Abstract

The American Society of Clinical Oncology released its first Guidance Statement on Cost of Cancer Care in August 2009, affirming patient-physician cost communication was a critical component of high-quality care. This forward-thinking recommendation has grown increasingly important in oncology practice today as the high costs of cancer care impose tremendous financial burden to patients, their families, and the healthcare system. In this review article, we conducted a literature search using Pubmed and Web of Science to identify articles covering three topics related to patient-physician cost communication: patient attitude, physician acceptance, and the associated outcomes. We identified fifteen papers from twelve distinct studies. While the majority of articles we reviewed on patient attitude suggested cost communication is desired by more than half of patients in the respective study cohorts, less than one-third of patients in these studies had actually discussed costs with their physicians. The literature on physician acceptance indicated that while 75% of physicians considered discussing out-of-pocket costs with patients their responsibility, less than 30% felt comfortable with such communication. When asked about whether cost communication actually took place in their practice, percentages reported by physicians varied widely, ranging from < 10% to > 60%. The data suggested that cost communication was associated with improved patient satisfaction, lower out-of-pocket expenses and a higher likelihood of medication non-adherence; none of these studies established causality. Both patients and physicians expressed a strong need for accurate, accessible, and transparent cost information.

INTRODUCTION

Therapeutic advances in oncology have improved survival of cancer patients. However, clinical improvements achieved by new oncologic treatments often come with a high price tag. Numerous researchers have cautioned the high costs of cancer drugs when targeted therapy agents first became available in the United States, noticing that agents such as trastuzumab could increase the cost of chemotherapy by $50,000 for breast cancer patients1 and the combination of irinotecan and cetuximab would push the cost of a full course of chemotherapy to $160,000 for colorectal cancer patients.2 As the price of cancer drugs continue to rise, the financial burden of cancer care grows increasingly worrisome.3, 4 Driven by the concern that rising costs can threaten the affordability of high-quality cancer care, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) established a Cost of Care Task Force in 2007. This task force published a Guidance Statement on the Cost of Cancer Care in 2009, marking one of the first official efforts from a specialty society to affirm patient-physician cost communication as a key component of high-quality care.5 The importance of cost communication was also emphasized in the 2013 Institute of Medicine report on cancer care quality.6

While ASCO's Cost of Cancer Care Guidance Statement is well-reasoned, concerns have been voiced that patients may feel uncomfortable discussing costs of their treatment options with physicians.7 Similar concerns were shared among physicians who felt ill prepared to undertake a dialogue involving costs.8, 9 To achieve cost transparency through patient-physician cost communication, it is necessary that the key stakeholders (patients, their families, and healthcare providers) are willing to engage in this conversation. In this article, we performed a comprehensive literature review of articles published after the release of the Guidance Statement from ASCO's Cost of Care Taskforce to better understand the attitudes toward and actual conduct of cost communication among cancer patients and oncologists. We also identified studies that assessed the association between cost communication and various outcomes measures.

METHODS

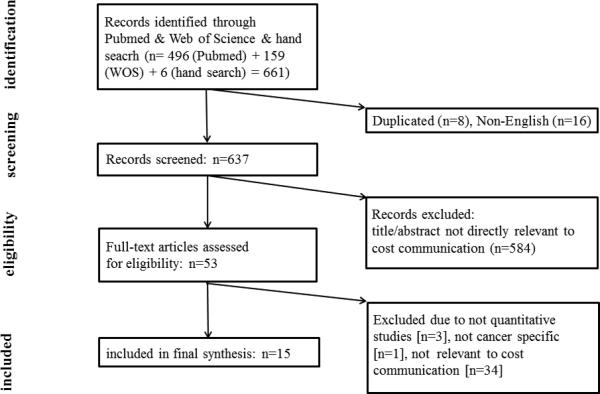

To better understand the role of “cost communication” in cancer care, we conducted a literature search in May 2016. Our inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed English-language full-text articles with information regarding patients’ and/or healthcare providers’ communication about cost of cancer care. We focused on articles published after the ASCO Cost of Care Taskforce released its Guidance Statement in August 2009. An initial search strategy with (cost communication) AND (cancer) as search terms yielded 6 articles published since August 2009, a strikingly small number considering people's interest level and the importance of this topic. We thus developed a more aggressive search strategy to maximize the number of articles identified by utilizing two on-line databases: PubMed and Web of Science (WoS).

