Significance

The basis of protein-folding cooperativity and stability elicits a variety of opinions, as does the existence and importance of possible residual structure in the denatured state. We examine these issues in a protein that is striking in its dearth of hydrophobic burial and its lack of canonical α and β structures, while having a low sequence complexity with 46% glycine. Unexpectedly, the protein’s folding behavior is similar to that observed for typical globular proteins. This enigma forces a reexamination of the possible combination of factors that can stabilize a protein.

Keywords: protein folding, cooperativity, kinetics, PP2, hydrogen bonding

Abstract

The burial of hydrophobic side chains in a protein core generally is thought to be the major ingredient for stable, cooperative folding. Here, we show that, for the snow flea antifreeze protein (sfAFP), stability and cooperativity can occur without a hydrophobic core, and without α-helices or β-sheets. sfAFP has low sequence complexity with 46% glycine and an interior filled only with backbone H-bonds between six polyproline 2 (PP2) helices. However, the protein folds in a kinetically two-state manner and is moderately stable at room temperature. We believe that a major part of the stability arises from the unusual match between residue-level PP2 dihedral angle bias in the unfolded state and PP2 helical structure in the native state. Additional stabilizing factors that compensate for the dearth of hydrophobic burial include shorter and stronger H-bonds, and increased entropy in the folded state. These results extend our understanding of the origins of cooperativity and stability in protein folding, including the balance between solvent and polypeptide chain entropies.

The basis of protein-folding stability and cooperativity remains a topic of great interest (1, 2). Most studies have focused on proteins with hydrophobic cores containing α-helices and β-sheets. Here, we study the folding of snow flea antifreeze protein (sfAFP), a globular protein that lacks these features. The 81-residue protein has a novel fold that is distinct from other proteins (3–6), containing only polyproline 2 (PP2) helices and turns with a core filled with H-bonds and no hydrophobic groups (Fig. 1).

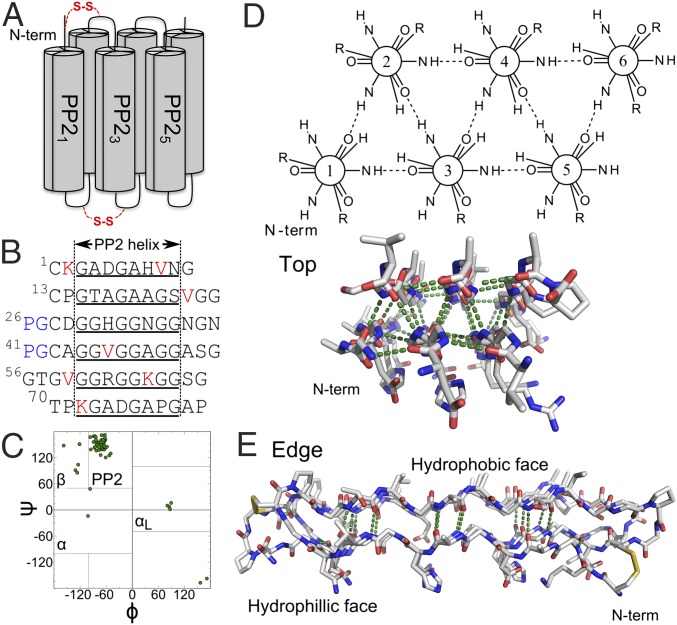

Fig. 1.

sfAFP structure (PDB ID code 2PNE). (A) Connectivity with the disulfide bonds is noted in red. (B) Sequence with helical regions (underlined), valines and lysines (red), and the two PG turns (blue). (C) Ramachandran map of native structure with four major basins noted. (D) Top and (E) edge view highlighting the internal H-bond network and the flat hydrophilic and hydrophobic faces.

The H-bond network between the PP2 helices (6), PP21–6, requires close packing, which would be precluded by the presence of a Cβ atom. Thus, the PP2 helices are defined by glycine (Gly) repeats (GXX or GGX, where X is any other amino acid), which enable the hydrogen-bond network. As a consequence, the sfAFP molecule has a low-complexity glycine-rich sequence [37/81 Gly residues, or 46%; typical is 6, or 7% (7)]. The sfAFP core is well packed with essentially no interior void volumes, even when probed using a 0.5-Å radius sphere (8). sfAFP also contains two disulfide bonds, C1–C28 and C13–C43.

Notably, no side chains are buried in sfAFP’s core (2). All 12 hydrophobic side chains (V4, K2, and P6) are surface exposed. Upon folding, sfAFP buries about 20 Å2·res−1 of hydrophobic surface area compared with an average of 50 Å2·res−1 for a set of 34 proteins of similar size (Fig. 2A). The difference equates to a decrease in stability of ∼1 or 1.4 kcal·mol−1·res−1, assuming a surface tension coefficient of γ ∼ 34 or 47 cal·mol−1·Å−2 based on classical (9) or Flory–Huggins theory (10), respectively. Even the lower bound of 1 kcal·mol−1·res−1 represents a significant stability loss, and it is not obvious which energetic terms could compensate for the reduction in hydrophobic burial.

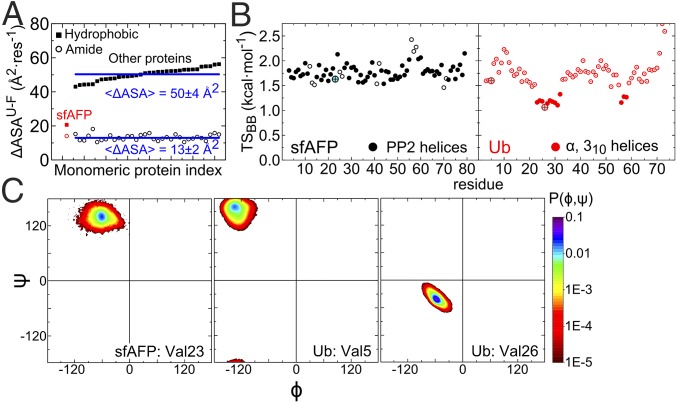

Fig. 2.

Properties of sfAFP and other proteins. (A) Hydrophobic and amide surface burial for sfAFP and similar-sized proteins. The calculation of sfAFP’s hydrophobic (■) and amide burial (○) assumes an unfolded state containing the two disulfide bonds (values increase by 29–30% when the disulfide bonds are removed). (B) Native-state backbone entropy for sfAFP and ubiquitin (Ub). Larger circles denote residues highlighted in C. (C) Ramachandran probability distributions from MD simulations for a valine in a PP2 helix (sfAFP) and in α and β structures (Ub).

Because hydrophobic burial is generally regarded as the basis of protein stability and folding cooperativity (11), we investigated sfAFP’s folding behavior. We characterize the stability and folding kinetics using circular dichroism (CD), fluorescence, and small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS). We find that sfAFP folds in a manner consistent with cooperative two-state folding with an energy surface dominated by the native and unfolded states. We propose that an unusual match between the dihedral angle propensities in the unfolded state ensemble and the secondary structure of the native state, increased native state backbone entropy, and stronger native state H-bonds are major contributors to the stability of the protein molecule.

Results

Thermal Denaturation of sfAFP.

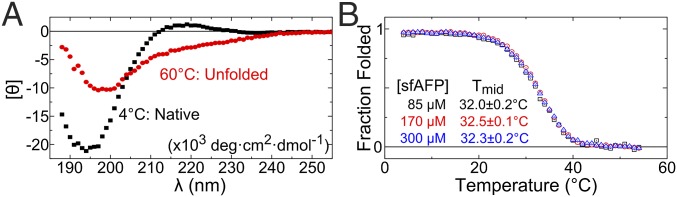

sfAFP was prepared using total chemical synthesis (12) with the two disulfide bonds formed at all times, except for the SAXS measurements. The CD spectrum at 4 °C, pH 8.0, is characteristic of PP2 helices, having a deep minimum at 195 nm and a positive peak at 217 nm (Fig. 3A). The positive peak disappeared upon heating to 60 °C and was restored upon overnight incubation at 4 °C. The unfolded CD spectrum is typical of what is observed in other proteins upon thermal denaturation. Although often termed “random coil,” this state represents an ensemble of backbone geometries with the (ϕ,ψ) dihedral angles predominantly in the PP2 basin and lesser populations in the αR, αL, and β basins (13–16).

Fig. 3.

Thermal denaturation of sfAFP. (A) CD spectra of folded (4 °C, black squares) and unfolded sfAFPH32W (60 °C, red circles). (B) Normalized thermal denaturation as a function of protein concentration for WT sfAFP.

