Significance

Patients with early infantile epileptic encephalopathy experience severe seizures and cognitive impairment and are at increased risk for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). Here, we investigated the neuronal phenotype of a mouse model of early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE) 13 caused by a mutation in the sodium channel gene SCN8A. We found that excitatory and inhibitory neurons from mutant mice had increased persistent sodium current density. Measurement of action potential firing in brain slices from mutant mice revealed hyperexcitability with spontaneous firing in a subset of neurons. These changes in neurons are predicted to contribute to the observed seizure phenotype in whole animals. Our results provide insights into the disease mechanism and future treatment of patients with EIEE13.

Keywords: sodium channel, epilepsy, mouse model, action potential, Na/Ca exchange

Abstract

Patients with early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE) experience severe seizures and cognitive impairment and are at increased risk for sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). EIEE13 [Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) # 614558] is caused by de novo missense mutations in the voltage-gated sodium channel gene SCN8A. Here, we investigated the neuronal phenotype of a mouse model expressing the gain-of-function SCN8A patient mutation, p.Asn1768Asp (Nav1.6-N1768D). Our results revealed regional and neuronal subtype specificity in the effects of the N1768D mutation. Acutely dissociated hippocampal neurons from Scn8aN1768D/+ mice showed increases in persistent sodium current (INa) density in CA1 pyramidal but not bipolar neurons. In CA3, INa,P was increased in both bipolar and pyramidal neurons. Measurement of action potential (AP) firing in Scn8aN1768D/+ pyramidal neurons in brain slices revealed early afterdepolarization (EAD)-like AP waveforms in CA1 but not in CA3 hippocampal or layer II/III neocortical neurons. The maximum spike frequency evoked by depolarizing current injections in Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1, but not CA3 or neocortical, pyramidal cells was significantly reduced compared with WT. Spontaneous firing was observed in subsets of neurons in CA1 and CA3, but not in the neocortex. The EAD-like waveforms of Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 hippocampal neurons were blocked by tetrodotoxin, riluzole, and SN-6, implicating elevated persistent INa and reverse mode Na/Ca exchange in the mechanism of hyperexcitability. Our results demonstrate that Scn8a plays a vital role in neuronal excitability and provide insight into the mechanism and future treatment of epileptogenesis in EIEE13.

The voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) Nav1.6, encoded by SCN8A, is broadly expressed in mammalian brain (1). In the axon initial segment of neurons, Nav1.6 regulates action potential (AP) initiation, and at nodes of Ranvier, it contributes to saltatory conduction. Scn8a deletion in mice results in paralysis due to failure of neuromuscular transmission, whereas partial loss-of-function mutations result in gait disorders such as ataxia and dystonia (2, 3). The activity of both excitatory and inhibitory neurons is reduced in mutant mice lacking Nav1.6, and repetitive firing of cerebellar Purkinje cells and other repetitively firing neurons is impaired (1, 4–7). De novo mutations of SCN8A have been identified as an important cause of early infantile epileptic encephalopathy (EIEE) (8, 9). Epileptic encephalopathy resulting from mutation of SCN8A is designated EIEE13 [Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) # 614558]. The first reported mutation, p.Asn1768Asp, was identified in a proband with onset of convulsive seizures at 6 mo of age (10). Comorbidities included intellectual disability, ataxia, and sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP) at 15 y of age. Since then, more than 150 patients with de novo SCN8A mutations have been identified (8, 11) (www.scn8a.net/Home.aspx). Four large screens of individuals with epileptic encephalopathy detected de novo mutations of SCN8A in ∼1% of patients (13/1,557) (12–15). The common features of EIEE13 include seizure onset between birth and 18 mo of age, mild to severe cognitive and developmental delay, and mild to severe movement disorders (11, 13). Approximately 50% of patients are nonambulatory and 12% of published cases (5/43) experienced SUDEP during childhood or adolescence (10, 13, 16, 17).

Almost all of the identified mutations in SCN8A are missense mutations. Ten of these mutations have been tested functionally in transfected cells, and eight were found to introduce changes in the biophysical properties of Nav1.6 that are predicted to result in neuronal hyperexcitability, including elevated persistent sodium current (INa,P), hyperpolarizing shifts in the voltage dependence of activation, and impaired current inactivation (10, 16, 18–21). It is important to confirm these observations in multiple classes of neurons expressing the mutation at a constitutive level, because different types of neurons respond differently to mutations of Scn8a (1) and effects in brain may differ from those in transfected cells (e.g., ref. 22).

To investigate the pathogenic effects of SCN8A mutations in vivo, we generated a knock-in mouse carrying the first reported patient mutation, p.Asn1768Asp (N1768D) (23). In a transfected neuronal cell line, this mutation generated elevated INa,P and increased excitability (10). Heterozygous Scn8aN1768D/+ mice recapitulate the seizures, ataxia, and sudden death of the heterozygous proband, with seizure onset at 2–4 mo of age and sudden death within 3 d (24, 25). We report that Scn8aN1768D/+ mouse excitatory and inhibitory hippocampal neurons have region-specific increases in INa,P density with altered AP waveforms. Our data confirm the critical role of Scn8a in neuronal excitability and provide insight into the mechanism of EIEE13.

Results

Persistent INa Is Increased in Scn8aN1768D/+ Hippocampal Neurons.

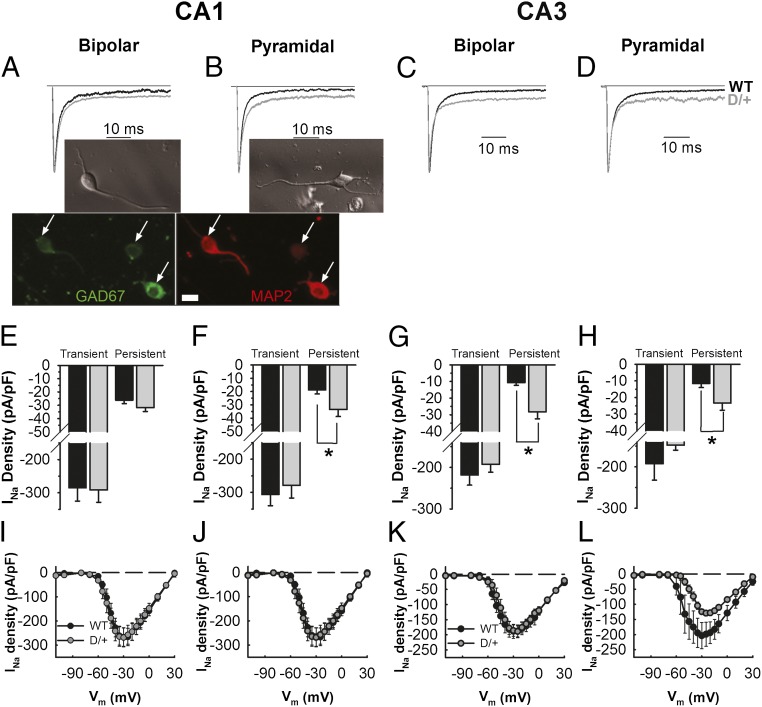

CA1 and CA3 hippocampal neuron INa exhibited two components, a large, fast transient current and a small INa,P (Fig. 1 A–D). We compared INa,P density between WT and Scn8aN1768D/+ neurons with bipolar and pyramidal morphologies from both hippocampal regions. Representative images of bipolar and pyramidal neurons are shown in Fig. 1A and B, respectively. Neurons with bipolar morphology stain positively for MAP2 (red; Fig. 1A), GAD-67 (green; Fig. 1A and Fig. S1), and GABA (magenta; Fig. S1), confirming their identity as inhibitory neurons. In the Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 region, pyramidal but not bipolar neuron INa,P was increased approximately twofold over WT, with no change in transient INa in either population (Fig. 1 A, B, E, F, I, and J). In the Scn8aN1768D/+ CA3 region, INa,P was increased greater than twofold over WT in both bipolar and pyramidal neurons (Fig. 1 C, D, G, H, K, and L). For CA1 bipolar and pyramidal neurons and for CA3 bipolar neurons, the peak of the transient INa, measured through the entire voltage range, was not different between genotypes (Fig. 1 E–G and I–K). For CA3 pyramidal neurons, the peak transient INa appeared to be reduced in Scn8aN1768D/+ neurons compared with WT, but because P = 0.05, the data did not meet the criterion for significance (Fig. 1 H and L).

Fig. 1.

