Abstract

Citizen science projects have a long history in ecological studies. The research usefulness of such projects is dependent on applying simple and standardized methods. Here, we conducted a citizen science project that involved more than 3500 Swedish high school students to examine the temperature difference between surface water and the overlying air (Tw-Ta) as a proxy for sensible heat flux (QH). If QH is directed upward, corresponding to positive Tw-Ta, it can enhance CO2 and CH4 emissions from inland waters, thereby contributing to increased greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. The students found mostly negative Tw-Ta across small ponds, lakes, streams/rivers and the sea shore (i.e. downward QH), with Tw-Ta becoming increasingly negative with increasing Ta. Further examination of Tw-Ta using high-frequency temperature data from inland waters across the globe confirmed that Tw-Ta is linearly related to Ta. Using the longest available high-frequency temperature time series from Lake Erken, Sweden, we found a rapid increase in the occasions of negative Tw-Ta with increasing annual mean Ta since 1989. From these results, we can expect that ongoing and projected global warming will result in increasingly negative Tw-Ta, thereby reducing CO2 and CH4 transfer velocities from inland waters into the atmosphere.

Research organizations and funding agencies are increasingly striving to include society in science, to justify the use of public funds for research and to raise societal awareness and scientific knowledge. In the best cases, citizen participation is a win-win situation where society becomes more informed and scientists secure valuable data1,2. To develop reliable citizen science projects is a challenge because they require simple and unambiguous descriptions and methods that are standardized and easy to apply3,4. Here, we used citizen science to better understand temporal and spatial variation in the potential transfer of the greenhouse gases carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) from inland waters to the atmosphere by engaging secondary school students to collect water and air temperature data from a diverse set of water bodies across a large geographical region.

Theory behind the citizen science project

The transfer of CO2 and CH4 from inland waters to the atmosphere is an important component of the global carbon cycle5. Recent estimates demonstrate that about 2.1 PgC yr−1 are emitted from inland waters to the atmosphere in the form of CO26, an amount comparable to CO2 uptake by oceans (~2.0 PgC yr−1)7. The emission estimates, however, are still uncertain because they are based on a simplified measure of the gas transfer velocity k where the sensible heat flux (QH) has been neglected6. Although QH is a relatively minor component of the total heat flux8,9, QH can substantially enhance k and thereby the total emission flux10,11,12,13,14. For example, measured and calculated CO2 emission flux from a lake can differ by up to 79% when QH is not considered in the calculation of the emission flux15.

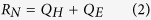

QH enhances k when it is directed upward, i.e. when heat is transferred from water to the air which occurs when water is warmer than the overlying air. Under these conditions the buoyancy flux is negative and the resulting turbulent mixing from heat loss is responsible for the majority of gas exchange14. Thus, the temperature difference between water and air (Tw-Ta) is an important measure because its sign regulates whether QH is directed upward, i.e. from water into the atmosphere, or downward, i.e. from the atmosphere into water according to10:

|

where ρa is the density of air, Cp is the specific heat capacity of air at constant pressure (1005 J kg−1 K−1), CH is the turbulent transfer coefficient for sensible heat, and Ua is the near-surface wind speed. Although turbulence from heat loss is known to be the primary driver of gas flux in many lakes around the world16,17, the distribution, sign, and magnitude of Tw-Ta are still unknown for most of our inland waters. Thus, the precision of present greenhouse gas emission estimates from inland waters remains unclear.

The distribution, sign, and magnitude of Tw-Ta vary across water bodies and over time. We aimed to fill the present knowledge gap on spatial Tw-Ta variation using data from citizen scientists. To fill the present knowledge gap on temporal Tw-Ta variability, we used high-frequency temperature data from 14 lakes distributed around the globe. In addition to the assessment of Tw-Ta spatial and temporal variability, we also set out to find a relationship between Tw-Ta and the color of water. Water color affects the attenuation of solar radiation18,19 which most likely results in changes to Tw-Ta. The possible effects of water color on Tw-Ta are highly relevant because waters in the Northern Hemisphere are becoming browner20,21. As a final step, we analyzed the inter-annual development of Tw-Ta using the longest available time series of high-frequency water and air temperature measurements from 1989 to 2015.

Methods

Design of the citizen science project

For the citizen science project, we chose high school students between 14 and 16 years of age because these students already have a basic knowledge in natural sciences and soon have to decide if they would like to continue studying this discipline. We introduced the citizen science project via webpages, Facebook and other social media, and produced a short video (http://www.teknat.uu.se/bruntvatten/). Originally, we intended to involve 100 classes across Sweden but due to unexpected high interest already during the first hours of registration, we extended participation to 240 classes. We sent packages to all the schools, each of them containing field protocols, a thermometer, sampling tubes, and a detailed experimental description for teachers. In addition, the pack contained a detailed questionnaire that students could choose to fill out, which had a direct connection to the teaching goals of grades 7 to 9 in natural sciences.

