Significance

The integration of genetically programmed cells into materials and devices will enable the power of biology to be harnessed for a wide range of scientific research and technological applications. Here, we use stretchable, robust, and biocompatible hydrogel–elastomer hybrids to host genetically programed bacteria, thus creating a set of stretchable and wearable living materials and devices that possesses unprecedented functions and capabilities. A quantitative yet generic model is further developed to account for the coupled physical and biochemical processes in living materials and devices. This simple strategy for designing living materials and devices not only provides tools for research in synthetic biology but also, enables applications, such as living sensors, interactive genetic circuits, and living wearable devices.

Keywords: hydrogels, synthetic biology, genetically engineered bacteria, biochemical sensors, wearable devices

Abstract

Living systems, such as bacteria, yeasts, and mammalian cells, can be genetically programmed with synthetic circuits that execute sensing, computing, memory, and response functions. Integrating these functional living components into materials and devices will provide powerful tools for scientific research and enable new technological applications. However, it has been a grand challenge to maintain the viability, functionality, and safety of living components in freestanding materials and devices, which frequently undergo deformations during applications. Here, we report the design of a set of living materials and devices based on stretchable, robust, and biocompatible hydrogel–elastomer hybrids that host various types of genetically engineered bacterial cells. The hydrogel provides sustainable supplies of water and nutrients, and the elastomer is air-permeable, maintaining long-term viability and functionality of the encapsulated cells. Communication between different bacterial strains and with the environment is achieved via diffusion of molecules in the hydrogel. The high stretchability and robustness of the hydrogel–elastomer hybrids prevent leakage of cells from the living materials and devices, even under large deformations. We show functions and applications of stretchable living sensors that are responsive to multiple chemicals in a variety of form factors, including skin patches and gloves-based sensors. We further develop a quantitative model that couples transportation of signaling molecules and cellular response to aid the design of future living materials and devices.

Genetically engineered cells enabled by synthetic biology have accomplished multiple programmable functions, including sensing (1), responding (2), computing (3), and recording (4). Powered by this emerging capability to program cells into living computers (1–6), the integration of genetically encoded cells into freestanding materials and devices will not only provide new tools for scientific research but also, lead to unprecedented technological applications (7). However, the development of such living materials and devices has been significantly hampered by the demanding requirements for maintaining viable and functional cells in materials and devices plus biosafety concerns toward the release of genetically modified organisms into environments. For example, gene networks embedded in paper matrices have been used for low-cost rapid viruses detection and protein manufacturing (1). However, their gene networks are based on freeze-dried extracts from genetically engineered cells to operate, partially because the paper substrates cannot sustain long-term viability and functionality of living cells or prevent their leakage. As another example, by seeding cardiomyocytes on thin elastomer films, biohybrid devices have been developed as soft actuators (8) and biomimetic robots (9). However, because the cells are not protected or isolated from the environment, the biohybrid devices need to operate in media, and the cells may detach from the elastomer films. Thus, it remains a grand challenge to integrate genetically encoded cells into practical materials and devices that can maintain long-term viability and functionality of the cells, allow for efficient chemical communications between cells and with external environments, and prevent cells from escaping the materials or devices. A versatile material system and a general method to design living materials and devices capable of diverse functions (1, 8–10) remain a critical need in the field.

As polymer networks infiltrated with water, hydrogels have been widely used as scaffolds for tissue engineering (11) and vehicles for cell delivery (12) owing to their high water content, biocompatibility, biofunctionality, and permeability to a wide range of chemicals and biomolecules (13). The success of hydrogels as cell carriers in tissue engineering and cell delivery shows their potential as an ideal matrix for living materials and devices to incorporate genetically engineered cells. However, common hydrogels exhibit low mechanical robustness (14) and difficulty in bonding with other materials and devices (15), which have posed challenges in using them as matrices for living materials and devices (10). Significant progress has been made toward designing hydrogels with high mechanical toughness and stretchability (14, 16, 17) and robustly bonding hydrogels to engineering materials, such as glass, ceramics, metals, and elastomers (15, 18, 19). Combining programmed cells with robust biocompatible hydrogels has the potential to enable an avenue to create new living materials and devices, but this promising approach has not been explored yet.

Here, we show the design of a set of living materials and devices based on stretchable, robust, and biocompatible hydrogel–elastomer hybrids that host various types of genetically engineered bacterial cells. We show that our hydrogels can sustainably provide water and nutrients to the cells, whereas our elastomers ensure sufficient air permeability to maintain viability and functionality of the bacteria. Communication between different types of genetically engineered cells and with the environment is achieved via transportation of signaling molecules in hydrogels. The high stretchability and robustness of the hydrogel–elastomer hybrids prevent leakage of cells from the living materials and devices under repeated deformations. We show applications uniquely enabled by our living materials and devices, including stretchable living sensors responsive to multiple chemicals, interactive genetic circuits, a living patch that senses chemicals on the skin, and a glove with living chemical detectors integrated at the fingertips. A quantitative model that couples transportation of signaling molecules and responses of cells is further developed to help the design of future living materials and devices.

Results

Design of Living Materials and Devices.

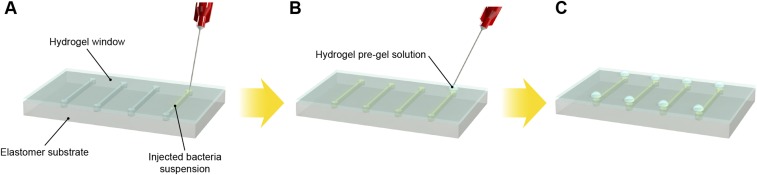

We propose that encapsulating genetically engineered cells in biocompatible, stretchable, and robust hydrogel–elastomer hybrid matrices represents a general strategy for the design of living materials and devices with powerful properties and functions. The design of a generic structure for the living materials and devices is illustrated in Fig. 1A. In brief, layers of robust and biocompatible hydrogel and elastomer were assembled and bonded into a hybrid structure (15). Patterned cavities of different shapes and sizes were introduced on the hydrogel–elastomer interfaces to host living cells in subsequent steps. The hydrogel–elastomer hybrid was then immersed in culture media for 12 h, so that the hydrogel can be infiltrated with nutrients. Thereafter, genetically engineered bacteria suspended in media were infused into the patterned cavities through the hydrogel, and the injection points were then sealed with drops of fast-curable pregel solution (Fig. S1). Because the hydrogel was infiltrated with media and the elastomer is air-permeable, hydrogel–elastomer hybrids with proper dimensions can provide sustained supplies of water, nutrient, and oxygen (if needed) to the cells. By tuning the dimensions of hydrogel walls between different types of cells and between cells and external environments, we can control the transportation times of signaling molecules for cell communication. Furthermore, the high mechanical robustness of the hydrogel, elastomer, and their interface confers structural integrity to the matrix even under large deformations, thus preventing cell escape in dynamic environments.

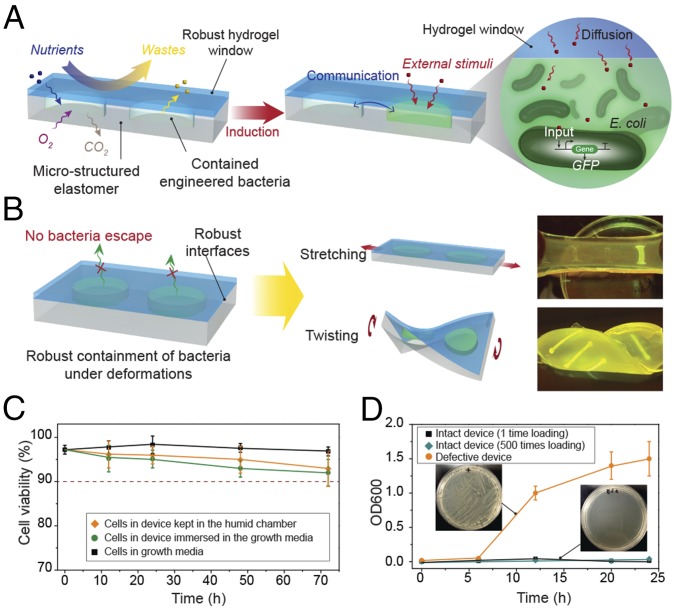

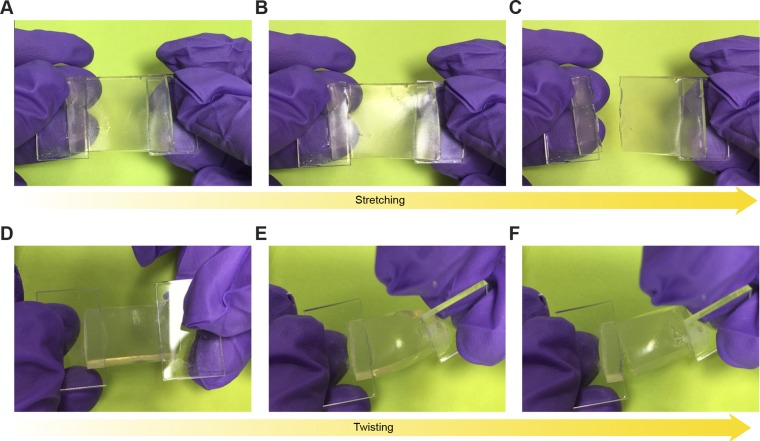

Fig. 1.