Changes in transient and INa,P density in Scn8aN1768D/+ neurons. (A–D) Normalized, representative INa traces in CA1 or CA3 bipolar or pyramidal neurons from WT (black) or Scn8aN1768D/+ (gray) mutant mice. (Insets) (A) Representative bright field image of a bipolar neuron (Upper); immunostaining showing MAP2-positive neurons with bipolar morphology are GAD67 positive (Lower). (Scale bar: 10 µm.) (B) Representative bright field image of a pyramidal neuron. (E) Average transient and persistent INa densities for CA1 bipolar neurons from WT (black, n = 11, N = 5) or Scn8aN1768D/+ (gray, n = 12, N = 8). (F) Average transient and INa,P densities for CA1 pyramidal neurons isolated from WT (black, n = 11, N = 5) or Scn8aN1768D/+ (gray, n = 10, N = 7). (G) Average transient and INa,P density for CA3 bipolar neurons from WT (black, n = 12, N = 9) or Scn8aN1768D/+ (gray, n = 11, N = 5). (H) Average transient and INa,P densities for CA3 pyramidal neurons isolated from WT (black, n = 9, N = 6) or Scn8aN1768D/+ (gray, n = 10, N = 8). (I) Averaged current–voltage relationships for CA1 bipolar neurons isolated from WT (n = 11, N = 5) or Scn8aN1768D/+ (n = 11, N = 8). (J) Similar to I but for CA1 pyramidal neurons from WT (n = 11, N = 4) or Scn8aN1768D/+ (n = 9, N = 7). (K) Averaged current–voltage relationships for CA3 bipolar neurons isolated from WT (n = 10, N = 9) or Scn8aN1768D/+ (n = 9, N = 5). (L) Similar to E but for CA3 pyramidal neurons from WT (n = 8, N = 5) or Scn8aN1768D/+ (n = 8, N = 6). N, number of animals; n, number of cells. Error bars indicate SEM. *P < 0.05.

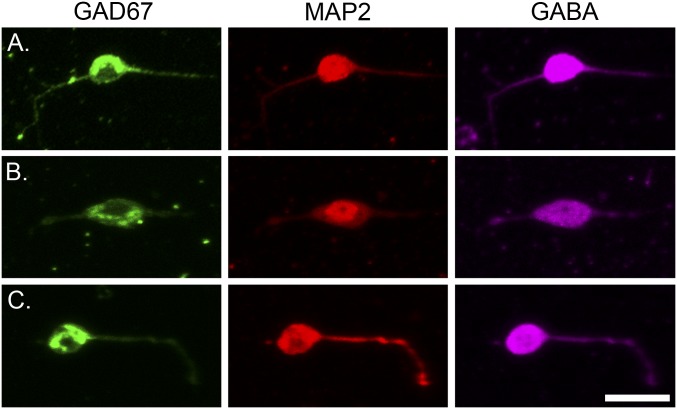

Fig. S1.

Immunostaining of acutely isolated mouse hippocampal neurons. Immunostaining of acutely isolated mouse hippocampal neurons showing that neurons with bipolar morphology are positive for: (Left) GAD67 (green). (Center) MAP2 (red). (Right) GABA (magenta). A, B, and C show three different examples of isolated bipolar neurons positive for all three markers. (Scale bar: 20 μm.)

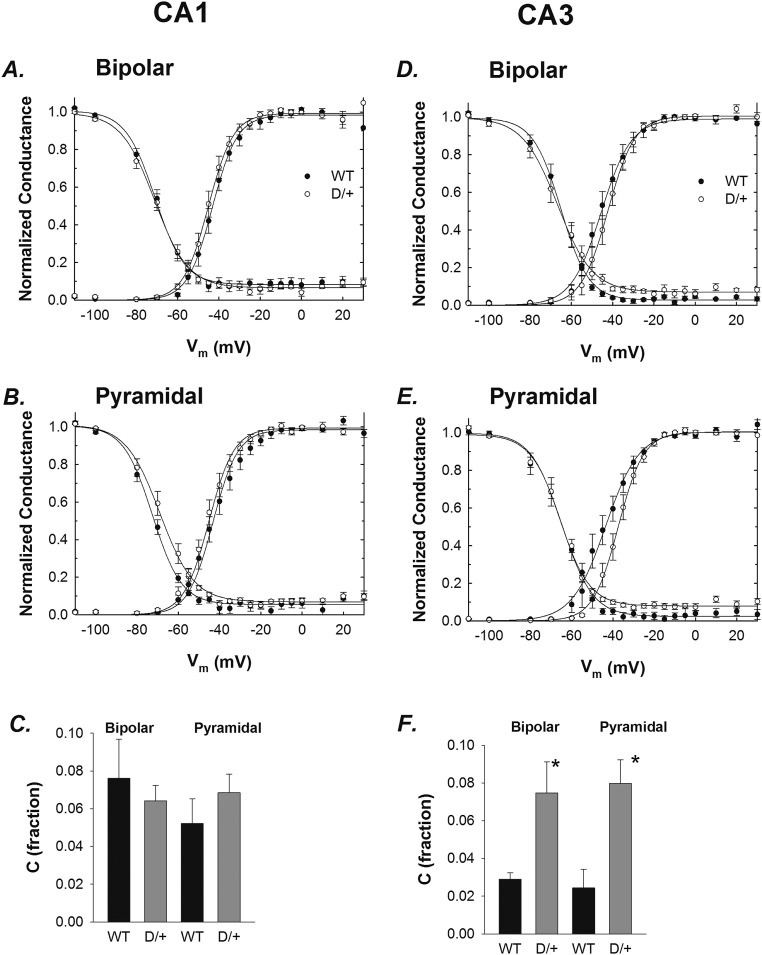

Current–voltage relationships were transformed to conductance to determine activation properties. For CA1 bipolar and pyramidal neurons, no differences in activation or inactivation were found between genotypes (Fig. S2 A and B and Table S1). In contrast, for CA3 pyramidal neurons (Fig. S2E and Table S1), we observed a decrease in the activation slope (k), suggesting that mutant neurons have reduced sensitivity to changes in membrane potential. No differences were observed between genotypes for CA3 bipolar neurons (Fig. S2D and Table S1). For the voltage dependence of inactivation, all parameters of the Boltzmann equation were similar between groups for CA3 bipolar and pyramidal neurons with the exception of the constant used to estimate INa,P (Fig. S2 E and F). We found a greater than twofold increase in INa,P in Scn8aN1768D/+ CA3 neurons of both types, compared with WT (Fig. S2F and Table S1).

Fig. S2.

Voltage-dependent properties of WT and Scn8aN1768D/+ neurons. (A and B) Activation and inactivation curves for the CA1 bipolar and pyramidal neurons shown in Fig. 1 I and J. (D and E) Activation and inactivation curves for the CA3 bipolar and pyramidal neurons shown in Fig. 1 K and L. (C and F) Fraction of INa,P calculated from inactivation curves for CA1 and CA3, respectively. *P < 0.05. Error bars indicate SEM.

Table S1.

Voltage-dependent properties of WT and mutant hippocampal neurons

| CA1 | CA3 | |||||||

| WT | N1768D/+ | WT | N1768D/+ | |||||

| Bipolar | Pyramidal | Bipolar | Pyramidal | Bipolar | Pyramidal | Bipolar | Pyramidal | |

| n/N | 11/5 | 11/4 | 11/8 | 9/7 | 10/9 | 8/5 | 9/5 | 8/6 |

| Activation | ||||||||

| Gmax, nS | 5.03 ± 0.60 | 6.37 ± 1.08 | 5.02 ± 0.83 | 4.94 ± 0.66 | 3.34 ± 0.45 | 3.49 ± 0.57 | 3.24 ± 0.30 | 2.58 ± 0.10 |

| k, mV | 5.71 ± 0.73 | 6.94 ± 0.56 | 5.48 ± 0.46 | 6.76 ± 0.85 | 6.17 ± 0.62 | 6.72 ± 0.59 | 5.79 ± 0.60 | 5.35 ± 0.17* |

| V1/2, mV | −42.48 ± 1.83 | −42.52 ± 2.24 | −44.76 ± 1.61 | −45.40 ± 1.60 | −45.00 ± 2.29 | −43.62 ± 2.32 | −42.77 ± 1.91 | −37.62 ± 1.72 |

| Inactivation | ||||||||

| k, mV | −6.90 ± 0.45 | −6.97 ± 0.38 | −7.69 ± 0.41 | −7.31 ± 0.26 | −6.10 ± 0.44 | −6.87 ± 0.58 | −7.26 ± 0.53 | −6.83 ± 0.32 |

| V1/2, mV | −70.94 ± 1.58 | −72.80 ± 1.28 | −71.55 ± 1.69 | −68.93 ± 2.46 | −65.50 ± 2.05 | −65.32 ± 2.58 | −68.68 ± 3.50 | −66.03 ± 1.58 |

| C (fraction) | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.06 ± 8.1e-3 | 0.07 ± 9.7e-3 | 0.03 ± 3.6e-3 | 0.02 ± 9.9e-3 | 0.07 ± 0.02* | 0.08 ± 0.01* |

N, number of animals; n, number of cells. *P < 0.05 compared with WT.

Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 Hippocampal Neurons in Acute Brain Slices Exhibit Early Afterdepolarization (EAD)-Like Responses and Spontaneous Firing.

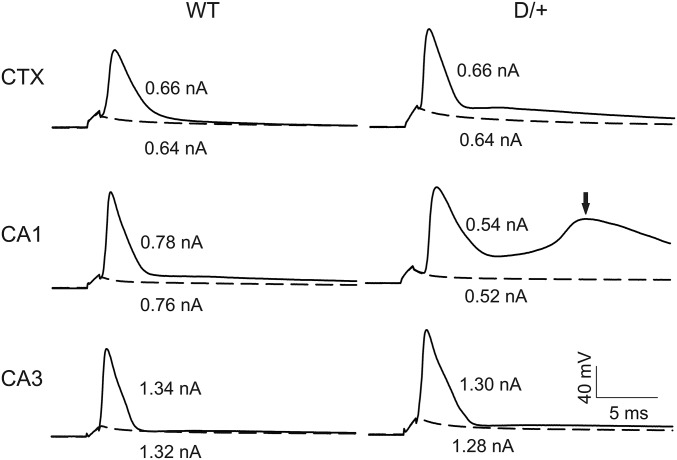

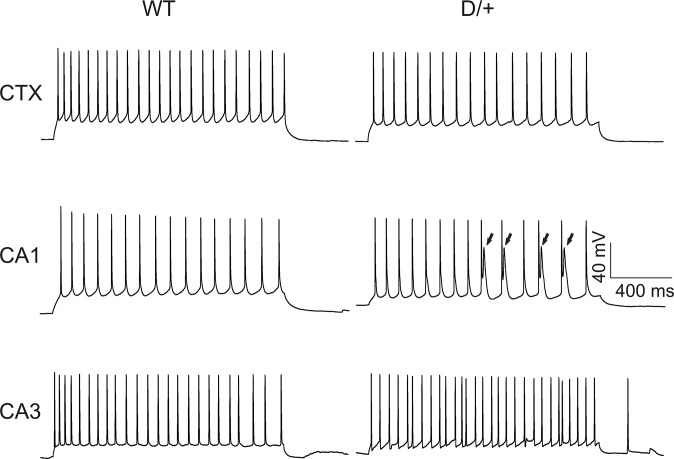

We next examined passive and active membrane properties of neurons in acute brain slices prepared from the same mice used for the isolated neuron preparations. To determine whether effects of the mutation were brain region specific, we recorded from the CA1, CA3, and neocortical layer II/III. Fig. 2 shows representative APs evoked by threshold current injections in CA1, CA3, and neocortical layer II/III pyramidal cells in WT and Scn8aN1768D/+ brain slices. Scn8aN1768D/+ neocortical and CA3 neurons showed no changes in neuronal resting membrane potential, input resistance, threshold potential, or peak amplitude of APs compared with WT (Table S2). For CA1, all values were similar for WT and mutant with the exception of input resistance, which was reduced in mutant neurons (Table S2). We observed early after-depolarization (EAD)-like events in the late decay phases of the AP waveform in Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1, but not in CA3 or neocortical, pyramidal neurons (Fig. 2, arrow), which resulted in increases in the decay tau (Table S3). Consistent with this result, there were differences between genotypes in AP duration (APD) in CA1, measured at points of 50% (APD50) or 80% (APD80) repolarization from the AP peak, and increased area under the AP waveform (Table S3). We observed EAD-like waveforms in CA1 pyramidal neurons in slices prepared from 17 of 25 Scn8aN1768D/+ mice (24 of 31 cells examined) but in none of 14 WT mice (16 cells examined). CA3 and neocortical pyramidal neurons showed no differences in AP rise or decay rate or AP duration between genotypes (Table S3). These results suggest brain region and circuit level specificity of the Scn8aN1768D/+ phenotype.

Fig. 2.

Scn8aN1768D/+ hippocampal CA1 neurons exhibit EAD-like responses. Representative APs from neocortical layer II/III (CTX), CA1, or CA3 pyramidal cells from WT or Scn8aN1768D/+ (D/+) mice. APs were evoked by injection of threshold currents while cells were held at RMP. Dotted lines indicate responses evoked by subthreshold stimulation. The arrow in Middle Right indicates an EAD-like event in the AP generated in a mutant pyramidal cell. Each trace is a representative example from WT (n = 9, 14, and 6 mice, respectively, for CTX, CA1, and CA3) and Scn8aN1768D/+ (D/+) (n = 6, 25, and 6 mice, respectively, for CTX, CA1, and CA3).

Table S2.

Comparison of passive and evoked membrane electrical properties of neocortical layer II/III, hippocampal CA1, and CA3 pyramidal cells in brain slices from WT and Scn8aN1768D/+ mice

| Brain region | Genotype | Resting Vm, mV | Input resistance, MΩ | VThreshold, mV | Peak amplitude, mV |

| CTX | WT | −68.0 ± 3.0 (9/9) | 454 ± 57 (9/9) | −46.2 ± 1.4 (9/9) | 107 ± 5.0 (9/9) |

| D/+ | −64.0 ± 3.7 (7/7) | 526 ± 82 (7/7) | −46.0 ± 2.9 (7/7) | 98.8 ± 5.5 (7/7) | |

| CA1 | WT | −62.3 ± 2.2 (16/14) | 363 ± 48 (16/14) | −46.3 ± 1.6 (16/14) | 95.5 ± 3.7 (16/14) |

| D/+ | −59.4 ± 1.2 (33/25) | 277 ± 33* (33/25) | −48.1 ± 1.0 (33/25) | 102 ± 2.7 (33/25) | |

| CA3 | WT | −60.8 ± 2.3 (6/6) | 321 ± 21 (6/6) | −49.6 ± 1.8 (6/6) | 107 ± 4.3 (6/6) |

| D/+ | −60.1 ± 3.4 (7/7) | 377 ± 89 (7/7) | −47.3 ± 3.1 (7/7) | 101 ± 7.7 (7/7) |

Values are mean ± SEM (no. of cells/no. of mice). CA1, hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cells; CA3, hippocampal CA3 pyramidal cells; CTX, neocortical layer II/III pyramidal cells; peak amplitude, peak amplitude of APs measured from the resting membrane potential level to the peak; resting Vm, resting membrane potential; VThreshold, threshold membrane potential required for evoking an AP; . *P < 0.005 compared with WT, one-way ANOVA, post hoc test used Dunn’s method.

Table S3.

Scn8aN1768D/+ hippocampal CA1 neurons have increased AP duration

| Genotype | Rise Tau, ms | Decay Tau, ms | APD50, ms | APD80, ms | Area under AP, mV⋅ms |

| WT | 0.6 ± 0.1 (14/14) | 1.5 ± 0.1 (14/14) | 1.9 ± 0.1 (14/14) | 2.9 ± 0.1 (14/14) | 2.9 ± 0.1 (14/14) |

| D/+ | 0.8 ± 0.1 (27/25) | 2.7 ± 0.4** (27/25) | 2.5 ± 0.1** (27/25) | 5.2 ± 0.6*** (27/25) | 2.9 ± 0.1** (27/25) |

Values are mean ± SEM (no. of cells/no. of mice). APD50, AP duration at 50% repolarization from the peak (milliseconds); APD80, APD at 80% of repolarization from the peak (∼20% of the peak AP amplitude) (milliseconds); Area, area under the AP waveform from initiation to repolarization at 15 ms. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Mann–Whitney Rank Sum test.