Our search strategy started with a PubMed search. We applied search filters with the following search terms: (cancer) AND ((discuss*[title]) OR (experience*[title]) OR (attitude*[title]) OR (communicat*[title])) AND ((“costs and cost analysis”[MeSH] OR costs[Title/Abstract] OR cost effective*[Title/Abstract]) OR (cost*[Title/Abstract] OR “costs and cost analysis”[MeSH:noexp] OR cost benefit analys*[Title/Abstract] OR cost-benefit analysis[MeSH] OR health care costs[MeSH:noexp])). Based on the assumption that the ASCO Cost of Care Taskforce Guidance Statement would ignite the cancer community's interests in cost communication, we then searched the WoS for articles that cited the Taskforce's Guidance Statement.5 After removing duplicates and non-English articles, potentially relevant studies were selected independently by the authors of this article after reviewing the titles and abstracts. Articles to be included in this paper were determined via full-text reviews; disagreement was resolved through discussions.

We summarized articles included in our review under three themes: (A) studies that explored patients’ attitudes toward cost communication, (B) studies of physicians’ acceptance of cost communication, and (C) studies that reported outcomes (e.g., medication adherence, patient satisfaction) associated with cost communication. We synthesized information retrieved from studies under each theme in three summary tables with the following common elements: (a) authors, year of publication, and country; (b) population and characteristics; (c) site; (d) sample size; (e) percentage of study participants who expressed a desire to discuss costs; (f) percentage of study participants who actually discussed costs; and (g) comments that highlight other key components of each study. For elements (e) and (f), the two primary outcomes of interests in our review, we included the exact question that was asked in the Supplemental Material. We reported the weighted means (weighted by the study sample size), medians, and ranges in our synthesis of the literature. For the summary table for studies under theme (C) we replaced element (e) above with a column that described outcomes associated with cost communication. These elements were adopted, with modifications, from a previous study that surveyed breast cancer patients to understand their attitudes toward addressing costs.10

RESULTS

We depicted our literature search process in a flowchart suggested by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).11 Our initial search of PubMed and WoS identified 661 articles. After removing duplicated or non-English studies and reviewing the title and abstract to remove irrelevant studies from the remaining papers, 53 were left for full-text reviews. Further exclusion of articles that did not meet our inclusion criteria after the full-text reviews resulted in a total of 15 papers to be reviewed herein. These papers covered 12 distinct studies as research teams sometimes published multiple papers from one study.

Of the 15 papers, two were developed from the same survey of medical oncologists in the US and Canada,9, 12 two from a survey of a convenient sample of 300 cancer patients,13, 14 and another two from retrospective analysis of transcribed dialogue collected from over 1,500 outpatient encounters.15, 16 Some studies covered more than one theme (Supplemental Table 1). For example, the study by Kelly et al. touched on both patients’ and physicians’ attitudes toward cost communication and the associated outcomes.17

Patient Attitude

Twelve papers from 10 distinct studies investigated patient attitude regarding cost communication10, 13-23 (Table 1, Supplemental Table 2). Nearly all studies took place in the US, except for an Australian study.22 Seven collected information from questionnaires, two from semi-structured interviews,19, 21 and another from content analysis of transcribed dialogue from audio-recorded clinical encounters.15, 16 The median sample size was 133, ranging from 22 (a qualitative analysis)21 to 677 (encounters in breast cancer clinics).15, 16 Over half of these studies recruited participants from cancer patients currently or previously treated in academic cancer centers or their affiliated oncology clinics.10, 13, 14, 17-20 Three studies focused on breast cancer10, 15, 16, 22, one on prostate cancer19, and others did not focus exclusively on a specific cancer. Most studies were not restricted to a particular cancer stage, except for one that focused on metastatic cancers.17

Table 1.

