Distinct features of TCRβ repertoire present between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells could be used to evaluate the competency of the T cell immunity.

Keywords: Human, TCR diversity, supervised learning, RACE, RNAseq

Abstract

The TCR repertoire serves as a reservoir of TCRs for recognizing all potential pathogens. Two major types of T cells, CD4+ and CD8+, that use the same genetic elements and process to generate a functional TCR differ in their recognition of peptide bound to MHC class II and I, respectively. However, it is currently unclear to what extent the TCR repertoire of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is different. Here, we report a comparative analysis of the TCRβ repertoires of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by use of a 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends–PCR–sequencing method. We found that TCRβ richness of CD4+ T cells ranges from 1.2 to 9.8 × 104 and is approximately 5 times greater, on average, than that of CD8+ T cells in each study subject. Furthermore, there was little overlap in TCRβ sequences between CD4+ (0.3%) and CD8+ (1.3%) T cells. Further analysis showed that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells exhibited distinct preferences for certain amino acids in the CDR3, and this was confirmed further by a support vector machine classifier, suggesting that there are distinct and discernible differences between TCRβ CDR3 in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Finally, we identified 5–12% of the unique TCRβs that share an identical CDR3 with different variable genes. Together, our findings reveal the distinct features of the TCRβ repertoire between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and could potentially be used to evaluate the competency of T cell immunity.

Introduction

TCRs provide the specificity of the interaction between T cell and antigen–MHC complex [1]. Conventional TCRs consist of α and β chains that are generated by random recombination among numerous gene segments, creating TCRs of vastly different specificity, collectively called the TCR repertoire. TCR repertoire diversity can be characterized by the estimated number of unique TCRs in the total repertoire, a concept known as species richness. The enormous diversity of TCRs ensures successful recognition of all potential antigens and serves as a measure of immune-system competency [2]. The abundance of particular TCR clones reveals the immunologic history, immune status relative to pathogens, and environment of the host [3, 4]. As a result of its immense size and complexity, the precise characteristics of the TCR repertoire have not yet been fully determined.

TCRβ diversity has been theoretically estimated in the range of 1012–1015 [2, 5], whereas the experimentally estimated TCRβ diversity of an adult has ranged from 105 to 108 by traditional Sanger sequencing [6] or by next-generation sequencing [7–13]. However, it is unknown whether TCRβ diversity differs between the CD4+ and CD8+ T cells or whether the TCRβ diversity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is correlated. It is important to note that the term “species diversity” refers here to the estimated richness of the TCRβ repertoire. Although TCRs of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells recognize different peptides on class II and class I MHC complexes, respectively, it is unclear whether the CDR3 sequences of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are distinct or shared. A single TCR that can recognize both MHC class I and class II peptide complexes has been reported [14]. Such a TCR is considered as an exception rather than a norm.

T cell response to an antigen is often mounted by a heterogeneous group of T cells that possesses distinct TCRs [15, 16]. The subsequent fate of these responding T cells is influenced by the strength of TCR and MHC/peptide interaction, as well as environmental factors [17–19]. However, the structural basis for this heterogeneous TCR recognition to the same antigen has not been well characterized. A possible mechanism of the heterogeneous TCRs is that some TCRs share a common CDR3 but differ in other regions of TCR, such as CDR1 and CDR2, which are determined by the identity of the V gene segment. Such TCRs could have similar antigen specificity but varying levels of affinity with MHCs as a result of differing CDR1 and CDR2 sequences. Currently, it is unknown whether these types of TCRs exist and what proportion they occupy in the TCR repertoire.

Here, we used a RACE–PCR–next-generation sequencing method to measure directly the TCRβ richness and distribution in peripheral blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of 8 adults. We provided the estimated richness of TCRβ of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of these healthy adults, as well as the correlation between CD4+ and CD8+ estimated richness in any given individual. Furthermore, we demonstrated that distinct compositional differences separate TCRβ CDR3 of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, and these differences enable a supervised learning classifier to assign accurately a given TCRβ CDR3 to CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Finally, we showed that 6–10% of TCRβ shared identical CDR3 but different V genes, providing a structural basis for heterogeneous T cell response to a given antigen. These findings reveal the unique features of TCRβ in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, which may serve a basis for estimating the functional competency of T cells in an individual, as well as a guide for potential clinical intervention.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study subjects

Eight healthy blood donors, aged from 24 to 78, were selected for this study under an Institutional Review Board-approved protocol. Peripheral blood was obtained from these adults from National Institute on Aging Clinical Research Branch, National Institutes of Health (Baltimore, MD, USA), during their visit and processed for T cell isolation.

Isolation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

The procedure for isolation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was described previously [20]. In brief, PBMCs were isolated from blood and were used for isolating CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by use of the Dynal Positive Selection Kit (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA). The purities of isolated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were >96% in flow cytometric analysis.

TCRβ library construction

Total RNA was extracted from the cells by use of Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit (Valencia, CA, USA). One-third of isolated RNA, roughly 3–10 µg, was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis with TRBC-RT primer by use of SuperScript III (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific), according to the manufacturer's protocol. After purification of synthesized cDNA by use of a PCR Purification Kit (QIAquick; Qiagen), poly(A) tails were added at the 5′ end by use of TdT, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Fifteen cycles of PCR (PCR-1) amplification were carried out by use of 10 μl purified poly(A)-tailed cDNA with a RACE Classic-UF primer and a nested TRBC primer (Supplemental Table 1) with 5 units of DNA polymerase (Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity; Life Technologies, Thermo Fisher Scientific) under the conditions of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C, and 90 s at 68°C, plus a final extension for 10 min at 68°C. The amplified TCRβ products were purified with the PCR Purification Kit again.

