Significance

Heart disease is the primary cause of death in the United States. Cardiac tissue engineering has evolved with the goal of creating heart patches to treat end-stage patients. Here, we report on a bottom-up approach to assemble a modular cardiac patch that consists of various tissue layers, each performing a different function. One layer was designed to accommodate cardiac cells and promote their organization into a contracting tissue. Another layer enables the organization of endothelial cells into blood vessels, and layers with microparticulate systems enable the controlled release of different biofactors affecting the engineered tissue or the host. We have shown that the patch can be assembled from its building blocks just before transplantation and can perform in the body.

Keywords: cardiac tissue engineering, electrospinning, laser patterning, vascularization, controlled release

Abstract

In cardiac tissue engineering cells are seeded within porous biomaterial scaffolds to create functional cardiac patches. Here, we report on a bottom-up approach to assemble a modular tissue consisting of multiple layers with distinct structures and functions. Albumin electrospun fiber scaffolds were laser-patterned to create microgrooves for engineering aligned cardiac tissues exhibiting anisotropic electrical signal propagation. Microchannels were patterned within the scaffolds and seeded with endothelial cells to form closed lumens. Moreover, cage-like structures were patterned within the scaffolds and accommodated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microparticulate systems that controlled the release of VEGF, which promotes vascularization, or dexamethasone, an anti-inflammatory agent. The structure, morphology, and function of each layer were characterized, and the tissue layers were grown separately in their optimal conditions. Before transplantation the tissue and microparticulate layers were integrated by an ECM-based biological glue to form thick 3D cardiac patches. Finally, the patches were transplanted in rats, and their vascularization was assessed. Because of the simple modularity of this approach, we believe that it could be used in the future to assemble other multicellular, thick, 3D, functional tissues.

Heart tissue engineering evolved with the aim of replacing damaged myocardium with a cardiac patch with structural and functional properties resembling the native tissue (1–3). The myocardium has a complex 3D architecture composed of a cellular component and an intricate fibrous network of the structural extracellular matrix (ECM) (4). Each layer of these fibers guides cell organization to form anisotropic sheets of myocardial syncytia that are responsible for directional contractions (5, 6). A slight shift in the alignment of adjacent layers ensures a circular contraction and leads to a strong pump function (6). To support the high metabolic demand of the contracting tissue, a dense vascular network between several cell layers provides oxygen and nutrients to the surrounding cells. Because heart muscle function is highly dependent on this unique structural organization, recapitulating both its anisotropic geometry throughout the ventricle wall and the internal vasculature is pivotal for engineering functional cardiac tissues that can be used in regenerative applications (7).

Numerous approaches have been used to recapitulate different structural properties of the heart (7–11). Technologies such as lithography and microfabrication enabled precise control over the biomaterial pattern and thus over the induced cell alignment and anisotropic electrical signal transfer (8, 12). However, using these techniques for engineering thick 3D tissues with multicellular layers is still a challenge. On the other hand, macroporous scaffolds and hydrogels are suitable for engineering thick 3D tissues, but with these scaffolds the different tissue layers cannot be controlled separately (13–16). Thus, the cells throughout the entire scaffold are exposed to the same culture conditions, topography, and biochemical content, and different tissue compartments cannot be engineered separately. For example, because cardiac cells and blood vessel cells require different culture medium and distinct ECM structure and composition, and mature at different time points, engineering spatially controlled vasculature within a cardiac patch may be a challenge (17, 18). To overcome these challenges, recent advances in lithographic methods have enabled the layer-by-layer assembly of anisotropic 3D cardiac tissues and a vascular compartment embedded within them (19–21). For example, Zhang and colleagues (21) have reported on the production of a biodegradable scaffold with a built-in vasculature. In a different study Ye and colleagues (20) reported the stacking of elastomeric microvessels and heart cell scaffolds to form 3D vascularized tissues. However, the scaffolds used to create the layers do not recapitulate the fibrous nature of the cardiac ECM, which is essential for tissue maturation.

Electrospinning is a well-established method used in tissue engineering to fabricate fibrous scaffolds (9, 10, 22–24). We have recently reported on the potential of albumin fiber scaffolds to promote the assembly of anisotropic and functional cardiac patches. However, their relatively low thickness (∼100 µm) may limit their clinical applicability (24). Here, we propose to overcome these challenges by a bottom-up design approach in which each layer of the engineered tissue has a distinct role. Electrospun fibrous layers were laser-patterned to create distinct, predefined architectures to support cardiac cells or blood vessel-forming cells. The patterned scaffolds had three distinct architectures: (i) microgrooves to promote the assembly of aligned cardiac tissues, (ii) microtunnels with side cages to accommodate endothelial cells and microparticles that slowly release VEGF, respectively, and (iii) microcage-like structures for the entrapment of poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) microparticles that control the release of anti-inflammatory drugs into the exterior microenvironment (Fig. 1). Each individual layer was characterized separately for structure and function, and the entire patch was assembled just before transplantation. Finally, the structure of the assembled multilayer cardiac patch was characterized before transplantation, and its ability to promote vascularization was assessed in vivo.

Fig. 1.

Steps in the bottom-up approach to assembling a functional cardiac patch.

