Abstract

Interest in nephrology has been declining in recent years. Long work hours and a poor work/life balance may be partially responsible, and may also affect a fellowship’s educational mission. We surveyed nephrology program directors using a web-based survey in order to define current clinical and educational practice patterns and identify areas for improvement. Our survey explored fellowship program demographics, fellows’ workload, call structure, and education. Program directors were asked to estimate the average and maximum number of patients on each of their inpatient services, the number of patients seen by fellows in clinic, and to provide details regarding their overnight and weekend call. In addition, we asked about number of and composition of didactic conferences. Sixty-eight out of 148 program directors responded to the survey (46%). The average number of fellows per program was approximately seven. The busiest inpatient services had a mean of 21.5±5.9 patients on average and 33.8±10.7 at their maximum. The second busiest services had an average and maximum of 15.6±6.0 and 24.5±10.8 patients, respectively. Transplant-only services had fewer patients than other service compositions. A minority of services (14.5%) employed physician extenders. Fellows most commonly see patients during a single weekly continuity clinic, with a typical fellow-to-faculty ratio of 2:1. The majority of programs do not alter outpatient responsibilities during inpatient service time. Most programs (approximately 75%) divided overnight and weekend call responsibilities equally between first year and more senior fellows. Educational practices varied widely between programs. Our survey underscores the large variety in workload, practice patterns, and didactics at different institutions and provides a framework to help improve the service/education balance in nephrology fellowships.

Keywords: nephrology fellowship, education, survey, demography, faculty, fellowships and scholarships, humans, inpatients, internet, minority groups, nephrology, outpatients, physician assistants, religious missions, surveys and questionnaires, United States, workload

Introduction

The past several years have seen declining interest in nephrology among medical residents despite an increase in United States medical and osteopathic graduates (1). Over the last 7 years, the number of nephrology applicants per position through the National Resident Matching Program has decreased from 1.5 to 0.60—a 60% decline (1). Accompanying this has been a dramatic increase in the number of unfilled programs (16% in 2011 versus 58.3% in 2016) and positions (9.2% in 2011 versus 36.8% in 2016) (1). Nephrology is particularly unpopular among United States medical graduates. Since 2009, the number of United States medical graduates entering nephrology has declined by 46%, and in the 2016 match they accounted for only 17.4% of incoming fellows (1,2).

The cause of this decrease is likely multifactorial. Surveys show the most prominent reasons trainees do not enter nephrology relate to workforce issues (long work hours, a poor life/work balance, an overwhelming and unpredictable workload, and stressful on call experiences) and patient factors (medical complexity and behavioral issues) (3,4). When trainees do enter nephrology, many of them are less than “extremely” or “very” satisfied with their selection, including approximately 10% who are frankly dissatisfied (5). Distressingly, nearly 20% of graduating nephrology fellows regret choosing nephrology, and approximately one quarter noted poor teaching and mentoring by faculty and an overall poor experience during fellowship (5,6).

Recently there has been more focus on striking the right balance between service and education for physicians in training (7). Although medical education relies on learning in the context of providing clinical service to patients, overemphasis on clinical service at the expense of other educational opportunities may be detrimental (7). Studies among residents have shown that a heavy workload negatively correlates with learning (8,9). In addition, fatigue and burnout are prominent concerns among physicians in training (10,11). These issues have received significant attention in residency programs, with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) instituting substantial regulations in 2003 and 2011 (12). Fellowships, however, have not received as much attention.

In light of the declining interest in nephrology, the perceived dissatisfaction with workload and training deserves attention. With our commitment to providing excellent care to the millions of patients suffering from kidney disease, it is important to ensure enough future nephrologists to meet ongoing clinical needs. We surveyed nephrology program directors to define the landscape of current nephrology training to identify areas ripe for improvement and innovation.

