Abstract

Social relationships among adolescents with mental disorders are demanding. Adolescents with depressive symptoms may have few relationships and have difficulties sharing their problems. Internet may offer reliable and easy to use tool to collect real-time information from adolescents. The aim of this study is to explore how adolescents describe their social relationships with an electronic diary. Mixed methods were used to obtain a broad picture of adolescents’ social relationships with the data gathered from network maps and reflective texts written in an electronic diary. Adolescents who visited an outpatient clinic and used an intervention (N=70) designed for adolescents with signs of depression were invited to use the electronic diary; 29 did so. The quantitative data gathered in the electronic diary were summarized with descriptive statistics, and the qualitative data were categorized using a thematic analysis with an inductive approach. We found that social relationships among adolescents with signs of depression can vary greatly in regards to the number of existing relationships (from lacking to 21) and the quality of the relationships (from trustful to difficult). However, the relationships may change, and the adolescents are also willing to build up their social relationships. Professionals need to be aware of the diversity of adolescents’ social relationships and their need for personalized support.

Keywords: adolescent, depression, electronic diary, internet, social relationship

Introduction

Social relationships are understood to be connected to mental health. Relationships with friends1 and family environments affect the well-being of adolescents.2 The happiness of 12-year-old children can be predicted by the number of close friends,3 confidential family relationships,4 and the amount of emotional support they get from friends. It has also been found that peers crowd a sense of solidarity, and being in a dating relationship often protects adolescents against feelings of social anxiety.4 Out of 313 14 year old adolescents, 91% of boys and 84% of girls have described their relationships with their mothers to be warm, and 86% of boys and 69% of girls described their relations with their fathers to be warm.5 However, as adolescents transition from dependency to independency, challenges within families do arise.6 Social relationships are also important factors in regards to the general health of adolescents. Poor social relationships can affect their physical health, habits7 and adolescent development, and increase alcohol consumption, substance abuse, delinquent behaviors8 and mortality risk.7

Every fifth adolescent has some type of mental disorder9 which can lead to difficulties for those individuals, such as experiencing stigma in relationships with peers, family members and school staff.10 Adolescents with mental disorders have fewer school or community activities than their healthy peers.11 The School Health Promotion survey in Finland found that students lacking a close friend suffered from more anxiety disorders and loneliness, which was associated with problems in school.12 Adolescents with mental disorders have difficulties in their relationships and lack trusting relationships with people where they could share their honest feelings.13 Although adolescents with mental disorders may be withdrawn from social contacts, they still desire for people to take care of them and ensure their well-being.14 Therefore, family members, siblings and peers have an important role when adolescents are seeking help.15 They want to be understood by people close to them,14 they want to be part of a peer group and they want to be able to talk with someone about their problems.13 Family support in particular is important for young people, as strong support from parents has been associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms.16 The problem is, however, that adolescents with mental health problems have often difficulties in talking with adults about their problematic life situation.17,18

From 2006 to 2013 the outpatient visits in Finland due to depression increased by 104%.19 In 2013, in the age group of adolescents from 13 to 17 years of old, depression was the most common diagnosis made. At the same time, altogether 46,659 depression-related visits to adolescent outpatient clinics were made in Finland.19 Within the specialized field of adolescent psychiatry, outpatient care is preferred over inpatient care.20 According to the quality guidelines for adolescent psychiatric outpatient services, the assessment of adolescents should include a doctor’s examination (adolescent psychiatrist or resident), and elicit information about the family situation and other circumstances of the adolescent. If treatment begins, psychotherapy is an essential intervention with medication if needed and rehabilitation for improving ability to function.20

The internet is a potential tool for seeking support regarding mental health problems,21 especially for those with no one to discuss with.22 Internet interventions have already been designed for the prevention of depression, anxiety, stress, emotional distress and eating disorders.23 The internet may offer alternatives to conventional interventions in health care at lower costs24,25 and an anonymous way to share experience.24 It may also promote the care process by supporting adolescents’ self-management.26 One study in Australia showed that the internet is important to young men (N=486) who are willing to talk about their problems online (41%), although they still considered friends (87%), counselors (70%), doctors (67%) and their own family members (64%) as important sources of help.27

There is still a lack of studies in which adolescents describe their social relationships using internet tools. In the study of Henker et al, 155, 9th grade adolescents wrote in electronic diaries every 30 minutes for two 4-day intervals.28 Based on reported moods, activities, social settings, diet, smoking and alcohol use, they were further stratified into low-, middle- or high-anxiety groups. The authors found that high-anxiety teenagers also expressed higher levels of anger, sadness and fatigue, along with lower levels of happiness and well-being and also reported fewer conversations and tendency to spend less time with peers. Still, they were more likely to show reduced anxiety levels when in the company of friends. Other studies have used electronic diaries among adolescents with depression29 and have studied the relationship between stress and headaches.30 Using the internet as a data collection tool has also been acceptable for participants: it offers real-time information28,31 and it is easy to use.32

However, information is still missing on how usable electronic diaries are for describing social relationships among adolescents. By developing more user-friendly health care services for adolescents,33 we could offer new communication channels for those who may have difficulties with sharing their views with others.23 This study is linked to the Depis.Net study (ISRCTN80379583), a randomized controlled trial aiming to develop a user-friendly and feasible internet intervention for adolescents with depression. The internet intervention offers adolescents alternative ways to communicate and supports their coping skills, and is one response to adolescents’ needs for mental health treatment. The sample used for this article consists of adolescents participating in the intervention group. In addition to standard care, the adolescents in the intervention group accessed Depis.Net for 6 weeks. They had usernames and passwords, and used the intervention at home. The internet intervention consists of five themes, and included questionnaires, exercises and information. Finally, the adolescents were asked to provide feedback on using the internet intervention.34 In this study, we describe the results of the data where the adolescents have described their social relationships in electronic diary.

