Abstract

Background and objectives

Little is known about the relation between the content of advance directives and downstream treatment decisions among patients receiving maintenance dialysis. In this study, we determined the prevalence of advance directives specifying treatment limitations and/or surrogate decision-makers in the last year of life and their association with end-of-life care among nursing home residents.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Using national data from 2006 to 2007, we compared the content of advance directives among 30,716 nursing home residents receiving dialysis to 30,825 nursing home residents with other serious illnesses during the year before death. Among patients receiving dialysis, we linked the content of advance directives to Medicare claims to ascertain site of death and treatment intensity in the last month of life.

Results

In the last year of life, 36% of nursing home residents receiving dialysis had a treatment-limiting directive, 22% had a surrogate decision-maker, and 13% had both in adjusted analyses. These estimates were 13%–27%, 5%–11%, and 6%–13% lower, respectively, than for decedents with other serious illnesses. For patients receiving dialysis who had both a treatment-limiting directive and surrogate decision-maker, the adjusted frequency of hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, intensive procedures, and inpatient death were lower by 13%, 17%, 13%, and 14%, respectively, and hospice use and dialysis discontinuation were 5% and 7% higher compared with patients receiving dialysis lacking both components.

Conclusions

Among nursing home residents receiving dialysis, treatment-limiting directives and surrogates were associated with fewer intensive interventions and inpatient deaths, but were in place much less often than for nursing home residents with other serious illnesses.

Keywords: dialysis; ESRD; advance directives; hospice care; hospices; hospitalization; humans; inpatients; intensive care units; kidney failure, chronic; Medicare; nursing homes; prevalence; renal dialysis; terminal care; United States

Introduction

More than 80,000 Americans die each year while receiving maintenance dialysis therapy for ESRD (1). Although dialysis can sustain life, it rarely restores health or independence. Surveys suggest that a majority of patients receiving dialysis would prefer care focused on maintaining comfort rather than prolonging life if they were to become seriously ill (2–4). Yet many patients with ESRD receive treatments near the end of life that are aimed at prolonging life rather than maximizing comfort, and family members rate the quality of death for patients with ESRD lower than for other serious illnesses (5,6).

Advance directives are often promoted for patients with serious illness such as ESRD as a means to avoid interventions that are unwanted or of limited benefit. Although recommended in practice guidelines (7), available data suggest that only one in three patients with ESRD has completed an advance directive (8–10). It is unclear whether the low prevalence of advance directives in this population reflects lack of engagement in advance care planning or patient preferences for aggressive care (2). Because of uncertainty about the reasons for low use of advance directives and a lack of compelling data regarding their effectiveness in this population, efforts to expand advance care planning among patients with ESRD have not gained traction.

We sought to address these knowledge gaps by studying nursing home residents who are receiving maintenance dialysis. More than one third of Medicare beneficiaries with ESRD reside in a nursing home near the end of life. Among nursing home residents without ESRD, two thirds have an advance directive and more than half have a treatment-limiting advance directive (11). Although it is recognized that nursing home residents with ESRD have limited life expectancy (12), it is not known how frequently they complete advance directives requesting treatment limitations or naming a surrogate.

We used a national registry of nursing home residents linked to Medicare claims to determine (1) the content of advance directives that were in place near the end of life among nursing home residents receiving dialysis versus patients with other serious illnesses; (2) among patients with ESRD, whether having a treatment-limiting directive and surrogate decision-maker were associated with less intensive end-of-life care; and (3) how often patients with ESRD who had a treatment-limiting directive received care that was consistent with their advance directive.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

We used data from the United States Renal Data System (USRDS), a national registry of patients with ESRD, linked to Medicare claims and the Minimum Data Set (MDS). The MDS is part of the federally-mandated process for clinical assessment of all residents in Medicare- and Medicaid-certified long-term care facilities, and includes documentation of the presence and content of advance directives. The study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board and Research Committee at Stanford University and the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto.

Of the 156,533 patients who received dialysis for >90 days and died between 2006 and 2007, 97,226 had continuous Medicare Part A&B coverage in the last 6 months of life. Of these patients, we identified 30,716 patients with at least one record in the MDS between 31 and 365 days before death and a response to at least one of the MDS items assessing the presence or absence of an advance directive.