We asked the teachers and students to choose a water body near their school and to measure surface water temperature at 0.5 m water depth and air temperature at 1.5 m above the sampling site. At each sampling site, the students were asked to fill in a protocol with weather observations, their temperature measurements, pH measurements, their exact sampling location and an estimation of water color using the Forel-Ule color index scale22. The students were also asked to take a photograph of their water body and to fill 50-ml sampling tubes with water from 0.5 m water depth from each measuring site, which they could then send to the limnological laboratory at Uppsala University. The water samples were used as a control for the students’ water color estimates. We chose 10 of the most brownish, 10 of intermediate brownish, and 10 of the most transparent water samples, as indicated by photographic records taken at each site by the students, and measured the absorbance at 420 nm in a 1 cm cuvette (Abs420nm/1cm) as a proxy of water color.

The project began in May 2016 when school teachers registered. The actual sampling took place between August 15 and September 30 in 2016. At the beginning of September, school classes were invited to have a 15-minute conversation with the project leader via Skype. Over the course of the project we constantly provided feedback to teachers and students, and at the end of the project we sent out a project evaluation sheet to all the class teachers.

High-frequency temperature measurements

We combined the temperature data from the citizen science project with high-frequency temperature measurements in inland waters at about 0.5 m water depth and the overlying air at about 1.5 m above the water in 14 diverse lakes from four continents and ten countries (Table 1). The high-frequency temperature data are available via the GLEON network at http://www.gleon.org. We included complete time series of high-frequency temperature data during the open water season from May to October. All lakes had at least one year of complete data, except for the Brazilian floodplain lake for which only 14 days of data were available. The longest high-frequency time series with day and night and under ice water temperature measurements was available from Lake Erken, Sweden (Table 1). This time series was used to analyze inter-annual variation of Tw-Ta from 1989 to 2015. Four years, i.e. 1993, 1994, 1996, and 2003, were not considered in this study since they lacked more than 2900 out of 8760 measurements (or 8784 during a leap year) due to instrumentation failure.

Table 1. Information on high-frequency temperature data automatically measured in lakes (at a water depth of ~0.5 m) and the overlying air (~1.5 m above the water) in 14 diverse lakes. The lakes are sorted from North to South.

| Lake Country | Location of measuring site (Latitude and Longitude) | Lake surface area | Mean lake depth | Frequency of recorded measurements | Years of measurements considered in this study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Erken Sweden | 59°50’20”N, 18°37’46”E | 24.2 km2 | 9 m | Every 60 minutes | 1989–2015 |

| Peipsi Estonia/Russia | 58°14’15”N, 27°28’28”E | 3555 km2 | 7.1 m | Air temperature every 60 minutes, water temperature at 8 AM and 8 PM (local time) | 2008–2015 |

| Feeagh Ireland | 53°55’12”N, 9°34’12”W | 4.0 km2 | 14.5 m | Once daily | 2013 |

| Stechlin Germany | 53°09’06”N, 13°10’34”E | 4.3 km2 | 22.3 m | Every 60 minutes | 2012– 2014 |

| Bala UK | 52°53’27”N, 3°37’12”W | 4.1 km2 | 24 m | Every 60 minutes | 2011 |

| Buffalo Pound Canada | 50°35'09”N, 105°23'02”W | 24.4 km2 | 3.8 m | Every10 minutes | 2015 |

| Lake 239 Canada | 49°39'48”N, 93°43'24”W | 0.54 km2 | 11.0 m | Every 10 minutes | 2012 |

| Rimov Reservoir Czechia | 48°50'56”N, 14°29'28”E | 1.8 km2 | 15 m | Every 10 minutes ; | 2015 |

| Douglas US | 45°33'54”N, 84°40'20”W | 13.7 km2 | 8 m | Every 10 minutes | 2011–2015 |

| Harp Canada | 45°22'48”N, 79°08'09”W | 0.7 km2 | 13.3 m | Every 10 minutes | 2013 |

| Shelburne Pond US | 44°23'38”N, 73°09'46”W | 1.8 km2 | 3.4 m | Every 15 minutes | 2015 |

| Emerald US | 36°35’49” N, 118°40’29”W | 0.03 km2 | 6.0 m | Every 60 minutes | 2011 |

| Kivu Democratic Republic of the Congo/Rwanda* | 1°43’30”S, 29°14’15”E | 2700 km2 | 240 m | Every 30 minutes | 2013 |

| Curuai floodplain lake (Amazon) Brazil | 2°04’12”S 55°03’58”W | 2250 km2 at high water | 6 m at high water | 30 seconds for water temperature, every 5 minutes for air temperature | 2014 (14 days of data) |

*At Kivu Water temperature was monitored ~2 km southwest of the air temperature measurement site. Because the basin is spatially very homogeneous9, we considered this approach to provide reliable results.

