Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this investigation was to describe cancer survivorship based on the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) cancer survivorship modules in Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi, conducted in 2012 and 2014, and to investigate disparities across the US Deep South region.

Methods

The optional BRFSS cancer survivorship module was introduced in 2009. Data from Alabama (2012), Georgia (2012), and Mississippi (2014) were assessed. Demographic factors were analyzed through weighted regression for risk of receiving cancer treatment summary information and follow-up care.

Results

Excluding nonmelanoma skin cancer cases, a total of 1105 adults in the Alabama 2012 survey, 571 adults in the Georgia 2012 survey, and 442 adults in the 2014 Mississippi survey reported ever having cancer and were available for analysis. Among Alabamians, those with a higher level of education (odds ratio [OR] 1.4, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–1.7) and higher income (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1–1.6) were more likely to receive a written summary of their cancer treatments. Adults older than age 65 were only half as likely to receive a written summary of cancer treatments compared with adults 65 years or younger (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.8). We found no significant differences in receipt of treatment summary by race or sex. Among those who reported receiving instructions from a doctor for follow-up care, these survivors tended to have a higher level of education, higher income, and were younger (younger than 65 years). Receipt of written or printed follow-up care was positively associated with higher income (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–1.8) and inversely associated with age older than 65 years (OR 0.9, 95% CI 0.1–0.6) in Georgia.

Conclusions

Addressing the gap identified between survivorship care plan development by the health team and the delivery of it to survivors is important given the evidence of disparities in the receipt of survivorship care plans across survivor age and socioeconomic status in the Deep South.

Keywords: cancer, survivorship, health disparities, health literacy, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

Based on data released from the American Cancer Society, nearly 14.5 million children and adult cancer survivors were alive on January 1, 2014 in the United States.1 In 2006, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on Cancer Survivorship published a report on cancer survivorship and recommended that a survivorship care plan (SCP) be provided to all patients. One section of the SCP should focus on treatment information, including the type of cancer, the stage and date of diagnosis, specific treatment dates, and expected adverse effects. The specific SCP section may include a plan for scheduling follow-up visits and tests, surveillance of signs of cancer recurrence or long-term effects of treatment, lifestyle recommendations, and a list of available community resources related to survivorship.2,3

A study based on a survey of physicians’ attitudes regarding the care of cancer survivors in 2009 found, however, that <5% of oncologists provided written SCPs to their patients.4 A similar study conducted during the first half of 2013 found that more than half (56%) of all respondents reported that SCPs were not in use and did not reach survivors or primary care providers.5 The authors noted that SCP use was negatively associated with freestanding cancer program type as compared with academic institutions.6 Although the percentages of providers reporting the use of SCP should increase over time per IOM guidelines, the content and method of delivery of SCPs continue to evolve.

Because of the diverse and increasing needs of cancer survivors, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed an action plan to improve cancer survivorship. Based on information from the comprehensive cancer control plan development, the CDC has ranked the public health needs of cancer survivors; policy, system, and environmental changes; and health equity as it relates to cancer control as top-priority areas.7 Other high impact topic areas identified by the CDC for cancer planning are nutrition, physical activity, and obesity; tobacco and alcohol use; access to health services; and mental and emotional well-being.7

To address the IOM SCP recommendations and narrow the gap between guidelines and implementation, it is important to describe any disparities in receipt of SCPs and investigate how these disparities can be addressed through the tailoring of SCPs, and through community partnerships with state cancer control programs. An evaluation conducted from 2010 to 2013 reported that 38% of state or territory cancer plans addressed cancer survivorship during those years. Approximately 64% of all plans included recommendations from four public health areas: surveillance and applied research; communication, education, and training; programs, policies and infrastructure; and access to high-quality care and services.6 The CDC has prioritized projects that support receipt of appropriate care among survivors as well as meeting survivors’ psychosocial and supportive needs.

The purpose of this investigation was to describe aspects of cancer survivorship that can be summarized based on the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) cancer survivorship modules in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi, conducted in 2012 and 2014, and to describe priorities for SCPs to address disparities in the Deep South region of the United States.