For comparative purposes, we included a cohort of non-ESRD nursing home decedents. From a random 10% sample of patients in the MDS we identified 87,830 patients without ESRD who died between the years 2006 and 2007 and had a nonmissing advance directive assessment between 31 and 365 days before death. From this sample, we identified three mutually exclusive groups with a serious illness in hierarchic fashion: patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy (n=2286), patients with oxygen- or ventilator-dependent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (n=17,560), and patients with advanced dementia (n=10,979) (see Supplemental Appendix for methods and cohort characteristics in Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of nursing home residents with ESRD, cancer, advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and advanced dementia in the year before death

| Characteristic | ESRD (n=30,716) | Cancer Receiving Chemotherapy or Radiation (n=2286) | Advanced COPD (n=17,560) | Advanced Dementia (n=10,979) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 72±12 | 79±10 | 82±9 | 86±9 |

| Time from nursing home admission, m | 7 (4, 11) | 8 (4, 11) | 9 (5, 12) | 11 (9, 12) |

| Women, % | 51 | 60 | 60 | 73 |

| Race, % | ||||

| White | 67 | 88 | 93 | 86 |

| Black | 29 | 11 | 6 | 12 |

| Other | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Cancer receiving chemotherapy or radiation, % | 1 | 100 | — | — |

| Advanced COPD, % | 19 | 23 | 100 | 7 |

| Advanced dementia, % | 2 | 5 | — | 100 |

| Impaired decision-making skills, % | 30 | 35 | 40 | 99 |

| Activities of Daily Living scorea | 17±7 | 16±7 | 16±7 | 25±4 |

Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD, or median (interquartile range), as appropriate. Conditions were identified hierarchically, starting with ESRD, followed by cancer, dementia, and COPD. —, not applicable.

The Activities of Daily Living score ranges from 0 to 28; higher scores indicate more functional limitations.

Treatment-Limiting Directives and Surrogate Decision-Makers

MDS assessments are completed by health care professionals at admission to a nursing home and quarterly thereafter. For these analyses, we used the last available patient assessment between 31 and 365 days before death. MDS assessments have been demonstrated to have high reliability (13). Respondents recorded whether there was documentation in the patient’s medical record of a living will, a surrogate decision-maker, and for each of the following treatment limitations: “do not resuscitate,” “do not hospitalize,” feeding restrictions, medication restrictions, and other treatment restrictions. We considered patients to have some form of advance directive if they had documentation of a living will, a surrogate decision-maker for health care, or a treatment limitation. We further categorized patients according to the presence or absence of a directive specifying treatment limitations, and according to the presence or absence of a surrogate decision-maker. All patients had complete data for the “do not resuscitate” item but could be missing information on other treatment limitations and/or presence of a surrogate decision-maker. These patients were categorized as lacking the respective treatment limitation and lacking a surrogate decision-maker.

End-of-Life Health Care

For patients with ESRD, we ascertained hospitalization in the last month of life, utilization of hospice, and death in the hospital using Medicare Part A claims. We ascertained intensive care unit (ICU) admission and use of the following intensive procedures in the last month of life with International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) procedure codes and revenue codes: cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), intubation and mechanical ventilation, and placement of a gastrostomy tube (Supplemental Table 1). We ascertained discontinuation of dialysis before death from the ESRD Death Notification Form.

Covariates

We recorded age, sex, race, and years receiving dialysis from the USRDS Patients File and most recent dialysis modality before death from the Treatment History File. We searched all Medicare Part A and Part B claims for a year predating the month before death to ascertain chronic conditions using ICD-9 diagnosis codes. We used the nursing facility entry date to calculate the number of months from admission to the nursing home to death. We used the last available MDS assessment to record the patient’s cognitive and functional status between 31 and 365 days before death. We recorded patients’ decision-making skills using a single item on the MDS and their functional status using the MDS Activities of Daily Living scale ranging from 0 to 28 points, with higher scores indicating more extensive functional impairment (13). To account for regional differences, we assigned patients to hospital referral regions on the basis of their zip code. We characterized hospital referral regions into quintiles of average Medicare spending per decedent in the last 2 years of life, as reported by the Dartmouth Atlas of Healthcare for the year 2007 (14).

Statistical Analyses

We determined the age-, sex-, and race-adjusted prevalence of advance directives and each component thereof in the year before death for patients with ESRD, cancer, advanced COPD, and advanced dementia using modified Poisson regression models (15).

