Abstract

Background

Self-medication patterns vary among different populations, and are influenced by many factors. No review has been done that comprehensively expresses self-medication practice in Ethiopia. The aim of this study was to provide an overview of the literature on self-medication practice in Ethiopia.

Materials and methods

Databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and Hinari) were searched for published studies on the practice of self-medication in Ethiopia without restriction in the year of publication or methodology. Some studies were also identified through manual Google search. Primary search terms were “self medication”, “Ethiopia”, “self care”, “non-prescription”, “OTC drug use”, “drug utilization”, and “drug hoarding”. Studies that measured knowledge only or attitude only or beliefs only and did not determine the practice of self-medication were excluded.

Results

The database search produced a total of 450 papers. After adjustment for duplicates and inclusion and exclusion criteria, 21 articles were found suitable for the review. All studies were cross-sectional in nature. The prevalence of self-medication varied from 12.8% to 77.1%, with an average of 36.8%. Fever/headache, gastrointestinal tract diseases, and respiratory diseases were the commonest illnesses/symptoms for which self-medication was taken. The major reasons for practicing self-medication were previous experience of treating a similar illness and feeling that the illness was mild. Analgesics/antipyretics, antimicrobials, gastrointestinal drugs, and respiratory drugs were the common drug classes used in self-medication. Mainly, these drugs were obtained from drug-retail outlets. The use of self-medication was commonly suggested by pharmacy professionals and friends/relatives.

Conclusion

Self-medication practice is prevalent in Ethiopia and varies in different populations and regions of the country. Some of the self-medication practices are harmful and need prompt action. Special attention should be given to educating the public and health care providers on the types of illnesses that can be self-diagnosed and self-treated and the types of drugs to be used for self-medication.

Keywords: self-medication, self-care, OTC drug, Ethiopia

Introduction

Measures taken to achieve well-being and freedom from illness are different based on the attitudes and experiences of individuals. Beliefs, feelings, and thoughts of an individual significantly influence his/her understanding of an illness, which in turn affects the decision taken to address it.1 A small proportion, around 10%–30%, of symptoms experienced by an individual are brought to the attention of a physician. The majority of symptoms are either tolerated or self-medicated.2 According to the World Health Organization, self-medication is the selection and use of medicines by individuals to treat self-recognized illnesses or symptoms.3

Self-medication is a fairly widespread practice worldwide. Both developed and developing nations are giving due attention to self-medication as a component of their health care policy.4–9 Studies have revealed that increases in self-medication are due to a number of factors. These include socioeconomic factors, lifestyle, ready access to drugs, increased potential to manage certain illnesses through self-care, and greater availability of medicinal products. In most economically deprived countries, including Ethiopia, many drugs are dispensed over the counter (OTC), and the majority of health-related problems, nearly 60%–80%, are treated through self-medication as a lower-cost alternative.10–13

When practiced correctly, self-medication has a positive impact on individuals and health care systems. It allows patients to take responsibility and build confidence to manage their own health, thereby promoting self-empowerment. Furthermore, it can save time spent in waiting for a doctor and even lives in acute conditions, and may contribute to decreasing health care costs.14 If used appropriately, self-medication can lighten the demand on doctors and make people more health-conscious.15 The World Health Organization has also pointed out that responsible self-medication can help to prevent and treat ailments that do not require medical consultation, and provides a cheaper alternative for treating common illnesses.6

Regardless of the unquestionable benefits obtained from self-medication with nonprescription drugs, there are undesired outcomes that occur, due to improper usage. These have been indicated in studies where self-medication may have carried risks of misdiagnosis, use of too high a dose, incorrect duration of use, and adverse drug reactions related to the improper use of OTC drugs.16,17 Inappropriate self-medication results in irrational use of drugs, wastage of resources, increased risk of unwanted effects, and prolonged suffering.18 Irrational usage of antibiotics leads to the emergence of resistance pathogens worldwide.19 Furthermore, risks associated with self-medication also include potential delay in treating serious medical conditions, masking of symptoms of serious conditions through the use of nonprescription products, and increased polypharmacy and interaction with other regularly used medications.5 Even though self-medication is difficult to eliminate, interventions can be made to discourage the abnormal practice. Increasing self-medication practice requires more and better education of both the public and health professionals to avoid irrational use of drugs.10,20 All parties involved in self-medication should be aware of the benefits and risks of any self-medication product.6

Self-medication patterns vary among different populations, and are influenced by many factors, such as age, sex, income, expenditure, self-care orientation, education level, medical knowledge, satisfaction, and perception of illnesses.14 The type and extent of self-medication and the reasons for its practices may also vary from country to country.

Even though various studies have been conducted on self-medication practices in different parts of Ethiopia, there has not been any review done that comprehensively expresses self-medication practice in the country. Therefore, there is a need to know the overall situation of self-medication practice in the country, in order to devise appropriate educational, regulatory, and administrative measures in alleviating public health risks arising from improper practices of self-medication. The objective of this review was to provide an overview of the literature on self-medication practice among the Ethiopian population. It gives a comprehensive account of self-medication, more specifically its prevalence, common illnesses that cause the use of self-medication, commonly used drugs in self-medication, common reasons to practice self-medication, source of drugs for self-medication, and factors associated with the practice of self-medication.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

Databases (PubMed, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and Hinari) were searched for published studies done on the practice of self-medication in Ethiopia. Some studies were also identified through a manual Google search. Additional articles were also searched from the reference lists of retrieved articles. No restriction was applied on the year of publication, methodology, or study subjects. Primary search terms were “self medication”, “self care”, “non-prescription”, “OTC drug use”, “drug utilization”, “drug hoarding”, and “Ethiopia”.

Article selection

Studies were included in the review if they aimed to assess self-medication practice in Ethiopia. Studies that measured knowledge only or attitudes only or beliefs only and did not determine the practice of self-medication were excluded.

Assessment of methodological quality

Methodological validity of all the 21 studies was checked prior to inclusion in the review by undertaking critical appraisal using a standardized instrument adapted from Guyatt et al.21 The instrument has eleven criteria. Each study was evaluated for each criterion/question as “yes”, “cannot tell”, or “no”, with values of 2, 1, and 0 assigned, respectively. Studies with a total score of more than 90% were considered to be of high quality, 75%–90% medium quality, and below 75% low quality.

