Significance

Women suffering from malnutrition and athletes with low body fat become infertile as a result of low gonadotropin secretion. Gonadotropin release is determined by a neural endocrine circuit; however, the metabolic cues that are responsible for attenuating this axis during starvation remain unclear. Here, we find that starvation-activated agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons can inhibit the reproductive neuroendocrine circuit. Furthermore, artificial activation of genetically defined AgRP neurons is sufficient to delay estrous cycle length and parturition in female mice. This work demonstrates a mechanism by which AgRP neurons can relay metabolic information to the fertility axis during starvation.

Keywords: agouti-related peptide, fertility, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone, kisspeptin, leptin

Abstract

Mammalian reproductive function depends upon a neuroendocrine circuit that evokes the pulsatile release of gonadotropin hormones (luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone) from the pituitary. This reproductive circuit is sensitive to metabolic perturbations. When challenged with starvation, insufficient energy reserves attenuate gonadotropin release, leading to infertility. The reproductive neuroendocrine circuit is well established, composed of two populations of kisspeptin-expressing neurons (located in the anteroventral periventricular hypothalamus, Kiss1AVPV, and arcuate hypothalamus, Kiss1ARH), which drive the pulsatile activity of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons. The reproductive axis is primarily regulated by gonadal steroid and circadian cues, but the starvation-sensitive input that inhibits this circuit during negative energy balance remains controversial. Agouti-related peptide (AgRP)-expressing neurons are activated during starvation and have been implicated in leptin-associated infertility. To test whether these neurons relay information to the reproductive circuit, we used AgRP-neuron ablation and optogenetics to explore connectivity in acute slice preparations. Stimulation of AgRP fibers revealed direct, inhibitory synaptic connections with Kiss1ARH and Kiss1AVPV neurons. In agreement with this finding, Kiss1ARH neurons received less presynaptic inhibition in the absence of AgRP neurons (neonatal toxin-induced ablation). To determine whether enhancing the activity of AgRP neurons is sufficient to attenuate fertility in vivo, we artificially activated them over a sustained period and monitored fertility. Chemogenetic activation with clozapine N-oxide resulted in delayed estrous cycles and decreased fertility. These findings are consistent with the idea that, during metabolic deficiency, AgRP signaling contributes to infertility by inhibiting Kiss1 neurons.

Starvation-associated infertility is characterized by insufficient circulating gonadotropin hormones, yet the starvation-sensitive input responsible for this physiological adaptation remains unknown (1–3). Gonadal hormone-sensitive neurons [located in the anteroventral periventricular hypothalamus (AVPV), Kiss1AVPV, and arcuate hypothalamus (ARH), Kiss1ARH] drive the pulsatile activity of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) neurons and subsequent neuroendocrine release of gonadotropins from the pituitary (4–6). Within this circuit, Kiss1ARH neurons are of particular interest during starvation because they respond to negative feedback from gonadal steroids. In females, low or depleted estrogen levels evoke transcriptional activation of Kiss1ARH neurons (7–9), and stimulation of genetically defined Kiss1ARH neurons in vivo is sufficient to evoke gonadotropin release (10). During starvation, gonadal steroid levels plummet, yet Kiss1ARH neurons are unable to drive gonadotropin release. We hypothesize that some other input that is sensitive to metabolic status (energy reserves) inhibits the neuronal circuitry regulating gonadotropin release during starvation.

Agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons express the inhibitory neuropeptides AgRP and neuropeptide Y (NPY), and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (11–13), they are activated during starvation, and they project their axons to areas of the brain containing both Kiss1 and GnRH neurons (14). Ablation of AgRP neurons restores fertility in mice lacking leptin (15). Thus, we hypothesized that during starvation, AgRP neurons may inhibit the neuroendocrine reproductive circuit as a means of blocking fertility when energy reserves are insufficient to meet the demands of pregnancy and lactation. We use a combination of electrophysiology and molecular genetic technologies to explore this hypothesis.

Results

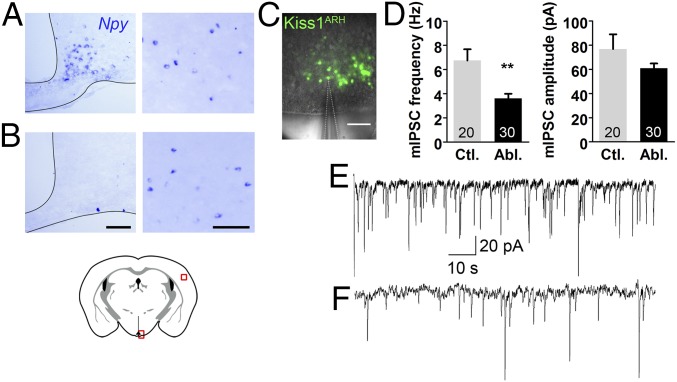

Kiss1ARH Neurons Receive Less Inhibitory Input in the Absence of AgRP Neurons.

If AgRP neurons normally inhibit Kiss1 neurons, then we predicted that Kiss1 neurons would be more active in mice lacking AgRP neurons. Ablation of AgRP neurons in neonatal mice was achieved by administering diphtheria toxin to neonatal AgrpDTR mice that express the human diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) from the Agrp gene locus (16). These mice grow up to be relatively normal, unlike the starvation phenotype that ensues after diphtheria toxin (DT) treatment in adult AgrpDTR mice (16, 17), and they maintain normal appetite, fertility, and maternal behavior (18). We made a genetic cross between AgrpDTR and Kiss1Cre:GFP mice, treated the mice as neonates with diphtheria toxin and then measured presynaptic inhibition of the resulting adult double transgenic mice. To document the efficacy of the toxin treatment, we performed in situ hybridization for Npy, a gene that is coexpressed with Agrp in the arcuate region of the hypothalamus. Npy transcripts were gone from the ARH of toxin-treated mice relative to controls, but cortical Npy-expressing neurons were unaffected (Fig. 1 A and B). We performed whole-cell, patch-clamp recordings of fluorescently labeled Kiss1Cre:GFP neurons in slices (Fig. 1C) from the ARH. In the absence of AgRP neurons, the frequency of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) were significantly reduced in Kiss1ARH neurons relative to intact controls and there was no significant change in current amplitude (Fig. 1 D–F); these results are hallmarks of diminished inhibitory, presynaptic input.

Fig. 1.