Preparation of TCRβ libraries for Illumina sequencing

The adaptor used by the Genome Analyzer II (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) was added to the ends of TCRβ products by use of 2 sequential rounds of PCR. In the 1st round PCR (PCR-2), 10 μl of the purified TCRβ libraries was amplified with UF primer plus TRBJ_AAA and TRBJ_GAA primers (final 0.05 μM each) under 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 50°C, and 90 s at 72°C for 23 cycles, plus a final extension for 10 min at 72°C. PCR products, ranging from 430 to 780 bp, were purified from a 1.5% agarose gel with a Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). In the 2nd round PCR (PCR-3), the purified, previous round PCR products were amplified again with A-UF primer and A-TRBJ primers (final 0.1 μM each), which contain complete adaptor sequences under 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 65°C, and 90 s at 72°C for 20 cycles, plus a final extension for 10 min at 72°C. Again, the amplified PCR products ranging from 480 to 830 bp were purified the same as the 1st round.

Illumina sequencing

Purified 2nd round TCRβ DNA (2.5–3.5 pM) by the Agilent bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used for clustering. The sequencing reaction was carried out with TRBJ_AAA and TRBJ_GAA primers on a Genome Analyzer II with an SBS Sequencing Kit (v3–5; Illumina) for a 78 bp run, according to the manufacturer's protocol. A genomic DNA library with nearly the same percentage of A, T, C, and G bases was used with the Illumina Genomic Sequencing primer (v2) as a control in each flow cell to facilitate the auto-base calling during the run. The average sequence reads per sample were ∼10 million for CD4+, CD8+, and total T cells. Repeat sequencing of the same library for 16 samples showed that the overlapping of total TCRβs was 97.1%.

Sequencing data analysis

Raw DNA sequences were first analyzed to identify V and J genes by use of an edited version of the Decombinator [21]. Afterwards, these sequences were translated, and the CDR3 was identified based on the IMGT definitions. To ensure high-quality data, we applied a cutoff of the Phred QS of 30 to the tag-matching regions for V gene identity and for the region of the entire CDR3. We also analyzed those single-read distinct TCRβ sequences that had only 1 aa difference from other distinct TCRβ sequences with multiple reads from the same person. If the QS of the nucleotide(s) that is responsible for the amino acid change was <35, then we removed the single-read distinct TCRβ sequence and counted it as the other multiple-read distinct TCRβ sequences. With the use of these approaches, the occupancy of the single-read distinct TCRβ sequences was reduced from ∼80% to ∼36% (n = 30).

Validation of the TCRβ library preparation and sequencing

We designed specific PCR primers for 37 functional Vβ genes and 1 common primer at the constant region and used real-time quantitative PCR to compare the Vβ use in the amplified TCRβ library and its cDNA (Supplemental Table 2). The comparative threshold values of each V gene from the TCRβ library and cDNA were compared. The correlation between the TCRβ library and cDNA was significant (Supplemental Fig. 1A). We completed 2 separate rounds of sequencing for 11 TCRβ libraries, and we subsequently compared the overlap of TCRβ sequences between the 2 sequencing reactions. The distinct TCRβ sequences were shared at 58%, whereas the total TCRβ sequence reads were overlapped at 99.3% (Supplemental Fig. 1B).

Estimation of TCRβ diversity and calculation of TCRβ distribution and sharing

The estimated richness of the TCRβ repertoire of each sample was computed by use of the Chao1bc, a nonparametric estimator of species richness that presumes nondestructive sampling [22, 23]. The distribution of TCRβ was carried out by recording the reads of each distinct TCRβ sequence in a library and then calculating the percentage of each number of TCRβ sequences in the distinct TCRβs. We deposited all TCRβ sequences from all subjects in a database, which allowed comparisons among shared CD4+, CD8+, or total T cell TCRβ sequences in different subjects. The frequencies of shared sequences in each sample were calculated with the unique CDR3 pool.

Statistical analysis

Identification of positional differences in amino acid composition (see Fig. 2) between CD4+ and CD8+ cells was assessed by generalized linear-mixed effect models by use of a Poisson distribution, including a random effect at the observation level to address dispersion. For those amino acid positions where significant differences in amino acid distribution were identified, post hoc comparisons of amino acid compositional differences between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were performed by use of a Fisher’s exact test with multiple comparison adjustment by use of FDR. Two-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, used in testing differences between CD4 and CD8 V and J gene allele distributions, was done by use of Python’s SciPy Library [24].