Methods

Data Sources and Variables

BRFSS uses telephone surveys to collect state’s data about US noninstitutionalized residents regarding their health-related risk behaviors, including smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, diet, chronic health conditions, and use of preventive services.7 Surveys of state-based risk behaviors for chronic diseases such as cancer are used to identify gaps in healthcare delivery within states or regions.

New weighting methodology was introduced in 2012 and cellular phone–only respondents were included. Newer methodology allows stratification factors such as age, sex, categories of ethnicity, geographic regions within states, marital status, education level, home ownership, and type of telephone (landline or cellular) to reduce bias.

In an optional state module introduced in 2009, questions about cancer survivorship were introduced. Respondents were asked whether they were ever told that they had skin cancer and whether they were ever told that they had any other type of cancer. Follow-up questions included the number of cancers, type of cancer, and questions related to aspects of survivorship care. Respondents were asked about current cancer treatment, whether a summary of cancer treatment was received, whether they received instructions from a doctor for follow-up checkups and whether the instructions were written or printed, health insurance, participation in clinical trials, and physical pain from cancer or from treatment and whether any current pain was under control. For the present investigation only the cancer modules after 2012 were analyzed because of changes in survey methodology.

Variables

In addition to the data related to cancer survivorship, demographic data were collected, including sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, and age. Race was coded as five groupings: white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, other non-Hispanic, multiracial, and Hispanic. Education was categorized as less than high school, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate. Income in annual dollars was stratified as <$15,000, $15,000 to $24,999, $25,000 to $34,999, $35,000 to $49,999, and ≥$50,000.

Missing Data Imputations

For these analyses there were no imputations for missing data. Data are suppressed in the presentation if the numerator is <50 or the half-width of the confidence interval is >10. Response rates for BRFSS are calculated using standards set forth by the American Association of Public Opinion Research and found at http://www.aapor.org. For detailed information, refer to the BRFSS Summary Data Quality Reports.8,9

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics are presented as frequency data. Weighted estimates were used in the calculation of means, proportions, and confidence intervals (CIs). State-stratified prevalence odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were used to assess the relation between demographic factors (age, sex, and race/ethnicity, education, income) and SCP-related variables. Weighted logistic regression analyses incorporating the complex survey design parameters were used for unadjusted and adjusted models using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Race was dichotomized to include only white non-Hispanic and black non-Hispanic patients in modeling because of small cell frequencies in other categories. Education and income were treated as ordinal variables in the model. Because the assumption that any missing responses may not be random, a sensitivity analysis was performed to compare the results under the assumption that the missing data were not completely random.

Human Participant Compliance

The use of these data is not considered human subject research by the University of Alabama at Birmingham because it is a public use dataset and the following two criteria were met: research did not involve merging any of the datasets in such a way that individuals may be identified, and the researcher did not enhance the public dataset with identifiable or potentially identifiable data.

