Abstract

Introduction

Patients with COPD who remain symptomatic on long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy may benefit from step-up therapy to a long-acting bronchodilator combination. This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of umeclidinium (UMEC)/vilanterol (VI) in patients with moderate COPD who remained symptomatic on tiotropium (TIO).

Methods

In this randomized, blinded, double-dummy, parallel-group study (NCT01899742), patients (N=494) who were prescribed TIO for ≥3 months at screening (forced expiratory volume in 1 s [FEV1]: 50%–70% of predicted; modified Medical Research Council [mMRC] score ≥1) and completed a 4-week run-in with TIO were randomized to UMEC/VI 62.5/25 µg or TIO 18 µg for 12 weeks. Efficacy assessments included trough FEV1 at Day 85 (primary end point), 0–3 h serial FEV1, rescue medication use, Transition Dyspnea Index (TDI), St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), and COPD Assessment Test (CAT). Safety evaluations included adverse events (AEs).

Results

Compared with TIO, UMEC/VI produced greater improvements in trough FEV1 (least squares [LS] mean difference: 88 mL at Day 85 [95% confidence interval {CI}: 45–131]; P<0.001) and FEV1 after 5 min on Day 1 (50 mL [95% CI: 27–72]; P<0.001). Reductions in rescue medication use over 12 weeks were greater with UMEC/VI versus TIO (LS mean change: −0.1 puffs/d [95% CI: −0.2–0.0]; P≤0.05). More patients achieved clinically meaningful improvements in TDI score (≥1 unit) with UMEC/VI (63%) versus TIO (49%; odds ratio at Day 84=1.78 [95% CI: 1.21–2.64]; P≤0.01). Improvements in SGRQ and CAT scores were similar between treatments. The incidence of AEs was similar with UMEC/VI (30%) and TIO (31%).

Conclusion

UMEC/VI step-up therapy provides clinical benefit over TIO monotherapy in patients with moderate COPD who are symptomatic on TIO alone.

Keywords: COPD, LABA, LAMA, step-up, tiotropium, umeclidinium/vilanterol

Introduction

Despite the availability of effective bronchodilator therapies, ~90% of patients with COPD remain symptomatic on long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) mono-therapy or long-acting β2-agonist (LABA) monotherapy, and step-up therapy to a long-acting bronchodilator combination may be beneficial.1 Indeed, the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines recommend the alternative use of LAMA and LABA combinations in patients who remain symptomatic on long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy.2

The dual long-acting bronchodilator combination of the LAMA umeclidinium (UMEC) and the LABA vilanterol (VI) is an approved maintenance treatment for COPD in the US, Canada, the EU, and several other countries.3–5 Previous clinical trials have shown that UMEC/VI provides greater improvements in lung function than UMEC, VI, or the LAMA tiotropium (TIO) monotherapy, with similar or greater improvements in dyspnea, rescue medication use, and health-related quality of life in patients with COPD.6–8 However, these studies recruited patients with moderate-to-very severe lung function impairment and high symptomatic burden (GOLD B/D) and have not specifically evaluated UMEC/VI in patients with moderate lung function impairment, who remained symptomatic despite regular use of long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy.

This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of UMEC/VI treatment compared with TIO in a less severe patient (GOLD A/B) population than previous evaluations of UMEC/VI.

Methods

Study design

This was a multicenter, randomized, blinded, double-dummy, parallel-group study (NCT01899742; GSK identifier: DB2116960) performed from September 2014 to July 2015 at 64 study centers across nine countries (Argentina, Estonia, Germany, Norway, Russian Federation, South Africa, Sweden, Ukraine, and the US). Patients who completed a 4-week run-in period on open-label TIO (18 µg once-daily via HandiHaler®) were randomized to receive blinded UMEC/VI or TIO for 12 weeks.

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients who participated in the study. The study was approved by Ethik-Kommission der Landesaerztekammer Hessen (Frankfurt-am-Main), as well as each relevant national, regional, or independent ethics committee or institutional review boards and was performed in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP) guidelines and all applicable patient privacy requirements and the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, 2013.9,10

Patients

Patients eligible for inclusion in the run-in period were ≥40 years of age with a diagnosis of COPD according to the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society definition,11 had a post-salbutamol forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) of ≤70% and ≥50% of normal predicted values (moderate airflow limitation), had a modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) Dyspnea Scale score of ≥1 at screening, and were prescribed TIO for at least 3 months prior to screening. Exclusion criteria at screening included the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) or maintenance COPD medications other than TIO in the 3 months prior to screening (including other LAMAs, LABAs, LAMA/LABA combinations, ICS/LABA combinations, phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors, theophyllines, and oral β2-agonists), a current diagnosis of asthma, respiratory diseases other than COPD considered clinically significant by the study investigator, and more than one moderate-to-severe COPD exacerbation in the past 12 months (defined as worsening symptoms of COPD requiring treatment with oral/systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, or in-patient hospitalization).

Patients were eligible for randomization after the 4-week run-in period if they had an mMRC score ≥1 at randomization (mMRC scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater impairment; an mMRC score of 1 refers to patients reporting that “I get short of breath when hurrying on the level or walking up a slight hill”), did not experience moderate-to-severe exacerbations or lower respiratory tract infections requiring antibiotic treatment between screening and randomization, and had treatment compliance with TIO of ≥80% and ≤120% during the run-in period.

