Significance

Sensory neurons are often spontaneously active even in the absence of the relevant stimuli, raising the question, Is this background activity a bug or a feature of neural circuits? Using in vivo calcium imaging in mice, we show that neurons in the primary olfactory (piriform) cortex are spontaneously active when the animal is breathing unodorized air and this activity is entirely driven by spontaneous firing in the upstream olfactory bulb. When the animal smells an odor, some piriform neurons fire more strongly, and others have their spontaneous activity suppressed. By allowing two-way changes in firing, spontaneous background activity serves as a mechanism to extend the range of odor coding.

Keywords: olfaction, in vivo, calcium imaging, two-photon, anesthetic

Abstract

Neurons in the neocortex exhibit spontaneous spiking activity in the absence of external stimuli, but the origin and functions of this activity remain uncertain. Here, we show that spontaneous spiking is also prominent in a sensory paleocortex, the primary olfactory (piriform) cortex of mice. In the absence of applied odors, piriform neurons exhibit spontaneous firing at mean rates that vary systematically among neuronal classes. This activity requires the participation of NMDA receptors and is entirely driven by bottom-up spontaneous input from the olfactory bulb. Odor stimulation produces two types of spatially dispersed, odor-distinctive patterns of responses in piriform cortex layer 2 principal cells: Approximately 15% of cells are excited by odor, and another approximately 15% have their spontaneous activity suppressed. Our results show that, by allowing odor-evoked suppression as well as excitation, the responsiveness of piriform neurons is at least twofold less sparse than currently believed. Hence, by enabling bidirectional changes in spiking around an elevated baseline, spontaneous activity in the piriform cortex extends the dynamic range of odor representation and enriches the coding space for the representation of complex olfactory stimuli.

The brain remains intensely active even under conditions when overt external stimuli are absent (1). At first glance this behavior can seem puzzling. Pyramidal neurons in primary sensory neocortex, for example, typically fire spontaneously at approximately 1 Hz when the relevant stimuli are not present (2), raising the possibility that this background activity is noise that must be mitigated by signal averaging (3). On the other hand, spontaneous cortical activity is often structured (4) and can reflect the global state of the animal (5), suggesting that it is not simply an impediment but may serve a useful computational role. Indeed, such activity may be important for gating sensory inputs (4, 6), establishing and maintaining sensory maps (7–9), and extending the dynamic range of sensory-evoked responses (10, 11). The significance of spontaneous activity is also supported by theoretical studies showing that it emerges naturally from balanced neural networks with desirable information-processing characteristics (9, 12).

Given that spontaneous spiking is likely to be a key element of cortical function, it is important to study its prevalence and properties in different cortical areas. The piriform cortex (PC) is a sensory paleocortex in mammals that is critical for recognizing and remembering odors (13–17). The PC offers a number of advantages for the study of neural information processing, including a simple trilaminar architecture and well-defined afferent input from the olfactory bulb (OB) (16, 17). As a phylogenetically “old” structure, the PC is also likely to express canonical cortical circuits that have been conserved across evolution (18). Spontaneous spiking has been reported in the PC of rodents breathing odor-free air (19–23), but these studies used unit recordings, which provide a biased estimate of firing rates (2), and none of them identified the drivers or roles of this activity. Here we use two-photon calcium imaging and whole-cell patch clamping from identified PC neurons in vivo to measure the properties of stimulus-decoupled spiking. We find that this ongoing spiking allows a broader dynamic range of odor responsiveness, implying that the representation of odor information in the PC is considerably less sparse than is currently thought (20, 24).

Results

Spontaneous Spiking Occurs at Different Rates in Different Classes of Piriform Neurons.

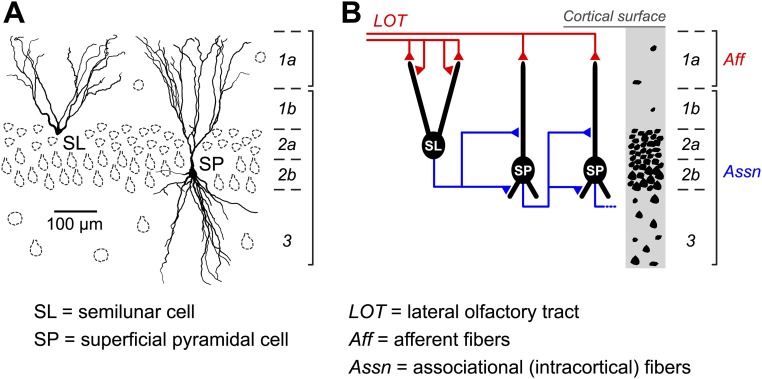

Using mice, we imaged somatic intracellular calcium (as a proxy for spiking) in layer 2 neurons of the anterior PC while the animals breathed clean air. Layer 2 of the PC contains the densely packed somas of glutamatergic cells of different types (Fig. S1A). The more superficial lamina (layer 2a) is enriched in semilunar (SL) cells, whereas the deeper lamina (layer 2b) mainly contains superficial pyramidal (SP) cells (Fig. S1A). Because SL and SP cells are likely to perform different functions in the PC circuit (Fig. S1B) (25, 26), we took care to study them separately by focusing on cells at different depths below the cortical surface (160–210 µm for SL cells and 250–300 µm for SP cells).

Fig. S1.

Glutamatergic neuronal types and schematic diagram of excitatory circuits in the mouse anterior PC. (A) Reconstructed dendritic arbors of an SL cell (Left) and an SP cell (Right) showing the approximate location of their somas in layer 2. Glutamatergic cells (notably, deep pyramidal cells) are also present at lower density in layer 3 but are not shown here. (B) Schematic of simplified excitatory circuits (Left) and cytoarchitecture (Right). SL cells receive stronger afferent (Aff) input than SP cells but much weaker associational (Assn) input.

Using the indicator Cal-520, we found that both SL and SP cells exhibited ongoing spontaneous somatic calcium transients in the absence of applied odors (Fig. 1A and Movie S1), and we obtained similar results with the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP6f. Control experiments showed that these transients were completely blocked by tetrodotoxin (TTX; 10 µM) applied to the cortical surface (n = 3 animals), indicating that they are sodium spike-driven. The transients occurred randomly, as was confirmed by the exponential distribution of interevent time intervals (linear fit to the logarithm of interval histogram; SL: r2 = 0.98, n = 5 mice, 5,609 events in 725 cells; SP: r2 = 0.98, n = 5 mice, 1,408 events in 275 cells).

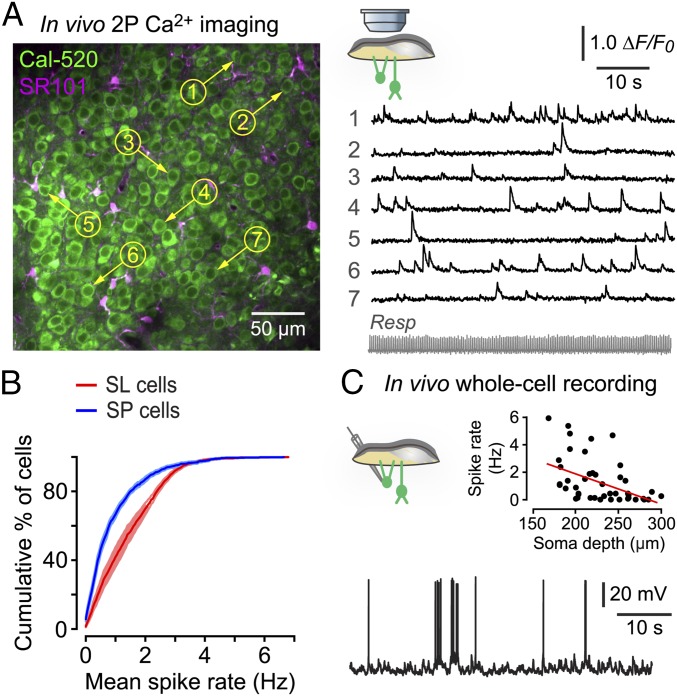

Fig. 1.

The PC is spontaneously active in vivo. (A) Cal-520–labeled SL cell somas (Left) and corresponding ∆F/F0 fluorescence traces from the numbered cells (Right) showing spontaneous activity. Resp, simultaneously recorded respiration. SR 101 labels astrocytes. (B) Averaged cumulative histograms showing that the mean spontaneous spike rate in SL cells (n = 7 mice, 1,928 cells) and SP cells (n = 6 mice, 1,005 cells; shaded regions are ± SEM) are significantly different (P < 0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). (C) A typical in vivo whole-cell recording showing spontaneous spiking in an SL cell (depth 166 µm). (Inset) The spontaneous spike rate was higher in the more superficial SL cells (soma depth 160–230 µm, 1.7 ± 0.3 Hz; mean ± SEM) than in the deeper SP cells (230–300 µm, 0.7 ± 0.2 Hz; mean ± SEM, P = 0.005, Mann–Whitney test) and was negatively correlated with recording depth (r = 0.47, P = 0.0006, n = 50 cells from 48 mice; F test on linear regression).