Results

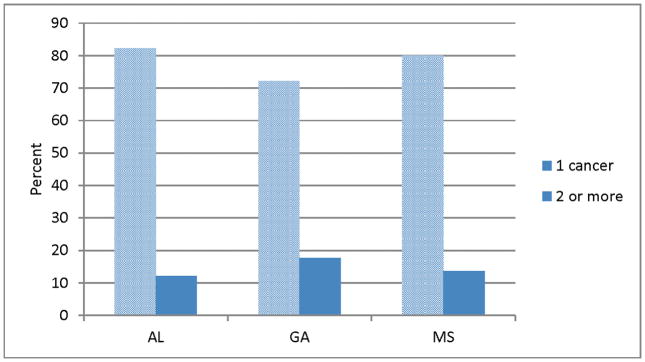

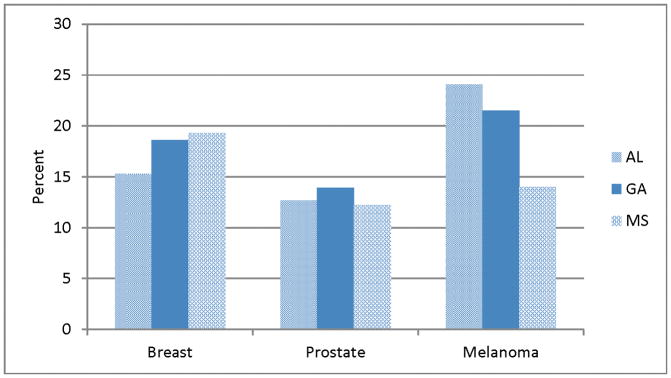

A total of 1105 participants in Alabama, 571 in Georgia, and 442 in Mississippi were available for analysis after excluding individuals who reported having nonmelanoma skin cancer. Slightly more than half of the respondents in each state were women (Table 1). The proportion aged 65 and older was 45.1% in Alabama, 42.0% in Georgia, and 51.5% in Mississippi. Black non-Hispanic survivors were 13.0% of Alabama respondents, 15.4% of Georgia respondents, and 22.8% of Mississippi respondents. The number of respondents in other racial categories was too small to report as summary frequencies. The proportion of college graduates was lowest in Alabama (17.3%), compared with 22.3% in Georgia and 19.6% in Mississippi. Across the three states, the majority reported having only one cancer diagnosed, and the most prevalent cancers were breast (female), prostate, and melanoma (Fig.).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of cancer survivors in 3 US Deep South states, BRFSS data, 2012–2014

| Characteristic | AL (2012, n = 1105) N, % (95% CI) |

GA (2012, n = 571) N, % (95% CI) |

MS (2014, n = 442) N, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 393 (45.6, 41.3–49.9) | 209 (43.3, 37.6–48.8) | 166 (45.6, 39.4–51.7) |

| Female | 712 (54.4, 50.1–58.7) | 362 (56.7, 51.2–62.3) | 276 (54.4, 48.5–60.6) |

| Age, y | |||

| 18–64 | 471 (54.8, 50.9–58.8) | 252 (58.0, 53.1–63.0) | 155 (48.5, 42.2–59.6) |

| ≥65 | 634 (45.1, 41.2–49.1) | 319 (42.0, 37.1–46.9) | 287 (51.5, 45.4–57.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White non-Hispanic | 907 (81.6, 78.2–85.0) | 460 (74.7, 69.5–79.9) | 331 (75.6, 70.4–80.8) |

| Black non-Hispanic | 144 (13.0, 10.1–15.9) | 79 (15.4, 11.5–19.3) | 104 (22.8, 17.7–27.9) |

| Other non-Hispanic | — | — | — |

| Multiracial | — | — | — |

| Hispanic | — | — | — |

| Education | |||

| <High school | 179 (20.0, 16.3–23.7) | 84 (17.8, 12.9– 22.7) | 66 (20.9, 15.0–26.8) |

| High school graduate | 363 (34.5, 30.4–38.6) | 160 (29.3, 24.1– 34.5) | 132 (28.8, 23.4–34.2) |

| Some college | 290 (28.2, 24.4–32.1) | 151 (30.6, 25.5– 35.8) | 115 (30.6, 24.9–36.4) |

| College graduate | 272 (17.3, 14.6–20.0) | 176 (22.3, 18.6– 26.0) | 127 (19.6, 15.3–23.8) |

| Income | |||

| <$15,000 | 169 (14.1, 11.1–17.2) | 72 (13.9, 9.4, 18.5) | 79 (18.7, 13.7–23.7) |

| $15,000–$24,999 | 209 (18.3, 15.1–21.7) | 101 (17.4, 13.1–21.7) | 81 (19.2, 14.0–24.4) |

| $25,000–$34,999 | 130 (13.7, 10.3–17.1) | 71 (11.6, 8.2–15.0) | 50 (9.9, 6.3–13.4) |

| $35,000–$49,999 | 139 (12.5, 9.8–15.2) | 63 (11.1, 7.8–14.4) | 55 (13.6, 9.6–17.7) |

| ≥ $50,000 | 250 (24.6, 21.1–28.0) | 180 (33.7, 28.6–38.9) | 105 (24.0, 18.7–29.1) |

| Unknown | 208 (16.7, 13.7–19.8) | 84 (12.3, 9.1–15.4) | 72 (14.7, 10.4–18.9) |

— Data suppressed because of numerator <50. AL, Alabama; BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CI, confidence interval; GA, Georgia; MS, Mississippi.