Materials and methods

Design

A mixed methods approach was used as a study design. In this study, we have combined quantitative and qualitative approaches to obtain a broad picture of adolescents’ social relationships35 and to ascertain the extent and quality of such relationships.7 The main focus was the perspectives of the adolescents themselves,35 keeping with patient-focused practices in this sensitive area of mental health.36 A combination of quantitative and qualitative approaches included a triangulation of the data. This means that the quantitative and the qualitative data collection and analysis were first conducted separately, and the results of both data sets were then merged.37 Thus, the quantitative data were analyzed by counting frequencies, and the qualitative data by means of a thematic analysis Braun and Clarke.38 The results were synthesized using matrices, and compared to identify the convergences of quantitative and qualitative data.35

Setting

The study was conducted in two Finnish hospital districts offering specialized health care services to a total of two million inhabitants in their areas.39 Within the time frame of 25 months, 1,371 adolescents were assessed for the study. Adolescents had been referred to psychiatric outpatient care with signs of depression or anxiety disorder, more detailed diagnoses were set during the treatment. Their number of visits in these two centers varied as adolescents visit there from one to weekly appointments with their therapists.

Study participants

The data were collected from adolescents referred to adolescent psychiatric outpatient clinics for showing symptoms of depression or anxiety. These adolescents were randomized to an intervention group and were introduced to the Depis.Net internet intervention. The participants were Finnish-speaking adolescents from 15 to 17 years old. Patients with severe mental disorders (eg, psychotic depression, bipolar disorder, substance abuse or primary eating disorder) were excluded, as the content of our support system (eg, psychoeducation) focuses on depression or anxiety disorders. Based on earlier studies, web-based support systems are effective for mild and moderate depression about what the related literacy is described in the development paper of the Depis.Net support system.34 Moreover, excluded were those adolescents who were admitted to psychiatric hospital wards during the course of the intervention.

At the outpatient clinics, 1,371 adolescents were assessed for eligibility. Adolescents had been referred to psychiatric outpatient care with signs of depression or anxiety disorder, more detailed diagnoses were set during the treatment. Some adolescents were referred to the clinics, for example, by their school nurse. Out of them, 537 were randomized and 423 met the inclusion criteria. Out of adolescents who were eligible and willing to participate, 158 were allocated in two study groups (intervention and control group). The 75 adolescents included in the intervention group and instructed to participate in the Depis.Net internet intervention, five withdrew before the intervention started and 70 used it. Out of these, 29 adolescents (28 females and 1 male) described their social relationships. These 29 adolescents produced the data used in this sub-study.

Method for data collection

Participant characteristic data such as gender, age, education and previous use of mental health care services was collected from the adolescents’ patient records by the nurses at the outpatient clinics. Background information about adolescent families were not collected.

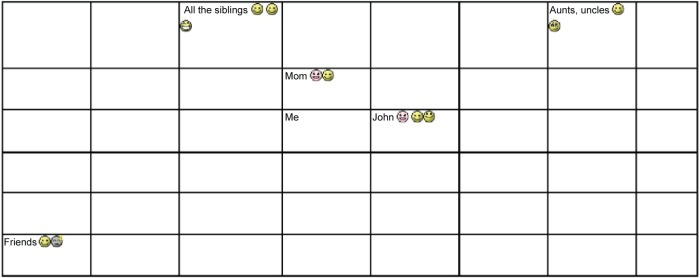

Data were collected from 2008 to 2010 through an electronic diary, which was a part of the Depis.Net website. Adolescents were first instructed to describe their social relationships by creating a visual network map,40 identifying people close to them on the map and plotting them with a smiley face symbol. Time frame for adolescent social relationships was not specified. The visual form for the descriptions was selected because adolescents have often problems with formulating their feelings and perceptions. Also, smileys are already used in many mobile solutions (Figure 1). Second, the adolescents were asked to reflect on these social relationships in written format: 1) what they were satisfied with and 2) what would they like to change in their social relationships.

Figure 1.

An example of an adolescent’s network map.

Data analysis

The data in the electronic diary were printed out to explore the adolescents’ network maps in visual format and reflective texts (a total of 6 pages, 1.5 line spacing). Two authors (MA, KA) were responsible for the data analysis. The quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed separately, but integration and a matrix were used together to combine and summarize the results.37 The analyses of both the quantitative and qualitative data are described in the following section.