Statistics

All statistical tests were run in JMP, version 12.0. Due to non-normally distributed data, tested by a Shapiro-Wilk test, we used the non-parametric Wilcoxon test for group comparisons and the non-parametric Mann-Kendall test for trend analyses. The Mann-Kendall test23 tests if long-term changes of a variable are significant (p < 0.05). For the trend analyses we used yearly median values. We also calculated the Theil-slope to get a quantitative measure of changes over time.

Results and Discussion

Spatial variation in Tw-Ta and the influence of water color – data from the citizen scientists

We received protocols and samples back from 80% (192) of the 240 registered classes. A number of teachers were unable to complete the project because they had changed jobs or were on parental or sick leave. In total, we received 1355 paired water (Tw) and air (Ta) temperatures. The measurements were recorded in 11 small ponds, 49 lakes, 22 streams/rivers and at two Baltic Sea shore sampling sites between August 15 and September 30. Most sampling sites were located in Sweden’s most populated areas such as Stockholm, Malmö and Gothenburg but the distribution of sites was surprisingly extensive across Sweden, spanning 56 to 65°N (Fig. 1b). The distribution of sites clearly showed a general interest from schools in participating in research projects, not only in cities that host Universities.

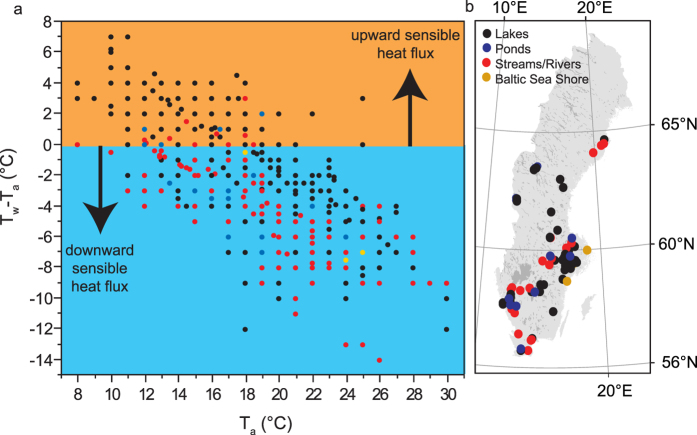

Figure 1. Relationship between air temperature (Ta) and the temperature difference between surface water and the overlying air (Tw-Ta).

All temperatures (1355 paired air and water temperatures) were reported from high school students and measured in 11 small ponds, 49 lakes, 22 streams/rivers and at 2 Baltic Sea shore sampling sites across Sweden (panel b) between August 15 and September 30, 2016. The relationship is linear and significant (panel a; R2 = 0.54, p < 0.0001). The orange color indicates an upward sensible heat flux and the blue color when there is a downward sensible heat flux. The Swedish map was created in ARC GIS, version 10.3.1., using a shape file with open data obtained from the Swedish Meteorological and Hydrological Institute (http://www.smhi.se) under the agreement of the licensing terms specified in Creative Commons Attribution 4.0. (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) The dots in the map and the text were finally modified in Adobe Illustrator version CS6.

Across all water bodies sampled by the students, Ta varied between 6 and 30 °C (median Ta: 19 °C), and Tw varied between 6 and 28 °C (median Tw: 16 °C). Despite a similar Ta and Tw range, Tw-Ta showed substantial variations, ranging between −14 and 7 °C, with a median of −2 °C. The negative median Tw-Ta implies that a majority of the Swedish waters exhibited a downward sensitive heat flux, i.e. from air to water during the day between August to September around the September equinox (Fig. 1), suggesting a suppression of the gas transfer velocity k. Tw-Ta was significantly different between standing (ponds and lakes) and running waters (streams and rivers; non-parametric Wilcoxon test: p < 0.001). This result was expected because streams have higher water turbulence without thermal stratification which strongly influences the heat exchange between water and the overlying air.

We found no relationship between Tw-Ta and the color of water with data from citizen scientists, probably because of two reasons. First, water color estimates from the citizen scientists were not reliable when we calibrated the students’ values against Abs420nm/1cm measurements, suggesting that the Forel-Ule color index scale is too subjective, at least when many individual participants are involved. Second, we did not find a relationship between Abs420nm/1cm and Tw-Ta despite Abs420nm/1cm ranging between 0.001 and 0.4 and Tw-Ta between −7 °C and 5 °C using the 30 water samples for which we determined Abs420nm/1cm (R2 = 0.001, p > 0.05). Thus, our results suggest that the influence of water color on spatial Tw-Ta variability is negligible.