Design of living materials and devices. (A) Schematic illustration of a generic structure for living materials and devices. Layers of robust and biocompatible hydrogel and elastomer were assembled and bonded into a hybrid structure, which can transport sustained supplies of water, nutrient, and oxygen to genetically engineered cells at the hydrogel–elastomer interface. Communication between different types of cells and with the environment was achieved by diffusion of small molecules in hydrogels. (B) Schematic illustration of the high stretchability and high robustness of the hydrogel–elastomer hybrids that prevent cell leakage from the living device, even under large deformations. Images show that the living device can sustain uniaxial stretching over 1.8 times and twisting over 180° while maintaining its structural integrity. (C) Viability of bacterial cells at room temperature over 3 d. The cells were kept in the device placed in the humid chamber without additional growth media (yellow), in the device immersed in the growth media as a control (green), and in growth media as another control (black; n = 3 repeats). (D) OD600 and (Insets) streak plate results of the media surrounding the defective devices (yellow) and intact devices at different times after 1 (black) or 500 times (green) deformation of the living devices and immersion in media (n = 3 repeats).

Fig. S1.

Schematic illustration of cell suspension injection and sealing of injection points. (A) Bacteria were injected into the cavities at the hydrogel–elastomer interface with metallic needles from the hydrogel side. (B) Injection holes were sealed on the hydrogel–elastomer device with drops of fast-curable pregel solution. (C) We obtained the hydrogel–elastomer device with fully encapsulate bacteria.

In this study, we chose polyacrylamide (PAAm)-alginate hydrogel (15, 17) and polydimethylsiloxane (Sylgard 184; Dow Corning) or Ecoflex (Smooth-On) silicone elastomer to constitute the robust hydrogel and elastomer, respectively. The biocompatibility of these materials has been extensively validated in various biomedical applications (20, 21). The sufficient gas permeation of the silicone elastomer enables oxygen supply for the bacteria (22–24). If a higher level of oxygen is required, one may choose elastomers with higher permeability, such as Silbione (25), or microporous elastomers (23). In the hydrogel, the covalently cross-linked PAAm network is highly stretchable, and the reversibly cross-linked alginate network dissipates mechanical energy under deformation, leading to tough and stretchable hydrogels (14, 17, 26). More robust devices can be fabricated by using fiber-reinforced tough hydrogel (27). Robust bonding between the hydrogel and elastomer can be achieved by covalently anchoring the PAAm network on the elastomer substrate (15, 18, 26). The Escherichia coli bacterial strains were engineered to produce outputs [e.g., expressing GFP (green fluorescent protein)] under control of promoters that are inducible by cognate chemicals. For example, the 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinolReceiver (DAPGRCV)/GFP strain produces GFP when the chemical inducer DAPG is added and received by the cells. The cell strains used in this study included DAPGRCV/GFP, N-acyl homoserine lactoneRCV (AHLRCV)/GFP, isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranosideRCV (IPTGRCV)/GFP, rhamnoseRCV (RhamRCV)/GFP, and anhydrotetracyclineRCV (aTcRCV)/AHL. The DAPG, AHL, IPTG, Rham, and aTc are small molecules with biochemical activities and used as the signaling molecules in this study.

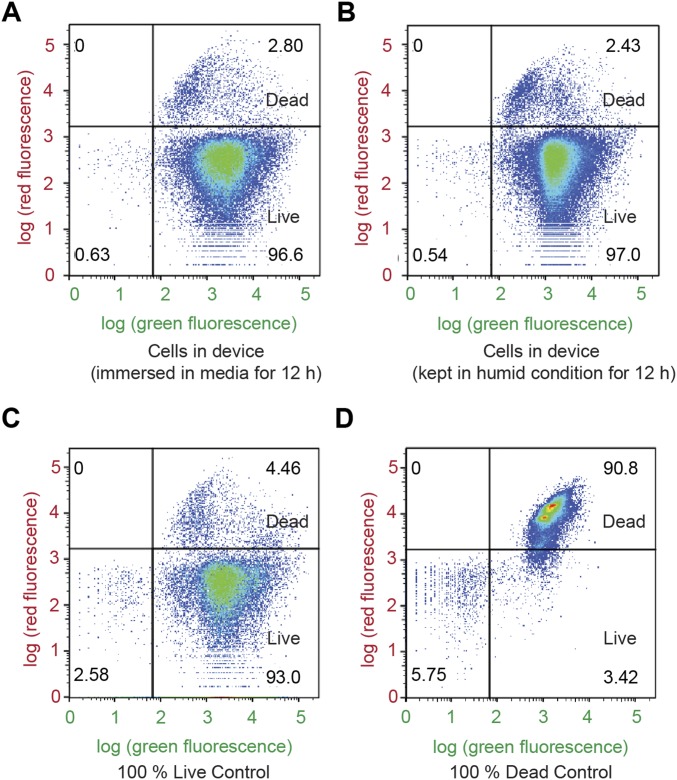

To evaluate the viability of cells in living materials and devices, we placed the hydrogel–elastomer matrices containing RhamRCV/GFP cells (Fig. 1A) in a humid chamber (relative humidity > 90%) without addition of growth media or immersed the living materials in the growth media at room temperature (25 °C) for 3 d. We also directly cultured the cells in growth media as a control. Thereafter, we used the live/dead stain and performed flow cytometry analysis for bacteria retrieved from the living device to test the cell viability. As shown in Fig. 1C and Fig. S2, the viability of cells in the device placed in a humid chamber maintains above 90% over 3 d without addition of media to the device. This viability is similar to that of cells in the device immersed in media or cells directly cultured in media at room temperature over 3 d.

Fig. S2.

Flow cytometry analysis using live/dead stains for (A) cells retrieved from the living device that has been immersed in media for 12 h, (B) cells retrieved from the living device that has been placed in humid environment for 12 h, (C) live-cell controls, and (D) dead-cell controls. Green fluorescence denotes both live and dead bacteria, and red fluorescence denotes bacteria that have been damaged and leaky membranes. The distributions of the live and dead populations are illustrated in the plots, with thresholds determined by controls. Over 95% of cells in the hydrogel–elastomer devices immersed in media or placed in humid chamber remained viable after 12 h.

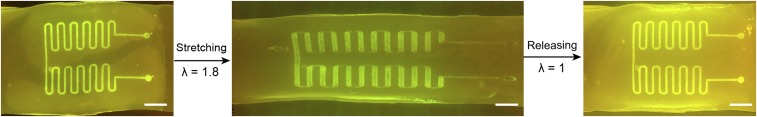

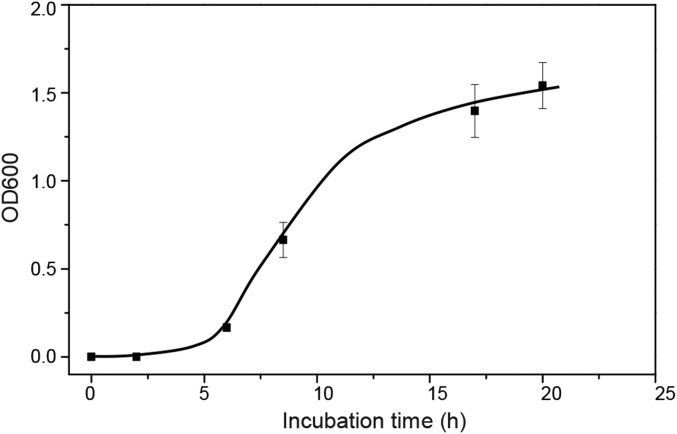

To test whether bacteria could escape from the living devices, we deformed the hydrogel–elastomer hybrids containing RhamRCV/GFP bacteria in different modes (i.e., stretching and twisting) as illustrated in Fig. 1B, and then immersed the device in media for a 24-h period. As shown in Fig. 1B and Fig. S3, the living device made of Ecoflex and tough hydrogel sustained a uniaxial stretch over 1.8 times its original length and a twist over 180° while maintaining its structural integrity. Furthermore, after immersing the device in media for 6, 12, 20, and 24 h, we collected the media surrounding the device and measured the cell population in the media over time via OD600 by UV spectroscopy (Fig. 1D); 200 μL media were streaked on agar plates after 24 h to check for cell escape and growth (Fig. 1D, Insets). Fig. 1D shows that bacteria did not escape the hydrogel–elastomer hybrid even under repeated mechanical loads (500 cycles). As controls, we intentionally created defective devices (with weak hydrogel–elastomer bonding) and observed significant escape and overgrowth of bacteria after immersing the samples in media (yellow curve in Fig. 1D). Because agar hydrogels have been widely used for cell encapsulation, we fabricated an agar-based control device that encapsulated RhamRCV/GFP bacteria with the same dimensions as the hydrogel–elastomer hybrid. In Fig. S4, it can be seen that these agar devices underwent failures even under moderate deformation (e.g., a stretch of 1.1 or a twist of 60°). Moreover, cell leakage from the agar devices occurred regardless of the presence of any deformation, likely because of the large pore sizes and sol–gel transition of the agar gel, allowing for escape of encapsulated bacteria (Fig. S5). These results indicate that our hydrogel–elastomer hybrids can provide a biocompatible, stretchable, and robust host for genetically engineered bacteria.