Kiss1ARH neurons receive less presynaptic inhibition in the absence of AgRP neurons. (A and B) In situ hybridization of Npy in the arcuate hypothalamus (Left) and cortex (Right). (B) Npy expression was abolished in the arcuate of AgrpDTR mice following neonatal diphtheria toxin exposure. (C) To visualize Kiss1ARH neurons, both experimental and control animals were crossed to a Kiss1Cre:GFP line and ovariectomized before slice recordings. A fluorescent Kiss1Cre:GFP-patched neuron in the arcuate is demonstrated. (D) The average synaptic currents (mIPSCs) of Kiss1ARH neurons occurred less frequently (Left) but with a similar amplitude (Right) in the absence of AgRP neurons (n = 20, 30; recorded cells). Frequency is as follows: control vs. ablated. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test: control (five animals, 20 cells total recorded; M = 6.74, SE = 0.94) vs. ablated (four animals, 30 cells total recorded; M = 3.61, SE = 0.38): t(48) = 3.50, **P = 0.001. Amplitute is as follows: control vs. ablated. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test: control (five animals, 20 cells total recorded; M = 76.83, SE = 12.22) vs. ablated (four animals, 30 cells total recorded; M = 60.93, SE = 3.90): t48) = 1.44, P = 0.1. (E and F) Representative traces of Kiss1ARH neurons in the presence and absence of AgRP neurons, respectively. (Scale bars, 100 μm.)

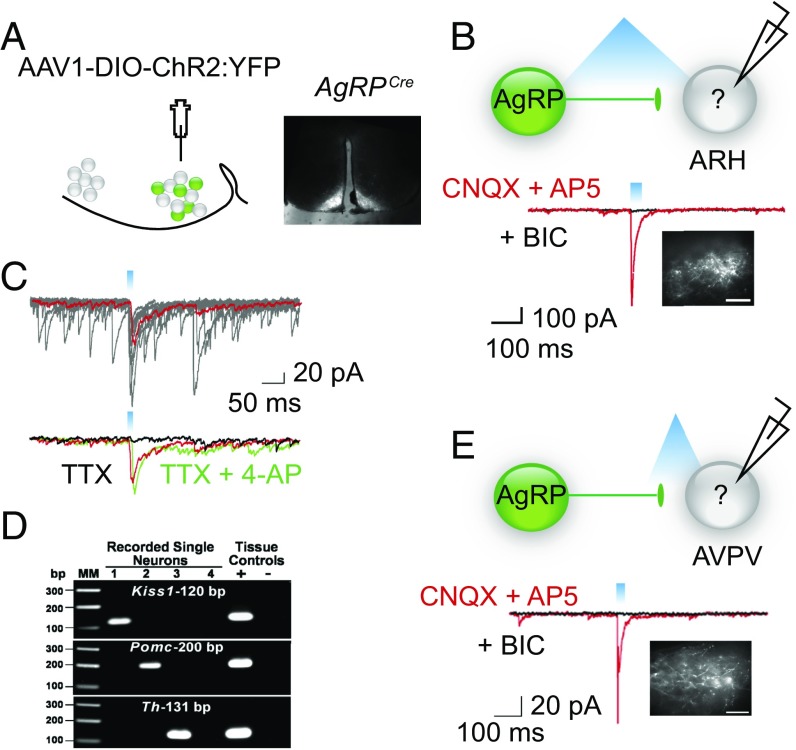

AgRP Signaling Directly Inhibits Both Kiss1ARH and Kiss1AVPV Neurons.

To address whether AgRP neurons directly synapse on Kiss1 cells, we evaluated the circuit using optogenetics (19). AgrpCre:GFP-expressing neurons were transduced with an adeno-associated virus containing a conditional channelrhodopsin (AAV1-EF1α-DIO-ChR2:YFP) (Fig. 2A). As proof of principle, we demonstrated that blue light was sufficient to depolarize ChR2-expressing AgRP neurons (Fig. S1). We next stimulated ChR2 in AgRP axons with blue light (1–20 Hz, 10- to 25-ms pulse width), evaluated light-evoked IPSCs in nonfluorescent cells in the ARH in the presence of glutamate receptor blockers [6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) and (2R)-amino-5-phosphovoleric acid (AP5)], and then harvested contents from the recorded cells and performed reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) for Kiss1, Pomc, and Th to identify specific neurons (Fig. 2 B–D). Post hoc analysis revealed that 5 of 15 neurons in the ARH expressed Kiss1 and they all displayed light-evoked IPSCs that were blocked in the presence of bicuculline (BIC), a GABAA receptor antagonist. The evoked current was time locked (Fig. 2B) to the light flash (latency, range 3–4 ms; jitter 0.40 ± 0.08 ms, n = 5) (20). Furthermore, bath application of the potassium channel blocker, 4-aminopyridine (4-AP), rescued light-evoked current in the presence of tetrodotoxin (TTX) (Fig. 2C), indicative of a direct synaptic connection (20).

Fig. 2.

AgRP neurons can directly inhibit Kiss-expressing cells in the ARH and AVPV. (A) Map of the viral construct along with a diagram of the targeted injection site and confirmation of transduced neurons in the arcuate. (Scale bar, 300 μm.) (B) Trace recording from an undefined (nonfluorescent) cell in the ARH that exhibited a light-evoked IPSC in the presence of CNQX and AP5 (red trace) and was blocked by the addition of BIC (black trace). Cells were chosen based on proximity of the soma to fluorescent AgRP fibers. Inset demonstrates fluorescent AgRP fibers in the ARH. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) (C) The light-evoked fast IPSC response (red trace, average of 10 sweeps) was abolished in the presence of TTX (black trace) and rescued upon addition of the K+ channel blocker, 4-AP (green trace). (D) Analysis of cell lysates harvested from recorded cells via PCR detection of: Kiss1, Pomc, and Th cDNA. Reverse-transcribed cDNA from the hypothalamus was used as a positive control, whereas hypothalamic RNA was tested as the negative control. Water blanks were also included. (E) Blind recording of unidentified cell in the AVPV that demonstrated a light-evoked response. Note, for all recordings, fibers were stimulated with 330 μW of blue light at varying frequencies and pulse widths. Whole-cell, patch-clamp recordings were performed in the presence of CNQX (10 μM) and AP5 (50 μM) and the evoked responses were blocked by BIC (30 μM). (Scale bar, 100 μm.)

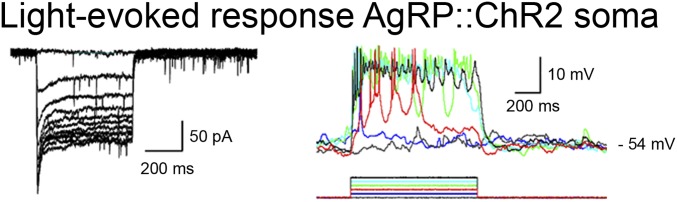

Fig. S1.