Fig.

A, Percentage of number of cancers among BRFSS survey respondents. B, Three highest prevalent cancers reported by BRFSS respondents. AL, Alabama; BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, GA, Georgia, MS, Mississippi.

Of the cancer survivors, the proportion who reported receiving a written treatment summary was 34.0 (95% CI 28.2–39.7) in Alabama, 38.3 (95% CI 31.8–44.9) in Georgia, and 44.9 (95% CI 36.8–52.9) in Mississippi (Table 2). The proportion of respondents reported receiving instructions for follow-up care in Alabama was 63.6% (95% CI 58.1–69.2), 71.7% (95% CI 66.1–77.4) in Georgia, and 70.85 (95% CI 63.3–78.4) in Mississippi. Approximately two-thirds of those who received follow-up care instructions reported that these instructions were written.

Table 2.

Survivorship characteristics of cancer survivors in 3 US Deep South states, BRFSS data, 2012–2014

| Characteristic | AL N, % (95% CI) |

GA N, % (95% CI) |

MS N, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Currently receiving treatment | |||

| Yes | 105 (10.9, 8.2–13.6) | 68 (15.1, 10.8–19.4) | 87 (20.1, 15.1–25.1) |

| Completed treatment | 606 (69.1, 64.8–73.4) | 373 (66.9, 61.6–72.2) | 270 (62.2, 56.1–68.3) |

| Refused treatment | — | — | — |

| Have not started | 156 (17.1, 13.4–20.9) | 77 (13.2, 9.4–17.0) | 60 (14.0, 10.0–18.1) |

| Do not know | — | — | — |

| Missing | — | — | — |

| Received written summary of cancer treatments | |||

| Yes | 187 (34.0, 28.2–39.7) | 144 (38.3, 31.8–44.9) | 118 (44.9, 36.8–52.9) |

| No | 362 (58.4, 52.6–64.2) | 201 (55.0, 48.3–61.7) | 127 (47.2, 39.1–55.3) |

| Do not know | 53 (7.1, 4.7–9.6) | — | — |

| Missing | — | — | — |

| Received instructions regarding cancer follow-up care | |||

| Yes | 385 (63.6, 58.1– 69.2) | 271 (71.7, 66.1–77.4) | 193(70.8, 63.3–78.4) |

| No | 206 (33.5, 28.1– 38.9) | 92 (25.3, 19.9–30.8) | 71 (27.3, 19.6–34.8) |

| Do not know | — | — | — |

| Missing | — | — | — |

| Were follow-up instructions written | |||

| Yes | 251 (64.7, 57.8,–71.5) | 181 (70.7, 64.1–77.4) | 130 (73.0, 65.4–80.3) |

| No | 101 (25.7, 19.7–31.7) | 63 (20.7, 14.8–26.6) | — |

| Do not know | — | — | — |

| Insurance for cancer treatment | |||

| Yes | 561 (94.1, 91.7–96.5) | 339 (91.7, 87.9–95.5) | 246 (88.4, 82.6–94.2) |

| No | — | — | — |

| Pain from cancer | |||

| Yes | 78 (14.8, 10.1–19.6) | — | — |

| No | 523 (84.9, 80.1–89.6) | 333 (90.4, 86.8–94.0) | 233 (79.9, 72.5–87.2) |

| Do not know | — | — | — |

| Missing | — | — | — |

— Data suppressed because of numerator <50. AL, Alabama; BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CI, confidence interval; GA, Georgia; MS, Mississippi.

Nearly all of the survey participants reported that they had insurance for cancer treatment (94.1% in Alabama, 91.7% in Georgia, and 88.4% in Mississippi.) Most respondents did not report any current pain from cancer (84.9% in Alabama, 90.4% in Georgia, and 79.9% in Mississippi), and there were no statistical differences across the three states. Of those reporting current pain, the number of respondents was too few to stratify by use of current pain medication. Most respondents reported that they did not participate in clinical trials (92.7% in Alabama, 96.2% in Georgia and 91.6% in Mississippi, data not shown).