Fig. S3.

Functional living device under large uniaxial stretch. After GFP was switched on in the wavy channels of Ecoflex–hydrogel hybrid matrix, the device was stretched to 1.8 times its original length and then released. The device, including cells encapsulated, can maintain functionality under large deformation without failure or leakage. (Scale bar: 5 mm.)

Fig. S4.

Deformation of agar-based living devices. An agar-based control device that encapsulated RhamRCV/GFP bacteria with the same dimensions as the hydrogel–elastomer hybrid was fabricated. The agar device fractured even under moderate deformation, including (A–C) a stretch of 1.1 or (D–F) a twist of 60°.

Fig. S5.

Cell leakage from the agar device. The medium surrounding the agar device (without any deformation) was collected to measure OD600. The high OD600 after 10 h indicates the large cell populations in the medium and cell leakage even without any deformation of agar gel.

Stretchable Living Sensors for Chemical Sensing.

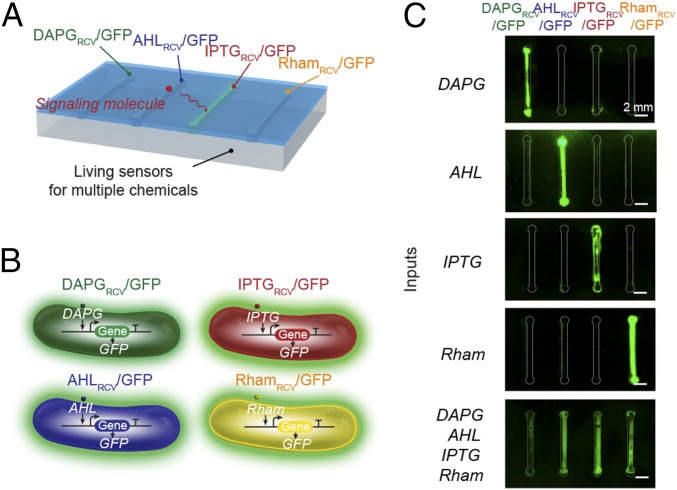

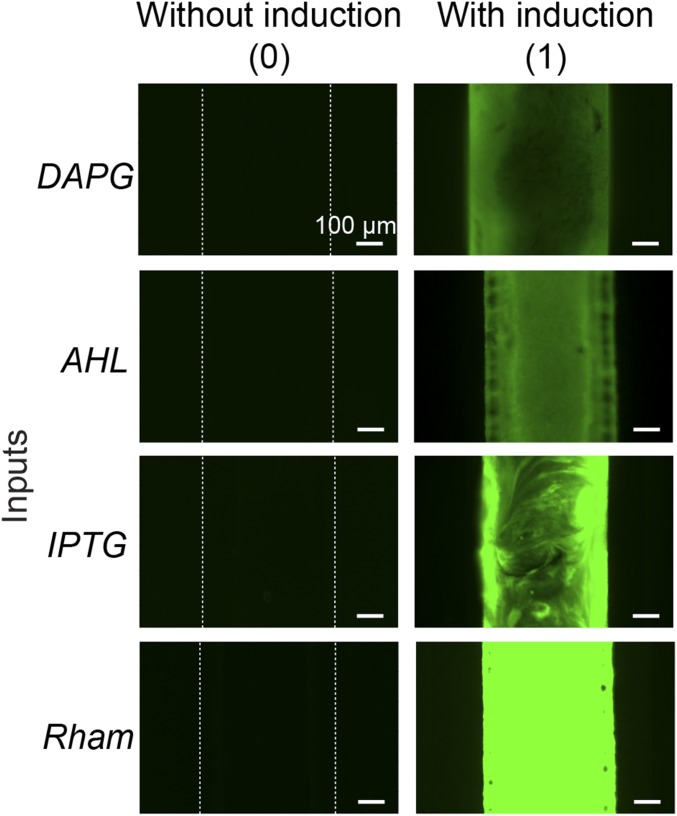

We next show functions and applications enabled by the living materials and devices. Fig. 2A illustrates a hydrogel–elastomer hybrid with four isolated chambers that each hosted a different bacterial strain: DAPGRCV/GFP, AHLRCV/GFP, IPTGRCV/GFP, and RhamRCV/GFP. The genetic circuits in these bacterial strains can sense their cognate inducers and express GFP (Fig. S6), which can be visible under blue light illumination. As mentioned above, the DAPGRCV/GFP strain exhibits green fluorescence when receiving DAPG but is not responsive to other stimuli. Similarly, the AHLRCV/GFP strain expresses GFP only induced by AHL, IPTG selectively induces GFP expression in the IPTGRCV/GFP strain, and Rham selectively induces the green fluorescence output of the RhamRCV/GFP strain (Fig. 2B). We show that each inducer, diffusing from the environment through the hydrogel into cell chamber, can trigger GFP expression of its cognate strain inside the device, which could be visualized by the naked eye or microscope (Fig. 2C and Fig. S7). This orthogonality makes the hydrogel–elastomer hybrid with encapsulated bacteria into a living sensor that can simultaneously detect multiple chemicals in the environment (Fig. 2C). About 2 h are required for each strain to produce significant fluorescence. Parameters that affect response times for the living sensor are discussed with a quantitative model below.

Fig. 2.

Stretchable living sensors can independently detect multiple chemicals. (A) Schematic illustration of a hydrogel–elastomer hybrid with four isolated chambers to host bacterial strains, including DAPGRCV/GFP, AHLRCV/GFP, IPTGRCV/GFP, and RhamRCV/GFP. Signaling molecules were diffused from the environment through the hydrogel window into cell chambers, where they were detected by the bacteria. (B) Genetic circuits were constructed in bacterial strains to detect cognate inducers (i.e., DAPG, AHL, IPTG, and Rham) and produce GFP. (C) Images of living devices after exposure to individual or multiple inputs. Cell chambers hosting bacteria with the cognate sensors showed green fluorescence, whereas the noncognate bacteria in chambers were not fluorescent. Scale bars are shown in images.

Fig. S6.