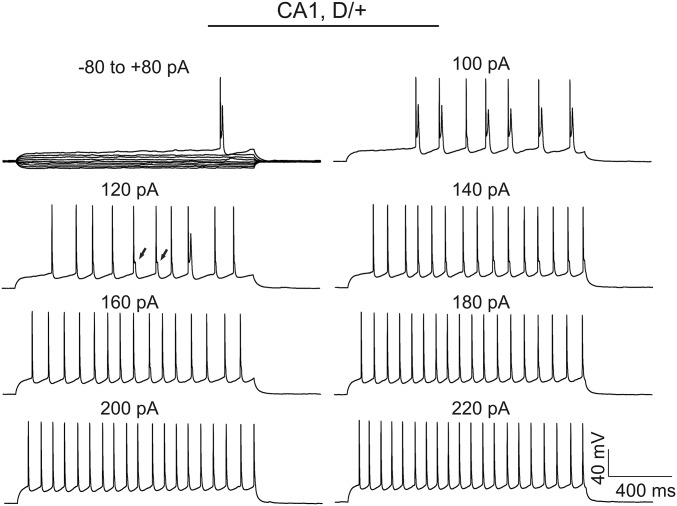

We compared the AP firing patterns of neocortical layer II/III, CA1, and CA3 pyramidal cells in WT and Scn8aN1768D/+ brain slices (Fig. 3). Repetitive AP firing was evoked by injection of 1,500 ms currents varying from −80 pA to 220 pA at the resting membrane potential (RMP) of each cell. Representative traces of repetitive AP firing evoked by injection of 60 pA of current in WT or Scn8aN1768D/+ neocortical, CA1, or CA3 pyramidal cells are shown in Fig. 3. We observed no differences in AP firing pattern or maximum firing frequency in neocortical or CA3 pyramidal neurons between genotypes (Table S2). In contrast, Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 neurons showed EAD-like events in response to long-pulse current injections (Fig. 3, arrows). None of the neocortical or CA3 pyramidal cells demonstrated a similar response. EAD-like responses evoked by long pulses of current in CA1 were observed only in the low intensity range of depolarizing current injections (<160 pA). Stronger current injections resulted in the disappearance of EAD-like events (Fig. S3), suggesting a membrane potential-dependent response that may involve INa inactivation. In most EAD-like events, a single spike was superimposed on the AP waveform (e.g., Fig. 3, arrows). Because of the slower and broadened late decay phase of the AP in mutant CA1 neurons (Fig. 3 and Fig. S3), the spike frequency was reduced compared with WT.

Fig. 3.

Evoked firing patterns and maximal AP firing frequencies in Scn8aN1768D/+ and WT cortical and hippocampal neurons. Representative traces showing evoked repetitive firing of neocortical layer II/III (CTX), CA1, or CA3 pyramidal neurons from WT or Scn8aN1768D/+ (D/+) mice. Repetitive AP firing was evoked by injections of 1,500-ms pulse currents of −80 pA to +220 pA (60 pA-evoked responses are shown). EADs (arrows) were observed in 17 of 25 Scn8aN1768D/+ mice (19 of 31 cells) tested, whereas CA1 pyramidal cells from 0 of 14 WT mice (16 cells) tested displayed this response. Each trace is a representative example of WT (n = 9, 16, and 6 cells, respectively, for CTX, CA1, and CA3) and Scn8aN1768D/+ (D/+) (n = 7, 25, and 7 cells, respectively, for CTX, CA1, and CA3) mice.

Fig. S3.

EAD-like responses in Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 pyramidal cells are stimulation intensity-dependent. Representative EAD-like response in a Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 neuron was evoked by a long pulse of current injection with intensity varying from −80 pA to 220 pA. Note the apparent widening in the late phase of AP decay (e.g., arrows in the 120 pA panel). Each trace is representative of recordings from 17 Scn8aN1768D/+ mice (24 of 31 cells examined).

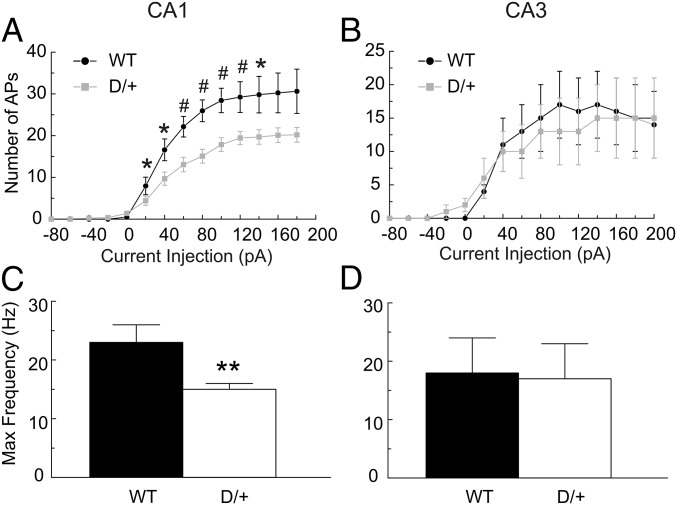

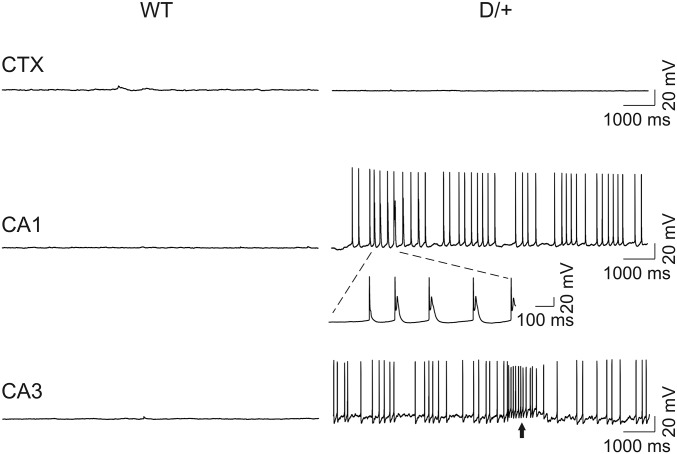

Consistent with the difference in spike frequency, the input/output relationships for CA1 pyramidal cells were different between genotypes (Fig. 4A). The maximum spike frequency evoked by depolarizing current injections in Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 pyramidal cells was reduced compared with WT (Fig. 4 A and C). In contrast, we found no differences in input-output relationships or maximal spike frequency in CA3 (Fig. 4 B and D). Spontaneous firing of CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons was observed in a subset of Scn8aN1768D/+ animals (8 of 27 cells from 8 of 25 mice for CA1 and 4 of 7 cells from 4 of 7 mice for CA3) but was not observed in 16 neurons examined from 14 WT mice (Fig. 5). Of the four mutant CA3 cells that fired spontaneously, three showed bursting activity (e.g., arrow in Fig. 5, Lower). Three of the eight mutant CA1 neurons that fired spontaneously also displayed EAD-like waveforms during spontaneous firing, suggesting intrinsic changes in neuronal excitability.

Fig. 4.

Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 pyramidal cells show stimulation intensity-dependent reduction in AP firing frequency. APs from WT or Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 (A) or CA3 (B) neurons were evoked by injections of 1,500-ms currents varying from −80 pA to 180 pA. Input–output curves show frequency of AP firing vs. stimulation intensity. All values are mean ± SEM of individual recordings from WT (n = 11 and 6 for CA1 and CA3, respectively) and Scn8aN1768D/+ (D/+) (n = 18 and 7, for CA1 and CA3, respectively). (C and D) Comparisons of the maximum firing frequency of CA1 or CA3 pyramidal cells in response to injections of 1,500-ms currents from −80 pA to 220 pA between genotypes. (n = 11 and 6, respectively, for WT CA1 and CA3; n = 18 and 7, respectively, for Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 and CA3 mice).

Fig. 5.

Scn8aN1768D/+ hippocampal neurons fire spontaneously. Spontaneous firing of APs was not observed in WT neocortical (CTX), CA1, or CA3 pyramidal cells held at RMP. A subset of Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 and CA3 pyramidal cells (8 of 20 for CA1 and 4 of 7 for CA3) fired spontaneously at RMP. EAD-like responses (insert with expanded time scale) occurred during spontaneous firing in CA1, but not CA3, pyramidal cells from two of eight Scn8aN1768D/+ mice. Arrow indicates bursting activity. Three of four mutant CA3 cells that fired spontaneously displayed similar bursting activity.

