Significance

Root hairs are unicellular extensions of the rhizodermis, providing anchorage and an increase in surface area for nutrient and water uptake. Their fast, tip-focused growth showcases root hairs as an excellent genetic model to study physiological and developmental processes on the cellular level. We uncovered a root hair phenotype that is dependent on putative Arabidopsis orthologs of the Guided Entry of Tail-anchored (TA) proteins (GET) pathway, which facilitates membrane insertion of TA proteins in yeast and mammals. We found that plants have evolved multiple paralogs of specific GET pathway components, albeit in a compartment-specific manner. In addition, we show that differential expression of pathway components causes pleiotropic growth defects, suggesting alternative pathways for TA insertion and additional functions of GET in plants.

Keywords: GET pathway, TA proteins, SNAREs, ER membrane, root hairs

Abstract

Soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) proteins are key players in cellular trafficking and coordinate vital cellular processes, such as cytokinesis, pathogen defense, and ion transport regulation. With few exceptions, SNAREs are tail-anchored (TA) proteins, bearing a C-terminal hydrophobic domain that is essential for their membrane integration. Recently, the Guided Entry of Tail-anchored proteins (GET) pathway was described in mammalian and yeast cells that serve as a blueprint of TA protein insertion [Schuldiner M, et al. (2008) Cell 134(4):634–645; Stefanovic S, Hegde RS (2007) Cell 128(6):1147–1159]. This pathway consists of six proteins, with the cytosolic ATPase GET3 chaperoning the newly synthesized TA protein posttranslationally from the ribosome to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane. Structural and biochemical insights confirmed the potential of pathway components to facilitate membrane insertion, but the physiological significance in multicellular organisms remains to be resolved. Our phylogenetic analysis of 37 GET3 orthologs from 18 different species revealed the presence of two different GET3 clades. We identified and analyzed GET pathway components in Arabidopsis thaliana and found reduced root hair elongation in Atget lines, possibly as a result of reduced SNARE biogenesis. Overexpression of AtGET3a in a receptor knockout (KO) results in severe growth defects, suggesting presence of alternative insertion pathways while highlighting an intricate involvement for the GET pathway in cellular homeostasis of plants.

Plants show remarkable acclimation and resilience to a broad spectrum of environmental influences as a consequence of their sedentary lifestyle. On the cellular level, such flexibility requires genetic buffering capacity as well as fine-tuned signaling and response systems. Soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment protein receptor (SNARE) proteins make a critical contribution toward acclimation (1, 2). Their canonical function facilitates membrane fusion through tight interaction of cognate SNARE partners at vesicle and target membranes (3). This vital process guarantees cellular expansion through addition of membrane material, cell plate formation, and cargo delivery (4, 5). SNARE proteins are also involved in regulating potassium channels and aquaporins (6–8).

Most SNARE proteins are Type II oriented and referred to as tail-anchored (TA) proteins with a cytosolic N terminus and a single C-terminal transmembrane domain (TMD) (9). TA proteins are involved in vital cellular processes in all domains of life, such as chaperoning, ubiquitination, signaling, trafficking, and transcript regulation (10–13). The nascent protein is almost fully translated when the hydrophobic TMD emerges from the ribosome, requiring shielding from the aqueous cytosol to guarantee protein stability, efficient folding, and function (14). One way of facilitating this posttranslational insertion is by proteinaceous components of a Guided Entry of Tail-anchored proteins (GET) pathway that was identified in yeast and mammals (15, 16).

In yeast, recognition of nascent TA proteins is accomplished through a tripartite pretargeting complex at the ribosome consisting of SGT2, GET5, and GET4. This complex binds to the TMD and delivers the TA protein to the cytosolic ATPase GET3 (17, 18). GET3 arranges as zinc-coordinating homodimer and shuttles the client protein to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane receptors GET1 and GET2, which finalize insertion of the TA protein (15, 19, 20).

This GET pathway is thought to be the main route for TA protein insertion into the ER, but surprisingly, its loss in yeast is only conditionally lethal (15). Conversely, lack of the mammalian GET3 orthologs TRC40 (transmembrane domain recognition complex of 40 kDa) leads to embryo lethality in mice, complicating global physiological analyses (21). Nevertheless, a handful of recent studies have started to analyze individual physiological consequences of the GET pathway in vivo using tissue-specific knockout (KO) approaches and observed that its function is required for a diverse range of physiological processes, such as insulin secretion, auditory perception, and photoreceptor function, in animals (22–24). A high degree of evolutionary conservation is often assumed, and it has been recognized that some components of the GET pathway are present in Arabidopsis thaliana (25, 26). However, considering the specific physiological roles of the GET pathway observed in yeast and mammals, its significance cannot be straightforwardly extrapolated across eukaryotes. A global genetic dissection of the pathway in a multicellular organism, let alone in plants, is currently lacking.

GET3/TRC40 are distant paralogs of the prokaryotic ArsA (arsenite-translocating ATPase), a protein that is part of the arsenic detoxification pathway in bacteria (27). Evidence points toward the GET pathway—albeit at a simpler scale—that exists already in Archaebacteria (10, 28). Because yeast and mammals are closely related in the supergroup of Opisthokonts (29), limiting any comparative power, we aimed to investigate pathway conservation in other eukaryotes. We also wanted to understand the impact that lack of GET pathway function has on plant development, considering that it started entering the textbooks as a default route for TA protein insertion.

Our results show that loss of GET pathway function in A. thaliana impacts on root hair length. This phenotype coincides with reduced protein levels at the plasma membrane of an important root hair-specific SNARE, conforming to the role of the GET pathway in TA protein insertion. However, similarly to yeast, no global pleiotropic phenotypes were observed, pointing to the existence of functional backup. However, ectopic overexpression of the cytosolic ATPase AtGET3a in the putative receptor KO Atget1 leads to severe growth defects, underscoring pathway conservation while implying an intricate role of the GET pathway in cellular homeostasis of plants.

Results

GET3 Paralogs Might Have Evolved as Early as Archaea.

To identify potential orthologs of GET candidates, we used in silico sequence comparison (BLASTp and National Center for Biotechnology Information) of yeast and human GET proteins against the proteome of 16 different species from 13 phyla (Tables 1 and 2). Candidate sequences were assembled in a phylogenetic tree that, surprisingly, reveals that two distinct GET3 clades, which we termed GET3a and GET3bc, respectively, exist in Archaeplastida and SAR (supergroup of stramenopiles, alveolates, and Rhizaria) but do not exist in Opisthokonts (yeast and animals) and Amoebozoa. The deep branching of the tree implies that duplication events must have occurred early in the evolution of eukaryotes (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, the recently identified phylum of Lokiarchaeota, which is thought to form a monophyletic group with eukaryotes (30), expresses two distinct GET3 orthologs, one of which aligns within the GET3bc clade while lacking some of the important sequence features of eukaryotic GET3 (Fig. S1A). This observation suggests that the last eukaryotic common ancestor had already acquired two copies of GET3.

Table 1.

Accession numbers of GET3/TRC40/ArsA orthologs of clade a used for the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 1 and their putative GET1/WRB and GET4/TRC40 orthologs identified via BLASTp search

| Phylum and species | GET3/TRC40 orthologs | Up-/downstream orthologs | ||

| Accession no. | Length (aa) | GET1/WRB | GET4/TRC35 | |

| Eubacteria | ||||

| Proteobacteria | ||||

| Escherichia coli | KZO75668 | 583* | Not found | Not found |

| Proteoarchaeota | ||||

| Lokiarchaeota | ||||

| Lokiarchaeum sp. | KKK44956 | 338 | Not found | Not found |

| Opisthokonta | ||||

| Chordata | ||||

| Homo sapiens | NP_004308 | 348 | NP_004618 | NP_057033 |

| Ascomycota | ||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | AAT93183 | 354 | NP_011495 | NP_014807 |

| Amoebozoa | ||||

| Discosea | ||||

| Acanthamoeba castellanii | XP_004368068 | 330 | XP_004353131 | XP_004367722 |

| Mycetozoa | ||||

| Dictyostelium purpureum | XP_003289495 | 330 | Not found | XP_003283186 |

| Archaeplastida | ||||

| Angiospermae | ||||

| Arabidopsis thaliana | NP_563640 | 353 | NP_567498 | NP_201127 |

| Medicago truncatula | XP_013444959 | 358 | XP_003629131 | XP_003591984 |

| Brachypodium distachyon | XP_003578462 | 363 | XP_003564144 | XP_003569076 |

| Amborella trichopoda | XP_006857946 | 353 | XP_006855737 | ERM96291 |

| Lycopodiophyta | ||||

| Selaginella moellendorffii | XP_002973461 | 360 | Not found | XP_002969945 |

| XP_002981415 | ||||

| Marchantiophyta | ||||

| Marchantia polymorpha | OAE26618 | 370 | OAE20217 | OAE20690 |

| Bryophyta | ||||

| Physcomitrella patens | XP_001758936 | 365 | XP_001760426 | XP_001760372 |

| XP_001774198 | 365 | XP_001758146 | ||

| Chlorophyta | ||||

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | XP_001693332 | 319 | XP_001695038 | XP_001695333 |

| Rhodophyta | ||||

| Galdieria sulphuraria | XP_005708637 | 706* | XP_005707118 | XP_005704684 |

| SAR | ||||

| Chromerida | ||||

| Vitrella brassicaformis | CEM03518 | 412 | Not found | CEL97893 |

| Heterokontophyta | ||||

| Nannochloropsis gaditana | EWM27451 | 370 | EWM21897 | EWM27335 |

| Chromalveolata | ||||

| Cryptophyta | ||||

| Guillardia theta | XP_005837457 | 310 | XP_005829401 | XP_005841994 |

Tandem GET3.

Table 2.

Accession numbers of GET3/TRC40/ArsA orthologs of clade bc used for the phylogenetic tree in Fig. 1 and their in silico prediction of an N-terminal signal/transit peptide using three different prediction tools (TargetP 1.1, ChloroP 1.1, and Predotar v1.03)

| Phylum and species | GET3/TRC40 orthologs | Signal/transit peptide prediction | |||

| Accession no. | Length (aa) | TargetP 1.1 | ChloroP 1.1 | Predotar v1.03 | |

| Eubacteria | |||||

| Proteobacteria | |||||

| Escherichia coli | KZO75668 | 583* | Non-Eukaryote | ||

| Proteoarchaeota | |||||

| Lokiarchaeota | |||||

| Lokiarchaeum sp. | KKK42590 | 329 | Non-Eukaryote | ||

| Archaeplastida | |||||

| Angiospermae | |||||

| A. thaliana | NP_187646 | 433 | C | C | C |

| NP_200881 | 391 | M | C | M | |

| Medicago truncatula | XP_003591867 | 406 | C | C | Possibly C |

| XP_013455984 | 381 | C | C | C | |

| Brachypodium distachyon | XP_003570659 | 403 | M | C | M |

| XP_010239988 | 371 | M | — | M | |

| Amborella trichopoda | XP_006827440 | 407 | C | C | C |

| Lycopodiophyta | |||||

| Selaginella moellendorffii | XP_002974288 | 432 | C | C | Possibly M |

| Marchantiophyta | |||||

| Marchantia polymorpha | OAE21403 | 432 | C | — | C |

| Bryophyta | |||||

| Physcomitrella patens | XP_001781368 | 331 | M | C | Possibly M |

| XP_001764873 | 359 | N terminus incomplete | |||

| Chlorophyta | |||||

| Chlamydomonas reinhardtii | XP_001702275 | 513† | M | C | C |

| Rhodophyta | |||||

| Galdieria sulphuraria | XP_005705663 | 481 | — | — | Possibly ER |

| XP_005703923 | 757* | M | C | Possibly C | |

| SAR | |||||

| Heterokontophyta | |||||

| Nannochloropsis gaditana | EWM30283 | 817* | M | — | Possibly C |

| Chromerida | |||||

| Vitrella brassicaformis | CEM11669 | 809* | M | — | Possibly ER |

| Chromalveolata | |||||

| Cryptophyta | |||||

| Guillardia theta | XP_005822752 | 418 | S | C | ER |

C, chloroplast; M, mitochondrion; S, signal peptide.

Tandem GET3.

Second P-loop motif at C terminus of protein.