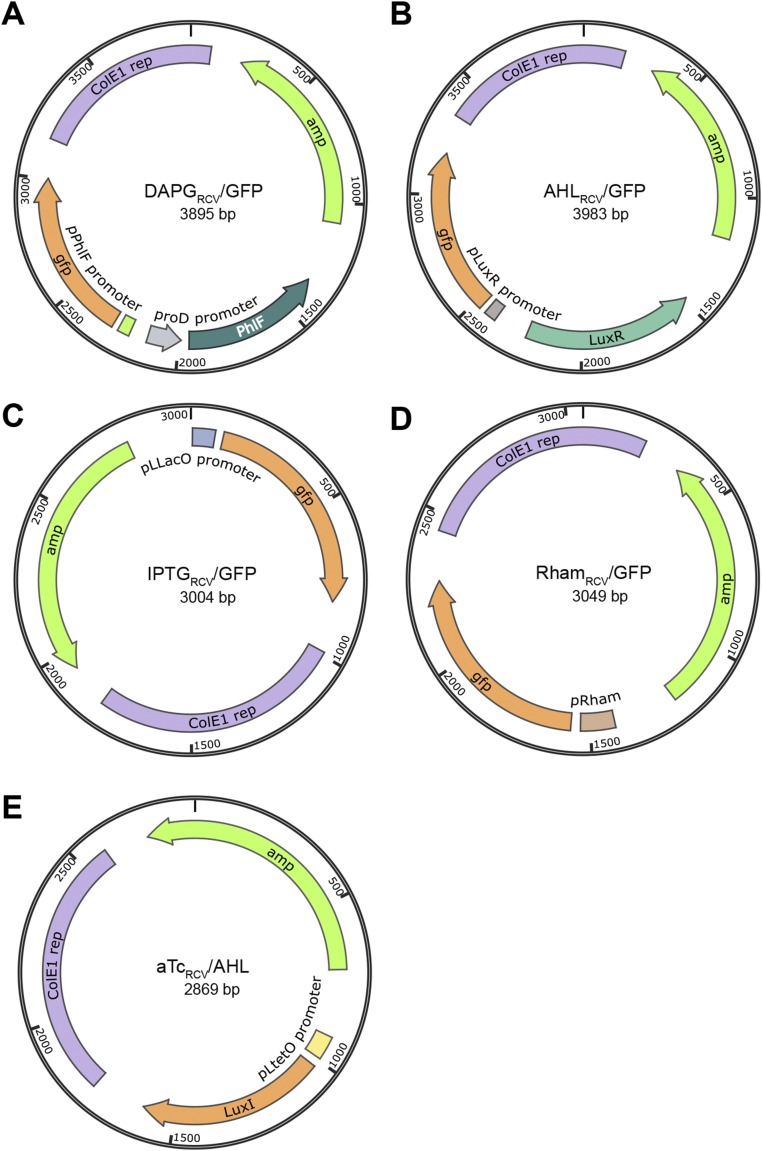

Plasmid maps of the plasmids constructed. (A) DAPGRCV/GFP, (B) AHLRCV/GFP, (C) IPTGRCV/GFP, (D) RhamRCV/GFP, and (E) aTcRCV/AHL. Plasmids were constructed as described in SI Text. amp, Ampicillin resistance gene; ColE1 rep:, replication origin from ColE1 plasmid.

Fig. S7.

Microscopic images of different cell strains in the chamber encapsulated in the living device. When a cell strain was induced, the channels showed fluorescence [denoted as (1)]. If not induced, the channel stayed dark [denoted as (0)]. Scale bars are shown in images.

Interactive Genetic Circuits.

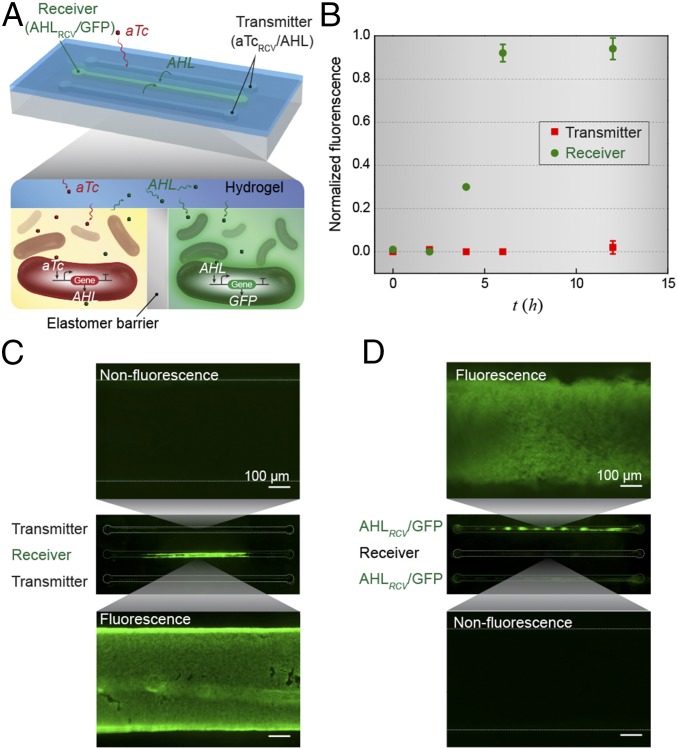

Next, we integrated cells containing different genetic circuits into a freestanding living device to study cellular signaling cascades. We designed two bacterial strains that can communicate via the diffusion of signaling molecules through the hydrogel, although both were separated by an elastomer barrier within discrete chambers of the device (Fig. 3A). Specifically, we used a transmitter strain (aTcRCV/AHL) that produces the quorum-sensing molecule AHL when induced by aTc and a receiver strain (AHLRCV/GFP) with AHL-inducible GFP genes (5). We triggered this device with aTc from the environment to induce the transmitter cells, which resulted in AHL production and stimulation of receiver cells to synthesize GFP (Fig. 3C). In Fig. 3B, we plot the normalized fluorescence of bacteria in different cell chambers (i.e., transmitter and receiver in Fig. 3A) as a function of time after aTc was added outside the device. Because there is no GFP gene in the transmitter cells (aTcRCV/AHL), their chambers showed no fluorescence over time (Fig. 3B). It took longer response time (∼5 h) for the receiver cells in the middle chamber to exhibit significant fluorescence compared with the cells in simple living sensors (Fig. 2A). Two diffusion processes (i.e., aTc from the environment to the two side chambers and AHL from the two side chambers to the central chamber) and two induction processes (i.e., AHL production induced by aTc in transmitters and GFP expression induced by AHL in receivers) were involved in the current interactive genetic circuits. As a control, when the transmitters (aTcRCV/AHL) in the device were replaced by a cell strain containing aTc-inducible GFP (aTcRCV/GFP) that cannot communicate with AHLRCV/GFP, no fluorescence was observed in the receiver (AHLRCV/GFP) chamber (Fig. 3D). Overall, the integrated devices containing interactive genetic circuits provide a platform for the detection of various chemicals and the investigation of cellular interaction among physically isolated cell populations.

Fig. 3.

Interactive genetic circuits. (A) Schematic illustration of a living device that contains two cell strains: the transmitters (aTcRCV/AHL strain) produce AHL in the presence of aTc, and the receivers (AHLRCV/GFP strain) express GFP in the presence of AHL. The transmitters could communicate with the receivers via diffusion of the AHL signaling molecules through the hydrogel window, although the cells are physically isolated by elastomer. (B) Quantification of normalized fluorescence over time (n = 3 repeats). All data were measured by flow cytometry, with cells retrieved from the device at different times. (C) Images of device and microscopic images of cell chambers 6 h after addition of aTc into the environment surrounding the device. The side chambers contain transmitters, whereas the middle one contains receivers. (D) Images of device and microscopic images of cell chambers 6 h after aTc addition in the environment. The side chambers contain aTcRCV/GFP instead of transmitters, whereas the middle one contains receivers. Scale bars are shown in images.

Living Wearable Devices.

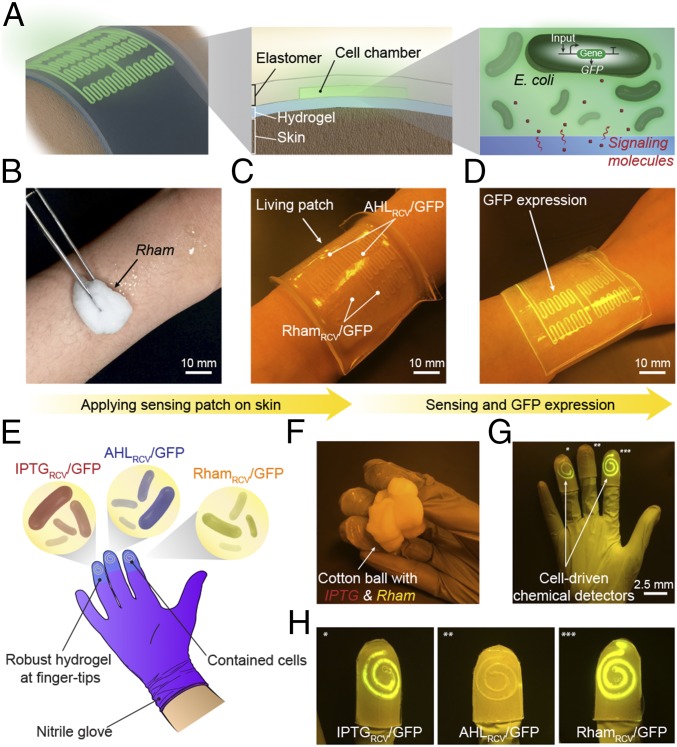

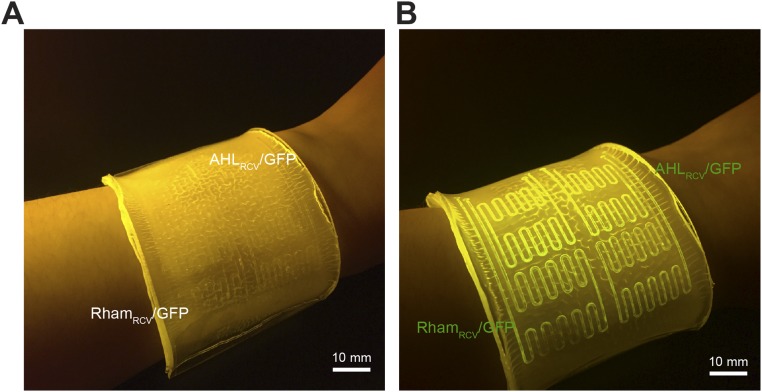

To further show practical applications of living materials and devices, we fabricated a living wearable patch that detects chemicals on the skin (Fig. 4 A–D). The sensing patch matrix consists of a bilayer hybrid structure of tough hydrogel and silicone elastomer. The wavy cell channels could cover a larger area of the skin with a limited amount of bacterial cells (Fig. 4A). The living patch can be fixed on the skin by clear Scotch tape, with the hydrogel exposed to the skin and the elastomer exposed to the air. The compliance and stickiness of the hydrogel promote conformal attachment of the living patch to human skin, whereas the silicone elastomer cover effectively prevents the dehydration of the sensor patch (Fig. S8) (15). As shown in Fig. 4 B–D, the inducer Rham was smeared on the skin of a forearm before we adhered the living patch. The channels with RhamRCV/GFP in the living patch became fluorescent within 4 h, whereas channels with AHLRCV/GFP did not show any difference. As controls, no fluorescence was observed in any channels in absence of any inducer on the skin (Fig. S9A), whereas all channels became fluorescent in presence of both AHL and Rham (Fig. S9B). Although the inducers are used as mock biomarkers here, more realistic chemical detections, such as components in human sweat or blood, may be pursued with living devices for scientific research and translational medicine in the future.