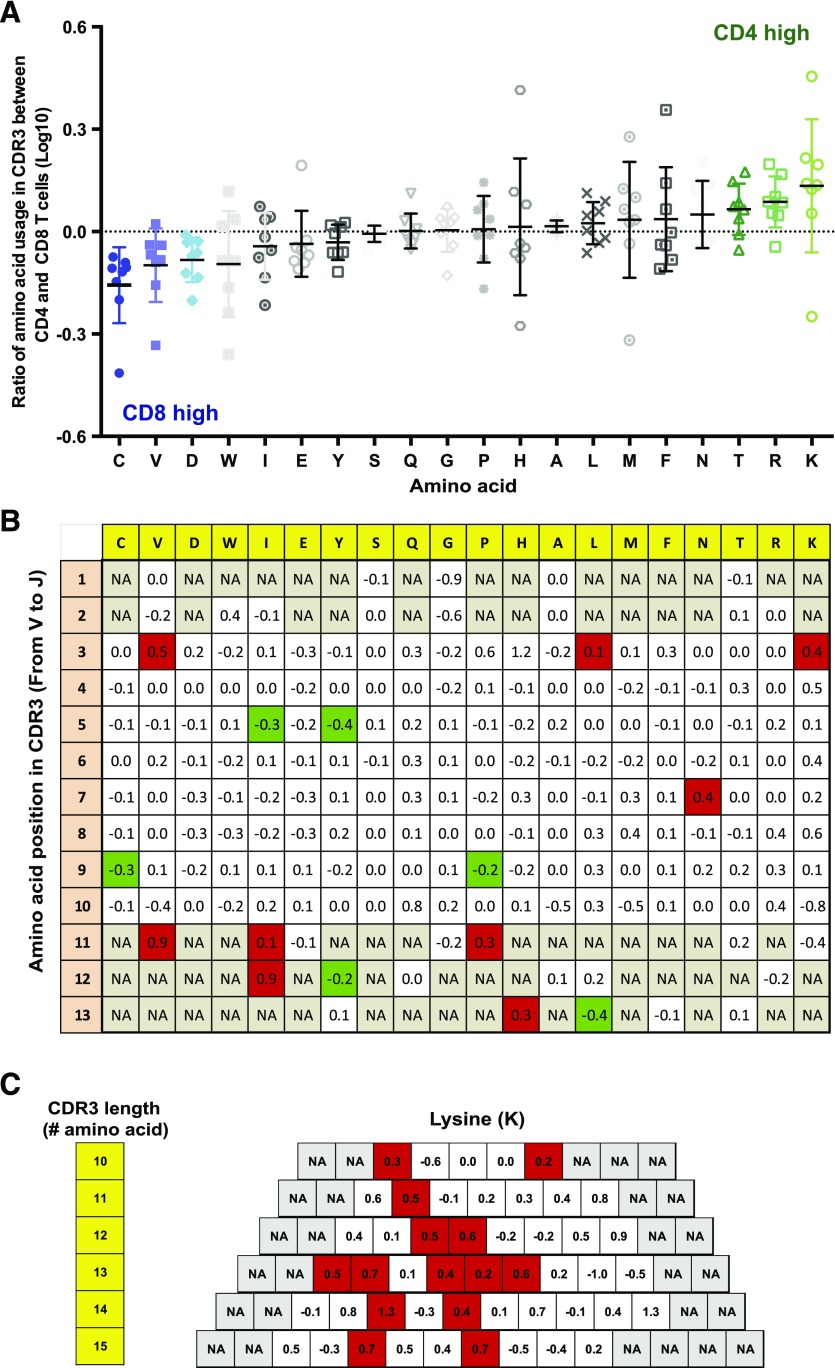

Figure 2. Preferential amino acid use in CDR3 of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

(A) Difference of amino acid use in CDR3 of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The proportion of each amino acid in CDR3 of all distinct TCRβs in CD4+ (242,578) and CD8+ (59,545) T cells was calculated as percentage of each amino acid within total amino acids for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The ratio of each amino acid use percentage between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was presented in log10 value. C, Cysteine; V, valine; D, aspartic acid; W, tryptophan; I, isoleucine; E, glutamic acid; Y, tyrosine; S, serine; Q, glutamine; G, glycine; P, proline; H, histidine; A, alanine; L, leucine; M, methionine; F, phenylalanine; N, asparagine; T, threonine; R, arginine; K, lysine. (B) Amino acid use in each position of CDR3 in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. The length of CDR3 of 13 aa was used for analysis, and amino acid in each position was calculated as a ratio between CD4+ and CD8+ TCRβs. Data derived from CDR3 that include 168,110 TCRβs from CD4+ and 18,999 distinct TCRβs from CD8+ T cells were presented (in log10). Green indicates significantly CD8-favored positions, and red indicates significantly CD4-favored positions. (C) Preferential locations of lysine in different lengths of CDR3 (10–15 aa) in CD4+ T cells. The average ratios of lysine use in different lengths of CDR3 (10–15 aa) between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in 8 subjects are presented (in log10). Multiple 2-sample independent Student’s t test was used, and FDR <0.10 is considered as significant, marked in red. NA, No value.

Supervised learning

All CDR3 amino acid sequences were converted to numerical arrays of Atchley factors [25] for each CDR3 length, from 11 to 15, to obtain numerical descriptors of amino acid sequences. Further analysis was performed with custom-written Python scripts by use of Python’s sklearn SVM library [26]. In short, a training set for supervised SVM learning was constructed with a mixture of CD4+ and CD8+ Atchley factor-vectorized CDR3 amino acid sequences based on 75% of our data, and the SVM classifier was cross-validated with a testing subset of our CDR3 sequences from the other 25% of our data. A minor number (<1% of both unique pools) of CDR3s that were present in CD4+ and CD8+ repertoires were removed to better segregate the CD4+ and CD8+ pools. One hundred rounds of bootstrap were performed to generate a confidence interval. This methodology is derived from the methods first used by Thomas et al. [27].