Proof of principle: blue light induces depolorization of AgRP::ChR2-expressing cells. Fluorescently labeled and ChR2-expressing AgRP neurons demonstrated a dose-dependent response to intensity of light exposure. Cells were recorded in both voltage clamp (Vhold = –60 mV; duration 1 s, from 33 to 330 μW; Left) and clamp mode (duration 1 s, from 33 to 198 μW; Right).

To determine whether photoactivation of AgRP neurons also inhibits Kiss1AVPV neurons, we recorded light-evoked GABAA-mediated IPSCs in slices containing the AVPV (Fig. 2E). We identified light-evoked IPSC currents that were bicuculline sensitive in 18 neurons. Seven of these neurons expressed Kiss1, as determined by post hoc transcription profiling. The light-evoked response was time locked to the light flash, occurring with a latency of 3–5 ms and jitter of 0.43 ± 0.11 ms (n = 7). TTX-evoked inhibition of these Kiss1AVPV-positive neurons was restored by 4-AP as in Fig. 2C.

The main purpose of the optogenetic experiments was to define the synaptic inputs and signaling properties of Kiss1ARH and Kiss1AVPV neurons. Our recordings were performed blind on cells neighboring fluorescent, ChR2-expressing, AgRP fibers. Post hoc single-cell RT-PCR of the harvested cell content following electrophysiological recordings was used to identify the recorded cells, but we did not quantify the number of Kiss1 neurons in either the ARH or AVPV that receive information from AgRP neurons. Nevertheless, our electrophysiological findings reveal direct, GABAergic connections from AgRP neurons to some Kiss1 neurons in both the ARH and AVPV.

AgRP Input to GnRH Neurons Is Likely Indirect.

We suspected that GnRH neurons might also receive synaptic input from AgRP neurons (21, 22) and again evaluated this connection using optogenetics. GABA signaling via the GABAA receptor has been shown to be excitatory on GnRH (23); hence, NPY or AgRP would need to provide the hypothesized inhibitory input. Regardless, we measured GABA signaling onto GnRH neurons as a marker of direct signaling from AgRP neurons to GnRH neurons. For this experiment, we generated mice containing both AgrpCre:GFP and GnrhGFP (24), which allowed us to virally transduce AgRP neurons with AAV1-EF1α-DIO-ChR2:mCherry virus and record from fluorescently labeled GnRH neurons (Fig. 3A). We did not observe light-evoked (1–10 Hz, 5- to 25-ms pulse width) GABAA responses in GnRH neurons (Fig. 3B) under conditions (i.e., high chloride internal solution, Vh = −60 mV) that would detect either excitatory or inhibitory GABA responses in GnRH neurons. Even with higher frequency stimulation (10 Hz), which we have shown is efficacious to release peptides (6), we did not see any direct inhibition of GnRH neurons. Considering that the synaptic connections between AgRP and GnRH neurons might be on distal dendrites rather than the soma (21), we tried clamping the cells at −90 mV to increase the driving force and hence the amplitude of the synaptic currents. We also tested sagittal-slice preparations to preserve the axonal projections from GnRH neurons to the median eminence (Fig. 3A). In total, we patched onto 57 GFP-labeled GnRH neurons and failed to identify either fast or slow (peptidergic) light-evoked responses under any of these conditions. As a positive control, we identified light-evoked responses in Kiss1AVPV neurons in the sagittal-slice preparation (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

There is not a direct connection between AgRP and GnRH neurons. (A) Sagittal diagram and matching fluorescent image indicating the location of AgRP neurons (red) and GnRH neurons (green). (B) Trace from whole-cell patched recording of fluorescently labeled GnRH soma during AgRP fiber stimulation (Vhold = −60 mV). Histology demonstrating GFP-expressing GnRH neurons and ChR2:mCherry-expressing AgRP fibers in the medial preoptic (MPO). (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (C) Light-evoked response from a neighboring neuron in the AVPV. Post hoc transcriptional profiling of the recorded cell in B confirmed expression of Kiss1 transcript.

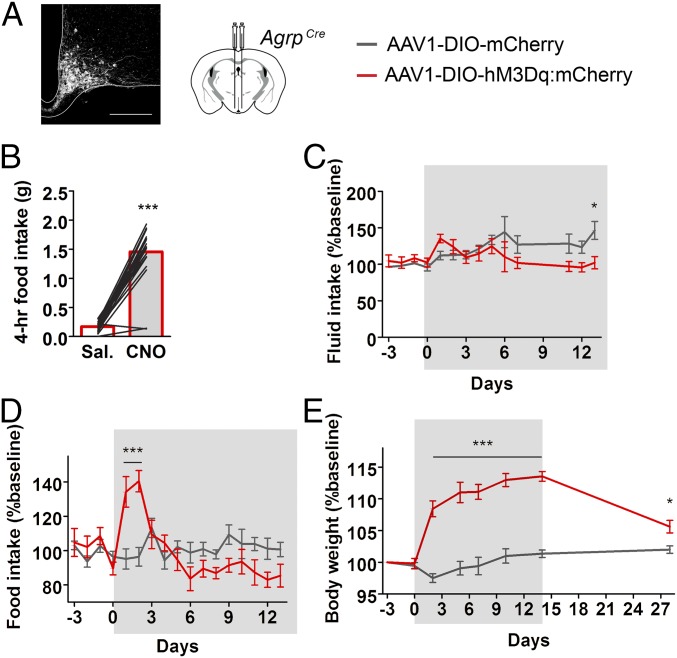

Chronic Activation of AgRP Neurons Using Chemogenetics.

Signaling from Kiss1ARH and Kiss1AVPV onto GnRH neurons is essential for normal reproductive function (25, 26); therefore, we predicted that chronic stimulation of inhibitory AgRP neurons in well-fed mice would impair fertility. To investigate this possibility, we virally transduced a cohort of AgrpCre:GFP female mice with a conditional stimulatory Gαq-coupled human M3 muscarinic DREADD receptor (AAV1-EF1α-DIO-hM3Dq:mCherry) or AAV1-EF1α-DIO-mCherry as control (Fig. 4A) (27). Following postoperative recovery, we confirmed that clozapine N-oxide (CNO) (1 mg/kg) could promote feeding during the light cycle (Fig. 4B) (28). To achieve nearly chronic activation, we administered CNO in the drinking water (29). This treatment (14 d) had a subtle effect on fluid consumption (Fig. 4C), transiently elevated food intake (Fig. 4D), and led to persistent weight gain (Fig. 4E). Food intake was only elevated during the first few days (Fig. 4D), presumably because AgRP signaling also decreases energy expenditure (28). After cessation of CNO treatment, body weight fell (Fig. 4E), revealing the persistent effect of CNO treatment. These data indicate that CNO in the drinking water promotes sustained, chronic AgRP-neuron activation.