Results and Discussion

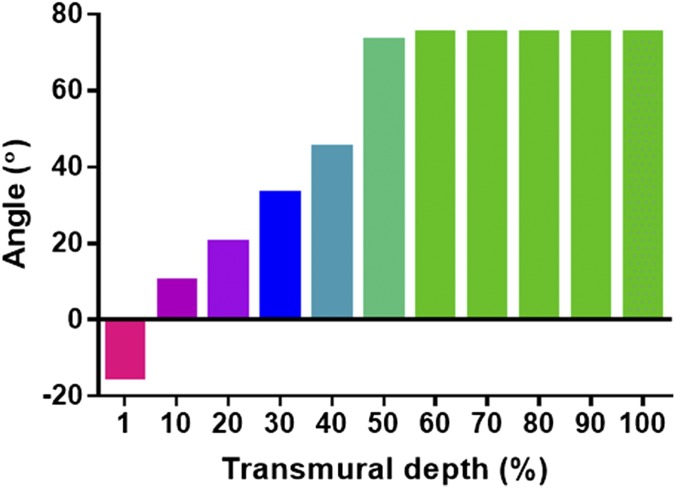

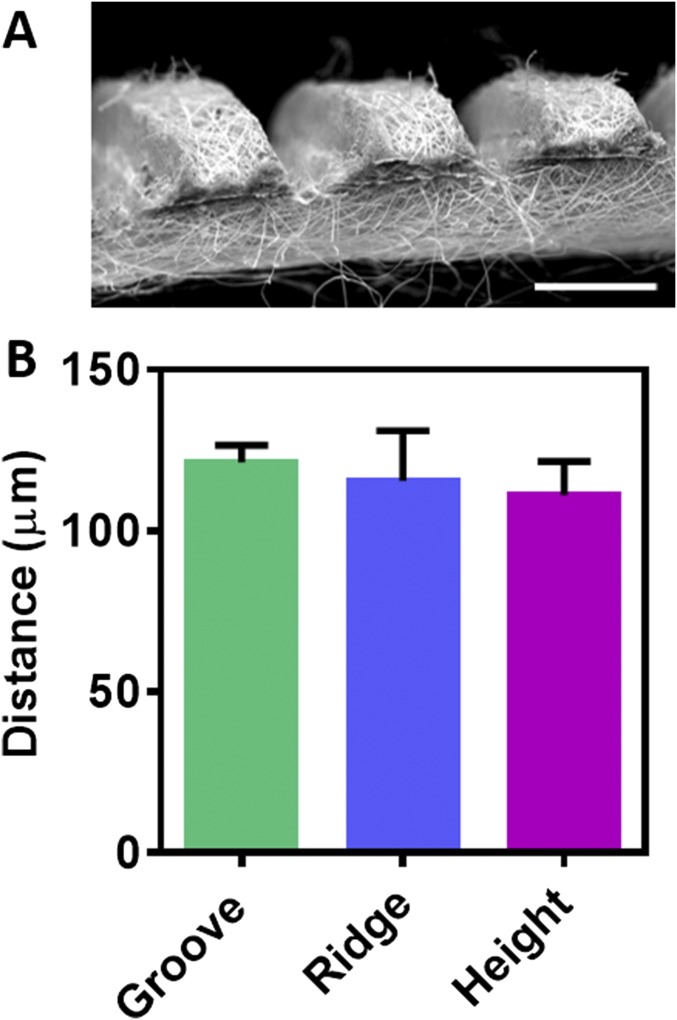

Tissues in the body are comprised of different cellular and extracellular layers. The myocardium is composed of anisotropic layers of cells and collagen fibers with varying orientations across its transmural depth (5, 6). To explore the variations in transmural orientation in detail, adult rat hearts were harvested, sliced, and stained for cells and collagens (Fig. 2A). Analysis of collagen fiber orientation revealed that the degree of alignment from the epicardial side to the endocardial side had a 100° shift (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S1). Currently, the only technique for assembling a shift in cell alignment is by assembling several tissue layers atop each other. To address this challenge, thin layers of fibrous scaffolds were fabricated by electrospinning of albumin (Fig. 2B). To increase the surface area of the fibrous scaffold and to mimic native anisotropy of the natural ECM, microgrooves were patterned onto the scaffold by a femtosecond laser (Fig. 2C, SI Materials and Methods, and Fig. S2A). To increase the mass transfer through the different layers, microholes (40 ± 0.8 µm in diameter) were created on the ridges of each layer (Fig. 2C). Such holes were previously shown to promote the efficient exchange of nutrients and oxygen (21). The pattern dimensions as measured using scanning laser confocal microscopy were a groove width of 115 ± 5 µm, ridge width of 120 ± 2 µm, and height of 110 ± 10 µm (Fig. 2D, SI Materials and Methods, and Fig. S2B). The patterned grooves increased the surface area of the scaffolds significantly, from 25 mm2 to 39 ± 0.9 mm2 (P = 0.0001) (Fig. 2E). Stacking several of these grooved scaffolds with a slight angle shift (Fig. 2F) may promote the essential circular contraction.

Fig. 2.

Biomimetic design and fabrication of patterned electrospun fiber scaffolds. (A) Schematics (Upper) and Masson’s trichrome staining of a transmural block cut from the ventricular wall (Lower) showing the macroscopic variation in fiber orientation across the wall. (B and C) SEM micrographs of planar electrospun scaffolds (B) and grooved electrospun scaffolds with microholes (C). (D) Confocal image of grooved electrospun scaffolds (Upper) and topography analysis (Lower). (E) Surface area. (F) Schematics (Left) and SEM micrographs (Right) of grooved electrospun scaffolds stacked with a slight angle shift. (G) Representative stress–strain curves. (H) Young’s modulus. The results represent mean values ± SEM (n ≥ 5 in each group). Statistical evaluations were performed by unpaired Student’s t tests. (Scale bars: 200 µm in B, C, and F; 20 µm in B and C Insets; 100 µm in D.)

Fig. S1.

Quantification of collagen fiber orientation throughout the LV wall.

Fig. S2.

Microgrooved scaffolds. (A) SEM micrograph of a cross-section of the scaffold. (Scale bar: 200 μm.) (B) Analysis of groove and ridge width (distance) and depth (height).

For proper integration with the healthy part of the heart, the mechanical properties of the patch should have similar characteristics. The Young's modulus of the human heart ranges between 200 and 500 kPa in the contracted state (25–27). Moreover, the left ventricle (LV) has unique mechanical anisotropy, with a measured anisotropy ratio of 2.1, that is essential for proper function (7). Fig. 2G shows the representative stress-strain behavior of the different scaffolds. Further analysis of these results revealed that, although the Young’s modulus of the planar layers was 950 ± 125 kPa, the microgrooved scaffolds had significantly lower Young’s modulus of 450 ± 20 kPa in the long axis of the grooves and 95 ± 25 kPa in the short axis (P = 0.0002 and P = 0.004, respectively) (Fig. 2H). The anisotropy ratio of the grooved scaffolds was 2.3, indicating their resemblance to the anisotropic LV and their potential use in cardiac patches that generate a strong contraction force. The mechanical properties and anisotropy can be controlled further by patterning different structures (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S3).

