Abstract

Smoking is a dominant risk factor for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and emphysema, but not every smoker develops emphysema. Immune responses in smokers vary. Some autoantibodies have been shown to contribute to the development of emphysema in smokers. β2-adrenergic receptors (β2-ARs) are important targets in COPD therapy. β2-adrenergic receptor autoantibodies (β2-AAbs), which may directly affect β2-ARs, were shown to be increased in rats with passive-smoking-induced emphysema in our current preliminary studies. Using cigarette-smoke exposure (CS-exposure) and active-immune (via injections of β2-AR second extracellular loop peptides) rat models, we found that CS-exposed rats showed higher serum β2-AAb levels than control rats before alveolar airspaces became enlarged. Active-immune rats showed increased serum β2-AAb levels, and exhibited alveolar airspace destruction. CS-exposed-active-immune treated rats showed more extensive alveolar airspace destruction than rats undergoing CS-exposure alone. In our current clinical studies, we showed that plasma β2-AAb levels were positively correlated with the RV/TLC (residual volume/total lung capacity) ratio (r = 0.455, p < 0.001) and RV%pred (residual volume/residual volume predicted percentage, r = 0.454, p < 0.001) in 50 smokers; smokers with higher plasma β2-AAb levels exhibited worse alveolar airspace destruction. We suggest that increased circulating β2-AAbs are associated with smoking-related emphysema.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, and tobacco smoking is the dominant risk factor for COPD. Emphysema is defined pathologically as an abnormal, permanent enlargement of the airspaces distal to the terminal bronchioles. In addition, there are still no effective ways to reverse the progress of emphysema. The Evaluation of COPD Longitudinally to Identify Predictive Surrogate End-points (ECLIPSE) cohort study used a cluster analysis to show that COPD patients with severe emphysema underwent a greater reduction in health status, a faster progression of emphysema, a higher exacerbation rate, and a greater deterioration of clinical symptoms1. However, only 15–20% of smokers develop COPD and not all COPD patients or smokers exhibit emphysema2. This indicates that individual susceptibility to smoke exposure varies among different people, and research on the underlying mechanism may contribute to developing individualized treatments.

Recent evidence suggests that autoimmunity plays a role in the pathogenesis of COPD and emphysema3,4. The damage-repair process in the development of COPD and emphysema may activate the immune system, resulting in autoantibody production5. Previous studies have demonstrated the existence of anti-elastin and anti-endothelial cell (EC) antibodies associated with emphysema, which can cause lung parenchyma destruction and alveolar airspace enlargement, and the levels of these autoantibodies vary among different people6,7. An autoantigen array analysis found that patients with emphysema produced higher antibody titres and were reactive to an increased number of antigens. Strikingly, the levels of autoantibody reactivity observed in cases of emphysema were increased, even over those detected in rheumatoid arthritis patients and were similar to those associated with lupus8.

β2-adrenergic receptors (β2-ARs) are important targets in the treatment of lung disease. β2-adrenergic receptors are widely distributed in lung cells, such as airway smooth muscle cells, epithelial cells, and inflammatory cells9,10,11. β2-adrenergic receptor agonists are involved in regulating airway smooth muscle tone12. Our previous studies also reported that β2-adrenergic receptors are involved in anti-inflammatory and anti-hypersecretory functions in vivo and in vitro13,14. Increasing evidence suggests that β-adrenergic receptor (β-AR) autoantibodies act as pathogenic drivers, and the extracellular domains of receptor proteins are targets for autoimmune recognition15. However, only a few studies have focused on β2-AR autoantibodies (β2-AAbs). One type of inhibitory β2-AAb against the third extracellular loop of the receptor has been reported to contribute to the adrenergic hyporesponsiveness observed in asthma patients16. Agonistic β2-AAbs against the second extracellular loop of the receptor have been reported in Chagas’ cardiomyopathy, open-angle glaucoma, and regional pain syndrome17. Agonistic β2-AAbs against the first extracellular loop of the receptor have been reported in association with Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia18 and may cause vascular damage. No studies have shown any evidence for a link between emphysema and β2-AAbs.

Long-term passive smoking is an effective way to induce emphysema in rats19. Our current preliminary studies showed that serum levels of β2-AAbs against the β2-AR second extracellular loop peptide (ECLII peptide), were increased in passive-smoking rats with emphysema relative to levels in control rats. Thus, we hypothesized that increased levels of β2-AAbs may be associated with an increase in the extent of emphysema. To test this hypothesis, we established a rat model of cigarette-smoke exposure (CS-exposure) and a rat active-immune model using β2-AR ECLII peptide injections, and we combined CS-exposure and immune activation in another group of rats to explore the changes in serum β2-AAb levels and the associated pathological and functional changes in the lungs. We also performed a clinical study in a group of smokers to further study this relationship. The aim of this study was to investigate whether β2-AAbs are involved in emphysema.

Results

Measurements for the CS-exposure rat model

CS-exposed rats showed increased serum β2-AAb levels before alveolar airspaces became enlarged