Fig. 4.

Chronic activation of AgRP neurons using chemogenetics. (A) Experimental and control AgrpCre mice were transduced with a conditional viral vector expressing either an hM3Dq DREADD receptor fused to a fluorescent reporter or a fluorescent reporter. (A, Left) Histology of viral expression in AgRP neurons. (Scale bar, 200 μm.) (B) Prescreening: CNO-induced food intake (1 mg/kg i.p.). Animals included in the study consumed >1.0 g of food, 4 h post-CNO. (C–E) Chronic administration of CNO in the drinking water (gray highlight, administered at ∼5 mg/kg/day assuming an average body weight of 22 g and daily water intake of 3.5 mL). (C) Fluid intake change over time. mCherry (n = 7), hM3Dq (n = 5). Two-way ANOVA, main effect of interaction: F(13,140) = 2.26, P = 0.01; main effect of time: F(13,140) = 2.24, P = 0.02; main effect of experimental condition: F(1,140) = 5.60, P = 0.01; post hoc: day 14, *P < 0.05. (D) Food intake change over time. mCherry (n = 7), hM3Dq (n = 5). Two-way ANOVA, main effect of interaction: F(16,170) = 5.64, P < 0.0001; main effect of time: F(16,170) = 4.42, P < 0.0001; main effect of experimental condition: F(1,170) = 0.059, P = 0.44; post hoc: day 1, ***P < 0.001; day 2, ***P < 0.001. (E) Body weight change over time; before, during, and after the presentation of CNO in the drinking water. mCherry (n = 7–15), hM3Dq (n = 5–8). Two-way ANOVA, main effect of interaction: F(7,99) = 17.35, P < 0.0001; main effect of time: F(7,99) = 21.12, P < 0.0001; main effect of experimental condition: F(1,99) = 275.62, P < 0.0001; post hoc: days 2, 5, 7, 10, 14, ***P < 0.001; day 28, *P < 0.05.

Enhanced AgRP Signaling Attenuates Fertility.

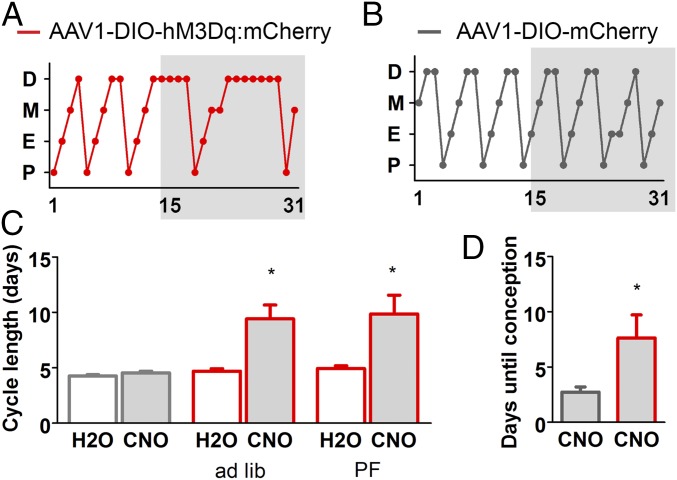

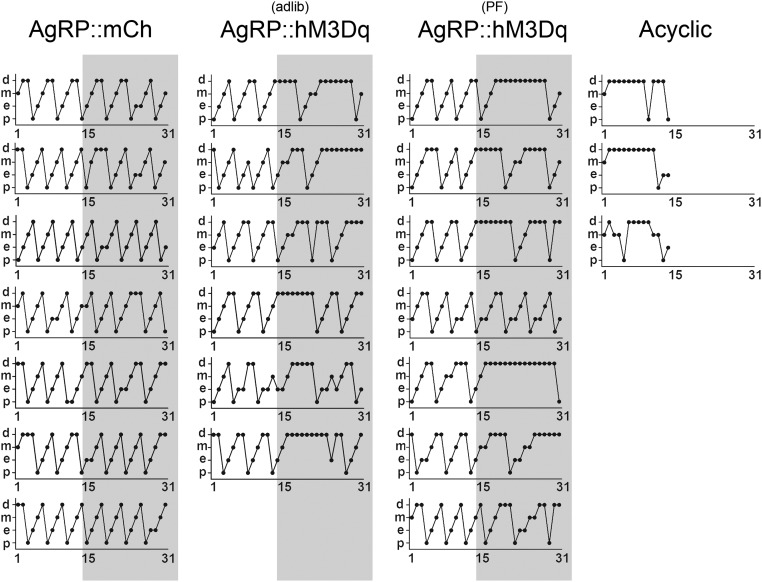

Using CNO in the drinking water, we evaluated the effect of chronic AgRP neuron activation on female fertility. Estrous-cycle length was monitored for 4 wk; a 2-wk baseline was compared with the subsequent 2-wk CNO treatment. Because CNO enhanced body weight of the hM3Dq-expressing mice, a second group of experimental mice was pair fed (PF) to the control mice. Fig. 5A shows a typical estrus cycle profile for experimental mice, whereas Fig. 5B shows a typical estrus cycle profile for the control group; the cycles of all of the mice in both groups are shown in Fig. S2. The estrous cycle of the hM3Dq-expressing mice increased from 4.8 ± 0.2 to 9.7 ± 1.0 d during CNO exposure, with most of the delay occurring in diestrus; in contrast, the cycle length of control females was unaffected by CNO; 4.3 ± 0.1 without CNO and 4.5 ± 0.2 d with CNO (Fig. 5C). Mice become pregnant during estrus; hence, doubling of cycle length significantly decreases fertility (30).

Fig. 5.