Summary of Articles that Examined Patients’ Attitudes toward Cost Communications

| Author (year), Country | Population and Characteristics | Site | Sample Size | Willingness to Discuss Costs, % | Costs Discussed, % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kelly et al (2015)17, USA | - previously treated metastatic breast, lung, or colorectal cancer pts - 51.1% annual household income > $60,000 - 100% insured |

single institution | 96 | Over 80% - quite or extremely important to know what they would be paying |

28% - inferred from 72% reporting never had cost discussions |

- patients recruited through participating physicians - show cost per cycle using web-based eviti Advisor - data collected using questionnaire |

| Bestvina et al (2014),13 USA Zafar et al (2015),14 USA |

- adults receiving anticancer therapy - 80% income > $60,000 - 100% insured, 56% private |

1 academic cancer center+3 affiliated rural oncology clinics | 300 | 52% had some desire to discuss OOP cost 51% wanted physicians to consider costs when making treatment decisions |

19% discussed treatment-related OOP cost | - convenience sample from participating sites - focused on OOP costs - data collected via interviews, baseline and 3-month follow-up - 16% high/overwhelming financial distress, measured using IFDFW scale - 76% thought physicians did not know patients’ OOP costs |

| Irwin et al (2014),10 USA | - breast cancer pts within 5 yrs of initial diagnosis - 59% annual income ≥ $50,000 - 98% insured |

single institution, academic medical center | 134 | 94% felt physicians should talk to pts about costs of care 62% felt physicians should wait for pts to initiate discussion |

14% discussed costs | - self-administered, anonymous paper survey - 28% stage IV, 46% on cancer treatment at the time of survey - 44% at least moderate level of financial distress, measured using IFDFW scale - 32% financial hardship due to cancer care costs - 85% medical decisions not affected by costs outside OOP - more interested in OOP costs, less in societal costs |

| Kaser et al (2010),22 Australia | - breast cancer pts - 77% insured |

a national organization | 47 | 96% wished to be informed about high-cost drugs, regardless of affordability | 28% discussed high cost drugs with oncologists | - email recruit from BCNA - focused on high cost drugs - telephone interview - of those who discussed, none declined treatment due to financial concerns - 89% comfortable to discuss finances w/ physicians |

| Hunter et al# (2016),16 USA Hunter et al# (2016),15 USA |

- breast cancer pts - 100% insured |

nationwide community-based practices | 677 breast oncology encounters |

Not asked | 22% visits contained cost conversations; of those 38% discussed cost-saving strategies 16% OOP cost 22% cost/coverage* 24% COI+ |

- retrospective, mixed-method analysis of transcribed dialogue from 1755 outpatient visits, sampled from a database of audio-recorded clinical encounters - not limited to cancer, also included pts with depression (n=422), and RA (n=656) - majority of cost conversations were initiated by physicians - second paper focused on different definitions of “costs” to quantify the incidence of cost conversation |

| Meisenberg et al (2015),23 USA | - pts receiving RT or IV chemotherapy - 61% household income ≥ $50,000 - 98% insured - 73% had cancer diagnosed in previous yr |

single institution, outpatient cancer center | 132 | 20% - should receive cost information from oncologists | 26.9% - inferred from 73.1% who rarely talked to oncologists about costs | - convenience sample survey - 47% high financial distress, measured by Pearson Financial Wellness Scale - 6.1% reduce medication adherence due to cost of care - few wanted personal finance (11%) or societal costs (10%) to affect deciding treatment option - 28% wanted the lower-cost regimen even if equally effective |

| Bullock at al (2012),18 USA | - pts with solid tumor malignancies - 61% annual income ≥ $50,000 - 97% insured |

single institution, outpatient oncology unit at an academic center | 256 171 w/medical record review |

59% wanted to discuss OOP costs w/physicians 76% comfortable discussing costs w/physicians |

Not asked | - convenience sample, self-administered questionnaire - 30% preferred discussing costs w/ someone other than their physicians - 25% difficult paying cancer care, 14% financial hardship - when making treatment decision, 57% did not consider OOP costs, 42% did not wish their physicians to |

| Henrikson et al (2014),21 USA | - cancer pts receiving chemo at oncology clinics - 77% household income > $50,000 - 100% insured |

a nonprofit integrated healthcare system | 22 | Not asked | 23% discussed with physicians 36% discussed with other health professionals |