Treatments

Patients were randomized in a 1:1 ratio using a random code generator (RandAll) and assigned to treatment group via an interactive voice/web recognition system. All patients and physicians were masked to assigned treatment during the studies. Patients received either once-daily UMEC/VI 62.5/25 µg via ELLIPTA® dry powder inhaler (DPI; delivering 55/22 µg4,5) and once-daily placebo via HandiHaler® or once-daily TIO 18 µg (delivering 10 µg12,13) via the HandiHaler® and once-daily placebo via ELLIPTA® DPI for 12 weeks.

As UMEC/VI and TIO are delivered via different inhaler devices; a double-dummy design was used for dosing, where patients received two inhalers, one containing active drug and the other placebo. However, the TIO capsules had trade markings not present on the placebo capsules, although they were closely matched in color. As the study had a parallel-group design, the capsule type was consistent for each patient for the duration of the study. Both the TIO and placebo blister packages were covered with opaque overlabels to hide the information on the TIO packaging. The HandiHaler® DPIs, which were used with both TIO and placebo blisters, were covered with labels to mask identifying marks on the inhaler. Staff involved with safety and efficacy assessments were not present during dosing in the clinic to maintain blinding.

Outcomes and assessments

The primary end point was trough FEV1 on Day 85. The secondary end point was FEV1 at 3 h postdose on Day 84. Other lung function end points included trough FEV1 on Days 2, 28, 56, and 84; serial FEV1 on Days 1, 28, and 56; weighted mean FEV1 over 3 h on Days 1, 28, 56, and 84; and trough forced vital capacity (FVC) on Days 2, 28, 56, 84, and 85. In a subset of patients, termed the 24-h population, serial FEV1 over 24 h postdose on Days 1 and 84 was performed. Other efficacy end points included the percentage of rescue-free days and the number of puffs of rescue medication during the study. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) included Transition Dyspnea Index (TDI) focal score and the proportion of responders (defined as patients with a TDI focal score of ≥1 unit14) on Days 28, 56, and 84; St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) total score and the proportion of responders (defined as patients with a reduction from baseline in SGRQ score of ≥4 units15) on Days 28 and 84; and COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score and the proportion of responders on Days 28 and 84 (patients with a ≥2-unit reduction from baseline16). Safety assessments included monitoring the incidence of adverse events (AEs), AEs considered to be drug-related by the investigator, vital signs, and the incidence of moderate-to-severe COPD exacerbations.

Statistical analysis

Sample size calculations used a two-sided 5% significance level and an estimate of residual standard deviation (SD) for trough FEV1 of 220 mL. For the primary analysis, it was estimated that 208 evaluable patients per treatment group would have 90% power to detect a 70 mL difference in FEV1 between treatments. The primary end point was analyzed using a mixed model repeated measures analysis, including trough FEV1 at Days 2, 28, 56, 84, and 85. Covariates included baseline FEV1 (mean values at 23 h and 24 h after the last TIO dose prior to randomization), inclusion in the 24-h population (yes/no), day, treatment, center group, day by baseline interaction, where day was nominal, and day by treatment interaction. The proportion of patients achieving an increase of ≥100 mL above baseline in trough FEV1 was analyzed using a logistic regression model with treatment as an explanatory variable. Baseline FEV1, inclusion in the 24-h population (yes/no), and center group were included as covariates in the model.

The intent-to-treat (ITT) population (all randomized patients receiving at least one dose of study medication) was the primary analysis for all study end points. The 24-h population comprised all patients for whom 24-h data were collected. The sample size (~200 patients) of the 24-h population was chosen to provide a sufficient number of patients for a descriptive evaluation of bronchodilator response over 24 h. For reporting, patients were grouped into different GOLD categories based on their mMRC score, lung function impairment, and exacerbation history.2

Results

Patients

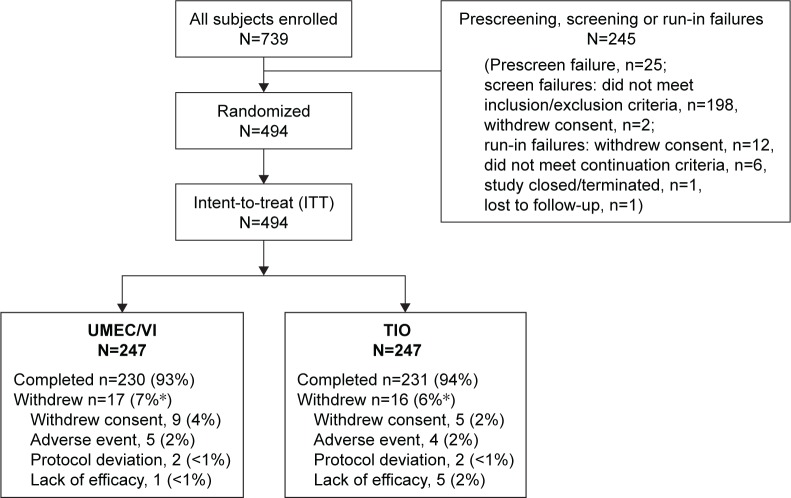

Of the 739 patients enrolled, 494 met all eligibility criteria at screening, remained symptomatic on TIO monotherapy at the end of the run-in period, and were eligible to be included in the ITT population (n=247 in each group; Figure 1). The majority of patients in the UMEC/VI (93%) and TIO (94%) groups completed the study. Overall, the most common reasons for study withdrawal in the UMEC/VI and TIO groups were withdrawal of consent accounting for nine (4%) and five (2%) of withdrawals, and AEs accounting for five (2%) and four (2%) patient withdrawals, respectively. AEs leading to withdrawal in the UMEC/VI group were individual events (<1%) of cerebrovascular accident, sciatica, pneumothorax, pneumonia, and gastrointestinal pain and in the TIO group were individual events of COPD exacerbation (reported for two patients), cervical vertebral fracture, and events of influenza and aphonia (both events reported in a single patient). Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were similar across treatment groups (Table 1). At screening, patients in the ITT population had moderate airflow obstruction (GOLD stage II) and were primarily GOLD group A (25%) or B (62%; Table 1). At randomization, the mean mMRC dyspnea score was 1.8 in both groups, with 73% of patients having an mMRC score ≥2. Mean rescue albuterol use was 1.1 to 1.2 puffs/d during the run-in period. Overall mean patient treatment compliance during the 12-week treatment period was high among patients in both groups (UMEC/VI: 99%, TIO: 98%) for both delivery devices (ELLIPTA®: UMEC/VI 99%, TIO: 98% and HandiHaler®: UMEC/VI: 99%, TIO: 98%).

