Abstract

Wolbachia pipientis is an insect endosymbiont known to limit the replication of viruses including dengue and Zika in their primary mosquito vector, Aedes aegypti. Wolbachia is being released into mosquito populations globally in a bid to control the diseases caused by these viruses. It is theorized that Wolbachia’s priming of the insect immune system may confer protection against subsequent viral infection. Other hypotheses posit a role for competition between Wolbachia and viruses for host cellular resources. Using an A. aegypti cell line infected with Wolbachia, we tested the effects of targeting siRNAs against the major innate immune pathways on dengue virus loads. We show that while Wolbachia infection induces genes in the Toll, JAK/STAT and RNAi pathways, only reduced expression of RNAi leads to a rebound of dengue virus loads in Wolbachia-infected cells. The magnitude of the effect explained less than 10% of the total DENV load, demonstrating that blocking must be dependent on other factors in addition to the expression of RNAi. The findings bode well for the long-term stability of blocking given that immunity gene expression would likely be highly plastic and susceptible to rapid evolution.

Arthropod-borne diseases, mainly those transmitted by mosquitoes, are one of the leading causes of mortality in humans, especially in tropical and subtropical areas1. Dengue virus (DENV, serotypes 1–4) is a positive single stranded RNA virus of the family Flaviviridae and the causative agent of dengue fever, a debilitating illness and the most prevalent of all arthropod-borne diseases worldwide2,3. Current estimates suggest upwards of 400 million people are at risk of becoming infected annually4,5. DENVs are transmitted to humans during blood feeding by female Aedes mosquitoes: Aedes aegypti is the main vector and, to a lesser extent, Aedes albopictus2,6,7.

The virus is spreading quickly due to globalization8 and climate change9, which is allowing Aedes spp. to colonise traditionally colder regions. Current vaccines are imperfect10,11 and there are no effective antivirals. Additionally, the severity of outbreaks appears to be increasing12. More recently, Zika virus, also vectored by A. aegypti, has re-emerged with devastating health and socioeconomic impact worldwide13,14. Current strategies for limiting arthropod-borne diseases are heavily dependent on effective vector control4. The most novel of these type of approaches relies on the use of an insect bacterial endosymbiont, Wolbachia, that has the capacity to limit the replication of arboviruses inside mosquito vectors15.

Wolbachia pipientis is vertically transmitted by females to their offspring and drives its own spread through insect populations by manipulating host reproductive success to its own advantage16. The ability to invade a population and be self-sustaining is hugely appealing with respect to its potential use for biological control. Not native to most of the major insect vectors, Wolbachia had to be transinfected from Drosophila melanogaster into A. aegypti, where it then formed a stably inherited infection17. The ability of Wolbachia to spread into native A. aegypti populations and remain at high frequencies was first demonstrated in Cairns, Australia18. Wolbachia also has been shown to reduce the replication of a range of pathogens inside insects including viruses, bacteria, nematodes and the malaria parasite19,20,21,22. Subsequently, release programs have begun in multiple locations throughout the tropics.

Despite the global scale of Wolbachia’s release, the mechanism of Wolbachia-based ‘pathogen blocking’ is not well understood. Modulations of essential cellular components such as cholesterol23 and host microRNAs24, as well as competition between pathogens and Wolbachia for limited host resources21 have been theorized to underpin blocking. It has also been suggested that the diversity of pathogens blocked by Wolbachia could be explained by a Wolbachia-mediated host gene modulation leading to an increase in the basal immune activity of the host21,22. Any subsequent exposure to a pathogen would therefore lead to greater ability to control the assault, in a theory deemed ‘innate immune priming’25,26.

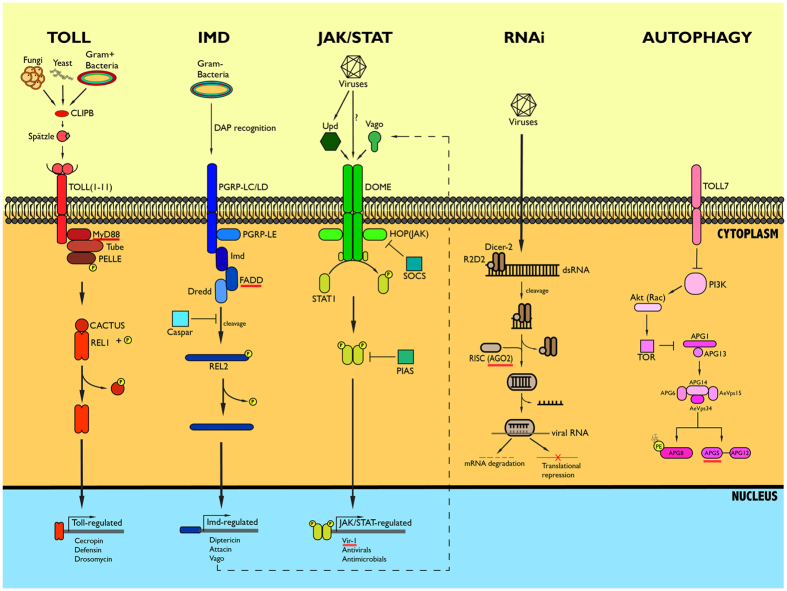

The primary humoral pathways of the insect innate immune response include Toll, Immune Deficiency (Imd), Janus Kinase-Signal Transducer Activator of Transcription (JAK/STAT) and the exogenous siRNA pathway as part of the RNAi response (Fig. 1)27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Additionally, there are cellular responses including the Toll-induced autophagy pathway and melanization cascades34,35. Each of the pathways has some specificity with respect to type of pathogen targeted, i.e. bacteria, viruses or fungi but several of the pathways are not yet completely defined and there is a growing evidence of overlap between pathways classified as antimicrobial or antiviral36,37. For example, the Toll and Imd pathways are primarily antibacterial in effect, but Toll is also required for the mosquito’s response to DENV38,39.

Figure 1. The main Aedes aegypti innate immune pathways,

The Toll, Imd, JAK/STAT, RNAi and Autophagy. All genes shown correspond to the A. aegypti relationships and nomenclature. Underlined genes are targeted with siRNA in this study.

Multiple studies have demonstrated that Wolbachia infection increases the basal expression of innate immunity genes22,25,26. In D. melanogaster, Wolbachia does not induce the Toll and Imd pathways. Regardless, there is some evidence of Wolbachia-mediated blocking when DENV is injected into the fly, suggesting these pathways are not required40. Immune activation by Wolbachia in the mosquito, however, is stronger and more widespread in terms of genes and pathways affected26,41,42. This difference in the nature of immune activation may also explain the much broader spectrum of pathogen blocking seen in the mosquito including antibacterial and antiviral effects42. Few studies have addressed the role of the primary antiviral pathways JAK/STAT and RNAi, or cellular responses like autophagy in regards to Wolbachia-mediated blocking in mosquitoes43.

The induction of the JAK/STAT pathway has been shown to restrict infection of another flavivirus, West Nile virus, in Culex mosquitoes44 and the malaria parasite in Anopheles gambiae45. In A. aegypti, the antiviral function of the pathway is conserved with high activation levels of JAK/STAT limiting DENV replication. The effectors of this pathway, however, are poorly characterized32. RNAi is considered one of the major antiviral pathways, shown to limit DENV, chikungunya and Sindbis viruses in A. aegypti29,46,47 but seems less important for pathogen blocking in insects with native Wolbachia infections48,49. The RNAi pathway is initiated with the recognition and cleavage of viral double stranded RNA (dsRNA) into siRNAs that then operate through cellular machinery to degrade viral ssRNA. Lastly, the cellular responses of autophagy33,50 and apoptosis also have some antiviral relevance51,52.

In this study we investigated which components of the mosquito innate immune response are both primed by Wolbachia and are essential to induce DENV blocking. We focused on each of the above mentioned major pathways, selecting genes to represent pathways that were either starting points in a signaling cascade, like MyD88 (Toll) and FADD (Imd), or because they serve as effectors, like vir-1 (JAK/STAT), argonaute-2 (AGO2, RNAi) and APG5 (autophagy). We then examined the functional role of each associated pathway in DENV control in A. aegypti cells by manipulating gene expression via targeted RNAi techniques in both Wolbachia-infected and Wolbachia-free cells. We predicted that if genes were uninvolved in Wolbachia-mediated effects, reducing their expression via siRNA treatment should have little impact on DENV loads in Wolbachia-infected cells. In contrast, if the Wolbachia-mediated blocking was reliant on the activity of particular genes, DENV loads should rebound after siRNA treatment. We were particularly interested in genes exhibiting this pattern, whose basal expression was also enhanced by Wolbachia.