Materials and Methods

We conducted a web-based survey of nephrology program directors using surveymonkey.com (Palo Alto, CA). The survey was emailed to program directors of all ACGME-approved adult nephrology fellowship programs. The survey was developed by one nephrology fellow and three academic nephrologists with significant clinical and administrative roles in the fellowship. The survey was pilot tested by a group of academic nephrologists at our institution for content validity and operational characteristics. We constructed questions on the basis of recurrent themes in surveys of both nephrology and internal medicine (IM) trainees. Questions captured program demographics and addressed fellows’ experiences in three domains: clinical workload (inpatient and outpatient), call responsibilities, and education. The program directors were asked to designate one service as primary. This labeling allowed for correlation of service characteristics with a particular service. This designation was left to the discretion of the program director, and did not always correspond to the busiest service. Busiest and second busiest services were identified post hoc as the services with the highest and second highest mean number of patients, respectively. There was no input from commercial or industry sources and no incentive was offered to respondents.

At the time of the survey, 148 nephrology training programs were recognized by the ACGME. Approximately 1 week before the start of the study, we emailed program directors informing them of the survey, outlining its intent. Two weeks after survey distribution, we followed up with the whole cohort thanking them for their participation if they completed the survey and reminding them if they did not. Subsequent nonrespondents were sent one additional reminder. All responses were kept confidential and no personally identifiable information was included. Data were stored on the surveymonkey.com website on a password-protected account. Data were summarized as mean (SD) or percentages. The survey was reviewed and approved by the University of Rochester Institutional Review Board.

Results

Sixty-eight program directors (46%) responded to the survey.

Demographics of the Program

The average number of fellows per program was approximately seven, (range three to >12). Most programs (78%) were 2 years in length, with the remainder offering 1 or more additional research years. Most program directors responding were from the Northeast (35%), followed by the Midwest (28%), the South (26%), and the West (11%).

Inpatient Service Characteristics.

Inpatient Responsibilities.

The number of fellow-covered services in each program varies from one to five. First year fellows typically cover service more frequently than more senior fellows. In 68% of programs first year fellows cover ≥7 months of service with 21% requiring 10–12 months (see Supplemental Material).

Structure and Coverage of Inpatient Services.

Fifty-three programs provided details about 177 separate inpatient services. A third of the services are general nephrology (excluding transplant and ESRD patients), 28% are a mixed population (any type of nephrology patient without limitation), 21% are transplant, 15% are ESRD, and 3% are intensive care unit patients. Almost all (>90%) services are covered by one fellow and one faculty member. Each program director was asked to designate one service as primary. The vast majority of these (not always the busiest services) have residents (86.8%), whereas less than half (42.5%) of the nonprimary services do. Physician extenders are employed by 14.5% of services.

Patient Censuses and Workload.