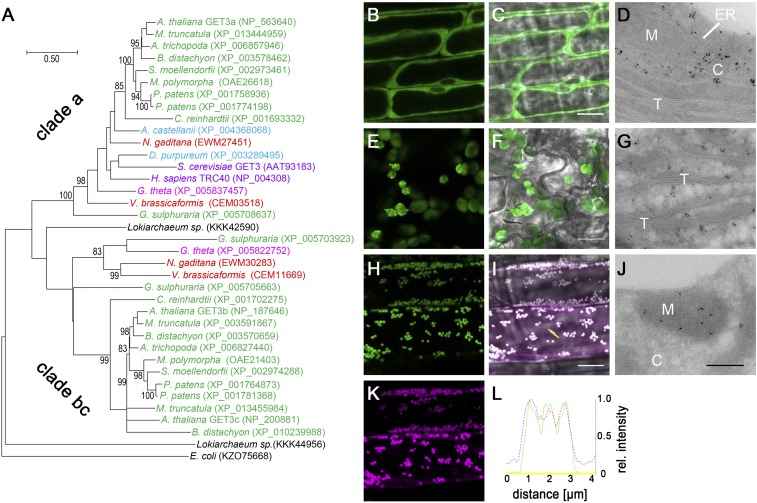

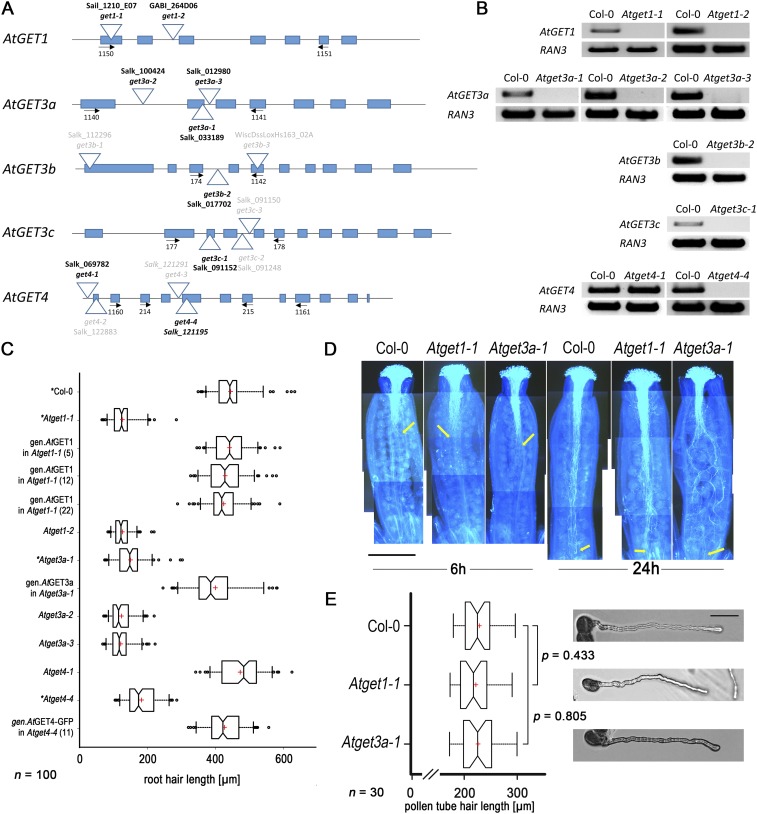

Fig. 1.

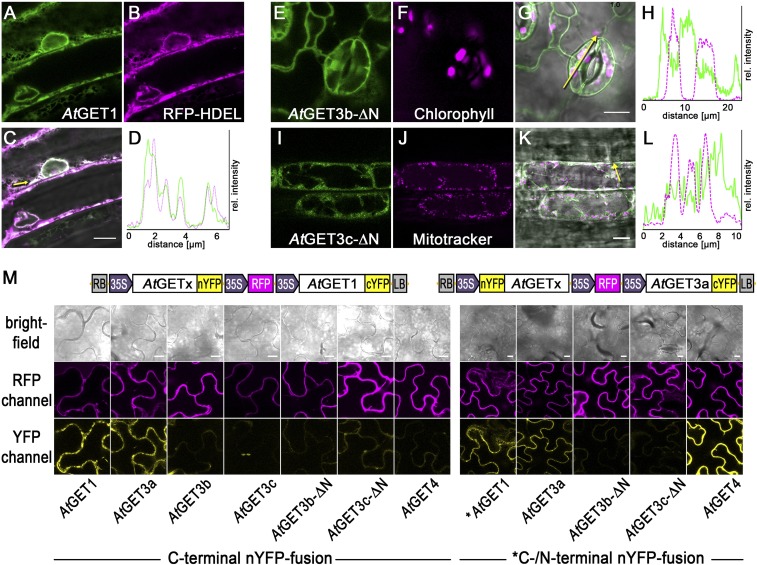

Analysis of GET3 orthologs of different species. (A) Maximum likelihood rooted phylogenetic tree of GET3 orthologs revealing two major GET3 branches; 1,000 bootstraps were applied, and confidence ratios above 70 are included at nodes. Species color code: black, Eubacteria/Proteoarchaeota; purple, Opisthokonta; light blue, Amoebozoa; green, Archaeplastida; red, SAR; magenta, Chromalveolata. (Scale bar: changes per residue.) (B–L) Subcellular localization of (B–D) AtGET3a, (E–G) AtGET3b, and (H–L) AtGET3c in stably transformed A. thaliana using CLSM and TEM analysis (controls in Fig. S2). (K) AtGET3c-GFP–expressing specimens were treated with MitoTracker Orange to counterstain mitochondria. (L) Line histogram in (I) merged image along the yellow arrow confirms colocalization. C, cytosol; M, mitochondrion; T, thylakoid. (Scale bars: B, C, E, F, H, I, and K, 10 µm; D, G, and J, 300 nm.)

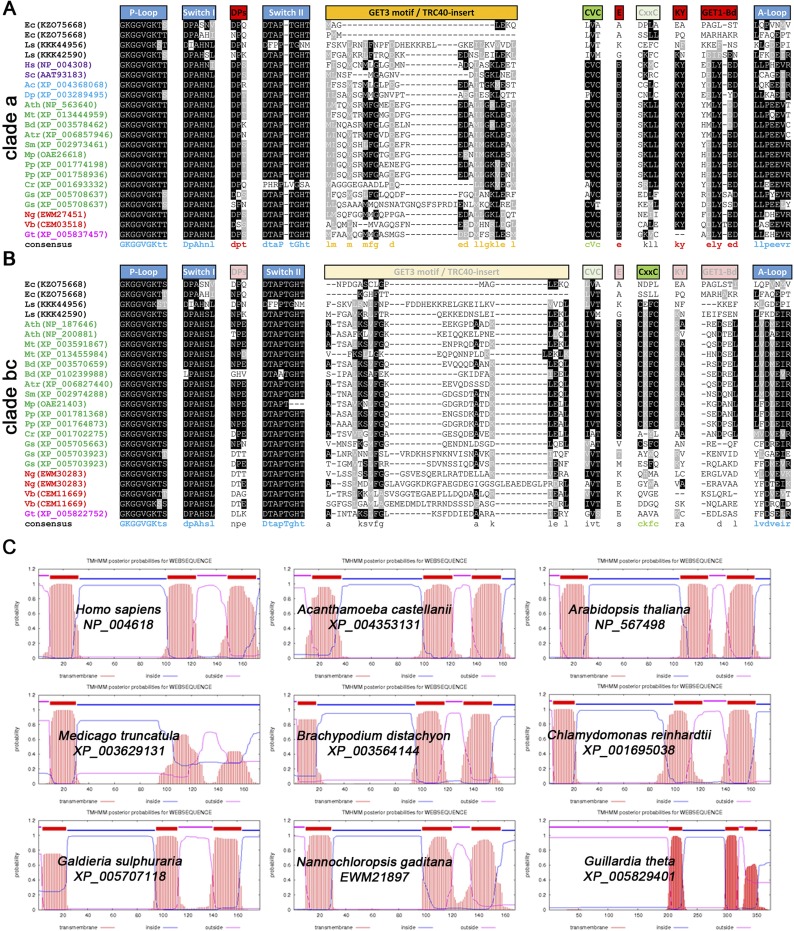

Fig. S1.

Sequence and structural evaluation of GET orthologs. Excerpts of multiple sequence alignments of (A) clade a and (B) clade bc GET3 orthologs showing conserved motives. ATPase motifs are in blue (P loop and Switches I and II), and GET1 binding motifs are in red (conserved only in clade a). Cysteine residues (CVC and CxxC motives) important for metal binding/dimerization are in light green. Absence or partial conservation of motives is depicted through opaqueness of boxes above the sequences. Tandem sequences were split and treated as two individual GET3 orthologs for accessions: KZO75668, XP_005708637, XP_005703923, EWM30283, and CEM11669. Ac, Acanthamoeba castellanii; Ath, A. thaliana; Atr, Amborella trichopoda; Bd, Brachypodium distachyon; Cr, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii; Dp, Dictyostelium purpureum; Ec, Escherichia coli; Gs, Galdieria sulphuraria; Gt, Guillardia theta; Hs, Homo sapiens; Ls, Lokiarchaeum sp.; Mp, Marchantia polymorpha; Mt, Medicago truncatula; Ng, Nannochloropsis gaditana; Pp, Physcomitrella patens; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Sm, Selaginella moellendorffii; Vb, Vitrella brassicaformis. (C) Exemplary TMD prediction of membrane domains of ScGET1, HsWRB, and putative orthologs in different eukaryotic species (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/).

In Rhodophytes and higher Angiospermae, a third GET3bc paralog branched off. Interestingly, the tandem ATPase motif—likely a consequence of gene duplication in the prokaryotic ArsA and suggested to be a key difference between ArsA and GET3/TRC40 homologs (28)—is not found in either of two Lokiarchaeota GET3; conversely, in Rhodophytes and SAR species, GET3 paralogs exist that contain duplications (Tables 1 and 2). Importantly, such repeats are not restricted to the GET3bc clade but also, are found among red algae GET3a orthologs (e.g., XP_005708637). Comparing sequence conservation of GET3 orthologs reveals that residues important for ATPase function are maintained in all candidates (Fig. S1 A and B). However, the sites for GET1 binding and the methionine-rich GET3 motif (31, 32) are only conserved in GET3a candidates of eukaryotes, concurring with the presence of GET1 and GET4 orthologs in most of these species (Table 1).

Strikingly, in silico analysis of the N termini of the identified GET3 orthologs predicts for almost all GET3bc—but not for GET3a candidates—the presence of a transit peptide for mitochondrial or chloroplastic import (Table 2). This observation is also in line with the fact that GET3bc proteins are, on average, larger than their GET3a paralogs (Tables 1 and 2), matching the length range of targeting sequences for the bioenergetic organelles.

Distinct Differences in Subcellular Localization of AtGET3 Paralogs.

The three GET3 paralogs of A. thaliana were in silico-predicted to localize to the cytosol (AtGET3a; At1g01910), chloroplast (AtGET3b; At3g10350), and mitochondria (AtGET3c; At5g60730), respectively (Tables 1 and 2). To corroborate these predictions, stably transformed, A. thaliana Ubiquitin10 promoter (PUBQ10)-driven GFP fusions were generated (33). Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analyses reveal distinct subcellular localization patterns for three AtGET3 paralogs (Fig. 1 B–L and Fig. S2): AtGET3a is detected in the cytosol, AtGET3b localizes to chloroplasts, and AtGET3c localizes to mitochondria.

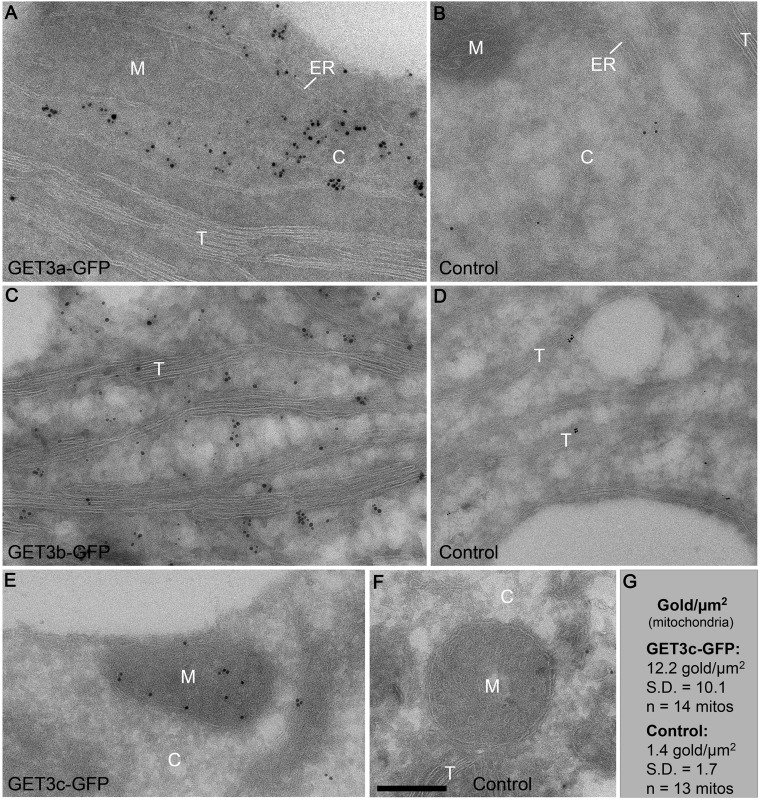

Fig. S2.