We compared the characteristics of patients with ESRD according to the presence or absence of a treatment-limiting directive and surrogate decision-maker. We then tabulated the proportion of patients who underwent intensive treatments in the last month of life. For each utilization measure, we estimated the adjusted risk difference (and 95% confidence interval) between the referent group of patients without a treatment-limiting directive or surrogate decision-maker and those with documentation of one or both of these components, using modified Poisson regression models. Adjusted models accounted for correlation of patients within nursing home facilities through cluster-robust SEMs, and included age, sex, race, duration of dialysis, length of time since nursing home admission, number of days hospitalized in the prior year, hospital referral region spending quintile, functional status, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, stroke, chronic liver disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, depression, dementia, and impaired decision-making skills. In sensitivity analyses, we matched patients on their propensity to have a treatment-limiting directive and a surrogate (Supplemental Appendix). Because there was evidence of a statistical interaction between treatment-limiting directive and a surrogate decision-maker for most outcomes, we also conducted analyses stratified by both variables.

Finally, we estimated the proportion of patients who received a treatment in the last month of life that was discordant with what was specified in their treatment-limiting directive. We defined an intervention as being discordant with the treatment-limiting directive if patients with a “do not resuscitate” directive received CPR or mechanical ventilation, if patients with a “do not hospitalize” directive were hospitalized, or if patients with feeding restrictions received a gastrostomy tube. We used modified Poisson regression to determine the association between a surrogate decision-maker and other clinical characteristics with the risk of receiving discordant treatment. The analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 and StataMP v13.

Results

Advance Directives among Patients with ESRD versus Other Serious Illnesses

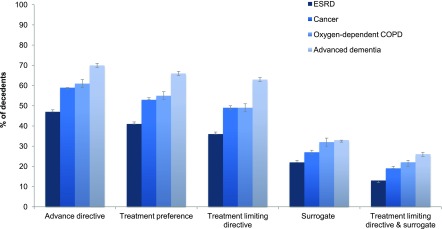

The age-, sex-, and race-adjusted prevalence of advance directives was 47% among nursing home residents with ESRD, 59% among patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy or radiation therapy, 61% among patients with advanced COPD, and 70% among patients with advanced dementia, respectively (Figure 1). The prevalence of each advance directive component was lower among patients with ESRD than for patients with other serious illnesses. For example, the adjusted prevalence of an advance directive indicating a treatment limitation and a surrogate was 13% among patients with ESRD, as compared with 19%–26% among patients with other serious illnesses.

Figure 1.

Age-, sex-, and race-adjusted prevalence of advance directives in the last year of life among nursing home residents with ESRD, advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer, and advanced dementia. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Advance Directives in Patients with ESRD

Compared with patients with ESRD who had a treatment-limiting directive and a surrogate, those with only one or neither component were younger and more likely to be men and black (Table 2). They also had a higher prevalence of diabetes and chronic liver disease, and a lower prevalence of depression, dementia, and impaired decision-making skills.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients with ESRD in the month before death, stratified by presence of surrogate and treatment-limiting directive

| Characteristic | No Surrogate or Treatment-Limiting Directive (n=18,783) | Surrogate Alone (n=2581) | Treatment-Limiting Directive Alone (n=6438) | Surrogate and Treatment-Limiting Directive (n=2914) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr | 70±12 | 74±11 | 75±11 | 78±10 |

| Time receiving dialysis, yr | 3 (1, 6) | 3 (1, 5) | 3 (1, 5) | 3 (1, 5) |

| Time from nursing home admission, m | 7 (3, 10) | 8 (4, 11) | 8 (4, 11) | 8 (4, 11) |

| Hemodialysis (versus peritoneal dialysis), % | 98 | 98 | 98 | 97 |

| Women, % | 50 | 51 | 53 | 54 |

| Race, % | ||||

| White | 59 | 76 | 76 | 89 |

| Black | 37 | 21 | 20 | 9 |

| Other | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Hospital referral region spending, % | ||||