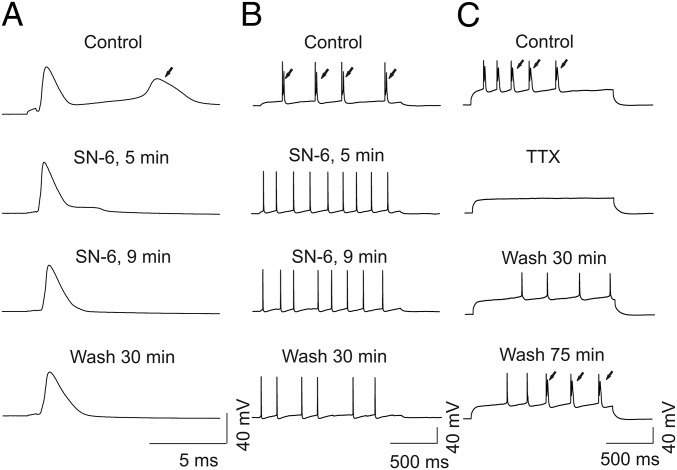

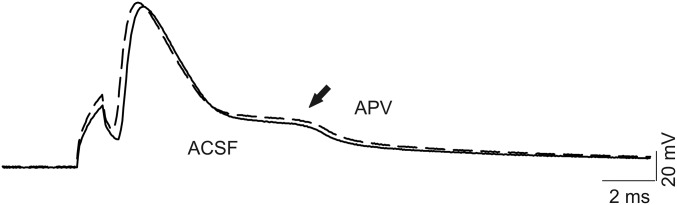

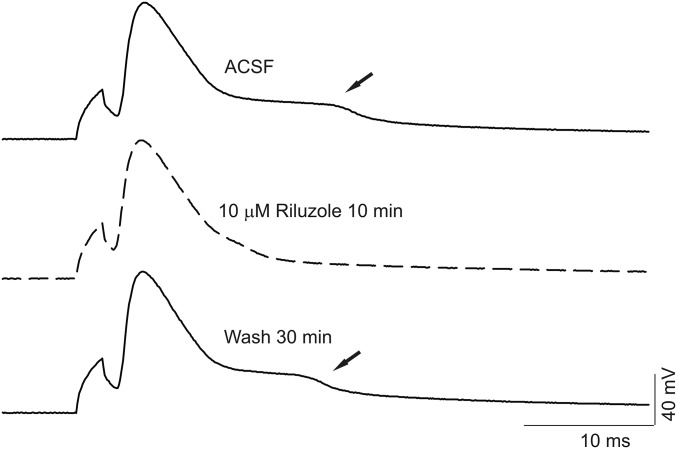

Reverse mode activity of the Na/Ca exchanger (NCX) contributes to the mechanism of hyperexcitability in Scn8aN1768D/+ cardiomyocytes (26). We used SN-6, a reverse mode NCX inhibitor (27), to test for a role for NCX in the EAD-like events observed in Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 pyramidal cells. Application of 10 µM SN-6 blocked the EAD-like waveform in all neurons examined within 5–10 min, although this effect was not reversible (Fig. 6). Treatment of control slices with artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) containing 0.1% DMSO for 30–60 min had no effect on the AP waveform. Treatment with the NMDA receptor antagonist d-(-)-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (APV) failed to block the EAD-like response (Fig. S4). Application of 0.5 µM tetrodotoxin (TTX) reversibly blocked the AP and EAD-like events, with the AP returning before the EAD upon washout of TTX (Fig. 6). Finally, we tested the effects of riluzole, which blocks INa,P (28), on the EAD-like waveform in mutant CA1 pyramidal neurons. Application of 10 μM riluzole rapidly and reversibly suppressed the EAD-like waveforms (Fig. 7).

Fig. 6.

Reverse mode NCX inhibitor SN-6 and TTX suppress EAD-like responses in Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 pyramidal cells. (A and B) Representative recordings showing the effect of 10 µM SN-6 on EAD-like responses in a Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 neuron. EAD evoked by a short (A; 1 ms, pA varying with different suprathreshold stimulation) or long (B; 1,500 ms, 80 pA) pulse of current injection. From top to bottom, time course of effects of 5 µM SN-6 on EAD and reversibility by washout with ACSF for 30 min. Arrows indicate EADs. (C) Representative recordings of APs and EADs before and after application of 0.5 µM TTX for 2 min. From top to bottom, time course of reversibility of APs and EADs following washout with TTX-free ACSF. The APs recovered before the EADs. Traces are representative of recordings in CA1 neurons from four Scn8aN1768D/+ mice.

Fig. S4.

APV does not affect the EAD-like response. Representative AP recording and EAD-like response (arrow) before (solid line) and after (dashed line) application of 100 µM APV for 20 min. Each trace is representative of five recordings from four Scn8aN1768D/+ mice.

Fig. 7.

Riluzole reversibly suppresses EAD-like responses in Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 pyramidal cells. (Top and Middle) Representative AP recordings and EADs (arrows) before (black) and after (dashed) 10 µM riluzole for 10 min. (Bottom) Washing the slice with ACSF for 30 min almost completely recovered the EAD response. Traces are representative of recordings in CA1 neurons from five Scn8aN1768D/+ mice.

Discussion

We used Scn8aN1768D/+ knock-in mice to investigate the mechanism of seizures in SCN8A EIEE. We found increased INa,P density in acutely isolated CA1 pyramidal and CA3 bipolar and pyramidal neurons from mutant Scn8aN1768D/+ mice. Recording from brain slices, we found that the Scn8a mutation did not change neuronal RMP, input resistance, threshold potential, rising phase tau, or peak amplitude of APs in CA3 pyramidal neurons. In contrast, we observed EAD-like events in the late decay phases of the AP waveform in Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 pyramidal neurons, leading to increases in the decay tau, the width of the AP at APD50 and APD80, and the area under the AP. In addition, we observed spontaneous AP firing in a subset of mutant CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons. Application of SN-6, riluzole, or TTX inhibited the EAD-like responses. We propose that Scn8aN1768D/+ hippocampal CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons are hyperexcitable because of increased INa,P conducted by mutant Nav1.6 channels. We also propose that in CA1 pyramidal neurons, increased INa,P results in localized increases in intracellular Na+ to drive reverse mode Na/Ca exchange and alter intracellular Ca2+ handling and the AP waveform, as we have proposed for Scn8aN1768D/+cardiac myocytes (26).

Importantly, INa,P was increased in mutant CA3 inhibitory neurons, predicting that they may also exhibit increased firing rates. Previous work demonstrated that inhibitory hippocampal neurons display progressive synchrony and increased firing rates minutes before the onset of pyramidal neuron hyperexcitability and sustained ictal spiking (29, 30). Thus, increased INa,P in CA3 Scn8aN1768D/+ inhibitory neurons may be critical in the preictal transition to spontaneous seizures in mutant hippocampus. These combined changes in excitability and synchrony in CA3 inhibitory neurons and in CA1 and CA3 pyramidal neurons may underlie seizures in mutant mice and provide new insights into the mechanism of EIEE13 in humans. In our earlier work using patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cell neurons, we proposed that increased transient INa in both pyramidal and bipolar neurons contributes to the mechanism of SCN1A-linked Dravet syndrome (31). Taken together, our work suggests that increased VGSC activity in interneurons and pyramidal neurons may contribute to the mechanism of epileptic encephalopathy.