Expanded view of localization analysis of AtGET orthologs (original TEM images shown in Fig. 1 D, G, and J). High-resolution images and controls of TEM analysis shown in parts in Fig. 1 D, G, and J. TEM immunogold labeling of GFP in (A) AtGET3a-GFP (cytoplasm), (C) AtGET3b-GFP (chloroplasts), and (E) AtGET3c-GFP (mitochondria) expressing seedlings using ultrathin thawed cryosections of cotyledons. Control experiments using seedlings missing the corresponding fusion protein are shown in B, D, and F. G shows a statistical analysis of the relatively weak but specific mitochondrial gold labeling in AtGET3c-GFP seedlings. C, cytoplasm; M, mitochondrion; T, thylakoid. (Scale bar: A–F, 300 nm.)

To resolve subplastidic localization of AtGET3b-GFP and AtGET3c-GFP, we used TEM analysis. Immunogold labeling indicates that AtGET3b localizes to the stroma of chloroplasts (Fig. 1G and Fig. S2 C and D) and that AtGET3c localizes to the matrix of mitochondria (Fig. 1J and Fig. S2 E–G). The mitochondrial localization of AtGET3c had previously been reported in transiently transformed A. thaliana cell culture to localize to the outer mitochondrial membrane (26). By contrast, the immunogold data and high-resolution CLSM colocalization analysis of stably transformed A. thaliana seedlings using MitoTracker Orange consistently suggest a matrix localization for AtGET3c (Fig. 1 H–L). These results are also in compliance with the presence of a transit peptide, a hallmark of organellar import (34).

Identifying the Membrane Receptor for AtGET3a.

Previous analyses have indicated that the ScGET1 ortholog is missing in plants (26). Refining search parameters and using HsWRB (tryptophan-rich basic protein) as template, we identified At4g16444 of A. thaliana. Sequence conservation of GET1 orthologs seems weaker than among GET3 candidates, but comparing TMD prediction using TMHMM (www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) reveals striking structural similarity between the orthologs of different species (Fig. S1C). All GET1 candidates that we identified are predicted to have the typical three TMD structures of GET1/WRB with a luminal N terminus and a cytosolic C terminus as well as a cytosolic coiled coil domain between first and second TMDs (35). Additionally, publicly available microarray data confirm constitutive and well-correlated expression pattern for the putative AtGET1 and AtGET3a in accordance with a potential housekeeping function of the candidates (Fig. S3D).

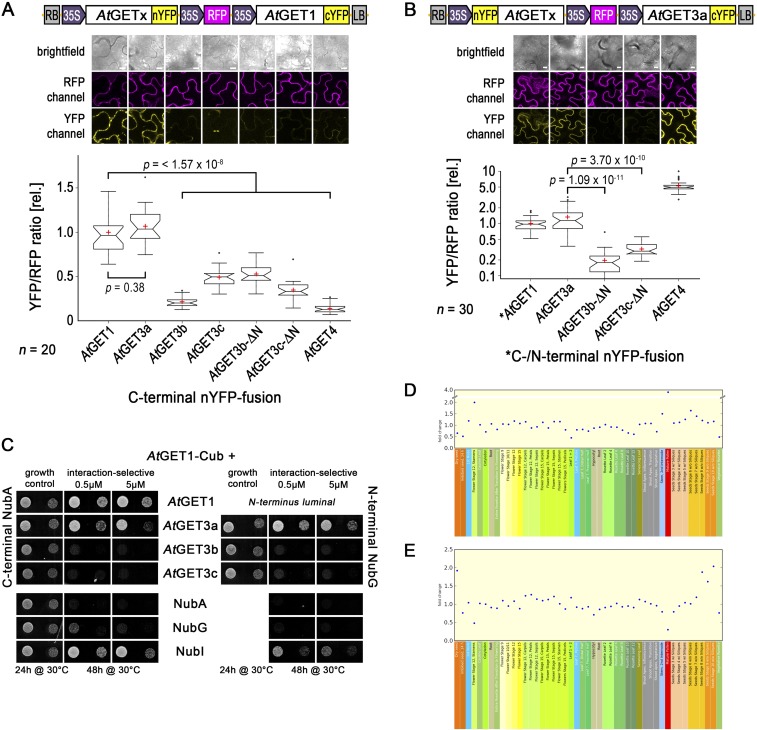

Fig. S3.

Interaction analysis of AtGET pathway orthologs. (A and B) Complete rBiFC analysis of (A) AtGET1 and (B) AtGET3a with GET pathway orthologs and truncated constructs. Boxed cartoons show construct design above representative images of epidermal cells from transiently transformed Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Larger versions of confocal images are presented in Fig. 2M. YFP/RFP mean fluorescence intensities from 20 different leaf sections were calculated and ratioed against the average YFP/RFP ratio of AtGET1 homodimerization or AtGET3a–AtGET1 interaction. Center lines of boxes represent medians, with outer limits at 25th and 75th percentiles. Notches indicate 95% confidence intervals; Tukey whiskers extend to 1.5× interquartile range, outliers are depicted as black dots, and red crosses mark sample means. (Scale bars: 10 µm.) (C) Split Ubiquitin interaction analysis in yeast. (Left) C-terminally NubA- or (Right) N-terminally NubG-tagged AtGET3 orthologs were coexpressed with AtGET1-Cub in yeast. Untagged NubA, NubG, or NubI were used as negative (NubG or NubA) or positive (NubI) controls, respectively. Growth on interaction-selective media was detected for yeast coexpressing AtGET1-Cub and AtGET1-NubA as well as AtGET3a-Nub fusion. The plastidic AtGET3 paralogs do not interact with AtGET1 in yeast in either tag orientation complementing the rBiFC analysis. (D and E) eFP browser screenshots showing fold changes in expression ratios of (D) AtGET1 with AtGET3a and (E) AtGET3a with AtGET4 over different developmental stages from publicly available microarray data (bar.utoronto.ca/efp_arabidopsis/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi).

To experimentally validate At4g16444 as AtGET1, we devised localization and interaction studies. CLSM analysis of A. thaliana leaves that stably coexpress an ER marker protein [secreted red fluorescent protein (secRFP-HDEL)] and PUBQ10-driven, C-terminally GFP-tagged AtGET1 showed a high degree of colocalization (Fig. 2 A–D). Because both ScGET1 and HsWRB also localize to the ER membrane, this lends further support for At4g16444 being the A. thaliana GET1 ortholog (20, 35). Additionally, direct in planta interaction analysis using coimmunoprecipitation mass spectrometry (CoIP-MS) of AtGET3a-GFP–expressing lines identified At4g16444 with high confidence consistently in two biological replicates among the interactors (Dataset S1).

Fig. 2.

Interaction analysis among A. thaliana GET pathway orthologs. (A–D) At4g16444, the putative AtGET1, C-terminally tagged with GFP in stably transformed A. thaliana coexpressing the ER marker RFP-HDEL. (D) Line histograms along yellow arrows in C confirm colocalization. (E–L) CLSM analysis of N-terminally truncated AtGET3b and AtGET3c candidates. Counterimaging using autofluorescence of (F) chlorophyll or (J) MitoTracker Orange allows (H and L) line histograms in (G and K) merged images along yellow arrows that corroborate cytosolic retention. (M) Exemplary confocal images of rBiFC analysis of (Left) AtGET1 and (Right) AtGET3a with GET pathway orthologs and truncated constructs. Boxed cartoons show construct design above exemplary images of transiently transformed Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. A statistical analysis of the data is in Fig. S3. (Scale bars: 10 µm.)

To test interaction between AtGET1 and all three different AtGET3 paralogs, we used the mating-based Split-Ubiquitin System (SUS) (36). The putative AtGET1 forms homodimers with a C-terminally tagged NubA fusion and interacts with AtGET3a (tagged at either termini) but does not interact with the organellar localized AtGET3b or AtGET3c (Fig. S3C). Even when an N-terminal NubG tag presumably masks the transit peptides, which might prevent organellar import and cause their cytosolic retention, an interaction with AtGET1 cannot be observed.

To understand whether the physical separation of AtGET3b/c prevents interaction with AtGET1, we truncated the first 68 aa of AtGET3b and 50 aa of AtGET3c, which lead to their cytosolic localization (Fig. 2 E–L). We applied ratiometric bimolecular fluorescence complementation (rBiFC) (37) to assess whether such artificial mislocalization renders AtGET3b/c susceptible to interaction with AtGET1. Clearly, AtGET1 homodimerizes and interacts with the cytosolic AtGET3a but does not homodimerize or interact with the plastidic AtGET3 paralogs or their transit peptide deletion versions (Fig. 2M and Fig. S3 A and B), confirming that a change in localization does not alter binding behavior. This absence of interaction seems consistent with the lack of a GET1-binding motif (32, 38) in the sequences of AtGET3b/c, further indicating that these likely lack functional redundancy with AtGET3a.

To test this hypothesis before phenotypic complementation, we assessed heterodimerization with AtGET3a. Here, we also included the putative upstream binding partner of AtGET3a, AtGET4 (At5g63220), which we identified through in silico analysis. The expression pattern of AtGET4 resembles that of AtGET3a (Fig. S3E), and the protein localizes to the cytosol (Fig. S7B). rBiFC analysis substantiates that AtGET3a interacts with AtGET1, itself, and AtGET4 but fails to heterodimerize with AtGET3b/c. Both proteins were expressed in their truncated, cytosolic form; hence, the lack of interaction cannot be attributed to compartmentalization (Fig. 2M and Fig. S3 A and B). Because dimerization of ScGET3 is a prerequisite for function (31), this result also negates functional redundancy between GET3 paralogs.

Fig. S7.

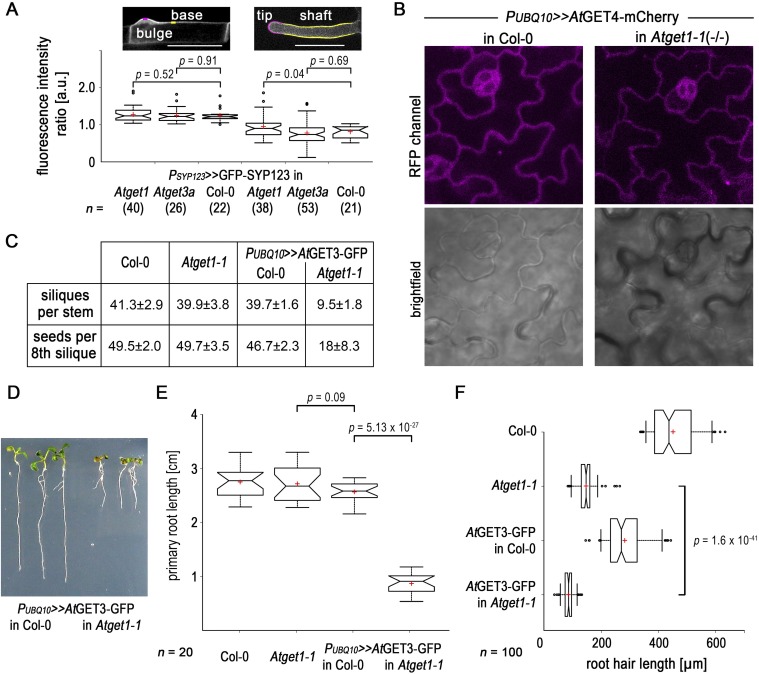

Global effects of GET pathway mutants in Arabidopsis. (A) Polarity of SYP123 expression in (Left) bulges and (Right) outgrown root hairs is not altered in WT and T-DNA insertion lines. (Inset) Microscopy pictures depict measurement of polarity ratios: mean fluorescence intensities were ratioed along the newly forming bulges (magenta) against the basal plasma membrane (yellow) or tip vs. shaft. Boxplot as in Fig. 4. Number of analyzed root hairs is in parentheses below the x axis. (Scale bars: 50 µm.) (B) Subcellular analysis of AtGET4-mCherry expressed in (Left) Col-0 and (Right) Atget1-1 revealing even cytosolic localization. (C) Siliques of main inflorescences of 20 individual lines were counted, and the eighth silique of each stem was opened and scored for aberrant seed development. The mutant plant (AtGET3a-GFP in Atget1) has significantly fewer siliques and fewer developed seeds per silique. Values are mean ± SD. An exemplary image can be found in Fig. 5C. (D–F) Additional, root growth-related phenotypes of the AtGET3a-GFP in Atget1-1–expressing plants in Fig. 5. (D) Exemplary primary roots of plants expressing AtGET3a-GFP in either (Left) WT Col-0 or (Right) Atget1-1. (E) Boxplot as in Fig. 5 showing the root length of 20 individual seedlings for each line. (F) Root hair length of the longest root hairs of 10 individual lines.