Data abstraction

The author screened the articles based on the inclusion/ exclusion criteria. The following details were extracted from each study using an abstraction form: author, year of publication, study area, study subjects, sample size, study design, sampling technique, recall period, prevalence of self-medication, common illnesses that resulted in the use of self-medication, drugs used in self-medication, reasons to practice self-medication, and factors associated with self-medication.

Results

Literature search results

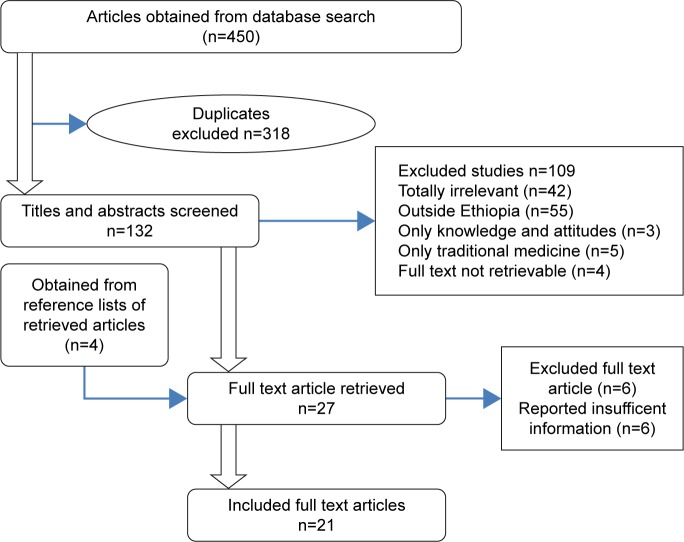

The search of the PubMed, Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and Hinari databases and Google provided a total of 450 studies. After adjustment for duplicates, 132 remained. Of these, 105 studies were discarded, since after review of their titles and abstracts, they did not meet the criteria. Four studies were discarded as their full text was not available. The full texts of the remaining 23 studies were reviewed in detail. Six studies were discarded after the full text had been reviewed, since they did not address much of the needed information. An additional four studies that met the criteria for inclusion were identified through searching the reference lists of retrieved papers. Finally, as shown in Figure 1, 21 studies were included in the review.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Study characteristics

The 21 studies differed substantially in sample size, recall period, and location. From these 21 articles, the majority were conducted to assess the self-medication practice of any drug or disease, while three studies focused on self-medication with antibiotics and antimalarials only. Ten studies assessed self-medication practices at the community level, five assessed self-medication practices of university students, and four assessed self-medication practices of drug-retail outlet customers. Two studies reported self-medication practices of pregnant women who were on antenatal care follow-up. The studies were conducted in different parts of the country on samples of 237–10,170 individuals. All the studies were cross-sectional in nature. The majority of the studies used stratification and random sampling to select study subjects. Detailed description of the characteristics of individual studies is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Study | Area | Subjects | Design | Sample size | Sampling technique |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abay and Amelo71 | Gondar University, northwest Ethiopia | Medical, pharmacy, and health science students | Cross-sectional | 414 students | Stratified sampling followed by random sampling |

| Tenaw and Tsige73 | Addis Ababa, central Ethiopia | Customers of community pharmacies | Cross-sectional | 918 respondents from 24 community pharmacies | Multistage stratified sampling followed by convenience sampling |

| Worku and Mariam10 | Jimma, southwest Ethiopia | Residents of Jimma town | Community-based cross-sectional survey | 352 respondents | Systematic random sampling |

| Ararsa and Bekele74 | Jimma, southwest Ethiopia | Private pharmacy clients | Community-based cross sectional study | 398 clients | Systematic random sampling |

| Befekadu et al68 | Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Jimma, southwest Ethiopia | Pregnant women attending antenatal care | Hospital-based cross- sectional study | 315 pregnant women | Random sampling |

| Jaleta et al75 | Sire town, west Ethiopia | Inhabitants of Sire town | Community based cross-sectional study | 423 households | Systematic random sampling |

| Abrha et al76 | Kolladiba town, northwest Ethiopia | Heads of households | Community based cross-sectional study | 261 respondents | Systematic random sampling |

| Eticha and Mesfin6 | Mekelle, north Ethiopia | People who came to community pharmacies for self-medication | Cross-sectional study | 270 clients | Convenience sampling |

| Mossa et al13 | Worabe town of Silte Zone, south Ethiopia | Residents of Worabe town | Community-based cross-sectional survey | 405 households | Multistage stratified sampling followed by random sampling |

| Bekele et al70 | Arsi University, Asella | Health science students | Cross-sectional study | 548 students | Stratified sampling followed by random sampling |

| Mihretie15 | Bahir Dar, northwest Ethiopia | Urban dwellers of Bahir Dar town | Community-based cross-sectional survey | 595 households | Two-stage cluster sampling followed by random sampling |

| Abeje et al69 | Bahir Dar, northwest Ethiopia | Pregnant mothers attending antenatal care | Institution-based cross-sectional study | 510 pregnant women | Multistage stratified sampling followed by systematic random sampling |

| Deressa et al77 | Butajira, southern Ethiopia | Rural communities of Butajira | Cross-sectional study | 630 households with malaria cases | Simple random sampling |

| Sado and Gedif78 | Nekemte town and surrounding rural areas, western Ethiopia | Household heads | Cross-sectional study | 820 household heads | Cluster sampling followed by systematic random sampling |

| Hailemichael et al72 | Harar, eastern Ethiopia | Harar Health Sciences College students | Institution-based cross-sectional study | 237 students | Two-step stratified sampling followed by simple random sampling techniques |

| Angamo and Wabe5 | Jimma, southwest Ethiopia | Medical sciences students in Jimma University | Cross-sectional study | 403 students | Random sampling |

| Gutema et al11 | Mekelle, north Ethiopia | Health sciences students of Mekelle University | Cross-sectional study | 283 students | Two-stage stratified random sampling methods |

| Ali et al79 | Addis Ababa, central Ethiopia | Private pharmacy customers seeking self- medication | Cross-sectional survey (quantitative and qualitative) | 400 clients | NR |

| Suleman et al80 | Asendabo, southwest Ethiopia | Residents of Asendabo town | Community-based cross-sectional study | 1,257 individuals (242 households) | Systematic random sampling |

| Gedif81 | Butajira, southern Ethiopia | Residents of Butajira town | Community-based cross-sectional study | 4,861 households | Random sampling |

| Abula and Worku2 | Gondar, Kolladuba, and Debark towns, northwest Ethiopia | Residents of Gondar, Kolladuba, and Debark towns | Community-based cross-sectional survey | 10,170 individuals (1,880 households) | Systematic random sampling |

Abbreviation: NR, not reported.