To convert the calcium transient rate to an action potential rate, we calibrated one of our indicators (Cal-520) by measuring spontaneous calcium fluorescence transients in a single SL or SP cell in vivo while simultaneously recording spikes in that cell via a patch electrode (Fig. S2). Applying this calibration to our imaging dataset, we found that the mean spontaneous spike rate was significantly higher in SL cells than in SP cells (SL: 1.24 ± 0.04 Hz, mean ± SEM, n = 7 mice, total 1,928 cells; SP: 0.74 ± 0.05 Hz, n = 6 mice, 1,005 cells; significantly different, P < 0.0001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) (Fig. 1B).

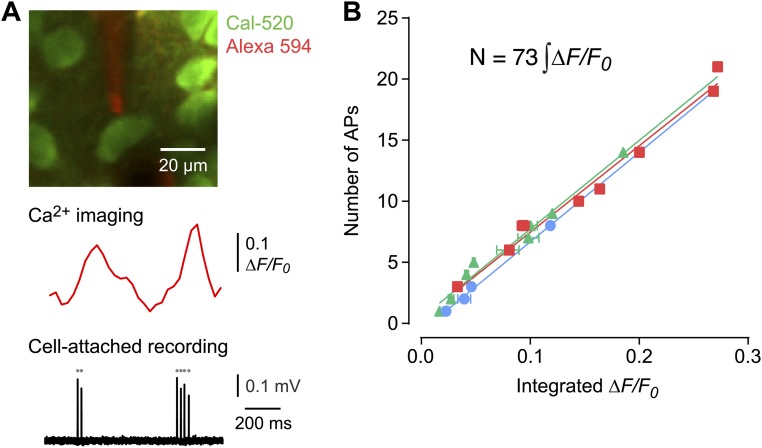

Fig. S2.

Calibration procedure for converting measured calcium transients to spike number. (A, Upper) Simultaneous two-photon Ca2+ imaging and cell-attached recording in vivo from a Cal-520–labeled SL cell. The pipette solution contained Alexa-Fluor 594 (50 µM). (Lower) Typical ∆F/F0 trace and corresponding spikes recorded via the patch electrode. (B) Plot of integrated ∆F/F0 versus the number of simultaneously recorded spikes. Each color indicates data from a different neuron (n = 22 data points from three cells from two mice). A straight line fitted to all data points had a slope of 73 ± 1 spikes per unit area under the ∆F/F0 waveform (mean ± SD, R2 > 0.98).

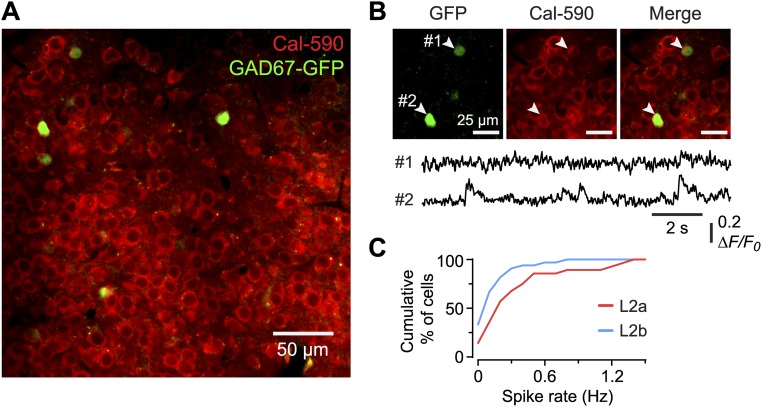

To confirm that the majority of cells imaged were indeed glutamatergic, we repeated these experiments using the red-shifted calcium indicator Cal-590 in GAD67-GFP mice, in which GABAergic interneurons express GFP (Fig. S3) (27). We confirmed that interneurons comprise a small fraction (approximately 4%) of layer 2 neurons in the PC, consistent with previous reports (28). Thus, most of the neurons imaged in layer 2 are glutamatergic (SL and SP cells). Interestingly, GFP+ interneurons also exhibited spontaneous spiking activity (Fig. S3 B and C).

Fig. S3.

Identification of GABAergic interneurons confirms that most of the neurons imaged in layer 2 are glutamatergic (SL and SP cells). Furthermore, interneurons in layer 2 also exhibit spontaneous activity. (A) Typical image of neurons in layer 2a loaded with the red-shifted calcium indicator Cal-590 AM in a urethane-anesthetized transgenic GAD67-GFP mouse. Interneurons (green) are scarce (approximately 4% of the total number of neurons), confirming a previous report (28). Similar results were obtained in layer 2b. (B) Typical ∆F/F0 traces (Lower) showing spontaneous activity in two identified interneurons (Upper, arrowheads). (C) Cumulative histogram showing the spontaneous spike rate of interneurons in layer 2a or layer 2b (2a: mean 0.35 ± 0.07 Hz, n = 28 cells; 2b: 0.14 ± 0.03 Hz, n = 33 cells; P = 0.065, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). The spike rate was calibrated using a different method from that shown in Fig. S2 for Cal-520 AM. See SI Materials and Methods for details.

In Vivo Patch-Clamp Experiments Confirm the Calcium Imaging Results.

To validate the findings from the calcium imaging, we turned to in vivo whole-cell patch clamping. Spontaneous spiking was measured at the resting potential of each neuron while the animal breathed odor-free air (Fig. 1C). These experiments confirmed that the spontaneous spike rate was higher in the more superficial SL cells (soma depth 160–230 µm, 1.7 ± 0.3 Hz, mean ± SEM, n = 28 cells) than in the deeper SP cells (230–300 µm, 0.7 ± 0.2 Hz, mean ± SEM, n = 22 cells; P = 0.005, Mann–Whitney test). In addition, the spontaneous spike rate was negatively correlated with recording depth (P = 0.0006, n = 50 cells from 48 mice; F test on linear regression) (Fig. 1C, Inset). Thus, both patch clamping and imaging show that SL and SP cells are spontaneously active, with a higher spontaneous firing rate in SL cells than in SP cells.

Spontaneous Spiking Requires NMDA Receptors.

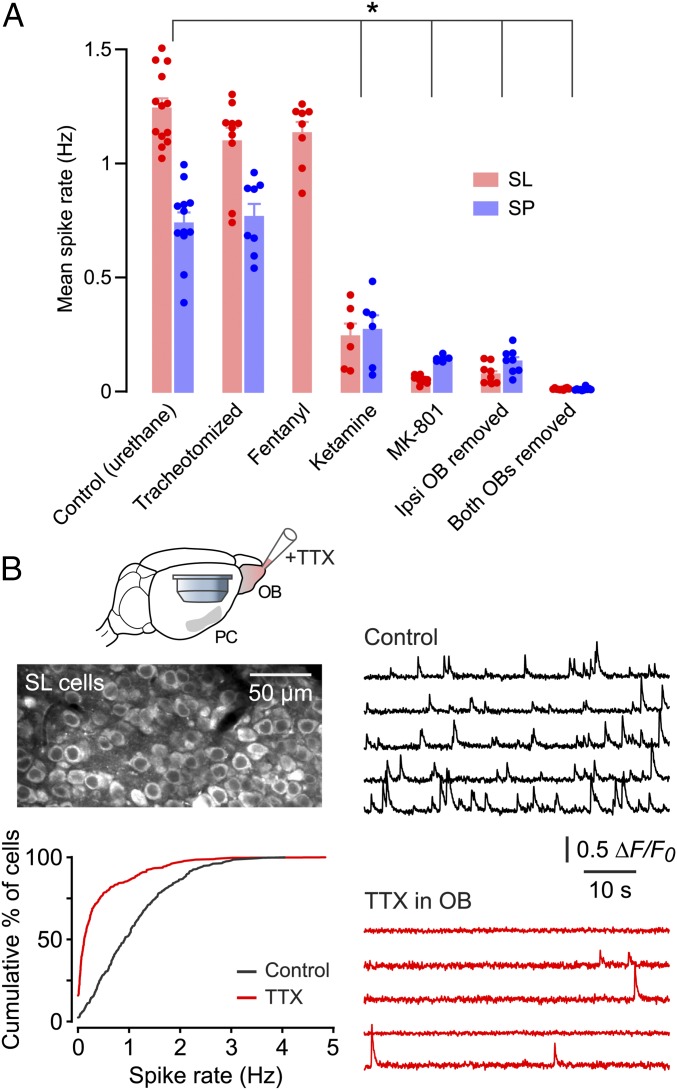

Because the difficult surgical access to the PC precludes the use of awake animals, we sought to validate our findings under different anesthetics. Spontaneous spiking was similar under urethane and fentanyl/medetomidine anesthesia [SL cells in fentanyl: 1.13 ± 0.05 Hz, mean ± SEM, n = 2 mice, 612 cells; not significantly different from corresponding control (urethane) values, P > 0.1, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test; only SL cells were imaged in fentanyl] (Fig. 2A). Fentanyl/medetomidine is thought to produce a more awake-like brain state (29). Surprisingly, spiking was significantly reduced under ketamine/xylazine anesthesia (combined SL and SP data: 0.26 ± 0.04 Hz, mean ± SEM, n = 2 mice, total 1,328 cells; significantly smaller than corresponding control values, P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test) (Fig. 2A). This result may help explain why spontaneous activity was not seen in the only previous in vivo calcium imaging study in the PC, which used ketamine/xylazine (24).

Fig. 2.

