Significance

Amazonian rainforests once thought to be pristine wildernesses are increasingly known to have been inhabited by large populations before European contact. How and to what extent these societies impacted their landscape through deforestation and forest management is still controversial, particularly in the vast interfluvial uplands that have been little studied. In Brazil, the groundbreaking discovery of hundreds of geometric earthworks by modern deforestation would seem to imply that this region was also deforested to a large extent in the past, challenging the apparent vulnerability of Amazonian forests to human land use. We reconstructed environmental evidence from the geoglyph region and found that earthworks were built within man-made forests that had been previously managed for millennia. In contrast, long-term, regional-scale deforestation is strictly a modern phenomenon.

Keywords: Amazonian archaeology, Amazonian rainforest, paleoecology, pre-Columbian land use

Abstract

Over 450 pre-Columbian (pre-AD 1492) geometric ditched enclosures (“geoglyphs”) occupy ∼13,000 km2 of Acre state, Brazil, representing a key discovery of Amazonian archaeology. These huge earthworks were concealed for centuries under terra firme (upland interfluvial) rainforest, directly challenging the “pristine” status of this ecosystem and its perceived vulnerability to human impacts. We reconstruct the environmental context of geoglyph construction and the nature, extent, and legacy of associated human impacts. We show that bamboo forest dominated the region for ≥6,000 y and that only small, temporary clearings were made to build the geoglyphs; however, construction occurred within anthropogenic forest that had been actively managed for millennia. In the absence of widespread deforestation, exploitation of forest products shaped a largely forested landscape that survived intact until the late 20th century.

The notion of Amazonia as a pristine wilderness has now been overturned by increasing evidence for large, diverse, and socially complex pre-Columbian societies in many regions of the basin. The discovery of numerous, vast terra preta (anthropogenic dark earth) sites bordering the floodplains of major rivers, and extensive earthwork complexes in the seasonally flooded savannas of the Llanos de Mojos (northeast Bolivia), Marajó Island (northeast Brazil), and coastal French Guiana, are seen to represent examples of major human impacts carried out in these environments (1–10).

However, major disagreement still resides in whether interfluvial forests, which represent over 90% of Amazonian ecosystems, were settings of limited, temporary human impacts (11–13), or were instead extensively transformed by humans over the course of millennia (14–16). A paucity of paleoecological studies conducted in interfluvial areas has been responsible for the polarization of this debate, which encompasses different hypothetical estimates of precontact population size and carrying capacity in the interfluves (17), and the relative importance of different land use strategies in the past. The extent of ancient forest burning is particularly contested, because some have proposed that pre-Columbian deforestation was on a large enough scale to have influenced the carbon cycle and global climate (18, 19), whereas others argue that large-scale slash-and-burn agriculture is a largely postcontact phenomenon (20). Modern indigenous groups often subject slash-and-burn plots for crop cultivation to long fallow periods, during which useful plants, including many tree species, continue to be encouraged and managed in different stages of succession within a mosaic-type landscape (21, 22). Also known as “agroforestry,” this type of land use is thought to have been common in pre-Columbian times, but its detection in the paleoecological record is often problematic (15) and studies based on modern distributions of useful species lack demonstrable time depth of forest modifications (23). Terrestrial paleoecology programs are essential for a better understanding of these issues, which have strong implications for the resilience of Amazonian forests to human impact and, subsequently, their future conservation (24–26).

With ditches up to 11 m wide, 4 m deep, and 100–300 m in diameter, and with some sites having up to six enclosures, the geoglyphs of western Amazonia rival the most impressive examples of pre-Columbian monumental architecture anywhere in the Americas (27). Excavations of the geoglyphs have shown that they were built and used sporadically as ceremonial and public gathering sites between 2000 and 650 calibrated years before present (BP), but that some may have been constructed as early as 3500–3000 BP (28–30). Evidence for their ceremonial function is based on an almost complete absence of cultural material found within the enclosed areas, which suggests they were kept ritually “clean,” alongside their highly formalized architectural forms (mainly circles and squares)—features that distinguish the geoglyphs from similar ditched enclosures in northeast Bolivia (5, 31). Surprisingly, little is known about who the geoglyph builders were and how and where they lived, as contemporary settlement sites have not yet been found in the region. It is thought that the geoglyph builders were a complex network of local, relatively autonomous groups connected by a shared and highly developed ideological system (32). Although some have proposed a connection between the geoglyphs and Arawak-speaking societies (33), the ceramics uncovered from these sites defy a close connection with Saladoid–Barrancoid styles normally associated with this language family, and instead present a complex mixture of distinct local traditions (34). Furthermore, it is likely that the geoglyphs were used and reused by different culture groups throughout their life spans (29).

As archaeological evidence points to interfluvial populations in Acre on such an impressive scale, understanding the nature and extent of the landscape transformations that they carried out is vital to how we perceive Amazonian forests in the present and conserve them in the future. Crucially, if the region’s forests were intensively cleared for geoglyph construction and use, this might imply that terra firme forests are more resilient to human impacts than previously thought.

Paleolimnology is unsuited to tackle these questions. Most geoglyphs are situated away from lakes, which generally occupy abandoned river channels too young to capture the full temporal span of pre-Columbian occupation. Instead, we applied phytolith, charcoal, and stable carbon isotope analyses to radiocarbon-dated soil profiles at two excavated and dated geoglyph sites: Jaco Sá (JS) (9°57′38.96″S, 67°29′51.39″W) and Fazenda Colorada (FC) (9°52′35.53″S, 67°32′4.59″W) (Fig. 1; SI Text, Site Descriptions) to reconstruct vegetation and land use before, during, and after geoglyph construction (SI Text, Terrestrial Paleoecology Methods).

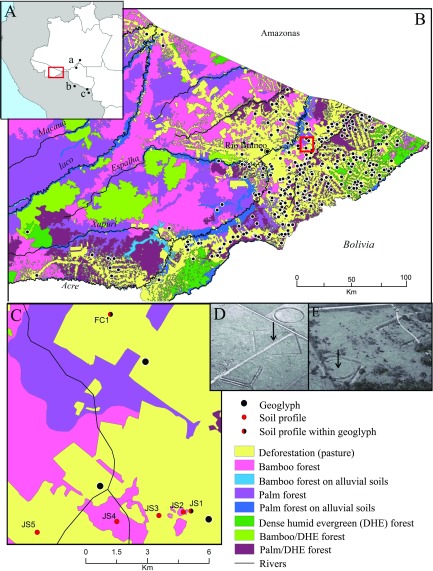

Fig. 1.

Location maps. (A) Location of eastern Acre (Inset) and paleoecological studies that document a savanna–rainforest transition in the mid-Holocene: (a) soil profiles between Porto Velho and Humaitá (stable carbon isotopes), (b) Lagunas Orícore and Granja (pollen), and (c) Lagunas Bella Vista and Chaplin (pollen). (B) Geoglyph distributions in relation to modern vegetation and location of FC and JS sites (Inset). (C) Locations of soil profiles in this study. From the JS geoglyph (0 km), profile distances along the transect are as follows: JS2 = 0.5 km, JS3 = 1.5 km, JS4 = 3.5 km, and JS5 = 7.5 km. (D and E) Aerial photos of the FC (D) and JS (E) geoglyphs. Black arrows show the locations of profiles FC1 and JS1.