Methodological quality of included studies

Critical appraisal showed most studies were of high quality (n=18, 85.7%), whereas three (14.3%) were of medium quality. No difference was observed in terms of self-medication prevalence between high- and medium-quality studies.

Prevalence of self-medication

Of the 21 studies reviewed, 16 reported on prevalence of self-medication. Four studies did not calculate prevalence, since their subjects were community-pharmacy customers who came for self-medication. The reported prevalence of self-medication in the studies varied from 12.8% (Bahir Dar town residents) to 77.1% (Arsi University health science students), with an overall prevalence of 36.8%. The prevalence of self-medication in the studies was determined based on the illness history for different recall periods (2 weeks to 6 months). Two-week recall periods were used in many studies. There was no difference in the prevalence of self-medication in studies with small and large sample sizes. The prevalence of self-medication with respective recall period for each of the studies is indicated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Prevalence of self-medication

| Study | Subjects | Recall period | Prevalence of self-medication in those who faced an illness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abay and Amelo71 | Medical, pharmacy, and health science students | 2 months | 38.5% |

| Worku and Mariam10 | Residents of Jimma town | 1 month | 27.6% |

| Befekadu et al68 | Pregnant women attending antenatal care | During current pregnancy | 20.1% |

| Jaleta et al75 | Inhabitants of Sire town | 2 weeks | 27.16% |

| Abrha et al76 | Head of households | 2 weeks | 62.8% |

| Mossa et al13 | Residents of Worabe town | 3 months | 16.9% |

| Bekele et al70 | Health science students | 3 months | 77.1% |

| Mihretie15 | Urban dwellers of Bahir Dar town | 2 weeks | 12.8% |

| Abeje et al69 | Pregnant mothers attending antenatal care | During the current pregnancy | 36% |

| Sado and Gedif78 | Household heads | 1 month | 35% |

| Hailemichael et al72 | Harar Health Sciences College students | NR | 62% |

| Angamo and Wabe5 | Medical sciences students in Jimma University | 2 months | 45.89% |

| Gutema et al11 | Health Sciences students of Mekelle University | 3 months | 43.24% |

| Suleman et al80 | Residents of Asendabo town | 2 weeks | 39% |

| Gedif81 | Residents of Butajira town | 2 weeks | 17% |

| Abula and Worku2 | Residents of Gondar, Kolladuba, and Debark towns | 2 weeks | 27.5% |

Abbreviation: NR, not reported.

Common illnesses that cause self-medication, reasons to practice self-medication

Fever/headache, gastrointestinal (GI) tract diseases, and respiratory diseases were the commonest illnesses or symptoms for which self-medication was taken, accounting for an average of 30.5%, 19.7%, and 18.3% of self-medication use, respectively. The major reasons to practice self-medication were previous experience of treating a similar illness, feeling that the illness was mild and did not require the service of a physician, less expensive in terms of time and money, and need for emergency use. Table 3 shows the illnesses that resulted in self-medication and reasons that drove people to practice self-medication as reported in each study.

Table 3.

Common illnesses leading to self-medication, reasons to practice self-medication, and factors associated with self-medication

| Study | Illnesses | Reasons | Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abay and Amelo71 | Fever and headache 24.8% Respiratory diseases 23.9% Gastrointestinal tract diseases 13.2% Diarrhea 8.9% Malaria 6.1% Pneumonia 6.1% Constipation 5.6% Eye disease 3.8% |

Prior experience 35.4% Minor illness 30.5% Less costly 9.8% Emergency use 15.8% |

Year of study (in which prevalence of self-medication increases) |

| Tenaw and Tsige73 |

Gastrointestinal 25.1% Headache/fever 24.9% Respiratory problems 21.4% Skin diseases/injuries 8.4% Eye infections/inflammations 7.1% Sexually transmitted diseases 2.6% |

Minor illness 36.6% Emergency use 19.8% Prior experience 18.2% Less costly 12.6% For prevention of illness 11.2% |

NR |

| Worku and Mariam10 |

Headache 13.2% Fever 21.7% Cough 21.7% Diarrhea 6.5% Abdominal pain 10.5% Dyspnea 1.3% |

Less costly 35.7% Minor illness 33.3% Less waiting time 19.1% Prior experience 9.5% |

NR |

| Ararsa and Bekele74 | NR | Previous experience 30.16% Less costly 31.75% Minor illness 25.4% Emergency 6.35% |

NR |

| Befekadu et al68 | Cough 13.1% Typhoid 14.8% Headache 47.5% Common cold 1.6% Diarrhea 3.3% Anemia 13.1% Asthma 6.6% |

Time-saving 44.3% Easily available 57.4% Know about drug and illness 13.2% |

Self-medication experience (P=0.001) Maternal education (P=0.03) Age of respondents (P=0.005) Number of children (P=0.001) Place of residence (P=0.007) |

| Jaleta et al75 | Headache 10.29% Fever 5.35% Cough or common cold 3.29% Diarrhea 3.29% |

Less costly 31.82% Emergency use 22.73% Previous experiences 13.64% |

No significant association |

| Abrha et al76 | Headache or fever 30.9% Respiratory tract infection 23.2% Gastrointestinal disease 21.8% Malaria 8.7% |

Less costly 44.5% Minor illness 31.1% Remoteness of health care facilities 1.2% Repetitiveness of symptoms 11.6% To save time 4.3% No benefit from modern health care 7.3% |

NR |

| Eticha and Mesfin6 | Headache or fever 20.7% Gastrointestinal disease 17.3% Respiratory tract infection 15.9% Eye disease 14% Skin disease/injury 13.1% Dysmenorrhea 11.3% |

Emergency use 17% Minor illness 21.7% Prevention of illness 16.9% Prior experience 20.7% Less costly 20.2% |