Quantitative analysis

A number of plotted relationships were first identified on the network map, such as family, mother, father, sibling, relative, friend, girlfriend or boyfriend, people by name and pets. Grandparents and cousins were counted as relatives, and schoolmates as friends. Frequencies (and mean values) were calculated. All figures were transferred in numerical form to the SPSS data matrix as follows: if the adolescent’s mother was marked on the network map, it was counted as yes =1, and if she was not marked it was counted as no =0. Descriptive statistics were applied with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) statistics 22 software.41

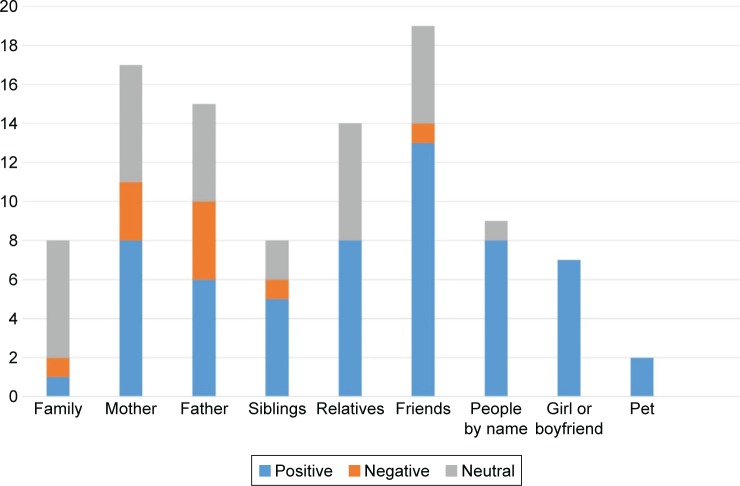

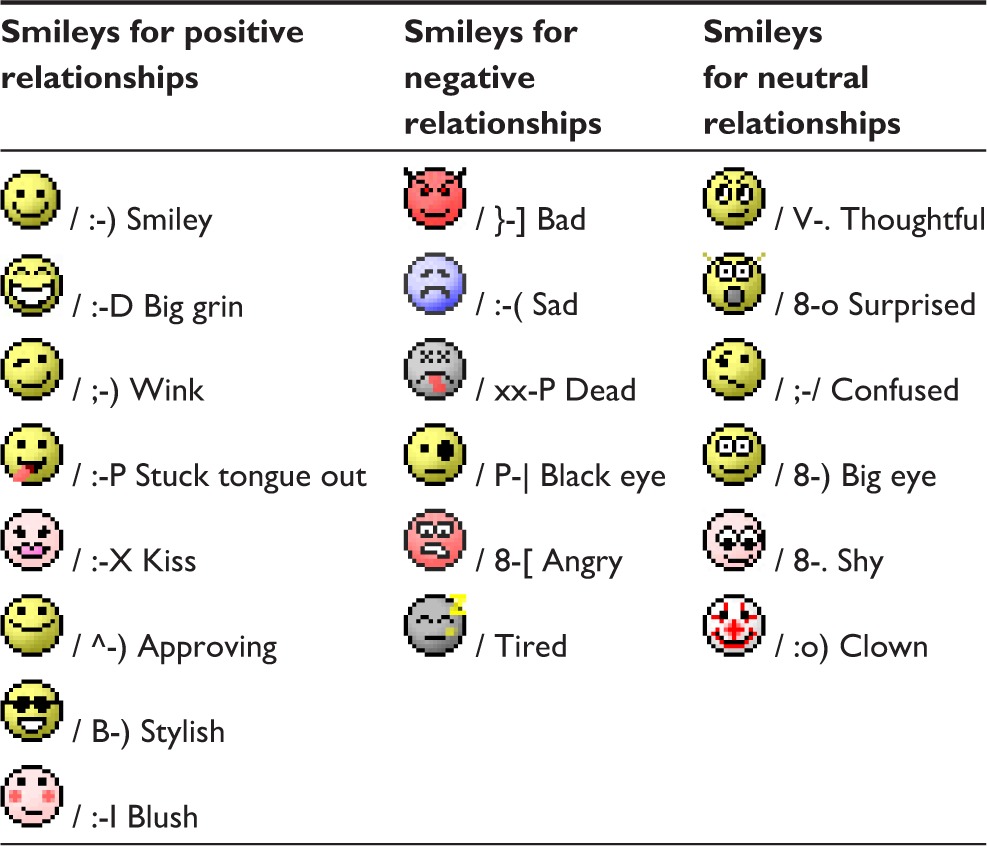

Second, the quality of social relationships, reflected by smileys and used by adolescents a lot, was analyzed by categorizing the smileys into specified themes based on the connotation attached to the smileys. They were issued the following values: positive (code 2), neutral relationship/not identified in the network map (code 1) and negative relationship (code 0). The data were coded and values were transferred to SPSS. If more than one smiley expressed the quality of each relationship, a mean value was counted. For example, if the quality of a social relationship with a friend was visualized with three smileys: a smiling smiley (+, code 2), a winking smiley (+, code 2) and bad (−, code 0), that relationship was scored as positive. The meanings of the smileys and how to divide the smileys into themes were verified by young people from three different countries. The smileys used are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Smileys used by adolescents to visualize the quality of their social relationships

|

Qualitative analysis

The adolescents’ reflective writings were analyzed with a thematic analysis38 using an inductive approach.42 The specific phases of thematic analysis were conducted according to Braun and Clarke38 to create a systematic but flexible analysis process. We first read the printed material several times. Second, the preliminary codes were formed and manually highlighted in the text. Third, the data were categorized into two main themes: the extent of the social relationships among adolescents and the quality of social relationships. The preliminary themes were formed based on the data, and the heterogeneity and homogeneity of the themes were reviewed and further modified. Fourth, the themes were formed in three levels: general themes, sub-themes and codes. Fifth, the themes and sub-themes were named to bring out the core of each adolescent’s initial message. Finally, the results were written to provide a logical and extensive description with sufficient data extracts and to answer the research question.38