We aimed to answer the following questions: (i) What was the regional vegetation when the geoglyphs were constructed? Today, the region is dominated by bamboo (Guadua sp.) forests (Fig. 1B), which cover roughly 161,500 km2 of southwest Amazonia (35). Was bamboo forest also dominant before the geoglyphs, as some have suggested (36–38)? Or did people exploit and maintain a more open landscape afforded by dryer climatic conditions of the mid-Holocene (8000–4000 BP) (39), as recently found to be the case for pre-Columbian earthworks <1,000 y old in the forest–savanna ecotone of northeast Bolivia (26, 40)? (ii) What was the extent of environmental impact associated with geoglyph construction? If the study area was forested, was clearance effected on a local (i.e., site-level) or regional (i.e., more than several kilometers) scale, and how long were openings maintained? (iii) How was the landscape transformed for subsistence purposes (e.g., through burning or agroforestry)? (iv) What happened to the vegetation once the geoglyphs were abandoned? Did previously cleared areas undergo forest regeneration?

SI Text

Site Descriptions.

Fazenda Colorada consists of three earthworks: a circle, a square, and a double U-shape. The U-shape encloses several small mounds and a trapezoidal enclosure, from which a road emanates and disappears into the terrain after 600 m. Radiocarbon dates from the site place its construction and use between 1925–1608 BP and 1275–1081 BP. Dating of one of the mounds inside the U-shape revealed that that this structure belongs to a later occupation, dated to 706–572 BP. This date represents the most recent cultural activity so far associated with the geoglyph culture (29).

Jaco Sá consists of a square earthwork, a circle within a square, and a rectangular embankment between the two. Artifact recovery during excavation was minimal and restricted to the ditch structures. Dates from the external embankment of the square/circle and the single square place their construction as contemporary (1174–985 and 1220–988 BP, respectively). A slightly earlier date of 1405–1300 BP from ceramic residue is interpreted as a preearthwork occupation episode (29).

JK Phytoliths.

In 2010, a pilot phytolith study was carried out at the JK geoglyph (9°43′57.3″ S, 67°03′41.7″ W), which consists of a square, double-ditched earthwork with slightly rounded corners and a causeway-like feature emanating from its northern side. Two units were excavated: one in the center of the geoglyph (U1), which yielded almost no archaeological material, and one at the bottom of the southern inner ditch (U2), which contained higher quantities of ceramics and charcoal until ∼200 cm below surface (BS). Dates obtained from this inner ditch place geoglyph construction between ∼1866–1417 cal y BP (28). At U1, soil samples were analyzed from the surface (0–2 and 2–5 cm) and then every 5 cm until 30 cm BS. At U2, samples were analyzed from the surface (0–5 cm), and then roughly every 30–40 cm of the profile until 180 cm BS.

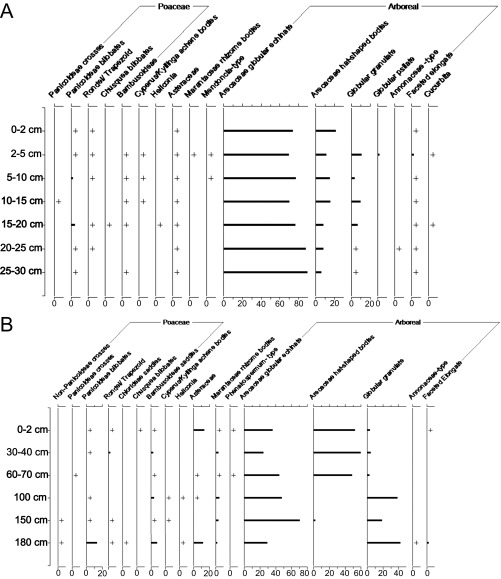

Fig. S1A shows how palms (Arecaceae) completely dominate phytolith assemblages from U1, with samples containing between 70–90% globular echinates and 5–20% hat-shaped bodies (SI Methods, Phytolith Methods). Phytoliths from domesticated squash (Cucurbita sp.) were identified in the 2- to 5- and 15- to 20-cm samples. The rest of the phytolith assemblages consisted of arboreal types and trace amounts (<2%) of Panicoideae grasses, bamboo, and other herbs (e.g., Cyperus sp., Heliconia sp., Asteraceae, Marantaceae).

Fig. S1.

Relative frequency diagram of phytoliths from the JK geoglyph site. (A) Excavation unit U1 located in the center of the geoglyph. (B) Excavation unit U2 located at the bottom of one of the inner ditches. “+” represents quantities <2%.

Phytoliths from U2, the ditch unit, were also dominated by palms and other arboreal types (Fig. S1B). A change in forest composition around 100 cm BS is implied by the disappearance of hat-shaped palm phytoliths [produced by Bactris and Astrocaryum genera (59)] and an increase in arboreal globular granulate phytoliths. The timing of this transition occurred at some point during the use of the geoglyph, because the original ditch base was reached at ∼200-cm BS. Squash phytoliths were not recovered, and the herbaceous component was very similar to U1.

These results, although preliminary in nature, are sufficient to imply the presence of pre-Columbian palm-dominated forest at the JK geoglyph. As phytolith sampling was not extended below 30 cm at U1, we cannot estimate its antiquity. Its presence is also attested to in the U1 surface samples, perhaps hinting that this vegetation persisted until deforestation of the site in 2005.

Terrestrial Paleoecology Methods.

Phytoliths.

Phytoliths are opal silica bodies produced in the leaves, stems, inflorescences, and roots of plants, and their 3D morphologies are specific to the plant taxa that produce them (55). Studies comparing phytolith assemblages produced by modern forest analogs in southwest Amazonia (50, 56) have demonstrated their effectiveness in distinguishing different vegetation types, whereas their high taxonomic resolution within early successional herbs (ESHs) (11), such as grasses and Heliconia, permit the identification of past forest disturbance events within the paleoecological record (11, 55).

Phytoliths were advantageous to this study for two reasons. Unlike pollen, they survive well in terrestrial soils—including the weathered, acidic ultisols of eastern Acre—and the majority of geoglyph sites are situated in the interfluvial uplands away from lakes and rivers. Second, phytoliths are released into the soil where the host plant dies. Controlling for topography (i.e., not sampling on slopes or depressions where phytoliths may have arrived by colluvial transport), phytoliths from a soil profile provide a highly local representation of vegetation history at that location (55). This allows the identification of vegetation heterogeneity across horizontal space, important in identifying spatial scales of past landscape transformations.

Charcoal.

Quantification of soil charcoal is a common means of detecting past fire occurrence. Because fire was a widely used management tool in pre-Columbian Amazonia (20), it was deemed an essential proxy in our study.

Studies into charcoal deposition show that particles larger than 100–125 µm (macroscopic charcoal) are more likely to have arrived from local to extralocal fire events rather than having been transported over long distances (57, 60). Furthermore, particles measuring >250 µm are considered as representative of in situ burning (61). We chose to quantify charcoal from two size classes (125–250 and >250 µm) to distinguish extralocal vs. more local burning and thus aid interpretation. Although charcoal recovery was low throughout the profiles, the presence of charcoal “peaks,” particularly in the larger fraction, was interpreted as evidence of singular burning episodes, and were targeted for AMS dating.

Stable carbon isotopes.

In soil profiles, analysis of δ13C values of carbon preserved within soil organic matter (SOM) may be used to indicate the ratio of C3:C4 plants that persisted in an environment and contributed to pedogenesis during the past (62). Soils from tropical savannas, which contain many grasses that use a C4 photosynthetic pathway, typically have δ13C values (relative to Vienna PDB) between −19.5‰ and −16‰, whereas in forested sites, where the vegetation is typically C3, values range between −30‰ and −22.5‰ (63).

Stable carbon isotope analysis was conducted on soils from JS1 (sampled every 10 cm) and JS3 (sampled every 10 cm, then every 20 cm below 0.4 m below surface), to provide an indicator of the dominant vegetation types present before, during, and following construction of the geoglyphs to provide information pertaining to the vegetation in the vicinity of the Jaco Sá geoglyph and its changes over time.

Charcoal and soil humin dates.