NR |

| Mossa et al13 | Headache 38.5% Fever 35.9% Cough 14.1% Diarrhea 10.2% Abdominal pain 10.2% Joint and back pain 35.9% Nausea and vomiting 8.5% |

Less costly 7.7% Minor illness 19.2% Avoiding waiting time 33.3% Distance of health facility 9% Emergency case 16.7% |

Monthly income (P=0.006) (the higher the income, the more self-medication practice) Level of education (P=0.000) (self-medication practice increases as the level of education increases) |

| Bekele et al70 | Headache/fever 56.5% Gastrointestinal disease 34.1% Respiratory tract infection 31.8% Eye disease 22.4% Skin diseases or injury 17.4% Sexually transmitted disease 10.4% Maternal/menstrual 29.2% |

Disease not serious 44.1% Poor quality of service 27.1% Emergency use 24.7% Prior experience 23.4% Took pharmacology course 21.1% Saves time 20.3% Less expensive 19.4% |

Sex (female) Field of study (midwives) Positive attitude for self-medication |

| Mihretie15 | Respiratory tract disease 58.8% Diarrhea 41.2% Fever 17.6% Headache 11.8% Gastrointestinal tract disease 5.9% |

Previous experience 82.2% Minor problem 17% Less costly 11.8% Emergency use 5.9% |

No significant associations |

| Abeje et al69 | NR | Less costly 6.25% Minor illness 22.6% Saves time 11.7% Prior experience 48.4% |

Gravida (multigravida) (P<0.05) Maternal illness (current illness) (P<0.05) Location of antenatal care service (rural) (P<0.05) |

| Deressa et al77 | Malaria 100% (study done on self-treatment of malaria only) | Prior experience 50.9% Less costly 23.6% Saves time 10.9% Peer influence 5.5% Minor illness 1.8% Dissatisfaction with health services 1.8% |

NR |

| Hailemichael et al72 | Headache or mild pain 47.3% Gastrointestinal problems 30.8% Eye and ear symptoms 29.1% Vomiting 6.3% |

Knowledge about the disease/drug 37% Time-saving 29% Less costly 19% Increase in confidence 19% |

Student’s year of study (as study year increased, prevalence of self-medication increased) |

| Angamo and Wabe5 | Headache 36.85% Abdominal pain 30.55% Cough 23.16% Fever 6.32% |

Prior experience 46.32% Minor illness 25.26% Time-saving 24.21% Low cost 4.21% |

NR |

| Gutema et al11 | Headache 51.56% Cough and common cold 44.8% Dysmenorrhea (painful menses) 20.3% Dyspepsia/heartburn 17.2% Fever 14.1% Diarrhea 10.9% Constipation 9.4% Cough and chest pain (like pneumonia) 7.8% Skin problems 3.13% |

Prior experience 39.1% Mildness of illness 37.5% Time-saving 15.6% Less costly 4.7% Lack of interest in medical services 1.56% |

Sex (female) Specific field of study (pharmacy students practiced self-medication more frequently than medical and other paramedical students) Study year (increases with year of study) |

| Ali et al79 | Respiratory symptoms 22.8% Gastrointestinal symptoms 18% Abdominal pain 17% |

Prior experience 61.8% Advised by pharmacists 24.8% Others use for similar cases 18.3% Know about it 12.3% |

NR |

| Suleman et al80 | Fever 40.6% Headache 23.1% Cough and cold 11.2% Eye disease 4.2% Gastric pain 4.2% Diarrhea 3.5% Abdominal pain 2.1% |

Less costly 10.7% Minor illness 41.1% Saves time 12.5% Remoteness of health care facility 12.5% Low quality of modern health care 23.2% |

NR |

| Gedif81 | Headache 22.1% Fever 20.8% Diarrhea 10.3% Malaria 9% Eye disease 8.7% Respiratory tract complaints 8.4% |

Minor illness 25.2% Prior experience 23.5% Neighbors/relatives recommend 20% Less costly 11.3% |

Ethnicity (Meskan subgroup) |

| Abula and Worku2 |

Cough and cold 23.9% Fever 9.5% Headache 8.5% Gastric pain 8.3% Diarrhea 5.6% Eye disease 5.4% |

Less costly 37.4% Minor illness 29.9% Saves time 14.8% Less benefit from health institution 13.6% Remoteness of modern health care 4.3% |

NR |

Abbreviation: NR, not reported.

Drugs used in self-medication, where they are obtained, and who suggested their use

As indicated in Table 4, analgesics/antipyretics, antimicrobials, GI drugs, and respiratory drugs were the common drug classes used in self-medication. On average, 38.7%, 30.8%, 16.7%, and 7.3% of people who practice self-medication used these drugs, respectively. Mainly, these drugs were obtained from drug-retail outlets (66.6%), shops (10.3%), relatives/friends (9.3%), and left over from previous use (6.5%). The use of self-medication was commonly suggested by pharmacy professionals, friends/relatives, and clinicians, but without formal prescriptions.

Table 4.

Drugs used in self-medication, where they are obtained, and who suggests their use

| Study | Drugs | Source | Suggested by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abay and Amelo71 | Paracetamol 46.3% Analgesics 24.4% Antacids 12.2% Anthelmintics 10.9% Antibiotics 4.8% Antimalarials 3.7% |

Pharmacy or drug shop 72% Friends 5.9% Drugs left over from prior use 3.6% Home remedies 8.5% |

Reading material 30.5% Advice from pharmacist 25.6% Advice from friend 19.5% Advice from clinician without prescription 13.4% Advice from traditional healers 3.7% |

| Tenaw and Tsige73 | Analgesics/antipyretics 33.1% Antimicrobials 26.4% Gastrointestinal drugs 17.7% Respiratory drugs 9.7% Oral rehydration salts 0.6% |

DROs (study subjects those who came to community pharmacies) | Clinicians, but without formal prescriptions 39% Friends, relatives, or neighbors 23.5% Pharmacy professionals 15.4% Labels, leaflets, or promotional materials 20% |

| Worku and Mariam10 | NR | DROs 52.4% Open market 19% Left over from past prescription 11% Neighbor 9.6% Kiosk 7.1% |

NR |

| Ararsa and Bekele74 | Analgesics/antipyretics 28.94% Antimicrobials 28.13% Anthelmintics 17.56% Gastrointestinal drugs 15.2% |