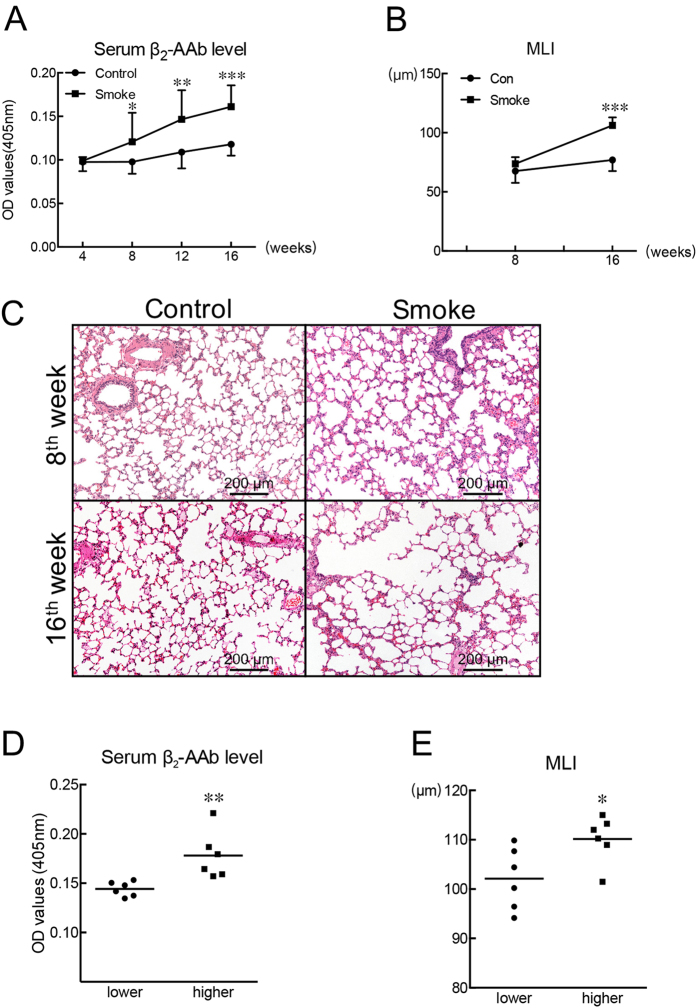

The serum β2-AAb levels of CS-exposed rats significantly increased after 8 weeks of CS-exposure, and the significant increase was maintained as CS-exposure proceeded to 16 weeks (Fig. 1A). The MLI (mean liner intercept) between the CS-exposed group and the control group showed no significant difference at the end of the 8th week (Fig. 1B and C). However, after 16 weeks of CS-exposure, the MLI was significantly higher in the CS-exposed group than in the control group (Fig. 1B and C). More statistical details can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 1. Passive-smoking rats showed higher serum β2-AAb levels than control rats before alveolar airspaces became enlarged.

(A) Levels of β2-AAb in serum samples of CS-exposed rats and control rats were assessed at different time points. SE-ELISAs were performed after rats were exposed to clean air or cigarette smoke for 4, 8, 12, or 16 weeks. (B) Statistical analyses of mean linear intercept (MLI) measurements of lung sections after rats were exposed to clean air or cigarette smoke for 8 or 16 weeks. (C) Sections of lungs from a control rat and from a CS-exposed rat sacrificed at the end of the 8th or 16th week. Haematoxylin-eosin staining, scale bar = 200 μm. (D) and (E) Lower and higher groups refer to CS-exposed rats with relatively lower and higher serum β2-AAb levels, respectively, and results of the statistical analysis of serum β2-AAb levels and MLI values of the two groups were shown in panel (D) and (E) respectively. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Control group vs Smoke group or Lower group vs Higher group (n = 18 for the Control group and Smoke group at the 4th or 8th week in panel A, n = 12 for the Control group and Smoke group at the 12 th or 16th week in panel A; n = 6 for the Control group and Smoke group at the 8th week in panel B, n = 12 for the Control group and Smoke group at the 16th week in panel B; n = 6 for the Lower group and Higher group at the 16th week in panels D and E).

CS-exposed rats with higher serum β2-AAb levels showed higher MLI values than the CS-exposed rats with lower serum β2-AAb levels

After 16 weeks of CS exposure, we divided the 12 CS-exposed rats into two subgroups, and the median value of all the serum β2-AAb levels was chosen as the cut-off value. The lower group included the 6 CS-exposed rats with relatively lower serum β2-AAb levels, and the higher group included the 6 CS-exposed rats with relatively higher serum β2-AAb levels. The higher group showed significantly higher serum β2-AAb levels (Fig. 1D) and higher MLI values (Fig. 1E) than the lower group. More statistical details can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Measurements for the active-immune and CS-exposed-active-immune rat model

Rats immunized with the ECLII peptide showed higher β2-AAb levels in their sera and emphysema-like changes in their lungs

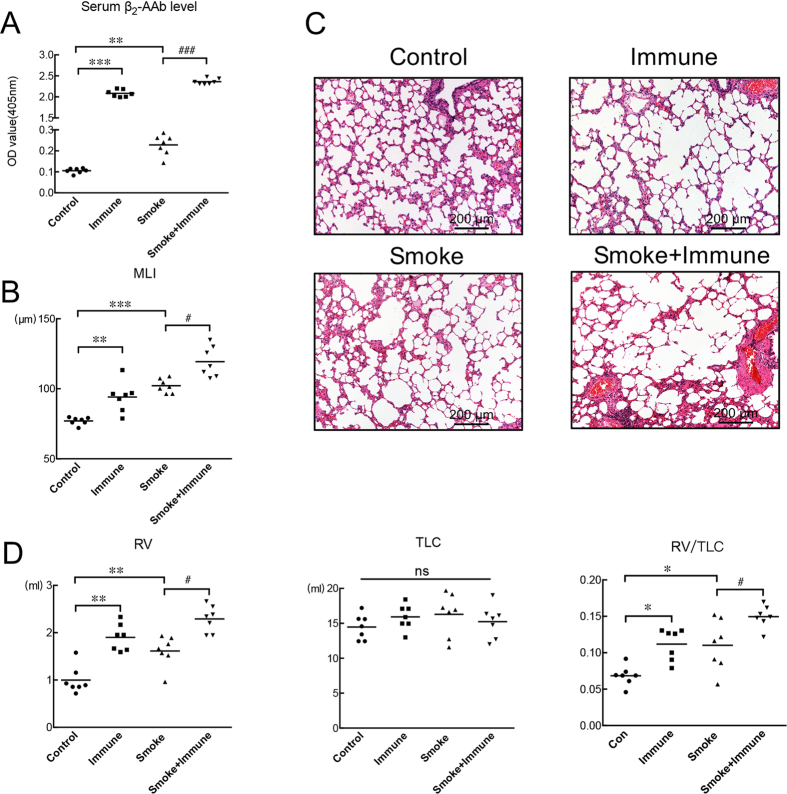

After the 16-week immunization with the β2-AR ECLII peptide, significantly increased levels of β2-AAbs were present in the sera of the rats (Fig. 2A). The lungs of rats immunized with ECLII peptides showed enlarged alveolar airspaces, and they had worse alveolar airspace destruction and increased MLI values when compared with the lungs of control rats (Fig. 2B and C). Pulmonary function test results showed that the residual volume (RV) and the RV/TLC (total lung capacity) ratio were significantly higher in the immunized group than in the control group (Fig. 2D), while TLC showed no statistical changes between the two groups (Fig. 2D). More statistical details can be found in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3.