| Quintile 1 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 17 |

| Quintile 2 | 14 | 17 | 21 | 20 |

| Quintile 3 | 18 | 21 | 19 | 23 |

| Quintile 4 | 21 | 20 | 22 | 19 |

| Quintile 5 | 41 | 30 | 29 | 21 |

| Diabetes, % | 86 | 83 | 82 | 80 |

| Ischemic heart disease, % | 82 | 84 | 83 | 83 |

| Heart failure, % | 90 | 90 | 90 | 91 |

| Stroke, % | 45 | 43 | 45 | 44 |

| Chronic liver disease, % | 27 | 22 | 22 | 19 |

| Chronic lung disease, % | 65 | 66 | 67 | 67 |

| Cancer, % | 26 | 28 | 27 | 28 |

| Depression, % | 45 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Dementia, % | 32 | 35 | 36 | 39 |

| Impaired decision-making skills, % | 27 | 31 | 36 | 37 |

| Activities of Daily Living scorea | 16±10 | 17±7 | 17±7 | 17±7 |

| Days hospitalized in prior year | 43 (23, 74) | 37 (21, 65) | 34 (18, 58) | 29 (15, 50) |

Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD, or median (interquartile range), as appropriate.

The Activities of Daily Living score ranges from 0 to 28; higher scores indicate more functional limitations.

Treatments in the Last Month of Life and Site of Death for Patients with ESRD

In the last month of life, 69% of patients with ESRD were hospitalized, 43% were admitted to an ICU, 15% received mechanical ventilation, 5% received CPR, 2% received a gastrostomy tube, and 42% died in the hospital. Before death, 26% were admitted to hospice and 32% discontinued dialysis. Patients with a treatment-limiting directive were less likely to be hospitalized, receive intensive procedures, and die in the hospital, and more likely to receive hospice care and discontinue dialysis compared with patients without a treatment-limiting directive (Table 3). These associations persisted after adjustment for clinical characteristics and the presence of a surrogate. A similar pattern was observed between the presence of a surrogate and end-of-life treatments (Table 3), although the effect sizes were smaller. Results were similar in sensitivity analyses using propensity score–matching (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 3.

Association between treatment-limiting directive and surrogate decision-maker with treatments in the last month of life and site of death among patients with ESRD

| Treatment | Treatment-Limiting Directive | Adjusted Risk Difference, % (95% CI) | Surrogate Decision-Maker | Adjusted Risk Difference, % (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent % (n=21,364) | Present % (n=9352) | Absent % (n=25,221) | Present % (n=5495) | |||

| Hospitalization | 71 | 62 | −7 (−8 to −6) | 70 | 62 | −4 (−6 to −3) |

| Intensive care unit admission | 47 | 32 | −12 (−13 to −10) | 44 | 34 | −5 (−6 to −3) |

| Mechanical ventilation | 19 | 6 | −10 (−11 to −9) | 16 | 10 | −2 (−3 to −1) |

| CPR | 6 | 2 | −3 (−3 to −2) | 5 | 3 | −1 (−2 to 0) |

| Gastrostomy tube | 2 | 1 | −1 (−1 to 0) | 2 | 2 | 0 (0, 1) |

| Inpatient death | 46 | 34 | −9 (−10 to −8) | 44 | 35 | −4 (−6 to −3) |

| Hospice admission | 23 | 33 | 5 (4 to 6) | 25 | 31 | 1 (−1 to 2) |

| Dialysis discontinuation | 27 | 41 | 6 (5 to 7) | 30 | 41 | 2 (1 to 3) |

Models adjusted for age, sex, race, duration of dialysis, length of nursing home stay, days in hospital in prior year, dialysis modality, functional status, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, stroke, chronic liver disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, depression, dementia, impaired decision-making skills, hospital referral region spending quintile, treatment-limiting directive, and surrogate decision-maker, in addition to correlation of subjects within nursing home facilities. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

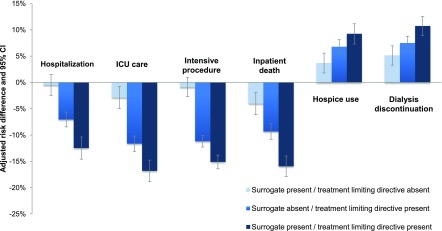

Compared with patients lacking a treatment-limiting directive and surrogate, the adjusted frequency of hospitalization was 13% lower, ICU admission was 17% lower, intensive procedures 13% lower, and inpatient death 14% lower, and the frequency of hospice use and dialysis discontinuation were higher by 5% and 7%, respectively, for patients with both measures in place (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Adjusted risk difference in the frequency of treatments in the last month of life and site of death for patients with ESRD who have a treatment-limiting directive and/or surrogate decision-maker compared with patients with neither measure. Estimates are adjusted for age, sex, race, duration of dialysis, length of nursing home stay, days in hospital in prior year, dialysis modality, functional status, diabetes, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, stroke, chronic liver disease, chronic lung disease, cancer, depression, dementia, impaired decision-making skills, and hospital referral region spending quintile in addition to correlation of subjects within nursing home facilities. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). ICU, intensive care unit.