Fig. 4.

Living wearable devices. (A) Schematic illustration of a living patch. The patch adhered to the skin with the hydrogel side, and the elastomer side was exposed to the air. Engineered bacteria inside can detect signaling molecules. (B–D) Rham solution was smeared on skin, and the sensor patch was conformably applied on skin. The channels with RhamRCV/GFP in the living patch became fluorescent, whereas channels with AHLRCV/GFP did not show any differences. Scale bars are shown in images. (E) Schematic illustration of a glove with chemical detectors robustly integrated at the fingertips. Different chemical-inducible cell strains, including IPTGRCV/GFP, AHLRCV/GFP, and RhamRCV/GFP, were encapsulated in the chambers. (F–H) When the living glove was used to grab a wet cotton ball containing the inducers, GFP fluorescence was shown in the cognate sensors IPTGRCV/GFP (*) and RhamRCV/GFP (***) on the gloves. In contrast, the noncognate sensor AHLRCV/GFP (**) did not show any fluorescence. Scale bars are shown in images.

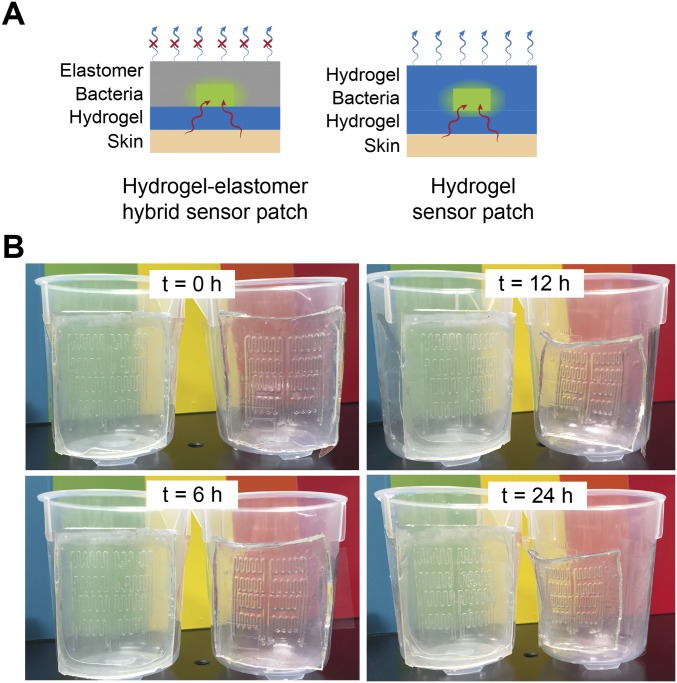

Fig. S8.

Antidehydration property of the sensor patch. (A) Schematic illustration of the hydrogel–elastomer hybrid sensor patch, which has the antidehydration property over the pure hydrogel device. The silicone elastomer cover effectively prevents evaporation of water from the hydrogel and dehydration of the living patch. (B) Time-lapse snapshots of hydrogel–elastomer hybrid sensor patch (Left) and pure hydrogel sensor patch (Right) mounted on a plastic beaker at room temperature with low humidity (25 °C and 50% relative humidity) for 24 h. The elastomer outer layer of the hydrogel–elastomer hybrid device significantly slowed down the dehydration process of the hydrogel and provided a sustained humid environment for encapsulated cells for over 24 h. However, distorted channels became apparent on patches made of pure hydrogels when they were exposed to air for 6 h because of dehydration.

Fig. S9.

Living patch control experiments. (A) When no inducer was smeared on skin and the living sensor patch was adhered on skin conformably, the channels with RhamRCV/GFP and AHLRCV/GFP in the living patch did not show any differences. (B) When both inducers Rham and AHL were smeared on skin and the living patch was applied, the channels with RhamRCV/GFP and AHLRCV/GFP in the living patch became fluorescent. Scale bars are shown in images.

As another application, a glove with chemical detectors integrated at the fingertips was fabricated (Fig. 4E). The stretchable hydrogel and tough bonding between hydrogel and rubber allow for robust integration of living monitors on flexible gloves. To show the capability of this living glove, a glove-wearer held cotton balls that have absorbed inducers. Those chemicals from the cotton ball would diffuse through the hydrogel and induce fluorescence in the engineered bacteria (Fig. 4 F–H). For example, gripping a wet cotton ball that contained IPTG and Rham resulted in fluorescence at two of three bacterial sensors that contained IPTGRCV/GFP (Fig. 4 G and H, *) and RhamRCV/GFP (Fig. 4 G and H, ***) on the glove within 4 h. The middle sensor containing AHLRCV/GFP (Fig. 4 G and H, **) remained unaffected. The living patch and biosensing glove show the potential of living materials as low-cost and mechanically flexible platforms for healthcare and environmental monitoring. Looking forward, we envision the design of living devices that can be wearable, ingestible, or implantable for applications, such as water quality alert, disease diagnostics, and therapy.

Discussion and Modeling

Model of Living Materials and Devices.

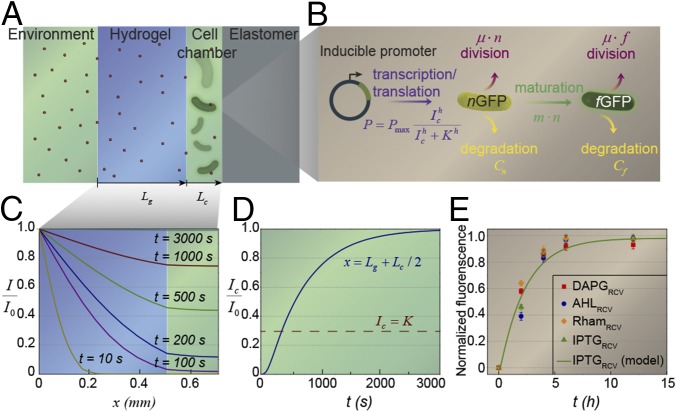

In this section, we developed a model that quantitatively accounted for the coupled physical transportation and biochemical responses underlying the living sensor (Fig. 2). The operation of the living sensor (Fig. 2A) relied on two processes: diffusion of signaling molecules from the environment through the hydrogel window into cell chambers and induction of the encapsulated cells by the signaling molecules (28). Given the geometry of the senor (Fig. 5A), we could approximate the transportation of inducer in the hydrogel and the cell chamber to follow the 1D Fick’s law:

| [1] |

and

| [2] |

where is the coordinate of a point in the hydrogel window or the cell chamber; and are the thicknesses of the hydrogel and cell chamber, respectively; is the current time; is the inducer concentration in hydrogel or medium in the cell chamber; and and are the diffusion coefficients of the inducer in hydrogel and medium, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Model for the diffusion–induction process in living materials and devices. (A) Schematic illustration of the diffusion of signaling molecules from the environment through the hydrogel to cell chambers in the living device. (B) Diagram of GFP expression after induction with a small molecule chemical. (C) Inducer concentration profile throughout the hydrogel window and cell chamber at different times. (D) Typical inducer concentration in the cell chamber as a function of time. (E) The normalized fluorescence of different cell strains as a function of time after addition of inducer (n = 3 repeats). Dots represent experimental data, and curve represents the model.

To prescribe boundary conditions for Eqs. 1 and 2, the inducer concentration at the boundary between the environment and the hydrogel window is taken to be a constant , the inducer concentration and inducer flux are taken to be continuous across the interface between the hydrogel and cell chamber, and the elastomer wall of the cell chamber is taken to be impermeable to the inducers. Because the diffusion process begins at , the inducer concentration throughout the hydrogel window and cell chamber is zero when as the initial condition for Eqs. 1 and 2. Furthermore, the consumption of inducers by the bacterial cells was taken to be negligible. In these experiments, we set , , and for IPTG diffusion–induction. The diffusion coefficients of inducers are estimated to be and based on previous measurements (29).

