply with laws, but also to minimize the emotional and practical impacts on patients. The effects on providers, frequently not a central consideration, should be considered in ongoing debates regarding abortion regulation.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Society for Family Planning (SFPRF7- 15, Rebecca Mercier: PI). Mara Buchbinder’s efforts were supported by a grant from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (KL2TR001109). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Rebecca J. Mercier, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA.

Mara Buchbinder, Department of Social Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 341A MacNider Hall CB 7240 Chapel Hill, NC 27599.

Amy Bryant, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 4002 Old Clinic Building, CB 7570 Chapel Hill, NC 27514.

Laura Britton, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Carrington Hall, CB#7460 Chapel Hill, NC 27599.

References

- 1.Boonstra H, Nash E. A Surge of State Abortion Restrictions Puts Providers—and the Women They Serve—in the Crosshairs. Guttmacher Policy Review 2014. 2014 Oct;17(1):9–17. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson CT, Nash E. Misinformed Consent: The medical accuracy of state-developed abortion counseling materials. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2006;9(4):6–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gold RB, Nash E. State abortion counseling policies and the fundamental principles of informed consent. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2007;10(4):6–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinberger SE, Lawrence HC, Henley DE, Alden ER, Hoyt DB. Legislative interference with the patient-physician relationship. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(16):1557–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb1209858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Increasing Access to Abortion. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women: ACOG Committee Opinion. Nov, 2014. p. 613. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris LH, Martin L, Debbink M, Hassinger J. Physicians, abortion provision and the legitimacy paradox. Contraception. 2012;10(12):00797–4. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Russo JA, Schumacher KL, Creinin MD. Antiabortion violence in the United States. Contraception. 2012;86(5):562–6. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Freedman L, Landy U, Darney P, Steinauer J. Obstacles to the integration of abortion into obstetrics and gynecology practice. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;42(3):146–51. doi: 10.1363/4214610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medoff MH. The relationship between state abortion policies and abortion providers. Gender Issues. 2009;26:224–37. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris LH, Debbink M, Martin L, Hassinger J. Dynamics of stigma in abortion work: findings from a pilot study of the Providers Share Workshop. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(7):1062–70. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walker D, Myrick F. Grounded theory: an exploration of process and procedure. Qualitative health research. 2006 Apr;16(4):547–59. doi: 10.1177/1049732305285972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Annas GJ. Doctors, patients, and lawyers--two centuries of health law. N Engl J Med. 2012 Aug 2;367(5):445–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1108646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Runels S. Informed consent laws and the constitution: balancing state interests with a physician’s first amendment rights and a woman’s due process rights. The Journal of contemporary health law and policy. 2009 Fall;26(1):185–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tracy EE. Three is a crowd: the new doctor-patient-policymaker relationship. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1164–8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823188d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]