Reliability and validity of the analysis

Related to the qualitative analysis, one co-author (MV) reanalyzed the themes to ensure the credibility of the analysis.36 We also verified the meanings of the smileys by asking conveniently 31 young people (15 males and 16 females) from three different countries (Finland, USA, and Estonia) about how to divide the smileys into themes. It provided us international verification into the classification of the themes. These young people were from the main population and as far we know, they were not in the circumstances of mental health care services. Their sociodemographic information was neither collected, nor did we collect information about their mental state or depressive symptoms. The agreement percentage was calculated and the nature of a smiley was agreed upon if two out of three (67%) people perceived it the same way (positive, negative or neutral). Five smileys (blush, tired, big eyes, clown and shy) remained unclear. Based on the verification, we divided these unclear topics according to how the majority of adolescents divided them into themes.

Ethical issues

Ethical approval (R08075H) was granted by The Ethics Committee of the Pirkanmaa Hospital District, and study permission was obtained from the hospital administrators of the hospital districts. The ethical guidelines in social and health care were followed respecting the interests of the adolescents.43 The practices throughout the study process likewise adhered to good scientific practice,44 the principles for medical research and the appropriate legislation.45 The process of the study was explained to the adolescents verbally and in writing. Written informed consent was required from the adolescents before participation, and withdrawal was allowed at any time without needing to give any reason. The parents were informed about the study; however, the consent was not required from them since the adolescents were 15 years old. The well-being of the adolescents was ensured by monitoring the internet intervention. In such cases where there was a serious threat to a participant’s well-being, for example, a threat of suicide, a tutor was obligated to contact the health care staff in charge of adolescent care. The data were also handled confidentially and anonymity was ensured in the internet intervention by using unidentifiable ID codes as usernames, even though the adolescents could not see each other’s exercises. Anonymity was respected when reporting the results.

Results

Participant characteristics

Out of study participants describing social relationships (n=29; 41.4%), almost all were females (n=28; 96.7%). Almost half of them were in high school (n=14; 48.3%). The mean age of the participants were 15.9 years and more than half of them (n=18; 62.1%) had previously used mental health care services. Out of those who did not describe their social relationships (n=41; 58.6%), the number of males were one-third (n=14; 34.1%) and those who were in high school (n=15; 36.6%). Their mean age was 16.1 years and majority of them (n=33; 80.5%) had previously used mental health care services (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the participants describing and nondescribing social relationships

| Characteristics | Participants (n=29, 41.4%), n (%) |

Nonparticipants (n=41, 58.6%), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 28 (96.6) | 27 (65.9) |

| Male | 1 (3.4) | 14 (34.1) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 15 | 12 (41.4) | 10 (24.4) |

| 16 | 7 (24.1) | 18 (43.9) |

| 17 | 10 (34.5) | 13 (31.7) |

| Education | ||

| In comprehensive school | 10 (34.5) | 13 (31.7) |

| Completed comprehensive school | 2 (6.9) | 6 (14.6) |

| In high school | 14 (48.3) | 15 (36.6) |

| In vocational school | 3 (10.3) | 5 (12.2) |

| Other/not known | 0 (0) | 2 (4.9) |

| Previous use of mental health care services | ||

| Yes | 18 (62.1) | 33 (80.5) |

| No | 9 (31.0) | 17 (17.1) |

| Not known | 2 (6.9) | 1 (2.4) |

Extent and identification of the adolescents’ relationships

The adolescents reported the extent of their social relationships (collected in Table 3) and plotted the people in their lives on the network map (example in Figure 1). These maps showed that the number of social relationships per adolescent ranged from 2 to 21, but the reflective texts of some participants also mentioned a lack of relationships. On average, each adolescent identified eight social relationships (mean =8.3).

Table 3.

Matrix of extent and identification of the adolescents’ social relationships based on quantitative and qualitative data (n=29)

| Extent and identification of social relationships based on network maps n (%) | Extent and identification of social relationships based on written text n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Family | |||