Properties of spontaneous spiking in SL and SP cells under different experimental conditions. (A) Each data point is the averaged firing rate for all cells (n approximately 60–230 cells) in a field of view in a single experiment. Bars show mean ± SEM of the points. *P < 0.05 (one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test, comparing control with other conditions in SL cells and SP cells separately). SP cells were not imaged in fentanyl. (B, Upper Left) Imaged field of SL cells in this experiment (using Cal-520). (Right) ∆F/F0 traces for the same five SL cells recorded before (control, Upper) and during (Lower) the superfusion of TTX over the ipsilateral OB. (Lower Left) Cumulative histograms of spontaneous spike rates recorded in this experiment before (black trace) and during (red trace) TTX application. P < 0.0001 (n = 368 cells, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test).

Given that ketamine blocks NMDA channels, we asked whether local application of the NMDA channel blocker MK-801 (1 mM) to the PC would also suppress spontaneous spiking. We found that it did so (SL: 0.05 ± 0.01 Hz, mean ± SEM, n = 3 mice, 1,728 cells; SP: 0.14 ± 0.01 Hz, n = 2 mice, 352 cells; both significantly smaller than corresponding controls, P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test) (Fig. 2A). Thus, spontaneous spiking in the PC depends critically on NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission.

Spontaneous Activity in the PC Is Driven Entirely by the OB.

What drives spontaneous spiking in the PC? Mechanosensitive effects of nasal airflow across the olfactory epithelium (30) are not involved, because tracheotomizing mice to bypass the nasal airway did not alter the activity (SL: 1.10 ± 0.06 Hz, mean ± SEM, n = 3 mice, 1,659 cells; SP: 0.77 ± 0.06 Hz, n = 3 mice, 406 cells; not significantly different from corresponding controls, P > 0.1, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test) (Fig. 2A). However, silencing the afferent input from the ipsilateral OB, either surgically or by locally applying TTX (10 µM) to the OB, reduced spontaneous spiking in the PC (combined SL and SP data: 0.25 ± 0.05 Hz, mean ± SEM, n = 5 mice, 2,453 cells; significantly smaller than control, P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test in Fig. 2A, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test in Fig. 2B). Removal of both OBs abolished all activity in the PC (combined SL and SP data: 0.01 ± 0.00 Hz, mean ± SEM, n = 3 mice, 2,162 cells; significantly smaller than control, P < 0.0001, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test) (Fig. 2A). These data indicate that input from the OB is required for spontaneous spiking activity in the PC.

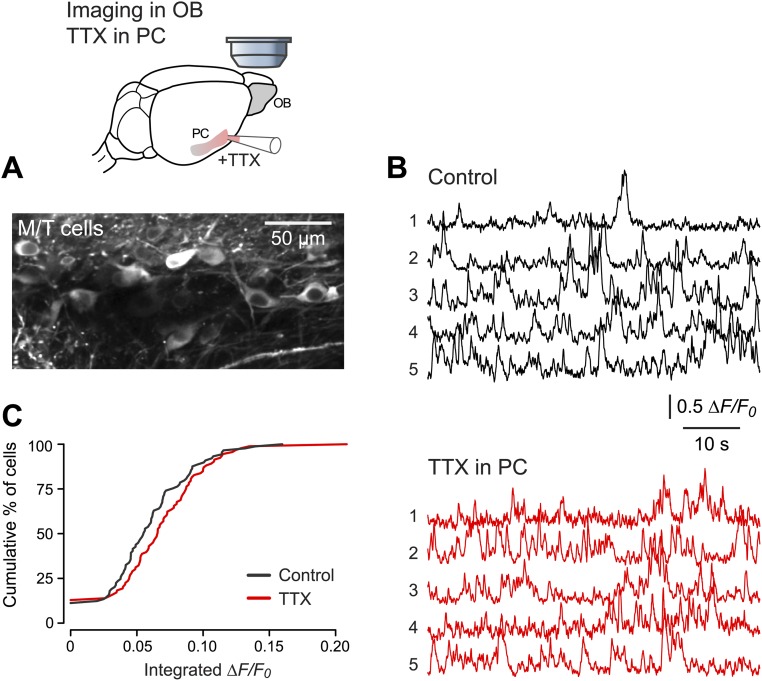

Our findings suggest that the projection cells in the OB, the mitral/tufted (M/T) cells, are spontaneously active in the absence of applied odors. Imaging in the bulb confirmed this suggestion (Fig. S4) (31). Interestingly, local application of TTX to the PC had no effect on spontaneous spiking in M/T cells (n = 93 M/T cells, P = 0.11, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) (Fig. S4 B and C). This result suggests that only OB → PC connections are important for spontaneous spiking in the PC and that connections in the reverse direction (PC → OB) are not involved (32–34).

Fig. S4.

Pharmacological silencing of the PC has no effect on spontaneous spiking in the ipsilateral OB. (A, Upper) Schematic of the imaging of M/T cells in the OB using the genetically encoded indicator GCaMP6f while activity in the ipsilateral anterior PC was silenced by superperfusing TTX through a craniotomy made over the PC. (Lower) A typical field of view. (B) Representative ∆F/F0 traces showing spontaneous activity measured simultaneously in the same population of five M/T cells before (black traces) and during (red traces) the application of TTX. (C) Cumulative histograms of integrated ΔF/F0 in M/T cells before (black trace) and during (red trace) TTX application to the ipsilateral anterior PC. There was no significant difference in spontaneous activity (n = 93 M/T cells, P = 0.11, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test).

Odors both Excite and Suppress Spontaneous Activity.

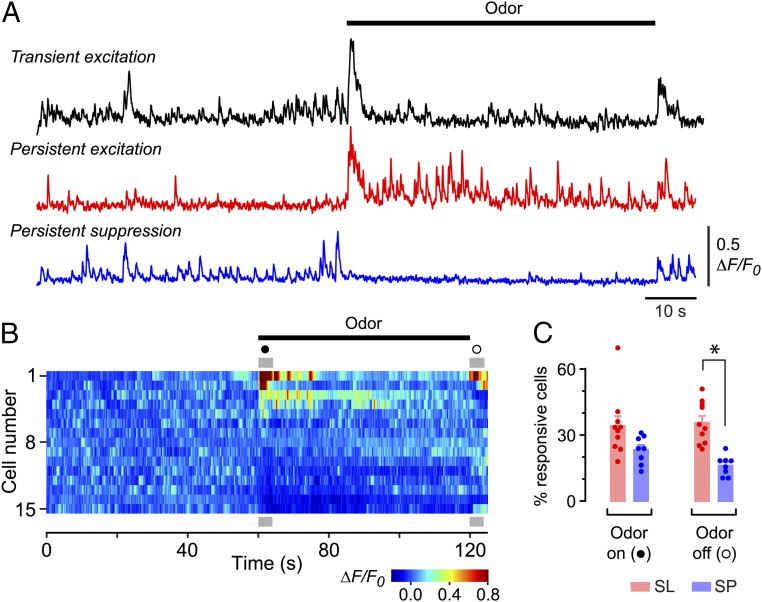

How does this spontaneous spiking activity influence the way exogenous odors are detected by the PC? To address this question, we used two-photon calcium imaging to record the effect of prolonged (60-s) steps of odorant on SL and SP cell activity. The responses were heterogeneous: Some cells showed transient excitation at odor onset, others were persistently activated throughout the odor application, and still others were suppressed (Fig. 3A using Cal-520 and Movie S2 using GCaMP6f). The variety of responses in a typical experiment is shown in Fig. 3B, which is a color raster plot of activity in a sample of SL cells ordered by their activity in the first 4 s after odor onset (filled circle in Fig. 3B). A gradient of responsiveness is apparent, ranging from excitation (warm colors just after odor onset; top) to inhibition (cool colors just after onset; bottom), with a subset of cells showing no response (middle). Similar distinctions were seen at odor offset (open circle in Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Odors both excite and suppress spiking activity. (A) ∆F/F0 recordings from three different layer 2 cells showing the typical diversity of odor responses. The indicator was Cal-520. (B) Color raster plot of ∆F/F0 in a selected subset of SL cells in one experiment, ranked by their peak ∆F/F0 during the first 4 s after odor application. Gray bars designate 4 s after odor onset (●) and offset (O). (C) Percentages of SL and SP cells that were responsive (i.e., were either excited or suppressed) during odor onset or offset. Bars show mean ± SEM of the individual experiments (points). *P < 0.001 (n = 10 SL and n = 8 SP experiments, unpaired two-tailed t test).