Fig. S3.

Micropatterned zigzag grooves. (A) SEM micrographs. (Scale bars: 250 μm, Left; 100 μm, Right). (B) Young’s modulus. (C) Mechanical anisotropy ratio.

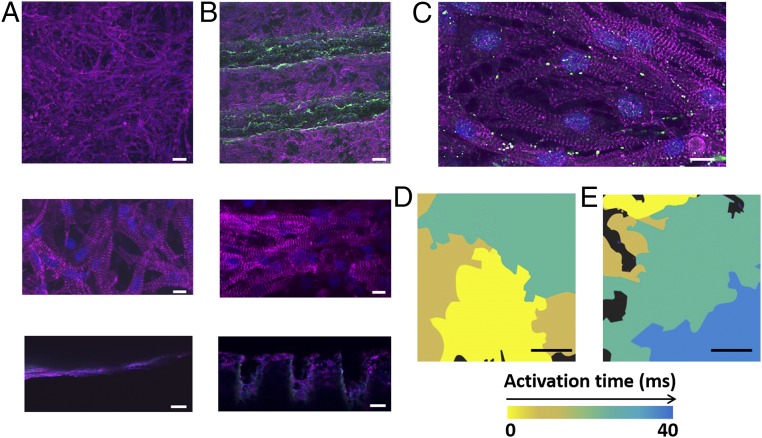

Next, we sought to evaluate the potential of the grooved fibrous layers to promote anisotropic cardiac tissue assembly. Cardiac cells were isolated from the ventricles of neonatal rats and were cultured for 7 d. Sarcomeric α-actinin immunostaining revealed that the cells cultured on the nonpatterned albumin fiber scaffolds assembled into a randomly oriented tissue (Fig. 3A). On the contrary, the cells in the grooved scaffolds acquired the micropattern and assembled into aligned cardiac cell bundles, as they would in their natural microenvironment (Fig. 3B). Higher-magnification images of the tissues revealed cell elongation and massive striation in both scaffolds. However, only the cells on the grooved scaffolds exhibited oriented striation (Fig. 3B). Side-view images revealed that, contrary to the planar scaffolds, cardiomyocytes in the patterned scaffolds were able to adhere to the walls of the grooves and thus formed thicker 3D structures (Fig. 3 A and B), with high expression of connexin 43 proteins, which are associated with electrical coupling between adjacent cells (Fig. 3C). Because tissue structure usually is translated to function, an analysis of the electrical signal propagation was performed by calcium imaging (Movies S1 and S2). As shown by the heat maps, while the electrical signal generated by the tissues cultured within the planar scaffolds propagated randomly (Fig. 3D), the cells in the patterned scaffolds transferred the signal in the direction of the grooves (Fig. 3E and Fig. S4). Analysis of electrical signal propagation at randomly chosen points revealed directional propagation only in the grooved scaffolds, not in the planar or the patterned scaffolds (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S5).

Fig. 3.

Cardiac tissue organization and function. (A and B) Immunofluorescence images of α-sarcomeric actinin (pink) in cardiomyocytes cultured within planar (A) and grooved (B) scaffolds. Cell nuclei are shown in blue. Bottom panels show side views of the tissue constructs. (C) Connexin 43 molecules (green) are found between adjacent cells, indicating on their electrical coupling. (D and E) Heat maps showing randomly oriented electrical signal propagation of an engineered cardiac tissue within the planar scaffolds (D) and anisotropic propagation within the grooved scaffolds (E). (Scale bars: 50 μm in A and B, Top and A and B, Bottom; 50 μm in A and B, Middle; 10 μm in C; 500 μm in D and E.)

Fig. S4.

Cardiac tissue organization on zigzag microgrooved scaffolds. (A) Immunofluorescent images of α-sarcomeric actinin (pink) of cardiomyocytes cultured in zigzag grooves. (B) Heat maps showing electrical signal propagation in a single zigzag groove. (Scale bars: 100 μm in A, Upper; 20 μm in A, Lower; 200 μm in B.)

Fig. S5.

Analysis of electrical signal propagation at randomly chosen points on the planar (A) and microgrooved (B) scaffolds.