Risk Factors for SCP Information

Table 3 shows the unadjusted risk factors for receipt of cancer survivorship written summary information and follow-up care stratified by state. Among Alabamians, those with a higher level of education and higher income were more likely to receive a written summary of cancer treatments (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–1.7 and OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1–1.6, respectively). Adults older than 65 years were less likely to receive a written summary of cancer treatments as compared with adults 65 years or younger (OR 0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.8). There were no significant differences by race or sex. The positive association between education and receipt of summary information was found for respondents in Georgia, but it was of borderline significance (P = 0.059). The inverse association for age was seen in Georgia survivors, but it was not significant. Among those who reported receiving instructions from a doctor for follow-up care, the survivors tended to have a higher level of education, have a higher income, and were younger. The receipt of written or printed instructions was associated with higher income (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–1.8) and inversely associated with age 65 years or older (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.6) in Georgia survivors.

Table 3.

Relation between risk factors and survivorship care plan characteristics

| Factor | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| AL OR (95% CI) |

GA OR (95% CI) |

MS OR (95% CI) |

|

| Receive a summary of cancer treatments | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2.1 (0.9–4.6) | 1.2 (0.6–2.5) | 2.1 (0.9– 4.7) |

| Education | 1.4 (1.1–1.7)* | 1.1 (0.8–1.4) | 1.3 (0.9–1.9) |

| Income | 1.3 (1.1–1.6)* | 1.1 (0.9–1.4) | 1.0 (0.7–1.2) |

| Age, y | |||

| <65 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| ≥65 | 0.5 (0.3 0.8)* | 0.7 (0.4–1.3) | 1.0 (0.5–1.9) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female | 0.9 (0.6–1.7) | 0.9 (0.5–1.6) | 1.2 (0.6–2.4) |

| Receive instructions from a doctor for follow-up | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 1.9 (0.9–4.3) | 1.3 (0.5–3.3) | 1.2 (0.5–3.1) |

| Education | 1.3 (1.02–1.6)* | 1.0 (1.0–1.7) | 1.2 (0.8–1.8) |

| Income | 1.3 (1.1–1.5)* | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 1.0 (0.7–1.3) |

| Age, y | |||

| <65 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| ≥65 | 0.7 (0.4–1.2) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | 1.6 (0.7–3.3) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female | 1.0 (0.6–1.7) | 0.6 (0.3–1.1) | 1.4 (0.6–3.0) |

| Were the instructions written or printed | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 2.7 (0.9–8.1) | 2.1 (0.8–5.6) | 0.7 (0.3–2.1) |

| Education | 1.1 (0.8–1.5) | 1.3 (0.8–1.7) | 0.8 (0.6–1.2) |

| Income | 1.1 (0.9–1.5) | 1.2 (1.1–1.8)* | 1.0 (0.7–1.4) |

| Age, y | |||

| <65 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| ≥65 | 0.9 (0.5–1.7) | 0.3 (0.1–0.6)* | 0.4 (0.1–1.1) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Female | 1.1 (0.6–2.1) | 0.6 (0.3–1.2) | 0.6 (0.2–1.5) |

AL, Alabama; BRFSS, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; CI, confidence interval; GA, Georgia; MS, Mississippi; OR, odds ratio.

P < 0.05.

In a multivariable analysis controlling for race, sex, and education, the factors significantly associated with the likelihood of receiving a written treatment summary in Alabama were higher income (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.0–1.7) and younger age (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.3–0.8, data not shown). In Georgia, higher income was significantly associated with receiving written instruction for follow-up care (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.0–2.0), controlling for race, sex, education, and age. In Mississippi, older survivors were less likely to receive written instructions for follow-up care (OR 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.8), controlling for race, sex, education, and income.

Sensitivity Analysis

Results of the sensitivity analysis incorporating the assumption that the responses were not missing completely at random did not show any differences in the interpretation of the results; therefore, the results are presented under the assumption that missing data were random.

Discussion

This article presents results of the cancer survivorship–optional BRFSS module among three states in the US Deep South region. We found that the receipt of a written treatment summary was lower than 50% in 2012 and 2014, despite the IOM mandates for SCPs introduced in 2009. More important, there was a positive association between receipt of treatment summaries and higher income and higher education.