- pts identified via administrative data - semi-structured telephone interview - no pts reported provider-initiated cost discussions - 54.5% financial concerns related to treatment - 60% physicians were the preferred starting point for cost discussions, 9% physicians should not be cost-concerned |

| Zafar et al (2013),20 USA | - pts with solid tumors receiving chemo or hormonal therapy - 22% annual household income ≥ $40,000 - 100% insured |

academic medical center + a national copayment assistance foundation | 254 | Not asked | 58% discussed with physicians | - baseline survey plus 4 monthly cost diaries - 63% completed at least one cost diary, among those 55% were underinsured@ - 75% applied drug copayment assistance, >25% of them did not discuss costs w/ physicians - 42% significant or catastrophic subjective financial burden - primary aim was to understand the impact of copayment assistance among insured cancer pts |

| Jung et al (2012),19 USA | - pts with localized prostate cancer, treated with surgery or RT in previous 6-18 months - 54% annual income ≥ $60,000 - 100% insured |

single institution, academic medical center | 41 | 61% would like doctor to discuss OOP costs when making treatment recommendation | Not asked | - primary goal: understand pts’ perceptions of treatment-related OOP costs and their effects - recruited from urology and radiation oncology clinics - semi-structured interview + questionnaire - 73% not burdened by OOP costs, 83% treatment choice not affected by OOP costs - when making medical decision: 32% physicians should consider pts’ OOP costs, 37% should consider country's healthcare costs |

only numbers related to breast cancer was subtracted

cost/coverage: included discussion of patients’ OOP costs or insurance coverage

COI: cost-of-illness, discussion of financial costs or insurance coverage related to health or healthcare

underinsurance was defined as insured patients whose spent 10% or more of their annual household income on healthcare; BCNA: Breast Cancer Network Australia; chemo: chemotherapy; IFDFW: InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being; IV: intravenous; OOP: out-of-pocket ; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; RT: radiation; pts: patients.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants in these studies reflected more affluent study cohorts. Of the eight studies that reported patients’ income level, seven had more than half of the study participants reporting income level above $50,000, which was close to the 2014 median household income of $53,657 reported by US Census Bureau.24 Only one study had the majority (78%) of patients with an annual household income less than $40,000; however, this was driven by the study's focus on insured cancer patients who requested copayment assistance.20 Interestingly, the lowest rate of insured individual (77%) was found in the Australian study22; all US studies reported high rates of insurance (≥98%). Six studies (seven papers) asked cancer patients about financial distress10, 13, 14, 18, 20, 21, 23 and the reported percentages ranged from 16%13, 14 to 47%.23

Seven studies (eight papers) ascertained patients’ attitudes toward cost communication.10, 13, 14, 17-19, 22, 23 The mean (weighted) and median of the proportion of patients who were surveyed or interviewed and expressed a positive attitude toward cost discussions was 60% and 61%, respectively, and the range was 20%23 to 96%22. Of those, six reported that more than half of study participants were in favor of cost communication. Eight studies (ten papers) inquired whether cancer patients actually had discussed costs with their physicians.10, 13-17, 20-23 The mean (weighted) and median of the proportion of patients who had such conversations was 27% and 25%, respectively, and the range was 14%10 to 58%.20 All but one study reported less than one-third of their study participants had discussed costs with their physicians. The high percentage reported in Zafar et al. (2013)20 likely reflected the study's focus on insured cancer patients who sought copayment assistance.

Physician Acceptance

Five studies (seven papers) reported physician acceptance regarding cost communication9, 12, 15-17, 21, 25 (Table 2, Supplemental Table 3). Three studies (four papers) also explored patient attitude and that information was included in the section above. All studies included oncologists in the US, and one surveyed both US and Canadian oncologists.12 Two studies collected information from self-administered questionnaires9, 12, 25, another two from interviews,17, 21 and one from transcribed dialogue of audio-recorded clinical encounters.15, 16 Two studies recruited study participants by contacting members of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO)9, 12, 25 and one included only oncologists in an academic setting.17 While all studies included oncologists, one focused exclusively on medical oncology,9, 12 and another also added a physician assistant to the interview pool.21 The sample size varied from 11 in a more qualitative study21 to 925 in a large scale survey.9, 12

Table 2.