Discordant End-of-Life Treatment among Patients with Treatment-Limiting Directive

There were 707 patients (8%) who received treatment that was discordant with their treatment-limiting directive (Table 4). “Do not resuscitate” orders were the most commonly requested treatment limitation and were followed in 94% of cases. “Do not hospitalize” orders were the least commonly requested treatment limitation and the least likely to be followed. Discordant treatment was more likely to occur among patients with a surrogate (relative risk, 1.45; 95% confidence interval, 1.20 to 1.75).

Table 4.

Frequency of discordant treatment among patients with ESRD who have a treatment-limiting directive

| Type of Treatment Limitation | Number of Patientsa | Receiving Discordant Treatment, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Do not resuscitate | 8590 | 549 (6) |

| Do not hospitalize | 286 | 153 (54) |

| Feeding restriction | 1457 | 22 (2) |

| Total patients with treatment-limiting directive | 9352 | 707 (8) |

Patients may have more than one requested treatment limitation.

Discussion

Among nursing home residents in the last year of life, patients receiving dialysis were far less likely to have a treatment-limiting directive or surrogate decision-maker compared with other nursing home residents with serious illnesses. Compared with patients with ESRD who did not have a treatment-limiting directive or a surrogate decision-maker, those with one or both of these advance directive components had fewer hospitalizations, ICU admissions, intensive procedures, and inpatient deaths, and were more likely to use hospice and discontinue dialysis before death. Furthermore, the vast majority of patients with a treatment-limiting directive received care that was concordant with their documented preferences. These findings are consistent with the possibility that limited engagement in advance care planning contributed to intensive patterns of end-of-life care in this population.

If the low prevalence of advance directives in patients with ESRD reflects infrequent engagement in advance care planning, what are the key barriers and how might they be addressed? Misplaced financial incentives favoring the volume rather than value of ESRD care has fueled care fragmentation and over-reliance on high-cost acute care. Fragmentation of care contributes to a lack of clarity around which provider should be responsible for initiating advance care planning (16,17). In addition, access to hospice services is contingent on dialysis discontinuation for most patients, a policy which may have the unintended consequence of delaying advance care planning for those patients whose goals and preferences are primarily palliative, but wish to continue dialysis. Finally, failure to recognize when patients are nearing the end of life, along with poor communication of prognosis, lead to missed opportunities to identify patient preferences and address goals of care.

Several health systems and policy approaches have been suggested to address these barriers, primarily targeting dialysis providers. These include systematic screening of patients receiving dialysis to identify those with a poor prognosis who may benefit from palliative care and advance care planning, and culturally-sensitive advance care planning interventions (18–20). Our findings suggest that functional impairment did not prompt advance care planning in the way that cognitive impairment did. Because nursing home admissions are often prompted by functional decline and involve transitions in care, these events may serve as useful triggers for advance care planning.

One suggested payment reform is the inclusion of documentation of advance care planning and surrogate decision-makers as quality metrics in the pay-for-performance ESRD Quality Incentive Program (21). Another payment reform that might indirectly incentivize advance care planning is bundling payments for comprehensive disease management rather than the current model in which payments are bundled for dialysis care only. The ESRD Disease Management Demonstration, conducted by Medicare, found that rates of advance directive completion could be increased as part of this payment model, although the effect this had on care near the end of life is not known (22).

The effectiveness of advance directives has been extensively debated. Whereas some studies have suggested that advance directives may be ineffective in aligning care with patient preferences or reducing use of intensive interventions (23,24), most recent studies suggest otherwise (25–28). Among patients receiving dialysis, small clinical trials suggest that advance care planning increases the likelihood of receiving care that is aligned with patient preferences, improves family bereavement outcomes, and increases use of hospice before death (3,20,29,30). These results are consistent with our finding that 92% of patients with a treatment-limiting directive received care that was concordant with their advance directive.