Previous studies have reported that SCPs help survivors to feel more informed and make healthier diet and exercise choices, and increase the likelihood that patients will share concerns about their recovery with their healthcare team members.10 Although many studies are evaluating the relations between SCPs and health outcomes, there are barriers to the implementation of SCPs in the present healthcare system.11 Some of these barriers are the cost in time and effort to create the plan, time to develop and discuss the plan with the patient, and lack of clarity about who is responsible for production of the plan.12 As shown by the present study, many survivors do not receive needed information. The implementation of SCPs could be facilitated by the development of guidelines for plan content and the use of novel delivery methods to reduce the time required of the healthcare team to tailor and deliver the plans.

One study found that the two most preferred sources for obtaining cancer information were print media and personalized reading materials such as an SCP, whereas e-mail or the Internet was ranked fourth after meeting in person with a healthcare professional to receive information on cancer.13 Many organizations already are using computer and Internet-based tools that allow patients and healthcare providers to make more informed treatment decisions based on risk stratification. One study suggested that patients with cancer are able and willing to use a Web-based computer program that generates patient-specific survival information.14 Another study, however, evaluated e-health literacy among lung cancer survivors and found that they demonstrated low e-health literacy; higher e-health was correlated with the level of education and access to e-resources.15 A survey of cancer survivors and cancer-free subjects found that health literacy and cancer-specific literacy were not greater among the survivors compared with those who were cancer free.16 In this study the authors reported that there was an education effect and that higher literacy scores were correlated with a college education or greater compared with those with lower education levels.16A

As healthcare information is disseminated, a variety of formats should be made available and adapted to the education, age, and literacy of the recipients. Frentsos discussed the use of videos as education materials among cancer survivors, emphasizing that the use of videos does not require a high level of literacy and can be delivered via smartphone, DVD, television, or computer.17 Other authors have found that among older adult populations known to have limited health literacy, the development of specific tailored materials can improve patient understanding.18 An investigation reported that among five categories of information source use (mass media, Internet and print media, support organizations, family and friends, and healthcare providers), higher education predicted the increased use of all source categories except mass media.19

The results of our study can inform the development and dissemination of SCPs as outlined in the cancer programs standards of the Commission on Cancer.20 The current standard outlines compliance with SCPs by a gradual phase-in process: providing SCPs to ≥25% of eligible patients by the end of 2016, to ≥ 50% of eligible patients by the end of 2017, and to ≥75% of eligible patients by the end of 2018. The delivery of these plans may include an emphasis in the early implementation phase on the most common cancers. The guidelines also state that the SCP may be printed or electronic, but must be delivered within 1 year of diagnosis or no later than 6 months after completion of adjuvant therapy.

Because of impending deadlines for compliance with SCPs, some barriers to implementation, such as identification of resources and advocating for SCP use, will be addressed by institutions. Community resources may assist in meeting survivorship needs through partnerships focused on these needs. National organizations and other key partners can target resources and outreach activities to address the comprehensive needs of cancer survivors.21 The greatest challenges will be developing plans that are easy to use and contained in a format customized to survivors based on their health literacy levels. The relation between SCPs and patient outcomes should continue to be examined in light of cancer survivors’ socioeconomic status and age.

A limitation of our study is that the BRFSS survivorship module includes only adults with prevalent cancers and not newly diagnosed cases. As such, the answers to the optional module reflect this distribution of cancer cases and may not be representative of the cancer experience of the general population. Also, the BRFSS is a based on self-reporting and as such there may be some recall bias and possible misclassification of response data. Some data were suppressed in presentation in this investigation because of the small numbers.

Conclusions

Addressing the gaps identified between SCP development and delivery to survivors is important given the evidence of disparities in the receipt of SCPs across survivor age, education, and income in the US Deep South region.

Key Points.

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System survivorship module includes questions about current cancer treatment, whether a summary of cancer treatment was received, whether the survivor received instructions from a doctor for follow-up check-ups and whether the instructions were written or printed, health insurance for cancer treatment, participation in clinical trials, current physical pain from cancer or treatment, and whether any current pain was under control.