Figure 2. Measurements after control or passive-smoking rats were immunized or not with β2-AR ECLII peptides for 16 weeks.

(A) SE-ELISAs were performed to detect the levels of β2-AAbs in the serum samples of rats from the four groups: Control group (Control), Active-Immune group (Immune), Passive-smoking group (Smoking), and Passive-smoking-active-immune group (Smoking + Immune). Analyses were conducted between the Control group and Immune group/Smoking group as well as between the Smoking group and Smoking + Immune group. (B) Lung-section MLI measurements statistical results from the Control group and Immune group as well as from Smoking group and Smoking + Immune group. (C) Section of lung from a control rat showing normal alveolar structures and sections from rats in the other three groups showing enlarged airspaces. Haematoxylin-eosin staining, scale bar = 200 μm. (D) Statistical analysis of lung function parameters (RV (residual volume), TLC (total lung capacity) and RV/TLC (residual volume/total lung capacity) ratio) between the Control group and Immune group/Smoking group as well as between the Smoking group and Smoking + Immune group. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Control group vs Immune group/Smoking group (n = 7). ###p < 0.001 and #p < 0.05; Smoke group vs Smoke + Immune group (n = 7), ns means no significant difference.

CS-exposed rats immunized with the β2-AR ECLII peptide exhibited higher serum β2-AAb levels and showed higher MLI values than the CS-exposed rats not immunized with the β2-AR ECLII peptide

After CS exposure for 16 weeks, rat showed increased serum β2-AAb levels (Fig. 2A), MLI values (Fig. 2B and C) and RVs, RV/TLC values than that in control rats (Fig. 2D). And after CS exposure and immunization with the β2-AR ECLII peptide for 16 weeks, rats showed higher serum β2-AAb levels than were found in rats only exposed to cigarette smoke (Fig. 2A). Similarly, the CS-exposed rats immunized with the β2-AR ECLII peptide showed worse alveolar airspace destruction (Fig. 2C), higher MLI values (Fig. 2B), larger RVs and higher RV/TLC ratios (Fig. 2D) than rats only exposed to cigarette smoke. TLC showed no statistical changes among the groups (Fig. 2D). More statistical details can be found in Supplementary Tables S2 and S3.

Studies on human subjects

Baseline characteristics and correlation analysis of all smokers

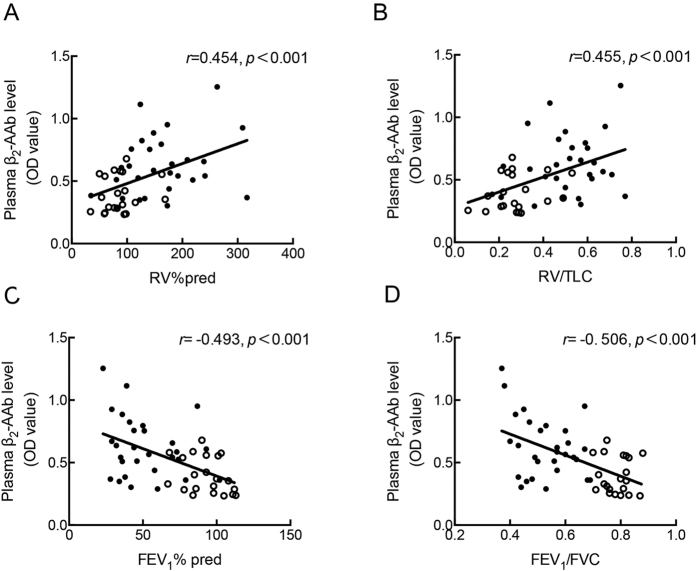

The following parameters: FEV1% pred (percent of forced expiratory volume in 1 second), FEV1/FVC (forced expiratory volume in 1 second /forced vital capacity) ratio, RV% pred (residual volume/residual volume predicted percentage) and the RV/TLC (residual volume/total lung capacity) ratio were obtained from all smokers. To assess the correlation between plasma β2-AAb levels and the parameters obtained from the lung function tests, Pearson or Spearman correlation analyses were performed, and the corresponding scatter diagrams are shown in Fig. 3. The results show that plasma β2-AAb levels were significantly and positively correlated with RV% pred (r = 0.454, p < 0.001) and the RV/TLC ratio (r = 0.455, p < 0.001) and were negatively correlated with FEV1% pred (r = −0.493, p < 0.001) and the FEV1/FVC ratio (r = −0.506, p < 0.001).

Figure 3. Correlation analysis between the plasma β2-AAb level and the lung function parameters.

Plasma β2-AAb level were positively correlated with RV% pred (A) and RV/TLC ratio(B) and negatively correlated with FEV1% pred(C) and FEV1/FVC(D) ratio in 50 smokers. RV% pred (residual volume/residual volume predicted percentage), RV/TLC (residual volume/total lung capacity), FEV1% pred (percent of forced expiratory volume in 1 second), FEV1/FVC (forced vital capacity). Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis, n = 50. The hollow dots represent smokers without COPD, and the solid dots represent those with COPD.

The multivariable multivariate linear regression model adjusted for age, BMI (body mass index), and smoking history (expressed in pack years), demonstrated that plasma β2-AAb levels were independently correlated with RV% pred, RV/TLC ratio, FEV1% pred, FEV1/FVC ratio. More statistical details can be found in Supplementary Table S4.