Functional Analyses of A. thaliana GET Orthologs.

Loss of function of TRC40, the GET3 ortholog in mammals, causes embryonic lethality befitting of the vital function of TA protein insertion (21). How would loss of GET pathway orthologs impact on survival, growth, and development in plants?

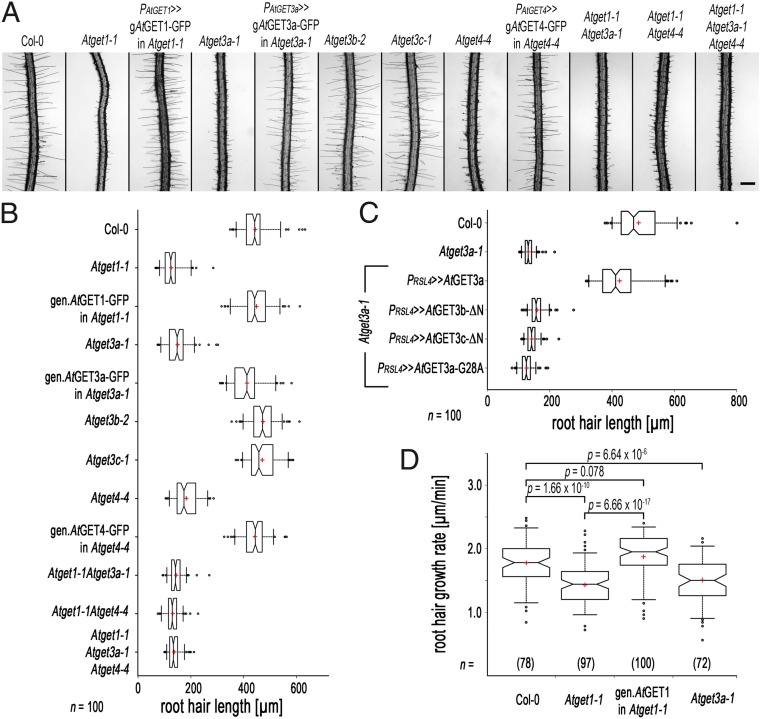

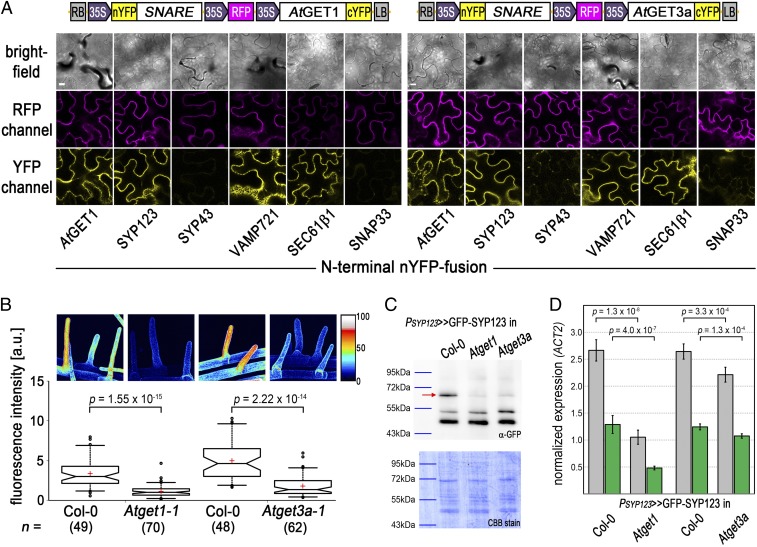

Unexpectedly, multiple different alleles of T-DNA (transfer DNA) insertion lines of each of the five AtGET orthologs identified (Fig. S4 A and B) did not reveal any obvious growth defects. Seeds germinated, and seedlings developed indistinguishable from wild-type (WT) plants. However, a more detailed phenotypic inspection revealed that seedlings of Atget1, Atget3a, and Atget4 lines had significantly shorter root hairs compared with Columbia-0 (Col-0) WT plants, whereas Atget3b and Atget3c did not (Fig. 3 A and B and Fig. S4C). Expressing genomic versions of the GET genes restores near WT-like root hair growth. By contrast, a point mutant of the P loop of the ATPase motif (AtGET3a-G28A) expressed under a root hair-specific promoter (RSL4) (39) prevents rescue in Atget3a, suggesting that ATPase activity of AtGET3a is essential for normal root hair growth (Fig. 3C). To substantiate our analysis of the AtGET3b/c paralogs, we expressed the transit peptide deletion variants in the Atget3a background. The mislocalized AtGET3b/c constructs failed to rescue the growth defects, suggesting evolution of alternative functions in the bioenergetic organelles (Fig. 3C).

Fig. S4.

Functional analysis of AtGET orthologs in planta and yeast. (A) Cartoon depicting the sequence-verified position of each T-DNA analyzed in this work (in black type font). (B) DNA gels of semi–qRT-PCR corroborate lack of transcript in all mutant lines except Atget4-1 in line with this being a T-DNA insertion in the 5′ UTR. RAN3 (At5g55190) transcript was used as control. (C) Expanded root hair growth analysis showing additional alleles and complementation thereof. Note that the 5′ UTR-inserted Atget4-1 line that still transcribes AtGET4 shows WT-like root hair growth. *Values that are also in Fig. 3. (D) Aniline blue staining of pollen tubes (the WT and Atget mutants) grown for 6 or 24 h, respectively, after pollination of Col-0 pistils. Yellow arrows point to exemplary pollen tubes termini that have reached ovules. Pictures are composites of individual images along the pistil, and exposure was enhanced to visualize the bright blue pollen tubes against the darker blue background. (E) Growth of pollen tubes was measured in vitro from 30 individual pollen grains 7 h postgermination (representative images in Right). Center lines of boxes represent medians, with outer limits at 25th and 75th percentiles. Notches indicate 95% confidence intervals; Tukey whiskers extend to 1.5× interquartile range, and red crosses mark sample means. (Scale bar: 50 µm.)

Fig. 3.

Loss of function of some A. thaliana GET orthologs causes root hair growth defects. (A) Exemplary images of root elongation zones of 10-d-old T-DNA insertion lines of A. thaliana GET orthologs and genomic complementation. Atget1-1, Atge3a-1, and Atget4-4 but not Atget3b-2 and Atget3c-1 lines show reduced growth of root hairs compared with WT Col-0 and can be complemented by their respective genomic constructs. Double or triple KOs phenocopy single T-DNA insertion lines. Transcript analysis and additional alleles can be found in Fig. S4. (B) Boxplot depicting length of the 10 longest root hairs of 10 individual roots (n = 100). Center lines of boxes represent median with outer limits at 25th and 75th percentiles. Notches indicate 95% confidence intervals; Altman whiskers extend to 5th and 95th percentiles, outliers are depicted as black dots, and red crosses mark sample means. (Scale bars: 500 µm.) (C) Boxplot as before, showing root hair length of Col-0 and Atget3a-1 and complementation thereof using a root hair-specific promoter (RSL4; At1g27740) and N-terminally 3xHA-tagged coding sequences of AtGET3a, AtGET3b-ΔN, AtGET3c-ΔN, and AtGET3a-G28Ay. (D) Boxplot as before, showing root hair growth rates of exemplary T-DNA insertion lines and complemented Atget1-1 line in micrometers per minute.

Multiple crosses between individual T-DNA insertion lines of AtGET1, AtGET3a, and AtGET4 did not yield an enhanced phenotype (i.e., further reduction of root hair length compared with their corresponding parental single-KO lines) (Fig. 3 A and B), indicating interdependent functionality of all three proteins within a joint pathway. A more detailed kinetic analysis on roots grown in RootChips (40) revealed that the shorter overall root hair length in Atget1 and Atget3a correlates with slowed down growth speed (Fig. 3D).

Root hairs together with pollen tubes are the fastest growing cells in plants and rely on efficient delivery of membrane material to the tip (41). Although we had not observed aberrant segregation ratios of T-DNA insertion lines, which could indicate compromised fertility, we analyzed pollen tube growth in vivo and in vitro but found growth speed as well as final length unaffected in the GET pathway mutants (Fig. S4 D and E).

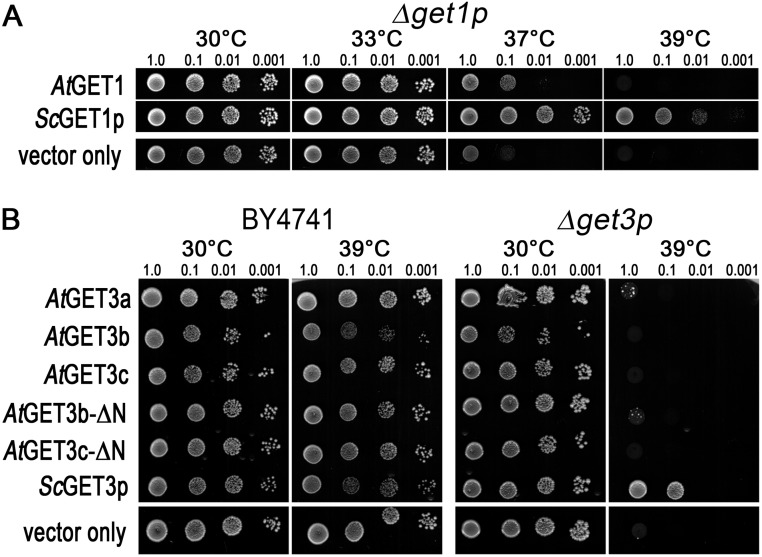

The genetic evidence for function of AtGET1 and AtGET3a in a joint pathway allowing effective root hair growth in A. thaliana prompted us to assess their functional conservation. In yeast, ScGET1 and ScGET3 are not essential; however, their absence leads to lethality under a range of different abiotic stress conditions (15). We, therefore, tested A. thaliana GET orthologs in BY4741 WT and corresponding KO strains for their ability to rescue yeast survival under restrictive conditions. AtGET1 (Fig. S5A) and to a much lesser extent, AtGET3a (Fig. S5B) hardly rescue growth in corresponding KOs, and all other AtGET3 orthologs—full length or truncated—failed to rescue at all. This result provides strong evidence that the functions of AtGET1 and AtGET3a may have diverged from yeast, more strongly so for AtGET3a.

Fig. S5.

Complementation assays of yeast KO strains with A. thaliana orthologs. (A) The yeast get1 KOs are partially rescued by the A. thaliana GET1/WRB ortholog AtGET1 (At4g16444). Yeast growth was monitored after 3 d in different growth temperatures (33 °C to 39 °C). A genomic fragment of yeast ScGET1p was used as a positive control, and an empty vector was used as a negative control. (B) Yeast WT (BY4741) or get3 KO expressing different AtGET3 orthologs and truncations thereof and grown under different temperatures. Expression of ScGET3p in the KO rescues growth under heat stress, whereas the A. thaliana ortholog AtGET3a can only partially complement the phenotype. The plastidic-localized AtGET3b and AtGET3c and their N-terminal deletion versions fail to complement.

Loss of the GET Pathway Leads to Reduced Protein Levels of SYP123 in Root Hairs.