RESULTS

TCRβ repertoire richness of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

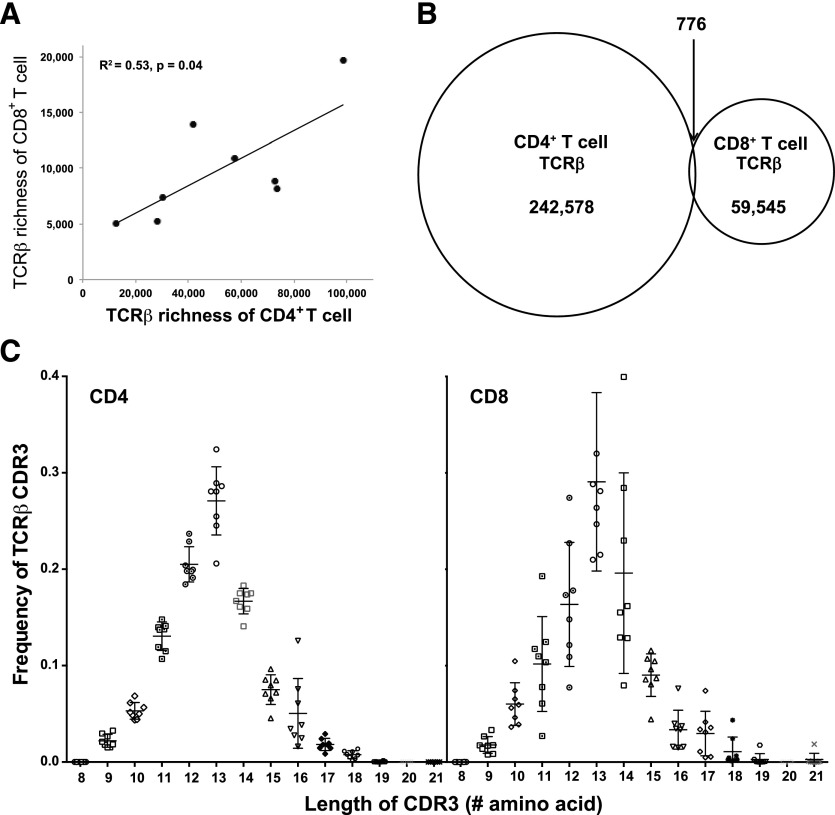

To determine the TCRβ species richness, we combined a RACE–PCR–sequencing approach with robust DNA error-checking and removal method to analyze the TCRβ repertoire of 8 healthy adults (CS1–CS8) in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (see Materials and Methods for details). The same number of cells (10 million CD4+ and CD8+ T cells) was used in all subjects. A number of different metrics have been used to measure TCR repertoire diversity. Here, we chose to measure the number of unique TCRβ species without regards to their abundance, a concept known as species richness, by use of Chao1bc, a statistically robust, nonparametric estimator of species richness [22, 23]. Species-richness estimates ranged from 1.2 to 9.8 × 104 for CD4+ T cells and from 0.5 to 1.9 × 104 for CD8+ T cells (Table 1). We used the diverse Chao1bc, as we wished to infer the total number of species (distinct TCRβs) that occurs in the total population from which we are sampling. The Chao1bc index estimates repertoire species richness by estimating the number of undetected species from the abundance data of a particular sampling and adding it to the observed species richness [22, 23]. The estimated richness of TCRβ of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was highly individualized. Interestingly, TCRβ richness of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was positively correlated for a given individual (R2 = 0.52; P = 0.04; Fig. 1A), the TCRβ richness in CD4+ T cells was greater than in CD8+ T cells for each individual, and the average ratio between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was 5.3 ± 2.3 (average ± sd; Table 1). The abundance of these TCRβs was characterized further in 3 groups based on the reads detected by sequencing per distinct TCRβ: low (1–10 reads), medium (11–100 reads), and high (>100 reads), as the percentages of total distinct TCRβ sequences (Table 1). CD8+ T cells contained more-abundant TCRβs (>100 copies; 9.1%) than did CD4+ T cells (5.0%; Table 1).

TABLE 1.

TCRβ richness and distribution in CD4+ and CD8+ T cellsa

| Donor | Age | CD4+ | CD8+ | Ratio of CD4/CD8 richness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Richness | Abundance distribution (%)b | Richness | Abundance distribution (%) | |||||||

| 1–10 | 11–100 | >100 | 1–10 | 11–100 | >100 | |||||

| CS1 | 21 | 41,901 | 75.0 | 19.2 | 5.8 | 13,952 | 69.2 | 22.7 | 8.1 | 3.0 |

| CS2 | 23 | 30,355 | 73.0 | 21.0 | 6.1 | 7,432 | 72.6 | 16.8 | 10.6 | 4.1 |

| CS3 | 26 | 72,700 | 80.1 | 15.0 | 4.9 | 8,898 | 69.4 | 21.3 | 9.3 | 8.2 |

| CS4 | 41 | 98,512 | 78.5 | 16.2 | 5.3 | 19,640 | 74.2 | 17.6 | 8.2 | 5.0 |

| CS5 | 53 | 57,466 | 78.9 | 17.7 | 3.4 | 10,940 | 73.0 | 20.5 | 6.5 | 5.3 |

| CS6 | 54 | 12,837 | 78.8 | 17.7 | 3.5 | 5103 | 72.9 | 18.1 | 9.0 | 2.5 |

| CS7 | 68 | 73,580 | 80.8 | 14.6 | 4.6 | 8148 | 74.8 | 15.8 | 9.3 | 9.0 |

| CS8 | 78 | 28,316 | 74.4 | 19.8 | 5.8 | 5287 | 68.0 | 20.1 | 11.9 | 5.4 |

| Average | 51,958 | 77.4 | 17.7 | 4.9 | 9925 | 71.8 | 19.1 | 9.1 | 5.3 | |

| SD | 28,667 | 2.9 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 4882 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 2.3 | |

The estimated species richness of each sample were calculated by the Chao1bc.

TCRβ sequences of 1 × 107 CD4+ or CD8+ T cells isolated from PBMC of 8 donors (CS1–CS8) were determined by Illumina Genome Analyzer II.

The percentage was calculated based on the number (read) per TCRβ with each group over the total distinct sequences.

Figure 1. Features of the TCRβ repertoire in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

(A) Correlation of TCRβ species richness between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in each study subject. TCRβs in 1 × 107 CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from 8 donors (CS1–CS8) were determined by Illumina Genome Analyzer II., and the diversity size was calculated by use of the Chao1bc method [22, 23]. The TCRβ diversities in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in a given donor were positively correlated. The R2 of the linear trend line was 0.52, and P = 0.04. (B) TCRβ sequences are distinct between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Among the total TCRβ sequences identified in 8 study subjects, CD4+ T cells have 242,578 distinct TCRβs, and CD8+ T cells have 59,545 distinct TCRβs; only 776 distinct TCRβs were found in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, accounting for 0.3 and 1.3% of the distinct TCRβs in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively. (C) TCRβ CDR3 length distribution between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. CDR3 length was counted based on the IMGT definition, and the percentage of each length of CDR3 was further calculated in the distinct TCRβ of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of each subject. The means and sd are presented for each length of CDR3.