DROs (study subjects those who came to community pharmacies) | Drug outlets 48.2% Previous experience 30.52% Other health professional 11.25% Friend 6.83% |

| Befekadu et al68 | Paracetamol 41% Aspirin 14.7% Chloramphenicol 13.1% Iron 11.5% Tetracycline 4.9% Amoxicillin 6.6% Cough syrup 9.8% salbutamol 6.6% |

Private drug-retail outlets 85.2% Neighbors/friend 19.1% Shops 14.8% |

Client 39.3% Pharmacist/druggist 34.4% Husband 18% Neighbor 4.9% |

| Jaleta et al75 | Analgesics 40.96% Antibiotics 24.1% Traditional medicine 20.48% Antimalarials 4.81% Anthelmintics 3.61% |

Drug-retail outlets 84.84% Neighbors 9.09% Left over from past prescription 6.06% |

Dispensers 40.48% Previous experience 39.29% Health professional other than dispensers 10.71% Neighbors 9.52% |

| Abrha et al76 | Analgesics/antipyretics 34.1% Antibiotics 24.7% Gastrointestinal drugs 22.4% Antimalarial drugs 8.2% |

Drug vendor and pharmacy 69.5% Shops 16.5% Leftover drugs from previous illness 8.1% Neighbors and relatives 5.9% |

NR |

| Eticha and Mesfin6 | Analgesics/antipyretics 20.8% Gastrointestinal drugs 17.5% Respiratory drugs 14.9% Oral rehydration salts 14.2% Vitamins 11.1% Antimicrobials 8.4% |

NR | Pharmacy professionals 22.9% Clinicians without formal prescriptions 20.6% Friends, neighbors, or relatives 18.5% Labels, leaflets, or promotional materials 12.8% Traditional healers 12.5% |

| Mossa et al13 | Antibiotics 61.53% Antimalarials 38.02% Traditional medicine 26.92% |

Neighbors 5.1% Left over from past prescription 7.7% Kiosks 17.9% Drug-retail outlet 59% |

NR |

| Bekele et al70 | Antibiotics 59.9% Analgesics/antipyretics 47.8% Gastrointestinal drugs 28.8% Drugs for RTIs 24.7% Vitamins 22.1% ORS 16.7% |

Drug-retail outlets 61.5% Shop/supermarkets 29.8% Relatives/friends 24.1% Left over from previous use 19.1% |

Own experience 51.5% Pharmacy professionals 32.8% Previous prescription 27.1% Friends 21.4% Family 17.1% |

| Mihretie15 | Amoxicillin 61.1% Cotrimoxazole 27.8% Ampicillin 11.1% Ciprofloxacin 5.6% This study assessed self-medication practices with antibiotics only |

Drug-retail outlet 82.4% Friends or relatives 17.6% |

Physician/nurse 11.8% Pharmacist 82.4% Friends or relatives 17.6% Reading 11.8% |

| Abeje et al69 | NR | Pharmacy/drug shop 56.2% Leftover drugs 16.4% Friends/relatives 4.7% Self-prescribed herbal preparations 30.5% Market areas 2.3% |

NR |

| Deressa et al77 | Chloroquine 54.8% Sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine 43.2% Primaquine 3% (self-treatment of malaria only) |

Malaria-control program 47.6% Private clinic 26.8% Health post 20.5% Health center 17.5% Pharmacy 5.9% Health station 2.1% Market or any shop 1.4% Drug shop 1% |

NR |

| Sado and Gedif78 | Antibiotics 33% Anti-inflammatories/analgesics 32% Gastrointestinal tract drugs 17% Cough preparations 2% |

NR | NR |

| Hailemichael et al72 | Antibiotics 47% Painkillers 37% Vitamins and minerals 10% Cough syrup 7% |

NR | Previous prescription 33.9% Pharmacist 24.6% Textbooks/internet 21.6% Friends/family 16.9% |

| Angamo and Wabe5 | Analgesics 49.38% Antimicrobials 35.8% Antacids 7.41% |

Drug outlets 92.63% Shops/supermarkets 3.16% Relatives/friends 3.16% Leftover medicines 1.05% |

Individual respondents themselves 34.74% Family 27.37% Friends 20.00% Health professionals 17.89% |

| Gutema et al11 | Paracetamol 48.4% NSAIDs 42.2% Antibiotics 17.2% Cough syrup 12.5% Antacids 7.8% Topical agents 4.7% Herbal remedies 4.7% Anthelmintics 4.7% |

Drug-retail outlet 40.63% Friend/relative 15.63% Open market 14.1% Drug leftovers 7.8% Traditional medicine 7.8% Kiosk (small shops) 1.56% |

Self-decision 64% Family/friends 31.25% Media and reading material 14.1% Pharmacist/druggist 9.4% Prescribers without prescription 7.8% |

| Ali et al79 | Antibiotics 35.5% Gastrointestinal medicines 19.3% Respiratory drugs 15.3% |

NR | NR |

| Suleman et al80 | NR | Home remedies 17.5% Drug outlets 5.6% Private clinics 5.6% Shops 4.2% Past prescription leftovers 3.5% Market 2.1% Neighbors 0.7% |

NR |

Abbreviations: DROs, drug retail outlets; NR, not reported; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; RTIs, respiratory tract infections; ORS, oral rehydration salt.

Factors associated with practice of self-medication

Even though most of the studies reviewed did not address factors associated with self-medication, some checked the presence of association between sociodemographic characteristics and self-medication practice. As shown in Table 3, age, place of residence, sex, educational status, occupation, income, ethnicity, prior self-medication experience, attitude toward self-medication, year of study, and field of study of students were some of the factors identified in the reviewed studies.