The receipt of a written treatment summary was lower than 50% in 2012 and 2014, despite the Institute of Medicine mandates introduced in 2009.

A positive association was found between receipt of treatment summaries and higher income and higher education. Adults older than 65 years were less likely compared with younger adults to receive a written summary of cancer treatments.

These findings suggest that older survivors with a lower socioeconomic status as indexed by education and income were less likely to receive survivorship care plans; addressing this disparity is critical to the care and follow-up of these survivors.

Acknowledgments

R.A.D. and B.E.J. are supported by National Cancer Institute grant no. P30CA13148.

Footnotes

“In this study” was interpreted to mean reference 16 and the citation was added to text. Please confirm this clarification is correct.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute.

J.W.W. did not report any financial relationships or conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. [Accessed December 22, 2016];Cancer treatment and survivorship facts and figures 2014–2015. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-042801.pdf.

- 2.Institute of Medicine. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fashoyin-Aje LA, Martinez KA, Dy SM. New patient-centered care standards from the Commission on Cancer: opportunities and challenges. J Support Oncol. 2012;10:107–111. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blanch-Hartigan D, Forsythe LP, Alfano CM, et al. Provision and discussion of survivorship care plans among cancer survivors: results of a nationally representative survey of oncologists and primary care physicians. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1578–1585. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.7540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birken SA, Deal AM, Mayer DK, et al. Determinants of survivorship care plan use in US cancer programs. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:720–727. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0645-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Underwood JM, Lakhani N, Rohan E, et al. An evaluation of cancer survivorship activities across national comprehensive cancer control programs. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:554–559. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0432-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed December 22, 2016];Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey data. https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_data.htm.

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed December 22, 2016];Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2012 summary data quality report. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2012/pdf/summarydataqualityreport2012_20130712.pdf. Published July 3, 2013.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed December 22, 2016];Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System 2014 summary data quality report. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2014/pdf/2014_dqr.pdf. Published July 29, 2015.

- 10.Hill-Kayser CE, Vachani CC, Hampshire MK, et al. Impact of internet-based cancer survivorship care plans on health care and lifestyle behaviors. Cancer. 2013;119:3854–3860. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nicolaije KA, Ezendam NP, Vos MC, et al. Oncology providers’ evaluation of the use of an automatically generated cancer survivorship care plan: longitudinal results from the ROGY Care trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:248–259. doi: 10.1007/s11764-013-0327-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salz T, Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS, et al. Survivorship care plans in research and practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:101–117. doi: 10.3322/caac.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Playdon M, Ferrucci LM, McCorkle R, et al. Health information needs and preferences in relation to survivorship care plans of long-term cancer survivors in the American Cancer Society’s Study of Cancer Survivors: I. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10:674–685. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0513-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Solowski NL, Okuyemi OT, Kallogjeri D, et al. Patient and physician views on providing cancer patient-specific survival information. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:429–435. doi: 10.1002/lary.24007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Milne RA, Puts MT, Papadakos J, et al. Predictors of high eHealth literacy in primary lung cancer survivors. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30:685–692. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0744-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkins WD, Zahnd WE, Spenner A, et al. Comparison of cancer-specific and general health literacy assessments in an educated population: correlations and modifying factors. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31:268–271. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0816-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frentsos JM. Use of videos as supplemental education tools across the cancer trajectory. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2015;19:E126–E130. doi: 10.1188/15.CJON.E126-E130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jewitt N, Hope AJ, Milne R, et al. Development and evaluation of patient education materials for elderly lung cancer patients. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31:70–74. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0780-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blanch-Hartigan D, Viswanath K. Socioeconomic and sociodemographic predictors of cancer-related information sources used by cancer survivors. J Health Commun. 2015;20:204–210. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2014.921742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American College of Surgeons. [Accessed December 22, 2016];Cancer program standards: ensuring patient-centered care. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/coc/standards. Published 2016.

- 21.Fairley TL, Pollack LA, Moore AR, et al. Addressing cancer survivorship through public health: an update from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2009;18:1525–1531. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2009.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]