Subgroup studies of low-β2-AAb and high-β2-AAb smokers

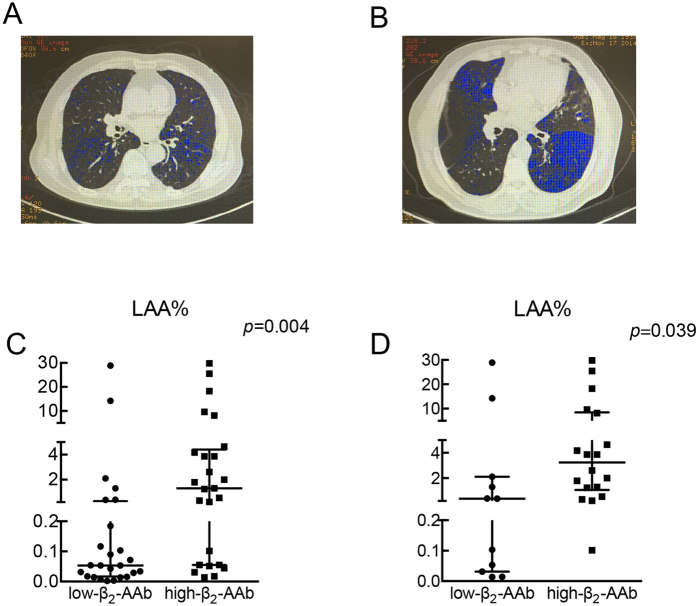

The division smokers into low-β2-AAb and high-β2-AAb groups is described in the methods. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 2 groups. Subjects in the two groups were of comparable age, BMI, and smoking history (expressed in pack-years). The high-β2-AAb smokers showed worse RV% pred, RV/TLC ratios, FEV1% pred, FEV1/FVC ratios and DLCO% pred (diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide/predicted values) than the low-β2-AAb smokers. All participants underwent HRCT (high resolution CT) scans. Additional tests compared the LAA% (low attenuation area percentage under −950 HU) values of the smokers in two subgroups. As shown in Fig. 4A–C, the high-β2-AAb smokers showed worse LAA% values than the low-β2-AAb smokers. More statistical details can be found in Supplementary Table S6.

Table 1. Comparison of demographic characteristic and clinical variables between low-β2-AAb and high-β2-AAb smokers.

| Variable | Low-β2-AAb group | High-β2-AAb group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 25 | n = 25 | ||

| Age (years) | 56 ± 13 | 62 ± 11 | 0.055 |

| FEV1% pred | 80 ± 26 | 58 ± 25 | 0.005 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.68 ± 0.13 | 0.59 ± 0.15 | 0.028 |

| RV% pred | 104 ± 58 | 156 ± 66 | 0.002 |

| RV/TLC | 0.34 ± 0.17 | 0.49 ± 0.16 | 0.002 |

| DLCO% pred | 78.16 ± 20.14 | 62.48 ± 21.46 | 0.010 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.65 ± 3.59 | 23.80 ± 3.41 | 0.898 |

| Pack years | 29 ± 18 | 36 ± 26 | 0.478 |

| Plasma β2-AAb level | 0.35 ± 0.10 | 0.70 ± 0.18 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Abbreviations: β2-AAb = β2-adrenergic receptor autoantibody; BMI, body mass index; FEV1, percent of forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1/FVC, forced expiratory volume in 1 second /forced vital capacity; RV% pred, residual volume/residual volume predicted percentage; RV/TLC, residual volume/total lung capacity. DLCO% pred, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide/predicted values. Plasma β2-AAb levels are presented as the OD values in 405 nm.

Figure 4. Smokers/COPD patients with relatively higher plasma β2-AAb levels exhibited worse LAA%.

Fifty smokers were divided into low-β2-AAb and high-β2-AAb groups. (A) and (B) show one slice of chest CT scans from a low-β2-AAb smoker (A) and a high-β2-AAb smoker (B); the blue regions in the slices indicate the low attenuation area under −950 HU. (C) and (D) show the distributions (median with interquartile range are shown) and results of the statistical analysis of the LAA% comparing low-β2-AAb and high-β2-AAb smokers (C) and COPD patients (D). (n = 25 for low-β2-AAb and high-β2-AAb smokers, n = 11 for low-β2-AAb COPD patients and n = 18 for high-β2-AAb COPD patients). HU: Hounsfield units. LAA%: the percentage of low attenuation area under −950 HU in the chest CT scans.

Subgroup studies of low-β2-AAb and high-β2-AAb COPD patients

In the low-β2-AAb group, 11 of the 50 smokers were diagnosed with COPD, and in the high-β2-AAb group, 18 were diagnosed with COPD. As shown in Table 2, the age, pack-years, and BMI values of low-β2-AAb and high-β2-AAb COPD patients did not show significant differences. The high-β2-AAb COPD patients showed significantly worse RV% pred and RV/TLC values than the low-β2-AAb COPD patients. As shown in Fig. 4D, the 18 high-β2-AAb COPD patients showed worse LAA% values than the 11 low-β2-AAb COPD patients. While the FEV1% pred, FEV1/FVC ratio and DLCO% pred showed no significance between the two groups. More statistical details can be found in Supplementary Table S6.

Table 2. Comparison of demographic characteristic and clinical variables between low-β2-AAb and high-β2-AAb COPD patients.

| Variable | Low-β2-AAb group | High-β2-AAb group | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 11 | n = 18 | ||

| Age (years) | 61 ± 13 | 65 ± 10 | 0.448 |

| FEV1% pred | 59 ± 25 | 47 ± 18 | 0.121 |

| FEV1/FVC | 0.56 ± 0.10 | 0.51 ± 0.09 | 0.197 |

| RV% pred | 129 ± 75 | 181 ± 56 | 0.013 |

| RV/TLC | 0.43 ± 0.18 | 0.56 ± 0.12 | 0.030 |

| DLCO% pred | 67.18 ± 21.87 | 57.67 ± 20.89 | 0.252 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.47 ± 3.05 | 23.60 ± 3.28 | 0.363 |

| Pack years | 38 ± 21 | 41 ± 28 | 0.787 |

| Plasma β2-AAb level | 0.41 ± 0.10 | 0.75 ± 0.19 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD. Abbreviations: β2-AAb = β2-adrenergic receptor autoantibody; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; BMI, body mass index; FEV1% pred, percent of forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FEV1/FVC, forced expiratory volume in 1 second /forced vital capacity; RV% pred, residual volume/residual volume predicted percentage; RV/TLC, residual volume/total lung capacity, DLCO% pred, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide/predicted values. Plasma β2-AAb levels are presented as the OD values in 405 nm.