Discussion

The prevalence of self-medication varied across the studies reviewed, ranging from 12.8% to 77.1%. This variation was found to depend on recall periods used in each study. Average prevalence rates of 31%, 31.3%, 42.2%, and 45.7% were reported for studies that assessed self-medication practice with 2-week, 1-month, 2-month, and 3-month recall periods, respectively. The main reasons for the wide variation in the prevalence of self-medication practice may be differences in social determinants of health, beliefs, and culture of the population, as Ethiopia is a country of multiple “nations”. The difference in approaches used to collect information about self-medication may also have contributed to this variation in prevalence of self-medication. Similarly, review article by Shehnaz et al reported that the overall prevalence of self-medication varied from 2% to 92%.22

Higher self-medication use was reported in studies conducted on health science students than the general population. This may be because health science students have better knowledge of disease and drugs, so have less inclination to seek physicians help to treat their illnesses. Other studies conducted on health science students in different parts of the world have also reported higher prevalence of self-medication practice.23–25 Martins et al also reported community members with a high level of education were more likely to use antimicrobial self-medication, possibly due to the exposure and increased focus on health.26

The most common reasons for self-medication in Ethiopia were previous experience of treating a similar illness, feeling that the illness was mild, less costly, and less time-consuming. Similarly, the patient’s assessment of their ailment as minor was identified as one of the major factors in self-medication in many studies conducted outside Ethiopia.27–35 Prior experience of treating the same condition by self-medication has also been mentioned as the main reason for practicing self-medication.34,35 Studies conducted in other developing countries also mention lack of time to visit the physician and economic problems as the main reason to use self-medication.23,33

Fever/headache, GI-tract diseases, and respiratory diseases were the commonest illnesses/symptoms for which self-medication was taken. Fever and headache were indicated as the most frequent health complaint that led to self-medication in different studies.22–24,35–37 There were also studies that reported respiratory diseases23,34,35,37–39 and GI-tract diseases23,40 as common illnesses for which self-medication was used. This may be because these illnesses are very common and occur frequently in individuals with experience of treating them. The mild and self-limiting nature of these illnesses may also prevent patients from seeking physician consultation. However, patients should not forget that when these illnesses/symptoms occur repeatedly or for prolonged periods, they should be investigated further by physicians, as they may be manifestations of serious illnesses.

Analgesics/antipyretics, antimicrobials, GI drugs, and respiratory drugs were the most frequently used drug classes in self-medication. Multiple studies conducted to assess the practice of self-medication outside Ethiopia also reported analgesics as the most widely consumed OTC drugs in self-care.22,23,35,40–43 Antimicrobials were also reported in many studies as commonly used drugs in self-medication.23,34,37,44–46 One review article indicated that the overall estimate of antimicrobial self-medication in low- and middle-income countries was 38.8%.47 Even though every medication used in self-care needs responsibility, the high rate of antimicrobial use in self-medication needs special emphasis. Despite their prescription-only legal status in most countries, antibiotic use as an OTC medication occurs globally.48 This practice poses great risks, like antibiotic resistance. The practice of self-medication should be conducted only insofar as the benefits outweigh the risks. It should also be understood that the potential benefits of self-medication will only be obtained if it is practiced responsibly.49 Responsible government and nongovernment organizations should work hard to ensure the rational use of antimicrobials.

Common sources of drug recommendation included pharmacy professionals, friends/relatives, and clinicians, but without formal prescriptions. It was also mentioned in different studies that community drug sellers were commonly used as a source of advice or information for the drugs used in self-medication.23,34,35,47,50,51 The advice of friends or family was also reported as a commonly used source to identify drugs used for self-medication.23,24,34,51 As most of the self-medication users take drugs after consulting drug dispensers, the main role of assuring the rationality of self-medication practice will primarily lay on them. As such, they should be well trained to respond to symptoms. They should also have professional conduct, and abide by the rules and regulations of the drug-control authority of the country. They should avoid the nonprescription sale of prescription-only drugs. The community should also be educated on which illnesses they can seek drugs without the advice of a physician and for which they have to seek a clinician’s consultation.

Drugs used in self-medication were mostly obtained from drug-retail outlets (66.6%), shops (10.3%), relatives/friends (9.3%), and left over from previous use (6.5%). According to the current study, more than 10% of self-medication users in Ethiopia take drugs from shops. This is another important issue that needs due attention. Drugs should not be allowed to be present in shops, since they need special storage conditions, special handling, and advice from a pharmacy professional who is knowledgeable on dispensing. Even though Ethiopian law forbids the availability of drugs in shops, the implementation of regulation is weak. Ethiopian food, medicine, and health care control authorities need to enforce this law more judiciously.

There were several studies that reported significant associations between self medication practice and sociodemographic characteristics such as age,52–59 sex,34,52,56,57,60–63 educational status,58,62,64–66 income,58,62,64–66 and prior self-medication experience.62,67 Similarly, the current review identified some sociodemographic factors to affect the prevalence of self medication. These were age,68 place of residence,68,69 sex,11,70 educational status,13,68 income,13 prior self-medication experience,68 attitude toward self-medication,70 student’s year of study,11,71,72 field of study,11,70 and ethnicity.81

Limitations

Even though this review has its own strengths, such as inclusion of both published and unpublished research works and critically appraising the selected studies, it is not without limitations. As all of the studies reviewed were cross-sectional, the limitation of this type of study will be reflected. Some information was not reported in some of the studies. The recall periods used to assess the practice of self-medication varied across the studies, which made difficult to compare among prevalence rates. There was also high heterogeneity among the studies reviewed. This may have been due to a lack of standardized criteria for data-collection tools.

Conclusion

Self-medication practice is prevalent in Ethiopia and varied in different populations and regions of the country. Some of the self-medication practices are harmful and need prompt action. Implementation of laws that regulate drug dispensing should be emphasized. Special attention should be given to educating the public and health care providers on the type of illnesses that can be self-diagnosed and self-treated and the type of drugs to be used for self-medication.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The author reports no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Leyva-Flore R, Kageyama ML, Ervitin-Erice J. How people respond to illness in Mexico: self-care or medical care? Health Policy. 2001;57:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(00)00136-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abula T, Worku A. Self-medication in three towns of north west Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2001;15:25–30. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization The role of the pharmacist in self-care and self-medication. [Accessed October 26, 2016]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/whozip32e/whozip32e.pdf.

- 4.Sleath B, Rubin RH, Campbell W, Gwyther L, Clark T. Physician-patient communication about over-the-counter medications. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53:357–369. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Angamo MT, Wabe NT. Knowledge, attitude and practice of self-medication in southwest Ethiopia. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2012;3:1005–1010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eticha T, Mesfin K. Self-medication practices in Mekelle, Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang FR, Trivedi PK. Economics of self medication: theory and evidence. Health Econ. 2003;12:721–739. doi: 10.1002/hec.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization The benefits and risks of self-medication. WHO Drug Inf. 2000;14:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization The role of the pharmacist in the health care system. 1994. [Accessed February 8, 2017]. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/h2995e/h2995e.pdf.