Results

To gauge the relative contribution of each of the immune pathways to Wolbachia-mediated DENV blocking, candidate genes for each pathway were knocked down in an A. aegypti embryonic cell line infected with Wolbachia and a tetracycline treated version of the same line (Aag2 ± wMel) that served as a Wolbachia-free control. Reductions in gene expression were confirmed 18 h post-transfection. Cell lines were then challenged with a DENV-2 strain to assess whether reduced activity of each immune pathway lead to a corresponding increase in DENV load at 5 days post-infection. In two cases (MyD88 and FADD) where selected genes were early in the pathway, we also assessed whether expression changes were carried through to effectors. To assess whether the different pathways have an additive effect on inhibiting DENV replication, we performed consecutive treatments with siRNA for pairs of genes prior to the challenge with DENV-2. We first showed that transfection with a non-Aedes targeted siRNA did not alter gene transcription levels so it could be used as a transfection control across samples (Fig. S1). We also demonstrated that single and successive paired siRNA treatment had no effect on Wolbachia densities (Fig. S2).

Toll and Imd

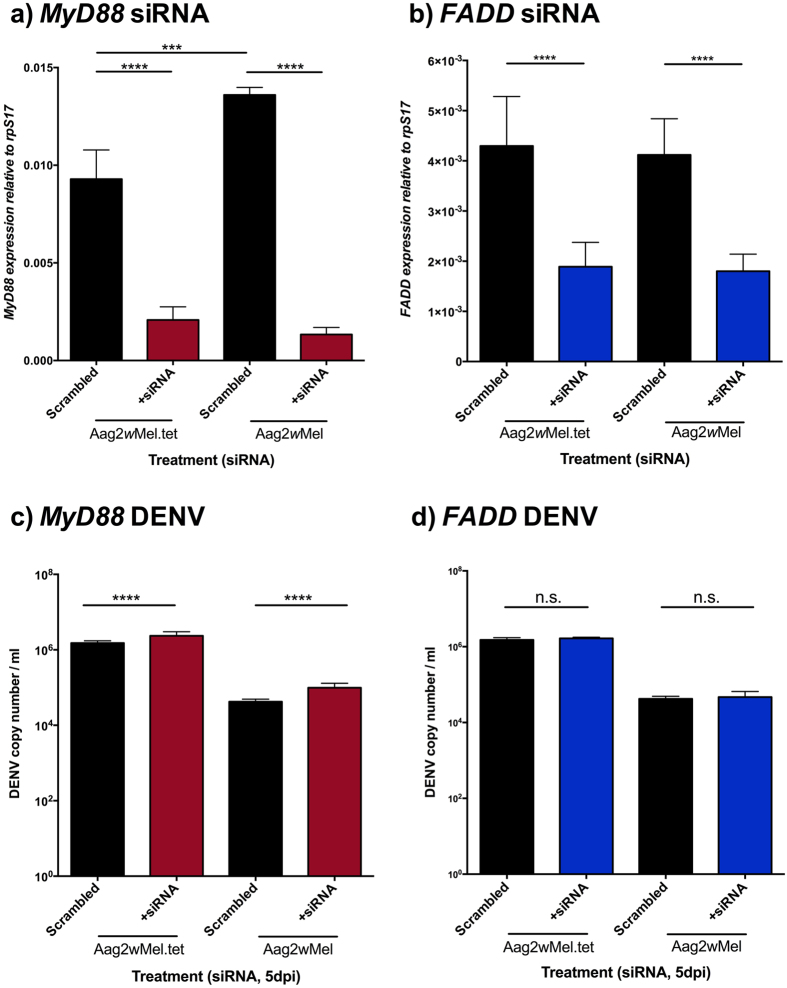

Both Wolbachia infection (F = 10.23, df = 1, p = 0.003) and siRNA treatment (F = 611.94, df = 1, p < 0.0001) had significant effects on MyD88 expression. Posthoc comparisons demonstrated reductions in MyD88 expression (Fig. 2a) between the treatment and scrambled control for both Aag2wMel.tet (t = 20.03, df = 20, p < 0.0001) and Aag2wMel (t = 14.52, df = 20, p < 0.0001). Concurrent reductions in expression of genes downstream in the Toll pathway demonstrate the generality of the effect (Fig. S3). A direct comparison of the expression levels in the scrambled treatment across lines revealed differences (t = 4.65, df = 20, p = 0.0002) that may be explained by Wolbachia infection as well as effects of the antibiotic treatment or drift in the post antibiotic passaging period. This reinforces the need to examine fold changes in expression after siRNA treatment relative to the scrambled control to correct for line effects. This difference may also highlight up-regulation by Wolbachia of immunity genes in keeping with the immune priming hypothesis25. In comparison, relative to scrambled controls, the magnitude of the reduction in MyD88 expression was roughly 4.5-fold in the Aag2wMel.tet and 9-fold in Aag2wMel. In the case of FADD expression, siRNA treatment (F = 86.73, df = 1, p < 0.0001) had a significant effect on expression but not Wolbachia infection (F = 1.07, df = 1, p = 0.308). FADD expression levels were similarly reduced in Aag2wMel.tet (t = 6.46, df = 21, p < 0.0001) and Aag2wMel (t = 6.32, df = 19, p < 0.0001) after siRNA treatment (Fig. 2b). The knock down was also conferred to other genes downstream in the Imd pathway (Fig. S3). The achieved reduction of FADD expression in both cell lines relative to scrambled controls was ~2.3-fold.

Figure 2. Knockdown of antibacterial pathways.

Cell knockdown in Wolbachia-infected or tetracycline-treated Aag2 for (a) MyD88 (Toll) and (b) FADD (Imd). Gene expression was normalized to A. aegypti housekeeping gene rpS17. Graphs (c,d) correspond to DENV loads after cells were challenged with DENV-2 and collected at 5dpi. All graphs show medians with interquartile ranges (n = 12 per treatment). Black columns depict scrambled controls. Significance is based on post-hoc comparisons following ANOVAs on logarithmic transformed data. ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

After 18 h of targeted gene knockdown, infection with a DENV-2 strain was performed and cells were then collected at 5 days post infection (dpi). After Toll modulation, there was a significant effect of both the siRNA treatment (F = 75.66, df = 1, p < 0.0001) and Wolbachia infection (F = 1606.62, df = 1, p < 0.0001) on DENV load (Fig. 2c). The results show that the siRNA treatment leads to increases in DENV loads and Wolbachia infection leads to reductions in DENV load. There was also a slight significant interaction between Wolbachia status and siRNA treatment on DENV load (F = 5.1, df = 1, p = 0.03) as the magnitude of impact on DENV load was greater in Aag2wMel than in Aag2wMel.tet. These represent only 3.0 and 7.4% increase in the DENV load relative to scrambled controls for Wolbachia-free and Wolbachia-infected, respectively. It is unclear whether these differences are large enough to be biologically meaningful. When challenging FADD-knocked down cells (Fig. 2d), DENV loads were affected by Wolbachia infection status (F = 360.25, df = 1, p < 0.0001) as expected. There was however no effect of siRNA treatment (F = 1.69, df = 1, p = 0.873).

Our results point to Toll having an important role in A. aegypti’s immunity against DENV, but the pathway is not essential to explain the protective phenotype conferred by Wolbachia, as reported previously40 in Drosophila. We also do not see evidence of Imd pathway involvement in DENV protection, since inactivation of the pathway does not lead to an increase in DENV loads and Wolbachia infection does not affect its expression.