Temporal variation in Tw-Ta – data from high frequency measurements

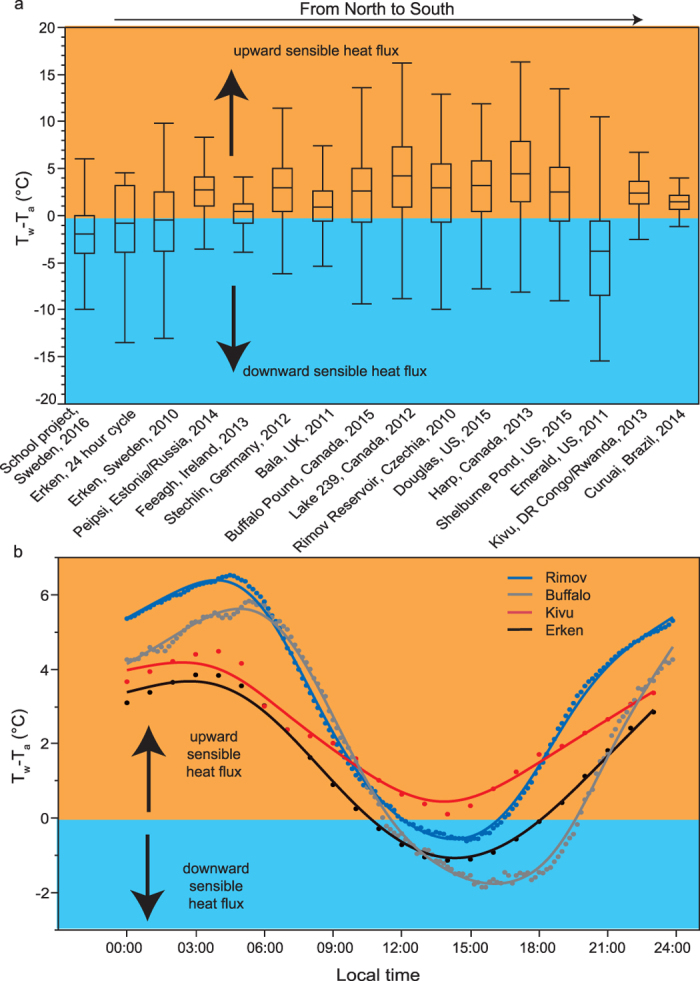

We found that the geographical variation in Tw-Ta from the citizen science project was similar to the intra-annual variation in Tw-Ta of individual lakes (Fig. 2a). The intra-annual Tw-Ta variability was even covered within a single 24-hour period at Lake Erken (second box plot in Fig. 2a). Thus, a very strong diurnal forcing on Tw-Ta exists and is comparable between small and large, shallow and deep, as well as polymictic and dimictic lakes (Fig. 2b). Within 24-hour periods, a shift between downward and upward sensible heat flux is evident for the majority of lakes where the upward heat flux dominates during the 15 hours between 20:00 and 11:00 local time and the downward heat flux dominates during the day between 11:00 and 16:00 local time (Fig. 2b). Our results suggest that the gas transfer velocity k is generally highest around 04:00 during early morning and lowest during early afternoon. The associated large diurnal variations in QH, and in particular the daily shift from upward to downward QH, need to be taken into consideration for in-situ gas emission measurements. At present, gas emission estimates that neglect QH or that are based only on daytime measurements when the gas transfer is suppressed by a downward QH are lower than actual gas emissions from inland waters.

Figure 2. Spatial and temporal variations in the temperature gradient between surface water and the overlying air (Tw-Ta).

Panel a: box plots of Tw-Ta variations across small ponds, lakes, streams/rivers and the shoreline of the Baltic Sea (school project, n = 1355), within 24 hours on September 1, 2014 in the Swedish Lake Erken (n = 24), and within a year during the open water season May to October, based on high-frequency temperature measurements from 14 lakes across the globe (Table 1). Box size corresponds to the interquartile range and whiskers to a distance of 1.5 times the interquartile range from the 25th and 75th quantile, respectively. When more than one year of data was available we chose the time period 2010–2015 and plotted the year with the highest Tw-Ta variance. Panel b: Tw-Ta variations within 24 hours in the most northern and dimictic lake (Erken), a tropical lake (Kivu), a shallow polymictic lake (Buffalo) and a deep small reservoir (Rimov). The Tw-Ta values are median values during May to October from all available years (Table 1). Data points from each lake are connected by a spline function with lambda equal to 0.05. In both panels the orange color indicates when there is an upward sensible heat flux and the blue color when there is a downward sensible heat flux.