Charcoal for dating was extracted in bulk from the soil samples to provide an average soil horizon age and minimize problems with dating singular fragments that may have been translocated in the profile. Dating efforts focused on specific events recorded in the phytolith and charcoal records, in particular charcoal peaks that represented anthropogenic burning activity and the beginning of the decline in palm taxa (FC1, JS2, JS2, and JS4).

Basal dates for the profiles (all but JS1) were retrieved by 14C dating of soil humin [benzene/liquid scintillation counting at Centro de Energia Nuclear na Agricultura (CENA) laboratories (64)] due to the lack of charcoal in these lower strata. Soil humin is considered the most stable component of SOM and provides more reliable dates for organic matter formation than bulk dates. A study comparing 14C ages of humin, bulk SOM, and charcoal in soil profiles from central Brazil found that humin and charcoal ages were in good agreement up to 1.0–1.5 m BS, whereas bulk SOM dates were significantly younger in the same horizons (65).

In the FC1 profile, an initial charcoal date from the 50- to 55-cm horizon (the beginning of a charcoal peak expected to relate to geoglyph construction) demonstrated an older source for charcoal than expected for its vertical depth (see below). An additional soil humin sample was subsequently obtained from the 45- to 50-cm horizon (the charcoal peak maxima), which yielded a date much more in accordance with the archaeological date for geoglyph construction.

Age Inversions.

Charcoal age inversions (where younger charcoal appeared below older charcoal) occurred in four of the profiles (all but JS2 and JS5). This was not surprising, given other studies that report the same phenomenon in Amazonian soils (66, 67), but it did call into question the extent to which our proxy data could be trusted to represent a chronological series of events.

The integrity of each soil profile stratigraphy was judged qualitatively based on the available proxy data. Specifically, it was hypothesized that the profile data were broadly representative if:

i) Patterns observed in one profile were repeated in other profiles at similar depths.

Profiles with the strongest shared patterns are FC1 and JS1, which record initial peaks in charcoal, followed by a gradual, uninterrupted increase in palm taxa. In both profiles, palms continue to increase through a second charcoal peak and then suddenly decline further up in the sequence. The pattern of gradual palm increase and sudden decline is also repeated at JS2 at similar depths, whereas at JS4, a related pattern can be observed after 60–65 cm where a swell in palm abundance accompanies a general increase in burning activity at the locale.

JS3 is relatively poorly dated but shares some patterns with other profiles. Like at FC1 and JS5, there is a relative increase in bamboo and grasses at the expense of arboreal taxa in the top half of the profile, whereas δ13C values of SOM reflect those from JS1, remaining fairly stable until the top 10–20 cm, when the signal is enriched due to the influence of modern C4 grass cover. JS3 was deemed to be most disturbed of all of the soil profiles.

ii) The proxy data were in accordance with one another.

Throughout the profiles, the phytolith and charcoal data correspond well with one another, that is, peaks in local (>250-µm) charcoal are accompanied by peaks in ESHs and/or a dip in bamboo phytoliths in the same horizons. Such sharp, temporary fluctuations in the proxy data would not be expected if the stratigraphies had undergone significant mixing, because bioturbation has the effect of homogenizing soil horizons. A recent study of phytoliths from surales (earthworm mounds) in the Colombian llanos found stratigraphic and horizontal diversity in phytolith assemblages to be extremely low due to the soil-mixing activities carried out by these ecosystem engineers (68). In our study, fluctuations in local charcoal, grass, and bamboo frequencies mirror one another at JS1, JS4, and JS5, which in turn correspond well with δ13C values from JS1 and JS3.

iii) Events dated in the soil profiles were consistent with archaeological dates.

Dates for the first charcoal peaks at FC1 and JS1, after which extralocal (<125 µm) charcoal becomes overall more abundant, correspond well with archaeological data that demonstrate an increase in regional population around 4000 BP (28). The second charcoal peak at FC1 was dated by associated soil humin to 2158–2333 BP, only some 200 y before archaeological dates for geoglyph construction and use. Although dated charcoal from the horizon below (50–55 cm) shows the inclusion of older charcoal in this portion of the profile, the pattern of a sharp dip in bamboo and a peak in larger charcoal at 45–50 cm is most parsimoniously related to geoglyph construction. At JS1, a direct date of the second charcoal peak (1385–1530 BP) is in agreement with archaeological dates of 1300–1405 BP for a (supposedly preearthwork) cultural level at the site, and roughly 100 y earlier than the archaeological dates for earthwork construction (between 985 and 1220 BP).

Dates from levels that contain peak palm phytolith percentages at FC1 and JS1 (20–25 cm) again demonstrated an older source for the associated charcoal than would be expected at these depths (6485–6651 and 2357–2698 BP, respectively). However, charcoal associated with the same event at JS2 and JS4 (10–15 cm) yielded agreeing dates of 546–652 and 659–688 BP, which coincide with archaeological dates for geoglyph abandonment. It was therefore much more likely that the palm decline observed in FC1 and JS1 were part of the same phenomenon.

Causes of Age Inversions.

From the strength of shared patterns in the FC1 and JS1 profiles, the presence of charcoal over 6,000 y old at 50-cm BS at FC1 cannot be explained by significant bioturbation within the soil in the profile. One possibility is that older charcoal was deposited on the ground surface during earthwork construction; however, one might also expect this to show in the phytolith record—instead, the pattern of increasing palms is maintained, mirroring the situation at JS1 and JS2. The same is true of the charcoal date at 20–25 cm at JS1, although here the redeposited charcoal was not so ancient (2357–2698 BP). At JS2 (80–85 cm) and JS5 (100–105 cm), charcoal dates were older than the basal soil humin dates. Because soil humin dates represent the minimum age of SOM (65), these disparities may have been caused by the downward movement of organic matter from the surface. At JS4, the charcoal date of 2955–3157 BP at 10–15 cm could be an effect of bioturbation, because a similar date was retrieved for charcoal at 50–55 cm. Alternatively, burning of older vegetation may have contributed older charcoal to the profile. Inverted but roughly contemporaneous dates from JS3 (30–35 and 60–65 cm) could also be the result of bioturbation.

Study Area

The study area is characterized by seasonal precipitation (average, 1,944 mm/y), the majority of which falls between October and April (41). The eastern part of the state where the geoglyphs are located can experience severe drought during its 4- to 5-mo dry season and has been subject to several recent wildfires, partly exacerbated by the loss of roughly 50% of the region’s forest to cattle ranching since the 1970s (42). The local vegetation is dominated by bamboo forest with patches of palm forest, grading into dense humid evergreen forest closer to the southern border with Bolivia (43) (Fig. 1A). Soils of the region are sandy clay acrisols, a relatively fertile type of ultisol that still has low agricultural potential (44). More fertile alluvial soils are found only along the region’s three major rivers—the Purus, Juruá, and Acre.

Typical of most geoglyphs, JS and FC are situated on topographical high points (191 and 196 m above sea level), within a landscape of gently rolling hills belonging to the Solimões geological formation. We excavated five soil profiles (JS1–JS5) along a linear transect starting at the center of the JS geoglyph (JS1) and at distances of 0.5, 1.5, 3.5, and 7.5 km (JS5) away from the site (Fig. 1C). This sample design allowed quantification of the spatial scale of environmental impact associated with geoglyph construction and use, ranging from highly localized (<0.5-km radius) to regional (>7.5-km radius). An additional soil profile was placed inside the FC geoglyph, situated 10 km away from JS, to compare the context of earthwork construction at that site. All of the soil profiles were located within pasture dominated by nonnative grasses and palm trees (mostly Attalea sp., Mauritia flexuosa, and Euterpe precatoria), except for JS4, which lay within bamboo forest.

Results and Discussion

Exploiting Bamboo Forest.