JAK/STAT

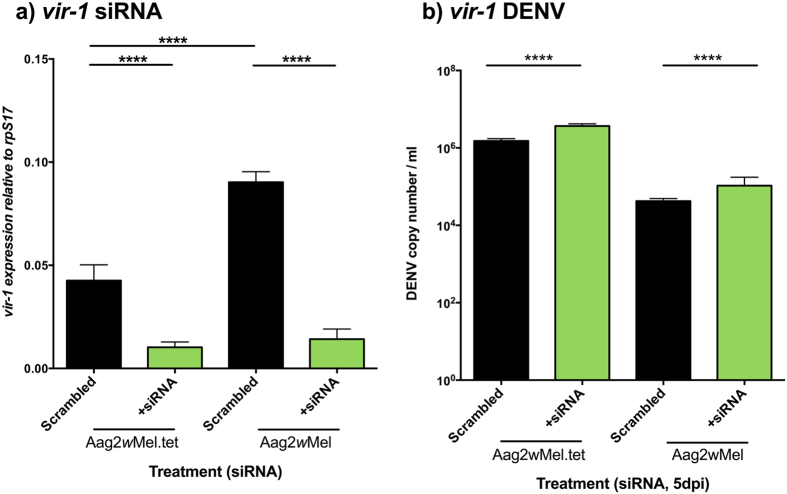

Both Wolbachia infection (F = 80.31, df = 1, p < 0.0001) and siRNA treatment (F = 355.13, df = 1, p < 0.0001) had significant effects on vir-1 expression (Fig 3a). A direct comparison of the expression levels in the scrambled treatment across lines revealed Wolbachia-associated increases in expression of vir-1 (t = 8.63, df = 19, p < 0.0001). The siRNA treatment produced a significant decrease in expression of vir-1 for both Aag2wMel.tet (t = 15.26, df = 20, p < 0.0001) and Aag2wMel (t = 12.15, df = 20, p < 0.0001). In comparison, relative to scrambled controls, the magnitude of the reduction in vir-1 expression was roughly 4.2-fold in the Aag2wMel.tet and 6-fold in Aag2wMel. We then tested if DENV levels were affected by the siRNA treatment and the Wolbachia infection status (Fig. 3b). There was a significant effect of the siRNA treatment (F = 18.88, df = 1, p < 0.0001) and of the Wolbachia infection (F = 337.75, df = 1, p < 0.0001). According to the results, the siRNA treatment increases DENV loads, whereas the presence of Wolbachia leads to a reduction in DENV, as expected. These represent only 5.8 and 7.9% increases in the DENV load relative to scrambled controls for Wolbachia-free and Wolbachia-infected, respectively. Importantly, the reduction of vir-1 expression in Aag2wMel does not lead to a recovery of DENV toward loads seen in Wolbachia uninfected untreated cells.

Figure 3. Knockdown of the JAK/STAT pathway.

(a) vir-1 gene (JAK/STAT) knockdown in Wolbachia-infected or tetracycline treated Aag2 cells. Gene expression was normalized to A. aegypti housekeeping gene rpS17. (b) DENV loads after knock down and challenge with DENV-2. Graphs show medians with interquartile ranges (n = 12 per treatment). Black columns depict scrambled controls. Significance is based on post-hoc comparisons following ANOVAs on logarithmic transformed data. ****p < 0.0001.

RNAi (Exogenous siRNA pathway)

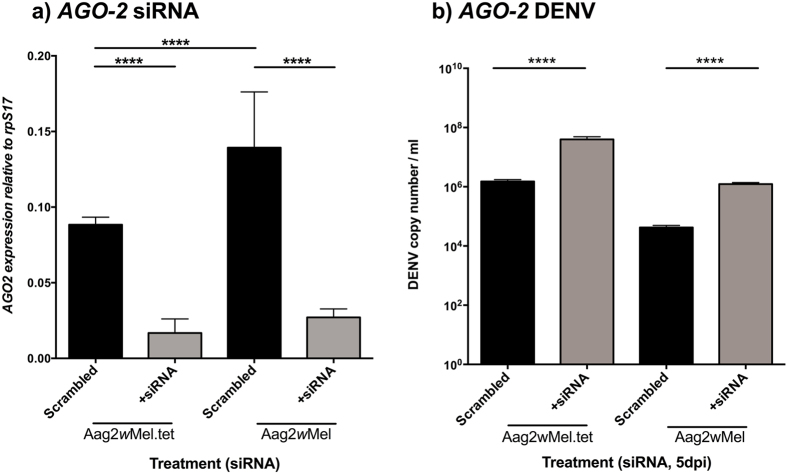

Both Wolbachia infection (F = 33.88, df = 1, p < 0.0001) and siRNA treatment (F = 264.75, df = 1, p < 0.0001) had significant effects on AGO2 expression (Fig. 4a). A direct comparison of the expression levels in the scrambled treatment across lines revealed Wolbachia-associated increases in expression of AGO2 (t = 6.29, df = 19, p < 0.0001). Targeted siRNA caused a decrease in AGO2 expression levels on both Aag2wMel.tet (t = 11.68, df = 19, p = 0.0033) and wMel-infected (t = 14.62, df = 19, p < 0.0001) lines. In comparison, relative to scrambled controls, the magnitude of the reduction in AGO2 expression was roughly 4.2-fold in the Aag2wMel.tet and 5.3-fold in Aag2wMel. When testing for effects on DENV loads after gene knockdown (Fig. 4b), both the effects of siRNA treatment (F = 1506, df = 1, p < 0.0001) and Wolbachia infection (F = 1667, df = 1, p < 0.0001) were significant. Similar to other genes tested, siRNA treatment caused DENV loads to increase whereas Wolbachia infection limited DENV replication. These increases in DENV load are on the order of 18.0 and 24.0% relative to scrambled controls for Wolbachia-free and Wolbachia-infected, respectively. These higher fold changes than previous genes demonstrate the importance in general of AGO2 for DENV control. The differential between the two lines (6%) represents the extra increase in DENV load that is due to Wolbachia via RNAi interactions.

Figure 4. Knockdown of RNAi.

(a) AGO2 gene (RNAi) knockdown in Wolbachia-infected or tetracycline treated Aag2 cells. Gene expression was normalized to A. aegypti housekeeping gene rpS17. (b) DENV loads after knock down and challenge with DENV-2. Graphs show medians with interquartile ranges (n = 12 per treatment). Black columns depict scrambled controls. Significance is based on post-hoc comparisons following ANOVAs on logarithmic transformed data. ****p < 0.0001.

Our results suggest that the exogenous siRNA pathway of those examined in the humoral response is the main controller of DENV replication in Aedes aegypti. When comparing specific antiviral pathways, the suppression of JAK/STAT through knockdown of vir-1 doesn’t affect DENV loads as much as inactivation of the exogenous siRNA pathway through knockdown of AGO2. The presence of Wolbachia increases basal AGO2 gene levels, which have been proven crucial for DENV control. We hypothesize that Wolbachia-mediated blocking of DENV is in part utilizing the exogenous siRNA pathway through up-regulation of its components to control DENV replication. This effect however explains less than 10% of Wolbachia’s ability to limit DENV.

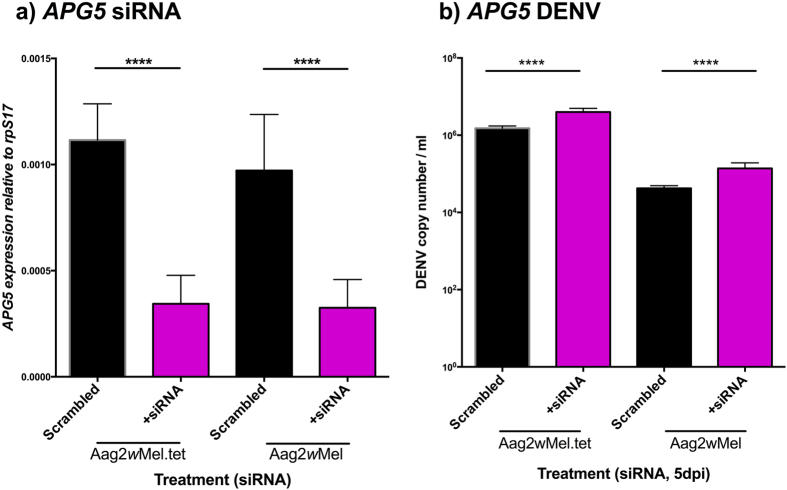

Autophagy

There was a significant effect of siRNA treatment (F = 132.18, df = 1, p < 0.0001) but not Wolbachia infection (F = 0.60, df = 1, p = 0.44) on APG5 expression (Fig. 5a). Successful knockdown of APG5 was achieved in Aag2wMel.tet (t = 8.14, df = 21, p < 0.0001) and Aag2wMel (t = 8.61, df = 18, p < 0.0001), reducing APG5 levels ~2.8-fold in both cell lines compared to scrambled control. A direct comparison of the expression levels in the scrambled treatment across lines also revealed no effect of Wolbachia infection on expression of APG5 (t = 0.96, df = 19, p < 0.34). There was a significant effect of siRNA treatment (F = 142.55, df = 1, p < 0.0001) and Wolbachia status (F = 1365, df = 1, p = 2.75e−7) on DENV load (Fig. 5b). Our results show that siRNA treatment leads to an increase in DENV load and Wolbachia presence reduces DENV. In comparison, relative to scrambled controls, the magnitude of the reduction in APG5 expression was roughly 6.3-fold in the Aag2wMel.tet and 10.0-fold in Aag2wMel.