Figure 1.

Summary of patient disposition.

Notes: *Percentages may not add up due to rounding.

Abbreviations: TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics (ITT population)

| Characteristics | UMEC/VI (N=247) |

TIO (N=247) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 64.5 (8.7) | 64.3 (8.7) |

| Male, n (%) | 163 (66) | 160 (65) |

| Ethnicity, Caucasian, n (%) | 244 (99) | 242 (98) |

| Current smoker at screening, n (%)a | 129 (52) | 118 (48) |

| Smoking pack-years at screening, mean (SD)b | 38.6 (20.5) | 40.4 (20.2) |

| Lung function | ||

| Post-salbutamol FEV1 at screening, L, mean (SD) | 1.79 (0.42) | 1.75 (0.38) |

| Post-salbutamol FEV1/FVC at screening, mean (SD) | 53.1 (8.2) | 52.9 (8.4) |

| Post-salbutamol % predicted FEV1, mean (SD) | 59.8 (5.5) | 59.4 (5.3) |

| Reversible to salbutamol at screening, n (%)c,d | 60 (24) | 62 (25) |

| % reversibility to salbutamol at screening, mean (SD)c,d | 8.2 (12.2) | 7.7 (10.0) |

| GOLD grade II at screening, n (%) | 247 (100) | 247 (100) |

| Baseline symptomatology/risk, mean (SD) | ||

| mMRC dyspnea score at screening | 1.9 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.6) |

| mMRC dyspnea score at randomization | 1.8 (0.6) | 1.8 (0.6) |

| BDI focal score at Day 1e | 6.5 (1.3) | 6.5 (1.4) |

| SGRQ score at baselinef | 41.3 (14.4) | 42.3 (14.8) |

| CAT score at baseline | 16.7 (6.2) | 16.4 (6.5) |

| % rescue-free days at baselineg | 48.8 (40.4) | 51.9 (40.6) |

| Rescue medication use, puffs/d at baselineg | 1.1 (1.4) | 1.2 (1.8) |

| Number of moderate-to-severe COPD exacerbationsh 12 months prior to screening, n (%) | 86 (35) | 81 (33) |

| GOLD category at screening, n (%)i | ||

| A | 58 (23) | 67 (27) |

| B | 161 (65) | 146 (59) |

| C | 1 (<1) | 3 (1) |

| D | 27 (11) | 31 (13) |

Notes:

Reclassified: patient reclassified as current smoker if they had smoked within 6 months of screening.

Smoking pack-years = (number of cigarettes smoked per day/20) × number of years smoked.

Reversibility was defined as an increase in FEV1 of ≥12% and ≥200 mL following administration of albuterol.

TIO, n=246.

UMEC/VI, n=240; TIO, n=245.

UMEC/VI, n=242; TIO, n=245.

UMEC/VI, n=246.

Defined as worsening symptoms of COPD requiring treatment with oral/systemic corticosteroids, antibiotics, or in-patient hospitalization.

According to mMRC score, lung function impairment, and exacerbation history.

Abbreviations: BDI, baseline dyspnea index; CAT, COPD Assessment Test; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; GOLD, Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease; ITT, intent-to-treat; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council; SD, standard deviation; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umecli dinium; VI, vilanterol.

Efficacy

Lung function

Primary end point

For the primary end point of trough FEV1 at Day 85, UMEC/VI treatment resulted in an 88 mL improvement over TIO (95% confidence interval [CI]: 45–131; P<0.001; Table 2).

Table 2.

Lung function outcomes (ITT population)

| Outcome measure | UMEC/VI (N=247) |

TIO (N=247) |

|---|---|---|

| Change from baseline in trough FEV1, mL | ||

| Day 2 | ||

| na | 238 | 238 |

| LS mean (SE) | 91 (12.7) | −9 (12.7) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 101 (65–136)*** | |

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 237 | 230 |

| LS mean (SE) | 64 (14.6) | 0 (14.7) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 64 (23–105)** | |

| Day 56 | ||

| na | 232 | 226 |

| LS mean (SE) | 63 (14.0) | −9 (14.2) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 72 (33–112)*** | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 226 | 229 |

| LS mean (SE) | 65 (15.5) | −25 (15.4) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 90 (47–113)*** | |

| Day 85 | ||

| na | 224 | 225 |

| LS mean change (SE) | 74 (15.5) | −14 (15.5) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 88 (45–131)*** | |

| Change from baseline in FEV1 at 3 h postdose, mL | ||

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 225 | 228 |

| LS mean (SE) | 164 (17.8) | 91 (17.7) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 73 (24–122)** | |

| Change from baseline in weighted mean FEV1 at 0–3 h postdose, mL | ||

| Day 1 | ||

| na | 239 | 240 |

| LS mean (SE) | 141 (9.5) | 87 (9.5) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 55 (28–81)*** | |

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 221 | 218 |

| LS mean (SE) | 161 (15.2) | 81 (15.3) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 80 (37–122)*** | |

| Day 56 | ||

| na | 219 | 218 |

| LS mean (SE) | 148 (15.6) | 92 (15.7) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 56 (12–100)* | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 225 | 228 |

| LS mean (SE) | 151 (16.4) | 79 (16.4) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 72 (26–118)** | |

Notes:

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

P<0.001.