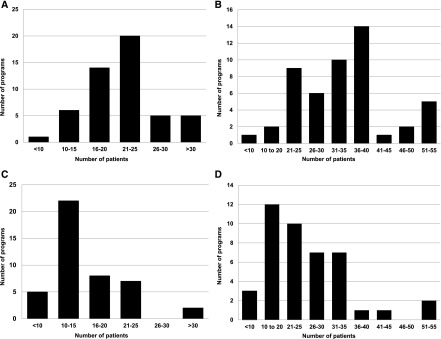

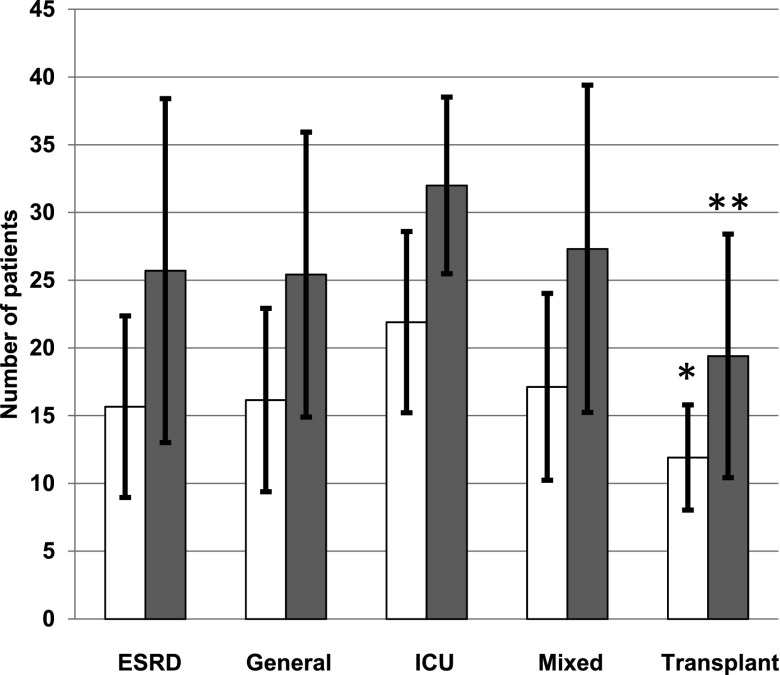

The busiest services averaged 21.5±5.9 patients, with a mean maximum of 33.8±10.7 (Figure 1, A and B), whereas for the second busiest services the values are 15.6±6.0 and 24.5±10.8, respectively (Figure 1, C and D). As most services are covered by one fellow, the mean and maximum numbers of patients per fellow were slightly, but not significantly, lower than the aforementioned values. The average and maximum number of patients on general nephrology, ESRD, transplant, intensive care unit, and mixed services are shown in Figure 2. Transplant services had significantly fewer patients (both average and maximum) when compared with any other service (P<0.05 for all comparisons). In about three quarters of the programs, there is no cap on census (76.9%) or number of notes written by fellows (72.2%). The maximum number of patients a single fellow was expected to cover on a single day varied widely between services from ten to >50 (not including resident contributions).

Figure 1.

Census characteristics of busiest and second busiest services. Distribution of mean number of patients on average and at their maximum for the busiest (A and B) and second busiest (C and D) services.

Figure 2.

Census characteristics of different services based on intended patient population. Mean (±SD) number of patients on average (white bars) and at their maximum (gray bars) for different intended service populations. *P=0.01 versus ESRD, P=0.001 versus general, P<0.001 versus ICU, P=0.001 versus mixed; **P=0.03 versus ESRD, P=0.001 versus general, P=0.01 versus ICU, P=0.002 versus mixed. ICU, intensive care unit.

Call Responsibilities.

About three quarters of programs divide overnight call responsibilities equally across all years. A smaller number of programs require first year fellows to do more (17%) or all (7.6%) of the overnight call. One program employed a night float system. The vast majority of programs assign call on a nightly basis (84.9%), although some use an alternative schedule—typically weekly (13.2%). In all programs surveyed save one, fellows take call from home. Approximately two thirds of the programs’ call responsibilities are at a single hospital. The amount of calls covered in a 3-month period ranged from 1–3 to >15 nights (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Night and weekend call responsibilities. Average number of night (A) and weekend (B) calls covered by a single fellow over a 3-month period.

Responsibility for weekend call is similar—in 73.6% of programs it is divided equally across all years. The remainder requires first years to do more (22.6%) or all (3.8%) of the weekend call. The structure of weekend call was varied. Most commonly one fellow covers Friday night through Monday morning (43.4%), although there were a variety of configurations. Over a 3-month period, the average number of calls covered by a single fellow ranged from 1 to >6 weekends (Figure 3B).

Outpatient Clinical Responsibilities.

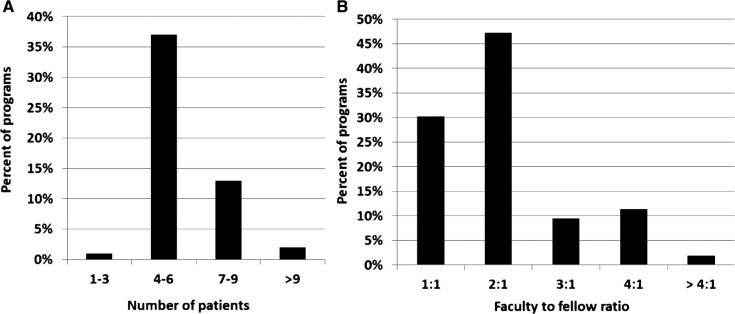

Most programs (85.9%) require fellows to have one half day continuity clinic per week, with the rest requiring two. Most fellows see four to six patients during each clinic, with a range of one to three to more than nine (Figure 4A). The most common fellow-to-faculty ratio for fellows’ continuity clinic is 2:1 (47.2%). Almost a third are 1:1 (30.2%) and the remainder have higher ratios (Figure 4B). Most programs (73.6%) do not alter clinic schedule when the fellow has inpatient responsibilities. Some programs will abbreviate the schedule (17.0%), and in one program the fellow does not attend clinic while on inpatient service. Some program directors noted that the fellows may receive concessions on the inpatient service on a clinic day.