Figure 5. Knockdown of autophagy.

(a) APG5 gene (autophagy) knockdown in Wolbachia-infected or tetracycline treated Aag2 cells. Gene expression was normalized to A. aegypti housekeeping gene rpS17. (b) DENV loads after knock down and challenge with DENV-2. Graphs show medians with interquartile ranges (n = 12 per treatment). Black columns depict scrambled controls. Significance is based on post-hoc comparisons following ANOVAs on logarithmic transformed data. ****p < 0.0001.

Even though DENV loads are increased with the suppression of APG5, the presence of Wolbachia does not modulate APG5 levels and the lines respond similarly to siRNA treatment. Altogether, it allows us to conclude that Wolbachia-based protection is not reliant on autophagy. This non-modulation of its expression levels indicates that autophagy is acting independently of the presence of a Wolbachia infection, but is probably an important factor in the A. aegypti general immune response against dengue virus.

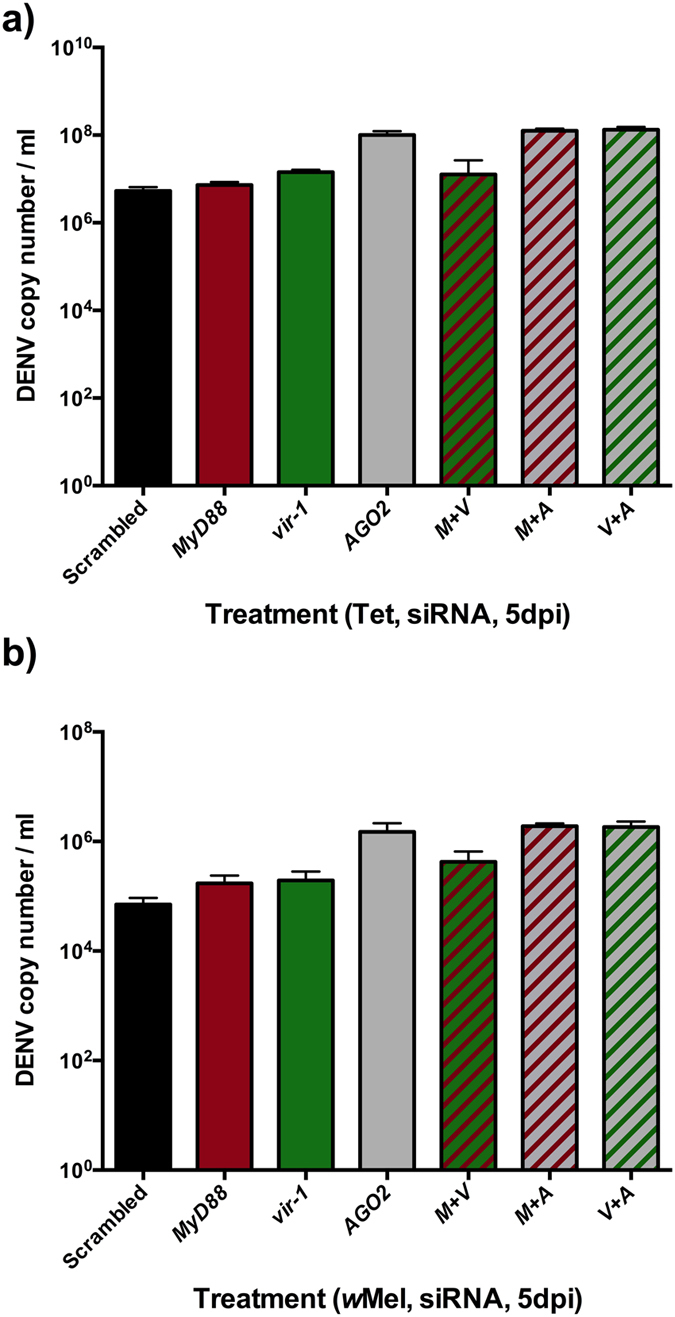

Stacking of Toll, JAK/STAT and RNAi

Sequential delivery of siRNAs for individual genes followed by AGO2 was necessary to test combined effects of pathways, as the efficacy of the siRNA treatment itself relies on a functional RNAi response. We first determined whether the knockdown of each individual gene was affected by the presence of the second siRNA. In all cases, save vir-1 in Aag2wMel only, the knockdown for each gene was the same between the single gene and stacked approach (Fig. S4), indicating a lack of interference or overlap between siRNAs. As previously reported, we found a Wolbachia-mediated up-regulation for three genes belonging to three different innate immune pathways. The genes were MyD88 (Toll; t = 3.461, df = 22, p = 0.0022), vir-1 (JAK/STAT; t = 4.257, df = 22, p = 0.0003) and AGO2 (exogenous siRNA; t = 4.495, df = 22, p = 0.0002).

Also shown previously in the single gene siRNA assays, the greatest increase in DENV load was for AGO2-treated samples (Fig. 6) for both Wolbachia-free (t = 28.04, df = 22, p < 0.0001) and infected line (t = 13.98, df = 21, p < 0.0001). In each case the control comparisons of single gene siRNA treatments versus the scrambled controls recapitulated the findings in the single gene assays. There was no effect of sequential treatment of siRNAs for vir-1 and MyD88 together compared to vir-1 alone on DENV load (Fig. 6, Table 1). In contrast, the stacking of MyD88 and vir-1 siRNAs each with AGO2 produced greater DENV loads than for AGO2 alone, demonstrating the contributory role of these pathways in DENV control. A marginally significant interaction for both of these comparisons AGO2 resulted from the slightly larger effect of siRNA treatment in Wolbachia infected cells compared to Wolbachia-free. The results of the stacking assays demonstrate the greater importance of AGO2 than MyD88 and vir-1 in DENV control but also in Wolbachia-mediated blocking. The contributions from the latter two pathways, while small, are additive.

Figure 6. Knockdown of stacked MyD88, vir-1 and AGO-2.

DENV load in response to single gene (solid bars) and stacked gene knockdowns (hatched bars) for (a) Aag2wMel.tet and (b) Aag2wMel. Black columns depict scrambled controls. Graphs show medians with interquartile ranges (n = 12 per treatment). Statistical significance reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Analysis of Variance table investigating single gene siRNA vs scrambled control and sequential treatment siRNA versus single gene treatments on DENV for Wolbachia-infected and Wolbachia-free lines.