Number of subjects with analyzable data at the current time point.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least squares; SE, standard error; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

Secondary end point

For the secondary end point of FEV1 at 3 h postdose on Day 84, UMEC/VI treatment produced a 73 mL improvement over TIO (95% CI: 24–122; P<0.01; Table 2).

Other lung function end points

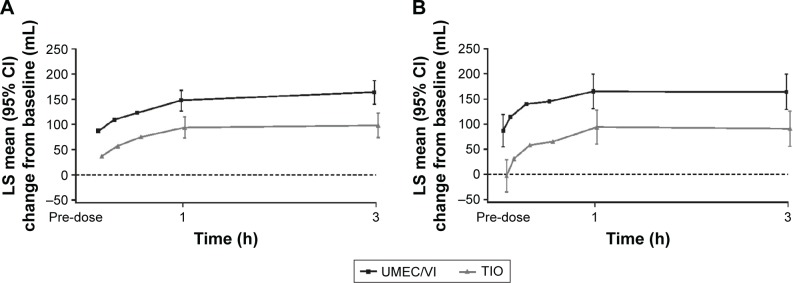

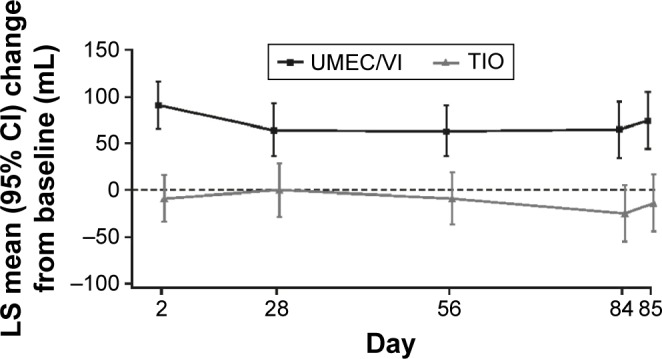

Greater improvements in trough FEV1 with UMEC/VI over TIO were also observed at all other assessments from Day 2 onward (P<0.01; Figure 2). Additionally, a greater proportion of patients achieved a ≥100 mL improvement in trough FEV1 at Day 85 with UMEC/VI (44%) compared with TIO (30%), with UMEC/VI versus TIO resulting in a higher odds of achieving a ≥100 mL improvement in trough FEV1 (odds ratio: 1.89 [95% CI: 1.27–2.81]; P<0.01) at Day 85. Mean serial FEV1 values demonstrated improvements favoring UMEC/VI over TIO as early as 5 min postdose on Day 1 (Figure 3A; difference of 50 mL [95% CI: 27–72]; P<0.001), which was maintained for all serial FEV1 time points up to 3 h (P<0.05; Day 28: Figure S1A, Day 56: Figure S1B, and Day 84: Figure 3B). Additionally, UMEC/VI treatment resulted in statistically significant improvements over TIO in weighted mean FEV1 0–3 h postdose (Table 2) and trough FVC (Table S1).

Figure 2.

LS mean (SE) change from baseline in trough FEV1 (ITT population).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least squares; SE, standard error; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

Figure 3.

Serial LS mean change (95% CI) from baseline in FEV1 over 0–3 h on Day 1 (A) and Day 84 (B; ITT population).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least squares; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

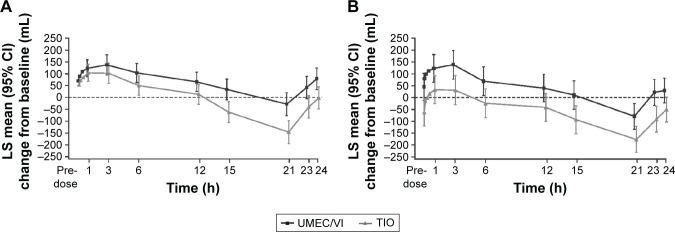

In the subset of patients with serial spirometry data over 24 h (UMEC/VI, n=94 and TIO, n=92), improvements in serial FEV1 values were obtained at all time points measured with UMEC/VI compared with TIO (Day 1: Figure 4A and Day 84: Figure 4B). UMEC/VI resulted in greater improvements in 0–24 h weighted mean FEV1 over TIO at Days 1 and 84 (treatment differences of 69 mL [95% CI: 20–118] and 102 mL [95% CI: 28–176], respectively, P<0.01).

Figure 4.