On an annual basis (in this study equal to the open water season May to October), we commonly found a net upward sensible heat flux in the 14 diverse lakes. The only clear exception was a small high-altitude lake which showed an annual net downward sensible heat flux (Fig. 2a). Even the most northern lakes, i.e. Lake Erken and Lough Feeagh, occasionally shift from having an annual net downward sensible heat flux to having an annual net upward sensible heat flux. We interpret geographical Tw-Ta differences, in particular Tw-Ta differences between high altitude/latitude and tropical lakes as a result of higher solar radiation during the open water season May to October, which is well known to influence the sensible heat flux24.

Inter-annual variation of Tw-Ta

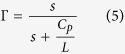

We found a significant decreasing trend over time in yearly median Tw-Ta in Lake Erken during 1989 to 2015 (Mann-Kendall trend test: p < 0.01). Since 1989 Tw-Ta has, on average, decreased by 0.07 °C yr−1. Over the same time period, Ta has significantly increased by, on average, 0.08 °C yr−1 (p < 0.05). On further examination of Tw-Ta, we found that the temperature difference was strongly negatively related to Ta, both across Sweden (Fig. 1) and on an inter-annual scale (Fig. 3). The relationship was remarkably linear. To rule out autocorrelation we examined the relationship from a lake surface energy balance perspective. Under equilibrium conditions, a balance exists between net radiation (RN) and total turbulent heat exchange with the atmosphere:

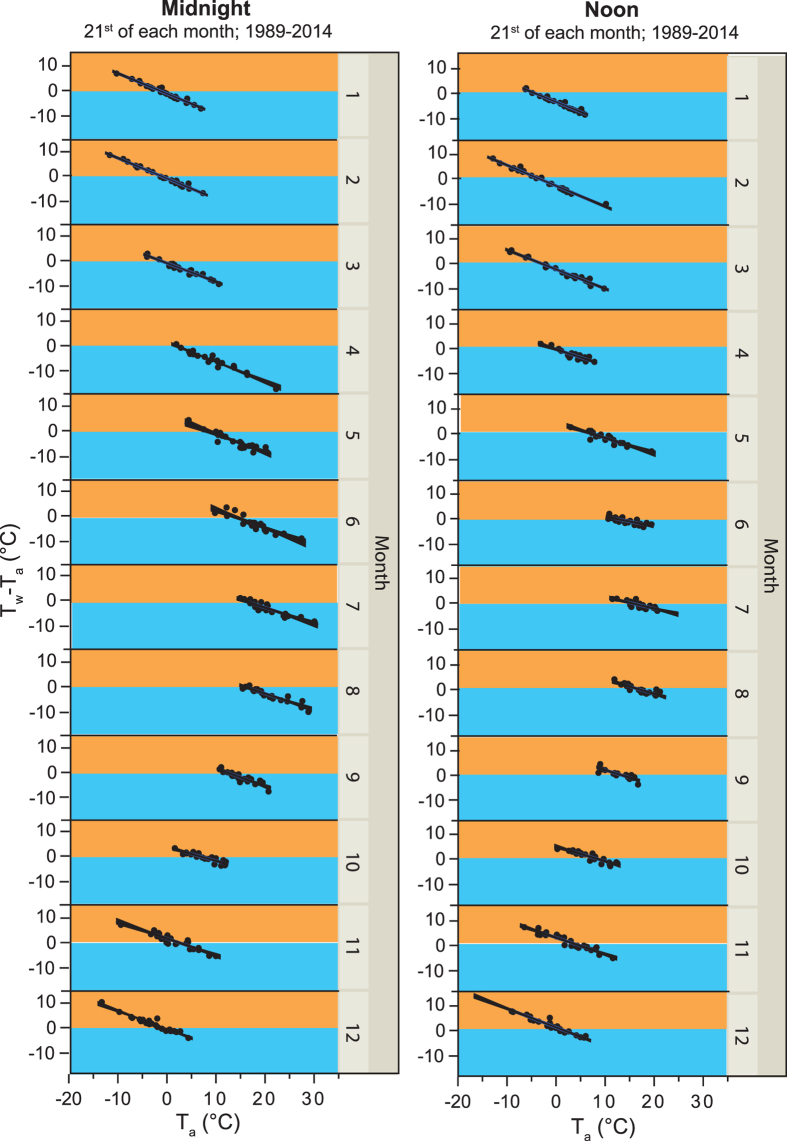

Figure 3. Increasing difference between surface water and air temperature (Tw-Ta) with increasing air temperature (Ta) in Lake Erken.