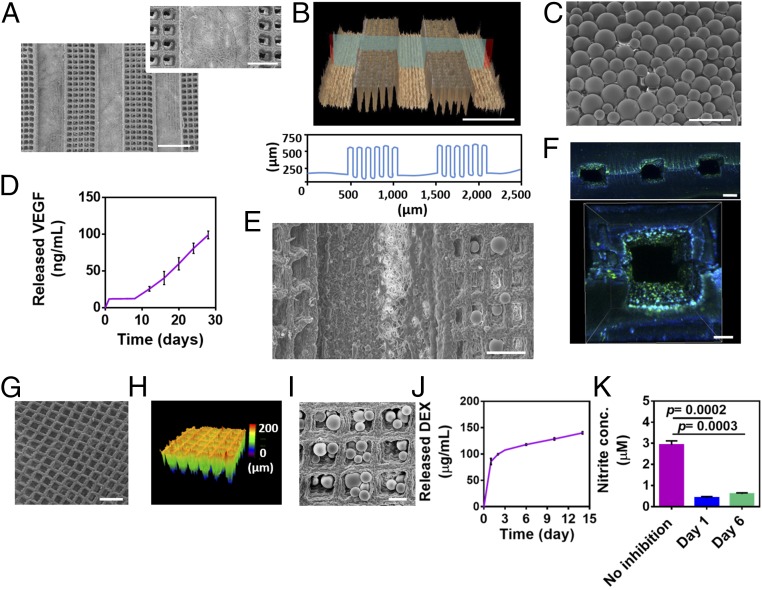

A major challenge that jeopardizes the clinical translation of engineered tissues is the inability to form and maintain thick, viable tissues (28, 29). 3D-engineered tissues require an efficient and constant supply of oxygen and nutrients for cell growth and function. In vitro, in the absence of a functional vascular network, perfusion bioreactors are used for mass transfer to the core of the tissue (30, 31). However, once the tissues are transplanted, the lack of proper vasculature jeopardizes the success of the treatment (32). One of the strategies for engineering prevascularized cardiac tissues is the coculture of cardiac cells with blood vessel-forming cells such as endothelial cells (33, 34). However, the two cell types require distinct conditions, including culture medium, growth factors, ECM topography and composition, and cultivation time. Here we designed a platform that allows separate growth, maturation, and organization of the endothelial cells that then are integrated with the cardiac compartment. Microtunnels with dimensions of 450 µm were patterned to form a predefined vasculature (Fig. 4 A and B). Cage-like structures were designed between the tunnels to accommodate controlled-release systems to continuously supply signals for vascularization. Next, double-emulsion PLGA microparticles (Fig. 4C) enabling a long-term release of VEGF (Fig. 4D) were deposited into the cages (Fig. 4E). Such a VEGF-release profile has been shown to improve the vascularization of an engineered tissue and to encourage anastomosis in vivo, contributing to better engraftment after transplantation (35, 36). The microtunnels then were seeded with endothelial cells to form large, closed lumens (Fig. 4F). VEGF release from the engineered blood vessels may encourage further sprouting of endothelial cells and the formation of new capillaries between the precultured vessels (36). Furthermore, the particles can be inserted into the cages more accurately by using a microinjector and even can be loaded with other growth factors or cytokines, such as PDGF or SDF-1, to attract other blood vessel-forming cells or IGF-1 for cardioprotection (37).

Fig. 4.

Fabrication of a predefined vascular layer and sustained release system layers. (A) SEM micrographs of micropatterned tunnels and the cage-like structures between them. (B) Confocal image of the microtunnels (Upper) and a topography analysis (Lower). (C) SEM micrograph of PLGA microparticles. (D) Cumulative release of VEGF. (E) SEM micrographs of PLGA microparticles deposited within the cage-like structures adjacent to the microtunnels. (F) Immunofluorescent images of CD31 (green) in endothelial cells cultured within the microtunnels to form lumens. Cell nuclei are shown in blue. (G and H) SEM (G) and confocal (H) micrographs of micropatterned cage-like structures. (I) SEM micrograph of PLGA particles deposited on cage-like structures. (J) Cumulative release of DEX. (K) Anti-inflammatory activity of DEX released from PLGA microparticles as indicated by the inhibition of NO secretion (measured as nitrite, a stable metabolite of NO) from activated macrophages. The results represent mean values ± SEM (n ≥ 5 in each group). Statistical evaluations were performed by unpaired Student’s t tests. (Scale bars: 500 μm in A and B; 200 μm in A, Inset, F, Upper, and G; 100 μm in C, E, and F, Lower; 50 μm in I.)

Another challenge in tissue engineering is the host response to the transplanted tissue. An acute inflammatory response against the engineered patch could profoundly limit the success of its integration and thereby jeopardize the regeneration process (38). Therefore, we next sought to incorporate a second microparticulate layer to release an anti-inflammatory drug from the patch’s outskirts to its surroundings. Cage-like structures were patterned (Fig. 4 G and H), and PLGA microparticles containing dexamethasone (DEX) were scattered on top (Fig. 4I). This anti-inflammatory layer was able to release the drug for at least 14 d (Fig. 4J) and attenuated the activation of macrophages, as measured by their nitric oxide (NO) secretion (Fig. 4K). Although this layer was designed to affect the patch’s surroundings by decreasing the immune response after transplantation, other small molecules can be loaded into the particles to affect the engineered tissue as well. For example, noradrenaline release near the cardiac layers may increase the contraction rate of the tissue. Recently our group has shown the ability to trigger the release of drugs by built-in layers of electronics (39). Integration of such a system as an additional layer within the engineered patch could provide on-demand spatiotemporal release of the different biofactors.

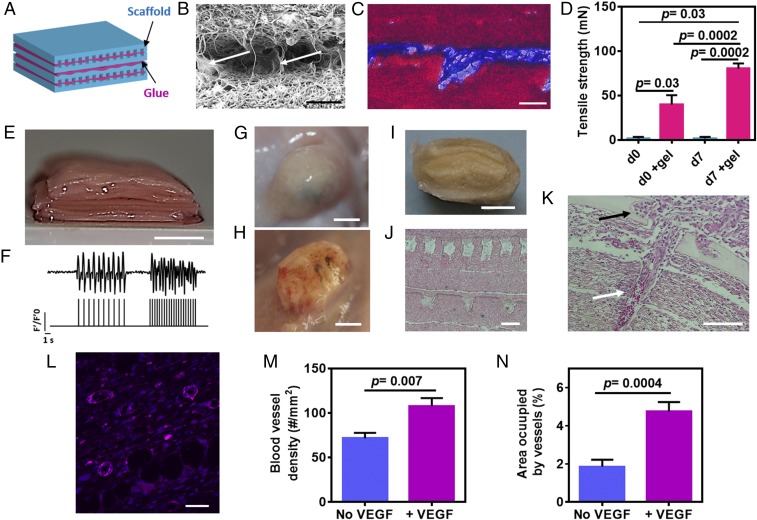

After engineering the distinct tissue layers, we next sought to integrate them to form a thick, modular tissue. Recently, our laboratory developed a thermoresponsive ECM-based hydrogel as a platform for cell delivery and tissue engineering (15). Here, we used the ability of the hydrogel to solidify at 37 °C to serve as a biological glue for layer integration. Thin layers of the glue were deposited between the tissue layers, and the assembled patch was heated to 37 °C in an incubator. Integration then was assessed by SEM, histology, and immunostaining (Fig. 5 B and C, SI Materials and Methods, and Fig. S6 B and C). Although the ECM hydrogel was able to glue the layers, the layers were not tightly packed, allowing the diffusion of nutrients and oxygen. Next, the binding force between the different layers was assessed (Fig. 5D). As shown by the measurements of tensile strength immediately after integration, the force needed to separate the glued layers was significantly greater than the force needed to separate nonglued layers (P = 0.03). More importantly, the binding force between the ECM-glued layers was strong enough to withstand manual manipulation and surgical suturing to the host. Culturing the integrated layers further for 7 d significantly strengthened their adherence (P = 0.0002), possibly via the additional secretion of ECM proteins by the cells.