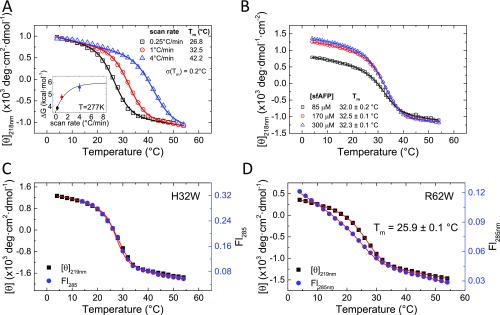

Thermal denaturation produced a sigmoidal curve with a midpoint Tmid of 32.5 ± 0.2 °C at a thermal ramp rate of 1 °C·min−1. The thermal transition was independent of protein concentration over a range of 85–300 µM (Fig. 3B and Fig. S1B), indicating that the protein remained monomeric over the concentration range studied. Faster thermal ramps brought forth a marked increase in Tmid, being 16 °C higher at a ramp rate of 4 °C·min−1 compared with 0.25 °C·min−1 (Fig. S1A). The increased stability is a manifestation of the unfolded state having less time to fully equilibrate due to slow unfolding (ku ∼ 10−5 s−1 at 4 °C) and cis/trans isomerization for the two cis and four trans Xaa-Pro peptide bonds in the native fold (2).

Fig. S1.

Thermal denaturation of tryptophan variants of sfAFP monitored using CD and Trp fluorescence. (A) Denaturation at different rates of temperature increase. (Inset) ΔG calculated at 277 K from the fits of the three different scan rates and assuming a change in heat capacity of ΔCp = 0.408 kcal·mol−1·K−1 (23). Extrapolation to an infinite scan rate is made by fitting the calculated parameters to a single-exponential model (Table S1). (B) Thermal denaturation as a function of protein concentration for WT sfAFP exhibits similar transition and baseline behavior (potential concentration scaling error). Thermal denaturation for H32W (C) and R62W (D) exhibits concurrent changes in CD and Fl as the temperature is increased at a rate of 1 °C⋅min−1. Steep fluorescent baselines have been observed in other two-state proteins as well, for example, CI2 (19). Due to the steepness of the native baseline in the fluorescence transition, the two datasets for R62W are simultaneously fit with the same Tm, ΔH, and ΔCp.

In the unfolded state, Xaa-Pro peptide bonds isomerize on the minute timescale (17) and equilibrate with a ratio of [trans]/[cis] ∼ 5, depending on the neighbor’s identity (18). The net reduction in stability due to this isomerization effect is the sum of individual values, ΔGcis-trans = 1.4 + 1.3 + 0.08 + 0.07 + 2·0.04 = 2.9 kcal·mol−1 (18). Although the nonequilibrium caused by the prolines compromises the validity of obtaining thermodynamic quantities, we have fit the transition at different temperature ramps and extrapolated the parameters to the limit of an infinitely fast ramp where isomerization in the unfolded state can be ignored (Fig. S1A, Inset). After extrapolation, we find that ΔH, TΔS, and ΔG = 38 ± 3, 32 ± 3, and 5.9 ± 0.6 kcal·mol−1, respectively, at T = 4 °C (Table S1).

Table S1.

Thermodynamic properties of sfAFP derived from thermal denaturation at different thermal ramp rates

| ΔT/Δt, °C/min | Tmid, °C | ΔH(Tmid), kcal·mol−1 | ΔS(Tmid), cal·mol−1·K−1 | ΔH(4 °C),* kcal·mol−1 | ΔS(4 °C),* cal·mol−1·K−1 | ΔG(4 °C),* kcal·mol−1 |

| 0.25 | 26.8 ± 0.2 | 56.1 ± 1.9 | 187 ± 6 | 46.5 ± 2.0 | 154 ± 7 | 3.89 ± 0.15 |

| 1 | 32.5 ± 0.2 | 57.3 ± 1.9 | 188 ± 6 | 45.6 ± 2.0 | 147 ± 7 | 4.78 ± 0.20 |

| 4 | 42.2 ± 0.2 | 54.1 ± 1.9 | 172 ± 6 | 38.6 ± 2.1 | 119 ± 7 | 5.57 ± 0.29 |

| ∞ | 38.1 ± 3.0† | 116 ± 12† | 5.92 ± 0.56† |

Fitting thermal melts used a fixed ΔCp = 0.408 kcal·mol−1·K−1, which is calculated from ref. 23. See SI Methods for further details.

ΔS(4 °C) and ΔG(4 °C) are obtained by fitting the thermal denaturation data referenced to Tref = 4 °C to minimize error propagation. ΔH(4 °C) is then calculated from ΔG(4 °C) + Tref·ΔS(4 °C).

Monitoring Denaturation with Multiple Probes.

To permit the monitoring of folding using both CD and fluorescence, two sfAFP analogs were prepared, sfAFPH32W and sfAFPR62W. Thermal denaturation measurements indicated that the analogs had similar stability to wild-type sfAFP (Tmid = 27.6 ± 0.1 and 25.9 ± 0.1 °C for sfAFPH32W and sfAFPR62W, respectively, versus Tmid = 32.5 ± 0.2 °C for WT sfAFP at a thermal ramp rate of 1 °C·min−1) (Fig. S1 C and D). For the Trp variants, the CD219nm and fluorescence signals (λexcite = 285 nm) changed concurrently with temperature and yielded the same Tmid values. This equivalence is consistent with a cooperative folding transition, as fluorescence is a local probe of the Trp environment, whereas CD219nm reports on the global formation of the PP2 helices. This finding provides initial evidence that the free-energy surface is well approximated near the folding midpoint as a double well potential with an unfolded state and a folded state.

Folding Kinetics and Cooperativity.

Kinetic measurements were conducted on sfAFPR62W to determine whether the energy landscape was approximated as a double well potential under strongly folding and unfolding conditions. The CD and fluorescence signals were simultaneously acquired at 4 °C in a CD spectrometer using the same wavelength (λ = 226 nm; Fig. 4A and Fig. S2) and guanidinium chloride (GdmCl) as a denaturant. Above 4 M GdmCl, unfolding rates were measured using a stopped-flow apparatus monitoring only fluorescence. Measuring folding rates independent of nonnative Pro isomers required “double-jump” measurements (17). During refolding, the CD and fluorescence signals tracked each other across different folding conditions. There was no evidence of a lag phase indicative of a folding intermediate, nor was any measurable subsecond change in CD amplitude observed before the first time point. The lack of a “burst” phase indicates that no measureable amount of secondary structure forms in a kinetic step before the folding to the native state.

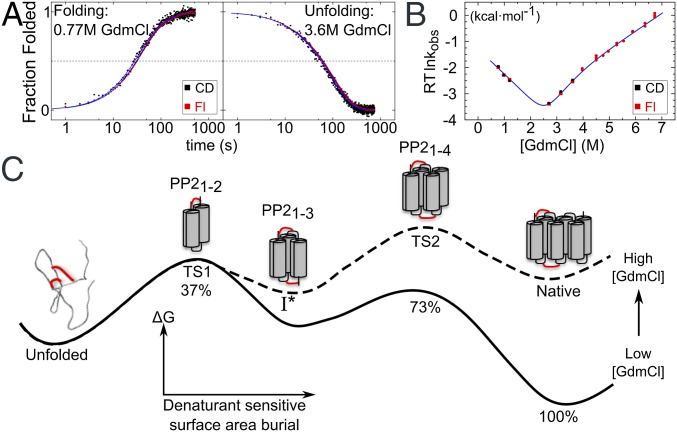

Fig. 4.

Folding kinetics of sfAFP. (A) Folding of sfAFPR62W was monitored using CD (black) and Trp fluorescence (red) and fit using a double-exponential model (blue lines). The final GdmCl concentration is noted in each panel. (B) Chevron plot fit using a two-state model with two TSs and a high-energy intermediate I*. (C) Proposed folding pathway and free-energy surface at low (solid line) and high (dashed line) denaturant concentration where TS1 and TS2 are rate limiting, respectively. The shift in the rate-limiting barrier results in a kink in the chevron plot, which can be explained by the presence of a high-energy I* state. TS1 and TS2 bury 37% and 73% of the denaturant-sensitive surface area, respectively. Only the folded portions of the TS1, I*, and TS2 are shown for simplicity. Red lines indicate disulfide bonds.

Fig. S2.

Folding and unfolding data for R62W sfAFP at different GdmCl concentrations at 4 °C. (A) Refolding and unfolding traces are monitored using CD (black) and Trp fluorescence (blue). (B) Residuals of the fits to single (black) and double (red) exponentials are shown for both CD and fluorescence data. (C) Major (black) and minor rates (red) obtained using double-exponential fits to the kinetic data. (D) The relative amplitudes of the major and minor phases from C are shown in black and red, respectively.