An interesting finding of our study is that the potential effect of treatment-limiting directives was not limited to lower use of resuscitation, but extended to lower use of other types of intensive interventions and more frequent use of hospice and dialysis discontinuation. We could not determine whether this reflected preferences not articulated in the advance directive, aspects of the advance directive that were not captured by the MDS instrument, or leeway in interpretation of advance directives by surrogates. One possibility is that the “effect” attributed to advance directives may be a marker for more general engagement in the advance care planning process. Whereas the focus of advance directives is on documenting preferences for life-sustaining treatments, advance care planning is intended to prepare patients and surrogates for a broader range of medical decisions (31). In support of this interpretation, a small clinical trial recently demonstrated that patients with ESRD who engaged in an advance care planning intervention with their surrogate were twice as likely to discontinue dialysis compared with patients who did not receive the intervention (3).

In our study, the separate contributions of surrogates and treatment-limiting directives seemed to be mutually reinforcing in most situations (32). At the same time, the presence of a surrogate was associated with a higher likelihood of receiving care that was discordant with a treatment-limiting directive. This seemingly contradictory finding may reflect the intended role of surrogate decision-makers; that is, to override an advance directive when unforeseen circumstances arise or goals change (10).

The strengths of our study include the large size and national scope of the study population, availability of detailed information on both the presence and content of advance directives, and linkage of prospective data on advance directives to downstream information on end-of-life utilization. This study also has several limitations. Our study sample was limited to patients residing in a nursing home. Because of the high level of debility among patients with ESRD near the end of life, the cohort for this study accounted for one third of all Medicare decedents receiving dialysis. Nevertheless, the results may not be generalizable to patients with ESRD living in the community. We lacked information about psychosocial factors, such as social support, which might influence the use of advance directives. We could not determine whether patients who lacked a treatment-limiting directive received care concordant with their preferences. We also lacked information regarding the patient’s experience near the end of life. Advance care planning practices may have changed since these data were collected. Finally, because this was an observational study, we could not determine whether advance directives were explicitly used in making medical decisions.

Among nursing home residents receiving dialysis, treatment-limiting directives and surrogate decision-makers are independently associated with lower use of intensive interventions, more frequent discontinuation of dialysis, and greater use of hospice care, but are seldom in place near the end of life. Efforts to increase engagement in advance care planning and expand the use of advance directives among patients receiving dialysis may offer untapped opportunities to better align end-of-life care with patient preferences and values.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by grant U01DK102150 from the National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

The data reported here have been supplied by the United States Renal Data System. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and should in no way be seen as an official policy or interpretation of the United States government or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Is the End in Sight for the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” Approach to Advance Care Planning?,” on pages 380–381.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.07510716/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Saran R, Li Y, Robinson B, Ayanian J, Balkrishnan R, Bragg-Gresham J, Chen JT, Cope E, Gipson D, He K, Herman W, Heung M, Hirth RA, Jacobsen SS, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, Leichtman AB, Lu Y, Molnar MZ, Morgenstern H, Nallamothu B, O’Hare AM, Pisoni R, Plattner B, Port FK, Rao P, Rhee CM, Schaubel DE, Selewski DT, Shahinian V, Sim JJ, Song P, Streja E, Kurella Tamura M, Tentori F, Eggers PW, Agodoa LY, Abbott KC: US Renal Data System 2014 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 66[Suppl 1]: S1–S305, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wachterman MW, Marcantonio ER, Davis RB, Cohen RA, Waikar SS, Phillips RS, McCarthy EP: Relationship between the prognostic expectations of seriously ill patients undergoing hemodialysis and their nephrologists. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1206–1214, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirchhoff KT, Hammes BJ, Kehl KA, Briggs LA, Brown RL: Effect of a disease-specific advance care planning intervention on end-of-life care. J Am Geriatr Soc 60: 946–950, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison SN: End-of-life care preferences and needs: Perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 195–204, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong SP, Kreuter W, O’Hare AM: Treatment intensity at the end of life in older adults receiving long-term dialysis. Arch Intern Med 172: 661–663, discussion 663–664, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsit SR, Keating NL: Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med 176: 1095–1102, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moss AH: Revised dialysis clinical practice guideline promotes more informed decision-making. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2380–2383, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holley JL, Stackiewicz L, Dacko C, Rault R: Factors influencing dialysis patients’ completion of advance directives. Am J Kidney Dis 30: 356–360, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurella Tamura M, Goldstein MK, Pérez-Stable EJ: Preferences for dialysis withdrawal and engagement in advance care planning within a diverse sample of dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 237–242, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sehgal A, Galbraith A, Chesney M, Schoenfeld P, Charles G, Lo B: How strictly do dialysis patients want their advance directives followed? JAMA 267: 59–63, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones AL, Moss AJ, Harris-Kojetin LD: Use of advance directives in long-term care populations. NCHS Data Brief, no 54. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE: Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med 361: 1539–1547, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawes C, Morris JN, Phillips CD, Mor V, Fries BE, Nonemaker S: Reliability estimates for the Minimum Data Set for nursing home resident assessment and care screening (MDS). Gerontologist 35: 172–178, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care: End-of-life chronic illness care. Available at: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/tools. Accessed December 4, 2015