Fig. 5.

In vitro assembly and in vivo vascularization of a 3D multifunctional patch. (A) Schematic of assembled scaffolds (blue) integrated by thin layers of glue (pink). (B and C) Micrographs of two layers integrated by ECM glue and visualized by SEM (B) and Masson’s trichrome staining (C) (collagen is stained in blue, scaffolds are stained in red). Arrowheads in B indicate the presence of the glue. (D) Adhesion strength. (E) Assembled layers forming a 5-mm-thick tissue. (F) Quantification of calcium transients (via normalized fluorescence intensity) without stimulation or with 1- or 2-Hz stimulation. The, stimulation pattern can be seen in the lower part of the figure. (G and H) Vascularization of the patch without (G) and with (H) VEGF-releasing particles 2 wk after s.c. transplantation in rats. (I) A cross-section of the explanted patch. (J) H&E staining of thin sections of the explanted patch. (K) Infiltration of a host blood vessel containing red blood cells (white arrow) into the engineered construct (black arrow). (L) Mature blood vessels populated the tissue construct with the sustained VEGF release as judged by the stained smooth muscle cells [pink, smooth muscle actin (SMA); blue, cell nuclei]. (M and N) Blood vessel density (M) and the percentage of the area occupied by the blood vessels (N). The results represent mean values ± SEM (n ≥ 3 in each group). Statistical evaluations were performed by unpaired Student’s t tests. (Scale bars: 50 μm in B, C, and L; 100 μm in J and K; 5 mm in E and G–I.)

Fig. S6.

Layer assembly and integration. (A) Images showing the adhesion of several tissue layers, revealing that the layers at 90° to the ground did not separate from one another. (B and C) Immunofluorescent images of a single tissue layer (B) and three integrated layers (C) stained for α-sarcomeric actinin in cardiomyocytes (pink) and collagen (green) comprising the ECM glue. Cell nuclei are stained in blue. (D and E) SEM micrographs of two layers of vasculature glued on top of each other to form closed lumens and incorporated between two cardiac tissue layers (D) and a cross-section of the DEX layer (E). (F) H&E staining of a cross-section of the DEX layer 2 wk after transplantation, showing the presence of a PLGA microparticle (in yellow). (Scale bars: 5 mm in A; 20 μm in B; 100 μm in C; 200 μm in D; 20 μm in E; 50 μm in F.)

Because cardiac tissues and blood vessels may need different assembly conditions (including cultivation periods, growth factors, and supporting matrices), 7-d cardiac layers and 3-d endothelial cell layers were integrated together with the controlled-release layers to form a 5-mm–thick cardiac patch. The engineered tissue was composed of six cardiac layers, six endothelial cell layers with VEGF particles, and two layers of DEX-releasing microparticles (Fig. 5E). To create the closed lumens, two layers of vasculature were simply glued on top of each other and were incorporated between two cardiac tissue layers (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S6D). The DEX layers were integrated to both ends of the construct to affect the patch’s surroundings (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S6E).

Because the native myocardium has tight connections in all directions, we next sought to evaluate the electrical coupling in the z-direction between the different cardiac layers. Before cardiac cell seeding, thin metal electrodes were deposited on an electrospun fiber scaffold, enabling local electrical stimulation of the cells within. Next, five layers of cardiac tissues were stacked on this electrode-containing layer to create the thick patch with an upper cardiac layer that was pretreated with calcium dye. Then electrical stimuli (1 or 2 Hz) were applied to the bottom layer, and the corresponding calcium wave fronts were recorded from the upper layer, indicating electrical integration within the z-direction (Fig. 5F and Movie S3).

Finally, we assessed the ability of our modular cardiac patch to promote vascularization in vivo. Cellular patches with or without VEGF-releasing microparticles were s.c. transplanted in rats for 2 wk before the rats were killed. A macroscopic view of the patches in the animals suggested that, while the patches without the VEGF remained white, the VEGF-loaded patches were filled with blood vessels as indicated by their red color (Fig. 5 G and H). Cross-sectioning the patches revealed that the structure of the layers was maintained (Fig. 5 I and J). Furthermore, VEGF microparticles could be seen on the blood-vessel layer, suggesting that although the particles had started to degrade and release their content, some of them were still intact within their mesh (SI Materials and Methods and Fig. S6F). Histological analysis and immunostaining the extracts for smooth muscle cells, which stabilize blood vessels, revealed that the release of VEGF encouraged the infiltration of blood vessels into the patch and its surroundings (Fig. 5 K and L, SI Materials and Methods, and Fig. S7). Moreover, red blood cells within the host blood vessels were seen entering the core of the patch and into its channels, indicating anastomosis between the host vasculature and the engineered tissue (Fig. 5K). Quantification of blood vessels within the engineered patch revealed a significantly higher number of vessels per square millimeter of tissue (P = 0.007) (Fig. 5M) in the patch containing VEGF-releasing particles than in the pristine scaffolds. Moreover, the percentage of the total area of blood vessels within the VEGF-releasing patch was significantly higher (P = 0.0004) (Fig. 5N). Taken together, these results indicate the ability of the VEGF microparticulate layer to improve blood vessel infiltration into the cardiac patch.

Fig. S7.

Mature blood vessels populated the tissue construct with the sustained VEGF-release system as judged by anti-SMA immunofluorescence (pink). Cell nuclei are shown in blue. (Scale bars: 100 μm in A; 50 μm in B.)