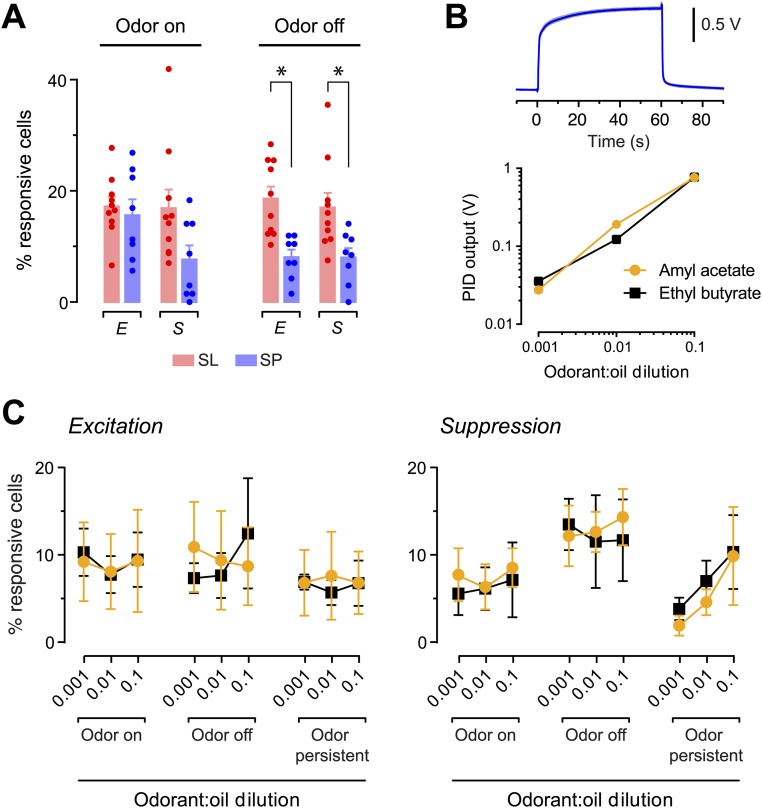

These data were quantified by using a statistical criterion to measure the percentage of cells either excited or suppressed at odor onset or offset (Fig. S5). This analysis indicated that a similar percentage of SL and SP cells was responsive to odor onset (SL: 34.1 ± 4.5% of cells, mean ± SEM, n = 10 imaging fields tested with six odors; SP: 23.3 ± 2.3%, n = 8 fields and five odors; P = 0.063; two-sample t test) (Fig. 3C). In contrast, fewer SP cells responded at odor offset (SL: 35.6 ± 3.0%, mean ± SEM; SP: 16.1 ± 1.6%; P < 0.0001; two-sample t test) (Fig. 3C). Similar results were obtained if excitation and suppression were considered separately (Fig. S6A) and if the odor concentration was varied over two orders of magnitude (Fig. S6 B and C). Furthermore, we found no significant differences between any of these measures when comparing responses to different odors (one-way ANOVA, all P > 0.05). In summary, spontaneous activity allows odor-driven bidirectional changes in spiking around an elevated baseline. Although there are some differences between SL and SP cells, the percentage of responsive cells is independent of odor identity and concentration.

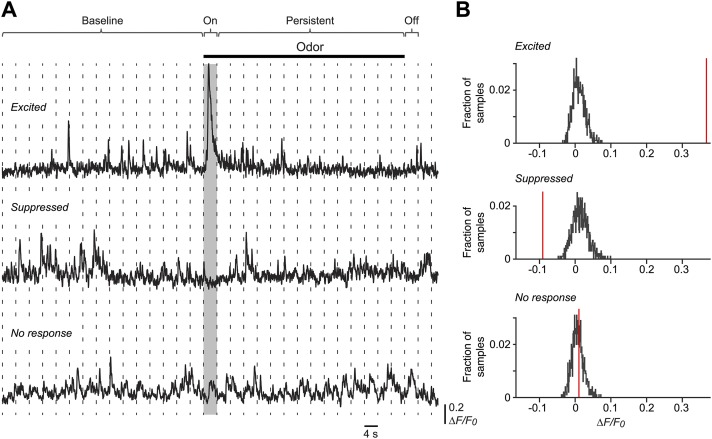

Fig. S5.

Method for finding whether a cell is excited or suppressed by odor. (A) Representative ∆F/F0 traces of cell somas with significant responses (Top, excited; Middle, suppressed) or with no response (Bottom) during the first 4 s of odor presentation (on response; gray box). The significance of these responses was estimated using a bootstrapping procedure as described in SI Materials and Methods. Briefly, the ∆F/F0 traces were divided into 4-s segments (dashed vertical lines), each containing 120 frames; then the ∆F/F0 values for each cell soma were bootstrapped 500 times for each segment, and a histogram of these values was calculated. The histograms for all fifteen 4-s segments during the 60-s baseline period were averaged to yield an average background distribution for each cell; examples of these for three different cells are shown in B. A similar procedure was used for the 4-s on and off periods (except that no averaging was done) and for the 56-s persistent period. (B) Results of the analysis for the cells shown in A. Histograms around zero are the averaged ∆F/F0 values of the baseline period, and the red vertical line indicates the median of the distribution of bootstrapped ∆F/F0 values measured in the 4-s odor-on test period. The cell was scored as excited if the median was above the 99.9th percentile of the baseline distribution (Top), as suppressed if the median was below the 0.1th percentile (Middle), and otherwise was scored as showing no response (Bottom). A similar analysis was done for the 4-s odor-off period.

Fig. S6.

SL and SP cells differ significantly in the percentages that are excited or suppressed by odor, but only at the odor-off period. In addition, changing the odor concentration has little effect on the percentages of SL cells that are excited or suppressed by the odor. (A) Percentages of SL cells (red) and SP cells (blue) that are excited (E) or suppressed (S) at either the onset or offset of a 60-s application of the odor. Colored bars and error bars indicate mean ± SEM. Filled circles indicate the percentage of responsive cells measured in each experiment. *P < 0.05 (n = 10 SL and n = 8 SP experiments, unpaired two-tailed t test). (B, Upper) Output of the photo ionization device (PID). Five consecutive trials are shown (gray traces, all overlapping and indistinguishable), together with their average (blue trace). These data show that odor pulses are reproducible and that odor concentration does not decline during the 60-s application period. (Lower) Log-log plot of PID output versus dilution factor for two odorants, confirming dilution. (C) Percent of SL cells that are excited (Left) or suppressed (Right) by two different odorants (amyl acetate, yellow; ethyl butyrate, black) applied at three different dilutions. Measurements were made in three different time periods: on, i.e., the first 4 s after odor onset; off, i.e., the first 4 s after odor offset; persistent, a period from 4–60 s after odor onset. Symbols and error bars indicate mean ± SEM. For each time period and each odorant, the percentage of responsive cells was not significantly different among the three odor concentrations (n = 4 experiments per data point, one-way ANOVA).

Balanced Excitation and Suppression.

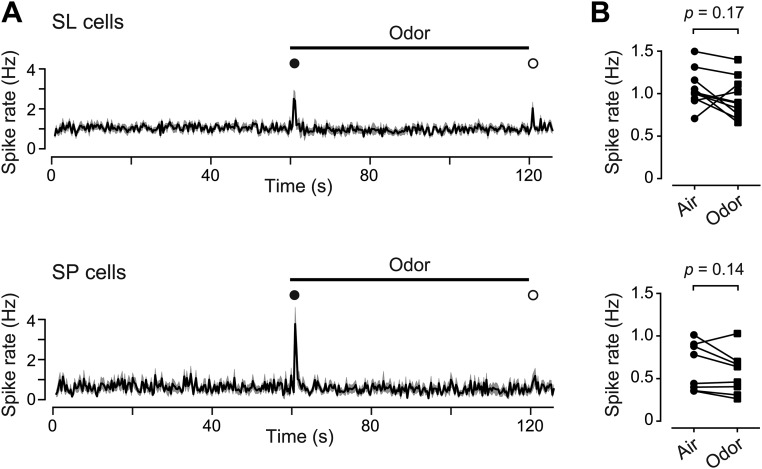

Given that odors both excite and suppress firing in PC neurons, we wondered if the net effect was to keep firing in equilibrium. Indeed, when averaged across all SL cells or all SP cells in our dataset, the mean spike rate during the odor was not significantly different from that in unodorized air, except at odor onset and offset (Fig. S7). Thus, following a perturbation of the olfactory stimulus, excitation and suppression are quickly balanced to keep the net population activity constant (35).

Fig. S7.

The spike rate, averaged over the population of SL and SP cells, shows only transient increases at odor onset and offset. (A) Mean population spike rate in clean air (first 60 s) and in odor (60–120 s) in SL cells (Upper, n = 10 imaged fields) and SP cells (Lower, n = 8 imaged fields). Odor onset and offset are labeled with filled and open symbols, respectively. Shading indicates ± SEM. (B) Spike rate averaged over either the 60-s clean-air baseline period or the subsequent 60-s period of odor application, for SL cells (Upper) and SP cells (Lower). Each pair of symbols shows the average from a single imaged field of view (the same dataset as in A). The mean rate was not significantly different between the two time windows (n = 10 SL and n = 8 SP experiments, paired two-tailed t test).

Relationship Between Spontaneous Firing Rate and Odor Responsiveness.

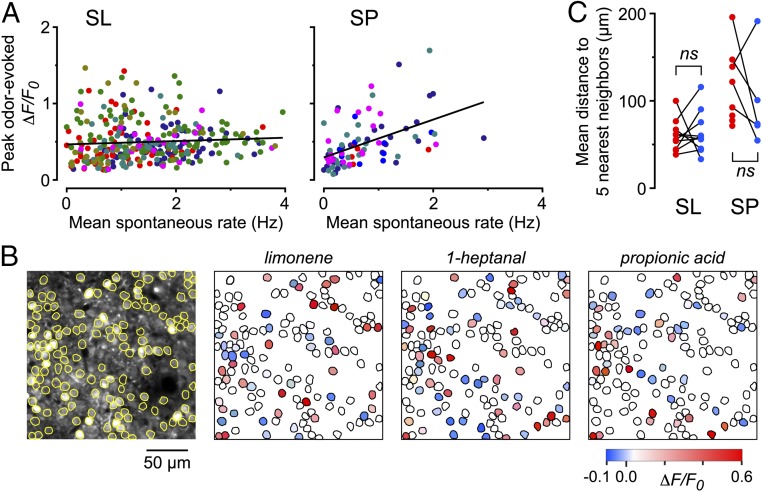

We next asked whether cells with a higher spontaneous firing rate also exhibited a stronger odor response, given that both types of activity are driven by bulbar input. We tested this notion by plotting the peak odor-evoked ΔF/F0 in each odor-responsive cell versus the mean spontaneous rate for that cell (Fig. 4A). SP cells exhibited a significant correlation, but SL cells did not (SL: P = 0.20, n = 321 cells; SP: P < 0.001, n = 83 cells; F test on linear regression). Thus, in SP cells the input that drives odor responsiveness is closely related to the input that drives spontaneous activity, but this association is absent in SL cells.