Summary of Articles that Reported Physicians' Attitude toward Cost Communications

| Author (year), Country | Population and Characteristics | Site | Sample Size | Willingness to Discuss Costs, % | Costs Discussed, % | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berry et al (2010),12 USA and Canada Neumann et al (2010),9 USA |

- medical oncologists - mean years of practice: 23.8 [USA], 23.2 [Canada] |

National organizations, ASCO in USA and various medical societies in Canada | 941 787 [US] 154 [Canada] |

Not asked | 43% [USA] 48% [Canada] always or frequently discuss costs of new cancer treatments |

- Mail survey for US oncologists, mail or web-based survey for Canadian oncologists - 84% US, 80% Canada: OOP costs affects treatment recommendation - 67% US, 52% Canada: pts should have access to effective cancer drugs regardless of costs - Neumann et al reported the US portion of this study |

| Henrikson et al (2014),21 USA | - physicians and physician assistants at oncology clinics - 15.5 mean yrs in practice |

a nonprofit integrated healthcare system | 11 | Not asked | 5%- 66% frequency of cost discussions | - semi-structured telephone interview - source of cost data: colleagues most common, >25% from pts - >90% cost information should be readily available |

| Kelly et al (2015),17 USA | - university faculty (oncologists) specialized in treating breast, lung, or colorectal cancer | single institution | 18 | 28% felt comfortable | 6% frequently, 17% sometimes, 55% a little, 22% never | - participating providers helped identify eligible patients to assess ratings of cost communications - provided a standard script - showed cost per cycle via web-based eviti Advisor - data collected via interviews |

| Hunter et al# (2016),16 USA Hunter et al# (2016),15 USA |

- oncologists - 89% male, 63% in practice > 10 years |

nationwide community - based practices | 56 oncologist | Not asked | 22% visits contained cost conversations 16% OOP cost 22% cost/coverage+ 24% COI* |

- retrospective, mixed-method analysis of transcribed dialogue from 1755 outpatient visits, sampled from a database of audio-recorded clinical encounters - not limited to cancer, also included 36 psychiatrics and 26 rheumatologists - majority of cost conversations were initiated by physicians - second paper focused on different definitions of “costs” to quantify the incidence of cost conversation |

| Altomere et al (2016),25 USA | - ASCO members - 35% medical oncologist, 35% radiation oncologist, 31% surgeon - 45% academic, 55% community/private practice - 77% male; 76% white |

a random sample of ASCO physician members | 333 | 75% physicians' responsibility to discuss OOP costs in treatment decision 53% physicians' responsibility to discuss societal costs |

60% addressed costs frequently or always in clinic 6% never discussed |

- self-administered anonymous electronic survey - 94% always or mostly offered all treatment options regardless of costs - 79% felt patients should choose cheaper option if treatments are equally effective - 36% felt explaining costs to patients was not physicians' responsibility - major barriers: don't know enough about costs of care, lack resources |

only numbers related to breast cancer was subtracted

cost/coverage: included discussion of patients' OOP costs or insurance coverage

COI: cost-of-illness, discussion of financial costs or insurance coverage related to health or healthcare; ASCO: American Society of Clinical Oncology; OOP: out-of-pocket

Two studies inquired about physician comfort level toward cost communication; one reported that 28% felt comfortable with it17 and another found that 75% of physicians consider it their responsibility to discuss out-of-pocket costs with their patients when making treatment decisions.25 No weighted mean was reported due to the vast difference in sample size between these two studies (18 vs. 333). Three studies asked physicians whether cost communication was frequent in their practice, and the proportion reporting that they always or frequently discussed costs with their patients ranged from 6%17 to 60%,25 with a weighted mean of 47%. The study that analyzed dialogue at encounter level reported that 22% of the visits contained cost conversations.15, 16 Another small sample (n=11) study asked physicians the frequency of cost communication, and the reported percentage varied widely, between 5% to 66%.21