To conclude, here we present a platform for assembling a modular, thick, cardiac patch, containing layers of cardiac tissues, blood vessels, and proangiogenic and anti-inflammatory factors. The 3D structural complexity of the fibrous ECM was recapitulated by the assembly of micropatterned electrospun layers, mimicking the variation in collagen alignment throughout the LV wall. We have shown that these layers mimic both the stiffness and mechanical anisotropy of the heart muscle and therefore may improve the potential of the cardiac patch to integrate properly to the heart muscle. Cardiac cells cultured within these layers assembled into aligned and elongated cardiac bundles resembling the natural tissue morphology. In addition, we have engineered predefined vasculature with sufficient distance from the cardiac tissue to enable the diffusion of oxygen and nutrients. This platform enabled a simple, scalable production of millimeter-thick tissues simply by placing one on top of another and integrating them by an ECM-based biological glue. Unlike other tissue-engineering approaches, such as 3D printing or using macroporous scaffolds, this method enabled the engineering of individual layers with each layer cultured under its optimal conditions before assembly. Microparticulate systems for prolonged release of growth factors or small molecules could be incorporated into the patch easily and affected the engineered tissue or the host according to the physiological needs. Although our data support the engineering of a vascularized cardiac patch, in the future different structures can be patterned on electrospun fibers to provide support to other tissues that are comprised of defined layers, including the liver and lung.

SI Materials and Methods

Masson's Trichrome Staining.

Adult rat hearts were cryo-fixed and sectioned into 10-μm slices. The sections were stained with Masson’s trichrome (Bio-Optica) for cell and collagen detection.

Electrospinning Albumin Fiber Scaffolds.

BSA [Fraction V, 10% and 14% (wt/vol)] (MP Biomedicals) was dissolved in tetrafluoroethylene (TFE) and distilled water (9:1), following by the addition of excess β-mercaptoethanol (Merck) for overnight reaction. The solution was electrospun at room temperature using a syringe pump (Harvard Apparatus) delivered at a rate of 2 mL/h. A high-voltage supply (Glassman High Voltage) was used to apply a 12-kV potential between the capillary tip and the grounded aluminum collector placed at a distance of 14 cm from the capillary tip.

Micropatterning.

A Master-Femto femtosecond laser micromachining system (ELAS, Ltd.) was used for the micropatterning of albumin fiber scaffolds (1,026 nm, 1–5 W, 150 Hz).

Scaffold 3D Imaging and Topographical Analysis.

Confocal images of the micropatterned scaffolds were taken using an Olympus LEXT 4000 confocal microscope.

SEM.

Samples were mounted onto aluminum stubs with conductive paint and were sputter-coated with an ultrathin (150-Å) layer of gold in a Polaron E5100 coating apparatus (Quorum Technologies). The samples were viewed under a JCM-6000PLUS NeoScope Benchtop scanning electron microscope (JEOL USA, Inc.).

Mechanical Properties.

Albumin fiber scaffolds.

Scaffolds were cut into a rectangular shape (gauge length: 20 mm; width: 4 mm) and were tested using a model LS1 tensile testing instrument (Lloyd Instruments, Ltd.) with a 20-N load cell at a rate of 5 mm/min.

ECM glue integration.

Scaffolds were cut into a rectangular shape (gauge length: 20 mm; width: 4 mm). Then a 10-µL drop of ECM glue was placed on the short edge of one rectangular scaffold, and a second scaffold was placed on top of the drop, forming a congruent area of 4 × 4 mm between the two scaffolds. Later, the scaffolds were incubated for 30 min and then were tested using a Lloyd tensile testing instrument (model LS1) with a 5-N load cell at a rate of 3 mm/min.

Cardiac Cell Isolation, Seeding, and Cultivation.

Cardiac cells were isolated according to Tel Aviv University ethical use protocols. Briefly, the left ventricles of 0- to 3-d-old neonatal Sprague–Dawley rats (Envigo Laboratories) were harvested, and cells were isolated using six cycles (30 min each at 37 °C) of enzyme digestion with collagenase type II (95 U/mL) (Worthington) and pancreatin (0.6 mg/mL) (Sigma-Aldrich) in DMEM (1.8 mM CaCl2·2H2O,5.36 mM KCl, 0.81 mM MgSO4·7H2O, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.44 mM NaHCO3, and 0.9 mM NaH2PO4). After each round of digestion cells were centrifuged at 600 × g for 5 min and were resuspended in culture medium composed of M-199 supplemented with 0.6 mM CuSO45·H2O, 0.5 mM ZnSO4·7H2O, 1.5 mM vitamin B12, 500 U/mL penicillin, 100 mg/mL streptomycin, and 0.5% (vol/vol) FBS. To enrich the cardiomyocyte population, cells were suspended in culture medium with 5% (vol/vol) FBS and were preplated twice for 45 min. Cell number and viability were determined by a hemocytometer and trypan blue exclusion assay. Two million cardiac cells were seeded onto the devices by adding 15 μL of the suspended cells followed by a 45-min incubation period in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Then cell constructs were supplemented with culture medium [5% (vol/vol) FBS] and were incubated further.

Immunostaining.

Cell constructs were fixed and permeabilized in 100% cold methanol for 10 min, washed three times in DMEM-based buffer, and then blocked for 1 h at room temperature in DMEM-based buffer containing 2% (vol/vol) FBS. Then the samples were washed three times. Cardiac tissues were incubated with primary mouse anti–α-sarcomeric actinin antibody (1:750) (Sigma-Aldrich), washed three times, and incubated for 1 h with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (1:500) (Jackson). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were stained for CD31 (1:100) (Abcam), washed three times, and incubated for 1 h with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:500) (Jackson). For nuclei detection, the cells were incubated for 3 min with Hoechst 33258 (1:100) (Sigma) and were washed three times. Samples were visualized using a scanning laser confocal microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ni).

Calcium Imaging.

Constructs were incubated with 10 μM fluo-4 AM (Invitrogen) and 0.1% Pluronic F-127 (Sigma-Aldrich) for 45 min at 37 °C. Constructs then were washed in medium and imaged using an inverted fluorescent microscope (Nikon Eclipse TI). Videos were acquired with an ORCA-Flash 4.0 digital complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) camera (Hamamatsu) at 100 frames/s using NIS-Elements software (Nikon). Electrical signal propagation was measured by ImageJ (NIH).

PLGA Particles Loaded with VEGF.