Chronic activation of AgRP impairs fertility in female mice. (A–D) Chronic administration of CNO in the drinking water (gray highlight indicates CNO treatment; administered in the drinking water as described in Fig. 4. (A and B) Cycle stage characterization of an experimental and control animal before and during the presentation of CNO in the drinking water. (C) Average length of time between proestrus; within subject comparisons before and during CNO treatment. H2O vs. CNO. Control group: paired two-tailed Student’s t test: H2O (M = 4.31, SD = 0.37) vs. CNO (M = 4.54, SD = 0.43): t(7) = 2.09, n.s. P = 0.075. Experimental group (ad libitum access): paired two-tailed Student’s t test: H2O (M = 4.70, SD = 0.54) vs. CNO (M = 9.42, SD = 3.07): t(5) = 3.86, *P = 0.012. Experimental group (pair fed): paired two-tailed Student’s t test: H2O (M = 4.93, SD = 0.67) vs. CNO (M = 9.86, SD = 4.49): t(6) = 4.88, *P = 0.019. (D) Fertility test: control and experimental animals were treated with CNO drinking water and mated with WT males. The latency from initial exposure to a male until conception is presented (assuming a gestation period of 20 d). mCherry vs. hM3Dq. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test: mCherry (n = 11; M = 2.73, SE = 0.47) vs. hM3Dq (n = 8; M = 7.63, SE = 2.10): t(17) = 2.64, *P = 0.02. D, diestrus; M, metestrus; E, estrus; P, proestrus.

Fig. S2.

Estrus cycle length of individual mice in the study. (A) Staged estrus cycles of individual mice. Three cohorts of animals were evaluated: (column 1) control group, AgrpCre mice transduced with a conditional mCh-expressing virus (AgRP::mCH); (column 2) experimental group, AgrpCre mice transduced with a conditional hM3Dq-expressing virus (AgRP::hM3Dq) given ad libitum access to food during CNO treatment; and (column 3) experimental group, same as column 2 but pair fed (PF) to baseline. Three animals failed to cycle within the first 2 wk (acyclic) and were excluded from the study.

To confirm that the delayed estrous-cycle length impaired fertility, female mice receiving CNO were paired with a sexually experienced male and CNO treatment was maintained for 5 wk (paired the day following first exposure to CNO). AgRP neuron-stimulated mice took longer to conceive (the length of time to parturition subtracted from the standard 20-d gestation); 7.6 ± 2.1 d for hM3Dq-expressing mice vs. 2.7 ± 0.5 d for controls (Fig. 5D). Another control group received normal drinking water instead of CNO; there was no effect of CNO on conception between these two control groups; H2O 2.6 ± 0.6 d vs. CNO 2.8 ± 0.9 d. Not all females in this study gave birth within the 5-wk trial: of 14 controls, 3 did not give birth; of 9 experimental mice, 1 did not give birth and 3 could not deliver pups due to dystocia. Contingency analysis does not support a difference between the percent of control vs. experimental mice that gave birth (Fisher’s exact test; P = 0.363). The 5-d delay in fertility is consistent with the delay observed in the estrous cycle and supports a role for enhanced AgRP activity in fertility impairment.

Discussion

Reproduction is metabolically demanding, especially in small mammals with large litters. By the end of lactation, a female mouse will nearly triple her food intake to successfully wean her pups (18). Thus, neurophysiological mechanisms detect deficits in energy reserves and inhibit the neuroendocrine axis to prevent pregnancy (2, 31). Here we show that starvation-sensitive AgRP neurons can attenuate reproduction by inhibiting neighboring Kiss1ARH and rostral Kiss1AVPV neurons. We did not observe a direct, GABAA-mediated connection between AgRP and GnRH neurons. The circuitry connecting both Kiss1ARH and Kiss1AVPV neurons to the neuroendocrine output GnRH is well established (6), and this circuit is likely responsible for attenuating fertility during metabolic deficiency. There may be additional sources of inhibition onto Kiss1 neurons during starvation, but the observation that ablation of AgRP neurons can restore fertility in leptin-deficient mice (15) argues that AgRP neurons are an important source of inhibition.

The critical starvation-related cue that initiates this neurophysiological inhibition of fertility remains controversial. Leptin is one signal that regulates reproduction. Mice that cannot make leptin (Lepob/ob) or respond to it (Leprdb/db) are infertile (32, 33) and leptin levels fall with the loss of adipose tissue during starvation (1, 34–36). Both AgRP and Kiss1 neurons are leptin sensitive (37); however, genetic loss of leptin signaling in either of these populations does not affect fertility (38, 39) and restoration of leptin in calorically restricted rodents does not restore reproduction (40). A critical experiment is to determine whether leptin signaling only in AgRP neurons is sufficient to maintain fertility in Lepdb/db mice.

Fasting and starvation activate AgRP neurons (12, 41) and Lepob/ob mice lacking the ability to make leptin have high AgRP neuronal activity because leptin normally inhibits AgRP neuron activity (42). The activated AgRP neurons release AgRP, NPY, and GABA (11–14). We show here that GABA released by AgRP neurons has direct, inhibitory actions on Kiss1 neurons, but the two peptides may also contribute. Mice lacking the ability to make NPY partially restores fertility in Lepob/ob mice (43) and similarly, disruption of melanocortin signaling (AgRP/Mc4R) partially restores fertility in Lepdb/db (22).

We did not observe any fast (GABAergic) or slow (peptidergic) input to GnRH neurons from AgRP neurons. Findings in the literature reveal that GnRH neurons are sensitive to a melanocortin agonist (22), GnRH neurons and fibers are in close apposition to NPY-expressing fibers that originate in the ARH, and GnRH fibers and nerve terminals express the NPY Y1 receptor in lactating rats (21). However, when we stimulated ChR2-expressing AgRP axons at 10 Hz, which we have shown effectively releases neuropeptides from ARH neurons (6), no AgRP- or NPY-mediated hyperpolarization of GnRH neurons was observed.

We attempted to mimic the effect of starvation by artificially activating AgRP neurons over an extended period. We demonstrated that this activation approach extends the estrous cycle by twofold and increased the time to pregnancy by 5 d but it did not totally block fertility. Although the CNO treatment protocol that we used had a prolonged biological effects on body weight, the magnitude of AgRP neuron activation achieved during starvation or in Lepob/ob mice may be even greater and have more profound effects on fertility. Previous work demonstrated that both hM3Dq- and ChR2-mediated stimulation can evoke immediate early Fos expression in AgRP neurons (28, 44). However, we have shown that specific frequencies of laser stimulation can modulate the differential release of peptide vs. fast transmitter from ChR2-expressing neurons (6). The more quantitative approach of activating AgRP neurons with ChR2 is not practical for the long periods of time needed to study fertility.

During starvation, impaired gonadotropin release leads to hypogonadism and infertility (1–3). The mechanism and metabolic cues responsible for this adaptation remain unknown. Our results demonstrate that starvation-sensitive AgRP neurons are sufficient to attenuate fertility by way of directly inhibiting Kiss1ARH and Kiss1AVPV neurons within the neuroendocrine reproductive axis. This finding contributes to a growing body of evidence related to the functional diversity of AgRP neurons. During periods of negative-energy balance activation of AgRP neurons not only provides a strong motivation to seek and consume food (45), but also helps to conserve energy by inhibiting energy-demanding physiological processes such as reproduction.