The CD and fluorescence traces were fit to a single-exponential function having nearly identical rates (Fig. S2 and Table S2). This agreement indicates that the two signals are tracking processes that are limited by the same kinetic barrier and that folding occurs in a two-state manner without the accumulation of intermediates. The fit to the data improved slightly when allowing for a second phase for both probes of up to 10 or 20% of the total signal for unfolding or folding, respectively (Fig. S2 and Table S3). A second phase observed by CD and fluorescence, both in rate and amplitude, suggests heterogeneity in the starting state rather than the accumulation of an intermediate. The slow minor folding phase could be due to cis–trans Pro isomerization occurring during the minute-long refolding process, whereas the fast minor unfolding phase may be due to a nonnative proline isomer in an otherwise-folded structure.

Table S2.

Single-exponential fit parameters for manual mixing (<4 GdmCl)

| Reaction | [GdmCl], M | τCD, s | τFl, s | τCD/τFl |

| Folding | 0.77 | 43.4 ± 0.6 | 48.4 ± 0.3 | 0.90 ± 0.01 |

| 0.98 | 76.6 ± 1.0 | 77.0 ± 0.3 | 1.00 ± 0.01 | |

| 1.20 | 122 ± 2 | 113 ± 0 | 1.07 ± 0.01 | |

| Unfolding | 2.7 | 421 ± 2 | 474 ± 1 | 0.89 ± 0.01 |

| 3.15 | 192 ± 1 | 229 ± 0 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | |

| 3.6 | 87.1 ± 0.7 | 97.0 ± 0.2 | 0.90 ± 0.01 |

Table S3.

Double-exponential fit parameters for manual mixing (<4 GdmCl)

| Reaction | [GdmCl], M | τCD, s* | (A1/Σ|A|)CD† | τFl, s* | (A1/Σ|A|)Fl† | τCD/τFl* |

| Folding | 0.77 | 34.6 ± 1.6 | 0.86 ± 0.03 | 37.2 + 0.4 | 0.83 ± 0.01 | 0.93 ± 0.04 |

| 160 ± 48 | 144 ± 7 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | ||||

| 0.98 | 63.0 ± 6.2 | 0.83 ± 0.07 | 64.2 + 0.8 | 0.84 ± 0.01 | 0.98 ± 0.10 | |

| 257 ± 235 | 229 ± 25 | 1.1 ± 1.0 | ||||

| 1.20 | 95.2 ± 11.1 | 0.78 ± 0.12 | 87.0 ± 2.0 | 0.69 ± 0.03 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | |

| 256 ± 99 | 180 ± 8 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | ||||

| Unfolding | 2.7 | 448 ± 5 | 0.91 ± 0.01 | 474 ± 1 | 0.96 ± 0.02 | 0.94 ± 0.01 |

| 54.6 ± 9.4 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 32 ± 17 | ||||

| 3.15 | 200 ± 2 | 0.92 ± 0.01 | 230 ± 0 | 0.96 ± 0.00 | 0.87 ± 0.01 | |

| 21.1 ± 5.8 | 4.9 ± 0.6 | 4.3 ± 1.3 | ||||

| 3.6 | 89.6 ± 1.2 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 100 ± 0 | 0.91 ± 0.00 | 0.89 ± 0.01 | |

| 10.3 ± 4.9 | 11.0 ± 0.4 | 0.94 ± 0.45 |

Major and minor phases are shown in top and bottom rows, respectively.

A1 is the major amplitude and is divided through by the sum of the amplitude magnitudes—only in a few cases does the second phase has the opposite sign in amplitude.

Below 4.5 M GdmCl, the major folding and unfolding phases could be fit with a two-state U↔N model, with the activation free energies for folding and unfolding being linear with denaturant concentration (19). However, the unfolding region of the associated chevron plot exhibits a change in slope at ∼4.5 M GdmCl (Fig. 4B). Such kinks have been observed in the unfolding of other apparent two-state proteins, and analyzed using a reaction scheme (Fig. 4C) with two sequential transition states, TS1 and TS2, and an intervening high-energy intermediate state (I*) of indeterminable stability (20, 21). Below 4.5 M GdmCl, TS1 is rate-limiting for folding and unfolding. The kink arises from the differential surface burial (denaturant dependence) of TS1 and TS2 (Table S4), which results in TS2 becoming rate limiting for unfolding above 4.5 M GdmCl. Although postulating an I* species complicates the energy surface, the state does not accumulate, and, therefore, folding still appears kinetically two-state.

Table S4.

Kinetics and thermodynamics of sfAFP folding using different kinetic models

| Kinetic model | k (0 M),s−1 | m,kcal·mol−1·M−1 | βT | ΔG0 (0 M), kcal·mol−1 |

| Two-state, fit from 0 to 4.5 M GdmCl | ||||

| U→N | 0.15 ± 0.03 | 1.23 ± 0.09 | 0.53 ± 0.02 | |

| N→U | (9.3 ± 1.3) × 10−6 | 1.07 ± 0.02 | ||

| U↔N | 2.30 ± 0.07 | 5.33 ± 0.10 | ||

| Three-state model with high-energy intermediate | ||||

| U→I* | (9.6 ± 2.7) × 10−2 | 0.95 ± 0.11 | 0.37 ± 0.06 | |

| TS1↔TS2 | 0.90 ± 0.19 | 3.06 ± 0.44 | ||

| N→I* | (2.2 ± 1.1) × 10−4 | 0.68 ± 0.05 | 0.27 ± 0.01 | |

| U↔N | 2.53 ± 0.16 | 6.43 ± 0.58 |

This kinetic analysis produced a value for the equilibrium stability of sfAFPR62W, ΔGeq = 6.4 ± 0.6 kcal·mol−1. Because the folding rates were obtained using a double-jump protocol that maintained the native Pro isomers, the chevron-derived stability reflects the difference between the native state and a denatured state having the native isomers. The chevron analysis also produced an equilibrium m value, mo = 2.5 ± 0.2 kcal·mol−1·M−1, consistent with other proteins. The mo value is a measure of the surface buried going from the unfolded to the native state (22). sfAFP is predicted to have an mo = 1.8 kcal·mol−1·M−1 (23), assuming an unstructured denatured state model (13), which is less than our experimental value. If a rapidly formed intermediate did exist and had escaped our detection, the net mo would be reduced. Hence, the sizable mo value obtained from the chevron provides further support that folding is dominated by two energy wells.

SAXS Studies.

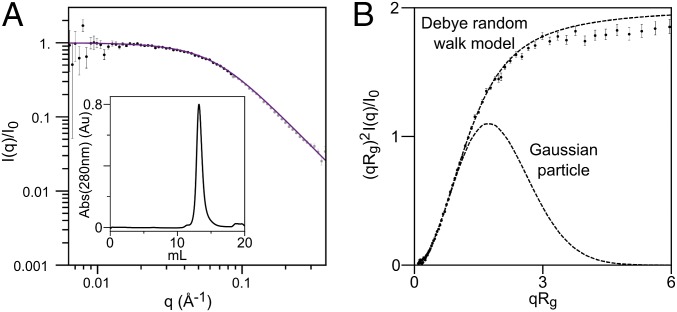

Poly(Gly) sequences have been observed to form collapsed or aggregated structures (24–28), and so we sought to determine whether a denatured state of sfAFP with 46% Gly content would behave similarly. To this end, we measured the properties of sfAFPH32W with reduced disulfide bonds using SAXS coupled with inline size exclusion chromatography (SEC) (Fig. 5). Without the two disulfide bonds, the species is not the true unfolded state of sfAFP. However, the reduced species provides an analog accessible under aqueous conditions to ascertain whether sfAFP’s Gly content is sufficient to promote collapse or aggregation. The reduced protein eluted from the size exclusion column as a single peak at an elution volume earlier than expected for a globular (i.e., collapsed) protein. Furthermore, the scattering profile was consistent with the Debye model for a random walk (29), indicating that the reduced analog was unfolded with at least one broken disulfide bond (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

SAXS on reduced and unfolded sfAFP. (A) Data are fit to a Debye random walk model out to qRg ≤ 2 (black versus gray data points). (Inset) SEC elution profile. (B) Data, presented in the form of a dimensionless Kratky plot, are compared with that for a random walk and a Gaussian particle. The protein in 10 mM DTT was injected onto a SEC column equilibrated with 2 mM DTT, pH 7.4.

The fit of the data with the Debye model over the range q·Rg ≤ 2 yields a radius of gyration, Rg = 23.1 ± 0.2 Å. The crystal structure Rg is 13.3 Å, whereas the expected Rg for a chemically denatured protein of this size is 25.4 Å. The latter is calculated from the known correlation between chain length (N = 81) and Rg for a self-avoiding random walk (SARW), Rg = 2N0.59 (30), when corrected by 5% for the difference between the scaling for an Ala- versus Gly-containing random walk (31). Although this disordered state (under aqueous conditions) is not as expanded as a completely self-avoiding random walk, the SAXS data indicates that the reduced analog is not collapsed, consistent with findings on other unfolded proteins (32–35). These results indicate that high glycine content does not necessarily produce a collapsed globule or aggregation, unlike that observed both experimentally and in simulations using poly(Gly) sequences (24–28). Possibly the difference lies in the Cβ-containing residues in the heterogeneous sfAFP sequence that serve to restrict an otherwise-favorable collapse of a polypeptide with a high Gly content.