- 10.Worku S, Mariam AG. Practice of self-medication in Jimma town. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2003;17:111–116. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gutema GB, Gadisa DA, Kidanemariam ZA, et al. Self-medication practices among health sciences students: the case of Mekelle University. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2011;1:183–189. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan RA. Self-Medication with Antibiotics: Practices among Pakistani Students in Sweden and Finland [master’s thesis] Huddinge (Sweden): Södertörns University; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mossa DA, Wabe NT, Angamo MT. Self-medication with antibiotics and antimalarials in the community of Silte Zone, south Ethiopia. Turk Silahlı Kuvvetleri Koruyucu Hekim Bul. 2012;11:529–536. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Almasdy D, Sharrif A. Self-medication practice with nonprescription medication among university students: a review of the literature. Arch Pharm Pract. 2011;2:95–100. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mihretie TM. Self-Medication Practices with Antibiotics among Urban Dwellers of Bahir Dar Town, North West Ethiopia [master’s thesis] Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes CM, McElnay JC, Fleming GF. Benefits and risks of self-medication. Drug Saf. 2001;24:1027–1037. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200124140-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruiz ME. Risks of self-medication practices. Curr Drug Saf. 2010;5:315–323. doi: 10.2174/157488610792245966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buck M. Self-medication by adolescents. J Pediatr Pharm. 2007;13:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pagane D. Self-medication and health insurance coverage in Mexico. Health Policy. 2007;75:170–177. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saleem TK, Sankar C, Dilip C, Azeem AK. Self-medication with over the counter drugs: a questionnaire based study. Pharm Lett. 2011;3:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature II: how to use an article about therapy or prevention. JAMA. 1994;271:59–63. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.1.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shehnaz SI, Agarwal AK, Khan N. A systematic review of self-medication practices among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2014;55:467–483. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bollu M, Vasanthi B, Chowdary PS, Chaitanya DS, Nirojini PS, Nadendla RR. Prevalence of self medication among the pharmacy students in Guntur: a questionnaire based study. World J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2014;3:810–826. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson D, Sekhar HS, Alex T, Kumaraswamy M, Chopra RS. Self-medication practice among medical, pharmacy and nursing students. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2016;8:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patil SB, Vardhamane SH, Patil BV, Santoshkumar J, Binjawadgi AS, Kanaki AR. Self-medication practice and perceptions among undergraduate medical students: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:20–23. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/10579.5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martins AP, Miranda AC, Mendes Z, Soares MA, Ferreira P, Nogueria A. Self-medication in a Portuguese urban population: a prevalence study. Pharmacoepidemial Drug Saf. 2002;11:409–414. doi: 10.1002/pds.711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hebeeb GE, Gearhart JG. Common patient symptoms: patterns of self-treatment and prevention. J Miss State Med Assoc. 1993;34:179–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sharma R, Verma U, Sharma CL, Kapoor B. Self-medication among urban population of Jammu city. Indian J Pharmacol. 2005;37:40–43. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Omolase CO, Adeleke OE, Afolabi AO, Afolabi OT. Self medication amongst general outpatients in a Nigerian community hospital. Ann Ib Postgrad Med. 2007;5:64–67. doi: 10.4314/aipm.v5i2.64032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shankar PR, Partha P, Shenoy N. Self-medication and non-prescription practices in Pokhara Valley, western Nepal: a questionnaire-based study. BMC Fam Pract. 2002;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaki IA. Self-medication practices among Malaysia undergraduate pharmacy students. 2010. [Accessed February 8, 2017]. Available from: http://malrep.uum.edu.my/rep/Record/uitm.ir.2218/Details.

- 32.Sawalha AF. Assessment of self-medication practice among university students in Palestine: therapeutic and toxicity implications. Islam Univ J. 2007;15:67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yousef AM, Al-Bakri AG, Bustanji Y, Wazaify M. Self-medication patterns in Amman, Jordan. Pharm World Sci. 2008;30:24–30. doi: 10.1007/s11096-007-9135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jasim AL, Fadhil TA, Taher SS. Self-medication practice among Iraqi patients in Baghdad city. Am J Pharmacol Sci. 2014;2:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flaiti MA, Badi KA, Hakami WO, Khan SA. Evaluation of self-medication practices in acute diseases among university students in Oman. J Acute Dis. 2014;3:249–252. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gaddam Damodar. Assessment of self-medication practices among medical, pharmacy and nursing students at a tertiary care teaching hospital. Indian J Hosp Pharm. 2012;49:79–83. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patil SB, Vardhamane SH, Patil BV, Jeevangi S, Ashok SB, Anand RK. Self-medication practice and perceptions among undergraduate medical students: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:20–23. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/10579.5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banerjee I, Bhadury T. Self-medication practice among undergraduate medical students in a tertiary care medical college, West Bengal. J Postgrad Med. 2012;58:127–131. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.97175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badiger S, Kundapur R, Jain A, et al. Self-medication patterns among medical students in South India. Australas Med J. 2012;5:217–220. doi: 10.4066/AMJ.2012.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ali SE, Ibrahim MI, Palaian S. Medication storage and self-medication behaviour amongst female students in Malaysia. Pharm Pract (Granada) 2010;8:226–232. doi: 10.4321/s1886-36552010000400004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharif SI, Ibrahim OH, Mouslli L, Waisi R. Evaluation of self-medication among pharmacy students. Am J Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;7:135–140. [Google Scholar]

- 42.James H, Handu SS, Al Khaja KA, Otoom S, Sequeira RP. Evaluation of the knowledge, attitude and practice of self-medication among first-year medical students. Med Princ Pract. 2006;15:270–275. doi: 10.1159/000092989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitka M. When teens self-treat headaches, OTC drug misuse is frequent result. JAMA. 2004;292:424–425. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.4.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Syed NZ, Reema S, Sana W, Akbar JZ, Talha V. Self medication amongst university students of Karachi: prevalence, knowledge and attitudes. J Pak Med Assoc. 2008;58:214–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khan RA. Self-medication with antibiotics: practices among Pakistani students in Sweden and Finland. 2011. [Accessed February 8, 2017]. Available from: http://sh.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A452461&dswid=-2995.