An unexpected finding was the recording of evoked and spontaneous EAD-like waveforms in CA1 pyramidal neurons in Scn8aN1768D/+ brain slices. EAD-like waveforms are rarely observed in central neurons, although they commonly occur in malfunctioning cardiac myocytes (32), where they have been implicated in the cardiac arrhythmogenic phenotype of a mouse model of Dravet syndrome (33). We showed increased incidence of a related AP waveform, delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs), in ventricular myocytes from Scn8aN1768D/+ mice (26). AP events with some similarity to our results, termed depolarizing afterpotentials (DAPs), have been observed in CA1 pyramidal neurons, but only in the presence of GABA receptor antagonists (34). EAD-like responses in Scn8aN1768D/+ neurons occurred during spontaneous firing or were evoked by pulses of depolarizing current injections in the absence of pharmacological agents. In addition, the time to onset of DAPs in previous studies differed from the EAD-like events described here. DAPs were observed immediately following the AP spike, virtually overlapping the afterhyperpolarization (35). Here, EAD-like responses occurred during the late phases of the AP waveform. Various ionic currents have been implicated in DAPs, depending on brain region (34–38). In rat CA1 pyramidal neurons, DAPs are mediated by NMDA receptor channels (34). Treating brain slices with the NMDA receptor antagonist APV failed to block the EAD-like response (Fig. 7). At calyx of Held terminals, activation of resurgent INa is postulated to be responsible for the generation of DAPs (38). Sodium afterdepolarizations (ADPs) in rat superior colliculus neurons were shown to arise from either persistent or resurgent INa (39). Because of the occurrence of EAD-like responses during the late phase of the AP and the effects of riluzole to block the EAD in Scn8aN1768D/+ CA1 neurons, we propose that these events are the result of increased INa,P. Our data suggest that EAD-like events also involve altered intracellular Ca2+ homeostasis via reverse mode NCX activity. However, in contrast to previously described events mediated primarily by Ca2+ spikes, e.g., in cerebellar inferior olivary neurons (40–42), EAD-like events in Scn8aN1768D/+ neurons are blocked by 0.5 µM TTX, suggesting that they are AP-dependent. Thus, although previously described neuronal ADPs and the EAD-like events observed in this study have different waveforms, both may arise through INa,P.

In contrast to the gain-of-function mutation of Scn8a described here, there is evidence that mutations that decrease Nav1.6 activity are protective against seizures. Scn8a+/− mice are resistant to the initiation and development of kindling, suggesting that Nav1.6 may participate in a self-reinforcing cycle of activity-dependent facilitation in the hippocampus (43). Similarly, the Scn8a mutant med-jo, with a depolarizing shift in the voltage dependence of VGSC activation (44), acts as a genetic modifier of Dravet syndrome by returning seizure threshold to WT levels (45). The Scn8amed-jo allele also rescued the premature lethality of Scn1a+/− Dravet syndrome mice and extended the lifespan of Scn1a−/− mutants (45). Reduction of Scn8a expression by conditional deletion of a floxed allele in hippocampal neurons was protective against picrotoxin-induced seizures (46). Together with the present study, these studies demonstrate that increased Nav1.6 activity can be associated with a predisposition to epilepsy, whereas reduced activity can be protective. Pharmacological reduction of INa,P is being investigated as a potential therapy for epilepsy patients (47).

Increased INa,P has been linked to pathophysiology in multiple tissues. In cardiac myocytes, increased INa,P through Nav1.5 prolongs AP repolarization and serves as a substrate for life-threatening arrhythmias (32). In sensory neurons, enhanced INa,P, conducted through Nav1.8, contributes to pain signaling (48). Mutations of SCN9A, encoding Nav1.7, in patients with paroxysmal extreme pain disorder, result in sensory neuron hyperexcitability by a mechanism that includes increased INa,P (49). In brain, increased INa,P is linked not only to epilepsy, but also to neurodegenerative disease. Increased INa,P conducted through Nav1.6 along demyelinated axons in multiple sclerosis is proposed to lead to activation of reverse Na/Ca exchange, increased intraaxonal Ca2+, and axonal degeneration (50). Astrogliosis has been proposed to occur via a mechanism of increased INa,P, via NaV1.5 (51). In patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, increases in INa,P are associated with shorter survival and riluzole is used as a therapeutic agent (52, 53). Blockers of INa,P have been proposed as novel treatments for metastatic cancer (54). Increased INa,P in strongly metastatic cancer cells has been shown to contribute to abnormal intracellular Ca2+ handling (55). In conclusion, our work adds to the growing body of evidence suggesting that increased INa,P density leads to pathology, in this case, a severe epileptic encephalopathy. Our study demonstrates neuronal hyperexcitability in a mouse model of EIEE13 due to mutation of SCN8A and, thus, offers insight into the mechanism of this devastating pediatric disease. The future development of Nav1.6 selective blockers of INa,P may lead to novel therapeutic treatments for EIEE.

Methods

Detailed methods are provided in SI Methods.

Animals.

All experiments were performed in accordance with NIH guidelines with approval from the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Scn8aN1768D/+ knock-in mice were generated as in refs. 23 and 24.

Preparation of Brain Slices.

Acute brain slices were prepared as in ref. 56.

Acute Hippocampal Neuron Dissociation.

Brain slices were prepared, and the dentate gyrus was removed. The hippocampal region was microdissected and transferred to oxygen saturated HBSS with calcium, magnesium, ascorbic acid, and protease type XIV (Sigma). The tissue was rinsed with cold, oxygen saturated calcium free HBSS, transferred to cold, oxygen saturated, Na-isethionate solution, and triturated by using silicon coated Pasteur pipettes.

INa Recordings in Isolated Hippocampal Neurons.

Voltage clamp recordings were performed as in refs. 31, 57, and 58.

Immunocytochemistry.

Immunocytochemistry was performed as in ref. 59.

Brain Slice Electrophysiology.

Pyramidal cells were visually identified based on their size, shape, and location. Repetitive firing patterns and AP frequencies of individual neurons were examined by using the whole cell current clamp technique. AP kinetic analysis was defined within the range of AP initiation and 15 ms after trigger. Using this strategy, long EAD-like events during the late AP decay phase occurred beyond the defined range and were not included in analysis. CA1, CA3, and neocortical regions were examined for every mouse except in experiments designed for pharmacological analyses.

Data Analysis.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM, unless stated otherwise. Statistical significance was determined as indicated in figure legends and tables. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

SI Methods

Animals.

Scn8aN1768D/+ knock-in mice were generated as described (23, 24). All experiments were performed in accordance with NIH guidelines with approval from the University of Michigan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Scn8aN1768D/+ mice were maintained by backcrossing to inbred strain C57BL/6J. Experiments were performed by using male and female heterozygous mutant mice and WT littermate controls from backcrossed generations N4–N6 at postnatal day (P) 21–26.

Reagents.

Riluzole (Sigma) was dissolved in 0.1% DMSO. APV (Sigma) was dissolved in H2O. Tetrodotoxin with citrate (Biotium) was dissolved in H2O.

Preparation of Brain Slices.

Acute brain slices were prepared as described (51). In brief, the brain was rapidly removed following euthanasia by isoflurane inhalation and decapitation. Coronal brain slices (200 μm), containing both neocortical and hippocampal components, were prepared from postnatal day (P) 21–26 WT or Scn8aN1768D/+ mice in ice-cold, oxygenated slicing solution saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2. The slicing solution contained (in mM): 110 sucrose or 62.5 NMDG-Cl; 62.5 NaCl; 2.5 KCl; 6 MgCl2; 1.25 KH2PO4; 26 NaHCO3; 0.5 CaCl2; and 20 d-glucose (pH 7.35–7.4 when saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2 at room temperature of 21–22 °C). Slices were incubated in the same slicing solution for >30 min at room temperature and then in the mixture (1:1) of the slicing solution and ACSF (containing in mM: 125 NaCl; 2.5 KCl; 1 MgCl2; 1.25 KH2PO4; 26 NaHCO3; 2 CaCl2 and 20 d-glucose, (pH 7.35–7.4)] in a holding chamber aerated continuously with 95% O2/5% CO2 at 21–22 °C for at least another 30 min before use.

Acute Hippocampal Neuron Dissociation.

Brain slices were transferred to a dish containing cold, oxygen saturated HBSS (Gibco) with low calcium (1:10; HBSS with calcium and magnesium: HBSS calcium and magnesium free). The dentate gyrus was removed completely and then the hippocampal CA1 or CA3 region was microdissected and transferred to 35 °C and oxygen saturated HBSS with calcium and magnesium supplemented with 0.2 mM ascorbic acid and 1.5 mg/mL of protease type XIV (Sigma). After 23 min of incubation, the slice was rinsed three times with cold and oxygen saturated calcium-free HBSS. Finally, the HBSS solution was removed and 400 μL of cold, oxygen saturated, Na-isethionate solution (in mM; 140 Na-isethionate, 23 glucose, 15 Hepes, 2 KCl, 4 MgCl2, 0.1 CaCl2) was added. The tissue was then triturated by using silicon-coated Pasteur pipettes of decreasing tip sizes.

INa Recordings in Isolated Hippocampal Neurons.