Basal dates from the soil profiles range from 6500 BP (JS5) to 4500 BP (JS3) (Table S1). Phytolith assemblages dominated by bamboo bulliform phytoliths in the sand fraction (SI Methods) and >15% bamboo short cells in the silt fraction (Fig. 2; SI Methods, Phytolith Methods), demonstrate that the bamboo forest ecosystem that exists in the region today was present throughout the past ∼6,000 y. These data provide compelling empirical evidence that the dominance of bamboo in this region is not a legacy of pre-Columbian human impact but is instead a natural phenomenon reflecting the distinctive climate and topography of the region. They also demonstrate the resilience of this forest ecosystem to the drier-than-present climatic conditions of the mid-Holocene (∼6000 BP), a period exemplified by a major lowstand of Lake Titicaca (45) and a shift from forest to savanna in northeast Bolivia and neighboring Rondônia state, Brazil (46–48) (Fig. 1A, a, b, and c).

Table S1.

List of radiocarbon dates obtained in the study

| Profile | Depth, cm | Lab no. | Material | C14 age years BP, ±2σ error | Cal age BP |

| FC1 | 20–25 | Beta-377101 | Charcoal | 5760 ± 30 | 6485–6651 |

| FC1 | 45–50 | CENA-959 | Humin | 2240 ± 20 | 2158–2333 |

| FC1 | 50–55 | Beta-377102 | Charcoal | 5300 ± 30 | 6186–8084 |

| FC1 | 100–105 | Beta-377103 | Charcoal | 3390 ± 30 | 3569–3701 |

| FC1 | 140–145 | CENA-960 | Humin | 4800 ± 20 | 5476–5594 |

| JS1 | 20–25 | OxA-29507 | Charcoal | 2432 ± 25 | 2375–2698 |

| JS1 | 30–35 | Beta-355557 | Charcoal | 1560 ± 30 | 1385–1530 |

| JS1 | 80–85 | Beta-355558 | Charcoal | 3690 ± 30 | 3927–4146 |

| JS1 | 140–145 | OxA-29506 | Charcoal | 5230 ± 29 | 5918–6174 |

| JS2 | 10–15 | OxA-29510 | Charcoal | 605 ± 23 | 546–652 |

| JS2 | 50–55 | OxA-29509 | Charcoal | 3728 ± 27 | 3986–4152 |

| JS2 | 80–85 | OxA-29508 | Charcoal | 6984 ± 33 | 7720–9334 |

| JS2 | 140–145 | CENA-961 | Humin | 5780 ± 20 | 6501–6650 |

| JS3 | 10–15 | OxA-29512 | Charcoal | AD 1958 | Modern |

| JS3 | 30–35 | OxA-29511 | Charcoal | 2694 ± 26 | 2756–2850 |

| JS3 | 60–65 | OxA-29694 | Charcoal | 2344 ± 30 | 2319–2460 |

| JS3 | 115–120 | CENA-962 | Humin | 3940± 20 | 4295–4500 |

| JS4 | 10–15 | OxA-29466 | Charcoal | 708 ± 25 | 569–688 |

| JS4 | 20–25 | OxA-296465 | Charcoal | 2901 ± 28 | 2955–3157 |

| JS4 | 50–55 | OxA-29513 | Charcoal | 2487 ± 25 | 2471–2722 |

| JS4 | 140–145 | CENA-963 | Humin | 4090 ± 20 | 4455–4800 |

| JS5 | 20–25 | OxA-29469 | Charcoal | 1783 ± 25 | 1618–1812 |

| JS5 | 60–65 | OxA-29468 | Charcoal | 4350 ± 50 | 4836–5212 |

| JS5 | 100–105 | OxA-29467 | Charcoal | 5731 ± 32 | 6446–6635 |

| JS5 | 140–145 | CENA-964 | Humin | 5700 ± 30 | 6406–6599 |

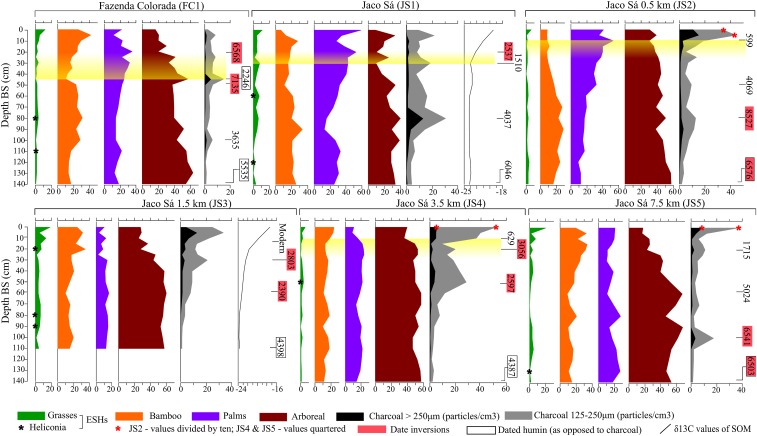

Fig. 2.

Percentage phytolith frequencies, charcoal concentrations, δ13C values (expressed in per mille) and midrange 14C dates (in calibrated years before present, 2σ accuracy) by depth for the six soil profiles. Shaded yellow bars delimit levels pertaining to geoglyph use. Geoglyph construction is represented at FC1 (45–50 cm) and JS1 (30–35 cm) by dates that are in rough agreement with archaeological dates for these events (FC: 1925–1608 BP; JS: 1220–985 or 1405–1300 BP). The abandonment of the geoglyph landscape (dated archaeologically to ∼706–572 BP) is represented by 14C dates for palm phytolith decline at JS2 and JS4 (10–15 cm), which can be extrapolated to FC1 and JS1 where this phenomenon also occurred, but where the intrusion of older charcoal hindered direct dating of these events (SI Text and SI Methods for more information).

The phytolith assemblages continue to record bamboo forest in the late Holocene (after ∼4000 BP), during which increases in smaller (125–250 µm) charcoal particles demonstrate intensification of forest clearance and/or management by humans. Wetter-than-previous climatic conditions characterized the late Holocene (39), which would have made the vegetation less naturally flammable, whereas archaeological dates attest to people in the landscape from at least 4400 BP (28); thus, we can be confident that fire activity in these levels was human—rather than naturally—driven. It is likely that these cultures took advantage of the bamboo life cycle to facilitate deforestation (36), as Guadua bamboo undergoes periodic mass die-offs every 27–28 y across areas averaging 330 km2 (35). The resulting dead vegetation is flammable in the dry season, which favors clearance using fire, rather than laborious tree felling with stone axes. The recovery of maize (Zea mays) and squash (Cucurbita sp.) phytoliths at the Tequinho and JK geoglyph sites (49) (SI Text, JK Phytoliths) suggests that clearance was related to agricultural practices, as well as the creation of dwelling spaces.

Geoglyph Construction.

Surprisingly, despite the relative ease with which bamboo forest could be cleared, we found no evidence that sizeable clearings were created for any significant length of time (i.e., over multidecadal to centennial timescales) for geoglyph construction and use. Charcoal peaks at FC1 (45–50 cm) and JS1 (30–35 cm), with 2σ date ranges (respectively, 1385–1530 BP from charcoal and 2158–2333 BP from associated soil humin) that agree with archaeological dates for site construction, represent initial earthwork building at both locations; however, true grass (nonbamboo) phytoliths remain below 10%, as opposed to ∼40–60%, which would be expected if open, herbaceous vegetation was subsequently maintained (50). Furthermore, δ13C values of soil organic matter (SOM) at JS1 (30–25 cm) remain between −23‰ and −24‰, attesting to the persistence of predominantly C3 (closed-canopy) vegetation during this time. Given that peak values of 20% for grass phytoliths and −19.7‰ for δ13C in surface samples (0–5 cm) represent 40-y postdeforestation, we deduce that the vegetation was never kept completely open for this length of time in the pre-Columbian era. This finding is consistent with archaeological evidence that the geoglyphs were used on a sporadic basis rather than continually inhabited (28, 29). Furthermore, the absence of a charcoal peak or abrupt vegetation change 500 m away (JS2) implies that forest clearance for geoglyph construction was highly localized. This suggests that the geoglyphs were not designed for intervisibility, but were instead hidden from view: an unexpected conclusion.