Conformational Entropy.

Explicit solvent molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were analyzed to calculate the conformational entropy of sfAFP in its native state for comparison with the model protein ubiquitin (Ub). Entropy is calculated according to S = -R Σi PilnPi, where Pi is the population in 10° × 10° pixels in the Ramachandran map (36, 37). We find that residues in sfAFP’s PP2 helices and in Ub’s β-sheets exhibit comparable backbone entropy (Fig. 2B). Helical residues in Ub have tighter (ϕ,ψ) distributions and, hence, significantly lower entropies (Fig. 2C). In entropic terms, the less restricted motions in PP2 helices translates to an entropic benefit of ΔS = 0.5 kcal·mol−1·res−1/(300 K), compared with helical residues.

Our prior studies (36, 37) found that the backbone entropy of glycine in the unfolded state exceeds other residues by 0.3 kcal·mol−1·res−1/(300 K). However, other residue types additionally lose side-chain entropy upon folding. For Ub, the average loss of side-chain entropy for the non-Gly, -Ala, and -Pro residues is ΔS = 0.3 kcal·mol−1·res−1/(300 K). This extra entropy loss of side-chain entropy produces an average net entropy loss upon folding similar to that of glycine. Also, the two disulfide bonds in sfAFP (C1–C28, C13–C43) reduce the conformational entropy of the unfolded state through covalent loop closure, by ∼5 kcal·mol−1·(300 K)−1 (although possibly less as the loops are intertwined) (38).

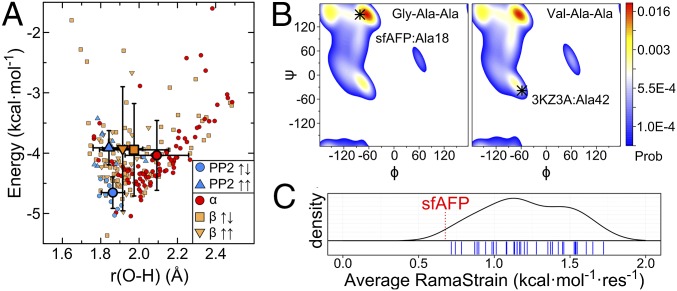

H-Bonds.

sfAFP has an H-bond content and amide burial level that is typical of similar-sized proteins (Fig. 2A). However, sfAFP’s H-bonds are on average 0.17 and 0.09 Å shorter than α-helical and β-sheet H-bonds, respectively (Fig. 6A). The reduced distances suggest that the lack of side chains in the core of sfAFP allows the H-bonds to energy minimize and dictate the inter-PP2 helix separation distance. Consistently, the shortest H-bonds in sfAFP are in the middle of the helices, and longer H-bonds are located near the turns where additional constraints are present. We suspect that side-chain packing and the requirement that the main chain twist result in slightly longer H-bonds in β-sheets and α-helices compared with those in the core of sfAFP.

Fig. 6.

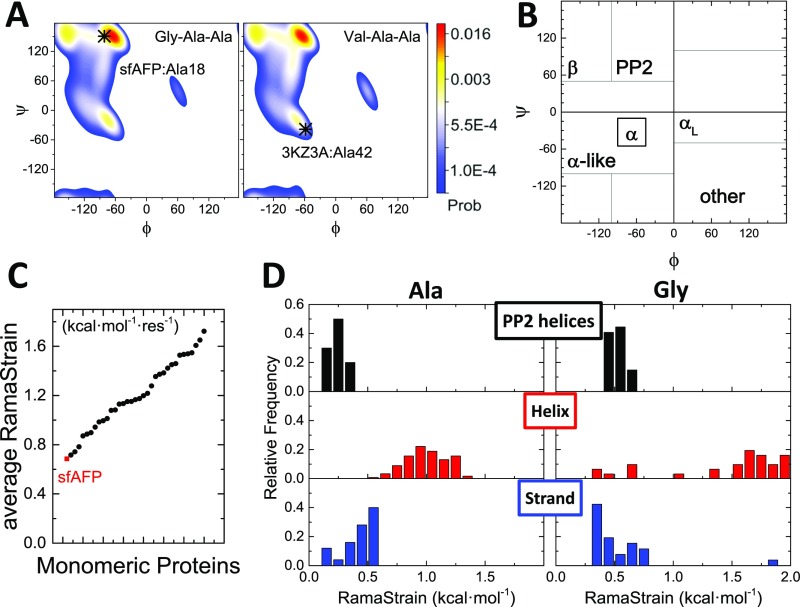

Proposed major factors that stabilize sfAFP. (A) Calculated H-bond energies and distances using DFT for ε = 4 in sfAFP and similar-sized proteins are sorted according to secondary structure. For clarity, two points at (1.60 Å, 0.51 kcal·mol−1) and (1.65 Å, 0.65 kcal·mol−1) lying outside the plotted area are not shown. Larger symbols with error bars denote average values and SDs. (B) Ramachandran probability distributions for Ala18 and Ala42 in the unfolded states of sfAFP and λ-repressor, respectively, based on a coil library (59). The native-state conformations are indicated. RamaStrain is the work required to shift the (ϕ,ψ) distribution of the unfolded state to that of the native state. More work is required to adopt a helical conformation compared with a PPII conformation. (C) A kernal-density estimate of average RamaStrain calculated for a set of 35 similar sized proteins (individual values denoted with blue tick marks). sfAFP’s average RamaStrain is shown with a red dashed line.

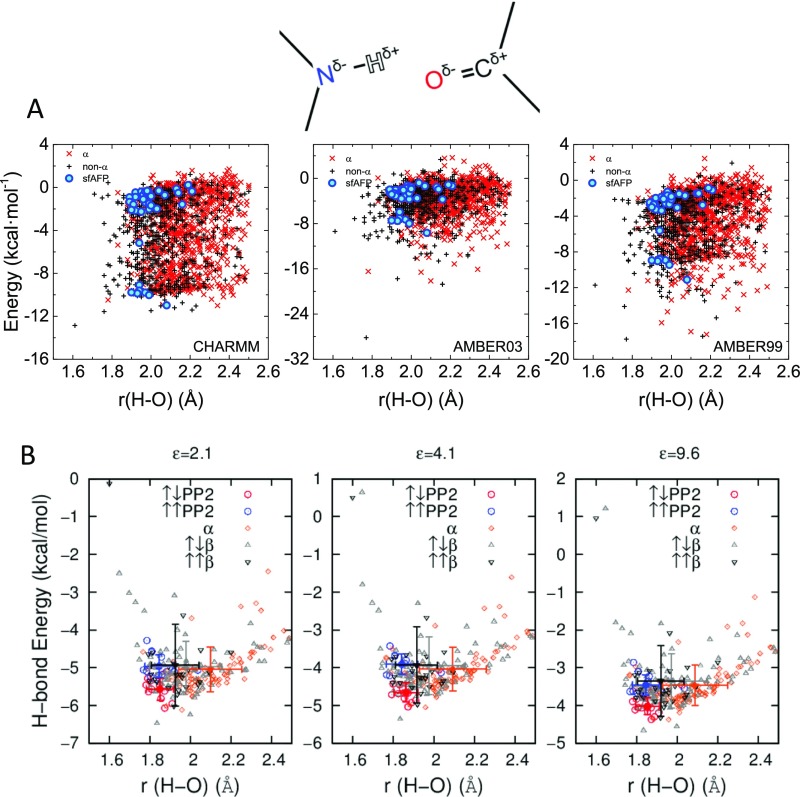

Translation of the difference in H-bond length into energetic terms is challenging. As a proxy, electrostatic energy calculations between the amide and carbonyl partial charges with molecular force fields were carried out but exhibited little distance dependence (Fig. S3A). Furthermore, the H-bonds in sfAFP appear energetically indistinguishable from the other H-bonds according to this simple analysis based on electrostatics.

Fig. S3.

Estimates of H-bond energy. (A) Energies are calculated using partial charges from three different force fields for residues in the sfAFP (2pneA) (blue), helical (red), and nonhelical residues (green) in similarly sized proteins. (B) Calculated H-bond energies and distances using B3LYP DFT on hydrogen-bond geometries in sfAFP and 34 other proteins sorted according to secondary structure. Energy calculations are carried out with varying dielectric constants. Cross-lines indicate average values for each secondary structure type.