PLGA particles loaded with VEGF were prepared using the solid-in-oil-in-oil emulsion solvent evaporation technique. Briefly, 150 mg of PLGA (75% average molecular weight 7,000–17,000, acid terminated, and 25% average molecular weight 30,000–60,000) (Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in 750 µL of acetonitrile. Next, 7.5 µg of VEGF (PeproTech) were dissolved in 112 µL of double-distilled deionized water, 15 µL of 20% (wt/vol) aqueous BSA solution, and 22.5 µL of 7% (wt/vol) aqueous sucrose solution and were stirred. Next, 600 µL of acetonitrile solution was added in 150-µL increments and was stirred for 2 min. This solution then was added to a 15-mL solution of acetonitrile, stirred for 2 min, and centrifuged for 10 min at 2250 × g. The precipitate was washed twice with acetonitrile. The remaining acetonitrile was removed, and the precipitate was suspended in the PLGA solution, stirred for 5 min, and sonicated for 1 min. This solution was added to 75 mL of light mineral oil with 2% (vol/vol) Span-80 (Sigma-Aldrich) and was stirred at 40 × g under reduced pressure overnight. The next day, the microparticles were washed three times with isopropanol, dried under reduced pressure, and suspended in 2% (vol/vol) BSA solution in PBS. To measure VEGF release from the particles, the particles were suspended in microcentrifuge tubes containing PBS solution with 0.1% BSA and were incubated at 37 °C under continuous rotation at 15 rpm. VEGF concentration was determined using a human VEGF ELISA kit (PeproTech).

PLGA Particles Loaded with DEX.

An oil-in-water emulsion solvent extraction/evaporation technique was used. One hundred milligrams of PLGA (average molecular weight 30,000–60,000) (Sigma-Aldrich) were dissolved in 400 µL of methylene chloride; then 10 mg of DEX was dispersed in this solution, and the solution was stirred for 1 h. This organic phase was added to 2 mL of a 1% (wt/vol) aqueous polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) solution (molecular weight 25,000), and the solution was stirred for 3 min at 70 × g. Next, the emulsion was added to 30 mL of a 0.1% (wt/vol) aqueous PVA solution, which was stirred under reduced pressure for 3 h at 25 °C. The resulting microspheres were washed three times with double-distilled deionized sterile water. To measure DEX release, the particles were suspended in a PBS solution with 0.1% BSA, and microcentrifuge tubes were rotated at 15 rpm at 37 °C. The amount of released DEX was quantified by absorbance at 242 nm (a characteristic band of DEX) using an ND-1000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies).

The Effect of Released DEX on NO Production in Macrophages.

RAW 264.7 cells (ATCC) were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified, 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere in DMEM (without phenol red) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM l-glutamine (Biological Industries). RAW 264.7 cells (3.25 × 104, in a total volume of 60 μL) were seeded in the wells of a 96-well plate. Twenty-four hours later, the cells were supplemented with an additional 20 μL of medium without or with the released DEX that were sampled at day 1 and day 6. Twenty-four hours later, 20 μL of growth medium containing 25 ng/mL of IFN-γ (PeproTech) was added to each well, reaching a final concentration of 5 ng/mL After 24 h incubation, 50-μL samples of cell growth medium were analyzed for nitrite concentration (used as an indicator of NO production) using Griess reagent (Promega). Cell viability was determined by thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (n ≥ 5 in each group).

Assessment of Electrical Signal Transfer Between the Stacked Layers.

Two gold electrodes (300 nm) were evaporated onto the bottom albumin layer with a 1-cm distance between them. Cells were seeded between the electrodes to form the bottom layer of the tissue. Pristine cardiac layers were glued onto the bottom layer to allow the cells to migrate and create cell–cell interactions in the z axis. After 7 d of incubation, calcium imaging of the top layer was performed. Then the constructs were washed in medium, and the top layer was imaged using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TI). Movies were acquired with an ORCA-Flash 4.0 camera (Hamamatsu) at 100 frames/s.

In Vivo Implantation and Histology.

Recipient SD male rats (150–200 g) (Envigo Laboratories) were anesthetized using a combination of ketamine (40 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) according to Tel Aviv University ethical use protocols. Samples were implanted s.c. by creating a small incision on the rat’s back. Scaffolds were inserted into the cavity created by the incision. Rats were killed 2 wk after transplantation, and the samples were extracted, dehydrated in graduated ethanol steps (70–100%), fixed in formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 μm thick) were prepared using a microtome and were stained with H&E. Samples were visualized using an inverted fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse TI). For immunofluorescence, sections were rehydrated (100–0%), and then antigen retrieval was performed in citrate buffer. Sections then were stained with primary rabbit anti-SMA (1:100; Abcam) and Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (1:500; Jackson) and were visualized using a scanning laser confocal microscope (Nikon Eclipse Ni).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis data are presented as means ± SEM. Differences between samples were assessed by a Student’s t test. All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software). P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Materials and Methods

Detailed descriptions of scaffold fabrication, mechanical testing, cardiac cell isolation and seeding, immunostaining, calcium imaging, electrical signal transfer analysis, PLGA microparticle fabrication, macrophage activation test, ELISA analysis, in vivo implantation, histology, and imaging, are provided in SI Materials and Methods. All animal experiments were performed according to Tel Aviv University ethical use protocols.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