Rather than being built within largely “untouched” bamboo forest, our phytolith data suggest that the geoglyphs were constructed within anthropogenic forests that had already been fundamentally altered by human activities over thousands of years. At FC1 and JS1, pregeoglyph forest clearance events dated to ∼3600 and ∼4000 BP, respectively, were followed by remarkably consistent increases in palm taxa (+28% at FC1, +30% at JS1) that continued for ∼3,000 y, throughout the period of construction and use of the geoglyph sites. The same trend is observed at JS2 (+25%) after a small charcoal peak contemporary to that at JS1 (∼4000 BP), whereas a rise in palm abundance (+8%) at JS4 also follows increased fire activity (∼2600 BP), although the pattern is less pronounced than in the other three profiles.

No natural explanation exists for this increase in palms, because a wetter late Holocene climate (45) would have discouraged their colonization as the canopy became denser. Instead, palm increase correlates with an overall increase in human land use, documented by the charcoal data. Preliminary data gathered in 2011 from a soil profile within the JK geoglyph (SI Text, JK Phytoliths; Fig. S1) further documented up to 90% palm phytoliths at 30-cm depth, suggesting that many of Acre’s geoglyphs were constructed within similar palm-rich forests. Because >450 geoglyph sites have been discovered in eastern Acre, this implies anthropogenic forest transformation over a large area of the interfluvial uplands.

The long-term concentration of palm species in the past was likely both intentional and unintentional, given their high economic importance for food and construction material (51, 52) and the very long timescales over which they appear to have proliferated. We suggest a positive-feedback mechanism for this trend, whereby pre-Columbian groups initially cleared and occupied these locations and manipulated forest composition (marked by the first charcoal peaks), and the subsequent concentration of useful species later attracted other groups to the same locations, who in turn encouraged them further.

Legacies of Anthropogenic Forests.

What happened once the geoglyphs were abandoned ∼650 BP? Toward the top of the profiles, a sudden decrease in palm taxa [between −15% (JS4) and −25% (JS1)] occurs at all four locations where they have proliferated. Dated charcoal from these levels gave erroneous dates at FC1 and JS1 (SI Text, Age Inversions); however, concordant dates from JS2 and JS4 (∼600–670 BP) associate the beginning of the palm decline with the period of geoglyph abandonment, suggesting a link between these two phenomena.

Such a scenario finds support in studies of forest succession. In the Amazonian terra firme, palms are often the first trees to colonize forest clearings after herbs and lianas (53) but are eventually outcompeted by slower-growing trees (54). If humans stopped maintaining this artificial succession stage, palm communities would eventually be replaced by other species. The sudden resurgence of palms observed in the 0- to 5-cm horizons is explicable by the same mechanism, as modern deforestation has favored their colonization by creating completely open landscapes.

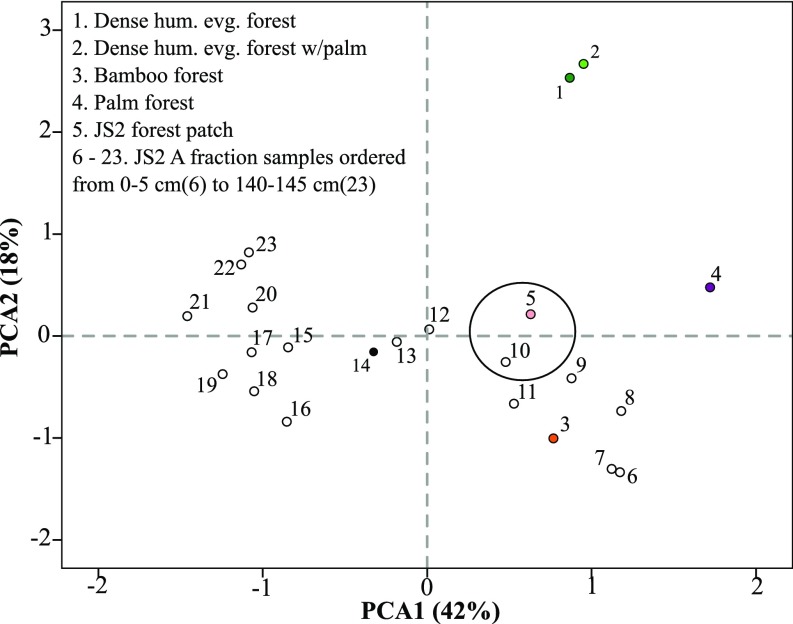

Instead of reverting back to a more “natural” state, however, other evidence suggests that the species that outcompeted palms after geoglyph abandonment were already managed alongside them. A botanical inventory of a residual forest patch adjacent to the JS2 profile found that 9 out of 10 of its most abundant species are of current socioeconomic importance (SI Methods, JS2 Forest Patch Methods; Table S2). However, several of these species do not produce diagnostic phytoliths [e.g., Bertholettia excelsa (Brazil nut)], or produce them rarely (e.g., Tetragastris altissima). Furthermore, in a principal-components analysis, average surface-soil phytolith assemblages from this forest patch plotted close to phytolith sample 20–25 cm in the JS2 profile (Fig. S2), immediately below the peak in palm phytoliths, implying that legacies of pre-Columbian agroforestry still exist today within Acre’s remaining forests.

Table S2.

Relative frequencies of the 10 most abundant species and families recorded in JS2 forest patch

| Most common tree species, % | Most common tree families, % | ||

| Tetragastris altissima (Burseraceae)* | COMM | Burseraceae | COMM |

| Bertholettia excelsa (Lecythidaceae)* | 15.2 | Arecaceae | 28.6 |

| Euterpe precatoria (Arecaceae)* | 11.2 | Fabaceae | 12.7 |

| Jacaranda copaia (Bignoniaceae)* | 7.9 | Lecythidaceae | 10.0 |

| Astrocaryum murumuru (Arecaceae)* | 5.6 | Bignoniaceae | 9.1 |

| Astrocaryum tucuma (Arecaceae)* | 5.6 | Moraceae | 7.7 |

| Bellucia, sp. (Melastomataceae) | 3.9 | Melastomataceae | 4.1 |

| Maclura tinctora (Moraceae)* | 3.9 | Euphorbiaceae | 3.2 |

| Cedrela odorata (Meliaceae)* | 3.9 | Meliaceae | 3.2 |

| Bactris coccinea (Areaceae)* | 3.2 | Urticaceae | 3.2 |

| Total | 57.3 | Total | 78.6 |

COMM, community.

Useful species.

Fig. S2.

Plotted factor scores from a PCA of averaged phytolith frequencies from the JS2 forest patch, modern vegetation analogs, and paleoecological samples from the JS2 profile. The phytolith assemblage from sample 10 (20–25 cm) plots closely with that of the JS2 forest patch.

SI Methods

Field and Laboratory Sampling.

Profiles were excavated to a depth of 1.5 m and soil sampled every 5 cm for phytoliths, charcoal, and stable carbon isotopes. At JS3, profile excavation had to be halted at 1.2 m due to the presence of large, dense laterite concretions, making this profile shorter than the other five.

Samples were initially analyzed for phytoliths and charcoal every 10 cm before sending charcoal for AMS dating. Once the horizons relating to geoglyph construction were ascertained (above 50–55 cm for FC1 and 30–35 cm for JS1), resolution was increased to every 5 cm from these horizons to the surface.