Serial LS mean change (95% CI) from baseline in FEV1 over 0–24 h on Day 1 (A) and Day 84 (B; 24-h population).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; LS, least squares; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

Patient-reported outcomes

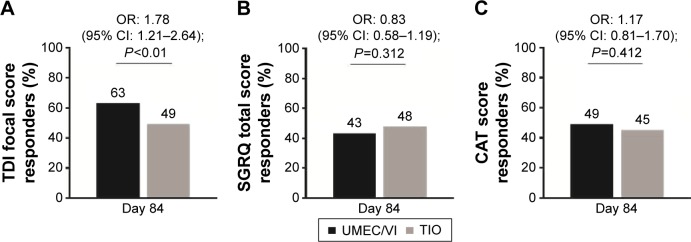

UMEC/VI resulted in a greater improvement in the number of rescue-free days over 12 weeks compared with TIO (median estimated difference 2.3 days [95% CI: 0.0–4.8; P<0.01]). There was also a greater reduction in rescue medication use over 12 weeks, favoring UMEC/VI over TIO (least squares mean change difference: −0.1 puffs/d [95% CI: −0.2–0.0]; P<0.05). TDI focal scores were improved with UMEC/VI compared with TIO at Day 28 but not at Days 56 and 84 (Table 3). The odds of being a responder versus a nonresponder according to TDI score were significantly higher for patients receiving UMEC/VI compared with TIO at Day 84 (Figure 5A; Table S2). Improvements in SGRQ and CAT scores on Days 28 and 84 were similar between treatment groups (Table 3). The proportion of SGRQ and CAT responders was similar between groups (Figure 5B and C; Table S2).

Table 3.

Patient-reported outcomes (ITT population)

| Outcome measure | UMEC/VI (N=247) |

TIO (N=247) |

|---|---|---|

| TDI score | ||

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 235 | 238 |

| LS mean (SE) | 1.8 (0.16) | 1.3 (0.16) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 0.5 (0.0–0.9)* | |

| Day 56 | ||

| na | 232 | 235 |

| LS mean (SE) | 1.9 (0.15) | 1.8 (0.15) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 0.1 (−0.3–0.5) | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 226 | 233 |

| LS mean (SE) | 2.3 (0.16) | 1.9 (0.16) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 0.4 (−0.1–0.8) | |

| SGRQ total score | ||

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 232 | 237 |

| LS mean change (SE) | −3.23 (0.59) | −2.67 (0.59) |

| Difference (95% CI) | −0.55 (−2.20–1.09) | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 225 | 232 |

| LS mean change (SE) | −4.41 (0.68) | −4.21 (0.67) |

| Difference (95% CI) | −0.20 (−2.09–1.68) | |

| CAT score | ||

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 242 | 240 |

| LS mean change (SE) | −1.56 (0.31) | −1.17 (0.31) |

| Difference (95% CI) | −0.39 (−1.25–0.48) | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 233 | 235 |

| LS mean change (SE) | −2.10 (0.36) | −1.84 (0.35) |

| Difference (95% CI) | −0.26 (−1.25–0.72) |

Notes:

P<0.05.

Number of subjects with analyzable data at the current time point.

Abbreviations: CAT, COPD Assessment Test; CI, confidence interval; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least squares; SE, standard error; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; TDI, Transition Dyspnea Index; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

Figure 5.

Responder analysis of clinically relevant change from baseline in breathlessness assessed by (A) TDI focal score, and health status assessed by either (B) SGRQ total score or (C) CAT score (ITT population).

Notes: TDI responder defined as a ≥1-unit improvement from baseline; SGRQ total score responder defined as a ≥4-unit reduction from baseline; and CAT score defined as a ≥2-unit reduction from baseline.

Abbreviations: CAT, COPD Assessment Test; CI, confidence interval; ITT, intent-to-treat; OR, odds ratio; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; TDI, Transition Dyspnea Index; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

Safety

The incidence of AEs was similar between the UMEC/VI (30%) and TIO (31%) groups, with the most common AEs (ie, an incidence of ≥3% patients in either treatment arm) being nasopharyngitis and headache (Table 4). In total, six (2%) patients experienced on-treatment, nonfatal, serious AEs (SAEs) in each of the UMEC/VI and TIO groups. SAEs reported with UMEC/VI were pneumothorax, atrial flutter, myocardial infarction, appendicitis, pneumonia, and worsening of benign prostatic hyperplasia; with TIO there were two separate events of worsening of COPD, and events of dehydration, hypotension, worsening of benign prostatic hyperplasia, cervical vertebral fracture, and pancreatic cancer. One death occurred on-treatment during the study due to a cerebrovascular accident in the UMEC/VI group and was identified as not treatment related by the reporting investigator.

Table 4.

Summary of AEs and COPD exacerbations (ITT population)

| n (%) | UMEC/VI (N=247) |

TIO (N=247) |

|---|---|---|

| On-treatment AEs | 75 (30) | 77 (31) |

| On-treatment drug-related AEs | 3 (1) | 8 (3) |

| Any AEs leading to withdrawal/discontinuation of medication | 5 (2) | 4 (2) |

| On-treatment nonfatal SAE | 6 (2) | 6 (2) |

| On-treatment fatal SAE | 1 (<1) | 0 |

| AEs reported in ≥3% patients in either treatment arm | ||

| Nasopharyngitis | 18 (7) | 17 (7) |

| Headache | 16 (6) | 18 (7) |

| Patients experiencing a COPD exacerbation | 2 (<1) | 8 (3) |

| Cardiovascular events of special interesta | 4 (1.6) | 3 (1.2) |

Notes: AEs with onset during the follow-up period were considered on-treatment and were assigned to the treatment previously received.

Standardized MedDRA terms included cardiac arrhythmias, cardiac failure, ischemic heart disease, central nervous system hemorrhages, and cerebrovascular conditions.

Abbreviations: AEs, adverse events; ITT, intent-to-treat; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; SAE, serious adverse event; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

The incidence of any cardiovascular AEs of special interest (ie, those related cardiac arrhythmias, cardiac failure, ischemic heart disease, and cerebrovascular conditions) was low and similar between the UMEC/VI (n=4 [1.6%]) and TIO (n=3 [1.2%]) groups. On-treatment COPD exacerbations were reported for two (<1%) and eight (3%) patients in the UMEC/VI and TIO groups, respectively.