Two studies investigated the relationship between costs and treatment recommendation.9, 12, 25 In one study, 94% of physicians said that physicians should offer all treatment options regardless of costs.25 In another study, 52% (Canadian oncologists) to 67% (US oncologists) felt that patients should have access to effective cancer drugs regardless of costs.12 These two studies also revealed that physicians were cost conscious. Berry et al. (2010) reported 84% of oncologists in the US and 80% in Canada felt out-of-pocket costs affected their treatment recommendation,12 whereas 79% of physicians in Altomere et al (2016) agreed that the cheaper option should be chosen when two treatments were equally effective.25

Outcomes

Three papers (two studies) explored the association between patient-physician cost communication and three aspects of cancer care: patient satisfaction,17 medication non-adherence,13 and out-of-pocket costs14 (Table 3). Both were US studies, with study participants recruited primarily from academic cancer centers and/or the affiliated oncology clinic. Participants in both studies were insured cancer patients and more than 50% of them had a household income above $60,000.

Table 3.

Summary of Articles that Examined Outcomes Associated with Cost Communication

| Author (year), Country | Population and Characteristics | Site | Sample Size | Costs Discussed, % | Outcome | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kelly et al (2015),17 USA | - Previously treated metastatic breast, lung, or colorectal cancer patients - 51.1% annual household income > $60,000 - 100% insured |

single institute | 96 | 28% | Satisfaction: 81.2% had no negative feelings or conflicts when discussing costs with providers | - patients recruited through participating physicians - patient satisfaction measured using Satisfaction with Decision Scale - data collected using questionnaire |

| Bestvina et al (2014),13 USA Zafar et al (2015),14 USA |

- adults receiving anticancer therapy - 80% income > $60,000 - 100% insured, 56% private |

1 academic cancer center+3 affiliated rural oncology clinics | 300 | 19% |

Non-adherence: higher odds of non-adherence with cost discussion [OR=2.58, 95% CI, 1.14 to 5.85] OOP costs: 57% lower costs due to cost discussions |

- convenience sample from participating sites - focused on OOP costs - 27% nonadherence, self-reported - data collected via in person interviews at baseline and 3-month in person or phone follow-up |

NOTE: OOP: out-of-pocket; OR: odds ratio; CI: confidence interval

Kelly et al. asked oncologists in an academic setting to discuss financial difficulties with their patients at the end of their clinical encounters.17 Cost information was provided using eviti ADVISOR, a web-based oncology decision support platform. Assessment of patient satisfaction ratings regarding cost communication showed 80% of patients had no negative feelings about hearing cost information, suggesting that the majority of patients considered cost communication satisfactory. Bestvina et al. analyzed the association between cost discussions and medication non-adherence and reported cost discussions to be associated with higher odds of medication non-adherence [(odds ratio 2.58; 95% confidence interval, 1.14 to 5.85)].13 Using data from the same survey, Zafar et al. showed that among the 19% of patients who discussed costs with their physicians, 57% reported lower out-of-pocket costs as a result of that discussion.14

DISCUSSION

This article provides a comprehensive literature review on three topics of patient-physician cost communication in the context of cancer care: patient attitude, physician acceptance, and outcomes associated with such communication. We identified 15 articles that covered at least one of these topics. Collectively, our review suggested that although cost communication was desired by more than half of patients in most of the study cohorts, less than one-third of patients had actually discussed costs with their physicians. The combined literature also indicated that despite 75% of physicians considered it their responsibility to discuss out-of-pocket cost with patients, less than 30% felt comfortable with such communication. When asked whether cost communication actually took place, the percentages reported by physicians varied widely across studies, from less than 10% to over 60%. Furthermore, cost communication was found to be associated with improved patient satisfaction, lower out-of-pocket expenses, and a higher likelihood of medication non-adherence; the exact reason(s) and possible causal pathway influencing the latter observation remain enigmatic.

Patient-physician cost communication can potentially improve cost transparency from the patients’ perspective. A critical element to achieve this is to have accurate cost information, including insurance coverage policies. Specifically, while patients and their families look to their physicians to help them better understand the cost implication of their treatment choices, physicians who are willing to undertake this challenging task need to have accessible and comprehensible cost information to facilitate the discussion. One study documented that although over 50% of patients expressed some desire to discuss out-of-pocket costs, 76% of them felt that their physicians had no such knowledge.13, 14 Indeed, two studies reported that physicians lacked knowledge of or accessibility to cost information, which were major barriers to cost communication.21, 25 Several web-based sources have been developed to provide estimates of cancer care costs. For example, eviti ADVISOR was used in Kelly et al. to assist oncologists in discussing costs,17 and DrugAbacus offers an interactive tool online to allow consumers to compare prices of cancer drugs. It should be noted that neither source builds in the capability to customize their cost calculations by insurance benefit design. As such, cost information obtained from these sources does not directly inform patients of their out-of-pocket expenses and may be of limited use in improving cost transparency through patient-physician cost communication.