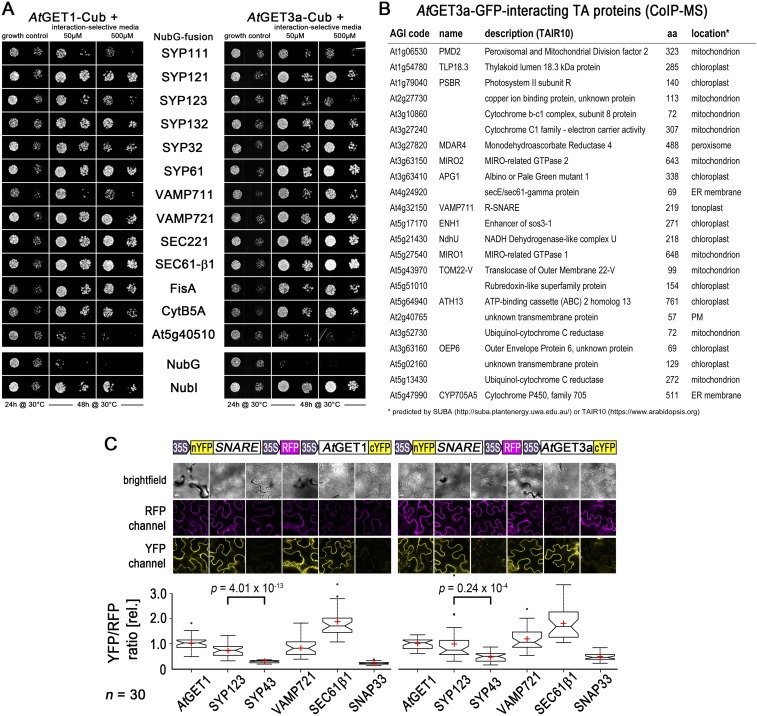

We compared the predicted “TA-proteome” of A. thaliana (13) with the list of interaction partners of AtGET3a-GFP from CoIP-MS analysis (Dataset S1). Only 23 TA proteins were detected that coprecipitated with AtGET3a-GFP but not GFP alone (Fig. S6B). However, in SUS and rBiFC analysis, AtGET3a interacts with a number of candidate TA proteins that we did not find in our CoIP-MS. Among others, the SNARE syntaxin of plants 123 (SYP123) as well as its R-SNARE partner VAMP721 and the TA protein SEC61β, subunit of the SEC61 translocon, interact with both AtGET1 and AtGET3a (Fig. 4A and Fig. S6 A and C). The SNARE SYP43 as well as the non-TA SNARE protein SNAP33 failed to interact. SYP123 is a plasma membrane-localized Qa-SNARE that specifically expresses in root hair cells, and its loss results in short root hairs (42). We crossed GFP-SYP123 under its own promoter (42) with our Atget1-1 and Atget3a-1 lines to analyze for misinsertion, mislocalization, or cytosolic retention.

Fig. S6.

Expanded information on TA–protein interactions. (A) SUS interaction analyses of candidate SNARE/TA proteins with AtGET1 and AtGET3a as Cub/bait fusion. Growth on interaction-selective media (-Ade and -His) was monitored after 2 d, and control plates were monitored after 24 h. OD600 1.0 and 0.1 dilutions were dropped, with NubG serving as negative control and NubI (WT version) serving as positive control, respectively. (B) TA proteins that were identified via CoIP-MS of AtGET3a-GFP–expressing plants that were not detected in GFP-only expressing plants. (C) Complete rBiFC analysis of (Left) AtGET1 and (Right) AtGET3a with candidate SNARE/TA proteins. Boxed cartoons show construct design above exemplary images of transiently transformed N. benthamiana leaves. Larger versions of these confocal images are in Fig. 4A. YFP/RFP mean fluorescence intensities from 30 different leaf sections were calculated and ratioed against the average YFP/RFP ratio of AtGET1 homodimerization or AtGET3a-AtGET1 interaction. Center lines of boxes represent medians, with outer limits at 25th and 75th percentiles. Notches indicate 95% confidence intervals; Tukey whiskers extend to 1.5× interquartile range, outliers are depicted as black dots, and red crosses mark sample means. (Scale bars: 10 µm.)

Fig. 4.

The root hair-specific Qa-SNARE SYP123 shows reduced protein levels in Atget lines. (A) rBiFC analysis of (Left) AtGET1 and (Right) AtGET3a with candidate SNARE/TA proteins. Boxed cartoons show construct design above representative images of epidermal cells from transiently transformed N. benthamiana leaves. The statistical analysis of the data is presented in Fig. S6C. (Scale bars: 10 µm.) (B and C) Analysis of root hairs expressing PSYP123 >> GFP-SYP123 in Atget1-1, Atget3a-1, or corresponding Col-0 WT. (B) Boxplot of root hair fluorescence intensities of average-intensity z projections (number in parentheses below the x axis). Boxplot as in Fig. 3; P values confirm a significant difference in fluorescence intensity between GFP-SYP123 expression in WT (stronger) vs. T-DNA insertion lines (weaker). Heat maps of exemplary z projections are in Upper. (C) Anti-GFP immunoblots of membrane fractions from the marker lines detect a strong GFP-SYP123 band at 62.8 kDa, which is significantly and visibly weaker in Atget3a and Atget1 lines than in WT Col-0. Bands below are likely the result of unspecific cross-reaction of antibody and plant extract. Coomassie brilliant blue staining (CBB stain) of blot confirms equal loading of protein. (D) qRT-PCR analysis of SYP123 transcript levels was performed using either SYP123- (gray) or GFP-specific (green) primers to resolve differences in mRNA levels on Col-0, Atget1, or Atget3a background. Expression levels were normalized to the Actin2 control. Error bars: SD (n = 6).

CLSM analysis of root hairs expressing SYP123 in WT and mutant backgrounds showed normal distribution of SYP123 in bulge formation and developed root hairs (Fig. S7A). No cytosolic aggregates or increased fluorescence foci were visible in the cytoplasm, which was reminiscent of findings in yeast get pathway KOs (15, 43). However, we repeatedly observed differences in GFP signal under identical conditions and settings. GFP fluorescence intensity of root hairs is consistently stronger in the WT than in Atget1 and Atget3a lines (Fig. 4B), suggestive of lower SYP123 protein levels in the plasma membrane of Atget lines.

To substantiate this finding, we performed membrane fractionation of protein extracts from roughly 250 roots per line (Fig. 4C). Immunoblot analysis revealed that GFP-SYP123 levels in the membrane fraction of Atget1 and Atget3a lines were strikingly lower than in WT background, suggesting that loss of GET pathway functionality reduces SYP123 abundance in the membrane. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analyses further indicated that SYP123 transcript levels are also reduced in both mutants compared with the WT, with a milder transcript reduction in the Atget3a than in the Atget1 background (Fig. 4D). Notably, the differences between endogenous and transgenic levels of transcript remain equal in all lines at roughly 50%, which confirms native expression of the marker construct (44) and suggests regulation of SYP123 in get lines also at transcript level.

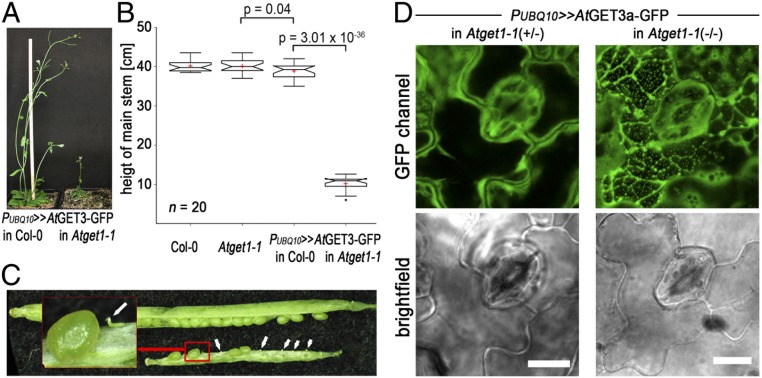

Overexpression of AtGET3a in Atget1 Reveals Severe Growth Defects.

The general viability of Atget mutants and the fact that at least part of SYP123 finds its way to the plasma membrane in root hairs of mutants question the role of the GET pathway as the sole route for TA protein insertion in A. thaliana. To further understand the physiological importance of the pathway in planta, we crossed the overexpressing AtGET3a-GFP with the Atget1-1 line. The rationale was to synthetically increase the activity of an upstream player, while limiting downstream capacity of the pathway to enhance phenotypes associated with dysfunction of the pathway. Such overexpression of the cytosolic AtGET3a in its receptor KO leads to dwarfed plants. Main inflorescence, root, silique, and seed development are severely compromised compared with the parental lines (Fig. 5 A–C and Fig. S7 C–F). In addition to the obvious aboveground phenotype, the growth of root hairs is impaired more strongly compared with the individual loss of function Atget1-1 lines (Fig. S7F). Such stronger phenotype might be a consequence of short-circuiting alternative insertion pathways, further depleting vital TA proteins from reaching their site of action.

Fig. 5.

Ectopic overexpression of AtGET3a in Atget1 causes severe growth defects. (A) Exemplary images of 6-wk-old A. thaliana plants expressing AtGET3a-GFP in either Col-0 WT or Atget1 showing significant differences in growth. (B) Boxplot summarizing the height of the main inflorescences of 20 individual 6-wk-old A. thaliana lines as labeled below the x axis. Boxplot as in Fig. 3 but with Tukey whiskers that extend to 1.5× interquartile range. (C) Siliques of mutant plants [AtGET3a-GFP in Atget1 (silique below)] show a high number of aborted embryos in contrast to single Atget1 lines (silique above). The statistical analysis can be found in Fig. S7C. (D) Maximum projection z stacks of 20 images at 1.1-µm optical slices at 63× magnification showing subcellular localization of AtGET3a-GFP in (Left) heterozygous or (Right) homozygous Atget1-1 lines. Bright-field images below are taken from the 10th image in each stack. The full z stacks are shown in Movies S1 and S2. (Scale bars: 10 µm.)

CLSM analysis of the subcellular expression of AtGET3-GFP in the leaf epidermis of homozygous Atget1 lines reveals cells with increased GFP fluorescence in foci among cells that resemble the normal cytoplasmic distribution of AtGET3a-GFP (Fig. 5D, Right and Movie S1). Conversely, no cells with GFP foci are present in leaf samples of heterozygous Atget1(+/−) lines expressing the same construct, and an even cytoplasmic distribution of AtGET3a-GFP is observable instead (Fig. 5D, Left and Movie S2). Foci may be a result of clustering of uninserted TA proteins with multimers of AtGET3a, similar to effects observed in yeast Δget1 KOs (43, 45). We have also analyzed expression of AtGET4-mCherry in an Atget1-1 background but did not detect similar aggregate-like structures (Fig. S7B).

Discussion

Numerous biochemical and structural insights from yeast and in vitro systems have convincingly established the ability of the GET pathway to facilitate membrane insertion of TA proteins (reviewed in ref. 46). However, because TRC40 KO mice are embryonic lethal, physiological consequences of GET loss of function in an in vivo context remain insufficiently understood, and those that are available are typically specific to mammalian features. Such findings are in contrast to the high degree of conservation that GET homologs show across the eukaryotic domain, a situation where the model plant A. thaliana provides a highly suitable system for additional study.

Phylogenetic analysis of GET pathway components reveals an alternative GET3 clade, which must have evolved before the last eukaryotic ancestor. This hypothesis becomes apparent from the deeply branching phylogenetic tree (Fig. 1A) but also, by the presence of a second distinct GET3 homolog in the recently discovered Lokiarchaeum sp., which forms a monophyletic group with eukaryotes (30). One of the LsGET3 copies aligns within the GET3bc clade, with sequences that seem to only exist in Archaeplastida and SAR, whereas Opisthokonts and Amoebozoa may have lost this paralog. GET3bc branched off once more in some red algae and higher plants to evolve another plastidic GET3 paralog. It is unlikely that this third paralog is the result of endosymbiosis, because its sequence homology is too closely related to the other organellar candidate.

Neither root hair nor general growth in A. thaliana seem affected by lack of AtGET3b/c, and their biological function will require dedicated study in the future. Their localization in the plastid stroma and the mitochondrial matrix; failure to interact with AtGET1, AtGET3a, or AtGET4; absence of obvious downstream candidates to facilitate membrane insertion; lack of conserved sequence motifs for TA binding (Fig. S1); and failure to complement the AtGET3a-related growth defects (Fig. 3C) deem it unlikely that AtGET3b/c function is related to TA protein insertion.

A previous structural analysis of an archaeal (Methanocaldococcus jannaschii) GET3 ortholog inferred some key features that would distinguish GET3 from its prokaryotic ArsA ancestor sequence (28), namely the tandem repeat (exclusive to ArsA) and a conserved CxxC motif (specific for GET3). By contrast, our phylogenetic analysis uncovered the tandem repeat in candidate sequences of both eukaryotic GET3 clades, disproving it as a decisive feature solely of ArsA. Such sequence repeats may explain the presence of a third closely related GET3 paralog in higher plants and red algae as a consequence of an earlier tandem duplication, but this hypothesis requires in-depth analysis of more sequences from different species.

The CxxC motif, which is found in both Metazoa and Fungi GET3 orthologs, also exists in the Amoebozoan and Lokiarchaeota GET3 orthologs and seemingly plays a role in zinc binding/coordination (19). However, this motif is absent in the Archaeplastida and SAR GET3a orthologs, where other invariant cysteines—CVC—some 40 aa upstream of the presumed CxxC motif are present. In contrast to the CxxC motif, the CVC motif can be found in all eukaryotic GET3a orthologs that we analyzed. Nevertheless, the CxxC motif is required for ScGET3 to act as a general chaperone under oxidative stress conditions, binding unfolded proteins and preventing their aggregation (43, 45). Hence, it is conceivable that GET3bc paralogs—that feature CxxC (Fig. S1B)—have evolved as organellar chaperones with putative thiol-disulfide oxidoreductase function and lost (or never had) the TA insertion capability, whereas GET3a orthologs maintained (or acquired) both functions. Notably, the chaperone function of ScGET3 is ATP-independent, whereas TA-insertase activity depends on ATP (43). A version of AtGET3a, where the ATPase motif is mutated (G28A), fails to rescue the root hair growth phenotype (Fig. 3C), suggesting that it is caused by the TA insertion function of AtGET3a, which is dependent on ATPase function (15).