Discussion

This randomized, parallel-group study of the once-daily combination of UMEC/VI delivered via the ELLIPTA® inhaler demonstrated statistically significant improvements in lung function, as measured by the primary and secondary end points of trough FEV1 and 3 h post-dose FEV1, respectively, over 12 weeks compared with TIO in patients with moderate COPD who remained symptomatic, despite the regular use of TIO. These findings were supported by the additional lung function end points of 0–3 h weighted mean FEV1, 24-h weighted mean FEV1, and trough FVC.

The current study evaluated patients with moderate COPD based on a postbronchodilator FEV1 of 50%–70% of predicted normal values and enrolled patients with an mMRC score ≥1, despite at least 3 months treatment with TIO before the study. Based on mMRC GOLD criteria,2 most patients were either GOLD group A (25%) or B (62%) at screening, although <1% and 12% of patients were identified as GOLD groups C and D, respectively. After a further month of TIO treatment during the run-in period, the vast majority (73%) of patients reported an mMRC score of ≥2. This indicated the potential for further optimization of treatment with dual bronchodilator step-up therapy in the enrolled population. Two previous studies comparing UMEC/VI with TIO in COPD,6,7 which evaluated patients with moderate-to-very severe airflow obstruction (ie, FEV1 <70% of normal predicted values), showed 60–112 mL improvements in trough FEV1 with UMEC/VI over TIO after 6 months of treatment.6,7 These findings are consistent with the 88 mL improvement in trough FEV1 for UMEC/VI over TIO observed in this study of patients with moderate airflow obstruction. However, this is the first study to demonstrate these improvements in patients with GOLD A classification of COPD.

Generally, improvements in the patient-reported measures were similar with UMEC/VI and TIO and met the 1.0 unit minimal clinically important difference (MCID).14–16 Although treatment differences for TDI score were numerically larger for UMEC/VI compared with TIO, mean differences were modest, ie, ≤0.5 difference in score at all time points and a statistically significant difference was only demonstrated on Day 28. This magnitude of response, although small, is consistent with the size of response seen previously when comparing dual bronchodilators versus their own mono bronchodilator components.17 Moreover, the TDI responder analysis indicated a greater odds of having a clinically meaningful improvement in dyspnea with UMEC/VI compared with TIO at Day 84. This incremental increase in response rate with dual bronchodilation over TIO is consistent with greater reductions in rescue medication use with UMEC/VI compared with TIO, despite very low baseline usage (1.1–1.2 puffs/d) relative to a previous trial of patients with moderate-to-very severe disease (baseline usage: 3.2–3.3 puffs/d).7 This suggests that despite the overall modest symptom burden, more patients demonstrated reductions in symptoms, in addition to improvements in lung function with UMEC/VI compared with TIO.14

Previous studies have not consistently demonstrated greater improvements in subjectively assessed PROs with long-acting bronchodilator combination therapy compared with monotherapy.6–8,18,19 In the current study, improvements in SGRQ and CAT scores from baseline that met MCID thresholds were seen in the UMEC/VI and TIO groups, despite the enrollment of patients who remained symptomatic as defined by mMRC score >1, while receiving TIO for 4 weeks during the run-in period and for at least 3 months prior to screening. This suggests subjective PROs are strongly influenced by clinical trial participation, that is, the Hawthorne effect, which may impair the ability to differentiate treatment-related effects on these outcomes.20 This phenomenon has also been consistently seen with all LAMA and LABA monotherapies compared with placebo, as demonstrated in a recent meta-analysis of 40 randomized controlled trials.21 As a result, new PROs may need to be developed to overcome the Hawthorne effect and distinguish between active treatments.

The safety and tolerability profiles of both treatments were similar. Consistent with previous studies of UMEC/VI versus UMEC, VI, and TIO alone, the most common AEs in the current study were headache and nasopharyngitis.6–8 No difference in the incidence of cardiovascular AEs was observed between UMEC/VI and TIO. A small numerical difference in exacerbations favoring UMEC/VI over TIO (two vs eight events, respectively) was seen despite 86%–89% of the study population having COPD of moderate severity and an infrequent history of exacerbations (GOLD A/B). Both reductions and no change in the number of COPD exacerbations have been demonstrated with UMEC/VI and LAMA or LABA monotherapies compared with placebo,8,22–24 but the current study was not designed to compare the treatment effects on COPD exacerbations. The safety findings of the current study are consistent with the favorable efficacy/safety profile reported for the LABA/LAMA combinations versus monotherapy in a network meta-analysis including >27,000 patients.25 Overall, the results of the current study suggest that step-up therapy from TIO to UMEC/VI improves lung function and increases the odds of experiencing a clinically meaningful improvement in dyspnea, without increasing the risk of AEs and provides an overall positive risk-benefit. As the duration of this study was relatively short (12 weeks) compared with previous trials, longer-term studies are required to confirm the durability of these results in a similar population. The GOLD guidelines on the management of COPD recommend LAMA/LABA combinations as an alternative treatment option to LAMA monotherapy across a range of disease severities (GOLD B, C, and D). This was the first study to demonstrate that patients with moderate COPD (predominantly GOLD A and B) who remained symptomatic on TIO monotherapy obtained incremental benefit from step-up therapy with a long-acting bronchodilator combination.

Supplementary materials

Serial LS mean change (95% CI) from baseline in FEV1 over 0–3 h on Day 28 (A) and Day 56 (B; ITT population).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least squares; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

Table S1.