Shown are year-to-year variations during 1989 to 2015 of in situ Ta and Tw-Ta from Lake Erken at day 21 of each month at midnight (left panel) and noon (right panel). All relationships are linear and highly significant (p < 0.0001). The orange color indicates when there is an upward sensible heat flux and the blue color when there is a downward sensible heat flux.

|

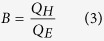

where QE is latent heat flux. What constitutes the surface where these fluxes take place is left ambiguous in this approximate analysis, but is assumed to be thick enough to absorb most of the penetrating shortwave radiation and to minimize temperature fluctuations. QEcan be expressed in a manner analogous to (1) but here we choose to follow a Bowen ratio approach. The Bowen ratio, defined as

|

can be approximated as25

|

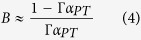

In this expression αPT is a constant generally set to 1.26 for evaporation over saturated surfaces26, and Γ arises from the Penman combination approach to evaporation27. It is defined as

|

where L is the latent heat of vaporization (2.5 × 106 J kg−1) and s is the slope of the saturation specific humidity curve. The Penman combination approach, and the Priestley – Taylor simplification have been used successfully in countless meteorological studies for many years, including studies over bodies of water28,29,30. Their success arises because Γ scales nearly linear with respect to air temperature, and if evaluated at the mean temperature  leads to only small errors in estimates of evaporation, even when Tw-Ta is relatively large25. Combining (1), (3), and (4) we find that (2) can be written as:

leads to only small errors in estimates of evaporation, even when Tw-Ta is relatively large25. Combining (1), (3), and (4) we find that (2) can be written as:

|

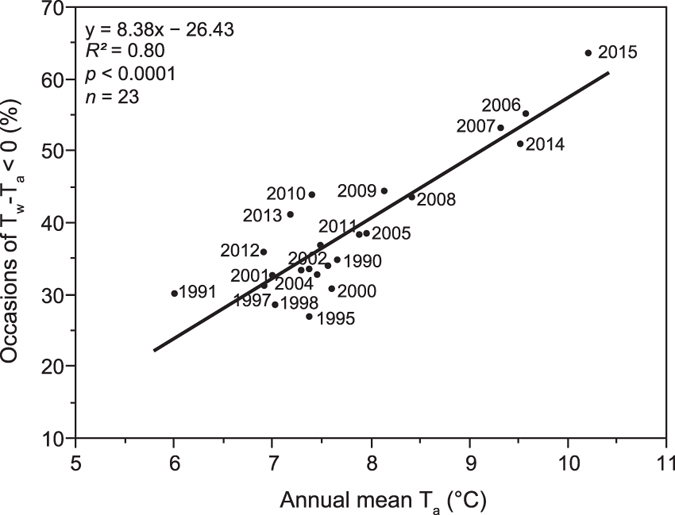

The term in square brackets, a meteorological forcing term, is not directly a function of Ta. Because Γ is nearly linear with respect to Ta it is clear that the linear relationship between Tw-Ta and Ta arises from the function Γ, i.e. through the process of surface evaporation. If this is the case, then the relationship should be detectable at all times and all places provided that radiative heat fluxes are comparable. Radiative heat fluxes usually show large diurnal and, outside the tropics, large seasonal cycles. To eliminate these variations we examined year-to-year variations in Ta and Tw-Ta during a specific hour and a specific day of the year. Regardless of the day of the year or the hour of the day we always observed a strong negative relationship between Ta and Tw-Ta, based on data from Lake Erken (p < 0.0001 for 100 randomly chosen days and hours out of 8760 possible combinations; the relationship is graphically shown in Fig. 3 using Lake Erken data from the 21st day of each month, both at midnight and at noon). Thus, Tw-Ta and thereby QH becomes more negative at higher Ta. Most critical are changes in the diurnal Ta cycle as these changes determine the frequency of upward and downward sensible heat fluxes. Using the longest available time series of year-round high-frequency temperature measurements from Lake Erken (Table 1) we found a strong increase in the occasions of negative Tw-Ta with increasing annual mean Ta since 1989 (Fig. 4). During the coldest year (annual mean Ta: 6 °C in 1991), Tw-Ta reached negative values in 30% of more than 8500 Tw-Ta measurements while Tw-Ta reached negative values in as many as 64% during the warmest year (annual mean Ta: 10 °C in 2015).

Figure 4. Increasing occasions of negative Tw-Ta with increasing annual mean air temperatures.

The percentage of negative Tw-Ta is based on up to 8760 Tw-Ta measurements (8784 Tw-Ta measurements during leap years) that are available for 23 years from Lake Erken during 1989 to 2015. Shown is also a linear regression including the regression equation and regression statistics.