Generally, T-DNA insertion in AtGET1, AtGET3a, or AtGET4 leads to a reduction in root hair growth. Complementation with tagged or genomic constructs of the corresponding genes rescues normal growth connecting phenotype with genotype. Interestingly, multiple crosses between loss of function lines of three key players of an A. thaliana GET pathway do not lead to a more severe phenotype (i.e., even shorter root hairs than the single T-DNA insertion lines as measured, e.g., in plants overexpressing AtGET3a-GFP in Atget1) (Fig. S7F). This observation indicates that the three genes act in a linear pathway in A. thaliana, which is in agreement with findings in other species (15, 16). Nevertheless, it seems difficult to reconcile our findings with a putative GET pathway as the sole and global route responsible for insertion of TA proteins in plants similar to its proposed role in yeast or mammals (46). Of the estimated 500 TA proteins in A. thaliana (13), many are vital for development and survival of the plant. Especially SNARE proteins, which facilitate vesicle fusion to drive processes, such as cytokinesis, pathogen defense, and ion homeostasis (4, 7, 47), require correct and efficient membrane insertion. Inability of the plant to insert TA proteins should yield severe growth defects at least similar to if not stronger than—for example—the knolle phenotype caused by an syp111 loss of function allele (coding for the Qa-SNARE KNOLLE). Knolle plants fail to grow beyond early seedling stage because of incomplete cell plate formation (48).

Absence of the root hair-specific Qa-SNARE SYP123 was shown to cause defects in root hair growth (42) as a result of reduced vesicle trafficking. Although lack of AtGET pathway components in planta did not lead to complete absence or mislocalization of SYP123 within the plasma membrane of root hairs, a significant reduction of protein levels was observed in vivo. Although this result was also confirmed biochemically, levels of SYP123 mRNA in Atget1 as well as Atget3a lines are also reduced (Fig. 4D), albeit not as strongly as the reduction of protein detected in the membrane fraction of mutants (Fig. 4C). Taken together, our findings indicate feedback control, where loss of AtGET function and the resulting failure of SYP123 protein insertion activate inhibition at the transcript level to decrease steady-state levels of both mRNA and protein. Functional cross-talk between the GET pathway and its impact on transcript regulation had been shown previously in other eukaryotes (23, 49).

The fact that lack of GET function can phenotypically only be detected in root hairs might be associated with these requiring fast and efficient trafficking of cargo and membrane material to the tip (42). Hence, slight imbalances in protein biogenesis owing to the absence of one major insertion pathway might strain alternative but unknown insertion systems, at which point lack of the GET pathway becomes rate-limiting. This effect is not reoccurring in the other fast-growing plant cells—pollen tubes—not only suggesting presence of an alternative pathway but also, questioning the monopoly of TA protein insertion of the GET pathway. Nevertheless, our SYP123 case study supports a role of the GET pathway in planta for regulating SNARE abundance. Interaction of AtGET1 and AtGET3a with a wide range of different TA proteins was also shown, but we identified two TA proteins that failed to interact (SYP43 and At5g40510). Also, CoIP-MS analysis of AtGET3a-GFP detected only about 23 TA proteins, less than 5% of all TA proteins predicted to be present in A. thaliana (13) (Fig. S6B). Although the latter might be attributed to weak or transient binding of the TMD with AtGET3a or premature dissolution of binding through experimental conditions, it nevertheless raises questions as to the GET pathway being exclusively engaged in TA protein insertion into the ER. Among the many proteins that were detected in CoIP-MS analysis with AtGET3a-GFP, a lot of non-TA proteins but proteins related to trafficking or proteostasis were detected (Dataset S1). If some of these interactions can be confirmed in future studies, functional analyses might uncover alternative roles for AtGET3a.

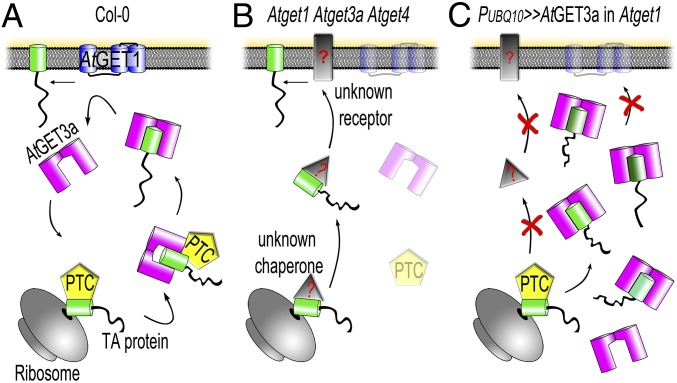

Our findings are summarized in a working model of a presumed GET pathway in plants (Fig. 6). While under normal growth conditions, the GET pathway acts as main route for TA protein insertion into the ER membrane (Fig. 6A), and loss of either component or a combination thereof brings alternative pathways into play (Fig. 6B). The existence of alternative insertion mechanisms is indicated by not only the relatively mild phenotype but also, the limited number of TA proteins that we found to interact with AtGET3a, raising the question of how TA proteins that do not interact with GET pathway components get inserted into membranes. In yeast, it has been shown that some TA proteins can insert unassisted and that chaperoning in the cytosol is facilitated by heatshock proteins (50); however, any alternative receptor remains elusive. Presence of an alternative insertion pathway in A. thaliana is also supported by the overexpression of the cytosolic AtGET3a in its receptor KO, which has severe phenotypic consequences (Figs. 5 and 6C). This observation corroborates a hierarchical connection of AtGET3a and AtGET1, because presence of the latter can rescue the growth defects. It further suggests the existence of an alternative pathway for TA insertion with weaker affinity toward pretargeting factors, such as AtGET4, at the ribosome, because the aberrant amounts of AtGET3a seem to deplete the alternative pathway. Lastly, the AtGET3a foci that can occur in cells of mutant plants (but never in the WT background) (Fig. 5D) and that are similar to aggregates observed in stressed yeast cells (43) suggest additional functions of AtGET3a that nonetheless depend on AtGET1. The aggregate-like structures were not found in all cells of mutant plants, suggesting a dosage-dependent effect (i.e., if levels of AtGET3a-GFP exceed a certain threshold, clustering occurs). Clusters may consist of multimers of AtGET3a, complexes of AtGET3a bound to TA proteins, or AtGET3a/TA proteins bound to the elusive AtGET2 receptor. In yeast, ScGET2 is the first contact point at receptor level for the ScGET3-TA protein complex before the TA protein is delivered to ScGET1 (20); hence, lack of AtGET1 could keep a putative AtGET3a/TA protein aggregate stably in the vicinity of the ER.

Fig. 6.

Model hypothesizing the subcellular mechanism of A. thaliana GET orthologs. (A) In WT Col-0, a pretargeting complex (PTC) likely comprising A. thaliana SGT2 and GET5 (both of which revealed many potential orthologs through in silico analyses) as well as the in silico-identified AtGET4, which interacts with AtGET3a in vivo, might receive nascent TA proteins from the ribosome and deliver these to the homodimer of AtGET3a, in turn shuttling the client TA protein to the ER receptor AtGET1 (an AtGET2 could not be identified through extensive BLASTp analysis and was left out of the figure). (B) The hypothetical situation in a single Atget1, Atget3a, or Atget4 or crosses thereof. In the absence of a functional GET pathway, most TA proteins are delivered by an unknown alternative pathway (depicted as a gray triangle or rectangle with red question marks). (C) Overexpression of AtGET3a in absence of a docking station to unload client TA proteins might lead to cytosolic aggregates and block of TA insertion. The affinity between the PTC and AtGET3a might be a decisive factor here, because the unknown alternative pathway does not seem to compensate for the aberrant presence of AtGET3a.

Future work on this mutant in particular will help to resolve functions of GET components in A. thaliana. A current debate about potential cross-talk between GET components in TA protein insertion and protein quality control in yeast and animal cells (51) may be further underpinned by our findings in plants, which provide the fundament to broad comparative investigations in the near future.

Materials and Methods

Plant Growth Conditions.

Seeds were grown on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog medium including 1% sugar and 0.9% plant agar, pH 5.7. Plants were cultivated in a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle at 18 °C or 23 °C in the growth chamber (SI Materials and Methods).

Construct Design.

Most constructs were designed by Gateway Recombination Reaction; vectors used for localization analyses can be found in ref. 33. A full list of oligonucleotides and constructs can be found in Tables S1 and S2 (SI Materials and Methods).

Table S1.

Oligonucleotides used for cloning and RT-PCR

| No. | 5′–3′ Sequence | Purpose |

| 83 | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTAATGGCGGCGGATTTGCCGGAGG | pDONR207-AtGET3a |

| 85 | GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGGCCACTCTTGACCCGTTCGAGTTC | pDONR207-AtGET3a |

| 104 | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGCATGGCGACTCTGTCTTCCTATCTG | pDONR207-AtGET3b |

| 106 | GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGTTTCCAAATGATATCGCCCAAGAAG | pDONR207-AtGET3b |

| 107 | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTGCATGGCGGCTTTACTTCTCCTCAATC | pDONR207-AtGET3c |

| 109 | GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGTTTCCAAATGAGATCACCCATGAAC | pDONR207-AtGET3c |

| 89 | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTAATGGAAGGAGAGAAGCTTATAGAAG | pDONR207-AtGET1 |

| 91 | GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGGAACTCCACGAACCTACACAC | pDONR207-AtGET1 |

| 86 | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTAATGTCGAGAGAGAGGATCAAACGTG | pDONR207-AtGET4 |

| 88 | GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTGGCCCATCATCTTGAAGATGTCTCC | pDONR207-AtGET4 |

| 261 | TCGGAGGTAAAGCAGGTGTTGGGAAG | Introducing G28A in AtGET3a |

| 262 | TCTTCCCAACACCTGCTTTACCTCCG | Introducing G28A in AtGET3a |

| 631 | GCGGATTTAAATAGATAAGGCTCTGTTCTTCCC | 3′ End fragment of AtGET3a |

| 632 | TGCAGATTATAACGCTTGTCACAGATACCCTTCAAC | 3′ End fragment of AtGET3a |

| 633 | TGACTGGAGCTCTTAATTAAAGGCCTATGGCGGCGGATTTGCCGGAGGCGAC | Genomic fragment of AtGET3a |

| 634 | GCACTAGTGCCACTCTTGACCCGTTCGAGTTC | A genomic fragment of AtGET3a |

| 554 | TAGTCGTTAATTAATCAGAGGAGAGAGCTAAGTGAAGGG | AtGET3a promoter |

| 553 | TTAGCCCGGGTGCTAATTCCTTGCTCGTCTCTCTTC | AtGET3a promoter |

| 625 | GCGGATTTAAATATCGCATCCCTGAAAAGAGTGAAG | 3′ End fragment of AtGET1 |

| 626 | TGCAGATTATAATAAGTACACGCGTCTTTAGAATC | 3′ End fragment of AtGET1 |

| 627 | TGACTGGAGCTCAGGCCTATGGAAGGAGAGAAGCTTATAGAAG | Genomic fragment of AtGET1 |

| 628 | GCACTAGTGAACTCCACGAACCTACACACATATTTG | Genomic fragment of AtGET1 |

| 629 | TGACTGGAGCTCGGCGCGCCTTAATTAAAGTTGGCCAAAGTAGAAAATGGTTG | AtGET1 promoter |

| 630 | GAAGGCCTTAACCCTTTTGCTGATTACTGATTC | AtGET1 promoter |

| 635 | GCGGATTTAAATGGAAGGAGTTTGAAGAGTGAGTTC | 3′ End fragment of AtGET4 |

| 636 | TGCAGATTATAAGCTCTGTAATACTTCTTGTTTCG | 3′ End fragment of AtGET4 |

| 657 | TGACTGGAGCTCAGGCCTATGTCGAGAGAGAGGATCAAACGTG | Genomic fragment of AtGET4 |

| 658 | TGCAGCTAGCGCCCATCATCTACACAGTTTCAATGG | Genomic fragment of AtGET4 |

| 659 | TGACTGGAGCTCGGCGCGCCTTAATTAACCTCTAACTATCTCTCCCTAGCTAG | AtGET4 promoter |

| 660 | GAAGGCCTGGATCTCAAGGATTTGTTGTTTTC | AtGET4 promoter |

| 442 | GTAGGCCTATTGTAAATTAACGATCTCATATTG | RSL4 promoter |

| 443 | TCACTAGTCGCTCTAACTGATCAACTCTTGCC | RSL4 promoter |

| 761 | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTAATGGCTAGCCCAACGGAGACGATTTC | AtGET3b ΔN68 |