Discussion

In the present study, we firstly demonstrated the presence and increased expression of β2-AAbs against the second extracellular loop of the β2-AR in rats with CS-exposure-induced emphysema. We found that serum β2-AAb levels significantly increased before alveolar airspaces became enlarged in CS-exposed rats, and CS-exposed rats with higher serum β2-AAb levels had higher MLI values than CS-exposed rats with lower serum β2-AAb levels. In the active-immune rat model, we found significantly increased serum β2-AAb levels in immunized rats, and the immunized rats showed larger MLI and RV values and RV/TLC ratios than the control rats. The rats subjected to both CS-exposure and immune activation showed larger MLI values and RV/TLC ratios than the rats subjected only to CS-exposure. In our clinical studies, we observed that plasma β2-AAb levels showed a significant and positive correlation with RV% pred and RV/TLC ratios among smokers. Both smokers and COPD patients with higher plasma β2-AAb levels showed higher RV%, RV/TLC ratio and LAA% values than smokers or COPD patients with lower plasma β2-AAb levels. Based on the results in both humans and rats, we suggest that circulating β2-AAbs are associated with alveolar destruction and increases in RV.

Our study was primarily based on animal models. We previously reported the effectiveness of 16 weeks of CS-exposure in inducing emphysema and COPD-like changes based on the pathological and pulmonary function changes that occur in rat lungs13,20. In this study, we used this model to analyse whether β2-AAb levels are increased before the development of smoking-induced emphysema. In addition, studies on β1-adrenergic receptor (β1-AR) autoantibodies (β1-AAbs) have indicated that active immunization with synthetic peptides corresponding to the second extracellular loop of the β1-AR induces a marked production of β1-AAbs, which have similar biological and immunological properties as in the plasma of DCM (dilated cardiomyopathy) patients21. Therefore, a rat model of active immunization using a synthetic peptide corresponding to the ECLII of the rat β2-AR was established to perform additional investigations in vivo. Using the active-immune rat model, our previous studies have shown that the injection of the adjuvant alone has no effect on lung structure or function. In this study, we thoroughly mixed the peptide with the adjuvant and repeatedly injected the mixture into rats to maintain β2-AAb production throughout the experimental period. We found that CS-exposed rats immunized with the β2-AR ECLII peptide, who had higher serum β2-AAb levels, exhibited more extensive alveolar airspace destruction than rats subjected only to CS-exposure. CS-exposed rats with higher serum β2-AAb levels showed higher MLI values than CS-exposed rats with lower serum β2-AAb levels. These findings are in accordance with the findings of our clinical study showing that high-β2-AAb smokers and COPD patients were found to have larger LAA% values. These data indicate that β2-AAbs may be involved in the destruction of alveolar airspaces.

Previous studies have found that age, smoking history (in pack-years) and BMI are all related to autoantibody production and lung function in COPD and emphysema patients7. In our subgroup analysis, all of these parameters were matched between the groups, and all subjects were current male smokers, so the effects of smoking status and gender were also avoided. Moreover, age, BMI (body mass index), smoking history (expressed in pack years) were also adjusted in the multivariable multivariate linear regression model, which strengthened our study. In addition, lung function tests and CT scans were performed, which provided stronger evidence to support our findings. Smoking exposure is able to provoke oxidative stress and upregulate immune genes, thereby leading to autoimmune responses. Immune responses in smokers vary, and the identity and nature of the antigens that drive the production of autoantibodies in smokers remains unknown. In COPD, lymphoid follicles in the lungs may be the result of smoke exposure, and they are associated with disease severity. B cells are the predominant cell type in these follicles, and the proliferation of B cells within the germinal centres of these follicles shows antigen-specific characteristics22. Carbonyl-modified proteins may be the result of long-term smoke exposure, and studies have indicated that levels of antibodies against carbonyl-modified proteins correlate with the severity of COPD23. Our previous studies also indicated that long-term smoke exposure affected the expression of β2-ARs in the lung20. However, whether this is the source of self-antigens still needs to be determined.

Some autoantibodies found in association with emphysema or COPD have been shown to have little clinical or pathological importance. Previous observational studies have demonstrated higher titres of circulating antinuclear antibodies and anti-tissue antibodies in some COPD patients, and only anti-tissue antibodies were found to be related to impaired lung function, but the underlying mechanism has not been studied further3. A previous study also showed an increased expression of xenogeneic EC autoantibodies. Rats injected intraperitoneally with xenogeneic ECs were found to produce antibodies against ECs, and active immunization with ECs or the passive injection of anti-EC autoantibodies induced emphysema and cell apoptosis. In addition, MMP-9 and MMP-2 activation were found to take part in this process24. Currently, protease/anti-protease imbalances and cell apoptosis in the lungs are all proposed as major mechanisms resulting in emphysema, and MMP-9 has been recognized as one of the important elastases that contribute to the development of emphysema25. Common autoantibodies induce regular immune responses, leading to the destruction of the affected tissue, whereas autoantibodies target adrenergic receptors showing functional activity15. Numerous studies have shown that DCM patients may produce β1-AAbs, which bind to and activate the receptor, provoking biological responses related to the pathogenesis of DCM26,27,28,29,30. β1-AAbs may induce cell death in vitro, whereas the neutralization of β1-AAb aptamers has a protective effect against cell death. In vivo, the application of immunoadsorption to remove β1-AAbs from the blood of DCM patients has long-lasting benefits, including a higher left ventricular ejection fraction28, less oxidative stress29, and a better 5-year survival rate30. Only a few studies have focused on β2-AAbs. These studies have indicated that one type of human monoclonal β2-AAb against the N terminus of the ECLII peptide displays agonist-like functions in vitro31. The activation of β2-ARs is likely to have beneficial effects for relieving airflow limitations, although the activation of β2-ARs in the absence of pro-inflammatory stimuli has been shown to produce increased IL-1β and IL-6 transcripts in macrophage cell lines10. Macrophages play important roles in the development of emphysema, and IL-6 and IL-1β are both involved in emphysema32. Salbutamol, a β2-AR agonist, has been shown to promote MMP-9 expression in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of ARDS patients33. However, classical β-AR agonists and the β-AR autoantibodies have different binding sites (hydrophobic pockets and extracellular loops, respectively)15, and the β2-AAbs identified in our study were polyclonal antibodies. Determining the exact functions of β2-AAbs in vivo needs further investigation.