Phytolith Methods.

Phytoliths were extracted from soils following standard protocols (55). Each soil sample was wet-sieved into a silt (<53 µm) and a sand (53–250 µm) fraction to better aid interpretations of paleovegetation (50, 56), producing two datasets per soil horizon. Given the dominance of bamboo bulliform phytoliths recovered in the sand fractions (up to 90%), relative frequencies of silt fraction phytoliths (Fig. 1) were deemed to provide a more sensitive reflection of paleovegetation.

To aid data interpretation, morphotypes were grouped into four categories—ESH phytoliths [grasses (Poaceae) and Heliconia] (sensu ref. 11), bamboo (Bambusoideae), palms (Arecaceae), and arboreal—once phytolith counts were completed (200 per slide). The grass category is represented by bilobate and saddle short cells belonging to the Panicoideae (C4) and Chloridoideae (C3 and C4) grasses (69, 70), respectively. Bamboo phytoliths consisted mainly of tall/collapsed and “blocky” saddle types, spiked rondels, and chusquoid bodies (70), all of which are produced by Guadua (C3), the monodominant bamboo in southwest Amazonian bamboo forests. Rondel phytoliths were excluded from categorization, as they are produced both by true grasses and bamboos. Palms produce either hat-shaped or globular echinate phytoliths and are prolific phytolith producers, although identifications to genus level are not yet possible (55). Arboreal taxa were represented largely by globular phytoliths possessing granulate or smooth surface decoration, which are produced in the wood and bark of many tropical tree families (71, 72) and are excellent indicators of past forest cover (73). Other arboreal forms identified included tracheary elements (tracheids and sclereids), faceted phytoliths, and vesicular infillings (74, 75).

Bamboo Forest and Vegetation Analogs.

To assign phytolith assemblages from the soil profiles to vegetation types, surface soil phytoliths were analyzed from five different modern forest formations in Acre (bamboo, palm, fluvial, dense humid evergreen, and dense humid evergreen with abundant palm) (56). All forest formations were able to be statistically separated by phytolith relative frequencies after applying principal-components analysis (PCA), apart from the dense humid evergreen types, which clustered together.

Bamboo forest was able to be distinguished from other formations on account of bamboo short-cell phytoliths (>10%) in the silt fraction and the dominance of bamboo bulliform phytoliths in the sand fraction (56). As both these conditions were met in the soil profile phytolith assemblages, we could be confident that this forest formation was present at all soil profile locations since the beginning of the records.

Charcoal Methods.

Charcoal was extracted from 3 cm3 of soil using a modified macroscopic sieving method (57), and each fraction was counted for charcoal in a gridded Petri dish with a binocular loop microscope. Many of the samples contained black mineral particles that looked similar to charcoal, so pressure was applied with a glass rod to see if they fragmented when identification was uncertain. Absolute charcoal abundances were transferred into charcoal volume (particles per cubic centimeter) upon analysis.

Stable Carbon Isotope Methods.

As a comparative exercise, four surface soil samples (n = 3) from three of the modern vegetation analogs sampled for phytoliths (bamboo, palm, and dense humid evergreen forest) were also analyzed, which yielded averaged δ13C values of −28.4‰, −28.5‰, and −26.3‰, respectively (n = 3).

It was noted that the δ13C values from the profiles where bamboo forest vegetation was recorded were isotopically enriched relative to those from the modern bamboo forest surface soils. At JS1, values ranged between −23.9‰ and −24.3‰ where phytoliths recorded nondisturbed bamboo forest (100–140 cm), and between −23.2‰ and −23.8‰ at JS3 (90–110 cm). Such disparity may be explained by δ13C enrichment from modern vegetation or the high rates of organic matter decompositions in the profile soils, which can lead to δ13C enrichment of up to 4‰ (76).

δ13C and total organic carbon values for the soils were obtained using standard procedures (58). Special care was taken to avoid the inclusion of rootlets and similar nonrepresentative materials in each sample. Analytic precision was typically 0.1‰ (σn-1, n = 10).

Charcoal and Soil Humin Dating.

AMS dating was performed on 19 charcoal samples (Beta and OxA laboratories) from the soil profiles and calibrated to 2σ accuracy using IntCal13 calibration curve (77) (Table S1). Northern hemisphere calibration was used because the study area falls within the seasonal migration of the Intertropical Convergence Zone, which introduces northern hemispheric 14C signals to these lower latitudes (78).

JS2 Forest Patch Methods.

An opportunistic botanical inventory of the forest patch adjacent to the JS2 profile recorded all species >10-cm diameter at breast height along a 50-m transect. A total of 61 species (n = 220) was noted and the 10 most abundant are presented in Table S2. Three surface soil samples, representing the top 2–3 cm of topsoil once leaf litter was removed, were collected at random points within the inventoried area and analyzed for phytoliths. The phytolith assemblages were then averaged and fed into a PCA alongside averaged phytolith assemblages from the modern vegetation analogs and the JS2 soil profile samples. Resulting factor scores were plotted graphically, and revealed a similarity in phytolith assemblages from the modern-day forest patch and the 20- to 25-cm horizon at JS2 (Fig. S2).

Implications

In contrast to studies that argue for either minimal (11, 12) or widespread (15, 16) pre-Columbian impact on the Amazonian interfluves, we suggest that, in Acre, geoglyph construction was not associated with deforestation over large spatial and temporal scales but instead with a long tradition of agroforestry and resource management that altered the composition of native bamboo forest over millennia.

Our findings challenge the hypothesis that reforestation after the Columbian encounter led to a sequestration of CO2 that triggered the Little Ice Age global cooling event (18, 19). This hypothesis was formerly criticized in light of findings that many earthworks in northeast Bolivia were constructed in nonforested landscapes (26), but our data indicate that, even in an archaeologically rich area that remained forested during the mid- to late Holocene, pre-Columbian deforestation was on a more localized scale than previously thought. Despite the number and density of geoglyphs, we did not find any pre-Columbian parallel for the length and extent of modern-day forest clearance in Acre.

Our data also raise a methodological concern crucial to the interpretation of terrestrial paleoecological data—namely, that low soil charcoal frequencies do not necessarily correlate with sparse pre-Columbian populations in Amazonia (11). There is little question that the geoglyphs are a product of sizeable, socially complex societies that once inhabited the region (27, 32), so the absence of evidence of large-scale deforestation in our soil profiles casts doubt over whether quantification of forest burning should play such a central role in delimiting areas of high vs. low populations, and minimal vs. widespread environmental impacts associated with them.

In contrast, our study has provided empirical, paleoecological evidence for the importance of forest management practices in the pre-Columbian interfluves. The proliferation of palms and other useful species over apparently millennial timescales suggests a long history of forest manipulation before the JS and FC geoglyphs were even constructed, consistent with some arguments that long-term accumulations of small-scale disturbances can fundamentally alter species composition (15, 16).

We did not detect anthropogenic forest in all profile locations but recognize that formations not rich in palms are currently very difficult to detect in the phytolith record. This point is made clear by the species and phytolith data from the JS2 forest plot, which hint at the other species that were favored by pre-Columbian populations (e.g., Brazil nut) that do not produce diagnostic phytoliths.

We have shown that at least some of Acre’s surviving forest owes its composition to sustainable pre-Columbian forest management practices that, combined with short-term, localized deforestation, maintained a largely forested landscape until the mid-20th century. The lack of a pre-Columbian analog for extensive modern deforestation means that we should not assume forest resilience to this type of land use, nor its recovery in the future.