| 762 | GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCTTAATGGCTACTCTTGCTGAAGGAGCTTC | AtGET3c ΔN50 |

| 1140 | ATGGCGGCGGATTTGCCGGAGGCG | RT-PCR for AtGET3a |

| 1141 | TCACATCTTTCAAGCCCTCAAGTC | RT-PCR for AtGET3a |

| 174 | ATAAACCCTGAGAAGGCTAGGGAAGAG | RT-PCR for AtGET3b |

| 1142 | TCAAGATTTTACCAATGGATGCATC | RT-PCR for AtGET3b |

| 177 | TGAGATCATTAGCTACTCTTGCTGAAG | RT-PCR for AtGET3c |

| 178 | TGGGAGCAGTATCAAAAACTATACGAG | RT-PCR for AtGET3c |

| 214 | TCACCGCTCAAAGATTCTCTGAAGC | RT-PCR for AtGET4 |

| 215 | TCTCGGGGTCCTCAGCTCTAACAAAATG | RT-PCR for AtGET4 |

| 1160 | AGGCAATTACTATGGAGCTTTGC | RT-PCR for AtGET4 |

| 1161 | TCTCATCCATCATAAAGTTTGCATC | RT-PCR for AtGET4 |

| 1150 | GTTAATGGAAGGAGAGAAGCTTATAG | RT-PCR for AtGET1 |

| 1151 | TACATGGCCTGTCATGTGACCTCC | RT-PCR for AtGET1 |

| 1408 | ATTGGTTTCCTCTTTTCCTCGCTCCG | RT-PCR for AtGET2 |

| 1410 | AGTGCATCCATTATCTTCTTCACC | RT-PCR for AtGET2 |

| 1546 | ATGAACGATCTTATCTCAAGCTCATTC | RT-PCR for SYP123 |

| 547 | TCAAGGTCGAAGTAGAGTGTTAAAG | RT-PCR for SYP123 |

| AGAACACCCCCATCGGCGAC | RT-PCR for GFP | |

| TGATCGCGCTTCTCGTTGGGGTC | RT-PCR for GFP | |

| GCCATCCAAGCTGTTCTCTC | RT-PCR for ACT2 | |

| CAGTAAGGTCACGTCCAGCA | RT-PCR for ACT2 |

Table S2.

Entry and destination constructs used

| Int. no. | Name | Vector | Insert | Purpose |

| e002 | pDONR207-Syp111-ST | pDONR207 | At1g08560 | Entry clone |

| e004 | pDONR207-Syp121-ST | pDONR207 | At3g11820 | Entry clone |

| e080 | pDONR207-VAMP711-ST | pDONR207 | At4g32150 | Entry clone |

| e081 | pDONR207-VAMP721-ST | pDONR207 | At1g04750 | Entry clone |

| e190 | pDONR221-L3L2-VAMP721-ST | pDONR221-P3P2 | At1g04750 | Entry clone |

| e192 | pDONR221-L3L2-SNAP33-ST | pDONR221-P3P2 | At5g61210 | Entry clone |

| E006 | pDONR207-SYP61-ST | pDONR207 | At1g28490 | Entry clone |

| E008 | pDONR207-AtGET3a-ST | pDONR207 | At1g01910 | Entry clone |

| E009 | pDONR207-AtGET3a-wo | pDONR207 | At1g01910 | Entry clone |

| E011 | pDONR207-AtGET4-wo | pDONR207 | At5g63220 | Entry clone |

| E012 | pDONR207-AtGET1-ST | pDONR207 | At4g16444 | Entry clone |

| E013 | pDONR207-AtGET1-wo | pDONR207 | At4g16444 | Entry clone |

| E014 | pDONR207-SEC221-ST | pDONR207 | At1g11890 | Entry clone |

| E101 | pDONR207-AtGET3b-ST | pDONR207 | At3g10350 | Entry clone |

| E102 | pDONR207-AtGET3b-wo | pDONR207 | At3g10350 | Entry clone |

| E103 | pDONR207-AtGET3c-ST | pDONR207 | At5g60730 | Entry clone |

| E104 | pDONR207-AtGET3c-wo | pDONR207 | At5g60730 | Entry clone |

| E105 | pDONR207-SYP32-ST | pDONR207 | At3g24350 | Entry clone |

| E107 | pDONR221-L3L2-AtSEC221-ST | pDONR221-P3P2 | At1g11890 | Entry clone |

| E108 | pDONR221-L1L4-GET3a-wo | pDONR221-P1P4 | At1g01910 | Entry clone |

| E109 | pDONR221-L1L4-GET4-wo | pDONR221-P1P4 | At5g63220 | Entry clone |

| E120 | pDONR221-L3L2-AtSYP43-ST | pDONR221-P3P2 | At3g05710 | Entry clone |

| E124 | pDONR207-ScGET3p-ST | pDONR207 | YDL100C | Entry clone |

| E126 | pDONR207-SYP123-ST | pDONR207 | At4g03330 | Entry clone |

| E128 | pDONR207-SYP132-ST | pDONR207 | At5g08080 | Entry clone |

| E143 | pDONR207-At5g40510-ST | pDONR207 | At5g40510 | Entry clone |

| E154 | pDONR221-L3L2-SYP123-ST | pDONR221-P3P2 | At4g03330 | Entry clone |

| E157 | pDONR221-L3L2-AtGET4-ST | pDONR221-P3P2 | At5g63220 | Entry clone |

| E195 | pDONR221-L3L2-AtGET1-wo | pDONR221-P3P2 | At4g16444 | Entry clone |

| E196 | pDONR221-L1L4-AtGET1-wo | pDONR221-P1P4 | At4g16444 | Entry clone |

| E198 | pDONR221-L1L4-AtGET3b-wo | pDONR221-P1P4 | At3g10350 | Entry clone |

| E199 | pDONR221-L1L4-AtGET3c-wo | pDONR221-P1P4 | At5g60730 | Entry clone |

| E221 | pDONR207-AtGET3bΔN-ST | pDONR207 | At3g10350 | Entry clone |

| E222 | pDONR207-AtGET3bΔN-wo | pDONR207 | At3g10350 | Entry clone |

| E223 | pDONR207-AtGET3cΔN-ST | pDONR207 | At5g60730 | Entry clone |

| E224 | pDONR207-AtGET3cΔN-wo | pDONR207 | At5g60730 | Entry clone |

| E243 | pDONR221-L3L2-SEC61β-ST | pDONR221-P3P2 | At2g45070 | Entry clone |

| E252 | pDONR221-L1L4-AtGET3bΔN-wo | pDONR221-P1P4 | At3g10350 | Entry clone |

| E254 | pDONR221-L1L4-AtGET3cΔN-wo | pDONR221-P1P4 | At5g60730 | Entry clone |

| E265 | pDONR221-L3L2-AtGET3a-wo | pDONR221-P3P2 | At1g01910 | Entry clone |

| E289 | pDONR207-FisA-ST | pDONR207 | At3g57090 | Entry clone |

| E374 | pDONR207-CYTb5A-ST | pDONR207 | At5g53560 | Entry clone |

| D0116 | pDRf1-AtGET1 | pDRf1-GW | E012 | Complementation |

| D0584 | pZU-LC-ScGET1p | pZU-LC | Genomic DNA | Complementation |

| D0512 | pYOX1-AtGET3a | pYOX1-Dest | E008 | Complementation |

| D0513 | pYOX1-AtGET3b | pYOX1-Dest | E101 | Complementation |

| D0514 | pYOX1-AtGET3bΔN | pYOX1-Dest | E221 | Complementation |

| D0515 | pYOX1-AtGET3cΔN | pYOX1-Dest | E223 | Complementation |

| D0516 | pYOX1-ScGET3 | pYOX1-Dest | E124 | Complementation |

| D0520 | pYOX1-AtGET3c | pYOX1-Dest | E103 | Complementation |

| D0296 | pMetYC-AtGET1 | pMetYC-Dest | E013 | SUS |

| D0076 | pMetOYC-AtGET3a | pMetOYC-Dest | E009 | SUS |

| D0078 | pNX35-AtGET3a | pNX35-Dest | E008 | SUS |

| D0086 | pNX35-AtGET3b | pNX35-Dest | E101 | SUS |

| D0088 | pNX35-AtGET3c | pNX35-Dest | E103 | SUS |

| D0298 | pXNubA22-AtGET3a | pXNubA22-Dest | E009 | SUS |

| D0299 | pXNubA22-AtGET3b | pXNubA22-Dest | E102 | SUS |

| D0300 | pXNubA22-AtGET3c | pXNubA22-Dest | E104 | SUS |

| D0297 | pXNubA22-AtGET1 | pXNubA22-Dest | E013 | SUS |

| D0081 | pNX35-SEC221 | pNX35-Dest | E014 | SUS |

| D0098 | pNX35-SYP32 | pNX35-Dest | E105 | SUS |

| d517 | pNX35-SYP121 | pNX35-Dest | e004 | SUS |

| d537 | pNX35-VAMP711 | pNX35-Dest | e080 | SUS |

| d538 | pNX35-VAMP721 | pNX35-Dest | e081 | SUS |

| D0754 | pNX35-Syp111 | pNX35-Dest | e002 | SUS |

| D0756 | pNX35-Syp61 | pNX35-Dest | E006 | SUS |

| D0786 | pNX35-SYP123 | pNX35-Dest | E126 | SUS |

| D0787 | pNX35-SYP132 | pNX35-Dest | E128 | SUS |

| D0788 | pNX35-At5g40510 | pNX35-Dest | E143 | SUS |

| D0789 | pNX35-SEC61-β1 | pNX35-Dest | E228 | SUS |

| D0790 | pNX35-CYTb5A | pNX35-Dest | E374 | SUS |

| D0791 | pNX35-FisA | pNX35-Dest | E289 | SUS |

| D0273 | pBiFCt-nYFP-AtGET4-AtGET3a-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E108 + E157 | rBiFC |

| D0356 | pBiFCt-AtGET1-nYFP-AtGET1-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-CC | E196 + E195 | rBiFC |

| D0355 | pBiFCt-AtGET1-nYFP-AtGET4-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-CC | E109 + E195 | rBiFC |

| D0354 | pBiFCt-AtGET1-nYFP-AtGET3a-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-CC | E108 + E195 | rBiFC |

| D0545 | pBiFCt-AtGET1-nYFP-AtGET3bΔN-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-CC | E252 + E195 | rBiFC |

| D0546 | pBiFCt-AtGET1-nYFP-AtGET3cΔN-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-CC | E254 + E195 | rBiFC |

| D0361 | pBiFCt-AtGET1-nYFP-AtGET3b-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-CC | E198 + E195 | rBiFC |

| D0362 | pBiFCt-AtGET1-nYFP-AtGET3c-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-CC | E199 + E195 | rBiFC |

| D0965 | pBiFCt-AtGET3a-nYFP-AtGET3a-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E108 + E265 | rBiFC |

| D0966 | pBiFCt-AtGET3a-nYFP-AtGET3bΔN-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E252 + E265 | rBiFC |

| D0973 | pBiFCt-AtGET3a-nYFP-AtGET3cΔN-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E254 + E265 | rBiFC |

| D0123 | pBiFCt-nYFP-SYP43-AtGET3a-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E108 + E120 | rBiFC |

| D0395 | pBiFCt-NC-nYFP-SYP43-ST-AtGET1-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E196 + E107 | rBiFC |

| D0980 | pBiFCt-NC-nYFP-SYP123-AtGET1-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E196 + E154 | rBiFC |

| D0267 | pBiFCt-nYFP-SYP123-AtGET3a-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E108 + E154 | rBiFC |

| D0371 | pBiFCt-NC-nYFP-VAMP721-AtGET1-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E196 + e190 | rBiFC |

| D0588 | pBiFCt-NC-nYFP-SNAP33-ST-AtGET3a-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E108 + e192 | rBiFC |

| D0589 | pBiFCt-NC-nYFP-Vamp721-ST-AtGET3a-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E108 + e190 | rBiFC |

| D0418 | pBiFCt-NC-nYFP-Ssß1-ST-AtGET1-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E196 + E243 | rBiFC |

| D0590 | pBiFCt-NC-nYFP-Ssß1-ST-AtGET3a-cYFP | pBiFCt-2in1-NC | E108 + E243 | rBiFC |

| D0090 | pUBQ10::AtGET3a-GFP | pUBQ10-GW-GFP | E009 | Localization |

| D0091 | pUBQ10::AtGET3b-GFP | pUBQ10-GW-GFP | E102 | Localization |

| D0092 | pUBQ10::AtGET3c-GFP | pUBQ10-GW-GFP | E104 | Localization |

| D0160 | pUBQ10::AtGET1-GFP | pUBQ10-GW-GFP | E013 | Localization |

| D0504 | pUBQ10::AtGET4-mCherry | pUBQ10-GW-mCherry | E011 | Localization |

| D0399 | pUBQ10::AtGET3bΔN-GFP | pUBQ10-GW-GFP | E222 | Localization |

| D0405 | pUBQ10::AtGET3cΔN-GFP | pUBQ10-GW-GFP | E224 | Localization |

ST, native stop codon; wo, without stop codon.