Value of the citizen science project

When we initiated the citizen science project we were unaware of the very strong interest of school teachers to participate in research. The interest continued over the entire project. Some school classes were exceptionally well prepared when they asked their questions via Skype, while other classes provided inaccurate or unfilled protocols or sediment samples instead of water samples. Regardless, the enthusiasm of teachers and students was apparent in the evaluations. Overall, we consider the citizen science project a success. According to the teachers’ evaluations, the students increased their knowledge in natural sciences, and discovered a clear coupling between physics, mathematics, geography, chemistry and biology. For some students who had recently immigrated to Sweden, the experience was the first time that they had the opportunity to visit a remote lake in the Swedish landscape. According to the teachers, this was greatly beneficial. The teachers and students also thought that the media coverage of the students conducting field sampling was very positive. Throughout the project, there were intensive discussions among teachers within a Facebook group of more than 8500 Swedish natural science school teachers. This group was set up by a school teacher a few years ago and provides an excellent platform for this and future citizen science projects involving Swedish schools.

Conclusion

We conclude that the citizen science project was highly successful and resulted in a win-win situation where (1) students increased their knowledge in natural sciences and their awareness of natural processes, and (2) scientists received valuable air and water temperature data. We also conclude that temperature measurements are suitable for a citizen science project as they are easy to perform, cheap, and based on our experience, reliable.

From the data which we received from the citizen scientists and from our own data, we can expect that ongoing and projected global warming will result in increasingly negative Tw-Ta, implying an increase in the downward sensible heat flux. This increase in downward sensible heat flux will enhance water column stability across inland water bodies, which will often result in reduced CO2 and CH4 transfer velocities towards the atmosphere. The global warming induced changes in these transfer velocities should be taken into consideration for future estimates of greenhouse gas emissions from inland waters, an important conclusion which we were able to derive from citizen science.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Weyhenmeyer, G. A. et al. Citizen science shows systematic changes in the temperature difference between air and inland waters with global warming. Sci. Rep. 7, 43890; doi: 10.1038/srep43890 (2017).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Acknowledgments

Financial support was received from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 643052 (C-CASCADES project), the Swedish Research Council (Grant 2016–04153) and from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation (KAW project). P.A-S. acknowledges the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) for financial support under grant 2011/23594–8 and the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) for her scholarship. RIW was funded by EUSTACE (EU Surface Temperature for All Corners of Earth) which received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Programme for Research and Innovation. This work profited from the international networks abbreviated as GLEON, NETLAKE, SAFER, and DOMQUA. We thank Jason Tallant for sharing high frequency data from Lake Douglas. Operation of the Lake ESP at Lake Stechlin was funded by the German Ministry of Education and Science (BMBF), the Leibniz Foundation and the DFG project “Aquameth” (GR1540:/21-1). Operation of the Harp Lake buoy was funded by the Ontario Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. The monitoring at Rimov Reservoir was supported by the Czech Science Foundation, project No. 15–13750 S, and data from Shelburne Pond, USA, were made possible by a grant from the Kelsey Trust. Many thanks go to the 100 Swedish teachers and > 3500 high school students who took part in the citizen science project. Finally, we thank numerous people at the Communication Unit of the Faculty of Science and Technology at Uppsala University who helped organizing the citizen science project, in particular Elin Eriksson, Mats Kamsten, Johanna Lundmark, Karin Beronius, Maja Garde Lindholm, Tobias Blom, Anneli Björkman, Marie Chajara Svensson and Sami Vihriälä.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author Contributions G.W. designed the study, she was responsible for the citizen science project, performed data analyses and wrote the manuscript. M.M., J.S., W.T., H.P.G., P.A.S., H.B., E.E., J.H., K.K., G.K., D.P., J.R., S.S. and I.W. all contributed with data, and they made substantial contributions to the data analyses and manuscript drafting.