DLCO% pred, which assesses the potential of the lung for gas exchange, is decreased when alveolar airspaces are damaged in smokers34,35. We found that the plasma β2-AAb levels in smokers were correlated with DLCO% pred and not with β1-AAbs (see Supplementary Table S4 and S6), and smokers wither higher plasma β2-AAb levels showed worse DLCO% pred, which may indicate more extensive alveolar airspace damage. We also noticed than in our correlation studies, plasma β2-AAbs in smokers were negatively correlated with FEV1 and the FEV1/FVC ratio. However, in additional studies, we found that that plasma β1-AAbs in smokers were also negatively correlated with FEV1% pred, but were not significantly correlated with RV% pred and the RV/TLC ratio (see Supplementary Fig. S3). In addition, we found that the β1-AAbs were not significantly greater in passive-smoking rats than in control rats after CS-exposure for 16 weeks (see Supplementary Fig. S1). Considering the similarity of our results with those of a study focusing on the relationships between autoantibodies and lung function36, the autoantibodies associated with emphysema may be antigen specific. We noticed that the serum β2-AAb levels in active-immune rats were much higher than those in passive-smoking rats, while the morphological analysis and lung function tests did not indicate worse alveolar airspace destruction in the active-immune groups than in the passive-smoking rats. However, we did notice that passive smoking rats immunized with ELCII peptide exhibited worse RV% pred, RV/TLC and MLI values than rats subjected to passive-smoking alone. Passive-smoking and active-immune stimulation may involve different pathophysiological processes.

TLC is composed of several parts, such as residue volume and the IC (inspiratory capacity) values. According to a previous study34, the destruction of alveolar airspace may or may not be associated with airflow limitation, and RV is generally the first to increase, followed by other parameters, such as TLC37. In our clinical studies, we did notice that smokers with higher plasma β2-AAb levels exhibited worse FEV1/FVC and FEV1% pred. Because of limited applications in rat lung function tests, the relationship between β2-AAbs and airflow limitation needs further study. At the same time, we notice that the IC/TLC value may reflect the lung hyperinflation38. And our results in animals are in accordance with the study that the CS-exposed rats immunized with β2-AR ECLII peptide showed decreased IC/TLC values than CS-exposed rats (see Supplementary Fig. S2).

There are limitations in this study that should be noted. 1) The homology of the peptide sequence of the ECLII of the β1-AR between humans and rats was 100%, whereas the homology of the β2-AR ECLII sequence was 98%. 2) It is not yet clear how to effectively influence the production of β2-AAbs, and although neutralized peptides proved to be useful in vitro, their use would induce more β2-AAb production in vivo. 3) Considering that the majority of COPD and emphysema patients in our country are male smokers, our clinical study was based on a relatively small sample of male smokers, and whether the effects of β2-AAbs are related to gender needs further study. 4) In addition, whether β2-AAb expression increases and is involved in COPD-related diseases in non-smokers or in genetics-based emphysema, such as that caused by an alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency, are not known.

Our study extends the knowledge of the relationships of autoantibodies with emphysema and COPD, which will benefit future studies. We suggest that higher circulating β2-AAb levels may be associated with worse alveolar airspace destruction, and may aggravate smoking-related lung injuries. Our research suggests that β2-AAbs may act as a biomarker for increased alveolar airspace destruction in male smokers, which may help in identifying new therapies for treating emphysema.

Methods

Animal model

Protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments of Peking University (permit No: LA2010-004), and the methods were strictly carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Rats were obtained from the animal centre of Peking University Health Science Centre and were housed as previously reported13. Thirty-six male Sprague-Dawley rats (SD rats, 7 weeks old) were used in our preliminary test of the passive-smoking model: (1) eighteen Control rats were housed in clean air and were not subjected to CS-exposure; and (2) eighteen CS-exposed rats were exposed to the smoke from 30 cigarettes (Du Bao brand, China) twice per day, 6–7 times per week, from the 1st to the 8th or 16th week using the BUXCO animal CS-exposure system (DSI, USA). Six control rats and six passive-smoking rats were sacrificed at the end of the 8th week and others were sacrificed at the end of the 16th week. In the passive-smoking-active-immune model, twenty-eight male SD rats (7 weeks old) were divided into 4 groups: (1) seven Control rats were housed in clean air and were not subjected to CS-exposure or peptide injections; (2) seven CS-exposed rats were exposed to smoke as described above; (3) seven rats in the active-immune group were housed with clean air and were given hypodermic injections of rat β2-AR ECLII peptides (1 μg/100 g, synthesized by a contractor: Shanghai GL Biochem. Ltd. China) combined with a complete adjuvant (Sigma, USA) for the first injection and with an incomplete adjuvant (Sigma, USA) for subsequent injections, which were repeated twice a week from the 1st to the 16th week; and (4) seven rats were exposed to both cigarette smoke and administered β2-AR ECLII peptide immunizations from the 1st to the 16th week. Measurements of the mean linear intercept (MLI) in rats were performed as previously reported24.

Lung function in rats

The equipment was calibrated before use39. Rats were anaesthetized with 1% pentobarbital sodium (0.4 mg/100 g, intra-peritoneal injection; Sigma, USA) prior to surgery. Tracheostomies were performed with a standard catheter provided with the Buxco equipment (DSI, USA). Rats were placed in a body plethysmograph and connected to a computer-controlled ventilator after tracheostomy.

Peptide synthesis

The peptides corresponding to the sequence (amino acid residues 172–198) of the ECLII peptide of the human β2-AR (H-W-Y-R-A-T-H-Q-E-A-I-N-C-Y-A-N-E-T-C-C-D-F-F-T-N-Q-A), rat β2-AR (H-W-Y-R-A-T-H-K-Q-A-I-D-C-Y-A-K-E-T-C-C-D-F-F-T-N-Q-A) and β1-AR (H-W-W-R-A-E-S-D-E-A-R-R- C-Y-N-D-P-K-C-C-D-F-V-T-N-R-C) were synthesized using an automated peptide synthesizer via solid-phase methods. Peptide purity was assessed via high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) using an automated amino-acid analyser. Peptide preparations were found to be 98% pure. The process was performed by a contractor: Shanghai GL Biochem, China.