Interaction Analyses.

We performed rBiFC in transiently transformed tobacco according to the work in ref. 37 (SI Materials and Methods).

Microscopy.

CLSM microscopy was performed using a Leica SP8 at the following laser settings: GFP at 488-nm excitation (ex) and 490- to 520-nm emission (em); YFP at 514-nm ex and 520- to 560-nm em; and RFP/Mitotracker at 561-nm ex and 565- to 620-nm em. Chlorophyll autofluorescence was measured using the 488-nm laser line and em at 600–630 nm. TEM analysis and more details are in SI Materials and Methods.

T-DNA Lines.

The following T-DNA lines were characterized (Fig. S4 A and B): Sail_1210_E07 (Atget1-1), GK_246D06 (Atget1-2), SALK_033189 (Atget3a-1), SALK_100424 (Atget3a-2), SALK_012980 (Atget3a-3), SALK_017702 (Atget3b-2), SALK_091152 (Atget3c-1), SALK_069782 (Atget4-1), and SALK_121195 (Atget4-4). This work suggests new names for Arabidopsis thaliana genes previously termed “unknown”: AtGET1 (At4g16444), AtGET3a (At1g01910), AtGET3b (At3g10350), AtGET3c (At5g60730), and AtGET4 (At5g63220).

More details and other methods are in SI Materials and Methods.

Note Added in Proof.

During revision of this article, an analysis of conditional wrb KO mice demonstrated that the GET pathway is required for only a subset—but not all—TA proteins in vivo (67). Also, an alternative ER insertion pathway was described in yeast (68) and another study reported an ER-stress and early flowering phenotype of the Atget1-1 and Atget3a-1 lines (69).

SI Materials and Methods

In Silico and Phylogenetic Analysis.

GET pathway orthologs were identified through BLASTp search (National Center for Biotechnology Information) against proteomes of candidate species and using default settings. Multiple sequence alignments were computed using the MUSCLE algorithm with default settings of MEGA7 (52). Evolutionary history was inferred by using the maximum likelihood method based on the Whelan and Goldman + frequency mode, applying 1,000 bootstraps to validate branching. The tree with the highest log likelihood (−12,793.272) is shown. Percentages of trees above 70 in which the associated taxa clustered together are shown next to the branches. Initial trees for the heuristic search were obtained automatically by applying Neighbor-Join and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using a JTT model and then, selecting the topology with superior log-likelihood value. A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites [five categories (+G; parameter = 1.377)]. The rate variation model allowed for some sites to be evolutionarily invariable ([+I]; 4.147% sites). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 37 amino acid sequences. All positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated. That is, fewer than 5% alignment gaps, missing data, and ambiguous bases were allowed at any position. There were a total of 279 positions in the final dataset.

Construct Generation and Plant Transformation.

All PUBQ10 promoter-driven constructs were generated using Gateway technology as described previously (33). Full-length coding sequences of each gene were PCR-amplified; inserted into pDONR207, pDONR221-P1P4, or pDONR221-P3P2 via BP (ThermoFisher) reaction; and confirmed by sequencing (37). A point mutation of AtGET3a (G28A) was introduced through site-directed mutagenesis as described by ref. 53. Generation of PAtGET3a >> AtGET3a-GFP-3xHA, PAtGET1 >> AtGET1-GFP-3xHA, and PAtGET4 >> AtGET4-GFP-3xHA was done by conventional cloning from genomic DNA. The genomic fragment from start to stop codon was amplified and inserted into the binary vector PUBQ10 >> GFP-3xHA 5′ of GFP. The 3′ UTR of the respective gene was amplified as well and inserted 3′ of the 3xHA tag. After verification through sequencing, the promoter region of the gene was amplified and inserted to replace the UBQ10 promoter. These constructs were first transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 and then, dipped with WT (Col-0) plants. Oligonucleotides are listed in Table S1, and all constructs used are in Table S2.

Interaction Assays.

The mating-based SUS was applied for the detection of protein–protein interactions in yeast (36). Application of methionine decreases Cub/bait-fusion expression. The lower affinity of C-terminal NubA compared with N-terminal NubG fusions was compensated for through the use of low-methionine levels (54). All interaction assays were performed as described previously (55).

The rBiFC (37) was applied to test in planta protein–protein interaction as described previously (56). All boxplots were generated using BoxPlotR (57).

Plant Growth Conditions.

All mutant (Fig. S4 A and B) and transgenic lines are in Columbia (Col-0) background and were obtained from the Nottingham Arabidopsis Stock Centre (arabidopsis.info/). Seeds were imbibed on wet paper and stratified for 2–4 d in the dark at 4 °C before sowing on soil or surface-sterilized with chlorine gas and plated on 1/2-strength solid Murashige and Skoog medium including 1% sugar and 0.9% plant agar, pH 5.7. Plants were cultivated in a 16-h light/8-h dark cycle at 18 °C or 23 °C in the growth chamber.

Analysis of Root Hair Growth Kinetics.

Root hair growth kinetics and in part, SYP123 localization were determined on roots grown in RootChips, polydimethylsiloxane-based microfluidic perfusion devices for Arabidopsis thaliana root imaging (40). Plant cultivation on RootChips was performed as described elsewhere (58).

Image analysis of root hair growth rate was performed on bright-field time stacks in FIJI (59) as follows; time stacks of n time points were duplicated and truncated by three time points at the beginning and the end. The absolute difference between the two stacks was calculated using the FIJI image calculator tool. The resulting stack now highlighted the tip of every growing root hair as particle-like signal. The velocity of this tip representation was subsequently analyzed using the FIJI TrackMate plugin.

Root Hair, Pollen Tube Growth, and CLSM Analysis.

The roots from 10-d-old seedlings grown on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog medium plates were imaged under a light microscope (ZEISS; Axiophot) using 2.5× objective. Root hair length was measured using ImageJ. The 10 longest root hairs from 10 individual roots were examined per WT, T-DNA insertion, or complemented line.

Pollination experiments and aniline blue staining for pollen tube growth in pistils were performed as previously described (60). In vitro pollen germination was performed as reported previously (61). Pollen tubes were imaged 7 h after pollen germination on solid medium, and pollen tube length was quantified using ImageJ.

For subcellular localization of the AtGETx-GFP fusions and GFP-SYP123 in root hairs, roots of 7-d-old seedlings grown on plates or leaves from 2-wk-old plants grown in soil were observed. CLSM images were taken using a Leica SP8 CLSM. To exclude quantitative effects of the genetic background in our GFP fluorescence intensity analysis (Fig. 4B), we analyzed descendants of individual heterozygous lines. Macroscopic detection of the root hair phenotype allowed identification of homozygous get mutants, which were analyzed for mean fluorescence in root hairs as well as a similar number of randomly picked segregated lines. From at least 15 analyzed roots per line, the 5 with the strongest GFP signals were chosen for fluorescence intensity analysis. Laser settings used are given. GFP signals were measured at 488-nm ex and 490- to 520-nm em, YFP signals were measured at 514-nm ex and 520- to 560-nm em, and RFP/Mitotracker signals were measured at 561-nm ex and 565- to 620-nm em. Chlorophyll autofluorescence was measured using the 488-nm laser line and em at 600–630 nm.

Immuno-TEM.

Immunogold labeling of ultrathin thawed cryosections was performed as described previously (62). Cotyledons were fixed with 4% (vol/vol) formaldehyde followed by 8% (vol/vol) formaldehyde for 30 and 120 min, respectively. Fixed cotyledons were infiltrated with a mixture of 20% (wt/vol) polyvinylpyrrolidone and 1.8 M sucrose (63) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Ultrathin cryosections (80–100 nm) were cut with a cryoultramicrotome (UC7/FC7; Leica) at −110 °C. Thawed cryosections mounted on TEM grids were blocked with 0.2% milk powder/0.2% BSA in PBS and incubated with rabbit anti-GFP serum (1:200) for 60 min followed by several washing steps using blocking buffer. Thereafter, sections were incubated with goat anti-rabbit coupled to ultrasmall gold (Fig. 1 D and G) (1:50; Aurion) or coupled to 6-nm gold (Fig. 1J) (1:30; Dianova) for 60 min. Gold particles were silver-enhanced using R-Gent (Aurion) for 45 and 35 min. Labeled cryosections were stained with 1% aqueous uranyl acetate and embedded in methyl cellulose containing 0.45% uranyl acetate. Sections were viewed in a JEM-1400plus TEM (Jeol) at 120 kV accelerating voltage, and micrographs were recorded with a TemCam-F416 CMOS Camera (Tietz).

CoIP-MS Analysis.

Protein extracts of PUBQ10 >> AtGET3a-GFP and as control, PUBQ10 >> GFP seedlings grown under continuous light were harvested after 5 d. Three grams plant tissue was taken for the immunoprecipitation according to the work in ref. 64 with slight modifications. Only the second washing buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Triton X-100) was used, but it was used four times; 60-µL GFP-Trap Beads (ChromoTek) were added to each sample. The final precipitate in 2× Laemmli buffer was analyzed by MS at the University of Tübingen Proteome Center. Two individual biological replicates were performed, and candidates that interacted with GFP only were omitted from the final list of interaction partners (Dataset S1).

Membrane Fractionation.

Root samples (0.2–1 g) of 3-wk-old seedlings grown on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog plates (+1% sucrose + 25 µg/ml Hygromycin) were harvested and ground on ice. Samples were treated in a ratio of 1:2 with extraction buffer [1 M Tris⋅HCl, pH 7.5, 1 M MgCl2, 1 M DTT, 1/2 tablet protease inhibitor (cOmplete, EDTA-free; ROCHE), 0.5 M sucrose] and homogenized. Separation of membrane and cytosol was achieved through sequential centrifugation: 10 min at 10,000 × g and 4 °C to purify samples from cell debris followed by 1 h at 100,000 × g and 4 °C. Membrane pellets were resuspended in 50 µL fresh extraction buffer and sonicated for 5 s at 60% power, and protein concentration was measured using Bradford reagent prior immunoblotting. Protein samples were adjusted to equal concentration using Laemmli buffer [+3.5% (vol/vol) β-Mercaptoethanol] and boiled for 20 min at 65 °C.

qRT-PCR Analysis.

Total RNAs were isolated from 100 mg 5-d-old seedlings grown on 1/2 Murashige and Skoog medium by using the Isolate II RNA Plant Kit (Bioline). For cDNA synthesis, ProtoScript II–First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (NEB; 1 µg RNA) was used. qRT-PCR was performed using oligonucleotides (Table S1) specific to SYP123, GFP, and ACT2 as internal control. iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) was used and performed on the CFX96 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad). Relative quantification values were calculated using the 2−ΔCt method, with the ΔCt of ACT2 as normalization control (65).

Yeast Complementation Analysis.

A. thaliana genes for the yeast complementation analysis were expressed from a 2µ origin plasmid (pYOX1-Dest) under the strong constitutive yeast PMA1 promoter, which was based on the Gateway-compatible pDRf1-GW vector (66). Get1p and get3p KO and corresponding BY4741 WT strains were originally created by the Saccharomyces Genome Deletion Project, Stanford. Yeast was grown and transformed as described for the SUS analysis but using Uracil as selection marker. Yeast was dropped in 10 times OD dilutions on selection media and grown under different temperatures for 3 d.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Masa H. Sato for sharing the GFP-SYP123 marker line and Gabriel Schaaf for vector pDRf1-GW and yeast strains. MS analysis was done at the Proteomics Centre, University of Tübingen, and we thank Mirita Franz-Wachtel for her help in interpreting the data. We also thank Gerd Jürgens and Marja Timmermans for critical discussions and comments on the manuscript, Antje Feller and Jaquelynn Mateluna for help with the quantitative PCR analysis, and Eva Schwörzer and Laure Grefen for technical support. This work was supported by an Emmy Noether Fellowship SCHW 1719/1-1 from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; to M.S.), CellNetworks Research Group funds (to G.G.), seed funding through the Collaborative Research Council 1101 (SFB1101; to C.G.), and an Emmy Noether Fellowship GR 4251/1-1 from the DFG (to C.G.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 1762.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1619525114/-/DCSupplemental.

References