Distinct TCRβ CDR3 sequences between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

Next, we investigated whether the TCRβ sequences are distinct between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Among the 242,578 distinct TCRβs from CD4+ and 59,545 distinct TCRβs from CD8+ T cells of 8 individuals combined, only 776 distinct TCRβs were found in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, accounting for 0.3 and 1.3% of the distinct TCRβs in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively (Fig. 1B). The low overlap of TCRβ sequences between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was not a result of the different lengths of CDR3s, as both displayed a similar range (9–24 aa) and distribution (Fig. 1C), nor related to biased V and J gene use (Supplemental Table 3). These results showed that overall CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have distinct TCRβs and that a very small number of TCRβs may be capable of reacting with MHC class I- and class II-bound peptide ligands when they pair with a suitable TCRα chain [14].

Preferential amino acid use of TCRβ CDR3s in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

To examine further the difference of the TCRβ sequence between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, we analyzed the amino acid use of CDR3 between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. CDR3 sequences from CD4+ T cells contained significantly higher percentages of lysine, arginine, and threonine and lower percentages of aspartic acid, cysteine, and valine than CDR3 sequences from CD8+ T cells in these 8 subjects (Fig. 2A). To rule out the potential bias as a result of the size of distinct TCRβs between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in these observed differences, we randomly selected half of the TCRβs from CD4+ or CD8+ T cells and compared the selected half with the remaining half of TCRβs. No significant differences were observed among CD4+ T cells or among CD8+ T cells. It is intriguing that TCRβ CDR3 of CD4+ T cells was more often associated with positively charged (lysine and arginine) amino acids, whereas TCRβ CDR3 of CD8+ T cells was more often associated with negatively charged (aspartic acid) amino acids.

To determine if the preferential use of certain amino acids has a locational dependence in the CDR3 of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, we examined those TCRβs with the same CDR3 length between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. CDR3s, consisting of 13 aa in length, which was the most abundant length, accounting for 27 and 29% distinct CDR3 in the TCR repertoire for CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively, were used. We found that CD4+ T cells preferentially used lysine located in position 3, valine at positions 3 and 11, and asparagine in position 7 relative to CD8+ T cells and that CD8+ T cells preferably used cysteine and proline in position 9 and isoluecine and tyrosine in position 5 relative to CD4+ T cells (Fig. 2B). In addition, we found some amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, proline, and tyrosine) that did not show a significant difference in overall CDR3 comparisons between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells but exhibited significant difference at certain defined positions of CDR3 between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2B). To extend the analysis of preferential use of amino acids to different lengths of CDR3, we analyzed CDR3 from 10 to 15 aa in length. Collectively, TCRβs of CDR3 from 10 to 15 aa accounted for 90% of all distinct TCRβs. Preferential use of lysine was located in certain positions irrespective of the length of CDR3 (Fig. 2C). Together, these findings demonstrated that specific amino acids are preferred at particular positions in CDR3 of TCRβ in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

Systemic classification of CDR3s by T cell compartment by use of sequence features

To determine further if there are characteristics to distinguish CDR3s between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, we developed a machine-learning approach inspired by the methodology used by Thomas et al. [27]. We first converted the amino acid sequences to numerical arrays made of Atchley factors, which are 5 unique numbers encoding the most important chemical and physical properties regarding each amino acid [25]. These numerical arrays were then supplied into a common, supervised learning model, known as a SVM, which when properly trained, uses relevant information to classify new inputs into binary categories (i.e., whether a new CDR3 sequence belongs to the CD4+ or CD8+ compartment). If a binary classifier can repeatedly assign a new random input with high accuracy into its correct category, then this suggests that there are certain features in the dataset that enable the model to discern between the 2 categories. Here, we trained the SVM with numerical vectors of 75% of our unique CDR3 sequences as the training set and 25% of data as a cross-validation set. We were able to identify the origin of a significant percentage of CDR3 to CD4+ or CD8+ T cells with a reasonable degree of accuracy (Table 2), suggesting that CD4+ and CD8+ TCRβ CDR3 sequences exhibit systemic differences at the amino acid level that can be reasonably classified. This implies that there may be higher-level patterns that are able to differentiate uniquely between CD4+ and CD8+ TCRβ CDR3s. To discount any interference from preferential V or J gene use between CD4+ and CD8+ CDR3s, we conducted a 2-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test on the distributions of both V and J gene alleles. The resulting values suggest that there are no significant differences between the 2 distributions (Supplemental Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Predicting CDR3 origin by supervised learninga

| CDR3 amino acids | CD4+ |

CD8+ |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy ± sdb | Accuracy ± sd | |

| 10 | 0.90 ± 0.01 | 0.82 ± 0.01 |

| 11 | 0.81 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 |

| 12 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 |

| 13 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.85 ± 0.01 |

| 14 | 0.92 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.01 |

| 15 | 0.96 ± 0.01 | 0.97 ± 0.00 |

| Average | 0.88 ± 0.01 | 0.88 ± 0.01 |

CDR3 from CD4+ or CD8+ T cells is predicted by the SVM classifier.

Accuracy is presented as proportion ± sd.