Fig. 4.

Properties of odor-evoked excitation and suppression. (A) Each point shows the peak odor-evoked response in an odor-excited neuron plotted versus the mean spontaneous spike rate measured in the same neuron. Different colors indicate different odors. Superimposed straight lines indicate a correlation for SP cells (slope = 0.25, correlation coefficient = 0.48, n = 83 cells) but not for SL cells (slope = 0.02, correlation coefficient = 0.07, n = 321 cells). (B, Left) Imaged field of SL cells with somatic ROIs outlined. The other three panels show the same ROIs with color-coded odor responses to the three odors indicated. The indicator was GCaMP6f. (C) Each red point indicates the mean distance between each excited cell in an imaged field and its five nearest neighbors that also were excited, averaged across all excited cells in that field. Blue points show the same measure for suppressed cells. Lines connect data from the same experiment (n = 10 experiments for SL cells, n = 8 experiments for SP cells). In three SP cell experiments (red points without connected blue points) there were fewer than six suppressed cells in the imaged field. ns, not significant (P > 0.5, unpaired two-tailed t test).

Excited and Suppressed Neurons Form Spatially Dispersed, Odor-Distinctive Patterns.

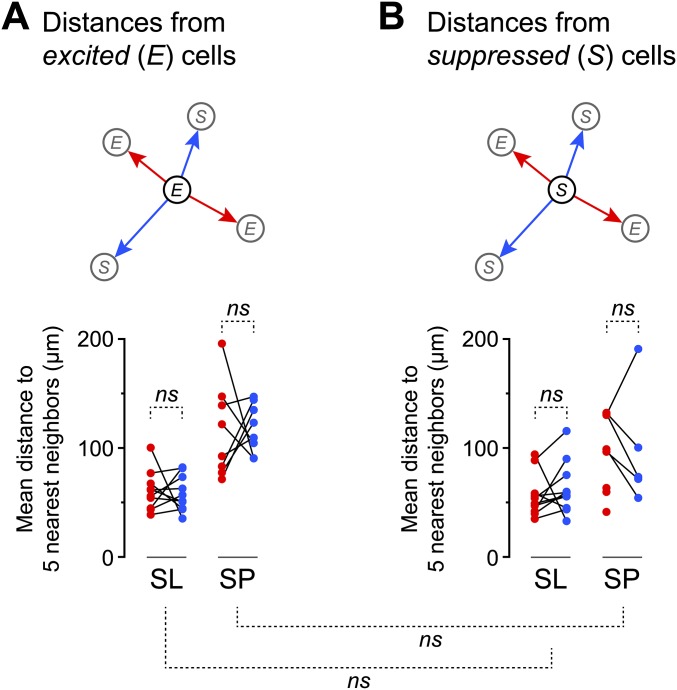

As noted above (Fig. 3C and Fig. S6), different odors could not be distinguished by the mean responsiveness of SL or SP cells (i.e., the fraction of cells excited or suppressed). On the other hand, it is known that different odors produce distinctive, spatially dispersed patterns of excited principal neurons in the PC (red somas, Fig. 4B) (20, 24); these patterns are thought to form the basis of odor identification by the PC (15–17). We found a similar effect for suppression: Odors also produced distinctive, spatially dispersed patterns of suppression of SL and SP cells at both odor onset and offset (blue somas in Fig. 4B; similar results were obtained in 10 experiments). We quantified this effect by calculating, separately for excitation and suppression, the mean distance between each odor-responsive neuron in the imaged field and its five nearest odor-responsive neighbors. These mean distances then were averaged across all odor-excited or odor-suppressed neurons in each imaging experiment (red and blue points, respectively, in Fig. 4C). The mean distance between odor-excited and odor-suppressed neurons was not significantly different across all experiments (SL: 60.3 ± 5.7 µm for excitation, 63.7 ± 7.7 µm for suppression, mean ± SEM, both n = 10 experiments, P = 0.73; SP: 116.1 ± 15.2 µm for excitation, n = 8, 98.5 ± 24.3 µm for suppression, n = 5, P = 0.53; two-sample t test) (Fig. 4C). Similar results were obtained when we measured the mean distance to all (not just to the nearest five) odor-responsive neighbors in the imaged field. We also asked if excited cells tended to be located near suppressed cells, or if the two types of cells were randomly intermingled in a salt-and-pepper arrangement. An analysis similar to that described above confirmed the salt-and-pepper model (Fig. S8). Thus, odors both excite and suppress layer 2 principal cells in a manner that lacks any obvious spatial pattern.

Fig. S8.

The mean distances between odor-excited and odor-suppressed SL or SP cells are similar, suggesting that excited and suppressed cells are randomly intermingled. (A) The red points in this panel are the same as those in Fig. 4C of the main text and show the mean distance between each excited (E) cell in an imaged field and its five nearest neighbors that were also excited, averaged across all excited cells in that field (n = 10 experiments for SL cells; n = 8 experiments for SP cells). In contrast to Fig. 4C, the blue points in this panel show the mean distance between each excited cell and its five nearest neighbors that were suppressed (S) by odor (not to be confused with the blue points in Fig. 4C, which show distances between suppressed cells.) Lines connect data from the same experiment. Mean distances are not significantly different for SL and SP cells (SL: 60.3 ± 5.7 µm for E–E, 57.9 ± 5.2 µm for E–S, mean ± SEM, n = 10, P = 0.77; SP: 116.1 ± 15.2 µm for E–E, 118.1 ± 8.0 µm for E–S, n = 8, P = 0.91; unpaired two-tailed t test). (B) As in A, except that the points now show the mean distance from each suppressed cell to its five nearest-neighbor excited cells (red points) or suppressed cells (blue points). In three SP cell experiments (red points without connected blue points) there were fewer than six suppressed cells in the imaged field. Mean distances are not significantly different for SL and SP cells (SL: 56.7 ± 6.3 µm for S–E, 63.7 ± 7.7 µm for S–S, n = 10, P = 0.49; SP: 94.6 ± 12.7 µm for S–E, n = 8, 98.5 ± 24.3 µm for S–S, n = 5, P = 0.88; unpaired two-tailed t test). Finally, the mean distance from each excited cell to its neighbors (both excited and suppressed) was not significantly different from the mean distance from each suppressed cell to its neighbors (dashed lines connecting panels A and B; SL: P = 0.85; SP: P = 0.14; unpaired two-tailed t test). ns, not significant.

Discussion

Spontaneous firing in the absence of overt input is commonly observed in sensory neocortex, as well as in many other brain regions, and its prevalence may suggest that it is a feature, not a bug, of neural circuits (2–4). Here we confirm that spontaneous firing is also a feature of a sensory paleocortex, the PC. We find that spontaneous activity in the anterior PC strictly requires bottom-up input from the OB (Fig. 2A) and differs significantly between classes of principal cells (i.e., SL and SP cells) in its main input layer, layer 2 (Figs. 1B, 2A, 3C, and 4A). Importantly, we also find that spontaneous spiking activity increases the dynamic range of odor representations in the anterior PC by defining a set point around which odor stimulation can produce either excitation or suppression of spiking activity (Fig. 3B). By expanding the definition of odor responsiveness in this way, we find that at least twice as many layer 2 neurons respond to odors than previously thought; i.e., approximately 25–35% respond at odor onset (Fig. 3C), rather than the approximately 3–15% reported previously (24).

Before proceeding, we address two potential weaknesses of our study. First, the use of anesthesia can be problematic (36), but it was required in our experiments because of the invasive surgery needed to access the surface of the PC (24). To address this issue, we confirmed that two different anesthetics (urethane/chlorprothixene and fentanyl/medetomidine) gave identical results. Previous work using unit recordings in awake mice has reported spontaneous firing in layer 2 PC neurons at approximately 0.6–3.5 Hz (21), compared with approximately 0.7–1.2 Hz here (Fig. 2A). Keeping in mind that unit recordings are biased toward more active cells, we believe that our results are in line with what occurs in awake animals. Given our finding that ketamine/xylazine inhibits spontaneous activity (Fig. 2A), we recommend avoiding this anesthetic for PC experiments (see also ref. 34).

A second potential concern is the use of calcium imaging as an imperfect proxy for spikes. We mitigated this concern by using the calcium indicators Cal-520 and GCaMP6f, which are at least 10-fold more sensitive than Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (OGB-1) (37) used in the one previous calcium imaging study in the PC (24). We confirmed that OGB-1 could not detect spontaneous activity in the PC (n = 7 imaging fields in two mice). Despite our improved sensitivity, single spikes were not reliably detected in our imaging experiments (Fig. S2), implying that the firing rate is underestimated. The patch-clamp experiments (Fig. 1C) were not subject to this limitation and confirmed the difference in the spontaneous firing rate in SL and SP cells (Fig. 1B). Hence, imaging may underestimate absolute spike rates, but relative comparisons remain valid.