As an alternative, quantum-mechanical (QM) calculations using B3LYP density functional theory (DFT) (39) were performed on 29 pairs of N-methylacetamide (NMA) molecules having geometries matching the 14 parallel and 15 antiparallel PP2 helical H-bond orientations found in sfAFP. An additional 215 NMA pairs using geometries found in our protein test set (100 α-helical, 100 antiparallel, and 15 parallel β orientations) were included for comparison (Fig. 6A, Fig. S3B, and Table S5). The H-bond energy was defined as the difference between the NMA pair energy and the sum of the individual energies in the same configuration, EHB = Etotal − (E1 + E2). Three solvent dielectric constants were examined, ε = 2, 4, and 10, which likely covers the value inside a protein (40). On average, the antiparallel PP2 H-bond is ∼0.3–0.7 kcal·mol−1 more stable than those in other secondary structures. The most stable H-bonds tended to have an H–O distance of 1.85–1.90 Å. Increasing ε from 2 to 4 or 10 stabilizes H-bonds by about 0.8 or 1.3 kcal·mol−1·HB−1, respectively, but has little impact on the ΔEHB between the different secondary structures (Fig. S3B).

Table S5.

Hydrogen bond interaction energies in sfAFP

| Inter-PP2-orientation | Res(NH) | Res(CO) | r (H–O), Å | θ (NHO), ° | EHB(ε = 2.1), kcal·mol−1 | EHB(ε = 4.1), kcal·mol−1 | EHB(ε = 9.6), kcal·mol−1 |

| Parallel | 3 | 29 | 1.86 | 164.7 | NC | −3.803 | −3.228 |

| 6 | 32 | 1.81 | 163.3 | −4.561 | −3.672 | −3.103 | |

| 9 | 35 | 1.78 | 163.2 | −5.097 | −4.214 | −3.627 | |

| 15 | 44 | 2.04 | 145.7 | −5.063 | −4.133 | −3.548 | |

| 18 | 47 | 1.88 | 155.5 | −5.105 | −4.178 | −3.577 | |

| 21 | 50 | 1.81 | 159.6 | −4.587 | −3.694 | −3.106 | |

| 24 | 53 | 1.83 | 174.7 | −5.308 | NC | −3.721 | |

| 33 | 62 | 1.80 | 165.7 | −5.242 | NC | −3.666 | |

| 36 | 65 | 1.78 | 155.3 | −4.280 | −3.424 | −2.861 | |

| 39 | 68 | 1.77 | 173.0 | −5.059 | −4.190 | −3.634 | |

| 45 | 71 | 1.92 | 169.6 | −5.093 | NC | −3.634 | |

| 48 | 74 | 1.84 | 168.1 | −5.207 | NC | −3.744 | |

| 51 | 77 | 1.86 | 164.4 | −4.716 | −3.887 | −3.352 | |

| 54 | 80 | 1.86 | 169.7 | −5.180 | NC | −3.591 | |

| Antiparallel | 16 | 10 | 2.02 | 158.7 | −5.004 | −4.061 | −3.464 |

| 19 | 7 | 1.85 | 178.5 | −5.817 | −4.806 | −4.158 | |

| 22 | 4 | 1.91 | 167.2 | −5.954 | −4.866 | −4.192 | |

| 31 | 22 | 1.83 | 160.0 | NC | −4.452 | −3.798 | |

| 34 | 19 | 1.85 | 173.4 | NC | −4.670 | −4.053 | |

| 37 | 16 | 1.83 | 177.1 | NC | −4.687 | −4.062 | |

| 46 | 37 | 1.87 | 176.5 | −5.619 | −4.668 | −4.063 | |

| 49 | 34 | 1.79 | 168.7 | −5.634 | −4.710 | −4.114 | |

| 52 | 31 | 1.80 | 177.5 | −5.359 | −4.428 | −3.830 | |

| 61 | 52 | 1.87 | 172.4 | −6.070 | −5.032 | −4.369 | |

| 64 | 49 | 1.81 | 170.7 | −5.568 | NC | −4.055 | |

| 67 | 46 | 1.78 | 177.2 | −5.461 | NC | −3.895 | |

| 73 | 67 | 1.89 | 154.7 | NC | −4.930 | −4.300 | |

| 76 | 64 | 1.85 | 157.7 | −5.445 | −4.538 | −3.951 | |

| 79 | 61 | 1.79 | 163.0 | −5.284 | NC | NC |

Calculated from NMA dimer interaction energies using the density functional theory B3LYP/6-311g(d,p) method. EHB = E12 − (E1 + E2), that is, the difference between the dimer energy and the sum of the monomer energies. Energies are calculated using various dielectric constants. NC, not converged.

In addition to amide H-bonds, sfAFP has 15 CH–O=C H-bonds, which are also found in other PP2-containing proteins and polypeptides (41, 42). Although the strength of these interactions is unknown, they are likely to be weak (41, 43), especially considering that in sfAFP the carbonyl oxygen already is involved in a backbone H-bond.

Another possible stabilizing factor is the n→π* interaction between adjacent peptide bonds (44). Simulations have suggested that dipole–dipole interactions between peptide bonds, which correspond to the quantum mechanical n→π* interactions, can explain the self-association of polyglycine peptides (25, 45). The distance between oxygen and carbons is shorter in α than PP2 helices (2.9 and 3.2 Å, respectively), suggesting that n→π* interactions are less significant in sfAFP than in typical helical proteins. Because the stability of helical proteins already can be attributed to hydrophobic burial, we infer that n→π* interactions are unlikely to provide significant stabilization for sfAFP.

Significance.

Despite lacking canonical secondary structures or a hydrophobic core, sfAFP both folds cooperatively and is stable. These two properties are related but distinct (2, 46); for example, a small subpopulation can fold cooperatively to a unique structure even under strongly destabilizing conditions if there are two distinct thermodynamic wells. We first discuss sfAFP’s stability.

In 1951, Pauling and others (2, 47, 48) stressed the importance of H-bonds. The overall benefit of H-bonding to stability, however, is unclear as the net number of total protein plus water H-bonds typically remains nearly constant upon folding. In 1959, Kauzmann (49) stressed that the hydrophobic effect is the dominant factor in protein stability, in agreement with more recent thinking (50, 51).

Hydrophobic burial provides a large entropic benefit, ΔSsolvent, due to the release of water molecules caging the hydrophobic groups in the unfolded state (50, 52). The experimentally observed entropy loss upon folding often is near zero: ΔSexp ∼ 0 ∼ ΔSsolvent + ΔSconf, implying that the gain in solvent entropy gain is largely counterbalanced by the loss of conformational entropy, ΔSsolvent ∼ −ΔSconf (50, 52). Indeed, our estimation of ΔSconf ∼ 1.4 kcal·mol−1·res−1/(300 K) (36, 37), is similar to the above estimate of hydrophobic stabilization. However, sfAFP buries only 40% of the hydrophobic surface area of a typical protein. This difference equates to a reduction in stability of ∼1 or 1.4 kcal·mol−1·res−1 (9, 10). Because sfAFP lacks extensive hydrophobic burial, we expect a reduction in ΔSsolvent but no corresponding change in ΔSconf. Hence, the compensating factors that help stabilize sfAFP are expected to have a significant entropic component.

We propose that three factors largely compensate for the lack of hydrophobic burial in sfAFP: strong H-bonds between PP2 helices, heightened native state entropy, and similarity between the residue-level statistical bias toward PP2 dihedral angles in the unfolded state and the actual PP2 structure in the native state. According to our DFT calculations, sfAFP’s 15 antiparallel PP2 H-bonds are stronger by ∼0.5 kcal·mol−1·H-bond−1 compared with other types of H-bonds (Fig. 6A). sfAFP’s heightened native-state entropy stabilizes the protein by reducing the loss of entropy upon folding, also achievable through the use of specific amino acids (53). Compared with α-helices, the backbone of residues in sfAFP’s PP2 helices are slightly more flexible and sample more area in the Ramachandran map during MD simulations (Fig. 2C), which equates to an increased native state entropy worth ΔS ∼ 0.5 kcal·mol−1·res−1·(300 K)−1.

The third major proposed factor in sfAFP’s stability is the similarity between the backbone conformations in the folded and unfolded states. The CD spectrum of the denatured chain (Fig. 3A) indicates that the backbone preferentially adopts (ϕ,ψ) values compatible with PP2 geometry (13, 14, 16, 54–56). The unfolded state’s PP2 bias is a statistical property and does not necessitate that the chain have contiguous stretches of PP2 conformers, as observed in the native PP2 helices. Rather, the backbone samples a variety of (ϕ,ψ) angles, and according to the SAXS data, behaves nearly as a SARW when the disulfide bonds are broken.