Rats tissue treatment and the collection of serum samples

Blood samples were taken from rats via the vessels in their tails every four weeks during the experiment or from the abdominal aorta before rats were sacrificed and were centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes at 4 °C without an anticoagulant to obtain serum samples. Serum samples were stored at −80 °C until further study. At each time point, the serum β2-AAb levels of rats were assessed via SE-ELISA. The left lobe of the lung of each rat was clamped at the hilum and preserved in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological analysis. Lung tissues were embedded in paraffin and stained with haematoxylin and eosin for pathological analyses.

SE-ELISA

Fifty microliters of ECLII peptide (5 μg/ml) in a 0.1 M Na2CO3 solution (pH 11.0) was coated onto a 96-well microplate overnight at 4 °C. The wells were then saturated with PBS supplemented with 5% bovine serum and 0.1% Tween 20 (PMT). Human plasma samples were diluted 80 times, and rat serum samples were diluted 10,000 times before use. Fifty microliters of diluted/undiluted samples in PMT were allowed to react with the peptide for 1 hour at 37 °C. After washing three times with PBS (including 0.05% Tween 20, washing buffer), 0.05 ml of biotinylated rabbit anti-human/rat IgG antibody (1:1000 dilution in PMT) was added and allowed to react for 1 hour at 37 °C. After three washes, the bound biotinylated antibody was detected following the incubation of the plates with a streptavidin-peroxidase (1 μg/ml) solution in PMT for 1 hour. This was followed by three washes and the addition of the substrate (2.5 mmol/L H2O2, 2 mmol/L ABTS, Sigma, USA). Optical densities (ODs) were read at 405 nm after 30 minutes in a standard microplate spectrophotometer and were used to indicate the level of β2-AAbs according to the researches in β1-AAbs40 and other autoantibodies24,41. All samples were measured in duplicate wells, and the average values were used. One sample was selected for inclusion on each ELISA plate to control for interassay variability.

Study population and emphysema assessment

Peking University Third Hospital Research and Development Department approved the study protocol (NO. IRB00001052-08089), and the methods were strictly carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. Sixty-five male current smokers were recruited between October and December 2014. Individuals who had an α1-anti-trypsin deficiency, a history of physician-diagnosed asthma and other autoimmune diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Crohn’s disease), Chagas’ cardiomyopathy, open-angle glaucoma or regional pain syndrome were excluded from the study. COPD patients were also excluded if they had experienced an exacerbation of the disease within the previous 6 weeks. Individuals were also excluded if they refused to perform chest CT scans. At last, fifty individuals were recruited for further studies. Of the 50 male current smokers in this study, 29 were classified as having COPD, and 21 were defined as smokers without airway flow restriction. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Data on age, height, weight, and smoking history were collected by asking the subjects. FEV1% pred, RV% pred, and the FEV1/FVC and RV/TLC ratios were measured via pulmonary function tests (Sensor Medics, Yorba Linda, CA, USA). All participants underwent chest CT scans, and the percentage of the low attenuation area below −950 Hounsfield units (HU)42 (LAA%) was measured using AW version 4.5 software (GE healthcare, Fairfield, CT, USA) to determine the extent of emphysema. Diagnoses of COPD followed the guidelines of the Global Initiative for COPD (GOLD), which were revised in 2016. Blood samples (approximately 4 ml) were collected from all participants via an antecubital vein into a vacuum tube containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and were centrifuged at room temperature within half an hour from the time of collection. The separated plasma samples were aliquoted into sterile microcentrifuge tubes (500 μl in each vial) and then stored at −80 °C. In addition, we used SE-ELISAs to determine the plasma β2-AAb levels in each sample after a dilution of 1:80. The median of all plasma β2-AAb values (OD values at 405 nm) were used as the cut-off value to divided the smokers into two sub-groups: the low-β2-AAb group and the high-β2-AAb group. Flow diagram of the study can be found in Supplementary Figure S4.

Data analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± SD or mean values with individual data points and were analysed for statistical significance using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad) and SPSS 11.5. The results with a p < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Shapiro-Wilk tests were applied to assess the normality of the distribution of continuous variables in each group. In addition, Levene’s tests were applied to assess the homogeneity of variance. If the p values for both tests were greater than 0.05, T-tests or ANOVAs were conducted. Direct comparisons between two groups were performed using non-parametric Mann-Whitney tests (between two groups) or Kruskal-Wallis H tests (more than two groups) when the data sets were not normally distributed. In clinical studies, correlation analyses were performed using the Pearson or Spearman method; multivariate linear regression model were also employed to adjust the effect of confounders.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Hu, J.-y et al. Increased circulating β2-adrenergic receptor autoantibodies are associated with smoking-related emphysema. Sci. Rep. 7, 43962; doi: 10.1038/srep43962 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Lei Guo (Peking Union Medical College, Beijing, China) for help with the rat pulmonary function tests, and Dan-dan Miao, Li-yuan Tao for statistical works. This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81270097; 81470235; No. 81670034) and the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing Municipality (No. 7112745). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions Bei He, Ming Xu and You-yi Zhang conceived and designed the study. Jia-yi Hu participated in both the clinical and animal studies and drafted the manuscript. Bei He, Bei-bei Liu and Yi-peng Du helped design and participated in the clinical studies. Bei He and Ming Xu helped in drafting the manuscript. Yuan Zhang and Yi-wei Zhang participated in the animal studies.