The higher spontaneous firing rate in SL cells is consistent with previous reports that SL cells receive stronger afferent input from the OB (25, 26), which we have shown here is the primary driver of spontaneous activity. SP cells receive much stronger associational input than SL cells, and some of this input comes from the contralateral PC (25). However, removal of the ipsilateral OB almost completely abolished spontaneous activity (Fig. 2A), implying that little spontaneous input comes via associational fibers from the contralateral PC. Another difference between SL and SP cells is that only SP cells show a correlation between spontaneous and odor-evoked activity (Fig. 4A). This correlation may reflect the stronger associational connections received by SP cells that might amplify, in parallel, the spontaneous and odor-evoked excitation received from the OB. A functional consequence may be that SP cells, but not SL cells, maintain a stable signal-to-noise ratio over a range of inputs (38).

We were surprised to find that spontaneous activity in the PC was driven entirely by feed-forward excitation from the OB (Fig. 2A, both OBs removed). The anterior PC is the recipient of excitatory input from a number of other brain areas, including the anterior olfactory nucleus, orbitofrontal cortex, entorhinal cortex, and amygdala (39, 40), but we found no sign of residual spontaneous drive after OB removal. However, it remains possible that intracortical and descending inputs could contribute to spontaneous activity in the awake state. The anterior PC also sends corticobulbar axons back to the OB (32, 33, 41), but, again, we found no evidence for the contribution of a reciprocal OB ↔ PC loop in the generation of spontaneous excitation in the PC (Fig. S4). Two recent reports have described spontaneous calcium transients in boutons on corticobulbar axons in the OB (33, 34). Their presence implies that the sources of those axons, SP cells in the anterior PC (42), are also spontaneously active, consistent with our findings.

Turning to odor-evoked responses, we observed a heterogeneity of response patterns (Fig. 3 and Fig. S5). However, when averaging across all imaged neurons in all experiments, the mean spike rate increased only at odor onset and offset, suggesting that global excitation and suppression are normally balanced in an unchanging olfactory environment (Fig. S7). These properties are suited to a mechanism enabling animals to follow odor plumes or scent trails (43). Gradients in odor concentration at the edges of the plume may be efficiently encoded by “on” and “off” responses, whereas a more stable concentration within the plume may be represented by the neurons that exhibit persistent excitation or suppression. Interestingly, a similar diversity of odor-evoked responses was recently reported in the lateral entorhinal cortex (44), suggesting that it may be a general feature of odor-processing circuits.

How might the enhancement or suppression of spontaneous spiking be incorporated into a mechanism for encoding odors? As in other cortical regions, the rate of spontaneous spiking in the PC is low, approximately 1 Hz (Fig. 1B). However, the PC is thought to use a rate code (22, 45) and is able to identify odors quickly (46). Thus, if changes in the low rate of spontaneous firing are to represent information on a fast timescale, the PC or higher areas need to compute averaged firing rates across many neurons simultaneously. This computation must be achieved without erasing information about odor identity that is thought to be encoded in the spatially distinctive patterns of activity elicited by different odors (Fig. 4B). How this task might be implemented (47, 48) is an intriguing question for future work.

In summary, we have found that spontaneous activity in the anterior PC is inherited from the OB, differs between types of principal cells, and can be suppressed by odors. Our results suggest that spontaneous spiking can extend the dynamic range of odor representations in the PC, enhancing the ability of this sensory paleocortex to encode complex olfactory information.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Anesthesia.

All procedures involving mice were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the Australian National University and conform to the guidelines of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Experiments used male or female, 50- to 70-d-old C57BL6/J mice. Mice were anesthetized with urethane + chlorprothixene (0.7 g/kg s.c. and 5 mg/kg s.c., respectively), ketamine + xylazine (100 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively), or fentanyl + medetomidine (0.1 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg, respectively).

Surgery.

To access the anterior PC, overlying muscle and bone were sequentially dissected, and then a craniotomy (approximately 1.5 × 1.5 mm) was opened over the region where the middle cerebral artery (MCA) and the dorsal aspect of the lateral olfactory tract (LOT) intersect. The dura was removed also. A water-tight chamber was constructed around the surgical site to accommodate the water-immersion objective. The chamber was filled with Ringer’s solution containing (in mM) 135 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 Hepes at pH 7.4, and drugs were applied by perfusing this chamber.

Calcium Indicators.

We used three types of calcium indicators in this study: the green dye Cal-520 AM, its red-shifted variant Cal-590 AM, and the green genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP6f. Cal-520 AM or Cal-590 AM (1 mM; AAT Bioquest) was pressure-injected into the PC at a depth of 200–300 µm with a micropipette. Sulforhodamine (SR) 101 (50 µM) was added to the Cal-520 solution to label astrocytes. Calcium imaging was performed at least 30 min after dye loading. For imaging with GCaMP6f, virus (AAV1.Syn.Flex.GCaMP6f.WPRE.SV40 + AAV1.hSyn.Cre.WPRE.hGH, from the University of Pennsylvania Vector Core) was stereotaxically injected into the PC or OB in mice anesthetized with isoflurane. Imaging was performed 2–3 wk later.

Two-Photon Imaging.

Imaging was done using a customized Thorlabs two-photon microscope with a 16× water-immersion objective (0.8 NA; Nikon), resonant galvanometer scanners, and a Ti:Sapphire laser (Chameleon Ultra; Coherent). Time-series movies were captured at 30 or 60 frames/s.

Odor Stimulation.

To measure spontaneous activity, a constant flow (0.5 L/min) of charcoal-filtered and humidified medical-grade air was delivered to the nares of the mouse. Odor stimulation used a custom-built 16-channel flow dilution olfactometer to deliver odorized air into the clean air stream. The performance of the olfactometer was confirmed using a photo-ionization detector (miniPID; Aurora Scientific) (Fig. S6B).

Whole-Cell Recordings.

Blind whole-cell current clamp recordings were obtained from layer 2 neurons using a patch pipette (5–7 MΩ) filled with an intracellular solution containing (in mM) 135 KMeSO4, 7 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 EGTA, 2 Na2-ATP, 0.3 Na3-GTP, 10 Hepes, adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH and an osmolarity of 290 mOsm/kg.

Analysis.

Analysis was done with ImageJ and custom MATLAB code (MathWorks). The raw fluorescence intensity of each region of interest (ROI) was calculated and expressed as ∆F/F0 = (F − F0)/F0, where F0 is the median of the lower 80% of values during the clean air period. Transients in the ∆F/F0 trace were detected using a sliding template (49). Excitation and suppression were determined using a bootstrapping procedure to determine appropriate thresholds. False-positive rates were estimated to be <1.7%.

A full description of experimental procedures is found in SI Materials and Methods.

SI Materials and Methods

Animals and Anesthesia.

All animal housing, breeding, and surgical procedures were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the Australian National University and conform to the guidelines of the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Experiments used 50- to 70-d-old male or female C57BL6/J mice housed in groups of fewer than five in cages kept in a 12-h/12-h light/dark cycle. For interneuron imaging (Fig. S3), some experiments used transgenic GAD67-GFP (Δneo) mice in which GFP is specifically expressed in neurons containing GABA (50). Mice were anesthetized with chlorprothixene (5 mg/kg s.c.) and urethane (0.7 g/kg s.c.). Some experiments used ketamine + xylazine (100 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively) or fentanyl + medetomidine (0.1 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg, respectively). Anesthesia induction was supplemented with atropine (0.2 mg/kg), and skin incisions were treated with a local anesthetic (prilocaine, 0.2 mg/kg). Depth of anesthesia was monitored throughout the experiment; when necessary, a top-up dose (10–30% of the initial dose) was given. Body temperature was maintained at 36–37 °C using a heating blanket.

Surgery and Drug Application.

All experiments used the anterior PC, defined as that part of the PC rostral to the caudal limit of the LOT. More specifically, all our recordings were done within an approximately 1-mm2 region just posterior to the MCA and just dorsal to the LOT. To expose the anterior PC, the temporomandibular muscle, the zygomatic arch, and the upper portions of the mandible, including the coronoid and the condyloid processes, were dissected sequentially. A craniotomy (approximately 1.5 × 1.5 mm) was opened over the region where the MCA and the dorsal aspect of the LOT intersect. The dura was removed also. Using dental cement (Paladur; Heraeus), we attached a headpost to the skull for head fixation and then constructed a water-tight chamber around the surgical site to accommodate the water-immersion objective. The craniotomy was filled with Ringer’s solution containing (in mM) 135 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 1.8 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 Hepes at pH 7.4. In a subset of experiments, MK801 (1 mM) or TTX (10 µM) was dissolved in the Ringer’s solution and applied to the piriform surface. In pilot experiments we verified that the drug applications effectively perfused into the deep layers of PC by topically applying TTX and observing the subsequent silencing of spontaneous activity (typically within 15 min) in layer 2/3 neurons. Some experiments were conducted in tracheotomized mice or mice in which the ipsilateral OB or both OBs were removed by suction.

Loading of Calcium Indicator Dye.