| Comparison | Factors | F value | df | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scrambled vs MyD88 | siRNA treatment | 12.31 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Wolbachia (+/−) | 526.62 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| siRNA*Wolbachia | 9.46 | 1 | 0.004 | |

| Scrambled vs vir-1 | siRNA treatment | 97.82 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Wolbachia (+/−) | 467.72 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| siRNA*Wolbachia | 91.26 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| Scrambled vs AGO2 | siRNA treatment | 154.73 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Wolbachia (+/−) | 180.91 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| siRNA*Wolbachia | 145.59 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| vir-1 vs MyD88 + vir-1 | siRNA treatment | 0.898 | 1 | 0.35 |

| Wolbachia (+/−) | 113.28 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| siRNA*Wolbachia | 0.527 | 1 | 0.47 | |

| AGO2 vs AGO2 + MyD88 | siRNA treatment | 4.84 | 1 | 0.033 |

| Wolbachia (+/−) | 478.75 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| siRNA*Wolbachia | 4.28 | 1 | 0.045 | |

| AGO2 vs AGO2 + vir1 | siRNA treatment | 7.12 | 1 | 0.011 |

| Wolbachia (+/−) | 353.1 | 1 | <0.001 | |

| siRNA*Wolbachia | 6.72 | 1 | 0.013 |

Discussion

In this study we aimed to determine if any of the major innate immunity pathways in mosquitoes plays a role in Wolbachia-mediated DENV blocking. Using siRNA against single and pairs of genes, we reduced the transcription of key genes representing each of 5 immunity pathways in mosquito cells and assessed the impact of gene knockdown on DENV load. By comparing the responses of Wolbachia-infected to Wolbachia-free cells, we were able to specifically determine which genes were involved not only with anti-DENV responses, but contributing specifically to Wolbachia-mediated effects. The Toll, JAK/STAT and RNAi pathways all demonstrated increased basal expression in response to Wolbachia infection. When expression of the RNAi pathway was reduced, however, DENV loads in Wolbachia-infected cells rebounded, suggesting that Wolbachia-mediated blocking was in part reliant on the action of RNAi. The magnitude of this effect was small however, explaining less than 10% of the total DENV load. The differential involvement of genes in DENV control across the two lines was also seen for Toll and JAK/STAT, with greater DENV load increases seen in the Aag2wMel cell line compared to the tetracycline-treated line. These additional pathways therefore provide a small but significant contribution to the blocking conferred by RNAi. The additive nature of these gene contributions was further confirmed with the stacking assays.

In insects, RNAi plays a key role in antiviral defense. We focused on components of the exogenous siRNA pathway, whose primary function is the cleavage of dsRNA53. Briefly, exogenous dsRNA molecules are recognized and cleaved into smaller fragments (siRNAs) by a dsRNA-specific RNAse (Dicer). Then, siRNAs destroy their complementary mRNA targets by binding and guiding the complex to the argonaute protein that carries out endoribonucleic cleavage54. Because the silencing activity of siRNAs is responsive to the particular agent infecting the cell at any one time, it has broad efficacy against diverse viruses. Even though DENV is a (+) ssRNA virus, detectable amounts of dsRNA are created as replicative intermediates, similar to other flaviviruses55. Several studies have demonstrated the involvement of RNAi responses in regulating arboviruses including chikungunya, DENV, yellow fever or o’nyong-nyong inside the vector46,47,56,57.

Interestingly, in Drosophila, RNAi is not essential to achieve Wolbachia-mediated blocking from Drosophila C Virus48 and nor is it needed for control of Semliki Forest Virus in Drosophila cells infected with Wolbachia43. The fly and the mosquito may differ, however, with clear evidence of a much stronger and more far reaching immune response to Wolbachia in that latter42,58. Studies across a range of insect species suggest that older and more established Wolbachia:host associations may have lower Wolbachia densities, contracted tissue distributions and fewer effects on the immune response59,60,61,62. That Wolbachia may be causing a greater reaction in the recently infected A. aegypti is in keeping with co-evolutionary theories for novel host:pathogen pairings63. Additionally, mosquitoes/mosquito cells themselves may have histories of adaptation to native viruses that are not seen when non-native hosts like Drosophila are infected.

JAK/STAT has also been proposed as a major pathway involved in antiviral protection28,32. Our data supports previous studies suggesting that RNAi is more important for DENV control than JAK/STAT46. This difference between the two main antiviral pathways may stem from their mode-of-action. RNAi pathways are triggered by intracellular exogenous dsRNA64 whereas the activation of JAK/STAT is dependent on the binding of secreted ligands following pathogen recognition36. JAK/STAT’s antiviral mode of action remains unknown, though it is thought to be complex and versatile65. Moreover, DENV also suppress many signaling pathways. For example, the viral protein NS4B causes inhibition of the IFN pathway (JAK/STAT is involved in mammal type I interferon signaling66) by preventing STAT1 phosphorylation and activation, as well as its transport to the nucleus67. Similarly, NS5 has been shown to inhibit human STAT2 phosphorylation68. In mosquitoes, inhibition of immune signaling pathways Toll, Imd and JAK/STAT has been shown in the DENV-related Semliki Forest Virus69.

It is unclear how Wolbachia may be modulating the expression of either the RNAi or JAK/STAT pathways. Because RNAi acts intracellularly, there may be greater opportunities for the symbiont to manipulate its expression than for pathways like JAK/STAT. However, while cross talk has been demonstrated between JAK/STAT and Toll70, such interactions have not yet been shown between RNAi and other pathways that may respond directly to bacterial effectors. A previous study has shown that Wolbachia has the capacity to affect intracellular localization of AGO-1, a member of the miRNA pathway within RNAi71. It is not clear how this change is mediated, but it has capacity to affect the host’s immune response to pathogens.

Several aspects of the study’s design may limit the scope of its interpretation. First, as with any siRNA approaches, the ability to detect phenotypic effects is dependent on the strength of silencing. In almost all cases transcription was reduced by ~75% but we cannot rule out that additional effects might have emerged if we had reduced the gene expression further. Next, we have utilized the standard approach of creating a Wolbachia-free line by tetracycline treatment. Although few passages were allowed for treatment with antibiotics and for recovery, it is possible that some genetic drift occurred between the treatment and control lines. Regardless, the comparisons via a scrambled control intermediate should mitigate such issues. Creation of a newly Wolbachia-infected line where the original recipient line serves as the wildtype is also likely to lead to drift given the number of reinfection events and also selection that must commonly be employed to get a highly infected cell line72. Last, the approach taken here is highly reductionist. Blocking in adult mosquitoes is likely to be more complicated given the diversity of cell and tissue types and their potential to vary with respect to immune activity73. There is also likely, yet to be discovered, avenues of cross talk between immune pathways. More generally, these are complex interactions involving three organisms and their genomes. While the results can speak directly to the involvement of immune priming, our ability to estimate its proportional involvement relative to other mechanisms is limited.

Wolbachia is being released in a number of sites throughout the tropics as a possible biocontrol agent against viruses vectored by A. aegypti, including DENV and Zika15,74. Understanding mechanistically how Wolbachia restricts pathogen replication is key for assessing the long-term evolutionary stability of pathogen blocking in vector populations. Our findings show that increased expression of a gene in the mosquito’s antiviral response confers a small amount of DENV blocking in cells. Given the breadth of involvement of RNAi in protection against a range of arboviruses, this is likely to be true for Zika and other viruses vectored by A. aegypti. The concern, if blocking were heavily reliant on this immune reaction and not other factors, is the plasticity of gene expression as well as its capacity to evolve in response to pathogens75. In the field, mosquitoes may evolve tolerance to Wolbachia and limit the need to mount a costly immune response to the symbiont76. The vector may also evolve resistance, limiting Wolbachia densities or tissue distributions, as tends to be seen in native hosts such as Drosophila42,61,62,73,77. Field release populations of A. aegypti are being monitored to assess the stability of blocking and strategies are being developed for dealing with emerging resistance78. This study suggests at least that the risk reduced blocking efficacy due to a rapidly evolving immune response is low.

Materials and Methods

Cell line maintenance

The wMel strain was transinfected from D. melanogaster into the immune-competent A. aegypti cell line Aag279,80 using the shell vial technique, as previously performed for other mosquito cell lines72,81. The Aag2wMel cell line was serially passaged and checked for Wolbachia infection using quantitative PCR (qPCR)18 and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) against Wolbachia-specific 16S rRNA probe82. The control wMel uninfected line (Aag2wMel.tet) was obtained after three successive passages in the presence of tetracycline treatment at 10 mg/ml. The complete absence of Wolbachia was also confirmed using FISH and qPCR. Both cell types were routinely passaged in filtered complete media: a 1:1 mixture of Schneider’s media (Life Technologies) and Mitsuhashi-Maramorosch (MM), supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS (Life Technologies) and 1% Penicillin/Streptomycin (Life Technologies). Cells were reared in an incubator at 25 °C.