- 15.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E: Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol 162: 199–200, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fung E, Slesnick N, Kurella Tamura M, Schiller B: A survey of views and practice patterns of dialysis medical directors toward end-of-life decision making for patients with end-stage renal disease. Palliat Med 30: 653–660, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Hare AM, Szarka J, McFarland LV, Taylor JS, Sudore RL, Trivedi R, Reinke LF, Vig EK: Provider perspectives on advance care planning for patients with kidney disease: Whose job is it anyway? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 855–866, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tamura MK, Meier DE: Five policies to promote palliative care for patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 1783–1790, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amro OW, Ramasamy M, Strom JA, Weiner DE, Jaber BL: Nephrologist-facilitated advance care planning for hemodialysis patients: A quality improvement project. Am J Kidney Dis 68: 103–109, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Song MK, Ward SE, Fine JP, Hanson LC, Lin FC, Hladik GA, Hamilton JB, Bridgman JC: Advance care planning and end-of-life decision making in dialysis: A randomized controlled trial targeting patients and their surrogates. Am J Kidney Dis 66: 813–822, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moss AH, Davison SN: How the ESRD quality incentive program could potentially improve quality of life for patients on dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 888–893, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arbor Research Collaborative for Health : End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD) Disease Management Demonstration Evaluation Report: Findings from 2006-2008, the First Three Years of a Five-Year Demonstration, December 2010. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Reports/downloads/Arbor_ESRD_EvalReport_2010.pdf. Accessed November 9, 2015

- 23.Teno J, Lynn J, Wenger N, Phillips RS, Murphy DP, Connors AF Jr, Desbiens N, Fulkerson W, Bellamy P, Knaus WA: Advance directives for seriously ill hospitalized patients: Effectiveness with the patient self-determination act and the SUPPORT intervention. SUPPORT Investigators. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 45: 500–507, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedraza SL, Culp S, Falkenstine EC, Moss AH: POST forms more than advance directives associated with out-of-hospital death: Insights from a state registry. J Pain Symptom Manage 51: 240–246, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Degenholtz HB, Rhee Y, Arnold RM: Brief communication: The relationship between having a living will and dying in place. Ann Intern Med 141: 113–117, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nicholas LH, Langa KM, Iwashyna TJ, Weir DR: Regional variation in the association between advance directives and end-of-life medicare expenditures. JAMA 306: 1447–1453, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM: Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med 362: 1211–1218, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hickman SE, Nelson CA, Moss AH, Tolle SW, Perrin NA, Hammes BJ: The consistency between treatments provided to nursing facility residents and orders on the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form. J Am Geriatr Soc 59: 2091–2099, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W: The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ 340: c1345, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt RJ, Weaner BB, Long D: The power of advance care planning in promoting hospice and out-of-hospital death in a dialysis unit. J Palliat Med 18: 62–66, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sudore RL, Fried TR: Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: Preparing for end-of-life decision making. Ann Intern Med 153: 256–261, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Escher M, Perneger TV, Rudaz S, Dayer P, Perrier A: Impact of advance directives and a health care proxy on doctors’ decisions: A randomized trial. J Pain Symptom Manage 47: 1–11, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.