Methods

Animals.

Animal care and genetic lines.

All experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Washington and at the Oregon Health and Science University and were in accordance with NIH guidelines. The genetic mouse lines: AgrpCre:GFP, Kiss1Cre:GFP, and GnrhGFP have been characterized (24, 46, 47); AgrpCre:GFP and Kiss1Cre:GFP lines were backcrossed to C57BL/6 background more than six generations. We used a combination of male and female animals in this study. Young- to mature-adult animals (5–24 wk of age) were used in these studies as indicated in the experiments below.

Diphtheria toxin ablation.

A female heterozygous AgrpDTR/+ mouse (16) was bred with a homozygous male Kiss1Cre/Cre mouse. When a litter was born, all pups were injected between postnatal day 2 (PN2) and PN7 with DT (75 ng per pup, s.c.). DT was dissolved in normal saline and diluted to 0.5 ng/μL. At weaning, mice were genotyped for the AgrpDTR allele. All mice were presumed heterozygous Kiss1Cre/+. Those expressing AgrpDTR are “neonatally AgRP-neuron ablated.” Those lacking the DTR are controls. At 12.5 wk of age, the females were ovariectomized and hypothalamic slices were prepared for electrophysiological recording 2 wk following gonadectomy.

Stereotaxic Injections and Tissue Preparation.

Stereotaxic surgery and injection coordinates.

For precise coordinate mapping, mice were anesthetized and positioned onto a small animal stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments). Sustained anesthetic was delivered via nose cone (1.5–2% isoflurane) throughout the procedure, and body temperature was maintained with a heating pad. Either a Hamilton 88000 syringe or pulled-glass capillary was used to inject the target brain regions, bilaterally. The injection coordinates used are as follows: arcuate hypothalamic nucleus (ARH; adult)/bregma –1.25, lateral ±0.25, ventral –5.8; (ARH; 3–4 wk)/bregma –1.1, lateral ±0.25, ventral –5.7.

Viruses and neuronal tracers.

AAV serotype 1 viruses (AAV1-Ef1α-DIO-ChR2:YFP, AAV1-Ef1α-DIO-ChR2:mCherry, and AAV1-Ef1α-DIO-hM3Dq:mCherry) were generated at the University of Washington as described (48). We did not observe side effects in animals injected with any of these AAV1 viruses (injected 500 nL of virus, ∼109 particles per microliter). Behavioral tests began at least 3 wk after surgery.

Histology.

Mice were anesthetized and transcardially perfused with saline, followed by 4% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB). For immunohistochemistry, brains were postfixed (6 h), washed, cryoprotected in 0.1 M PB with 30% (wt/vol) sucrose, embedded in OCT and frozen at –80 °C. Thirty-micrometer floating sections were stained for mCherry and Fos with the primary antibodies: rabbit anti-DsRed (Clontech 632496; diluted 1:1,000) or goat anti-Fos (Santa Cruz SC-52-G; diluted 1:300). Antibodies were diluted in 0.1 M PB with 0.1% Triton and 2% (vol/vol) donkey serum and developed overnight at 4 °C.

Electrophysiology.

Slice preparation.

Slices were prepared as described (49). Mice were killed quickly by decapitation at 10:00–11:00 AM. The brain was rapidly removed from the skull and a block containing the basal hypothalamus (BH) or preoptic area (POA) was immediately dissected. The block was submerged in cold (4 °C) oxygenated (95% O2, 5% CO2) high-sucrose cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) (in millimoles): 208 sucrose, 2 KCl, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 2 MgSO4, 1 MgCl2, 10 Hepes, pH 7.3, 300 mOsm). Coronal or sagittal slices (250 µm) containing the AVPV and/or POA were cut on a vibratome (Leica VT1000S) during which time (10 min) the slices were bathed in high-sucrose CSF at 4 °C. The slices were then transferred to an auxiliary chamber in which they were kept at room temperature (25 °C) in artificial CSF (aCSF) consisting of the following (in millimoles): 124 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2.6 NaH2PO4, 2 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, pH 7.3, 310 mOsm until recording (recovery for 2 h). A single slice was transferred to the recording chamber mounted on an Olympus BX51W1 upright microscope (see below). The slice was continually perfused (Gilsen Minipuls 2 pump) with warm (34 °C), oxygenated aCSF and all drug solutions at 1.5 mL/min. Drug solutions were prepared in 20-mL syringes by diluting the appropriate stock solution with aCSF, and the flow was switched via a three-way stopcock.

Whole-cell, voltage, and current-clamp recordings.

Whole-cell, patch-clamp recordings were conducted with the use of an Olympus BX51 (Olympus) equipped with epifluorescence (FITC and mCherry filter sets) and IR-differential interference contrast video microscopy (50).

Patch pipettes were made of borosilicate glass (1.5 mm outer diameter, thin wall with filament; World Precision Instruments) and pulled using a Brown/Flaming puller (Sutter Instrument, model P-97) and filled with K+-gluconate or with high chloride internal solution (2.5–4 MΩ resistance). K+-gluconate internal solution contained the following solution (in millimoles): 128 potassium gluconate, 10 NaCl, 1 MgCl2, 11 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 2 ATP, 0.25 GTP; and high chloride internal solution contained the following solution (in millimoles): 140 KCl, 5 MgCl2 ·6H2O, 1 MgCl2, 0.1 EGTA, 10 Hepes, 5 K2-ATP, 0.35 Na3-GTP (pH was adjusted to 7.3–7.4 with KOH; 290–295 mOsm). The GABAA IPSCs were recorded as inward currents with the high chloride internal solution. An Axopatch 200A amplifier, Digidata 1322A Data Acquisition System and pCLAMP software (version 9.2; Molecular Devices) were used for data acquisition and analysis. Input resistance, series resistance, and membrane capacitance were monitored throughout the experiments. Only cells with stable series resistance (<30 MΩ; <20% change) and an input resistance >500 MΩ were used for analysis. The access resistance was 80% compensated and the liquid junction potential was corrected. For optogenetic stimulation, a light-induced response was evoked using a light-emitting diode (LED) 470 nm blue light source controlled by a variable 2A driver (ThorLabs) with the light path delivered directly through an Olympus 40× water-immersion lens. We varied the stimulation parameters (frequency and pulse width) to evoke both fast amino acid and slow neuropeptide release as previously published (6).

AgRP ablation study.