References

- Rowe G. & Frewer L. J. Public participation methods: A framework for evaluation. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 25, 3–29 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Silvertown J. A new dawn for citizen science. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 24, 467–471, doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.017 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons J., Lukyanenko R. & Wiersma Y. Easier citizen science is better. Nature 471, 37–37, doi: 10.1038/471037a (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennett R., Danielsen F. & Silvius K. M. Citizen science is not enough on its own. Nature 521, 161–161 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battin T. J. et al. The boundless carbon cycle. Nature Geoscience 2, 598–600, doi: 10.1038/ngeo618 (2009). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond P. A. et al. Global carbon dioxide emissions from inland waters. Nature 503, 355–359, doi: 10.1038/nature12760 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanninkhof R. et al. Global ocean carbon uptake: magnitude, variability and trends. Biogeosciences 10, 1983–2000, doi: 10.5194/bg-10-1983-2013 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woolway R. I. et al. Automated calculation of surface energy fluxes with high-frequency lake buoy data. Environ. Modell. Softw. 70, 191–198, doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2015.04.013 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thiery W. et al. LakeMIP Kivu: evaluating the representation of a large, deep tropical lake by a set of one-dimensional lake models. Tellus Ser. A-Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanol. 66, doi: 10.3402/tellusa.v66.21390 (2014). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mammarella I. et al. Carbon dioxide and energy fluxes over a small boreal lake in Southern Finland. Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences 120, 1296–1314, doi: 10.1002/2014jg002873 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Polsenaere P. et al. Thermal enhancement of gas transfer velocity of CO2 in an Amazon floodplain lake revealed by eddy covariance measurements. Geophysical Research Letters 40, 1734–1740, doi: 10.1002/grl.50291 (2013). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutgersson A. & Smedman A. Enhanced air-sea CO2 transfer due to water-side convection. Journal of Marine Systems 80, 125–134, doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2009.11.004 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis D. F. et al. Enhancing Surface Methane Fluxes from an Oligotrophic Lake: Exploring the Microbubble Hypothesis. Environmental Science & Technology 49, 873–880, doi: 10.1021/es503385d (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre S. et al. Buoyancy flux, turbulence, and the gas transfer coefficient in a stratified lake. Geophysical Research Letters 37, 5, doi: 10.1029/2010gl044164 (2010). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Podgrajsek E., Sahlee E. & Rutgersson A. Diel cycle of lake-air CO2 flux from a shallow lake and the impact of waterside convection on the transfer velocity. Journal of Geophysical Research-Biogeosciences 120, 29–38, doi: 10.1002/2014jg002781 (2015). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre S., Romero J. R. & Kling G. W. Spatial-temporal variability in surface layer deepening and lateral advection in an embayment of Lake Victoria, East Africa. Limnology and Oceanography 47, 656–671 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- MacIntyre S. & Melack J. M. In Encyclopedia of Inland Waters(ed G. E. Likens) 603–612 (Oxford, UK, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- Morris D. P. et al. The attentuation of solar UV radiation in lakes and the role of dissolved organic carbon. Limnology and Oceanography 40, 1381–1391 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Rose K. C., Winslow L. A., Read J. S. & Hansen G. J. A. Climate induced warming of lakes can be either amplified or supressed by trends in water clarity. Limnology and Oceanography Letters 1, 44–53 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Weyhenmeyer G. A., Prairie Y. T. & Tranvik L. J. Browning of boreal freshwaters coupled to carbon-iron interactions along the aquatic continuum. Plos One 9, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088104 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteith D. T. et al. Dissolved organic carbon trends resulting from changes in atmospheric deposition chemistry. Nature 450, 537–U539 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garaba S. P., Friedrichs A., Voss D. & Zielinski O. Classifying Natural Waters with the Forel-Ule Colour Index System: Results, Applications, Correlations and Crowdsourcing. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 12, 16096–16109, doi: 10.3390/ijerph121215044 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helsel D. & Hirsch R. Statistical methods in water resources. (Elsevier, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- Duffle J. A. & Beckman W. A. Solar engineering of thermal processes. (John Wiley and Sons, 1980). [Google Scholar]

- Garratt J. R. The atmospheric boundary layer. 316 (Cambridge University Press, 1992). [Google Scholar]

- Priestley C. H. B. & Taylor R. J. Assessment of surface heat-flux and evaporation using large-scale parameters. Mon. Weather Rev. 100, 81−+, doi: (1972). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penman H. L. Natural evaporation from open water, bare soil and grass. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series a-Mathematical and Physical Sciences 193, 120-&, doi: 10.1098/rspa.1948.0037 (1948). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleugh H. A., Leuning R., Mu Q. Z. & Running S. W. Regional evaporation estimates from flux tower and MODIS satellite data. Remote Sensing of Environment 106, 285–304, doi: 10.1016/j.rse.2006.07.007 (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moran M. S. et al. Combining the Penman-Monteith equation with measurements of surface temperature and reflectance to estimate evaporation rates of semiarid grassland. Agric. For. Meteorol. 80, 87–109, doi: 10.1016/0168-1923(95)02292-9 (1996). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan N., White S. M., Worrall F. & Whelan M. J. Sensitivity analysis and identification of the best evapotranspiration and runoff options for hydrological modelling in SWAT-2000. Journal of Hydrology 332, 456–466, doi: 10.1016/j.jhydrol.2006.08.001 (2007). [DOI] [Google Scholar]