Occupancy of different TCRβs with shared identical CDR3 but different V genes in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells

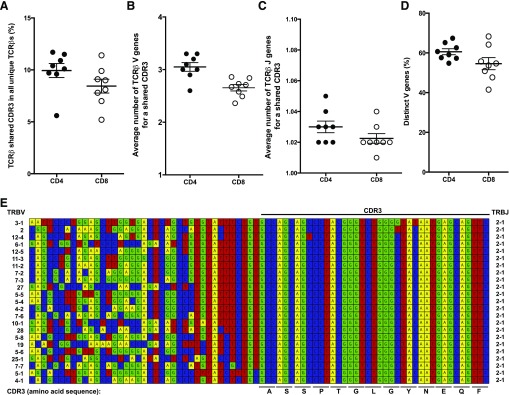

During sequence comparison, we identified a number of TCRβs that had identical CDR3 amino acid sequences but were associated with different V genes. These TCRβs, if paired with similar TCRαs, could recognize similar or the same peptide/MHC complex with different affinity, which could serve as the basis for the heterogeneous T cell response to a defined antigen. Individually, TCRβs that had identical CDR3 but different V genes accounted for ∼9.9% (5.6–11.5%) and 8.4% (5.2–11.4%) of all distinct TCRβs in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3A). We then did the same analysis by use of a published data set [7] and found that TCRβs that had identical CDR3 but different V genes accounted for 4.6% of all distinct TCRβs. In our data, the average number of V genes per identical CDR3 was 3.0 for CD4+ T cells compared with 2.7 for CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3B), and J gene was 1.03 for CD4+ T cells compared with 1.02 for CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3C). To determine further how similar the different V gene sequences are in these TCRβs, we considered submembers within a gene family as similar and different V gene families as distinct and found that distinct V genes in these TCRβs accounted for an average of 61% and 54% in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively (Fig. 3D). The greater use of V genes in CD4+ relative to CD8+ T cells and the higher percentage of these similar TCRβs in CD4+ T cells provide a partial explanation of the larger TCRβ diversity of CD4+ T cells relative to CD8+ T cell diversity. The use of different V genes for an identical CDR3 ranged broadly from 2 to 23. The presence of as many as 23 V genes sharing the same CDR3 sequence in CD4+ T cells of 1 subject (CS3) reveals an aspect of TCRβ diversity that is based on the differences in the CDR1 and CDR2 sequences rather than the traditional CDR3 signature (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3. Characters of TCRβs with same CDR3 but different V genes.

(A) Frequency of TCRβs with the same CDR3 but different V genes in distinct TCRβs of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells of all 8 subjects. (B and C) Average number of V and J genes of TCRβs with the same CDR3 in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Each symbol indicates 1 of 8 subjects. (D) Percent of distinct V genes (total of 23 distinct V gene family) in distinct TCRβs sharing an identical CDR3 amino acid sequence in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Each symbol indicates 1 of all 8 subjects. Means and sem were presented. (E) A representative alignment of TCRβs with the same CDR3 but 23 different V genes from 13 different V gene families. These sequences were from CD4+ T cells (combined data from 1 × 107 and 1 × 108 cells) of subject CS3. CDR3 definition is based on IMGT, and amino acids in the CDR3 are indicated. V [TCRβ variable (TRBV)] and J gene uses (TRBJ) are indicated in left and right side of the alignment, respectively.

DISCUSSION

To accurately assess the size of the human TCR repertoire has been challenging. The estimation of human TCRβ diversity or richness presented here is based on use of high-quality sequences and application of high-QS cutoffs for those nucleotide(s) that are responsible for amino acid changes. Our data show that TCRβ richness of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells is highly individualized but is comparable between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells for a given person, suggesting that the TCRβ repertoire of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in an individual may be shaped in parallel by both genetic and environmental factors.

The comparison of the estimated richness of TCRβ of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from the same adults revealed that the TCRβ-estimated richness is ∼5 times greater in CD4+ than in CD8+ T cells. This difference is not a result of an overabundance of CD4+ T cells in blood, as the same number of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells was used in the analysis. Peptides bound with MHC class I are mostly 9 aa in length (ranging from 8 to 15 aa) [28], whereas peptides bound to MHC class II are more flexible (ranging from 11 to 30 aa) in length [29]. It is unclear whether CD4+ TCRβs recognize greater numbers of antigenic epitopes than do CD8+ T cells whether or more distinct TCRs of CD4+ T cells recognize the same antigenic epitope than do CD8+ T cells. Although the stability of TCRβ richness in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells over time is not fully clear, 2 recent reports show that TCRβ richness was smaller in old subjects than in young subjects [12, 13]. A longitudinal assessment of TCRβ diversity of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells will be necessary to clarify this issue further.

An interesting finding of this study is that the TCRβ CDR3s are distinct between CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Amino acid composition analysis of CDR3 revealed the preferential use of certain positively and negatively charged amino acids in CDR3s of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, respectively, suggesting that CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have structurally distinct TCRβ CDR3s. This distinction is not a result of a preferential use of V or J genes in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Supplemental Table 3).This preferential use of particular amino acids prompted us to explore whether a supervised learning classifier is able to capture the complex differences in amino acid use. Here, a SVM was able to assign accurately a random CDR3 to the CD4+ or CD8+ T cells with high accuracy when tested with a random subset of our data, suggesting that there are certain distinct features of the CDR3 in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Clearly, further testing with more subjects and with a larger number of TCRβ sequences, along with a parallel analysis of peptide/MHC complexes and CD4+/CD8+ TCRs, will be necessary to unravel the complexity and distinct structural features of the interaction between T cells and peptide/MHC. These experiments, along with increased abundance of TCRα sequences [30], will enable computational models to be constructed that will clarify the differences between CD4+ and CD8+ TCRs. Heterogeneity of a T cell response to a defined antigen is increasingly recognized in the T cell response to viral antigens and to cancer antigens [15]. The sensitivity and recognition efficiency of responding heterogeneous T cells could affect the overall efficacy of the response. The estimated number of T cells for a given response ranges from a few to a few hundred different naive T cells [16]. However, the structural basis of the TCR in these heterogeneous T cells has not been analyzed extensively. Our finding of different TCRβs that share identical CDR3 provides a potential structural basis for these heterogeneous T cells when they pair with an identical or structurally similar TCRα. They are quite abundant (5–12%) in the distinct TCRβs and consistently found in different subjects, suggesting that these T cells may play an important role in T cell function and repertoire maintenance. How these types of TCRβs are generated is currently unknown. Based on J gene use (Fig. 3C), the majority of them may arise from the immature thymocytes of a common precursor cell after D–J rearrangement, and a minor fraction of them is generated by completely independent recombination events in different T cells by coincidence. Direct sequencing of TCRs of those T cells with a defined antigen specificity will provide further evidence of the contribution of this type of TCRβ in the pool of heterogeneous T cells. Furthermore, a rigorous statistical treatment that uses maximum likelihood models for specific TCRβ clonotype generation probabilities used by Murugan et al. [31] may yield additional insights as to the frequencies of different TCRβs that share identical CDR3.