Miniature IPSCs (mIPSCs) were recorded with a high chloride internal solution in the presence of TTX (1 μM), CNQX (20 μM), and AP5 (50 μM). Cell membrane potentials were voltage clamped at –60 mV. IPSC traces were filtered at 10 kHz and acquired at a sampling rate of 5 kHz. The mIPSC data were analyzed with MiniAnalysis software (Synaptosoft).

Drugs.

All chemicals were purchased from Calbiochem unless otherwise specified. (2R)-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (d-AP5), and 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) were all purchased from Tocris. (–)-Bicuculline methiodide was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. TTX was purchased from Alomone Labs and dissolved in H2O.

Physiology.

Prescreening.

Numerous studies using viral targeting as a means of activating AgRP neurons have found that the efficiency (number of cells transduced) correlates with the magnitude of the feeding response when activated (28, 44). Based on this finding, we used a prescreening criteria to select animals that consumed at least 1 g of food 4 h after administration of CNO (1 mg/kg).

Estrous cycling.

Females were individually housed in a noise-free room (12/12 h light/dark cycle) and only handled by the investigator during cycle tracking. Daily vaginal lavage samples, collected with sterile PBS, were acquired within the first 2 h of the light cycle. Cells were scored (blinded) under light microscopy for the presence of cornified epithelial cells, leukocytes, and nucleated epithelial cells. The loss of leukocytes and presence of an abundance of nucleated cells was scored as proestrus, whereas the transition to primarily cornified epithelial cells was scored as estrus.

CNO administration.

CNO was obtained from the National Institute of Mental Health Chemical Synthesis and Drug Supply Program (catalog no. C-929). The dry chemical was dissolved in DMSO (125 μg/μL; concentrated stock). Drinking water experiments: CNO treatment (5 mg/kg/day). The animals in this study had an average starting weight of 22 g and consumed ∼3.5 mL of water per day. The concentrated CNO stock was diluted to 31.4 μg/mL in drinking water (containing 0.025% DMSO). CNO water was made fresh and changed every other day. For IP injections, CNO was diluted to 0.1 mg/mL in normal saline and injected at a concentration of 1 mg/kg body weight.

Postrecording Single-Cell PCR.

Following whole-cell recordings, the cytoplasm of the patched cell was harvested by applying negative pressure to gently aspirate the cell content into the tip of the recording pipette. The cell content was expelled into a 600-μL tube containing 1× Superscript III buffer (Invitrogen), 10 mM DTT, 15 units RNasin (Promega) and diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water in a 5 μL volume and stored at –80 °C until further processing. RNA transcripts in the harvested lysate were reverse transcribed and PCR was performed as described (51) using the following primer sets: Kiss1 5′-TGCTGCTTCTCCTCTGT and 5′-ACCGCGATTCCTTTTCC; Pomc 5′-GGAAGATGCCGAGATTCTGC and 5′-TCCGTTGCCAGGAAACAC; and Th 5′-CAGCCCTACCAAGATCAAAC and 5′-GTGTACGGGTCAAACTTCAC.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad’s Prism software. A P value of 0.05 was the threshold for significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001), and all error bars represent SEMs. n values represent either individual mice or number of cells as indicated in the text. Data were gathered from at least three independent experiments. All of the datasets evaluated in the revised manuscript passed the D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test.