S.F. is supported by the Adams Fellowship Program of the Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities. R.F. is the recipient of a Marian Gertner Institute for Medical Nanosystems Fellowship. T.D. received support from European Research Council Starting Grant 637943, the Slezak Foundation, and the Israeli Science Foundation (700/13). This work is part of S.F.’s doctoral thesis at Tel Aviv University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1615728114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Fleischer S, Dvir T. Tissue engineering on the nanoscale: Lessons from the heart. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24(4):664–671. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dvir T, Timko BP, Kohane DS, Langer R. Nanotechnological strategies for engineering complex tissues. Nat Nanotechnol. 2011;6(1):13–22. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogle BM, et al. Distilling complexity to advance cardiac tissue engineering. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8(342):342ps313–342ps313. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad2304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pope AJ, Sands GB, Smaill BH, LeGrice IJ. Three-dimensional transmural organization of perimysial collagen in the heart. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295(3):H1243–H1252. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00484.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.LeGrice IJ, et al. Laminar structure of the heart: Ventricular myocyte arrangement and connective tissue architecture in the dog. Am J Physiol. 1995;269(2 Pt 2):H571–H582. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.269.2.H571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corno AF, Kocica MJ, Torrent-Guasp F. The helical ventricular myocardial band of Torrent-Guasp: Potential implications in congenital heart defects. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29(Suppl 1):S61–S68. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engelmayr GC, Jr, et al. Accordion-like honeycombs for tissue engineering of cardiac anisotropy. Nat Mater. 2008;7(12):1003–1010. doi: 10.1038/nmat2316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim D-H, et al. Nanoscale cues regulate the structure and function of macroscopic cardiac tissue constructs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(2):565–570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906504107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleischer S, et al. Spring-like fibers for cardiac tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 2013;34(34):8599–8606. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleischer S, Shevach M, Feiner R, Dvir T. Coiled fiber scaffolds embedded with gold nanoparticles improve the performance of engineered cardiac tissues. Nanoscale. 2014;6(16):9410–9414. doi: 10.1039/c4nr00300d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feinberg AW, et al. Controlling the contractile strength of engineered cardiac muscle by hierarchal tissue architecture. Biomaterials. 2012;33(23):5732–5741. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feinberg AW, et al. Muscular thin films for building actuators and powering devices. Science. 2007;317(5843):1366–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.1146885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruvinov E, Cohen S. Alginate biomaterial for the treatment of myocardial infarction: Progress, translational strategies, and clinical outlook: From ocean algae to patient bedside. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;96:54–76. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shevach M, Soffer-Tsur N, Fleischer S, Shapira A, Dvir T. Fabrication of omentum-based matrix for engineering vascularized cardiac tissues. Biofabrication. 2014;6(2):024101. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/6/2/024101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shevach M, et al. Omentum ECM-based hydrogel as a platform for cardiac cell delivery. Biomed Mater. 2015;10(3):034106. doi: 10.1088/1748-6041/10/3/034106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shevach M, Fleischer S, Shapira A, Dvir T. Gold nanoparticle-decellularized matrix hybrids for cardiac tissue engineering. Nano Lett. 2014;14(10):5792–5796. doi: 10.1021/nl502673m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vunjak-Novakovic G, et al. Challenges in cardiac tissue engineering. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16(2):169–187. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang YS, et al. Bioprinting 3D microfibrous scaffolds for engineering endothelialized myocardium and Heart-on-a-Chip. Biomaterials. 2016;110:45–59. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolewe ME, et al. 3D structural patterns in scalable, elastomeric scaffolds guide engineered tissue architecture. Adv Mater. 2013;25(32):4459–4465. doi: 10.1002/adma.201301016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ye X, et al. Scalable units for building cardiac tissue. Adv Mater. 2014;26(42):7202–7208. doi: 10.1002/adma.201403074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang B, et al. Biodegradable scaffold with built-in vasculature for organ-on-a-chip engineering and direct surgical anastomosis. Nat Mater. 2016;15(6):669–678. doi: 10.1038/nmat4570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin M, Ishii O, Sueda T, Vacanti JP. Contractile cardiac grafts using a novel nanofibrous mesh. Biomaterials. 2004;25(17):3717–3723. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleischer S, Miller J, Hurowitz H, Shapira A, Dvir T. Effect of fiber diameter on the assembly of functional 3D cardiac patches. Nanotechnology. 2015;26(29):291002. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/26/29/291002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleischer S, et al. Albumin fiber scaffolds for engineering functional cardiac tissues. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111(6):1246–1257. doi: 10.1002/bit.25185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weis SM, et al. Myocardial mechanics and collagen structure in the osteogenesis imperfecta murine (oim) Circ Res. 2000;87(8):663–669. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.8.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Omens JH. Stress and strain as regulators of myocardial growth. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1998;69(2-3):559–572. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(98)00025-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coirault C, et al. Increased compliance in diaphragm muscle of the cardiomyopathic Syrian hamster. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1998;85(5):1762–1769. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.5.1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parsa H, Ronaldson K, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Bioengineering methods for myocardial regeneration. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;96:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sapir Y, Cohen S, Friedman G, Polyak B. The promotion of in vitro vessel-like organization of endothelial cells in magnetically responsive alginate scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2012;33(16):4100–4109. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dvir T, Benishti N, Shachar M, Cohen S. A novel perfusion bioreactor providing a homogenous milieu for tissue regeneration. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(10):2843–2852. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Radisic M, Marsano A, Maidhof R, Wang Y, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Cardiac tissue engineering using perfusion bioreactor systems. Nat Protoc. 2008;3(4):719–738. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montgomery M, Zhang B, Radisic M. Cardiac tissue vascularization: From angiogenesis to microfluidic blood vessels. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2014;19(4):382–393. doi: 10.1177/1074248414528576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caspi O, et al. Tissue engineering of vascularized cardiac muscle from human embryonic stem cells. Circ Res. 2007;100(2):263–272. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000257776.05673.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lesman A, et al. Transplantation of a tissue-engineered human vascularized cardiac muscle. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16(1):115–125. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2009.0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marsano A, et al. The effect of controlled expression of VEGF by transduced myoblasts in a cardiac patch on vascularization in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 2013;34(2):393–401. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freeman I, Cohen S. The influence of the sequential delivery of angiogenic factors from affinity-binding alginate scaffolds on vascularization. Biomaterials. 2009;30(11):2122–2131. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.12.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dvir T, et al. Prevascularization of cardiac patch on the omentum improves its therapeutic outcome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(35):14990–14995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812242106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vishwakarma A, et al. Engineering Immunomodulatory Biomaterials To Tune the Inflammatory Response. Trends Biotechnol. 2016;34(6):470–482. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feiner R, et al. Engineered hybrid cardiac patches with multifunctional electronics for online monitoring and regulation of tissue function. Nat Mater. 2016;15(6):679–685. doi: 10.1038/nmat4590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.