The wide range (20% to 96%) of the proportion of patients expressing a positive attitude toward patient-physician cost communication may reflect the difference across studies in the specific question that was asked. In our review, questions related to the topic of “patient attitude” can be broadly categorized into two types: those that asked whether patients “want to” or “would like to” discuss cost with their doctors13, 14, 18, 19 vs. those that asked whether patients “should be” or “wished to be” informed.10, 17, 22, 23 Studies asking the former type of questions reported percentages in the 50-60% range, whereas those with the latter type tended to report high percentages, except for the 20% reported in one study that asked whether patients should receive cost information from their oncologists.23 This observation suggests that to some extent the reported percentages were influenced by the framing of the questions. The literature also provided some clue as to why some patients did not want to discuss costs with their physicians. Zafar et al. found that 34% of patients did not discuss costs with their doctors because they wanted to receive “the best possible care regardless of costs,”14 implying a concern on the patients side that patient-physician cost communication might jeopardize their chance of receiving “the best” treatment. A potential solution is to offer patients the option to discuss costs with other personnel such as social workers or navigators in the clinic as Bullock et al. have found that 30% of patients preferred discussing costs with someone other than their physicians.18

Affirming patient-physician cost communication as a critical component of quality cancer care was forward-thinking at the time the ASCO Cost of Cancer Care Task Force released their guidance statement. Interestingly, this assertion went largely uncontested over the years. It had been assumed that upfront cost discussions would help patients evaluate the financial implications of their treatment choices to make an informed decision. The limited evidence from the literature suggested that cost communication was associated with better care quality if quantified as patient satisfaction17 and lower out-of-pocket costs.14 However, no studies had employed more rigorous study design (e.g., randomized trials or pre-post interventions) to critically evaluate whether patient-physician cost communication would indeed lead to better quality of care or whether the same effect could be achieved by communication between patients and other non-physician personnel. Also lacking in the literature was a roadmap to assist financially distressed patients had such need been detected in the cost communication.

Many believe that patient-physician cost communication could ultimately reduce healthcare cost through minimizing the use of lower value therapies.26-28 However, several studies indicated cancer patients, especially those undergoing active treatment, tended not to be cost-sensitive.18, 19, 23 In Meisengberg et al. only 28% of patients were willing to select the lower cost option when presented with two hypothetical treatments that had equal effectiveness but differed in costs.23 Moreover, Irwin et al. found that when both out-of-pocket and overall costs to the healthcare system were queried, patients were less sensitive to the societal costs.10 Our review also suggested that while oncologists recognized out-of-pocket costs could affect treatment decisions, many believed that patients should have access to effective treatments regardless of costs. These observations cast doubts on whether patient-physician cost communication can be an effective avenue to reduce overall healthcare costs.

Two study limitations warrant discussion. First, our inclusion of studies published after August 2009 was based on the assumption that the release of ASCO's Cost of Cancer Care Guidance Statement would inspire more research on the topic of patient-physician cost communication in oncology. This inclusion criterion should not cause a large amount of information loss as a review article published in 2010 concluded that this topic was “largely understudied.”28 Second, although the vast majority of studies in our review were conducted in the US, the extent to which findings summarized here represent the view of American cancer patients should be explored in future research as information available in the literature was mostly collected from cancer patients with selected characteristics, such as patients who were recruited from academic medical centers, carried health insurance, and had an income higher than the median household income in the US. The larger representation of more affluent patients in these studies would likely be associated with stronger desire to communicate with their physicians on any aspect of their care, including costs. It is therefore reasonable to expect that the conclusions from our review may not be generalizable to less affluent subgroups of patients.