It is clear that further studies with greater numbers of subjects, improved methodology [32], and parallel analysis of both TCRα and TCRβ repertoires will be needed to measure more accurately the human TCR repertoire. Detailed information of the TCR repertoire of all T cells, including pathogen-specific T cells, in an individual is critically important for a better understanding of T cell responses before, during, and after infection or vaccination [33, 34]. The monitoring of TCR repertoire changes during autologous HSCT reveals that diversity of TCR after HSCT serves as an indicator of the treatment [35]. The TCR diversity change during CTLA-4 blockade treatment shows that a well-maintained TCR diversity is associated with improved overall survival, whereas patients who have reduced TCR diversity have short overall survival [36]. Although a complete catalog of human CD4+ and CD8+ TCR sequences and their binding specificity is still a long way away, such information will serve as a foundation for immune-based diagnosis, treatment, and vaccination and potentially fulfill the great promise of personalized medicine.

AUTHORSHIP

N.-p.W., H.M.L., and T.H. conceived of the project and designed experiments. H.M.L. and T.H. did experiments with help from G.C. and W.H.W. Y.Z. and A.S. did data analysis with assistance from S.D., E.J.M., A.S., J.D.M., K.G.B., and M.Z. N.-p.W., T.H., A.S., and H.M.L. wrote the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the U.S. National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging (NIA). The authors thank Ranjan Sen for critically reviewing the manuscript, Dr. Luigi Ferrucci for his support in studying the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging participants, and NIA Clinical Core Lab for collecting blood samples.

Glossary

- CDR3

complementarity-determining region 3

- Chao1bc

Chao 1 bias-corrected estimator

- FDR

false discovery rate

- HSCT

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- IMGT

immunogenetics database

- J

joining

- QS

quality score

- RACE

rapid amplification of cDNA ends

- SVM

support vector machine

- TRBC

TCRβ constant

- TRBJ

TCRβ joining

- V

variable

Footnotes

The online version of this paper, found at www.jleukbio.org, includes supplemental information.