Experiments with indicator dye used either Cal-520 AM or, for interneuron imaging in GAD67-GFP mice (Fig. S3), its red-shifted variant, Cal-590 AM (AAT Bioquest). A 10-mM stock solution was prepared in DMSO containing 20% Pluronic F-127 and then was diluted further in 0.9% saline to give a final concentration of 1 mM. SR 101 (50 µM) was added to the Cal-520 solution to label astrocytes. The solution was pressure injected into the PC at a depth of 200–300 µm with a micropipette (2–7 MΩ, 4–10 psi, 1 min). Calcium imaging was performed at least 30 min after dye loading.

Expression of GCaMP6f Calcium Indicator.

Some of the PC imaging and all the OB imaging used the genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP6f (37). For PC experiments, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (1–2%) and chlorprothixene (5 mg/kg s.c.), and a small craniotomy (0.25–0.5 mm in diameter) was made over the right forebrain. Virus (50 nL AAV1.Syn.Flex.GCaMP6f.WPRE.SV40 + 50 nL AAV1.hSyn.Cre.WPRE.hGH, from the University of Pennsylvania Vector Core) was stereotaxically injected into the PC (anteroposterior 0.6 mm, mediolateral 3.6 mm, dorsoventral 3.9 mm from bregma) using a 35-gauge needle (beveled NanoFil; World Precision Instruments) at a rate of 100 nL/min. The needle remained in place undisturbed for 5 min to allow the virus bolus to spread and then was retracted stepwise over a further 10-min period. The craniotomy was sealed with bone wax, and the incision was closed. Imaging was performed 2–3 wk later, as described above. For OB experiments, a similar injection procedure was used. A small craniotomy (0.25–0.5 mm in diameter) was made over the most caudal part of the right OB, and virus (200 nL) was injected into the OB at a depth of 200–400 µm. On the day of imaging, 2–3 wk later, a craniotomy (approximately 1.5 × 1.5 mm) was drilled over the dorsal OB, and a water-tight chamber was constructed using dental cement as described above.

Two-Photon Imaging.

A piece of a no. 0 glass coverslip was cut to fit inside the craniotomy and was glued in place. Imaging was done using a Thorlabs two-photon microscope with a 16× water-immersion objective (0.8 NA; Nikon), resonant galvanometer scanners, and a Ti:Sapphire laser (Chameleon Ultra; Coherent). Excitation wavelengths were 810 nm for Cal-520, SR 101, and GFP, 785 nm for Cal-590, and 920 nm for GCaMP6f. The x–y image-scanning plane was set to be parallel to the surface of the PC within a 300 × 300 µm (512 × 512 pixels) or 300 × 150 µm (512 × 256 pixels) imaging frame, and time-series movies were captured at 30 or 60 frames/s, respectively. SL and SP cells were distinguished by their depth below the pia (160–210 µm and 250–300 µm, respectively) and by their soma diameter (approximately 15 µm and approximately 20 µm, respectively).

Odor Stimulation.

During imaging, a constant flow (0.5 L/min) of charcoal-filtered and humidified medical-grade air was delivered to the nares of the mouse. Imaging done in this clean air stream was used to record spontaneous activity during 1- to 3-min movies. Respiration was monitored using a piezoelectric strap around the chest. Odor stimulation used a custom-built 16-channel flow dilution olfactometer to deliver odorized air into the clean air stream. A computer-controlled manifold valve switched the airflow to odorized air (10% of saturated vapor pressure) for 60 s and then back to clean air while keeping the overall flow constant. In some experiments (Fig. S6) odorants were diluted 10- to 1,000-fold in pure mineral oil. To ensure a stepwise on/off odor pulse, odorized air was preloaded for 5 s before its delivery to the nares. To minimize cross-contamination between odorants, each odorant was delivered using separate tubing and manifold valves, and the mixing manifold and downstream tubing were made of Teflon. Between trials clean air was pushed through the olfactometer continuously for at least 3 min. The performance of the olfactometer was confirmed using a photo-ionization detector (miniPID; Aurora Scientific) (Fig. S6B). The odors used were ethanol, 1-pentanol, 1-heptanal, limonene, eugenol, 2-heptanone, and acetophenone (all from Sigma-Aldrich), butyric acid, benzaldehyde, and anisole (all from Fluka), ethyl butyrate and propionic acid (both from BDH), amyl acetate (MP Biomed), isoamyl acetate (MPI), and lavender (Purity Australia).

Whole-Cell Recordings.

Blind whole-cell current-clamp recordings were obtained from layer 2 neurons using a patch pipette (5–7 MΩ) filled with an intracellular solution containing (in mM) 135 KMeSO4, 7 NaCl, 2 MgCl2, 0.1 EGTA, 2 Na2-ATP, 0.3 Na3-GTP, 10 Hepes, adjusted to pH 7.2 with KOH and an osmolarity of 290 mOsm/kg. The pipette was inserted at an 18° angle to the pial surface to the desired depth. Data were acquired using a Multiclamp 700A or 700B amplifier (Molecular Devices), filtered at 10 kHz, and digitized at 20 kHz. SL and SP cells could be distinguished by both their soma depth and their voltage responses to current steps (25). Cells with unstable or depolarized resting membrane potentials (above −55 mV) were excluded from analysis.

Calibration Recordings.

Two-photon targeted cell-attached recordings were made from layer 2 neurons that had previously been loaded with Cal-520 AM. Pipettes contained Ringer’s solution and Alexa 594 (50 µM) to enable visualization of the electrode (Fig. S2A). After establishment of the loose-seal cell-attached configuration, spontaneous cell-attached spikes and calcium transients were recorded simultaneously. Cell-attached recordings were filtered at 4 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz using a Multiclamp 700B, and calcium imaging was done as described above.

Quantification of Fluorescence Changes.

Fluorescence changes were analyzed with ImageJ (https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) and custom MATLAB code (MathWorks). Images in each time-series movie were registered using the ImageJ plugin Turboreg, and ROIs were drawn manually for each individual soma (excluding astrocytes labeled with SR 101) in the average registered image. Sometimes we observed brightly fluorescent somas in which the nucleus was not clearly visible; these were assumed to be damaged neurons and were excluded from the analysis (37). The raw fluorescence intensity of each ROI was calculated and expressed as ∆F/F0 = (F − F0)/F0, where F0 is the median of the lower 80% of values during the clean-air period. Transients in the ∆F/F0 trace were detected using a sliding template as described previously (49). The template used with Cal-520 was a product of two exponentials with rise and decay time constants of 60 ms and 600 ms, respectively, and the detection threshold was set to 2. All analysis was done using unfiltered traces, but a moving-average three-point filter was used to smooth the traces shown in the figures.

Calibration of Spike Rate.

To convert ∆F/F0 transients to spike rate, simultaneous imaging and cell-attached recordings were obtained as described above. Bursts of spikes in the cell-attached traces were identified and sorted into groups containing the same number of spikes. The corresponding ∆F/F0 transients were averaged together to obtain a smooth waveform. Then the number of spikes in each burst was plotted against the integral of the smoothed ∆F/F0 waveform (n = 2 SL cells and n = 1 SP cell from two animals) (Fig. S2B). A straight line fitted to all points had a slope of 73 ± 1 spikes per unit of area under the ∆F/F0 waveform (mean ± SD, R2 > 0.98). This calibration curve allowed us to convert the ∆F/F0 transients to mean spike rate (Hz). Note that single spikes were not reliably detected from the fluorescence; thus, the mean spike rate determined in this way will likely be an underestimate, with the size of the error depending on the relative number of single spikes. A different procedure was used to calibrate the red-shifted dye Cal-590 AM (Fig. S3), which has lower affinity for Ca2+ than Cal-520 (Cal-520: Kd = 320 nM; Cal-590: Kd = 561 nM). This procedure assumed that the spontaneous spike rates were equal in principal cells imaged with either Cal-520 or Cal-590. Thus, RCal-520 = CF × RCal-590, where RCal-520 is the mean spike rate of principal cells imaged using Cal-520, RCal-590 is the corresponding rate imaged with Cal-590, and CF is a correction factor. Solving for CF gave a value of 2.50, which then was used to convert the ∆F/F0 measurements in interneurons using Cal-590 to the mean spike rate (Fig. S3C).

Analysis of Excitation and Suppression.

Odor-evoked increases and decreases in ∆F/F0 were analyzed using a nonparametric method described previously (33). For each cell soma, the ∆F/F0 trace was divided into four time periods (Fig. S5): (i) the 60-s baseline period before odor application; (ii) the first 4 s after odor onset (on period); (iii) the remaining 56 s of the 60 s odor period (persistent period); and (iv) the first 4 s after the end of odor application (off period). The 60-s baseline period was divided into fifteen 4-s epochs, each containing 120 frames, and the ∆F/F0 for each epoch and each cell was bootstrapped 500 times with replacement to obtain a frequency distribution for each epoch. Then all 15 distributions were averaged together to obtain a smoothed baseline fluorescence distribution for each cell (Fig. S5B). A similar analysis was done for the 4-s on and off periods, except that only a single bootstrapped fluorescence distribution was obtained, and the median of this distribution was calculated (red vertical lines in Fig. S5B). A cell was scored as significantly excited if this median exceeded the 99.9th percentile of the baseline distribution. Conversely, a cell was scored as suppressed if the median was less than the 0.1th percentile of the baseline distribution. Finally, a similar analysis was done for the 56-s persistent period, except that the median was calculated from the average of 14 (56/4) bootstrapped fluorescence distributions (Fig. S6C). False-positive rates were calculated using the same procedure as in clean-air trials (n = 8): on, 1.2 ± 0.3% and 0.9 ± 0.4% for excited and suppressed responses, respectively; off, 1.5 ± 0.4% and 1.7 ± 0.5% for excited and suppressed responses, respectively; persistent, 1.1 ± 0.4% and 0.9 ± 0.7% for excited and suppressed responses, respectively.