| Mother | 18 (62.1) | Mother | 7 (24.1) |

| Father | 15 (51.7) | Family | 7 (24.1) |

| Family | 8 (27.6) | Father | 4 (13.8) |

| Sibling | 8 (27.6) | Sibling | 4 (13.8) |

| Stepfather | 1 (3.5) | Stepfather | 1 (3.5) |

| Stepmother | 1 (3.5) | ||

| Relatives | |||

| Relatives | 7 (20.7) | Grandparent | 2 (6.9) |

| Grandparent | 5 (17.2) | Relatives | 1 (3.5) |

| Uncle/aunt | 1 (3.5) | Uncle/aunt | 1 (3.5) |

| Cousin | 1 (3.5) | ||

| Peers | |||

| Friend | 19 (65.5) | Friends | 10 (34.5) |

| Boyfriend or girlfriend | 7 (24.1) | Boyfriend of girlfriend | 5 (17.2) |

| Other social relationships | |||

| People by name | 9 (31.0) | People by name | 5 (17.2) |

| Godparent | 3 (10.3) | Godparent | 1 (3.5) |

| Pet | 2 (6.9) | Pet | 1 (3.5) |

| Lack of social relationships | |||

| Lack of social relationships | 5 (17.2) | ||

To describe their social relationships, five sub-themes were created: peers, family, relatives, other social relationships and lack of relationships. First, the adolescents most often plotted relationships with their friends (n=19). They described having numerous good friendships or that they had few but enough friends. Boyfriends and girlfriends were also mentioned and plotted on the network map (n=7). Second, family was described as a constant part of their lives. They plotted mothers the most (n=18), followed by fathers (n=15), siblings (n=8) and family, in general (n=8) on their network maps. Third, the adolescents acknowledged relatives (n=7), such as grandparents (n=5), uncles and aunts (n=1) in their lives. Fourth, names of people were provided to represent other social relationships without any specific information about who they were (n=9). The roles of godparents (n=3) and pets (n=2) were also emphasized. Fifth, the adolescents wrote about lacking people, or having lost connections with people, in their lives. In Table 3, the extent and identification of social relationships are collected based on quantitative and qualitative data.

The quality of relationships

The quality of the adolescents’ relationships was categorized as positive, negative or neutral.

Positive relationships

Positive social relationships were described by one sub-theme: trusting relationships. The adolescents reported having trusting relationships with family members, friends or grandparents (n=13), using smileys on the network maps (Figure 2). The concrete help and understanding obtained from these people made the adolescents feel satisfied. Some appreciated a mother who would pick them up and bring them home in the middle of the night or let them know they could always turn to her if needed. In regards to peers, real support and understanding in difficult times were important. If a friend had a similar difficult experience, it increased the understanding between adolescents.

Figure 2.

Quality of adolescents’ social relationships according to smileys.

Dating was also part of the adolescents’ lives, and all those who marked a girlfriend or a boyfriend on their network maps reported those relationships to be positive (n=7), as being the closest and the most beloved people in their lives. One adolescent wrote about feelings regarding a close relationship: “I’m happy that I have always had close relationships with my family” (ID 475).

Negative relationships

Negative social relationships were described by two sub-themes: distant relationships and difficult relationships. First, in regards to distant relationships, adolescents omitted family from the network map because family seemed unimportant. Quantitatively, negative relationships were identified with a mother (n=3), father (n=4) and siblings (n=1; Figure 2). The adolescents felt they were outsiders or had no warm relationships within the family. Some wrote that they had no close people in their lives or that people were alienated from them. Friendships were superficial, without the feeling of needing somebody. Physical distance or studying at different schools also hindered interaction with friends. One adolescent reflected:

There is no desire to go anywhere, even with X (a year ago we were almost constantly together), it is an option that does not even occur to me (ID 7).

Second, the adolescents reported difficult social relationships. They lacked understanding from others, or they were disappointed and dissatisfied in their social relationships. They felt anger, anxiety, jealousy and friction toward family members, and that caused conflicts in their lives. The adolescents also felt anxiety when agonizing over friends’ problems, such as suicidal thoughts or depressed moods. The adolescents were unsure about their sociability and struggled with poor self-confidence and the fear of losing a partner.

Maybe I am just extremely shy. Maybe I am just stupid. But all the time our relationship (with a best friend) is getting worse, and I don’t dare to do anything about it (ID 225).

Neutral relationships

Some of the adolescents’ social relationships were described as neutral, that is, with family (n=6), mothers (n=6) and fathers (n=5). Neutral relationships were described by two sub-themes: ordinary relationships and the development of relationships. First, the adolescents wrote about ordinary social relationships with people. Some adolescents thought that their relationships with their parents would be better if they were no longer living in their childhood home. Relatives were described as nice if met rarely enough, and adolescents (n=6) considered their relationships with relatives to be neutral. The adolescents reflected that it is normal at this age to have better relationships with friends or partners than with parents or relatives. The adolescents reported having good and bad periods with friends. They also reported that if friends were similar to themselves they managed better together. “With best friends everything is OK, at least as OK as it can be for somebody like me” (ID 225).

Second, the adolescents described the development of social relationships. Their social relationships were not static, that is, negative relationships could become more positive with time. They described that the balance wavered because either they or the people around them changed. They desired to build up relationships and also to learn new coping skills for difficult situations. If their relationships with their parents were distant, they wanted to be closer with them. The adolescents wanted to have more friends or to be bolder in relationships with peers. They wanted to take care of their relationships even if it was not always easy. “I would like to be a better friend, sister, child and girlfriend” (ID 475). Table 4 presents the matrix of the quality of the adolescents’ social relationships according to the quantitative and qualitative data.

Table 4.

Matrix of the quality of the adolescents’ social relationships as seen in the quantitative and qualitative data

| Quality of social relationships based on 99 smileys on network maps | Quality of social relationships based on written texts |

|---|---|

| Positive relationships | Positive relationships |

| 59% of all relationships | Trusting relationships |

| Negative relationships | Negative relationships |

| 10% of relationships | Distant relationships Difficult relationships |

| Neutral relationships | Neutral relationships |

| 31% of relationships | Ordinary relationships Development of relationships |

Discussion

In this study, we have explored how adolescents describe their social relationships using an electronic diary. The adolescents brought out the great diversity of the social relationships from those lacking to those having several (as many as 21 social relationships) and from difficult relationships to trustful. Based on the network maps, adolescents’ usually had around eight social relationships in their life. In this study, the adolescents also estimated the quality of their social relationships, suggested that relationships could develop and change over time, and they were actively willing to build up their relationships.