Virus

Dengue virus serotype-2 strain (ET-300; GenBank: EF440433.1) was isolated from a patient in East Timor-Leste in 2000 and passaged in C6/36 cells prior to experimental use. C6/36 cells were continuously kept in RPMI 1640 media (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS, Life Technologies), 1% Glutamax (Life Technologies), and 25 mM HEPES buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Cells were kept in a non-humidified incubator at 25 °C for optimal growth. Cells were allowed to grow to an 80% confluent monolayer prior to virus inoculation for 2 h and then maintained in 2% FBS media. Virus was collected at 7 days post-infection by harvesting the cell culture supernatant and centrifuged at max speed for 15′ at 4 °C. Virus was aliquoted and stored at −80 °C until use. Viral stocks were titrated using plaque assays and dengue copies quantified via qPCR. ET300 viral stocks were diluted in serum-free RPMI media to a concentration of 4 × 105 plaque forming units per milliliter before experimental use.

Wolbachia density

Wolbachia densities were measured in Aag2wMel after every passage and Aag2wMel.tet lines were assessed in parallel to confirm their uninfected status. We also assessed the effect of siRNA treatment on Wolbachia densities. Taqman® multiplex qPCR was performed to detect the wMel strain levels using primers for the Wolbachia WD0513 gene83 relative to the mosquito housekeeping mosquito gene rpS17 84 in a LightCycler480 instrument (Roche Applied Science, Switzerland). The primers used are listed in Table 2. Each multiplexed qPCR was run in triplicate and consisted of a 2x LightCycler480 Probes Master reaction mix, 10 μM rpS17 and wMel-IS5 primers, probes and 1.5 μl of DNA template in a total volume of 10 μl, as stated in the manufacturer’s protocol. Ratios of wMel-IS5 to rpS17 were obtained following the ∆∆Ct method85.

Table 2. Candidate genes and associated primers for each pathway.

| Gene ID | Pathway | Aedes gene name | Direction | Sequence (5′-3′) | Tm | Gene function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAEL017251 | RNAi | argonaute-2 | Fw | ACAACAGCAACAATCCCAGA | 60 | Catalytic compound of RISC, mRNA cleavage |

| Rv | GTGGACGTTGATCTTGTTGG | 60 | ||||

| AAEL002286 | Autophagy | APG5 | Fw | CCAGGACTTGTTGGAGGACT | 56 | Autophagosome elongation |

| Rv | GTCCGGATAGCTGAGGTGTT | 56 | ||||

| AAEL000627 | Toll | cecropin-A | Fw | CCATGGCTGTTCTTCTCCTGA | 60 | Antimicrobial peptide |

| Rv | GGCGGCATTGAAAACTCGTT | 60 | ||||

| AAEL004833 | Imd | diptericin-A | Fw | CCAATTCAGGAAGTGGAACC | 56 | Antimicrobial peptide |

| Rv | TGTTGATGGGTAGCTCCAAA | 56 | ||||

| AAEL014148 | Imd | dredd | Fw | GTGGCTGTTATGCGAGAAGA | 60 | Initiatior caspase, cleavage of REL2 |

| Rv | AGCGTAGTTCTGCCTGAGGT | 60 | ||||

| AAEL001932 | Imd | FADD | Fw | GGGACCGTCGAACACTTCTT | 60 | Imd signal transducer |

| Rv | CACTCAGCTGCATTAACCGC | 60 | ||||

| AAEL007768 | Toll | MyD88 | Fw | GGACTACAAGCGCTCGAACA | 60 | TOLL signaling cascade starter |

| Rv | CTGGTTTGGTTTGCGTTCGA | 60 | ||||

| AAEL006571 | Toll | PELLE | Fw | ACAACCGACGAAAACTCCGA | 56 | Signaling molecule - Kinase |

| Rv | GCGAAGTTCTTCCCCACTGA | 56 | ||||

| AAEL000718 | JAK/STAT | vir-1 | Fw | GCCAAAGTCCGGTATTCTTC | 60 | Antiviral effector |

| Rv | TTCACGAGATCGTCAAGGTAA | 60 | ||||

| AAEL004175 | — | rpS17 | Fw | TCCGTGGTATCTCCATCAAGCT | 60 | Ribosomal small subunit assembly |

| Rv | CACTTCCGGCACGTAGTTGTC | 60 | ||||

| AE017196 | — | WD0513 | Fw | GTATCCAACAGATCTAAGC | 60 | |

| Rv | ATAACCCTACTCATAGCTAG | 60 | ||||

| NC_001474.2 | — | DENV | Fw | AAGGACTAGAGGTTAGAGGAGACCC | 60 | |

| Rv | CGTTCTGTGCCTGGAATGATG | 60 | ||||

| Pr | HEX-AACAGCATATTGACGCTGGGAGAGACCAGA-BHQ1 |

Gene function from Flybase and Swiss-Prot.

siRNA transfection

Aag2wMel and Aag2wMel.tet cells were seeded the day before transfection in a flat bottom Greiner 96-well plate (Sigma-Aldrich) at a 70–80% confluence. The following day, three different treatments were applied to the cells in a serum-free environment: Mock transfected, Scrambled siRNA at 10 μM and gene of interest (GOI) siRNA at 10 μM. Custom siRNAs targeting A. aegypti immune genes were manufactured by Sigma-Aldrich. All siRNA treatments were performed with the addition of Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Sigma-Aldrich) reagent, and transfected altogether according to manufacturer’s protocol. The single gene assays (n = 6 replicate wells per treatment) were replicated a second time and pooled (n = 12). For stacking experiments, (n = 12 replicate wells per treatment) the second GOI siRNA was applied to the sample 18 h after the first siRNA treatment, performed as stated above.

RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Cell RNA was extracted from cells 18 to 36 h hours post transfection using the Nucleospin 96 RNA kit (Machery-Nagel, Germany), following modified manufacturer’s protocol. cDNA synthesis reactions were performed using SuperScript® III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen) and contained 12.5 μl of RNA template, 1 μl of random primers (RP, 125 ng/μl), 1 μl of deoxynucleotides (dNTPs, 2.5 mM), dithiothreitol (DTT), 5X buffer and enzyme as per kit instructions, in a total volume of 20 μl. Reactions were carried out in a C1000™Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) with the cycling regime: 65 °C for 5 min followed by 10 min at 25 °C, 50 min at 50 °C, 10 min at 75 °C.

Selection of candidate immunity genes

Candidate genes were selected for each pathway of interest that met the following criteria: they had to be required for the function of the pathway, be sufficiently transcribed and the ability to be knocked down efficiently in our cell model. Refer to Table 2 for chosen candidates and associated primer sequences with gene IDs and function. All primers were designed using the open-source Primer3 software86. For candidates involved upstream we confirmed that expression of downstream genes (Toll and Imd) was reduced after targeted knockdown to assure complete inactivation of the pathway.

Immunity gene quantitative PCR analysis

Gene expression was measured using SYBR® Green I Master (Roche) according to manufacturer’s protocol. All runs were performed in duplicate using a 10 times dilution of the cDNA. The temperature profile used is as follows: one cycle at 95 °C for 5 min followed by 45 amplification cycles of 95 °C for 10 sec, 60 °C for 10 sec and 72 °C for 10 sec, followed by a melting curve analysis after the last cycle. In all qPCR analyses, GOI were normalized to the housekeeping gene rpS17, run in parallel. GOI to housekeeping gene ratios were obtained for each biological sample using the aforementioned ∆∆Ct method85.

DENV infection and quantification

DENV infections were performed 18 h post-transfection with siRNA. Cells were washed with PBS before and after the virus inoculation at a DENV-2 multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.5. At this MOI DENV-blocking in wMel is most clearly seen as per pilot studies (data not shown). The viral inoculum was removed 2 h post-infection and cells were grown in complete media containing 2% FBS. DENV was quantified 5 days post-infection by collection of 20 μl supernatant and mixed 1:1 with 20 μl squash buffer (10 mM Tris base, 1 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaCl and 0.25 μl proteinase K). They were then incubated in a C1000™Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, California USA) at 56 °C for 5 min, then 98 °C for 5 min for the simultaneous isolation of RNA and DNA. The RNA/DNA was subsequently used for the absolute quantification of DENV-2 via qPCR using a standard curve, as described previously87.