The diffusion equations together with boundary and initial conditions were solved numerically. In Fig. 5C, we plot the inducer concentrations throughout the hydrogel window and cell chamber at different times. It can be seen that the distribution of inducers in the cell chamber is more uniform than that in the hydrogel because of the higher inducer diffusion coefficient in media than that in hydrogel. We further define the typical inducer concentration as the inducer concentration at the center of the cell chamber [i.e., ]. In Fig. 5D, we plot the typical inducer concentration in the cell chamber as a function of time.

To characterize the GFP expression of the bacterial cells in the living sensor, we adopt a model from Leveau and Lindow (30). The inducers can bind with repressors or activators in a bacterial cell and induce the transcription of promoters. The induced promoters initiate the synthesis of nonfluorescent GFP (nGFP). Meanwhile, the nGFP in the cell is consumed because of the maturation into the fluorescent GFP (fGFP), cell division, and protein degradation. The converted fGFP also undergoes consumption because of cell division and protein degradation. Eventually, the syntheses and consumptions of nGFP and fGFP reach steady states in the cell (Fig. 5B). Denoting the numbers of nGFP and fGFP in a cell as and , respectively, their rates of variation can be approximated as

| [3] |

and

| [4] |

In Eqs. 3 and 4, is the promoter activity that expresses nGFP; prescribes the maturation rate of nGFP into fGFP, where is the maturation constant; and prescribe the consumption rates of nGFP and fGFP caused by cell division, respectively, where is the growth constant; and and are the degradation rates of nGFP and fGFP, respectively. The promoter activity for transcription and translation induced by an inducer is approximated by a Hill equation (31) , in which is the maximum rate of nGFP expression (i.e., maximum promoter activity), is the Hill coefficient, and is the half-maximal parameter (inducer concentration at which equals ). Because the inducer concentration in the cell chamber is relatively uniform (Fig. 5C), we take in the promoter activity expression to be the typical concentration in the cell chamber (i.e., ). Evidently, the connection between the transportation of inducers and biochemical responses of cells in the living sensor is through this Hill equation. Because the half-life of GFP in E. coli is over 24 h in absence of any proteolytic degradation, much longer than the typical responsive time of the living sensor, we assume throughout this study. For the IPTGRCV/GFP strain, we take , , , , and based on previously reported data on this system (30, 32).

In Fig. 5E, we plot the normalized fluorescence of cell in the device as a function of time after the inducers are added outside the living device. It takes around 2 h for different strains in the living sensor to show significant fluorescence (e.g., 0.5 of the maximum fluorescence). For the IPTGRCV/GFP strain, the diffusion–induction-coupled model matches very well with experimental data (Fig. 5E).

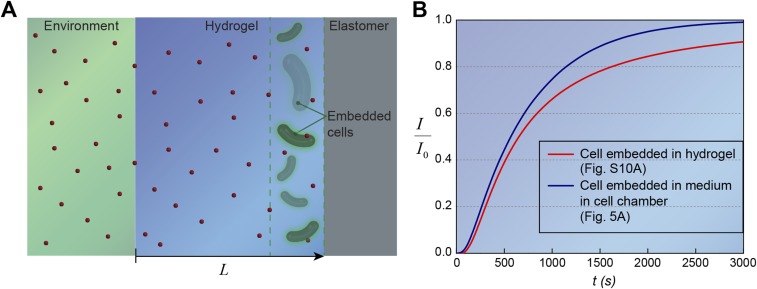

Critical Timescales for Living Materials and Devices.

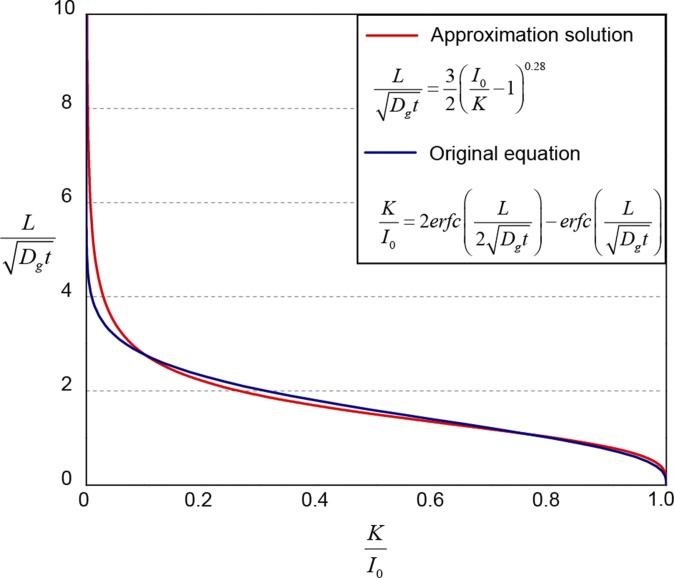

From the above analysis, we know that the responsive time of a living material or device is determined by two critical timescales: the time for inducers to diffuse and accumulate around cells to the level that is sufficient for induction and the time to induce GFP expression and reach a steady-state . To obtain analytical solutions for , we develop a simple but relevant model as illustrated in Fig. S10A. The model is similar to the geometry of the living sensor (Fig. 5A) but assumes that the cells are embedded in a segment of hydrogel close to the elastomer wall. The inducer concentration in the environment is taken to be constant , and the total thickness of the hydrogel is . By means of imaginary sources (33), the inducer concentration at location (at the end of hydrogel) and time can be expressed as , where is the complementary error function. From Fig. S10B, it can be seen that the simplified model can consistently represent the typical concentration profile in the cell chamber of the living sensor. From promoter activity expression, we assume that, only when the inducer concentration at a point reaches the level of (i.e., ), the inducer concentration is sufficient to induce the cells. Therefore, the critical diffusion time for cells with a typical distance from the environment is

| [5] |

where is the inverse of function of , is the typical diffusion timescale, and the prefactor accounts for the difference between and . We further fit the prefactor into a power law that approximately gives (Fig. S11).

Fig. S10.

Calculation of critical diffusion timescales for living materials and devices. (A) Schematic illustration of signaling molecule diffusion from the environment through the hydrogel in the living device. Cells were embedded in a segment of the hydrogel close to the elastomer wall. (B) Comparison of typical inducer concentration profiles when cells were embedded in hydrogel [] vs. cells in medium of the cell chamber []. Despite small deviation () because of the diffusivity differences between hydrogel and medium and distance variation in two cases, it can be seen that the profile in the simplified model can consistently represent the typical concentration profile in the cell chamber of the living sensor at any time.

Fig. S11.

Approximate diffusion timescale. The expression of and its approximate solution. The prefactor in is fitted into a power law that approximately gives .

We next evaluate the timescale to induce the cell . When the inducer concentration around a cell reaches the level of (i.e., reaches the level of ), significant induction (e.g., expression of GFP) will occur in the cell. To solve Eqs. 3 and 4 analytically, we assume that the induction happens only after reaches the level of and maintains at a constant level (between and ) during the induction. Therefore, we can set as the initial condition and as a time-independent constant in Eqs. 3 and 4. Further setting , we can obtain analytical solutions for nGFP and for fGFP, from which two characteristic timescales [i.e., and ] can be identified. Evidently, the characteristic timescale for the expression of nGFP is . Because the maturation constant is usually much larger than the growth constant (30, 34), the second term of fGFP has a much larger coefficient than the first term, and thus, the second term dominantly characterizes the expression of fGFP with a critical timescale of . Therefore, we approximate the critical time to induce cells to reach steady-state fluorescence as

| [6] |

Based on the known parameters for IPTGRCV/GFP cells encapsulated in hydrogel at a typical distance of (0.7 mm) from the environment, we can estimate the critical timescales of diffusion and induction to be and , respectively. The induction of cells takes a much longer time than the transportation of inducers, which is consistent with the full model (Fig. 5 D and E). In total, the coupled diffusion–induction timescale is , which is also in good agreement with the full model’s prediction (Fig. 5E).

The above analysis can provide a few guidelines for the design of future living materials. To design living materials and devices with faster responses, we need shorter times for both and . To decrease (Eq. 5), one can (i) reduce the thickness of the hydrogel, (ii) increase the diffusivity of inducer in the hydrogel, and (iii) increase the inducer concentration in the environment. However, to decrease , one can design cells with higher maturation constants or growth constants and add negative feedback into genetic circuit (31).