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davis M. M., Bjorkman P. J. (1988) T-Cell antigen receptor genes and T-cell recognition. Nature 334, 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikolich-Zugich J., Slifka M. K., Messaoudi I. (2004) The many important facets of T-cell repertoire diversity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4, 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turner S. J., Diaz G., Cross R., Doherty P. C. (2003) Analysis of clonotype distribution and persistence for an influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell response. Immunity 18, 549–559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naumova E. N., Gorski J., Naumov Y. N. (2009) Two compensatory pathways maintain long-term stability and diversity in CD8 T cell memory repertoires. J. Immunol. 183, 2851–2858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turner S. J., Doherty P. C., McCluskey J., Rossjohn J. (2006) Structural determinants of T-cell receptor bias in immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6, 883–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arstila T. P., Casrouge A., Baron V., Even J., Kanellopoulos J., Kourilsky P. (1999) A direct estimate of the human alphabeta T cell receptor diversity. Science 286, 958–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freeman J. D., Warren R. L., Webb J. R., Nelson B. H., Holt R. A. (2009) Profiling the T-cell receptor beta-chain repertoire by massively parallel sequencing. Genome Res. 19, 1817–1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robins H. S., Campregher P. V., Srivastava S. K., Wacher A., Turtle C. J., Kahsai O., Riddell S. R., Warren E. H., Carlson C. S. (2009) Comprehensive assessment of T-cell receptor beta-chain diversity in alphabeta T cells. Blood 114, 4099–4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robins H. S., Srivastava S. K., Campregher P. V., Turtle C. J., Andriesen J., Riddell S. R., Carlson C. S., Warren E. H. (2010) Overlap and effective size of the human CD8+ T cell receptor repertoire. Sci. Transl. Med. 2, 47ra64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang C., Sanders C. M., Yang Q., Schroeder H. W. Jr., Wang E., Babrzadeh F., Gharizadeh B., Myers R. M., Hudson J. R. Jr., Davis R. W., Han J. (2010) High throughput sequencing reveals a complex pattern of dynamic interrelationships among human T cell subsets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1518–1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zvyagin I. V., Pogorelyy M. V., Ivanova M. E., Komech E. A., Shugay M., Bolotin D. A., Shelenkov A. A., Kurnosov A. A., Staroverov D. B., Chudakov D. M., Lebedev Y. B., Mamedov I. Z. (2014) Distinctive properties of identical twins’ TCR repertoires revealed by high-throughput sequencing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 5980–5985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Britanova O. V., Putintseva E. V., Shugay M., Merzlyak E. M., Turchaninova M. A., Staroverov D. B., Bolotin D. A., Lukyanov S., Bogdanova E. A., Mamedov I. Z., Lebedev Y. B., Chudakov D. M. (2014) Age-related decrease in TCR repertoire diversity measured with deep and normalized sequence profiling. J. Immunol. 192, 2689–2698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi Q., Liu Y., Cheng Y., Glanville J., Zhang D., Lee J. Y., Olshen R. A., Weyand C. M., Boyd S. D., Goronzy J. J. (2014) Diversity and clonal selection in the human T-cell repertoire. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 13139–13144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yin L., Huseby E., Scott-Browne J., Rubtsova K., Pinilla C., Crawford F., Marrack P., Dai S., Kappler J. W. (2011) A single T cell receptor bound to major histocompatibility complex class I and class II glycoproteins reveals switchable TCR conformers. Immunity 35, 23–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stuge T. B., Holmes S. P., Saharan S., Tuettenberg A., Roederer M., Weber J. S., Lee P. P. (2004) Diversity and recognition efficiency of T cell responses to cancer. PLoS Med. 1, e28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chu H. H., Moon J. J., Takada K., Pepper M., Molitor J. A., Schacker T. W., Hogquist K. A., Jameson S. C., Jenkins M. K. (2009) Positive selection optimizes the number and function of MHCII-restricted CD4+ T cell clones in the naive polyclonal repertoire. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 11241–11245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tao X., Constant S., Jorritsma P., Bottomly K. (1997) Strength of TCR signal determines the costimulatory requirements for Th1 and Th2 CD4+ T cell differentiation. J. Immunol. 159, 5956–5963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Busch D. H., Pamer E. G. (1999) T cell affinity maturation by selective expansion during infection. J. Exp. Med. 189, 701–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denton A. E., Wesselingh R., Gras S., Guillonneau C., Olson M. R., Mintern J. D., Zeng W., Jackson D. C., Rossjohn J., Hodgkin P. D., Doherty P. C., Turner S. J. (2011) Affinity thresholds for naive CD8+ CTL activation by peptides and engineered influenza A viruses. J. Immunol. 187, 5733–5744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Son N. H., Murray S., Yanovski J., Hodes R. J., Weng N. (2000) Lineage-specific telomere shortening and unaltered capacity for telomerase expression in human T and B lymphocytes with age. J. Immunol. 165, 1191–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thomas N., Heather J., Ndifon W., Shawe-Taylor J., Chain B. (2013) Decombinator: a tool for fast, efficient gene assignment in T-cell receptor sequences using a finite state machine. Bioinformatics 29, 542–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chao A. (1984) Nonparametric estimation of the number of classes in a population. Scand. J. Statist. 11, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gotelli N. J., Colwell R. K. ( 2011) Estimating species richness. In Frontiers in Measuring Biodiversity (Magurran A. F., McGill B. J., eds.), Oxford University Press, New York, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Der Walt S., Colbert S. C., Varoquaux G. (2011) The NumPy array: a structure for efficient numerical computation. Comput. Sci. Eng. 13, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atchley W. R., Zhao J., Fernandes A. D., Drüke T. (2005) Solving the protein sequence metric problem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 6395–6400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pedregosa F., Varoquaux G., Gramfort A., Michel V., Thirion B., Grisel O., Blondel M., Prettenhofer P., Weiss R., Dubourg V., Vanderplas, J., Passos, A., Cournapeau, D., Brucher, M., Perrot, M., Duchesnay, É. (2011) Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas N., Best K., Cinelli M., Reich-Zeliger S., Gal H., Shifrut E., Madi A., Friedman N., Shawe-Taylor J., Chain B. (2014) Tracking global changes induced in the CD4 T-cell receptor repertoire by immunization with a complex antigen using short stretches of CDR3 protein sequence. Bioinformatics 30, 3181–3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schumacher T. N., De Bruijn M. L., Vernie L. N., Kast W. M., Melief C. J., Neefjes J. J., Ploegh H. L. (1991) Peptide selection by MHC class I molecules. Nature 350, 703–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rammensee H. G., Friede T., Stevanoviíc S. (1995) MHC ligands and peptide motifs: first listing. Immunogenetics 41, 178–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marrack P., Scott-Browne J. P., Dai S., Gapin L., Kappler J. W. (2008) Evolutionarily conserved amino acids that control TCR-MHC interaction. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 26, 171–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Murugan A., Mora T., Walczak A. M., Callan C. G. Jr. (2012) Statistical inference of the generation probability of T-cell receptors from sequence repertoires. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 16161–16166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shugay M., Britanova O. V., Merzlyak E. M., Turchaninova M. A., Mamedov I. Z., Tuganbaev T. R., Bolotin D. A., Staroverov D. B., Putintseva E. V., Plevova K., Linnemann C., Shagin D., Pospisilova S., Lukyanov S., Schumacher T. N., Chudakov D. M. (2014) Towards error-free profiling of immune repertoires. Nat. Methods 11, 653–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.La Gruta N. L., Thomas P. G. (2013) Interrogating the relationship between naïve and immune antiviral T cell repertoires. Curr. Opin. Virol. 3, 447–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Woodsworth D. J., Castellarin M., Holt R. A. (2013) Sequence analysis of T-cell repertoires in health and disease. Genome Med. 5, 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muraro P. A., Robins H., Malhotra S., Howell M., Phippard D., Desmarais C., de Paula Alves Sousa A., Griffith L. M., Lim N., Nash R. A., Turka L. A. (2014) T cell repertoire following autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple sclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 1168–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cha E., Klinger M., Hou Y., Cummings C., Ribas A., Faham M., Fong L. (2014) Improved survival with T cell clonotype stability after anti-CTLA-4 treatment in cancer patients. Sci. Transl. Med. 6, 238ra70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.