One-step quantitative PCR was performed using TaqMan® Fast Virus 1-step Master Mix (Roche) in a total 10 μl, following manufacturer’s instructions.

The primer sequences used for the detection of DENV were as described previously87. The thermal profile was as stated previously for qPCR analysis, with the addition of 10 min incubation retrotranscription step at 50 °C followed by 20 sec at 95 °C for RT inactivation at the start of the run.

Data analysis

qPCR reactions were run in duplicate and samples that failed to amplify for at least one replicate were removed. Statistics were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics (v23) and R software (R Development Core Team (2008), Vienna, Austria). Gene expression ratios and dengue loads were both log transformed prior to analysis. Two-way ANOVAs were performed testing for the effects of Wolbachia infection (presence/absence), siRNA treatment (+/−) and replicate (1, 2) as factors on gene expression or DENV load. At no point was ‘replicate’ significant and so reported statistics focus only on main effects. Interactions are reported only when significant. Post hoc comparisons were employed multiple tests accounted for using a Bonferroni correction, leading to adjusted p-values of 0.025 and 0.017, when 2 or 3 comparisons were made, respectively. All DENV loads were reported on a log scale given the spread of values.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Terradas, G. et al. The RNAi pathway plays a small part in Wolbachia-mediated blocking of dengue virus in mosquito cells. Sci. Rep. 7, 43847; doi: 10.1038/srep43847 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Yi Dong for creating the Wolbachia-infected cell line. The research was supported by a National Health & Medical Research Council of Australia grant (APP1103804) to EAM.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions E.A.M., G.T. and D.A.J. designed the experiments. G.T. performed the experiments. G.T. and E.A.M. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- WHO. World Health Organization. Dengue and dengue haemorragic fever. Fact sheet No. 117 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D. Dengue and Dengue Hemorragic Fever. Clin microbiol rev 11, 480–496 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gubler D. J. Epidemic dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever as a public health, social and economic problem in the 21st century. Trends Microbiol 10, 100–103, doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(01)02288-0 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guzman M. G. et al. Dengue: a continuing global threat. Nat rev Microbiol 8, S7–16, doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2460 (2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt S. et al. The global distribution and burden of dengue. Nature 496, 504–507, doi: 10.1038/nature12060 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstead S. B. Dengue virus-mosquito interactions. Annu Rev Entomol 53, 273–291, doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093326 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilder-Smith A. et al. DengueTools: innovative tools and strategies for the surveillance and control of dengue. Glob Health Action 5, doi: 10.3402/gha.v5i0.17273 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings D. A. T. et al. Travelling waves in the occurrence of dengue haemorragic fever in Thailand. Nature 427, 344–347 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colon-Gonzalez F. J. F. C., Lake I. R. & Hunter P. R. The effects of weather and climate change on dengue. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7, e2503, doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002503 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabchareon A. et al. Protective efficacy of the recombinant, live-attenuated, CYD tetravalent dengue vaccine in Thai schoolchildren: a randomised, controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet 380, 1559–1567, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61428-7 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capeding M. R. et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of a novel tetravalent dengue vaccine in healthy children in Asia: a phase 3, randomised, observer-masked, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 384, 1358–1365, doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61060-6 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grange L. et al. Epidemiological risk factors associated with high global frequency of inapparent dengue virus infections. Front Immunol 5, 280, doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00280 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C., Ortiz K., Ansari A. & Gershwin M. E. The Zika outbreak of the 21st century. J Autoimmun 68, 1–13, doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2016.02.006 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tambo E., Chuisseu P. D., Ngogang J. Y. & Khater E. I. Deciphering emerging Zika and dengue viral epidemics: Implications for global maternal-child health burden. J Infect Public Health 9, 240–250, doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.02.005 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw E. A. & O’Neill S. L. Beyond insecticides: new thinking on an ancient problem. Nat Rev Microbiol 11, 181–193, doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2968 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlat S., Hurst G. D. D. & Merçot H. Evolutionary consequences of Wolbachia infections. Trends Genet 19, 217–223, doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(03)00024-6 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker T. J. P. H., Moreira L. A., Iturbe-Ormaetxe I., Frentiu F. D., McMeniman C. J., Leong Y. S., Dong Y., Axford J., Kriesner P., Lloyd A. L., Ritchie S. A., O’Neill S. L. & Hoffmann A. A. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature 476, 450–453, doi: 10.1038/nature10355 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann A. A. et al. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature 476, 454–457, doi: 10.1038/nature10356 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira L., Ferreira A. & Ashburner M. The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Biol 6, e2, doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000002 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L. M., Brownlie J. C., O’Neill S. L. & Johnson K. N. Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science 322, 702 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira L. A. et al. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell 139, 1268–1278, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambris Z., Cook P. E., Phuc H. K. & Sinkins S. P. Immune activation by life-shortening Wolbachia and reduced filarial competence in mosquitoes. Science 326, 134–136, doi: 10.1126/science.1177531 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caragata E. P. et al. Dietary cholesterol modulates pathogen blocking by Wolbachia. PLoS Path 9, e1003459, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003459 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain M., Frentiu F. D., Moreira L. A., O’Neill S. L. & Asgari S. Wolbachia uses host microRNAs to manipulate host gene expression and facilitate colonization of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108, 9250–9255 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bian G., Xu Y., Lu P., Xie Y. & Xi Z. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia induces resistance to dengue virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Path 6, e1000833, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000833 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rancès E., Ye Y. H., Woolfit M., McGraw E. A. & O’Neill S. L. The relative importance of innate immune priming in Wolbachia-mediated dengue interference. PLoS Path 8, e1002548, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002548 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B., Nicolas E., Michaut L., Reichhart J.-M. & Hoffmann J. A. The Dorsoventral Regulatory Gene Cassette spätzle/Toll/cactus Controls the Potent Antifungal Response in Drosophila Adults. Cell 86, 973–983 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dostert C. et al. The Jak-STAT signaling pathway is required but not sufficient for the antiviral response of Drosophila. Nat Immunol 6, 946–953, doi: 10.1038/ni1237 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C. L. et al. Aedes aegypti uses RNA interference in defense against Sindbis virus infection. BMC Microbiol 8, 47, doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-47 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avadhanula V., Weasner B. P., Hardy G. G., Kumar J. P. & Hardy R. W. A novel system for the launch of alphavirus RNA synthesis reveals a role for the Imd pathway in arthropod antiviral response. PLoS Path 5, e1000582, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000582 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper D. M., Chamberlain C. M. & Lowenberger C. Aedes FADD: a novel death domain-containing protein required for antibacterial immunity in the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 39, 47–54, doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2008.09.011 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Neto J. A., Sim S. & Dimopoulos G. An evolutionary conserved function of the JAK-STAT pathway in anti-dengue defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106, 17841–17846, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905006106 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamoto M. et al. Virus recognition by Toll-7 activates antiviral autophagy in Drosophila. Immunity 36, 658–667, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.003 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H., Kambris Z., Lemaitre B. & Hashimoto C. Two proteases defining a melanization cascade in the immune system of Drosophila. J Biol Chem 281, 28097–28104, doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601642200 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudzic J. P., Kondo S., Ueda R., Bergman C. M. & Lemaitre B. Drosophila innate immunity: regional and functional specialization of prophenoloxidases. BMC Biol 13, 81, doi: 10.1186/s12915-015-0193-6 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agaisse H. & Perrimon N. The roles of JAK/STAT signaling in Drosophila immune responses. Immunol rev 198, 72–82 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z., Ramirez J. L. & Dimopoulos G. The Aedes aegypti Toll Pathway Controls Dengue Virus Infection. PLoS Path 4, 1–12, doi: 10.1371/ (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim S. & Dimopoulos G. Dengue virus inhibits immune responses in Aedes aegypti cells. PloS One 5, e10678, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010678 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira A. G. et al. The Toll-dorsal pathway is required for resistance to viral oral infection in Drosophila. PLoS Path 10, e1004507, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004507 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rancès E. et al. The toll and Imd pathways are not required for Wolbachia-mediated dengue virus interference. J Virol 87, 11945–11949, doi: 10.1128/JVI.01522-13 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z., Gavotte L., Xie Y. & Dobson S. L. Genome-wide analysis of the interaction between the endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia and its Drosophila host. BMC Genomics 9, 1, doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-1 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y. H., Woolfit M., Rances E., O’Neill S. L. & McGraw E. A. Wolbachia-associated bacterial protection in the mosquito Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7, e2362, doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002362 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainey S. M. et al. Wolbachia Blocks viral genome replication early in infection without a transcriptional response by the endosymbiont or host small RNA pathways. PLoS path 12, e1005536, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005536 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradkar P. N., Trinidad L., Voysey R., Duchemin J.