- 46.Awad AI, Eltayeb IB, Capps PA. Self-medication practices in Khartoum State, Sudan. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62:317–324. doi: 10.1007/s00228-006-0107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ocan M, Obuku EA, Bwanga F, et al. Household antimicrobial self-medication: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the burden, risk factors and outcomes in developing countries. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:742. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2109-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morgan DJ, Okeke IN, Laxminarayan R, Perencevich EN, Weisenberg S. Non-prescription antimicrobial use worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:692–701. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70054-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Radyowijati A, Haak H. Improving antibiotic use in low-income countries: an overview of evidence on determinants. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:733–744. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moraes AC, Delaporte TR, Molena-Fernandes CA, Falcão MC. Factors associated with medicine use and self-medication are different in adolescents. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2011;66:1149–1155. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322011000700005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Patel MM, Singh U, Sapre C, Salvi K, Shah A, Vasoya B. Self-medication practices among college students: a cross sectional study in Gujarat. Natl J Med Res. 2013;3:257–260. [Google Scholar]

- 52.da Silva C, Giugliani ER. Consumo de medicamentos em adolescentes escolares: uma preocupação. [Consumption of medicines among adolescent students: a concern] J Pediatr (Rio J) 2004;80:326–332. Portuguese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Du Y, Knopf H. Self-medication among children and adolescents in Germany: results of the National Health Survey for Children and Adolescents (KiGGS) Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68:599–608. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pereira FS, Bucaretchi F, Stephan C, Cordeiro R. Self-medication in children and adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2007;83:453–458. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Abahussain NA, Taha AZ. Knowledge and attitudes of female school students on medications in eastern Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:1723–1727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Young A. Medical and nonmedical use of prescription drugs among secondary school students. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40:76–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hansen EH, Holstein BE, Due P, Currie CE. International survey of self-reported medicine use among adolescents. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37:361–366. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Al-Azzam SI, Al-Husein BA, Alzoubi F, Masadeh MM, Al-Horani S. Self-medication with antibiotics in Jordanian population. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2007;20:373–380. doi: 10.2478/v10001-007-0038-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sanjana P, Barans MJ, Bangs MJ, et al. Survey of community knowledge, attitudes and practices during a malaria epidemic in central Java, Indonesia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:783–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stoelben S, Krappweis J, Rössler G, Kirch W. Adolescents’ drug use and drug knowledge. Eur J Pediatr. 2000;159:608–614. doi: 10.1007/s004310000503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Furu K, Skurtveit S, Rosvold EO. Selvrapportert legemiddelbruk hos 15–16-åringer i Norge. [Self-reported medical drug use among 15–16 year-old adolescents in Norway] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2005;125:2759–2761. Norwegian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chowdhury N, Matin F, Chowdhury SF. Medication taking behavior of students attending a private university in Bangladesh. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2009;21:361–370. doi: 10.1515/ijamh.2009.21.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alghanim SA. Self-medication practice among patients in a public health care system. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17:409–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Awad A, Eltayeb I, Matowe L, Thalib L. Self-medication with antibiotics and antimalarials in the community of Khartoum State, Sudan. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2005;8:326–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sapkota AR, Coker ME, Goldstein RE, et al. Self-medication with antibiotics for the treatment of menstrual symptoms in southwest Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:610. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Osemene KP, Lamikanra A. A study of the prevalence of self-medication practice among university students in southwestern Nigeria. Trop J Pharm Res. 2012;11:683–689. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shehnaz SI, Sreedharan J, Khan N, et al. Factors associated with self-medication among expatriate high school students: a cross-sectional survey in United Arab Emirates. Epidemiol Biostatist Public Health. 2013;10:e8724. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Befekadu A, Dekama NH, Mohammed AM. Self-medication and contributing factors among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Ethiopia: the case of Jimma University Specialized Hospital. Med Sci. 2014;3:969–981. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Abeje G, Admasie C, Wasie B. Factors associated with self-medication practice among pregnant mothers attending antenatal care at governmental health centers in Bahir Dar city administration, northwest Ethiopia, a cross sectional study. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;20:276. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2015.20.276.4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bekele SA, Argaw MD, Yalew AW. Magnitude and factors associated with self-medication practices among university students: the case of Arsi University, College of Health Science, Asella, Ethiopia: cross-sectional survey based study. Open Access Libr J. 2016;3:e2738. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Abay SM, Amelo W. Assessment of self-medication practices among medical, pharmacy, and health science students in Gondar University, Ethiopia. J Young Pharm. 2010;2:306–310. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.66798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hailemichael W, Sisay M, Mengistu G. Assessment of the knowledge, attitude, and practice of self-medication among Harar Health Sciences College students, Harar, eastern Ethiopia. J Drug Deliv Ther. 2016;6:31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tenaw A, Tsige GM. Self-medication practices in addis ababa: a prospective study. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2004;14(1):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ararsa A, Bekele A. Assessment of self-medication practice and drug storage on private pharmacy clients in Jimma town, Oromia, South west Ethiopia. AJPS. 2015;1(1):20–32. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jaleta A, Tesema S, Yimam B. Self-medication practice in Sire town, West Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Cukurova Med J. 2016;41(3):447–452. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abrha S, Molla F, Melkam W. Self-medication practice: the case of Kolladiba Town, North West Ethiopia. IJPSR. 2014;5(10):670–677. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Deressa W, Ali A, Enqusellassie F. Self-treatment of malaria in rural communities, Butajira, southern Ethiopia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2003;81:261–268. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sado E, Gedif T. Drug Utilization at Household Level in Nekemte Town and Surrounding Rural Areas, Western Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Open Access Library Journal. 2014;1:e651. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ali H. Self-medication practices in private pharmacies of Kolfe Keraneo Sub-city, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Harar Bulletin of Health Sciences. 2012;5:390–409. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Suleman S, Ketsela A, Mekonnen Z. Assessment of self-medication practices in Assendabo town, Jimma zone, southwestern Ethiopia. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2009;5:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gedif T. Self medication and its determinants in Butajira, southern Ethiopia. [master’s thesis] Addis Ababa: Addis Ababa University; 1995. [Google Scholar]