Additional lung function outcomes (ITT population)

| Outcome measure | UMEC/VI (N=247) |

TIO (N=247) |

|---|---|---|

| Trough FVC (L) | ||

| Day 2 | ||

| na | 238 | 238 |

| LS mean (SE) | 131 (18.3) | 6 (18.3) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 125 (74–176)*** | |

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 237 | 230 |

| LS mean (SE) | 56 (20.5) | −4 (20.7) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 59 (2–116)* | |

| Day 56 | ||

| na | 232 | 226 |

| LS mean (SE) | 36 (20.6) | −23 (20.8) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 59 (2–117)* | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 226 | 229 |

| LS mean (SE) | 47 (22.7) | −50 (22.7) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 97 (34–160)** | |

| Day 85 | ||

| na | 224 | 225 |

| LS mean change (SE) | 63 (22.6) | −41 (22.6) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 104 (41–166)** |

Notes:

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

P<0.001.

Number of subjects with analyzable data at the current time point.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FVC, forced vital capacity; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least squares; SE, standard error; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

Table S2.

Patient reported outcome responder analyses (ITT population)

| Outcome measure | UMEC/VI (N=247) |

TIO (N=247) |

|---|---|---|

| TDI score responder analysis | ||

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 240 | 245 |

| Responder,b n (%) | 139 (58) | 112 (46) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.67 (1.14–2.45)** | |

| Day 56 | ||

| na | 240 | 245 |

| Responder,b n (%) | 136 (57) | 124 (51) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.25 (0.85–1.84) | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 240 | 245 |

| Responder,b n (%) | 151 (63) | 121 (49) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.78 (1.21–2.64)** | |

| SGRQ total score responder analysis | ||

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 237 | 244 |

| Responder,c n (%) | 99 (42) | 100 (41) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.05 (0.73–1.53) | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 242 | 245 |

| Responder,c n (%) | 104 (43) | 117 (48) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 0.83 (0.58–1.19) | |

| CAT score responder analysis | ||

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 247 | 247 |

| Responder,d n (%) | 118 (48) | 99 (40) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.40 (0.96–2.04) | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 247 | 247 |

| Responder,d n (%) | 121 (49) | 111 (45) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.17 (0.81–1.70) | |

Notes:

P<0.01.

Number of subjects with analyzable data at the current time point.

Defined as a ≥1-unit improvement from baseline.

Defined as a ≥4-unit improvement from baseline.

Defined as a ≥2-unit improvement from baseline.

Abbreviations: CAT, COPD Assessment Test; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least squares; SE, standard error; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; TDI, Transition Dyspnea Index; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Maria Rosario Gonzalez from GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) for her assistance in the operation and management of the study. Additionally, the authors would like to thank Alex Lowe, PhD, from Fishawack Indicia Ltd, who provided editorial assistance with developing this manuscript (in the form of writing assistance, including development of the initial draft, assembling tables and figures, collating authors comments, grammatical editing, and referencing), funded by GSK. This study was funded by GSK (NCT01899742; GSK identifier: 116960).

Footnotes

Author contributions

CJK, DVG, C-QZ, AC, and JHR contributed to the study concept and design and were involved in data analysis and interpretation. EMK participated in data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation. WAF contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. All authors contributed toward drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

EMK has served on advisory boards, speaker panels, and received travel reimbursement from Amphastar, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Forest, Ironwood, Mylan, Novartis, Pearl, Sunovion, Targacept, Teva, and Theravance; has conducted multicenter clinical research trials for ~40 pharmaceutical companies. CJK, DVG, C-QZ, AC, JHR, and WAF are employees of GSK and hold stocks/shares in GSK. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Dransfield MT, Bailey W, Crater G, Emmett A, O’Dell DM, Yawn B. Disease severity and symptoms among patients receiving monotherapy for COPD. Prim Care Respir J. 2011;20(1):46–53. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2010.00059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GOLD [homepage on the Internet] Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. 2016. [Accessed January 4, 2017]. [cited July 25, 2016]. Available from: http://www.goldcopd.com/

- 3.Blair HA, Deeks ED. Umeclidinium/vilanterol: a review of its use as maintenance therapy in adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Drugs. 2015;75(1):61–74. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0326-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.GSK ANORO™ ELLIPTA® [prescribing information] 2014. [Accessed September 2015]. Available from: https://www.gsksource.com/gskprm/htdocs/documents/ANORO-ELLIPTA-PI-MG.PDF.

- 5.GSK [webpage on the Internet] ANORO™ ELLIPTA® summary of product characteristics. 2014. [Accessed September 2015]. Available from: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/28949#INDICATIONS.

- 6.Decramer M, Anzueto A, Kerwin E, et al. Efficacy and safety of umeclidinium plus vilanterol versus tiotropium, vilanterol, or umeclidinium monotherapies over 24 weeks in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from two multicentre, blinded, randomised controlled trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(6):472–486. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maleki-Yazdi MR, Kaelin T, Richard N, Zvarich M, Church A. Efficacy and safety of umeclidinium/vilanterol 62.5/25 mcg and tiotropium 18 mcg in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results of a 24-week, randomized, controlled trial. Respir Med. 2014;108(12):1752–1760. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donohue JF, Maleki-Yazdi MR, Kilbride S, Mehta R, Kalberg C, Church A. Efficacy and safety of once-daily umeclidinium/vilanterol 62.5/25 mcg in COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107(10):1538–1546. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use. ICH harmonised tripartite guideline: guideline for good clinical practice E6(1) 1996. [Accessed January 4, 2017]. [cited May 2013]. Available from: https://www.ich.org/fileadmin/Public_Web_Site/ICH_Products/Guidelines/Efficacy/E6/E6_R1_Guideline.pdf.