-B. & Walker P. J. Secreted Vago restricts West Nile virus infection in Culex mosquito cells by activating the Jak-STAT pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 18915–18920 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barillas-Mury C. V. Anopheles gambiae Ag-STAT, a new insect member of the STAT family, is activated in response to bacterial infection. EMBO J 18, 959–967 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Vargas I. et al. Dengue virus type 2 infections of Aedes aegypti are modulated by the mosquito’s RNA interference pathway. PLoS Path 5, e1000299, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000299 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane M. et al. Characterization of Aedes aegypti innate-immune pathways that limit Chikungunya virus replication. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 8, e2994, doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002994 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedges L. M., Yamada R., O’Neill S. L. & Johnson K. N. The small interfering RNA pathway is not essential for Wolbachia-mediated antiviral protection in Drosophila melanogaster. Appl Environ Microbiol 78, 6773–6776, doi: 10.1128/AEM.01650-12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser R. L. & Meola M. A. The native Wolbachia endosymbionts of Drosophila melanogaster and Culex quinquefasciatus increase host resistance to West Nile virus infection. PloS One 5, e11977, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011977 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelly S., Lukinova N., Bambina S., Berman A. & Cherry S. Autophagy is an essential component of Drosophila immunity against vesicular stomatitis virus. Immunity 30, 588–598, doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.009 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidyanathan R. & Scott T. W. Apoptosis in mosquito midgut epithelia associated with West Nile virus infection. Apoptosis 11, 1643–1651, doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-8783-y (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo C. B. et al. Differential expression of apoptosis related genes in selected strains of Aedes aegypti with different susceptibilities to dengue virus. PloS One 8, e61187, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061187 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C. D. Mosquito RNAi is the major innate immune pathway controlling arbovirus infection and transmission. Future Microbiol 6, 265–277, doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.11 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carthew R. W. & Sontheimer E. J. Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 136, 642–655, doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.035 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westaway E. G., Mackenzie J. M., Kenney M. T., Jones M. K. & Khromykh A. A. Ultrastructure of kunjin virus-infected cells: colocalization of NS1 and NS3 with double-stranded RNA, and of NS2B with NS3, in virus-induced membrane structures. J Virol 71, 6650–6661 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene K. M. et al. RNA interference acts as a natural antiviral response to O’nyong-nyong virus (Alphavirus; Togaviridae) infection of Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101, 17240–17245, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406983101 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacca C. C. et al. RNA interference inhibits yellow fever virus replication in vitro and in vivo. Virus Genes 38, 224–231, doi: 10.1007/s11262-009-0328-3 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong Z. S., Hedges L. M., Brownlie J. C. & Johnson K. N. Wolbachia-mediated antibacterial protection and immune gene regulation in Drosophila. PloS One 6, e25430, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025430 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobson S. L. et al. Wolbachia infections are distributed throughout insect somatic and germ line tissues. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 29, 153–160 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q. et al. Tissue distribution and prevalence of Wolbachia in tsetse flies, Glossina spp. Med Vet Entomol 14, 44–50 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veneti Z., Clark M. E., Karr T. L., Savakis C. & Bourtzis K. Heads or tails: host-parasite interactions in the Drosophila-Wolbachia system. Appl Environ Microbiol 70, 5366–5372, doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.9.5366-5372.2004 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W. J. & Riegler M. Evolutionary dynamics of wAu-like Wolbachia variants in neotropical Drosophila spp. Appl Environ Microbiol 72, 826–835, doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.1.826-835.2006 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siozios S., Sapountzis P., Ioannidis P. & Bourtzis K. Wolbachia symbiosis and insect immune response. Insect Sci 15, 89–100, doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7917.2008.00189.x (2008). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghildiyal M. & Zamore P. D. Small silencing RNAs: an expanding universe. Nat Rev Genet 10, 94–108, doi: 10.1038/nrg2504 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsolver M. B., Huang Z. & Hardy R. W. Insect antiviral innate immunity: pathways, effectors, and connections. J Mol Biol 425, 4921–4936, doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.10.006 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takaoka A. & Yanai H. Interferon signalling network in innate defence. Cell Microbiol 8, 907–922, doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00716.x (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz-Jordan J. L. et al. Inhibition of alpha/beta interferon signaling by the NS4B protein of flaviviruses. J Virol 79, 8004–8013, doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.13.8004-8013.2005 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzon M., Jones M., Davidson A., Chain B. & Jacobs M. Dengue virus NS5 inhibits interferon-alpha signaling by blocking signal transducer and activator of transcription 2 phosphorylation. J Infect Dis 200, 1261–1270, doi: 10.1086/605847 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragkoudis R. et al. Semliki Forest virus strongly reduces mosquito host defence signaling. Insect Mol Biol 17, 647–656, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2008.00834.x (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsolver M. B. & Hardy R. W. Making connections in insect innate immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 18639–18640, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216736109 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain M., O’Neill S. L. & Asgari S. Wolbachia interferes with the intracellular distribution of Argonaute 1 in the dengue vector Aedes aegypti by manipulating the host microRNAs. RNA Biol 10, 1868–1875, doi: 10.4161/rna.27392 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMeniman C. J. et al. Host adaptation of a Wolbachia strain after long-term serial passage in mosquito cell lines. Appl Environ Microbiol 74, 6963–6969, doi: 10.1128/AEM.01038-08 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne S. E., Iturbe-Ormaetxe I., Brownlie J. C., O’Neill S. L. & Johnson K. N. Antiviral protection and the importance of Wolbachia density and tissue tropism in Drosophila simulans. Appl Environ Microbiol 78, 6922–6929, doi: 10.1128/AEM.01727-12 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra H. L. et al. Wolbachia Blocks currently circulating zika virus isolates in brazilian aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Cell Host Microbe 19, 771–774, doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.021 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y. H., Chenoweth S. F. & McGraw E. A. Effective but costly, evolved mechanisms of defense against a virulent opportunistic pathogen in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Path 5, e1000385, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000385 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anbutsu H. & Fukatsu T. Evasion, suppression and tolerance of Drosophila innate immunity by a male-killing Spiroplasma endosymbiont. Insect Mol Biol 19, 481–488, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01008.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez J. et al. Symbionts commonly provide broad spectrum resistance to viruses in insects: a comparative analysis of Wolbachia strains. PLoS Paths 10, e1004369, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004369 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joubert D. A. et al. Establishment of a wolbachia superinfection in aedes aegypti mosquitoes as a potential approach for future resistance management. PLoS path 12, e1005434, doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005434 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peleg J. Growth of arboviruses in monolayers from subcultured mosquito embryo cells. Virology 35, 617–619 (1968). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fallon A. M. & Sun D. Exploration of mosquito immunity using cells in culture. Insect Biochem Mol Biol 31, 263–278 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voronin D., Tran-Van V., Potier P. & Mavingui P. Transinfection and growth discrepancy of Drosophila Wolbachia strain wMel in cell lines of the mosquito Aedes albopictus. J Appl Microbiol 108, 2133–2141, doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04621.x (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker T. et al. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature 476, 450–453, doi: 10.1038/nature10355 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amuzu H. E. & McGraw E. A. Wolbachia-based dengue virus inhibition is not tissue-specific in aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10, e0005145, doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005145 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook P. E. et al. The use of transcriptional profiles to predict adult mosquito age under field conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 18060–18065, doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604875103 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K. J. & Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408, doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Untergasser A. et al. Primer3–new capabilities and interfaces. Nucleic Acids Res 40, e115, doi: 10.1093/nar/gks596 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y. H. et al. Comparative susceptibility of mosquito populations in North Queensland, Australia to oral infection with dengue virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg 90, 422–430, doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.13-0186 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.