Methods

Soil profiles were dug to 1.5-m depth and sampled in 5-cm increments for paleoecological analyses. Chronologies were based upon four accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) dates per soil profile, the majority being determined on bulk macroscopic (>125 µm) charcoal (19 samples), and the remainder on soil humin (6 samples) (Table S1). Due to the occurrence of age inversions, the integrity of the proxy data was assessed based on interprofile replicability of observed patterns (e.g., increases in palm phytoliths) and obtained dates consistent with geoglyph chronologies (SI Text, Age Inversions). Phytoliths were extracted every 5 cm in levels pertaining to geoglyph use and every 10 cm thereafter, following the wet oxidation method (55). Two hundred morphotypes were identified per soil sample, and taxa were identified using published atlases and the University of Exeter phytolith reference collection. Paleoecological phytolith assemblages were compared with assemblages from surface soils of modern forests in the region (56). Charcoal was extracted using a macroscopic sieving method (57) and divided into size classes to distinguish local (>250 µm) from extralocal (125–250 µm) burning signals. Stable carbon isotope analysis of SOM was conducted at JS1 (every 10 cm) and JS3 (every 10 cm, then every 20 cm below 0.4 m below surface) using standard procedures (58). Detailed information for the methodologies used in this study is provided in SI Methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Whitney, M. Arroyo-Kalin, Y. Maezumi, M. Power, J. Carson, and T. Hermenegildo for their insights during the course of the project, J. Gregorio de Souza for creating Fig. 1, and F. Braga for fieldwork support. Funding for this research was granted by the United Kingdom Arts and Humanities Research Council (AH/J500173/1) (to J.W.), Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) (NE/B501504) (to N.J.L.), NERC/OxCal Radiocarbon Fund (2013/2/8) (to J.W and J.I.), and National Geographic Society and Exploration Europe (GEFNE14-11) (to F.E.M. and J.I.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1614359114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Denevan WM. The pristine myth: The landscape of the Americas in 1492. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 1992;82(3):369–385. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neves EG, Petersen JB. Time and Complexity in Historical Ecology. Columbia Univ Press; New York: 2006. Political economy and pre-Columbian landscape transformations in Central Amazonia; pp. 279–309. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heckenberger M, Neves EG. Amazonian archaeology. Annu Rev Anthropol. 2009;38(1):251–266. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMichael CH, et al. Predicting pre-Columbian anthropogenic soils in Amazonia. Proc Biol Sci. 2014;281(1777):20132475. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Denevan WM. 1966 The Aboriginal Cultural Geography of the Llanos de Mojos of Bolivia. Ibero-Americana 48 (University of California Press, Berkeley, CA) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erickson CL. The domesticated landscapes of the Bolivian Amazon. In: Erickson CL, Balée W, editors. Time and Complexity in Historical Ecology. Columbia Univ Press; New York: 2006. pp. 235–278. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erickson CL. The Lake Titicaca basin: A pre-Columbian built landscape. In: Lentz D, editor. Imperfect Balance: Landscape Transformations in the Pre-Columbian Americas. Columbia Univ Press; New York: 2000. pp. 311–356. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaan D. The non-agricultural chiefdoms of Marajó Island. In: Silverman H, Isbell WH, editors. Handbook of South American Archaeology. Springer; New York: 2008. pp. 339–357. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rostain S. Pre-Columbian earthworks in coastal Amazonia. Diversity (Basel) 2010;2(3):331–352. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iriarte J, et al. Late Holocene neotropical agricultural landscapes: Phytolith and stable carbon isotope analysis of raised fields from French Guianan coastal savannahs. J Archaeol Sci. 2010;37(12):2984–2994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McMichael CH, et al. Sparse pre-Columbian human habitation in western Amazonia. Science. 2012;336(6087):1429–1431. doi: 10.1126/science.1219982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piperno DR, McMichael C, Bush MB. Amazonia and the Anthropocene: What was the spatial extent and intensity of human landscape modification in the Amazon Basin at the end of prehistory? Holocene. 2015;25(10):1588–1597. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bush MB, et al. Anthropogenic influence on Amazonian forests in pre-history: An ecological perspective. J Biogeogr. 2015;42(12):2277–2288. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roosevelt AC. The Amazon and the Anthropocene: 13,000 years of human influence in a tropical rainforest. Anthropocene. 2014;4:69–87. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clement CR, et al. The domestication of Amazonia before European conquest. Proc Biol Sci. 2015;282(1812):20150813. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.0813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stahl PW. Interpreting interfluvial landscape transformations in the pre-Columbian Amazon. Holocene. 2015;25(10):1598–1603. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denevan WM. Estimating Amazonian Indian numbers in 1492. J Lat Am Geogr. 2014;13(2):207–221. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nevle RJ, Bird DK. Effects of syn-pandemic fire reduction and reforestation in the tropical Americas on atmospheric CO2 during European conquest. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2008;264(1-2):25–38. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dull RA, et al. The Columbian Encounter and the Little Ice Age: Abrupt land use change, fire, and greenhouse forcing. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2010;100(4):37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arroyo-Kalin M. Slash-burn-and-churn: Landscape history and crop cultivation in pre-Columbian Amazonia. Quat Int. 2012;249:4–18. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Posey A, Balée W. Resource Management in Amazonia: Indigenous Folk Strategies. New York Botanical Garden; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clement CR. Demand for classes of traditional agroecological knowledge in modern Amazonia. In: Posey DA, Balick MJ, editors. Human Impacts on Amazonia: The Role of Traditional Ecological Knowledge in Conservation and Development. Columbia Univ Press; New York: 2006. pp. 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clement CR, et al. Response to comment by McMichael, Piperno and Bush. Proc Biol Sci. 2015;282(1821):20152459. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.2459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heckenberger MJ, Russell JC, Toney JR, Schmidt MJ. The legacy of cultural landscapes in the Brazilian Amazon: Implications for biodiversity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2007;362(1478):197–208. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bush MB, Silman MR. Amazonian exploitation revisited: Ecological asymmetry and the policy pendulum. Front Ecol Environ. 2007;5(9):457–465. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carson JF, et al. Environmental impact of geometric earthwork construction in pre-Columbian Amazonia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(29):10497–10502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321770111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaan D. Sacred Geographies of Ancient Amazonia: Historical Ecology of Social Complexity. Left Coast Press; San Francisco: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saunaluoma S, Schaan D. Monumentality in western Amazonian formative societies: Geometric ditched enclosures in the Brazilian state of Acre. Antiqua. 2012;2:e1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schaan D, et al. New radiometric dates for precolumbian (2000–700 B.P.) earthworks in western Amazonia, Brazil. J Field Archaeol. 2012;37(2):132–142. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pärssinen M, Schaan D, Ranzi A. Pre-Columbian geometric earthworks in the upper Purus: A complex society in western Amazonia. Antiquity. 2009;83(322):1084–1095. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Prümers H. Sitios prehispánicos com zanjas en Bella Vista, Provincia Iténez, Bolivia. In: Rostain S, editor. Antes de Orellana. Actas Del 3er Encuentro Internacional de Arqueología Amazônica. IFEA; FLASCO; MCCTH; SENESCYT; Quito, Ecuador: 2014. pp. 73–91. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saunaluoma S, Virtanen PK. Variable models for organization of earthworking communities in Upper Purus, southwestern Amazonia: Archaeological and ethnographic perspectives. Tipití J Soc Anthropol Lowl South Am. 2015;13(1):23–43. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eriksen L. 2011. Nature and culture in prehistoric Amazonia. PhD dissertation (Lund University, Lund, Sweden)