The topic is appropriate, because many online and mobile applications have been developed for mental health care services, but less often for the visualization of adolescents’ descriptions of their social relations. For mental health professionals, being aware of young people’s social relationships is important, because social relationships are associated with well-being,1,2 happiness3 and health.7 It has been found that the risk of depression is significantly greater among those with social strain, a lack of social support and poor overall quality of relationships.46 They also found that those with the lowest overall quality of social relationships had more than double the risk of depression, compared to those with the highest quality. Therefore, for preventive purposes, it is extremely important that mental health professionals can identify, as early as possible, any problems that occur in adolescents’ social network. Previously it has already shown that high-anxiety teenagers are more likely to show reduced anxiety when in the company of friends.28 Therefore, all recovery and preventive interventions supporting adolescents’ abilities and skills for developing and maintaining social relationships should be supported.

The meaning of peer support in an adolescent’s life is not always fully understood in the context of prevention or recovery from mental health problems.8 It has previously been found that belonging to a peer group and having trusted people in their lives are very important elements in an adolescent’s daily context.13 Other people are important for preventing the occurrence of and fostering recovery from mental health problems, and can have an effect on the adolescent’s attempts to seek help.15 It is, therefore, important for various professionals who work with adolescents to identify whether or not the adolescents have supportive people around them, and if not, be capable of supporting them to establish contacts with others, so to promote their recovery and overall well-being.

Any type of intervention that would improve relationships in the lives of adolescents would be valuable. The extent and the quality of social relationships among young people should be taken seriously, especially those who are in danger of any type of mental discomfort or have difficulties with conceptualizing thoughts and feelings when communicating with adults. The data used in this study were gathered via an electronic diary. In this small-scale sub-study, we have shown that there is great diversity in the amount and types of social relationships that adolescents have; some lack any friends, and others have a number of relationships, some have difficult relationships, while others have good and trustful friendships. As it is previously described, electronic diaries can sharpen differentiations between people with anxiety compared to questionnaire scores.28 Therefore, it is important to find ways to combine an analysis of social friendships with quantitative and qualitative approaches.

The adolescents showed that they could reflect on their social relationships by working independently online. This has also been demonstrated in previous studies.47–49 Internet intervention might, therefore, have something more to offer in mental health care services for adolescents. This is in line with research21,23 on offering flexible and easy-access mental health care services23 and information for confidential health issues.21,22 Electronic diaries have been found to be acceptable and easy to use46 even though adolescents might complete paper-and-pencil modes more and find them less bothersome to use.49 In our study, only 29 out of 70 young people (41%) took this opportunity to use an electronic diary. The females were greatly overrepresented among those who described social relationships in this study (96.6%) versus males not describing their social relationships (34.1%). This supports the idea that electronic devices may not be suitable for everyone, and it might be more suitable for girls. Therefore, more studies are needed to identify the effects of electronic diaries on the mental well-being for adolescents.

Limitations

This study has a few limitations. First, due to using the type of data with limited descriptions of adolescents’ personal lives, the analyses may include some incorrect interpretations of the social relationships identified. Due to privacy issues, however, the researchers did not confirm with the participants that the interpretations were correct. Second, the quality of social relationships was illustrated using smileys ranging from positive, through neutral to negative. Momentary feelings may have affected the adolescents’ decisions when choosing the smileys and describing their social relationships. Third, females were overrepresented in this sample. We do not know if males have similar friendships in their social relationships. However, in this sample, that is, adolescents with signs of depression, girls represented a typical group, that is, 79% of adolescents with depression aged 13–17 were girls.19 Fourth, 41% out of 70 adolescents participated in the study. The rate is bigger than average dropout rate (31%) from internet-based treatment.50 However, there is still lacking information about the reasons why some adolescents are not willing to use these kind of support systems. Despite these limitations, this study offers a new perspective on collecting data on social relationships among adolescents with signs of depression and understanding them more deeply in the daily lives of people in this age group.

Conclusion

This study showed that adolescents with mental challenges vary in terms of the amount and nature of the social relationships they maintain, which should be taken into account in preventing and treating their mental health. Electronic diaries might be a useful tool in identifying hidden problems as well as problems that are difficult to identify in oral communication. The results of this small-scale sub-study can be used to develop flexible mental health care and new ways for adolescents to express themselves, as well as to facilitate the sharing of feelings of adolescents with psychiatric symptoms. However, more studies with larger sample sizes are needed to ensure that the study results and interpretations are valid.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the grants of Professor Maritta Välimäki: the Academy of Finland under Grant (8214245), the Hospital District of Southwest Finland under Grant (13893), The Paulo Foundation, the Finnish Cultural Foundation, the Yrjö Jahnsson Foundation under Grant (5920), Professor Pool and the University of Turku.