Figure 4.

Outpatient continuity clinic characteristics. Number of patients (A) and fellow-to-faculty ratio (B) for a typical fellows’ continuity clinic session.

Educational Content.

Specifics of the educational practices including time spent and number and structure of conferences differed widely between programs. The most frequent activities include didactic lectures, journal club, case conference, and specialty grand rounds, with many programs holding these on a weekly basis. All programs incorporate research and pathology conferences, most commonly on a monthly basis. Activities such as continuous quality initiative and morbidity and mortality conferences receive less emphasis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Scope and frequency of educational conferences offered by fellowship programs

| Conference | Never | Weekly | Every 2 Weeks | Monthly | Every 2 Months | Quarterly | Semiannually | Annually |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Journal club | 0 | 38 | 11 | 45 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Subspecialty grand rounds/City-wide conference | 6 | 47 | 0 | 20 | 4 | 16 | 6 | 2 |

| Case conference | 4 | 53 | 15 | 23 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| M&M conference | 14 | 8 | 6 | 27 | 2 | 31 | 12 | 0 |

| Research conference | 0 | 13 | 17 | 37 | 4 | 15 | 10 | 4 |

| CQI conference | 14 | 4 | 0 | 27 | 6 | 20 | 22 | 8 |

| Didactic lecture on core topic | 0 | 81 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Pathology conference | 0 | 13 | 17 | 55 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 0 |

Data are presented as %. M&M, Morbidity and Mortality; CQI, Continuous Quality Improvement.

Discussion

Our survey uncovers several points that deserve attention and demonstrates the variability in many areas of fellowship training.

We found that at their busiest, fellows may be covering >50 patients at one time. Heavy service loads have several implications. Long work hours are of considerable concern to nephrology trainees, and lead to dissatisfaction (5,13). Although we did not explore nuances of what contributes to long work hours, heavy patient loads are likely an important factor.

Heavy service loads may also affect nephrology recruitment. Trainees cite long work hours as a common reason not to enter nephrology (3). How residents perceive fellows and faculty may influence their decision to enter the field. An unhappy, stressed, and over-worked fellow may dissuade prospective applicants. Discouragingly, almost 30% of current fellows would not recommend nephrology to medical students and residents (13).

Addressing the burden of a heavy workload may attract more residents into nephrology. In this endeavor, we can learn from our IM colleagues. Over the last decade many residency programs have implemented measures to strike a balance between service and education. Perhaps we may achieve a good service/education balance and prevent burnout among nephrology fellows by adopting some of the ideas discussed below.

Our survey shows that most programs do not cap the number of patients covered by a single fellow. Within IM residency programs, census caps simultaneously improve trainees’ perception of workload and increase conference attendance (9). These benefits need to be balanced against preparing fellows for “real life practice.” A fellow faced with a large census develops important skills of efficiency and prioritization—which may be lost with capitation. In addition, a reasonable clinical workload for a nephrology fellow is not clear, and likely depends upon level of training and the complexity of the service. Furthermore, a fellow census cap would likely increase faculty workload, reducing opportunities for education and mentoring.

We found that only a minority of services use physician extenders. Increased physician extender use would decrease the fellows’ total patient load, allowing more attention to patients of higher educational value. Alternatively, faculty may see more patients without fellow assistance, but the acceptability of this would need to be discussed at an institutional level.

Most programs do not adjust fellows’ continuity clinic responsibilities while on inpatient service. This may impart extra stress to fellows already burdened by a heavy inpatient census. In addition, clinics during inpatient rotations may decrease the educational value of both. Some residencies use a block model in which continuity clinic is scheduled during noninpatient service weeks (14). Studies in IM residencies show that this model decreases stress and fragmentation of inpatient care, reduces interruptions in clinic, and improves the educational value of the ambulatory experience (15,16). Drawbacks include disruption of elective and/or research time and potential loss of continuity in the ambulatory setting. Programs would still have to meet the ACGME requirements of averaging a half day of clinic per week and not interrupting continuity clinic for more than a month (17).