Voltage clamp recordings from acutely dissociated CA1 and CA3 hippocampal neurons were performed in the standard whole-cell configuration, using previously described conditions (52). INa was evoked with a test pulse to −30 mV after a 250 ms prepulse to −120 mV. Isolated INa was recorded from single hippocampal neurons with bipolar or pyramidal morphology at room temperature (21–22 °C) in the presence of a bath solution containing (in mM): 30 NaCl, 1 BaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 45 CsCl, 0.2 CdCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 Hepes, 20 TEA-Cl, and 100 glucose (pH 7.35 with CsOH, osmolarity: 300–305 mOsM). Fire-polished patch pipettes were filled with an internal solution containing (in mM): 1 NaCl, 150 N-methyl-d-glucamine, 10 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 40 Hepes, 25 phosphocreatine-Tris, 2 MgATP, 0.02 Na2GTP, 0.1 Leupectin (pH 7.2 with H2SO4). All recordings were performed within 10–90 min after neurons were placed at the recording chamber. The voltage dependence of inactivation was recorded by using a standard two-pulse protocol (53, 54). Data were calculated with a single Boltzmann equation plus a constant to take into account INa,P.

Immunocytochemistry.

Coverslips containing acutely dissociated hippocampal neurons were fixed for 15 min in 4% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde (PFA), washed in PBS, and stored at 4 °C until use. Coverslips were processed for immunocytochemistry as described (55). Briefly, coverslips were dried and then postfixed for 5 min in 4% PFA, washed three times for 5 min with 0.05 M phosphate buffer (PB), then incubated in blocking buffer (10% goat serum, 0.3% Triton X-100, 0.1 M PB) for 2 h in a humidified chamber. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies (mouse anti-GAD67, 1:250, Millipore; rabbit anti-GABA,1:2,000 Sigma-Aldrich; or chicken anti-MAP2, 1:500, Millipore) diluted in blocking buffer overnight in a humidified chamber. The following day, coverslips were washed three times for 10 min with 0.1 M PB and then placed in the dark for all subsequent steps to minimize photobleaching of secondary antibodies. Coverslips were incubated with secondary antibodies (AlexaFluor goat anti-mouse 488 nm, AlexaFluor goat anti-chicken 568 nm, or AlexaFluor goat anti-rabbit 647 nm; Molecular Probes) diluted 1:500 in blocking buffer for 2 h, washed three times for 10 min in 0.1 M PB, air-dried, and mounted on glass slides by using ProLong Gold anti-fade reagent (Life Technologies). Coverslips were imaged by using a Nikon A1R confocal microscope and a 20× N.A. 0.75 dry objective. Images were acquired with Nikon NIS-Elements software and assembled by using NIH ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop.

Brain Slice Electrophysiology.

Each brain slice was transferred to a recording chamber where it was superfused (2–3 mL/min) with ACSF bubbled continuously with 95% O2/5% CO2. Pyramidal cells in neocortical or hippocampal slices were visually identified based on their size, shape, and location by using a NIKON E600FN upright microscope equipped with Nomarski optics (40× water immersion objective). Recording electrodes had a resistance of 3–6 MΩ when filled with the potassium gluconate (K-Gluconate)-based pipette solution consisting of (in mM): 140 K-gluconate; 4 NaCl; 0.5 CaCl2; 10 Hepes; 5 EGTA, 5 phosphocreatine; 2 Mg-ATP, and 0.4 GTP (pH 7.2–7.3 adjusted with KOH). Repetitive firing patterns and AP frequencies of individual neurons were examined by using the whole cell current clamp recording technique. Individual APs in neurons were evoked by injections of a series of 1-ms currents varying from subthreshold to suprathreshold stimuli in 10-pA steps from their resting membrane potentials. The threshold potential for AP initiation, peak amplitude, 50% (APD50) and 80% (APD80) repolarization width, area under the AP waveform, rise tau, and decay tau were measured by using the Event Detection tool in Clampfit. We defined AP kinetic analysis (rise and decay time constants and area) within the range of AP initiation and 15 ms after trigger. Using this strategy, long EAD-like events during the late AP decay phase occurred beyond the defined range and, thus, were not included in analysis. Repetitive AP firing was evoked by injection of a series of 1,500-ms currents varying from −80 pA to 220 pA in 10-pA steps from resting membrane potential. Signals were amplified with a Multiclamp 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices) and filtered at 2–4 kHz and digitized at 20 kHz for off-line analysis. Access resistances were usually less than 15 MΩ (usually 6–10 MΩ) with 70% series resistance compensation and monitored throughout the experiments to ensure their constancy. Data were acquired with a Digidata 1440A interface and analyzed by using pClamp10 offline. All experiments were carried out at 21–22 °C. In most experiments, 1 cell per brain region from each mouse was counted, for a sample size of n = 1. In experiments where more than 1 cell per brain region from a given mouse were examined, the data from that region were averaged such that the sample size was still considered to be n = 1. CA1, CA3, and neocortical layer II/III regions were examined for every mouse except in experiments design for pharmacological analysis of EAD-like responses in CA1 regions.

Data Analysis.