Footnotes

Author contributions

KA contributed to the design of the study, data analysis and writing the manuscript. MA contributed to the conception of the study, design of the study, data collection, data analysis, and writing the manuscript. MK contributed to the data collection and writing the manuscript. MV contributed to planning and organizing the Depis.Net RCT study, the conception of the study, writing the manuscript and supervised the study.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Almquist YB, Östberg V, Rostila M, Edling C, Rydgren J. Friendship network characteristics and psychological well-being in late adolescence: exploring differences by gender and gender composition. Scand J Public Healt. 2014;42(2):146–154. doi: 10.1177/1403494813510793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Phillips TM. The influence of family structure vs. family climate on adolescent well being. Child Adolesc Social Work J. 2012;29(2):103–110. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uusitalo-Malmivaara L, Lehto JE. Social factors explaining children’s subjective happiness and depressive symptoms. Soc Indic Res. 2013;111(2):603–615. [Google Scholar]

- 4.La Greca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: do they predict social anxiety and depression? J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34(1):49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinnunen P. Nuoruudesta kohti aikuisuutta. Varhaisaikuisen mielenterveys ja siihen yhteydessä olevat ennakoivat tekijät [From Adolescence Towards Adulthood. Mental Health in Early Adulthood and Connecting and Proactive Facts] [dissertation] Finland: University of Tampere, Acta Universitatis Tamperensis; 2011. p. 1676. Finnish. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aalberg V, Siimes MA. Lapsesta Aikuiseksi, Nuoren Kypsyminen Mieheksi Tai Naiseksi [From child to adult, development of adolescent to man or woman] Helsinki: Kustannus oy Nemo. 2007:125–130. Finnish. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(Suppl):S54–S66. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization Adolescents and Mental Health. 2016. [Accessed February 10, 2017]. [updated July 29, 2016; cited February 3, 2016]. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/topics/adolescence/mental_health/en/

- 9.Costello EJ, Copeland W, Angold A. Trends in psychopathology across the adolescent years: what changes when children become adolescents, and when adolescents become adults? J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(10):1015–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moses T. Being treated differently: stigma experiences with family, peers, and school staff among adolescents with mental health disorders. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(7):985–993. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burnett-Zeigler I, Walton MA, Ilgen M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of mental health problems and treatment among adolescents seen in primary care. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(6):559–564. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute of Health and Welfare Kouluterveyskysely: Ystävyyssuhteet tukevat nuorten hyvinvointia [The School health promotion study: friendships support adolescents’ well-being] [Accessed February 10, 2017]. [updated September 21, 2015; cited February 3, 2016]. Available from: https://www.thl.fi/fi/-/kouluterveyskysely-ystavyyssuhteet-tukevat-nuorten-hyvinvointia. Finnish.

- 13.Anttila K, Anttila M, Kurki M, Hätönen H, Marttunen M, Välimäki M. Concerns and hopes among adolescents attending adolescent psychiatric outpatient clinics. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2015;20(2):81–88. doi: 10.1111/camh.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woodgate RL. Living in the shadow of fear: adolescents’ lived experience of depression. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56(3):261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wisdom JP, Agnor C. Family heritage and depression guides: family and peer views influence adolescent attitudes about depression. J Adolesc. 2007;30(2):333–346. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meadows SO, Brown JS, Elder Jr GH. Depressive symptoms, stress, and support: gendered trajectories from adolescence to young adulthood. J Youth Adolesc. 2006;35(1):93–103. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Branje SJ, Hale WW, Frijns T, Meeus WH. Longitudinal associations between perceived parent-child relationship quality and depressive symptoms in adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38(6):751–763. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9401-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marttunen M, Karlsson L. Marttunen M, Huurre T, Sandström T, Viialainen R, editors. Masennusoireilu ja masennustilat [Depressive symptoms and depression] Nuorten mielenterveyshäiriöt. Opas nuorten parissa työskenteleville aikuisille [Adolescents’ Mental Disorders. Guide for Adults Work with Adolescents] 2013. [Accessed February 10, 2017]. pp. 41–58. [cited February 3, 2016]. Available from: https://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/110484/THL_OPA025_2013.pdf?sequence=1. Finnish.