Acknowledgments

We thank K. Kafer, M. Chiang, M. A. Bosch, and U. V. Navarro for technical assistance with surgeries and maintaining the mouse colonies; B. C. Jarvie for preliminary circuit mapping study; Drs. D. M. Durnam, M. A. Patterson, and R. A. Steiner for their careful reading and editorial revisions; Drs. C. F. Elias and N. Bellefontaine for their work on the female fertility study; and the entire R.D.P. laboratory for helpful discussions and critiques. This work was supported by funds from the Hilda Preston Davis Foundation (S.L.P.) and National Institutes of Health Grants R01DK068098, R01NS038809, and R01NS043330 (to M.J.K. and O.K.R.) and R01DA024908 (to R.D.P.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1621065114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.De Souza MJ, Metzger DA. Reproductive dysfunction in amenorrheic athletes and anorexic patients: A review. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1991;23(9):995–1007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cagampang FR, Maeda K, Yokoyama A, Ota K. Effect of food deprivation on the pulsatile LH release in the cycling and ovariectomized female rat. Horm Metab Res. 1990;22(5):269–272. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1004900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron JL, Nosbisch C. Suppression of pulsatile luteinizing hormone and testosterone secretion during short term food restriction in the adult male rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) Endocrinology. 1991;128(3):1532–1540. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-3-1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Popa SM, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. The role of kisspeptins and GPR54 in the neuroendocrine regulation of reproduction. Annu Rev Physiol. 2008;70:213–238. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navarro VM, et al. Regulation of NKB pathways and their roles in the control of Kiss1 neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the male mouse. Endocrinology. 2011;152(11):4265–4275. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qiu J, et al. High-frequency stimulation-induced peptide release synchronizes arcuate kisspeptin neurons and excites GnRH neurons. eLife. 2016;5:e16246. doi: 10.7554/eLife.16246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith JT, Cunningham MJ, Rissman EF, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. Regulation of Kiss1 gene expression in the brain of the female mouse. Endocrinology. 2005;146(9):3686–3692. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gottsch ML, et al. Molecular properties of Kiss1 neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the mouse. Endocrinology. 2011;152(11):4298–4309. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rometo AM, Krajewski SJ, Voytko ML, Rance NE. Hypertrophy and increased kisspeptin gene expression in the hypothalamic infundibular nucleus of postmenopausal women and ovariectomized monkeys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(7):2744–2750. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han SY, McLennan T, Czieselsky K, Herbison AE. Selective optogenetic activation of arcuate kisspeptin neurons generates pulsatile luteinizing hormone secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(42):13109–13114. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512243112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Horvath TL, Bechmann I, Naftolin F, Kalra SP, Leranth C. Heterogeneity in the neuropeptide Y-containing neurons of the rat arcuate nucleus: GABAergic and non-GABAergic subpopulations. Brain Res. 1997;756(1–2):283–286. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hahn TM, Breininger JF, Baskin DG, Schwartz MW. Coexpression of Agrp and NPY in fasting-activated hypothalamic neurons. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1(4):271–272. doi: 10.1038/1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowley MA, et al. Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through a neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature. 2001;411(6836):480–484. doi: 10.1038/35078085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Broberger C, Johansen J, Johansson C, Schalling M, Hökfelt T. The neuropeptide Y/agouti gene-related protein (AGRP) brain circuitry in normal, anorectic, and monosodium glutamate-treated mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(25):15043–15048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.15043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu Q, Whiddon BB, Palmiter RD. Ablation of neurons expressing agouti-related protein, but not melanin concentrating hormone, in leptin-deficient mice restores metabolic functions and fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(8):3155–3160. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1120501109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luquet S, Perez FA, Hnasko TS, Palmiter RD. NPY/AgRP neurons are essential for feeding in adult mice but can be ablated in neonates. Science. 2005;310(5748):683–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1115524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu Q, Howell MP, Cowley MA, Palmiter RD. Starvation after AgRP neuron ablation is independent of melanocortin signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(7):2687–2692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712062105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phillips CT, Palmiter RD. Role of agouti-related protein-expressing neurons in lactation. Endocrinology. 2008;149(2):544–550. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyden ES, Zhang F, Bamberg E, Nagel G, Deisseroth K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(9):1263–1268. doi: 10.1038/nn1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cruikshank SJ, Urabe H, Nurmikko AV, Connors BW. Pathway-specific feedforward circuits between thalamus and neocortex revealed by selective optical stimulation of axons. Neuron. 2010;65(2):230–245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li C, Chen P, Smith MS. Morphological evidence for direct interaction between arcuate nucleus neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons and gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons and the possible involvement of NPY Y1 receptors. Endocrinology. 1999;140(11):5382–5390. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Israel DD, et al. Effects of leptin and melanocortin signaling interactions on pubertal development and reproduction. Endocrinology. 2012;153(5):2408–2419. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Herbison AE, Moenter SM. Depolarising and hyperpolarising actions of GABA(A) receptor activation on gonadotrophin-releasing hormone neurones: Towards an emerging consensus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23(7):557–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02145.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suter KJ, et al. Genetic targeting of green fluorescent protein to gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons: Characterization of whole-cell electrophysiological properties and morphology. Endocrinology. 2000;141(1):412–419. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.1.7279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.d’Anglemont de Tassigny X, et al. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism in mice lacking a functional Kiss1 gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(25):10714–10719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704114104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Roux N, et al. Hypogonadotropic hypogonadism due to loss of function of the KiSS1-derived peptide receptor GPR54. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(19):10972–10976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834399100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Armbruster BN, Li X, Pausch MH, Herlitze S, Roth BL. Evolving the lock to fit the key to create a family of G protein-coupled receptors potently activated by an inert ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(12):5163–5168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700293104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krashes MJ, et al. Rapid, reversible activation of AgRP neurons drives feeding behavior in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(4):1424–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI46229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jain S, et al. Chronic activation of a designer Gq-coupled receptor improves β cell function. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(4):1750–1762. doi: 10.1172/JCI66432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moss ML. Experimental alteration of sutural area morphology. Anat Rec. 1957;127(3):569–589. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091270307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ball ZB, Barnes RH, Visscher MB. The effects of dietary caloric restriction on maturity and senescence, with particular reference to fertility and longevity. Am J Physiol. 1947;150(3):511–519. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1947.150.3.511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swerdloff RS, Batt RA, Bray GA. Reproductive hormonal function in the genetically obese (ob/ob) mouse. Endocrinology. 1976;98(6):1359–1364. doi: 10.1210/endo-98-6-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batt RAL, et al. Investigation into the hypogonadism of the obese mouse (genotype ob/ob) J Reprod Fertil. 1982;64(2):363–371. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0640363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kennedy GC, Mitra J. Body weight and food intake as initiating factors for puberty in the rat. J Physiol. 1963;166:408–418. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1963.sp007112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frisch RE, McArthur JW. Menstrual cycles: Fatness as a determinant of minimum weight for height necessary for their maintenance or onset. Science. 1974;185(4155):949–951. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4155.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erickson JC, Ahima RS, Hollopeter G, Flier JS, Palmiter RD. Endocrine function of neuropeptide Y knockout mice. Regul Pept. 1997;70(2–3):199–202. doi: 10.1016/s0167-0115(97)01007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qiu J, et al. Insulin excites anorexigenic proopiomelanocortin neurons via activation of canonical transient receptor potential channels. Cell Metab. 2014;19(4):682–693. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Donato J, Jr, et al. Leptin’s effect on puberty in mice is relayed by the ventral premammillary nucleus and does not require signaling in Kiss1 neurons. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(1):355–368. doi: 10.1172/JCI45106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van de Wall E, et al. Collective and individual functions of leptin receptor modulated neurons controlling metabolism and ingestion. Endocrinology. 2008;149(4):1773–1785. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.True C, Kirigiti MA, Kievit P, Grove KL, Smith MS. Leptin is not the critical signal for kisspeptin or luteinising hormone restoration during exit from negative energy balance. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23(11):1099–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Y, Lin YC, Kuo TW, Knight ZA. Sensory detection of food rapidly modulates arcuate feeding circuits. Cell. 2015;160(5):829–841. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shutter JR, et al. Hypothalamic expression of ART, a novel gene related to agouti, is up-regulated in obese and diabetic mutant mice. Genes Dev. 1997;11(5):593–602. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.5.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Erickson JC, Hollopeter G, Palmiter RD. Attenuation of the obesity syndrome of ob/ob mice by the loss of neuropeptide Y. Science. 1996;274(5293):1704–1707. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5293.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aponte Y, Atasoy D, Sternson SM. AGRP neurons are sufficient to orchestrate feeding behavior rapidly and without training. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14(3):351–355. doi: 10.1038/nn.2739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Padilla SL, et al. Agouti-related peptide neural circuits mediate adaptive behaviors in the starved state. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(5):734–741. doi: 10.1038/nn.4274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanz E, et al. Fertility-regulating Kiss1 neurons arise from hypothalamic POMC-expressing progenitors. J Neurosci. 2015;35(14):5549–5556. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3614-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Popa SM, et al. Redundancy in Kiss1 expression safeguards reproduction in the mouse. Endocrinology. 2013;154(8):2784–2794. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gore BB, Soden ME, Zweifel LS. Manipulating gene expression in projection-specific neuronal populations using combinatorial viral approaches. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2013;4(435):4.35.1–4.35 20. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0435s65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang C, et al. Molecular mechanisms that drive estradiol-dependent burst firing of Kiss1 neurons in the rostral periventricular preoptic area. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2013;305(11):E1384–E1397. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00406.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qiu J, Fang Y, Rønnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Leptin excites proopiomelanocortin neurons via activation of TRPC channels. J Neurosci. 2010;30(4):1560–1565. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4816-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bosch MA, Tonsfeldt KJ, Rønnekleiv OK. mRNA expression of ion channels in GnRH neurons: Subtype-specific regulation by 17β-estradiol. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;367(1-2):85–97. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2012.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]