Data are presented as mean ± SEM, unless stated otherwise. Statistical significance was determined as indicated in figure legends and tables. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Grants R01-NS076752, R56-NS076752, and R01-NS088571 (to L.L.I.), R01-NS034509 (to M.H.M.) and Fellowships from T32HL007853 and UL1TR000433 (to C.R.F.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1616821114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.O’Brien JE, Meisler MH. Sodium channel SCN8A (Nav1.6): Properties and de novo mutations in epileptic encephalopathy and intellectual disability. Front Genet. 2013;4:213. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burgess DL, et al. Mutation of a new sodium channel gene, Scn8a, in the mouse mutant ‘motor endplate disease’. Nat Genet. 1995;10(4):461–465. doi: 10.1038/ng0895-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohrman DC, Harris JB, Meisler MH. Mutation detection in the med and medJ alleles of the sodium channel Scn8a. Unusual splicing due to a minor class AT-AC intron. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(29):17576–17581. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.29.17576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raman IM, Sprunger LK, Meisler MH, Bean BP. Altered subthreshold sodium currents and disrupted firing patterns in Purkinje neurons of Scn8a mutant mice. Neuron. 1997;19(4):881–891. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80969-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maurice N, Tkatch T, Meisler M, Sprunger LK, Surmeier DJ. D1/D5 dopamine receptor activation differentially modulates rapidly inactivating and persistent sodium currents in prefrontal cortex pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21(7):2268–2277. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-07-02268.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kearney JA, et al. Molecular and pathological effects of a modifier gene on deficiency of the sodium channel Scn8a (Na(v)1.6) Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11(22):2765–2775. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.22.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Do MT, Bean BP. Sodium currents in subthalamic nucleus neurons from Nav1.6-null mice. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92(2):726–733. doi: 10.1152/jn.00186.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meisler MH, et al. SCN8A encephalopathy: Research progress and prospects. Epilepsia. 2016;57(7):1027–1035. doi: 10.1111/epi.13422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammer MF, Wagnon JL, Mefford HC, Meisler MH. SCN8A-Related Epilepsy with Encephalopathy. In: Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews(R) University of Washington; Seattle: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Veeramah KR, et al. De novo pathogenic SCN8A mutation identified by whole-genome sequencing of a family quartet affected by infantile epileptic encephalopathy and SUDEP. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;90(3):502–510. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wagnon JL, Meisler MH. Recurrent and non-recurrent mutations of SCN8A in epileptic encephalopathy. Front Neurol. 2015;6:104. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2015.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carvill GL, et al. Targeted resequencing in epileptic encephalopathies identifies de novo mutations in CHD2 and SYNGAP1. Nat Genet. 2013;45(7):825–830. doi: 10.1038/ng.2646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen J, et al. EuroEPINOMICS RES Consortium CRP The phenotypic spectrum of SCN8A encephalopathy. Neurology. 2015;84(5):480–489. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mercimek-Mahmutoglu S, et al. Diagnostic yield of genetic testing in epileptic encephalopathy in childhood. Epilepsia. 2015;56(5):707–716. doi: 10.1111/epi.12954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allen AS, et al. Epi4K Consortium Epilepsy Phenome/Genome Project De novo mutations in epileptic encephalopathies. Nature. 2013;501(7466):217–221. doi: 10.1038/nature12439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Estacion M, et al. A novel de novo mutation of SCN8A (Nav1.6) with enhanced channel activation in a child with epileptic encephalopathy. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;69:117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kong W, et al. SCN8A mutations in Chinese children with early onset epilepsy and intellectual disability. Epilepsia. 2015;56(3):431–438. doi: 10.1111/epi.12925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanchard MG, et al. De novo gain-of-function and loss-of-function mutations of SCN8A in patients with intellectual disabilities and epilepsy. J Med Genet. 2015;52(5):330–337. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2014-102813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Kovel CG, et al. Characterization of a de novo SCN8A mutation in a patient with epileptic encephalopathy. Epilepsy Res. 2014;108(9):1511–1518. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2014.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barker BS, et al. The SCN8A encephalopathy mutation p.Ile1327Val displays elevated sensitivity to the anticonvulsant phenytoin. Epilepsia. 2016;57(9):1458–1466. doi: 10.1111/epi.13461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagnon JL, et al. Pathogenic mechanism of recurrent mutations of SCN8A in epileptic encephalopathy. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2015;3(2):114–123. doi: 10.1002/acn3.276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang B, et al. A BAC transgenic mouse model reveals neuron subtype-specific effects of a Generalized Epilepsy with Febrile Seizures Plus (GEFS+) mutation. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;35(1):91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones JM, Meisler MH. Modeling human epilepsy by TALEN targeting of mouse sodium channel Scn8a. Genesis. 2014;52(2):141–148. doi: 10.1002/dvg.22731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagnon JL, et al. Convulsive seizures and SUDEP in a mouse model of SCN8A epileptic encephalopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24(2):506–515. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sprissler RS, Wagnon JL, Bunton-Stasyshyn RK, Meisler MH, Hammer MF. Altered gene expression profile in a mouse model of SCN8A encephalopathy. Exp Neurol. 2017;288:134–141. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frasier CR, et al. Cardiac arrhythmia in a mouse model of sodium channel SCN8A epileptic encephalopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(45):12838–12843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612746113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iwamoto T, et al. The exchanger inhibitory peptide region-dependent inhibition of Na+/Ca2+ exchange by SN-6 [2-[4-(4-nitrobenzyloxy)benzyl]thiazolidine-4-carboxylic acid ethyl ester], a novel benzyloxyphenyl derivative. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66(1):45–55. doi: 10.1124/mol.66.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urbani A, Belluzzi O. Riluzole inhibits the persistent sodium current in mammalian CNS neurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(10):3567–3574. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grasse DW, Karunakaran S, Moxon KA. Neuronal synchrony and the transition to spontaneous seizures. Exp Neurol. 2013;248:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toyoda I, Fujita S, Thamattoor AK, Buckmaster PS. Unit activity of hippocampal interneurons before spontaneous seizures in an animal model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2015;35(16):6600–6618. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4786-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu Y, et al. Dravet syndrome patient-derived neurons suggest a novel epilepsy mechanism. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(1):128–139. doi: 10.1002/ana.23897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antzelevitch C, et al. The role of late I Na in development of cardiac arrhythmias. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;221:137–168. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-41588-3_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Auerbach DS, et al. Altered cardiac electrophysiology and SUDEP in a model of Dravet syndrome. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77843. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Enoki R, et al. NMDA receptor-mediated depolarizing after-potentials in the basal dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons. Neurosci Res. 2004;48(3):325–333. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2003.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghamari-Langroudi M, Bourque CW. Caesium blocks depolarizing after-potentials and phasic firing in rat supraoptic neurones. J Physiol. 1998;510(Pt 1):165–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.165bz.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.David G, Modney B, Scappaticci KA, Barrett JN, Barrett EF. Electrical and morphological factors influencing the depolarizing after-potential in rat and lizard myelinated axons. J Physiol. 1995;489(Pt 1):141–157. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1995.sp021037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brown CH, Ghamari-Langroudi M, Leng G, Bourque CW. Kappa-opioid receptor activation inhibits post-spike depolarizing after-potentials in rat supraoptic nucleus neurones in vitro. J Neuroendocrinol. 1999;11(11):825–828. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.1999.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim JH, Kushmerick C, von Gersdorff H. Presynaptic resurgent Na+ currents sculpt the action potential waveform and increase firing reliability at a CNS nerve terminal. J Neurosci. 2010;30(46):15479–15490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3982-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ghitani N, Bayguinov PO, Basso MA, Jackson MB. A sodium afterdepolarization in rat superior colliculus neurons and its contribution to population activity. J Neurophysiol. 2016;116(1):191–200. doi: 10.1152/jn.01138.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutnick MJ, Yarom Y. Low threshold calcium spikes, intrinsic neuronal oscillation and rhythm generation in the CNS. J Neurosci Methods. 1989;28(1-2):93–99. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(89)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Llinás R, Yarom Y. Electrophysiology of mammalian inferior olivary neurones in vitro. Different types of voltage-dependent ionic conductances. J Physiol. 1981;315:549–567. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1981.sp013763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Llinás R, Yarom Y. Oscillatory properties of guinea-pig inferior olivary neurones and their pharmacological modulation: An in vitro study. J Physiol. 1986;376:163–182. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1986.sp016147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blumenfeld H, et al. Role of hippocampal sodium channel Nav1.6 in kindling epileptogenesis. Epilepsia. 2009;50(1):44–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kohrman DC, Smith MR, Goldin AL, Harris J, Meisler MH. A missense mutation in the sodium channel Scn8a is responsible for cerebellar ataxia in the mouse mutant jolting. J Neurosci. 1996;16(19):5993–5999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-05993.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Martin MS, et al. The voltage-gated sodium channel Scn8a is a genetic modifier of severe myoclonic epilepsy of infancy. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16(23):2892–2899. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Makinson CD, Tanaka BS, Lamar T, Goldin AL, Escayg A. Role of the hippocampus in Nav1.6 (Scn8a) mediated seizure resistance. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;68:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baker E, et al. 2016 GS967 improves survival and reduces persistent current in a mouse model OF SCN8A encephalopathy. American Epilepsy Society Annual Meeting, https://www.aesnet.org Abstr. 2.179.

- 48.Han C, et al. Human Na(v)1.8: Enhanced persistent and ramp currents contribute to distinct firing properties of human DRG neurons. J Neurophysiol. 2015;113(9):3172–3185. doi: 10.1152/jn.00113.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Eberhardt M, et al. Inherited pain: Sodium channel Nav1.7 A1632T mutation causes erythromelalgia due to a shift of fast inactivation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(4):1971–1980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.502211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waxman SG. Mechanisms of disease: Sodium channels and neuroprotection in multiple sclerosis-current status. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2008;4(3):159–169. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pappalardo LW, Samad OA, Black JA, Waxman SG. Voltage-gated sodium channel Nav 1.5 contributes to astrogliosis in an in vitro model of glial injury via reverse Na+ /Ca2+ exchange. Glia. 2014;62(7):1162–1175. doi: 10.1002/glia.22671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shibuya K, et al. A single blind randomized controlled clinical trial of mexiletine in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Efficacy and safety of sodium channel blocker phase II trial. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2015;16(5-6):353–358. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2015.1038277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Noto Y, Shibuya K, Vucic S, Kiernan MC. Novel therapies in development that inhibit motor neuron hyperexcitability in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Expert Rev Neurother. 2016;16(10):1147–1154. doi: 10.1080/14737175.2016.1197774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Djamgoz MB, Onkal R. Persistent current blockers of voltage-gated sodium channels: A clinical opportunity for controlling metastatic disease. Recent Patents Anticancer Drug Discov. 2013;8(1):66–84. doi: 10.2174/15748928130107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rizaner N, et al. Intracellular calcium oscillations in strongly metastatic human breast and prostate cancer cells: Control by voltage-gated sodium channel activity. Eur Biophys J. 2016;45(7):735–748. doi: 10.1007/s00249-016-1170-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brackenbury WJ, Yuan Y, O’Malley HA, Parent JM, Isom LL. Abnormal neuronal patterning occurs during early postnatal brain development of Scn1b-null mice and precedes hyperexcitability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(3):1089–1094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208767110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Patino GA, et al. A functional null mutation of SCN1B in a patient with Dravet syndrome. J Neurosci. 2009;29(34):10764–10778. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2475-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lopez-Santiago LF, Brackenbury WJ, Chen C, Isom LL. Na+ channel Scn1b gene regulates dorsal root ganglion nociceptor excitability in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(26):22913–22923. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.242370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kruger LC, et al. β1-C121W is down but not out: Epilepsy-associated Scn1b-C121W results in a deleterious gain-of-function. J Neurosci. 2016;36(23):6213–6224. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0405-16.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]