Weekend and overnight call are a concern for most fellows (13). The majority of programs divide night call among fellows who still have daytime duties. Strategies to lessen the burden of call, without compromising patient care, would undoubtedly be welcomed by fellows. One program surveyed uses a night float system, although this may not be feasible for all. Another strategy is to address unnecessary calls. Our institutional audit found that for 27% of after-hour pages no action was taken (18). Eliminating these calls would help reduce the call burden without compromising patient care.

How have other specialties addressed recruiting residents into their programs? Pulmonary critical care medicine (PCCM) fellowships are historically very popular among IM trainees, with fill rates of >95% since 2006 (2,19). Surveys show that for PCCM, more exposure to the field, the presence of PCCM role models, and encouragement to join the field by either faculty or current fellows are associated with serious consideration of PCCM (20). The presence of role models is particularly relevant, as about a third of residents surveyed state that the lack of mentorship is one reason they eschew nephrology (6). Many residents are enticed by the procedural aspects of PCCM—the paucity of which may discourage residents from consideration of nephrology (3,20). Kalloo et al. (21) argue that formal incorporation of interventional nephrology with its myriad of procedures would help attract more applicants. Some of the more commonly cited reasons toward consideration of a career in PCCM—intellectual stimulation, treating acutely, critically ill patients, and the application of challenging physiology—seem perfectly aligned with what nephrology has to offer, and we need to stress this to trainees. Common factors dissuading residents from pursuing PCCM are similar to those noted by residents and current nephrology fellows, including work/life balance (20).

We can also learn from our colleagues who share our difficulty in recruiting. Infectious disease (ID) programs filled just 65% of their spots in 2016, the lowest level in 5 years (2). A recent study looking at predictors of choosing an ID fellowship found that case-based learning, a nonmemorization pedagogy, and having the preclinical ID topics taught by ID faculty rather than basic science faculty was associated with increased interest in ID as a career (22). Perhaps we can incorporate some or all of these ideas at our own institutions. In addition, some within the ID community propose that a career combining ID and critical care medicine may attract more interest in ID training (23). A similar concept of nephrology/critical care medicine is an exciting opportunity to increase interest in our field and bears further consideration, particularly given the popularity of PCCM.

Our survey has some limitations. We had a 46% response rate, thus nonresponse bias may be an issue. We chose to survey program directors—perhaps we would have received different answers had we surveyed the fellows instead. We likely did not obtain all relevant information with our survey instrument. With respect to work practices we equated “busyness” with number of patients. This supposition may not hold if patient populations differ substantially between services and/or institutions, or if fellows spend different amounts of time on procedural aspects of nephrology. Recall bias may also be an issue with respect to the average and maximum numbers of patients on each service as directors may preferentially remember when the services were very busy. Finally, our survey was largely conducted before the most recent match and may not reflect changes in service structures and strategies to cover services (for example the use of physician extenders) since that time.

Our survey highlights the current state of nephrology training in the United States. We found that many programs are struggling with high patient volumes, and we are concerned that this may affect the number of trainees entering nephrology. We discuss several potential interventions which may ameliorate large service loads and increase the desirability of our specialty. With continued declining interest, ensuring a good experience during training such that fellows positively represent and recommend nephrology to residents and medical students is crucial.

Disclosures

S.E.L. has served as a consultant for Relypsa, Inc. (Santa Clara, CA). C.A.M. serves as the nephrology section editor for VisualDx (Rochester, NY).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

S.E.L. acknowledges support from the Ritchie Educational Award.