Conclusions

We have integrated genetically engineered cells as programmable functional components with stretchable, robust, and biocompatible hydrogel–elastomer hybrids to create a set of stretchable living materials and devices. These living materials and devices can be programmed with desirable functionalities by designing the genetic circuits in the cells as well as the structures and micropatterns of the hydrogel–elastomer hybrids. Moreover, we developed a quantitative model that accounts for the coupling between physical and biochemical processes in living materials. We further identified two critical timescales that determine the speed of response of the living materials and devices and provide guidelines for the design of future systems. This work has the potential to open technological avenues that capitalize on advances in synthetic biology and soft materials to implement stretchable, wearable, and portable living systems with important applications in the monitoring of human health (1) and environmental conditions (35) and the treatment and prevention of diseases (2).

Materials and Methods

All details associated with the materials, fabrication steps, and strain engineering appear in SI Text. Note that all procedures involving human subjects conformed to the guidelines for protecting the rights of human subjects and were approved by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects (COUHES protocol no. 1701827491). All subjects provided informed consent.

Briefly, different cell strains were picked from overnight growth on LB plates and cultured in LB with 50 μg/mL carbenicillin at 37 °C. Cell cultures (OD600 1) were infused into the patterned cavities between hydrogel and elastomer by metallic needles (Nordson EFD) through the hydrogel layer (Fig. S1). The holes induced by cell injection were sealed with small amounts of fast-curable pregel solution. The cell-contained device was washed with PBS three times followed by immersing the device in LB broth with carbenicillin and inducer(s) at 25 °C.

SI Text

Materials.

The hydrogel was composed of two types of cross-linked polymers: ionically cross-linked alginate and covalently cross-linked PAAm. For the stretchy PAAm network in hydrogel, acrylamide (AAm; A8887; Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the monomer, N,N-methylenebisacrylamide (MBAA; 146072; Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the cross-linker, and 2-hydroxy-4′-(2-hydroxyethoxy)-2-methylpropiophenone (Irgacure 2959; 410896; Sigma-Aldrich) was used as the photoinitiator. Calcium sulfate (C3771; Sigma-Aldrich) slurry acted as the ionic cross-linker with sodium alginate (A2033; Sigma-Aldrich) for the dissipative network. As for elastomers, Sylgard 184 [polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS; Dow Corning] or Ecoflex (Smooth-On) was molded and activated with benzophenone (B9300; Sigma-Aldrich). Purple Nitrile Examination Gloves (Kimberly-Clark) were also used as an elastomer substrate. Ammonium persulfate (APS; A3678; Sigma-Aldrich) as a thermoinitiator and N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED; T9281; Sigma-Aldrich) as a cross-linking accelerator were used in the fast-curable pregel solution for sealing of injection points. For cell induction, DAPG (sc-206518; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), AHL (K3007; Sigma-Aldrich), IPTG (I5502; Sigma-Aldrich), Rham (W373011; Sigma-Aldrich), and aTc (37919; Sigma-Aldrich) were used as the signaling molecules. Carbenicillin (C1389; Sigma-Aldrich) was added as an antibiotic in the LB–Miller medium (L3522; Sigma-Aldrich) for cell culture. The LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability and Counting Kit (L34856; Sigma-Aldrich) was used for cell viability assay.

Fabrication of Hydrogel and Elastomer Hybrid.

Elastomers with microstructured cavities were prepared by soft lithography with the feature size of 500 µm in width and 200 µm in depth. Then, the prepared microstructured elastomer was assembled with hydrogel to form robust hydrogel–elastomer hybrid as described in the previous report (15). Briefly, the surface of the elastomer was treated with 10% (wt/vol) benzophenone solution in ethanol for 10 min, washed, and dried with nitrogen. The pregel solution [12.05% (wt/vol) AAm, 1.95% (wt/vol) sodium alginate, 0.2% Irgacure 2959, 0.012% MBAA] was carefully degassed and mixed with calcium sulfate slurry (2 × 10−2 M in pregel solution) to form physically cross-linked hydrogel. To introduce robust bonding between assembled hydrogel and elastomer, the physically cross-linked hydrogel was assembled with the surface treated elastomer followed by UV irradiation (365 nm; UVP CL-1000) for 30 min. The resultant hydrogel–elastomer hybrid was washed with PBS for three times, sterilized using germicidal UV irradiation thoroughly, and immersed in LB with antibiotics for 12 h before bacterial cell seeding. Fast-curable pregel solution [30.05% (wt/vol) AAm, 1.95% (wt/vol) sodium alginate, 0.012% MBAA, 0.142% APS, 0.10% TEMED], which could be cured at room temperature in 5 min, is used for sealing the holes after cell seeding.

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids.

The plasmids used in this study were constructed with standard molecular cloning techniques. To create constructs for the expression of output genes under tight regulation by DAPG-, IPTG-, AHL-, or Rham-inducible promoters, pZE-AmpR-pL(lacO)-gfp (IPTG-inducible) was used as a starting point. All promoters were amplified using PCR and inserted in place of pL(LacO) by Gibson assembly. The corresponding repressors or activators, which can interact with small molecule inducers, were inserted into the Escherichia coli genome or cloned onto the same plasmid that harbors the promoter-gfp output module. For example, the proteins PhlF and LacI repressed DAPG- and IPTG-inducible promoters, respectively. PhlF was inserted in a plasmid under regulation of proD promoter, whereas the LacI repressor was already present in the genome of DH5αPRO. Similarly, the AHL-inducible transcriptional activator, LuxR, was constitutively expressed from a plasmid and can activate promoter pLuxR on binding to AHL. The regulatory components necessary for Rham induction were already present in the E. coli genome and did not required additional engineering. To construct the AHL sender plasmid, LuxI was put onto a plasmid under the regulation of aTc-inducible promoter PLtetO. Finally, all ligations for plasmid construction were transformed into E. coli strain DH5αPRO with standard protocols and are described in Fig. S6.

Cell Induction in the Living Device.

The cell-contained device was immersed in LB broth with carbenicillin and inducer(s) at 25 °C as mentioned in the text. Inducers could be added in LB at final concentrations of 100 μM DAPG, 100 nM AHL, 1 mM IPTG, 12 mM Rham, and/or 200 ng/mL aTc. Alternatively, a piece of sterilized tissue paper (Kimtech) was dipped in LB with inducer in it and put on top of the hydrogel layer. The device and the tissue paper were kept at 25 °C and relative humidity of 90%. The latter method was not only applicable for the cell to receive inducers from the environment (e.g., induction of IPTGRCV/GFP by IPTG) but also, more suitable for intercellular communication when dilution of signaling molecules by the environment was undesirable. Every induction/detection experiment was performed and repeated at least three times.

Cell Viability Assay.

By using the LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability and Counting Kit in combination with flow cytometry, the cell viability assay was conducted for cells retrieved from devices and live/dead controls. The fluorescent LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability and Counting Kit consists of two stains: the green fluorescent nucleic acid stain SYTO 9, which stains the nucleic acids of both living and dead bacteria, and the red fluorescent nucleic acid stain propidium iodide, which only stains bacteria that have damaged and leaky membranes. RhamRCV/GFP bacterial suspensions were retrieved from the device by poking a hole from the hydrogel using metal needles after 12, 24, 48, and 72 h of culturing. Live-cell controls (untreated) and dead-cell controls (isopropyl alcohol-treated) were set as standards. A diluted bacterial suspension and the LIVE/DEAD BacLight solution were mixed together and incubated at room temperature protected from light for 15 min. The stained cell samples were then analyzed by an LSRFortessa Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences). For each sample, at least 104 events were recorded using a flow rate of 0.5 µL/s. FlowJo (TreeStar) was used to analyze the data. All events were gated by forward scatter and side scatter. In Fig. S2, green fluorescence denotes both live and dead bacteria, and the red fluorescence denotes bacteria that have been damaged and leaky membranes. The distributions of the live and dead populations were distinguished in the cytograms.

Cell Escape Test.

An intact hydrogel–elastomer living device, and a defective living device (with weak hydrogel–elastomer bonding) were tested for comparison. Also, the agar hydrogel with the same dimensions as the hydrogel–elastomer hybrid and encapsulating RhamRCV/GFP bacteria was used as a control. We first deformed the living materials, which contained RhamRCV/GFP bacteria in different modes (i.e., twisting and stretching), and then, immersed them in LB for 24 h. To test the bacteria leakage, LB solutions surrounding the device were collected for streaking on LB agar plates after 24 h, and OD600 measurements by UV-Visible Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) were taken after 6, 12, 20, and 24 h.

In addition, we prepared agar hydrogel with bacteria encapsulated: 1.5% (wt/vol) agar was dissolved in water at 90 °C. When the agar solution cooled down to ∼40 °C, the RhamRCV/GFP bacteria was mixed with the solution. As it continued to cool down, the solution could solidify and became a gel.

GFP Expression Assay.