- 34.Saunaluoma S. Cerâmicas do Acre. In: Barreto C, Lima HP, Betancourt CJ, editors. Cerâmicas Arqueológicas Da Amazônia: Rumo a Uma Nova Síntese. IPHAN: Ministério de Cultura, Belém; PA, Brazil: 2016. pp. 414–419. [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Carvalho AL, et al. Bamboo-dominated forests of the southwest Amazon: Detection, spatial extent, life cycle length and flowering waves. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54852. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McMichael CH, Palace MW, Golightly M. Bamboo-dominated forests and pre-Columbian earthwork formations in south-western Amazonia. J Biogeogr. 2014;41(9):1733–1745. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMichael CH, et al. Historical fire and bamboo dynamics in western Amazonia. J Biogeogr. 2013;40(3):299–309. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olivier J, et al. First macrofossil evidence of a pre-Holocene thorny bamboo cf. Guadua (Poaceae: Bambusoideae: Bambuseae: Guaduinae) in south-western Amazonia (Madre de Dios–Peru) Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 2009;153:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayle FE, Power MJ. Impact of a drier Early-Mid-Holocene climate upon Amazonian forests. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363(1498):1829–1838. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carson JF, et al. Pre-Columbian land use in the ring-ditch region of the Bolivian Amazon. Holocene. 2015;25(8):1285–1300. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duarte AF. Variabilidade e tendência das chuvas em Rio Branco, Acre, Brasil. Rev Bras Meteorol. 2005;20:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aragão LEOC, et al. Interactions between rainfall, deforestation and fires during recent years in the Brazilian Amazonia. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2008;363(1498):1779–1785. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.0026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Daly DC, Silveira M. First Catalogue of the Flora of Acre. Universidade Federal do Acre; Rio Branco, Brazil: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quesada CA, et al. Soils of Amazonia with particular reference to the RAINFOR sites. Biogeosciences. 2011;8(6):1415–1440. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker PA, et al. The history of South American tropical precipitation for the past 25,000 years. Science. 2001;291(5504):640–3. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5504.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mayle FE, Burbridge R, Killeen TJ. Millennial-scale dynamics of southern Amazonian rain forests. Science. 2000;290(5500):2291–2294. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5500.2291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pessenda LCR, et al. Origin and dynamics of soil organic matter and vegetation changes during the Holocene in a forest-savanna transition zone, Brazilian Amazon region. Holocene. 2001;11(2):250–254. [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Freitas HA, et al. Late Quaternary vegetation dynamics in the southern Amazon basin inferred from carbon isotopes in soil organic matter. Quat Res. 2001;55(1):39–46. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Watling J, Saunaluoma S, Pärssinen M, Schaan D. Subsistence practices among earthwork builders: Phytolith evidence from archaeological sites in the southwest Amazonian interfluves. J Archaeol Sci Reports. 2015;4:541–551. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dickau R, et al. Differentiation of neotropical ecosystems by modern soil phytolith assemblages and its implications for palaeoenvironmental and archaeological reconstructions. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 2013;193:15–37. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Clement CR. 1492 and the loss of Amazonian crop genetic resources. I: The relation between domestication and human population decline. Econ Bot. 1999;53(2):188–202. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kahn F. Ecology of economically important palms in Amazonia. Adv Econ Bot. 1988;6:42–49. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kahn F, Granville JJ. Ecological Studies. Vol 95. Springer; Berlin: 1992. Palms in forest ecosystems of Amazonia; pp. 41–89. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Salm R, Jalles-filho E, Schuck-paim C. A model for the importance of large arborescent palms in the dynamics of seasonally-dry Amazonian forests. Biota Neotropica. 2005;5(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Piperno DR. Phytoliths: A Comprehensive Guide for Archaeologists and Paleoecologists. Altimira; Oxford, UK: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Watling J, et al. Differentiation of neotropical ecosystems by modern soil phytoliths assemblages and its implications for palaeoenvironmental and archaeological reconstructions. II: Southwestern Amazonian forests. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 2016;226:30–43. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Whitlock C, Larsen C. Charcoal as a fire proxy. In: Smol JP, Birks HJB, Last WM, editors. Tracking Environmental Change Using Lake Sediments, Volume 3: Terrestrial, Algal and Siliceous Indicators. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht; The Netherlands: 2001. pp. 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Metcalfe SE, et al. Hydrology and climatology at Laguna La Gaiba, lowland Bolivia: Complex responses to climatic forcings over the last 25,000 years. J Quat Sci. 2014;29(3):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morcote-Ríos G, Bernal R, Raz L. Phytoliths as a tool for archaeobotanical, palaeobotanical and palaeoecological studies in Amazonian palms. Bot J Linn Soc. 2016;182(2):348–360. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Clark JS. Particle motion and the theory of charcoal analysis: Source area, transport, deposition and sampling. Quat Res. 1988;30:67–80. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gardner JJ, Whitlock C. Charcoal accumulation following a recent fire in the Cascade Range, northwestern USA, and its relevance for fire-history studies. Holocene. 2001;11(5):541–549. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kelly E, et al. Stable isotope composition of soil organic matter and phytoliths as paleoenvironmental indicators. Geoderma. 1998;82(1-3):59–81. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pessenda LCR, et al. The carbon isotope record in soils along a forest-cerrado ecosystem transect: Implications for vegetation changes in the Rondonia state, southwestern Brazilian Amazon region. Holocene. 1998;8(5):599–603. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pessenda LCR, Camargo PB. Datação radiocarbônica de amostras de interesse arqueológico e geológico por espectrometria de cintilação líquida de baixa radiação de fundo. Quim Nova. 1991;2:98–103. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pessenda LCR, Gouveia SEM, Aravena R. Radiocarbon dating of total soil organic matter and humin fraction and its comparison with 14C ages of fossil charcoal. Radiocarbon. 2001;43(2B):595–601. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Soubiès F. Existence d’une phase sèche en Amazonie Brésilienne datée par la présence de charbons dans les sols (6.000-8.000 ans B.P.) Cah ORSTOM Ser Geol. 1979;9(1):133–146. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Piperno DR, Becker P. Vegetational history of a site in the central Amazon basin derived from phytolith and charcoal records from natural soils. Quat Res. 1996;45(2):202–209. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zangerlé A, et al. The Surales, self-organized earth-mound landscapes made by earthworms in a seasonal tropical wetland. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0154269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Twiss PC, Suess E, Smith RM. Morphological classifications of grass phytoliths. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1969;33(1):109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Piperno DR, Pearsall DM. The silica bodies of tropical American grasses: Morphology, taxonomy, and implications for grass systematics and fossil phytolith identification. Smithson Contrib Bot. 1998;85:1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Geis JW. Biogenic silica in selected species of deciduous angiosperms. Soil Sci. 1973;116:113–130. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilding LP, Drees LR. Contributions of forest opal and associated crystalline phases to fine silt and clay fractions of soils. Clays Clay Miner. 1974;22:295–306. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bremond L, Alexandre A, Hely C, Guiot J. A phytolith index as a proxy of tree cover density in tropical areas: Calibration with leaf area index along a forest-savanna transect in southeastern Cameroon. Global Planet Change. 2005;45(4):277–293. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Runge F. The opal phytolith inventory of soils in central Africa—quantities, shapes, classification, and spectra. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1999;107(1-2):23–53. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Strömberg CE. Using phytolith assemblages to reconstruct the origin and spread of grass-dominated habitats in the great plains of North America during the late Eocene to early Miocene. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2004;207(3-4):239–275. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sanaiotti ATM, et al. Past vegetation changes in Amazon savannas determined using carbon isotopes of soil organic matter. Biotropica. 2002;34(1):2–16. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Reimer PJ, et al. IntCal13 and Marine13 radiocarbon age calibration curves, 0–50,000 years cal BP. Radiocarbon. 2013;55(4):1869–1887. [Google Scholar]

- 78.McCormac FG, et al. SHCal04 Southern hemisphere calibration, 0–11.0 cal kyr BP. Radiocarbon. 2004;46(3):1087–1092. [Google Scholar]