The PP2 bias is especially strong for chains containing alanine (57) and glycine (24), which are found at high levels in sfAFP’s PP2 helices (11 Ala, 33 Gly, out of 68 helical residues). We propose that the strong residue-level bias toward PP2 conformations in the unfolded state reduces the free energy needed to shift its backbone distribution to the native-state distribution. We term this energy “RamaStrain.” It has both entropic and enthalpic components. It would be solely entropic if the probability distribution is such that all allowed angles are equally probable (an energy surface with flat-bottom wells). Similar principles have been used to reduce the entropy in the unfolded state through the use of selected substitutions (58).

We evaluated RamaStrain using linkage and an unfolded state (ϕ,ψ) distribution obtained from a structure-based coil library (59), ΔGRamaStrain = −RT ln Punf(ϕ,ψ)nat, where Punf(ϕ,ψ)nat is the probability of a residue in the unfolded state occupying the native (ϕ,ψ) basin (Fig. 6, Fig. S4, and SI Methods). Compared with a test set of 35 comparably sized proteins, sfAFP’s RamaStrain is smaller by 0.53 ± 0.28 kcal·mol−1·res−1. This serves as a third factor compensating for sfAFP’s lack of hydrophobic burial.

Fig. S4.

RamaStrain. (A) Ramachandran probability landscapes for Ala18 and Ala42 in the unfolded states of sfAFP and λ-repressor, respectively, based on a coil library (59). (B) Ramachandran basin boundaries used in the RamaStrain calculation. (C) RamaStrain was evaluated for a set of 34 proteins of comparable size to sfAFP. The average RamaStrain in sfAFP is lower than for similarly sized proteins. (D) Distributions of RamaStrain for Ala and Gly residues in sfAFP and the test set, organized by secondary structure. A bias against helices (and, to a lesser extent, strands) in the unfolded state is apparent.

Cooperativity.

No generally accepted answer exists to the origin of the all-or-none cooperativity typically observed in the folding of globular proteins. Although hydrophobic burial alone may be insufficient to yield cooperative folding behavior (60, 61), a common presumption is that formation of a hydrophobic core is requisite for two-state folding behavior (11). Simulations and experiments have also stressed the importance of long-range contacts (62, 63). Other factors include multibody energy terms (64), instability of isolated substructures, side-chain packing (11), desolvation (65), and the lack of stable, misfolded structures.

Thermal denaturation of sfAFP produces a sharp unfolding transition with concurrent changes in local (fluorescence) and global (CD) probes, consistent with the native and unfolded states being the only significantly populated species. Similarly, the two probes track each other during the kinetic measurements. Both unfolding and refolding reactions are primarily monophasic, with rate constants that vary linearly with denaturant concentration. The effect of proline isomerization compromises our ability to apply further tests of cooperativity [e.g., comparison of ΔHvan’t Hoff and ΔHcalor (66)]. However, the available data provide strong preliminary evidence that sfAFP folds in a single kinetic step, potentially through a high-energy intermediate. Taken together, our findings suggest that a hydrophobic core with specific side-chain packing is not an absolute requirement for cooperative folding behavior.

In sfAFP, the two central helices, PP23 and PP24, collectively form H-bonds with all other PP2 helices, with each one individually contacting four helices (Fig. 1D). This level of contact between secondary structures is similar to that found for β-strand and α-helices in similar-sized proteins. The extensive interaction network found in sfAFP is reflected in a residue–residue contact map with many off-diagonal elements and a high relative contact order value of 0.17 (Ub’s value is 0.15) (67). These structural intricacies mimic those observed in globular proteins and likely contribute to sfAFP’s two-state folding behavior.

We hypothesize the following folding pathway to rationalize the presence of a large free-energy barrier between the native and unfolded states (Fig. 4C). The presence of the two disulfide bonds biases folding to initiate at the N terminus. However, the formation of a single PP2 helix or even a pair of helices with only a single helix–helix interface is likely to be unstable. The βTanford surface burial percentages for TS1 and TS2 are 37 ± 6% and 73 ± 1%, respectively, which suggests that two PP2 helices form in TS1, three helices in the high-energy intermediate I*, and four helices in TS2. The initial unfolding event could be the unfolding of PP26 as removing this helix is the least disruptive. However, the accompanying gain in entropy for the unfolding of a single PP2 helix comes at the expense of two helix–helix interfaces, making this event net unfavorable. Due to the uphill nature of folding the first two to three helices in TS1 and I*, and the downhill folding of the last two helices from TS2, there is a sizable free-energy barrier on an energy surface dominated by two wells. Further studies are required to evaluate this proposed pathway.

The well-defined native state of sfAFP is a product of its H-bonding pattern, side-chain packing requirements, and turn sequences. The native arrangement of the PP2 helices uniquely positions all Cβ atoms outward from the core to promote formation of the extensive H-bond network. In addition, the five turns have specific sequence motifs. Four turns contain a Pro, of which two adopt the noncanonical cis ω angle. The remaining turn sequence, GGTG, contains two Glys (G56, G58) with (ϕ,ψ) dihedral angles that are strongly disfavored for all other residues. The location of the turns in the sequence also produces nearly equal length PP2 helices and hence maximizes the number of interstrand H-bonds. In sum, the requirement of having Gly at critical positions combined with the strong turn signals helps produce a well-defined native state for sfAFP.

SI Methods

Experimental Measurements.

All experiments were carried out using 10 mM phosphate, pH 8.0, at 4 °C. Equilibrium denaturation and manual mixing kinetics were monitored with a Jasco J-715 CD spectrometer. CD was monitored at 219 nm with a 10 nm bandwidth, and fluorescence (λexcite = 285 nm) was measured orthogonally using a 310-nm cutoff filter. For manual mixing kinetics, CD and fluorescence were simultaneously monitored at 226 nm with a 5-nm bandwidth. Temperature ramp rates of 0.25, 1, and 4 °C·min−1 were used during thermal denaturation.

For double-jump folding experiments, 1.5 mM protein (in 10 mM phosphate, pH 8.0) was first diluted 10-fold into 6.6 M GdmCl, and after 10 s, the solution was diluted 10-fold into a 1-cm path length cuvette containing 0–0.5 M GdmCl. The final [GdmCl] concentrations were 0.8, 1.0, and 1.2 M. For [GdmCl] > 4 M, kinetic data were collected at a final protein concentration of 7–50 μM using a BioLogic SFM-4000 stopped-flow apparatus connected to a PTI A101 arc lamp.

ΔCp was calculated from Guinn et al. (23). Briefly, the model assumes that ΔCp can be decomposed as a linear function of the change in hydrocarbon and amide surface burial during folding, that is,

where the coefficients εH and εA are taken from hydrocarbon and amide transfer studies, respectively. From table 1 of ref. 23, εH = 0.34 ± 0.02 cal·mol−1·K−1·Å−2 and εH = −0.14 ± 0.04 cal·mol−1·K−1·Å−2. Solvent-accessible calculations are carried out on the native PDB structure (2PNE) and a denatured state ensemble generated using coarse-grained molecular dynamics with statistical potentials based on Ramachandran frequencies of turn–coil–bridge residues (59).

SAXS Measurements of Reduced sfAFPH32W.

The two disulfide bonds were reduced by equilibrating in 10 mM DTT to enable unfolding the protein at room temperature. SAXS measurements were taken at the BioCAT facility at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. The protein was injected onto a Sephadex G75 size-exclusion column equilibrated with 2 mM DTT, 20 mM Hepes, 150 mM KCl, pH 7.4, and directly connected to the observation capillary.

MD Simulations.

sfAFP [PDB ID code 2PNE (3)] was solvated in a water box with the TIP3P water model (68) with intact disulfide bonds. Simulations were performed using the program NAMD (69) with the CHARMM36 forcefield (70). Following energy minimization, the system is gradually heated from 240 to 300 K while holding backbone atoms restrained with a harmonic potential. Upon reaching 300 K, the restraint spring constants are progressively decreased to zero over 1.3 ns. Following another 7.7 ns of equilibration with a 1-fs time step, a long time trajectory is calculated using a 2-fs time step, and structures are saved every 10 ps.

Entropy Calculations.

Backbone entropy calculations were followed using the same method as in refs. 36 and 37 by first generating the probability distributions of each residue’s (ϕ,ψ) pair, P(ϕ,ψ). The entropy is then , where the sum is over the discretized Ramachandran space. Joint entropies between neighboring residues are calculated in like-manner using four-dimensional probability distributions, that is, . The effect of neighboring residues on the backbone entropy of a residue is ΔSi = Si,i+1 – (Si + Si+1), where Si,i+1 is the joint entropy over residues i and i + 1. The final corrected entropy for residue i incorporates effects from both residues i ± 1, that is, Si,corr = Si + 1/2(ΔSi,i+1 + ΔSi-1,i).

Hydrogen-Bond Electrostatic Energy Calculations.

Hydrogen bonds are determined in sfAFP using a threshold cutoff of dist(H–O) ≤ 2.5 Å, and angle(N–H–O) ≥ 120°. Electrostatic energies within the hydrogen bond are calculated between the partial charges on H+0.31e, N−0.47e, O−0.51e, and C+0.51e using the CHARMM parameters (71) (similar results were found with Amber) (Fig. S3A).