For quantitative measurement of GFP expression, the bacteria were isolated from the device by 32-gauge needles and diluted to 107 cells per 1 mL. Single-cell fluorescence was measured using an LSRFortessa Flow Cytometer with a 488-nm laser for GFP. For each sample, at least 104 events were recorded using a flow rate of 0.5 µL/s. FlowJo was used to analyze the data. All events were gated by forward scatter and side scatter. Integration of cell numbers over fluorescence was calculated and normalized to the maximum fluorescence. For qualitative observation of GFP expression by the naked eye, the living devices were exposed to benchtop UltraSlim Blue Light Transilluminators (New England Biogroup; wavelength of 470 nm). We extracted the green channel from optical images and adjusted the exposure by setting gamma correction to 0.2 in Adobe Photoshop CS6 (Adobe). Microscopic observation was done by the aid of a fluorescent microscope (Nikon Eclipse LV100ND), and all imaging conditions, such as beam power and exposure time, were maintained the same across different samples.

Preparation and Testing of Sensor Patch on Skin.

The robust hybrid patches with wavy microchannels were fabricated by using hydrogel (PAAm-alginate) and silicone elastomer (Sylgard 184) following the previously described method. Bacterial suspension of RhamRCV/GFP was infused to the upper two channels of the patch, and AHLRCV/GFP was infused to the lower two channels of the patch. Before we adhered the living patch on forearm, the skin was smeared with LB of 12 mM Rham and/or 100 nM AHL. Note that these two inducers are nontoxic and safe to be applied on skin. The living patch was conformably mounted on the skin with the PDMS layer exposed to air and fixed on the skin by a clear Scotch tape. To show the antidehydration property of the wearable living patch, a pure hydrogel device without elastomer layer was fabricated by assembling micropatterned hydrogel and flat hydrogel sheet. To compare dehydration of hydrogel–elastomer hybrids and the hydrogel device without the elastomer layer, these two types of devices were conformably attached to curved surfaces of plastic beakers. The dehydration tests were carried out at room temperature with low humidity (25 °C and 50% relative humidity) for 24 h. To show the stretchability of living patch, we also fabricated the living skin patch with Ecoflex instead of PDMS in the same design and dimension. As illustrated in Fig. S3, the stretchable skin patch with induced bacteria can be stretched and relaxed to 1.8 times its original length without failure.

Preparation and Testing of Living Chemical Detectors on Nitrile Glove Fingertips.

To show the living chemical sensors at the nitrile glove fingertips, hydrogel–elastomeric glove hybrids with spiral microchannels were prepared. We first laminated thin hydrogel sheets with patterned cell chambers on the fingertips of nitrile gloves and then, encapsulated different inducible cell inside. Different strains of bacteria (IPTGRCV/GFP, AHLRCV/GFP, and RhamRCV/GFP) were injected into spiral-shaped cell chambers at different fingertips. To test the functionality of the fingertip sensor array, we used a cluster of cotton balls soaked in LB with 1 mM IPTG and 12 mM Rham. The glove was worn to grab the wet cotton balls, and hydrogels at the fingertips contacted the inducer-containing cotton balls. The fluorescence at the fingertips was exampled after 4 h of contact with the cotton balls using the benchtop transilluminator.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by Office of Naval Research (ONR) Grants N00014-14-1-0528 and N00014-13-1-0424, National Science Foundation (NSF) Grants CMMI-1253495 and MCB-1350625, and National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant P50GM098792. H.Y. acknowledges financial support from a Samsung Scholarship. X.Z. acknowledges support from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Lincoln Laboratory.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1618307114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pardee K, et al. Paper-based synthetic gene networks. Cell. 2014;159(4):940–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mimee M, Tucker AC, Voigt CA, Lu TK. Programming a human commensal bacterium, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, to sense and respond to stimuli in the murine gut microbiota. Cell Syst. 2015;1(1):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friedland AE, et al. Synthetic gene networks that count. Science. 2009;324(5931):1199–1202. doi: 10.1126/science.1172005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siuti P, Yazbek J, Lu TK. Engineering genetic circuits that compute and remember. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(6):1292–1300. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2014.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen AY, et al. Synthesis and patterning of tunable multiscale materials with engineered cells. Nat Mater. 2014;13(5):515–523. doi: 10.1038/nmat3912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Florea M, et al. Engineering control of bacterial cellulose production using a genetic toolkit and a new cellulose-producing strain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(24):E3431–E3440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522985113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng AA, Lu TK. Synthetic biology: An emerging engineering discipline. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2012;14:155–178. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-071811-150118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feinberg AW, et al. Muscular thin films for building actuators and powering devices. Science. 2007;317(5843):1366–1370. doi: 10.1126/science.1146885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nawroth JC, et al. A tissue-engineered jellyfish with biomimetic propulsion. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(8):792–797. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerber LC, Koehler FM, Grass RN, Stark WJ. Incorporation of penicillin-producing fungi into living materials to provide chemically active and antibiotic-releasing surfaces. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51(45):11293–11296. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee KY, Mooney DJ. Hydrogels for tissue engineering. Chem Rev. 2001;101(7):1869–1879. doi: 10.1021/cr000108x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao X, et al. Active scaffolds for on-demand drug and cell delivery. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(1):67–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007862108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seliktar D. Designing cell-compatible hydrogels for biomedical applications. Science. 2012;336(6085):1124–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.1214804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao X. Multi-scale multi-mechanism design of tough hydrogels: Building dissipation into stretchy networks. Soft Matter. 2014;10(5):672–687. doi: 10.1039/C3SM52272E. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuk H, Zhang T, Parada GA, Liu X, Zhao X. Skin-inspired hydrogel-elastomer hybrids with robust interfaces and functional microstructures. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12028. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong JP, Katsuyama Y, Kurokawa T, Osada Y. Double‐network hydrogels with extremely high mechanical strength. Adv Mater. 2003;15(14):1155–1158. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun J-Y, et al. Highly stretchable and tough hydrogels. Nature. 2012;489(7414):133–136. doi: 10.1038/nature11409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuk H, Zhang T, Lin S, Parada GA, Zhao X. Tough bonding of hydrogels to diverse non-porous surfaces. Nat Mater. 2016;15(2):190–196. doi: 10.1038/nmat4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin S, et al. Design of stiff, tough and stretchy hydrogel composites via nanoscale hybrid crosslinking and macroscale fiber reinforcement. Soft Matter. 2014;10(38):7519–7527. doi: 10.1039/c4sm01039f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee JN, Jiang X, Ryan D, Whitesides GM. Compatibility of mammalian cells on surfaces of poly(dimethylsiloxane) Langmuir. 2004;20(26):11684–11691. doi: 10.1021/la048562+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Darnell MC, et al. Performance and biocompatibility of extremely tough alginate/polyacrylamide hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2013;34(33):8042–8048. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.06.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robb WL. Thin silicone membranes--their permeation properties and some applications. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1968;146(1):119–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1968.tb20277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huh D, et al. Reconstituting organ-level lung functions on a chip. Science. 2010;328(5986):1662–1668. doi: 10.1126/science.1188302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halldorsson S, Lucumi E, Gómez-Sjöberg R, Fleming RMT. Advantages and challenges of microfluidic cell culture in polydimethylsiloxane devices. Biosens Bioelectron. 2015;63:218–231. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2014.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang K-I, et al. Rugged and breathable forms of stretchable electronics with adherent composite substrates for transcutaneous monitoring. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4779. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuk H, et al. Hydraulic hydrogel actuators and robots optically and sonically camouflaged in water. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14230. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao IC, Moutos FT, Estes BT, Zhao X, Guilak F. Composite three-dimensional woven scaffolds with interpenetrating network hydrogels to create functional synthetic articular cartilage. Adv Funct Mater. 2013;23(47):5833–5839. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201300483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dilanji GE, Langebrake JB, De Leenheer P, Hagen SJ. Quorum activation at a distance: Spatiotemporal patterns of gene regulation from diffusion of an autoinducer signal. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134(12):5618–5626. doi: 10.1021/ja211593q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin S, et al. Stretchable hydrogel electronics and devices. Adv Mater. 2016;28(22):4497–4505. doi: 10.1002/adma.201504152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leveau JH, Lindow SE. Predictive and interpretive simulation of green fluorescent protein expression in reporter bacteria. J Bacteriol. 2001;183(23):6752–6762. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.23.6752-6762.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alon U. An Introduction to Systems Biology: Design Principles of Biological Circuits. CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuhlman T, Zhang Z, Saier MH, Jr, Hwa T. Combinatorial transcriptional control of the lactose operon of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(14):6043–6048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606717104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischer H, List E, Koh R, Imberger J, Brooks N. Mixing in Inland and Coastal Waters. Academic; New York: 1979. pp. 229–242. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cubitt AB, et al. Understanding, improving and using green fluorescent proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20(11):448–455. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Belkin S. Microbial whole-cell sensing systems of environmental pollutants. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6(3):206–212. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(03)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]