- 10.World Medical Association [webpage on the Internet] WMA Declaration of Helsinki – Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. 2013. [Accessed January 4, 2017]. [cited May 2013]. Available from: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html.

- 11.Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004;23(6):932–946. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boehringer Ingelheim [webpage on the Internet] SPIRIVA® HANDIHALER® summary of product characteristics. 2004. [Accessed April 16, 2016]. Available from: https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/10039.

- 13.Boehringer Ingelheim, SPIRIVA® HANDIHALER® [prescribing information] 2004. [Accessed April 16, 2016]. Available from: http://docs.boehringer-ingelheim.com/Prescribing%20Information/PIs/Spiriva/Spiriva.pdf.

- 14.Mahler DA, Witek TJ., Jr The MCID of the transition dyspnea index is a total score of one unit. COPD. 2005;2(1):99–103. doi: 10.1081/copd-200050666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones PW. St. George’s respiratory questionnaire: MCID. COPD. 2005;2(1):75–79. doi: 10.1081/copd-200050513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kon SS, Canavan JL, Jones SE, et al. Minimum clinically important difference for the COPD Assessment Test: a prospective analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2(3):195–203. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calzetta L, Rogliani P, Matera MG, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis of dual bronchodilation with LAMA/LABA for the treatment of stable COPD. Chest. 2016;149(5):1181–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.02.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bateman ED, Ferguson GT, Barnes N, et al. Dual bronchodilation with QVA149 versus single bronchodilator therapy: the SHINE study. Eur Respir J. 2013;42(6):1484–1494. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00200212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siler TM, Kerwin E, Sousa AR, Donald A, Ali R, Church A. Efficacy and safety of umeclidinium added to fluticasone furoate/vilanterol in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results of two randomized studies. Respir Med. 2015;109(9):1155–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Calverley PM, Rennard SI. What have we learned from large drug treatment trials in COPD? Lancet. 2007;370(9589):774–785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cope S, Donohue JF, Jansen JP, et al. Comparative efficacy of long-acting bronchodilators for COPD: a network meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2013;14:100. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-14-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(8):775–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Celli B, Crater G, Kilbride S, et al. Once-daily umeclidinium/vilanterol 125/25 mcg in COPD: a randomized, controlled study. Chest. 2014;145(5):981–991. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, et al. A 4-year trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(15):1543–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oba Y, Sarva ST, Dias S. Efficacy and safety of long-acting beta-agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonist combinations in COPD: a network meta-analysis. Thorax. 2016;71(1):15–25. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Serial LS mean change (95% CI) from baseline in FEV1 over 0–3 h on Day 28 (A) and Day 56 (B; ITT population).

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least squares; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

Table S1.

Additional lung function outcomes (ITT population)

| Outcome measure | UMEC/VI (N=247) |

TIO (N=247) |

|---|---|---|

| Trough FVC (L) | ||

| Day 2 | ||

| na | 238 | 238 |

| LS mean (SE) | 131 (18.3) | 6 (18.3) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 125 (74–176)*** | |

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 237 | 230 |

| LS mean (SE) | 56 (20.5) | −4 (20.7) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 59 (2–116)* | |

| Day 56 | ||

| na | 232 | 226 |

| LS mean (SE) | 36 (20.6) | −23 (20.8) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 59 (2–117)* | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 226 | 229 |

| LS mean (SE) | 47 (22.7) | −50 (22.7) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 97 (34–160)** | |

| Day 85 | ||

| na | 224 | 225 |

| LS mean change (SE) | 63 (22.6) | −41 (22.6) |

| Difference (95% CI) | 104 (41–166)** |

Notes:

P<0.05.

P<0.01.

P<0.001.

Number of subjects with analyzable data at the current time point.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FVC, forced vital capacity; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least squares; SE, standard error; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.

Table S2.

Patient reported outcome responder analyses (ITT population)

| Outcome measure | UMEC/VI (N=247) |

TIO (N=247) |

|---|---|---|

| TDI score responder analysis | ||

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 240 | 245 |

| Responder,b n (%) | 139 (58) | 112 (46) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.67 (1.14–2.45)** | |

| Day 56 | ||

| na | 240 | 245 |

| Responder,b n (%) | 136 (57) | 124 (51) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.25 (0.85–1.84) | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 240 | 245 |

| Responder,b n (%) | 151 (63) | 121 (49) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.78 (1.21–2.64)** | |

| SGRQ total score responder analysis | ||

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 237 | 244 |

| Responder,c n (%) | 99 (42) | 100 (41) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.05 (0.73–1.53) | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 242 | 245 |

| Responder,c n (%) | 104 (43) | 117 (48) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 0.83 (0.58–1.19) | |

| CAT score responder analysis | ||

| Day 28 | ||

| na | 247 | 247 |

| Responder,d n (%) | 118 (48) | 99 (40) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.40 (0.96–2.04) | |

| Day 84 | ||

| na | 247 | 247 |

| Responder,d n (%) | 121 (49) | 111 (45) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | 1.17 (0.81–1.70) | |

Notes:

P<0.01.

Number of subjects with analyzable data at the current time point.

Defined as a ≥1-unit improvement from baseline.

Defined as a ≥4-unit improvement from baseline.

Defined as a ≥2-unit improvement from baseline.

Abbreviations: CAT, COPD Assessment Test; ITT, intent-to-treat; LS, least squares; SE, standard error; SGRQ, St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire; TDI, Transition Dyspnea Index; TIO, tiotropium; UMEC, umeclidinium; VI, vilanterol.