Quantum H-Bond Calculations.

The H-bond energetics were calculated using the Beck, 3-parameter, Lee–Yang–Parr (B3LYP) density functional method with the 6–311+g(d,p) basis set and the Gaussian 09 program (39), by evaluating the interaction energy of the NMA dimer. The influence of local electrostatic environment was probed with a polarizable continuum solvent model (PCM) (72). Positions of all hydrogen atoms and methyl carbon atoms of the NMA dimer were optimized in the QM calculations, with coordinates of the amide nitrogen atoms and the carbonyl groups kept identical to that in the crystal structures.

RamaStrain Calculations.

Using thermodynamic linkage, we define the RamaStrain of a residue according to the following set of equilibria:

where

where is the probability of a residue in the unfolded state residing in the native (ϕ,ψ) basin, of the six possibilities (14): β, authentic α-helix, α-helix-like, PP2, left-handed helix, and other (Fig. S4B). The complete folding equilibrium is given by the following:

where [Unfolded] = [Unfoldednative basin] + [Unfoldednonnative basin]. We calculate RamaStrain according to the following:

Calculations of the unfolded (ϕ,ψ) distribution were conducted accounting for the nearest neighbor dependence. In lieu of having such distributions for amino acid triplets, we combined probability maps for amino acid pairs taken from a coil library (59). The (ϕ,ψ) probability map for amino acid a1 in the triplet a0-a1-a2 is calculated as follows:

Selecting Similarly Sized Proteins for Comparison.

A set of proteins similarly sized to sfAFP are culled from the ASTRAL-SCOPe database (73) by selecting for protein domains having 76–86 aa with less than 25% sequence homology. The protein domains are allowed to be α, β, α + β, and α/β, but not involved in protein–protein interactions. The 32 remaining proteins are d1a62a2, d1af7a1, d1aopa2, d1bdoa, d1cvra1, d1dp7p, d1ei5a1, d1h4ax1, d1iqza, d1k0ma2, d1kp6a, d1l3ka1, d1lbua1, d1m1ha1, d1sqwa1, d1t95a2, d1tifa, d1tuaa1, d1u84a, d1vcca, d1x6oa2, d1yt3a2, d2bkfa1, d2fq3a1, d2gaua1, d2hkja1, d2nsfa2, d2o4aa, d3l2ca, d4eiea, d4j7da, and d4klia1. Ubiquitin (1UBQ) and lambda repressor 6–85 (3KZ3A) are included in the dataset as well.

Conclusion

Despite lacking α and β structures and a hydrophobic core, the folding behavior of sfAFP matches those of proteins that have such features. Hence, they are unnecessary for folding cooperativity and stability. sfAFP’s two-state behavior can be rationalized by its long range contacts and unique structure due to specific H-bonding requirements and turn motifs. What is less clear are the stabilizing terms that compensate for sfAFP’s reduced amount of hydrophobic burial, estimated to provide 1 or 1.4 kcal·mol−1·res−1 less stability compared with typical proteins. We propose a major compensation for the lack of burial is that the intrinsic residue-level PP2 bias in the unfolded state reduces the free-energy cost of the backbone adopting the native PP2 geometry by ∼0.5–1 kcal·mol−1·res−1 compared with other, especially helical proteins. In addition, DFT calculations indicate that sfAFP’s antiparallel H-bonds are more stable by ∼0.5 kcal·mol−1·H-bond−1 compared with those in other secondary structures. Further studies are required to generate a more complete description of the energetics and folding behavior of this fascinating protein.