- 19.Rainio J, Räty T. Psychiatric specialist medical care 2013. Statistical report. National Institute for Health and Welfare; [Accessed February 10, 2017]. issn: 1798-0887. [cited March 5, 2016]. Available from: http://www.julkari.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/125570/Tr02_15_fi_sv_en.pdf?sequence=8. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pylkkänen K. Nuorisopsykiatrisen avohoidon laatusuositus [Quality of psychiatric outpatient services for adolescents in Finland] [cited February 3, 2016]. Quality indicators, measures, standards and outcomes. Report of the NALLE-project. Helsinki, Finland: Finnish Association of adolescent psychiatry; 2013. [Accessed February 10, 2017]. Available from: http://www.nuorisopsykiatrinen-yhdistys.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/SNPY_laatusuositus_1013.pdf. Finnish. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horgan A, Sweeney J. Young students’ use of the internet for mental health information and support. J Psychiatr Ment Health. 2010;17(2):117–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitchell KJ, Ybarra ML, Korchmaros JD, Kosciw JG. Accessing sexual health information online: use, motivations and consequences for youth with different sexual orientations. Health Educ Res. 2014;29(1):147–157. doi: 10.1093/her/cyt071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slone NC, Reese RJ, McClellan MJ. Telepsychology outcome research with children and adolescents: a review of the literature. Psychol Serv. 2012;9(3):271–292. doi: 10.1037/a0027607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andersen AJW, Svensson T. Internet-based mental health services in Norway and Sweden: characteristics and consequences. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2013;40(2):145–153. doi: 10.1007/s10488-011-0388-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barak A, Grohol JM. Current and future trends in internet-supported mental health interventions. J Technol Hum Serv. 2011;29(3):155–196. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurki M, Koivunen M, Anttila M, Hätönen H, Välimäki M. Usefulness of internet in adolescent mental health outpatient care. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(3):265–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01661.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ellis LA, Collin P, Hurley PJ, Davenport TA, Burns JM, Hickie IB. Young men’s attitudes and behaviour in relation to mental health and technology: implications for the development of online mental health services. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-13-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Henker B, Whalen CK, Jammer LD, Delfino RJ. Anxiety, affect, and activity in teenagers: monitoring daily life with electronic diaries. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(6):660–670. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoek W, Schuurmans J, Koot H, Cuijpers P. Effects of Internet-based guided self-help problem-solving therapy for adolescents with depression and anxiety: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43485. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Björling EA. The momentary relationship between stress and headaches in adolescent girls. Headache. 2009;49(8):1186–1197. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellis-Davies K, Sakkalou E, Fowler NC, Hilbrink EE, Gattis M. CUE: the continuous unified electronic diary method. Behav Res Methods. 2012;44(4):1063–1078. doi: 10.3758/s13428-012-0205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lam J, Barr RG, Catherine N, et al. Electronic and paper diary recording of infant and caregiver behaviors. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(9):685–693. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181e416ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization Making Health Services Adolescent Friendly: Developing National Quality Standards for Adolescent Friendly Health Services. [Accessed February 10, 2017]. [cited February 3, 2016]. Available from: http://www.who.int/maternal_child_adolescent/documents/adolescent_friendly_services/en/

- 34.Välimäki M, Kurki M, Hätönen H, et al. Developing an internet-based support system for adolescents with depression. JMIR Res Protoc. 2012;1(2):e22. doi: 10.2196/resprot.2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kettles AM, Creswell JW, Zhang W. Mixed methods research in mental health nursing. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18(6):535–542. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas E, Magilvy JK. Qualitative rigor or research validity in qualitative research. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2011;16(2):151–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2011.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark VLP, Huddleston-Casas CA, Churchill SL, Green DO, Garrett AL. Mixed methods approaches in family science research. J Fam Issues. 2008;29(11):1543–1566. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Municipaties.net Sairaanhoitopiirien ja erityisvastuualueiden (erva) asukasluvut [Population in hospital districts and catchment areas for highly specialized medical care] [Accessed February 10, 2017]. [Updated August 12, 2016; cited October 25, 2016]. Available from: http://www.kunnat.net/fi/kunnat/sairaanhoitopiirit/asukasluvut/Sivut/default.aspx. Finnish.

- 40.Hintermair M. The social network map as an instrument for identifying social relations in deaf research and practice. Am Ann Deaf. 2009;154(3):300–310. doi: 10.1353/aad.0.0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.IBM Software SPSS Statistics. [Accessed February 10, 2017]. [cited October 28, 2015]. Available from: https://www-01.ibm.com/software/fi/analytics/spss/products/statistics/products.html. Finnish.

- 42.Hsieh H, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Advisory Board on Health Care Ethic . Sosiaali ja terveysalan eettinen perusta [Ethical bases of social and health care] National Advisory Board on Health Care Ethics, Ministery of Social and Health; [Accessed February 10, 2017]. [cited February 3, 2016] Available from: http://etene.fi/documents/1429646/1559058/ETENE-julkaisuja+32+Sosiaali-+ja+terveysalan+eettinen+perusta.pdf/13c517e8-6644-4fa5-8c5f-193cfdce9841. Finnish. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Finnish Advisory Board on Research Integrity, TENK Hyvä tieteellinen käytäntö ja sen loukkausepäilyjen käsitteleminen Suomessa [Good scientific practice and proceeding with violations in Finland] [Accessed February 10, 2017]. Available from: http://www.tenk.fi/sites/tenk.fi/files/HTK_ohje_2012.pdf. Finnish.

- 45.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191–2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Teo AR, Choi H, Valenstein M. Social relationships and depression: ten-year follow-up from a nationally representative study. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62396. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Irealand AM, Wiklund I, Hsieh R, Dale P, O’Rourke E. An electronic diary is shown to be more reliable than a paper diary: results from a randomized crossover study in patients with persistent asthma. J Asthma. 2012;49(9):952–960. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2012.724754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krogh AB, Larsson B, Salvesen Ø, Linde M. A comparison between prospective Internet-based and paper diary recordings of headache among adolescents in the general population. Cephalalgia. 2016;36(4):335–345. doi: 10.1177/0333102415591506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palermo T, Valenzuela D, Stork PP. A randomized trial of electronic versus paper pain diaries in children: impact on compliance, accuracy, and acceptability. Pain. 2004;25(4):299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Melville KM, Casey LM, Kavanagh DJ. Dropout from internet-based treatment for psychological disorders. Br J Clin Psychol. 2010;49(Pt 4):455–471. doi: 10.1348/014466509X472138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]