Part of this work was presented in abstract form at American Society of Nephrology’s Kidney Week in San Diego, California, November 3–8, 2015.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.06530616/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pivert K: NRMP SMS Nephrology Match for Appointment Year 2016–2017: ASN Brief Analysis, 2015. Available at: https://www.asn-online.org/education/training/workforce/ASN_NRMP_SMS_2016_Analysis.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2016

- 2.Results and Data Specialties Matching Service, 2016. Available at: http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/Results-and-Data-SMS-2016_Final.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2016

- 3.Jhaveri KD, Sparks MA, Shah HH, Khan S, Chawla A, Desai T, Iglesia E, Ferris M, Parker MG, Kohan DE: Why not nephrology? A survey of US internal medicine subspecialty fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 61: 540–546, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane CA, Brown MA: Nephrology: A specialty in need of resuscitation? Kidney Int 76: 594–596, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah HH, Jhaveri KD, Sparks MA, Mattana J: Career choice selection and satisfaction among US adult nephrology fellows. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1513–1520, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torri D, Sparks M, Calderon K, Shah H, Jhaveri KD: Life after renal fellowship: Survey results. ASN Kidney News 3: 6, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haney EM, Nicolaidis C, Hunter A, Chan BKS, Cooney TG, Bowen JL: Relationship between resident workload and self-perceived learning on inpatient medicine wards: A longitudinal study. BMC Med Educ 6: 35, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haferbecker D, Fakeye O, Medina SP, Fieldston ES: Perceptions of educational experience and inpatient workload among pediatric residents. Hosp Pediatr 3: 276–284, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thanarajasingam U, McDonald FS, Halvorsen AJ, Naessens JM, Cabanela RL, Johnson MG, Daniels PR, Williams AW, Reed DA: Service census caps and unit-based admissions: Resident workload, conference attendance, duty hour compliance, and patient safety. Mayo Clin Proc 87: 320–327, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Block L, Wu AW, Feldman L, Yeh H-C, Desai SV: Residency schedule, burnout and patient care among first-year residents. Postgrad Med J 89: 495–500, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elmariah H, Thomas S, Boggan JC, Zaas A, Bae J: The burden of burnout: An assessment of burnout among internal medicine residents after the 2011 duty hour changes [published online ahead of print February 25, 2016]. Am J Med Qual [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resident Duty Hours in the Learning and Working Environment Comparison of 2003 and 2011 Standards. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/dh-ComparisonTable2003v2011.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2016

- 13.Masselink L, Salsberg E, Wiu X, Quigley L, Collins A: Report on the 2015 Survey of Nephrology Fellows. Available at: https://www.asn-online.org/education/training/workforce/Nephrology_Fellow_Survey_Report_2015.pdf. Accessed June 9, 2016

- 14.Warm EJ, Schauer DP, Diers T, Mathis BR, Neirouz Y, Boex JR, Rouan GW: The ambulatory long-block: An accreditation council for graduate medical education (ACGME) educational innovations project (EIP). J Gen Intern Med 23: 921–926, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaudhry SI, Balwan S, Friedman KA, Sunday S, Chaudhry B, Dimisa D, Fornari A: Moving forward in GME reform: A 4 + 1 model of resident ambulatory training. J Gen Intern Med 28: 1100–1104, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mariotti JL, Shalaby M, Fitzgibbons JP: The 4:1 schedule: A novel template for internal medicine residencies. J Grad Med Educ 2: 541–547, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Nephrology (Internal Medicine): 2016. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/148_nephrology_int_med_2016.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2016

- 18.Sandal S, Singh J, Liebman SE: Prospective analysis of after-hour pages to nephrology fellows. Am J Kidney Dis 64: 158–159, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Results and Data Specialties Matching Service, 2010. Available at: http://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/resultsanddatasms2010.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2016

- 20.Lorin S, Heffner J, Carson S: Attitudes and perceptions of internal medicine residents regarding pulmonary and critical care subspecialty training. Chest 127: 630–636, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalloo SD, Mathew RO, Asif A: Is nephrology specialty at risk? Kidney Int 90: 31–33, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bonura EM, Lee ES, Ramsey K, Armstrong WS: Factors influencing internal medicine resident choice of infectious diseases or other specialties: A National Cross-sectional Study. Clin Infect Dis 63: 155–163, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadri SS, Rhee C, Fortna GS, O’Grady NP: Critical care medicine and infectious diseases: An emerging combined subspecialty in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 61: 609–614, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.