Methods

All variants of sfAFP were prepared as previously described (12). All experiments were carried out using 10 mM phosphate, pH 8.0, at 4 °C unless otherwise noted. Equilibrium denaturation and manual mixing kinetics were monitored with a Jasco J-715 CD spectrometer. For [GdmCl] > 4 M, kinetic data were collected using a BioLogic SFM-4000 stopped-flow apparatus connected to a PTI A101 arc lamp. SAXS measurements were taken at the Biophysics Collaborative Access Team (BioCAT) facility at the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory. Further descriptions of the methods are listed in SI Methods.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Raines, G. Rose, and members of our groups for useful comments; E. Haddadian for the MD trajectory; S. Chakravarthy and A. Zmyslowski for assistance with collecting SAXS data; and J. Jumper for assistance with the RamaStrain calculations. Computations were performed on the Midway cluster at The University of Chicago. This work was supported by NIH Research Grants R01 GM055694 (to T.R.S.) and GM-072558 (to B.R.), and by National Science Foundation Grant CHE-1363012. Use of BioCAT beamline was supported by the Advanced Photon Source, a US Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357, and BioCAT NIH Grants 9 P41 GM103622 and 1S10OD018090-01. W.Y. was supported in part by National Creative Research Initiatives (Center for Proteome Biophysics) of National Research Foundation, Korea (Grant 2011-0000041). This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (to Z.P.G.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1609579114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pastore A, Wei G. Editorial overview: Folding and binding: Old concepts, new ideas, novel insights. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2015;30:iv–vi. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rose GD, Fleming PJ, Banavar JR, Maritan A. A backbone-based theory of protein folding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(45):16623–16633. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606843103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pentelute BL, et al. X-ray structure of snow flea antifreeze protein determined by racemic crystallization of synthetic protein enantiomers. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(30):9695–9701. doi: 10.1021/ja8013538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies PL. Ice-binding proteins: A remarkable diversity of structures for stopping and starting ice growth. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39(11):548–555. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Todde G, Whitman C, Hovmöller S, Laaksonen A. Induced ice melting by the snow flea antifreeze protein from molecular dynamics simulations. J Phys Chem B. 2014;118(47):13527–13534. doi: 10.1021/jp508992e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin FH, Graham LA, Campbell RL, Davies PL. Structural modeling of snow flea antifreeze protein. Biophys J. 2007;92(5):1717–1723. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.093435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Creighton T. Proteins: Structures and Molecular Properties. Freeman; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Willard L, et al. VADAR: A Web server for quantitative evaluation of protein structure quality. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(13):3316–3319. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan HS, Dill KA. Solvation: How to obtain microscopic energies from partitioning and solvation experiments. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1997;26:425–459. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.26.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharp KA, Nicholls A, Fine RF, Honig B. Reconciling the magnitude of the microscopic and macroscopic hydrophobic effects. Science. 1991;252(5002):106–109. doi: 10.1126/science.2011744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan HS, Bromberg S, Dill KA. Models of cooperativity in protein folding. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1995;348(1323):61–70. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1995.0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pentelute BL, Gates ZP, Dashnau JL, Vanderkooi JM, Kent SB. Mirror image forms of snow flea antifreeze protein prepared by total chemical synthesis have identical antifreeze activities. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(30):9702–9707. doi: 10.1021/ja801352j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jha AK, Colubri A, Freed KF, Sosnick TR. Statistical coil model of the unfolded state: Resolving the reconciliation problem. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(37):13099–13104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506078102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jha AK, et al. Helix, sheet, and polyproline II frequencies and strong nearest neighbor effects in a restricted coil library. Biochemistry. 2005;44(28):9691–9702. doi: 10.1021/bi0474822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Toal S, Schweitzer-Stenner R. Local order in the unfolded state: Conformational biases and nearest neighbor interactions. Biomolecules. 2014;4(3):725–773. doi: 10.3390/biom4030725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi Z, Chen K, Liu Z, Sosnick TR, Kallenbach NR. PII structure in the model peptides for unfolded proteins: Studies on ubiquitin fragments and several alanine-rich peptides containing QQQ, SSS, FFF, and VVV. Proteins. 2006;63(2):312–321. doi: 10.1002/prot.20788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schmid FX, Baldwin RL. Acid catalysis of the formation of the slow-folding species of RNase A: Evidence that the reaction is proline isomerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75(10):4764–4768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huyghues-Despointes BMP, Scholtz JM, Pace CN. Protein conformational stabilities can be determined from hydrogen exchange rates. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6(10):910–912. doi: 10.1038/13273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson SE, Fersht AR. Folding of chymotrypsin inhibitor 2. 1. Evidence for a two-state transition. Biochemistry. 1991;30(43):10428–10435. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sánchez IE, Kiefhaber T. Evidence for sequential barriers and obligatory intermediates in apparent two-state protein folding. J Mol Biol. 2003;325(2):367–376. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01230-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bachmann A, Kiefhaber T. Apparent two-state tendamistat folding is a sequential process along a defined route. J Mol Biol. 2001;306(2):375–386. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers JK, Pace CN, Scholtz JM. Denaturant m values and heat capacity changes: Relation to changes in accessible surface areas of protein unfolding. Protein Sci. 1995;4(10):2138–2148. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guinn EJ, Kontur WS, Tsodikov OV, Shkel I, Record MT., Jr Probing the protein-folding mechanism using denaturant and temperature effects on rate constants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(42):16784–16789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1311948110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohnishi S, Kamikubo H, Onitsuka M, Kataoka M, Shortle D. Conformational preference of polyglycine in solution to elongated structure. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128(50):16338–16344. doi: 10.1021/ja066008b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tran HT, Mao A, Pappu RV. Role of backbone-solvent interactions in determining conformational equilibria of intrinsically disordered proteins. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(23):7380–7392. doi: 10.1021/ja710446s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teufel DP, Johnson CM, Lum JK, Neuweiler H. Backbone-driven collapse in unfolded protein chains. J Mol Biol. 2011;409(2):250–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karandur D, Harris RC, Pettitt BM. Protein collapse driven against solvation free energy without H-bonds. Protein Sci. 2016;25(1):103–110. doi: 10.1002/pro.2749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holehouse AS, Garai K, Lyle N, Vitalis A, Pappu RV. Quantitative assessments of the distinct contributions of polypeptide backbone amides versus side chain groups to chain expansion via chemical denaturation. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137(8):2984–2995. doi: 10.1021/ja512062h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Debye P. Molecular-weight determination by light scattering. J Phys Colloid Chem. 1947;51(1):18–32. doi: 10.1021/j150451a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohn JE, et al. Random-coil behavior and the dimensions of chemically unfolded proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(34):12491–12496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403643101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tran HT, Wang X, Pappu RV. Reconciling observations of sequence-specific conformational propensities with the generic polymeric behavior of denatured proteins. Biochemistry. 2005;44(34):11369–11380. doi: 10.1021/bi050196l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo TY, et al. The folding transition state of protein L is extensive with nonnative interactions (and not small and polarized) J Mol Biol. 2012;420(3):220–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Konuma T, et al. Time-resolved small-angle X-ray scattering study of the folding dynamics of barnase. J Mol Biol. 2011;405(5):1284–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kathuria SV, et al. Microsecond barrier-limited chain collapse observed by time-resolved FRET and SAXS. J Mol Biol. 2014;426(9):1980–1994. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.02.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacob J, Krantz B, Dothager RS, Thiyagarajan P, Sosnick TR. Early collapse is not an obligate step in protein folding. J Mol Biol. 2004;338(2):369–382. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baxa MC, Haddadian EJ, Jumper JM, Freed KF, Sosnick TR. Loss of conformational entropy in protein folding calculated using realistic ensembles and its implications for NMR-based calculations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(43):15396–15401. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407768111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baxa MC, Haddadian EJ, Jha AK, Freed KF, Sosnick TR. Context and force field dependence of the loss of protein backbone entropy upon folding using realistic denatured and native state ensembles. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(38):15929–15936. doi: 10.1021/ja3064028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobson H, Stockmayer WH. Intramolecular reaction in polycondensations. 1. The theory of linear systems. J Chem Phys. 1950;18(12):1600–1606. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frisch MT, et al. Gaussian 09, Revision A.02. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford, CT: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilson MK, Honig BH. The dielectric constant of a folded protein. Biopolymers. 1986;25(11):2097–2119. doi: 10.1002/bip.360251106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bella J, Berman HM. Crystallographic evidence for C alpha-H...O=C hydrogen bonds in a collagen triple helix. J Mol Biol. 1996;264(4):734–742. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ramachandran GN, Sasisekharan V, Ramakrishnan C. Molecular structure of polyglycine II. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1966;112(1):168–170. doi: 10.1016/s0926-6585(96)90019-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chamberlain AK, Bowie JU. Evaluation of C-H cdots, three dots, centered O hydrogen bonds in native and misfolded proteins. J Mol Biol. 2002;322(3):497–503. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00785-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartlett GJ, Choudhary A, Raines RT, Woolfson DN. n→pi* interactions in proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6(8):615–620. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Karandur D, Wong KY, Pettitt BM. Solubility and aggregation of Gly(5) in water. J Phys Chem B. 2014;118(32):9565–9572. doi: 10.1021/jp503358n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lattman EE, Rose GD. Protein folding—what’s the question? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90(2):439–441. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pauling L, Corey RB. Configurations of polypeptide chains with favored orientations around single bonds: Two new pleated sheets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1951;37(11):729–740. doi: 10.1073/pnas.37.11.729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pauling L, Corey RB, Branson HR. The structure of proteins; two hydrogen-bonded helical configurations of the polypeptide chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1951;37(4):205–211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.37.4.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kauzmann W. Some factors in the interpretation of protein denaturation. Adv Protein Chem. 1959;14:1–63. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60608-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dill KA. Dominant forces in protein folding. Biochemistry. 1990;29(31):7133–7155. doi: 10.1021/bi00483a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Baldwin RL. The new view of hydrophobic free energy. FEBS Lett. 2013;587(8):1062–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Makhatadze GI, Privalov PL. Energetics of protein structure. Adv Protein Chem. 1995;47:307–425. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60548-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berezovsky IN, Chen WW, Choi PJ, Shakhnovich EI. Entropic stabilization of proteins and its proteomic consequences. PLoS Comput Biol. 2005;1(4):e47. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gokce I, Woody RW, Anderluh G, Lakey JH. Single peptide bonds exhibit poly(pro)II (“random coil”) circular dichroism spectra. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127(27):9700–9701. doi: 10.1021/ja052632x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Woody RW. Circular dichroism spectrum of peptides in the poly(Pro)II conformation. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131(23):8234–8245. doi: 10.1021/ja901218m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mezei M, Fleming PJ, Srinivasan R, Rose GD. Polyproline II helix is the preferred conformation for unfolded polyalanine in water. Proteins. 2004;55(3):502–507. doi: 10.1002/prot.20050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Graf J, Nguyen PH, Stock G, Schwalbe H. Structure and dynamics of the homologous series of alanine peptides: A joint molecular dynamics/NMR study. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129(5):1179–1189. doi: 10.1021/ja0660406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matthews BW, Nicholson H, Becktel WJ. Enhanced protein thermostability from site-directed mutations that decrease the entropy of unfolding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84(19):6663–6667. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ting D, et al. Neighbor-dependent Ramachandran probability distributions of amino acids developed from a hierarchical Dirichlet process model. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6(4):e1000763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chan HS. Modeling protein density of states: Additive hydrophobic effects are insufficient for calorimetric two-state cooperativity. Proteins. 2000;40(4):543–571. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20000901)40:4<543::aid-prot20>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chan HS, Zhang Z, Wallin S, Liu Z. Cooperativity, local-nonlocal coupling, and nonnative interactions: Principles of protein folding from coarse-grained models. Annu Rev Phys Chem. 2011;62:301–326. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physchem-032210-103405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jewett AI, Pande VS, Plaxco KW. Cooperativity, smooth energy landscapes and the origins of topology-dependent protein folding rates. J Mol Biol. 2003;326(1):247–253. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01356-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Badasyan A, Liu Z, Chan HS. Probing possible downhill folding: Native contact topology likely places a significant constraint on the folding cooperativity of proteins with approximately 40 residues. J Mol Biol. 2008;384(2):512–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shimizu S, Chan HS. Anti-cooperativity and cooperativity in hydrophobic interactions: Three-body free energy landscapes and comparison with implicit-solvent potential functions for proteins. Proteins. 2002;48(1):15–30. doi: 10.1002/prot.10108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Z, Chan HS. Desolvation is a likely origin of robust enthalpic barriers to protein folding. J Mol Biol. 2005;349(4):872–889. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chan HS, Shimizu S, Kaya H. Cooperativity principles in protein folding. Methods Enzymol. 2004;380:350–379. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)80016-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Plaxco KW, Simons KT, Baker D. Contact order, transition state placement and the refolding rates of single domain proteins. J Mol Biol. 1998;277(4):985–994. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Impey RW, Klein ML. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J Comput Chem. 1983;79(2):926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Phillips JC, et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. J Comput Chem. 2005;26(16):1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Best RB, et al. Optimization of the additive CHARMM all-atom protein force field targeting improved sampling of the backbone φ, ψ and side-chain χ(1) and χ(2) dihedral angles. J Chem Theory Comput. 2012;8(9):3257–3273. doi: 10.1021/ct300400x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brooks BR, et al. CHARMM: The biomolecular simulation program. J Comput Chem. 2009;30(10):1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cossi MBV, Cammi R, Tomasi J. Ab initio study of solvated molecules: A new implementation of the polarizable continuum model. Chem Phys Lett. 1996;255(4):327–335. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fox NK, Brenner SE, Chandonia JM. SCOPe: Structural Classification of Proteins—extended, integrating SCOP and ASTRAL data and classification of new structures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(Database issue):D304–D309. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]