Statistical Analysis.

Calculations were done using Prism 6.0 (GraphPad), MATLAB, and R (https://www.r-project.org/). Data were tested for normality using a D'Agostino–Pearson omnibus normality test; data with P > 0.05 were considered to have a normal distribution. Difference in variances was assessed using an F test; data with P > 0.05 were considered to have equal variances. Pairwise statistical comparisons of data with equal variances used the two-tailed t test (Fig. 3C and Fig. S6A). Pairwise comparisons of nonparametric data were done using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test (Fig. 1B) or Mann–Whitney test (Fig. 1C). Groups of three or more normal data were compared using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (Fig. 2A). Multiple linear regression was done using the lm function in R. Sample sizes were not predetermined using a statistical test, but sample sizes are similar to those commonly used in the field. Data collection and analysis were not blinded or randomized, but analysis was automated whenever possible.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Brian Billups, Mark McDonnell, and Greg Stuart for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by Project Grants 1009382 and 1050832 from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1620939114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Raichle ME. The restless brain: How intrinsic activity organizes brain function. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370(1668):20140172. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barth AL, Poulet JF. Experimental evidence for sparse firing in the neocortex. Trends Neurosci. 2012;35(6):345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brette R. Philosophy of the spike: Rate-based vs. spike-based theories of the brain. Front Syst Neurosci. 2015;9:151. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2015.00151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luczak A, McNaughton BL, Harris KD. Packet-based communication in the cortex. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015;16(12):745–755. doi: 10.1038/nrn4026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGinley MJ, et al. Waking state: Rapid variations modulate neural and behavioral responses. Neuron. 2015;87(6):1143–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luczak A, Bartho P, Harris KD. Gating of sensory input by spontaneous cortical activity. J Neurosci. 2013;33(4):1684–1695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2928-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu CR, et al. Spontaneous neural activity is required for the establishment and maintenance of the olfactory sensory map. Neuron. 2004;42(4):553–566. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lorenzon P, et al. Circuit formation and function in the olfactory bulb of mice with reduced spontaneous afferent activity. J Neurosci. 2015;35(1):146–160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0613-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panas D, et al. Sloppiness in spontaneously active neuronal networks. J Neurosci. 2015;35(22):8480–8492. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4421-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khubieh A, Ratté S, Lankarany M, Prescott SA. Regulation of cortical dynamic range by background synaptic noise and feedforward inhibition. Cereb Cortex. 2016;26(8):3357–3369. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takahashi N, Oertner TG, Hegemann P, Larkum ME. Active cortical dendrites modulate perception. Science. 2016;354(6319):1587–1590. doi: 10.1126/science.aah6066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostojic S. Two types of asynchronous activity in networks of excitatory and inhibitory spiking neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(4):594–600. doi: 10.1038/nn.3658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isaacson JS. Odor representations in mammalian cortical circuits. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20(3):328–331. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottfried JA. Central mechanisms of odour object perception. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11(9):628–641. doi: 10.1038/nrn2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murthy VN. Olfactory maps in the brain. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2011;34:233–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson DA, Sullivan RM. Cortical processing of odor objects. Neuron. 2011;72(4):506–519. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bekkers JM, Suzuki N. Neurons and circuits for odor processing in the piriform cortex. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36(7):429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fournier J, Müller CM, Laurent G. Looking for the roots of cortical sensory computation in three-layered cortices. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2015;31:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson DA. Habituation of odor responses in the rat anterior piriform cortex. J Neurophysiol. 1998;79(3):1425–1440. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.3.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poo C, Isaacson JS. Odor representations in olfactory cortex: “Sparse” coding, global inhibition, and oscillations. Neuron. 2009;62(6):850–861. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhan C, Luo M. Diverse patterns of odor representation by neurons in the anterior piriform cortex of awake mice. J Neurosci. 2010;30(49):16662–16672. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4400-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miura K, Mainen ZF, Uchida N. Odor representations in olfactory cortex: Distributed rate coding and decorrelated population activity. Neuron. 2012;74(6):1087–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lottem E, Lörincz ML, Mainen ZF. Optogenetic activation of dorsal Raphe serotonin neurons rapidly inhibits spontaneous but not odor-evoked activity in olfactory cortex. J Neurosci. 2016;36(1):7–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3008-15.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stettler DD, Axel R. Representations of odor in the piriform cortex. Neuron. 2009;63(6):854–864. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki N, Bekkers JM. Two layers of synaptic processing by principal neurons in piriform cortex. J Neurosci. 2011;31(6):2156–2166. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5430-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choy JM, et al. Optogenetic mapping of intracortical circuits originating from semilunar cells in the piriform cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2015:bhv258. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhv258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki N, Bekkers JM. Distinctive classes of GABAergic interneurons provide layer-specific phasic inhibition in the anterior piriform cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20(12):2971–2984. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suzuki N, Bekkers JM. Inhibitory neurons in the anterior piriform cortex of the mouse: Classification using molecular markers. J Comp Neurol. 2010;518(10):1670–1687. doi: 10.1002/cne.22295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Constantinople CM, Bruno RM. Effects and mechanisms of wakefulness on local cortical networks. Neuron. 2011;69(6):1061–1068. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Connelly T, et al. G protein-coupled odorant receptors underlie mechanosensitivity in mammalian olfactory sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(2):590–595. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418515112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wachowiak M, et al. Optical dissection of odor information processing in vivo using GCaMPs expressed in specified cell types of the olfactory bulb. J Neurosci. 2013;33(12):5285–5300. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4824-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boyd AM, Sturgill JF, Poo C, Isaacson JS. Cortical feedback control of olfactory bulb circuits. Neuron. 2012;76(6):1161–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otazu GH, Chae H, Davis MB, Albeanu DF. Cortical feedback decorrelates olfactory bulb output in awake mice. Neuron. 2015;86(6):1461–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boyd AM, Kato HK, Komiyama T, Isaacson JS. Broadcasting of cortical activity to the olfactory bulb. Cell Reports. 2015;10(7):1032–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Large AM, Vogler NW, Mielo S, Oswald AM. Balanced feedforward inhibition and dominant recurrent inhibition in olfactory cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(8):2276–2281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519295113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sellers KK, Bennett DV, Hutt A, Fröhlich F. Anesthesia differentially modulates spontaneous network dynamics by cortical area and layer. J Neurophysiol. 2013;110(12):2739–2751. doi: 10.1152/jn.00404.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen TW, et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature. 2013;499(7458):295–300. doi: 10.1038/nature12354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sakata S, Harris KD. Laminar structure of spontaneous and sensory-evoked population activity in auditory cortex. Neuron. 2009;64(3):404–418. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haberly LB. Parallel-distributed processing in olfactory cortex: New insights from morphological and physiological analysis of neuronal circuitry. Chem Senses. 2001;26(5):551–576. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.5.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Illig KR. Projections from orbitofrontal cortex to anterior piriform cortex in the rat suggest a role in olfactory information processing. J Comp Neurol. 2005;488(2):224–231. doi: 10.1002/cne.20595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Markopoulos F, Rokni D, Gire DH, Murthy VN. Functional properties of cortical feedback projections to the olfactory bulb. Neuron. 2012;76(6):1175–1188. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Johnson DMG, Illig KR, Behan M, Haberly LB. New features of connectivity in piriform cortex visualized by intracellular injection of pyramidal cells suggest that “primary” olfactory cortex functions like “association” cortex in other sensory systems. J Neurosci. 2000;20(18):6974–6982. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06974.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Geffen MN, Broome BM, Laurent G, Meister M. Neural encoding of rapidly fluctuating odors. Neuron. 2009;61(4):570–586. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leitner FC, et al. Spatially segregated feedforward and feedback neurons support differential odor processing in the lateral entorhinal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(7):935–944. doi: 10.1038/nn.4303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haddad R, et al. Olfactory cortical neurons read out a relative time code in the olfactory bulb. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(7):949–957. doi: 10.1038/nn.3407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Uchida N, Mainen ZF. Speed and accuracy of olfactory discrimination in the rat. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6(11):1224–1229. doi: 10.1038/nn1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rao RP, Ballard DH. Predictive coding in the visual cortex: A functional interpretation of some extra-classical receptive-field effects. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2(1):79–87. doi: 10.1038/4580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grabska-Barwińska A, et al. A probabilistic approach to demixing odors. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20(1):98–106. doi: 10.1038/nn.4444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clements JD, Bekkers JM. Detection of spontaneous synaptic events with an optimally scaled template. Biophys J. 1997;73(1):220–229. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78062-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamamaki N, et al. Green fluorescent protein expression and colocalization with calretinin, parvalbumin, and somatostatin in the GAD67-GFP knock-in mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467(1):60–79. doi: 10.1002/cne.10905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.