References

- Rennard S. I. et al. Identification of five chronic obstructive pulmonary disease subgroups with different prognoses in the ECLIPSE cohort using cluster analysis. Annals of the American Thoracic Society 12, 303–312, doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201403-125OC (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerassimov A. et al. The development of emphysema in cigarette smoke-exposed mice is strain dependent. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 170, 974–980, doi: 10.1164/rccm.200309-1270OC (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez B. et al. Anti-tissue antibodies are related to lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 183, 1025–1031, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0029OC (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette M. C. et al. Persistence of pulmonary tertiary lymphoid tissues and anti-nuclear antibodies following cessation of cigarette smoke exposure. Respiratory research 15, 49, doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-49 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraseviciene-Stewart L. et al. Is alveolar destruction and emphysema in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease an immune disease? Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 3, 687–690, doi: 10.1513/pats.200605-105SF (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattioni M. et al. Serum p53 antibody detection in patients with impaired lung function. BMC cancer 13, 62, doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-62 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonarius H. P. et al. Antinuclear autoantibodies are more prevalent in COPD in association with low body mass index but not with smoking history. Thorax 66, 101–107, doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.134171 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard T. A. et al. COPD is associated with production of autoantibodies to a broad spectrum of self-antigens, correlative with disease phenotype. Immunologic Research 55, 48–57, doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8347-x (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spina D. et al. Autoradiographic localization of beta-adrenoceptors in asthmatic human lung. The American review of respiratory disease 140, 1410–1415, doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.5.1410 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan K. S. et al. Beta2 adrenergic receptor activation stimulates pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages via PKA- and NF-kappaB-independent mechanisms. Cellular signalling 19, 251–260, doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.06.007 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu G. M. & Factor P. Alveolar epithelial beta2-adrenergic receptors. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology 38, 127–134, doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0198TR (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M. et al. beta2-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms, asthma and COPD: two large population-based studies. The European respiratory journal 39, 558–566, doi: 10.1183/09031936.00023511 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. et al. beta2-Adrenoceptor involved in smoking-induced airway mucus hypersecretion through beta-arrestin-dependent signaling. PloS one 9, e97788, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097788 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. et al. Fenoterol inhibits LPS-induced AMPK activation and inflammatory cytokine production through beta-arrestin-2 in THP-1 cell line. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.097 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallukat G. & Schimke I. Agonistic autoantibodies directed against G-protein-coupled receptors and their relationship to cardiovascular diseases. Seminars in immunopathology 36, 351–363, doi: 10.1007/s00281-014-0425-9 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter J. C. et al. Autoantibodies to beta 2-adrenergic receptors: a possible cause of adrenergic hyporesponsiveness in allergic rhinitis and asthma. Science 207, 1361–1363 (1980). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohr D. et al. Autoimmunity against the beta2 adrenergic receptor and muscarinic-2 receptor in complex regional pain syndrome. Pain 152, 2690–2700, doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2011.06.012 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karczewski P. et al. Agonistic autoantibodies to the alpha(1) -adrenergic receptor and the beta(2) -adrenergic receptor in Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia. Scandinavian journal of immunology 75, 524–530, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2012.02684.x (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y. et al. Effects of one month treatment with propranolol and metoprolol on the relaxant and contractile function of isolated trachea from rats exposed to cigarette smoke for four months. Inhalation toxicology 26, 271–277, doi: 10.3109/08958378.2014.885098 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y. et al. Effects of long-term application of metoprolol and propranolol in a rat model of smoking. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology 41, 708–715, doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12261 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y. et al. beta1 -adrenergic receptor autoantibodies from heart failure patients enhanced TNF-alpha secretion in RAW264.7 macrophages in a largely PKA-dependent fashion. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry 113, 3218–3228, doi: 10.1002/jcb.24198 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seys L. J. et al. Role of B Cell-Activating Factor in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 192, 706–718, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201501-0103OC (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraseviciene-Stewart L. & Voelkel N. F. Oxidative stress-induced antibodies to carbonyl-modified protein correlate with severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 185, 1026; author reply 1026–1027, doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.185.9.1026 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taraseviciene-Stewart L. et al. An animal model of autoimmune emphysema. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 171, 734–742, doi: 10.1164/rccm.200409-1275OC (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharafkhaneh A. et al. Pathogenesis of emphysema: from the bench to the bedside. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society 5, 475–477, doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-126ET (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagatomo Y. et al. Presence of autoantibody directed against beta1-adrenergic receptors is associated with amelioration of cardiac function in response to carvedilol: Japanese Chronic Heart Failure (J-CHF) Study. Journal of cardiac failure 21, 198–207, doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.12.005 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y. et al. Autoantibody against cardiac beta1-adrenoceptor induces apoptosis in cultured neonatal rat cardiomyocytes. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica (Shanghai) 38, 443–449 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller J. et al. Immunoglobulin adsorption in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation 101, 385–391 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schimke I. et al. Reduced oxidative stress in parallel to improved cardiac performance one year after selective removal of anti-beta 1-adrenoreceptor autoantibodies in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy: data of a preliminary study. Journal of clinical apheresis 20, 137–142, doi: 10.1002/jca.20050 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessel F. P. et al. Economic evaluation and survival analysis of immunoglobulin adsorption in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. The European Journal of Health Economics 5, 58–63, doi: 10.1007/s10198-003-0202-5 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. Implications of a vasodilatory human monoclonal autoantibody in postural hypotension. J Biol Chem 288, 30734–30741, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.477869 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetley T. D. Macrophages and the pathogenesis of COPD. Chest 121, 156S–159S (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Kane C. M. et al. Salbutamol up-regulates matrix metalloproteinase-9 in the alveolar space in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Critical care medicine 37, 2242–2249, doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a5506c (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcaide A. B. et al. Clinical Features of Smokers with Radiological Emphysema but without Airway Limitation. Chest, doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.044 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey B. G. et al. Risk of COPD with obstruction in active smokers with normal spirometry and reduced diffusion capacity. The European respiratory journal 46, 1589–1597, doi: 10.1183/13993003.02377-2014 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunez B. et al. Anti-tissue antibodies are related to lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 183, 1025–1031, doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0029OC (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino R. & Brusasco V. On the causes of lung hyperinflation during bronchoconstriction. The European respiratory journal 10, 468–475 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French A., Balfe D. et al. The inspiratory capacity/total lung capacity ratio as a predictor of survival in an emphysematous phenotype of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. International journal of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 10, 1305–1312, doi: 10.2147/COPD.S76739 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vleeschauwer S. I. et al. Repeated invasive lung function measurements in intubated mice: an approach for longitudinal lung research. Laboratory Animals 45, 81–89, doi: 10.1258/la.2010.010111 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. Inducible cardiac arrhythmias caused by enhanced beta1-adrenergic autoantibody expression in the rabbit. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology 306, H422–428, doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00551.2013 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene C. M. et al. Anti-proline-glycine-proline or antielastin autoantibodies are not evident in chronic inflammatory lung disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine 181, 31–35, doi: 10.1164/rccm.200904-0545OC (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. et al. Optimal threshold in CT quantification of emphysema. European Radiology 23, 975–984, doi: 10.1007/s00330-012-2683-z (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.