Cost communication has grown increasingly important as patients and physicians are under immense pressure to sustain the affordability of cancer care today. The literature indicated that while patients and physicians did not object to cost communication, such communication did not occur frequently. To facilitate effective cost communication, efforts must be made to generate and disseminate accurate, accessible, and transparent cost information. Future research should also employ rigorous study designs to explore the effect of cost communication on various dimensions of cancer care quality.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) chart that depicts the literature search process. Search was conducted in two databases: PubMed and Web of Science.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Shih, R01 HS020263), National Cancer Institute (Shih, R01 CA207216), and China Medical University Hospital (Chien, DMR-105-151). The authors thank Gary Deyter for his editorial assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hillner BE, Smith TJ. Do the large benefits justify the large costs of adjuvant breast cancer trastuzumab? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:611–613. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.3542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schrag D. The price tag on progress--chemotherapy for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:317–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scalo JF, Rascati KL. Trends and issues in oncology costs. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14:35–44. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.864561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shih YC, Ganz PA, Aberle D, et al. Delivering high-quality and affordable care throughout the cancer care continuum. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4151–4157. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.0651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: the cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3868–3874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.IOM. Delivering high-quality cancer care: Charting a new course for a system in crisis. Institute of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alexander GC, Casalino LP, Meltzer DO. Patient-physician communication about out-of-pocket costs. JAMA. 2003;290:953–958. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schrag D, Hanger M. Medical oncologists' views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: a pilot survey. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:233–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann PJ, Palmer JA, Nadler E, Fang C, Ubel P. Cancer therapy costs influence treatment: a national survey of oncologists. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:196–202. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Irwin B, Kimmick G, Altomare I, et al. Patient experience and attitudes toward addressing the cost of breast cancer care. Oncologist. 2014;19:1135–1140. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:264–269, W264. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berry SR, Bell CM, Ubel PA, et al. Continental Divide? The attitudes of US and Canadian oncologists on the costs, cost-effectiveness, and health policies associated with new cancer drugs. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4149–4153. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bestvina CM, Zullig LL, Rushing C, et al. Patient-oncologist cost communication, financial distress, and medication adherence. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:162–167. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zafar SY, Chino F, Ubel PA, et al. The utility of cost discussions between patients with cancer and oncologists. Am J Manag Care. 2015;21:607–615. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunter WG, Hesson A, Davis JK, et al. Patient-physician discussions about costs: definitions and impact on cost conversation incidence estimates. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:108. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1353-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hunter WG, Zhang CZ, Hesson A, et al. What Strategies Do Physicians and Patients Discuss to Reduce Out-of-Pocket Costs? Analysis of Cost-Saving Strategies in 1755 Outpatient Clinic Visits. Med Decis Making. 2016 doi: 10.1177/0272989X15626384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly RJ, Forde PM, Elnahal SM, Forastiere AA, Rosner GL, Smith TJ. Patients and Physicians Can Discuss Costs of Cancer Treatment in the Clinic. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:308–312. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.003780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bullock AJ, Hofstatter EW, Yushak ML, Buss MK. Understanding patients' attitudes toward communication about the cost of cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e50–58. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung OS, Guzzo T, Lee D, et al. Out-of-pocket expenses and treatment choice for men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2012;80:1252–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient's experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henrikson NB, Tuzzio L, Loggers ET, Miyoshi J, Buist DS. Patient and oncologist discussions about cancer care costs. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:961–967. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2050-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaser E, Shaw J, Marven M, Swinburne L, Boyle F. Communication about high-cost drugs in oncology--the patient view. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1910–1914. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meisenberg BR, Varner A, Ellis E, et al. Patient Attitudes Regarding the Cost of Illness in Cancer Care. Oncologist. 2015;20:1199–1204. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeNavas-Walt C,DPB. Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014. U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports; Washington, DC: 2015. pp. P60–252. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Altomare I, Irwin B, Zafar SY, et al. Physician Experience and Attitudes Toward Addressing the Cost of Cancer Care. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:e281–288, 247-288. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.007401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schickedanz A. Of value: A discussion of cost, communication, and evidence to improve cancer care. Oncologist. 2010;15(Suppl 1):73–79. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2010-S1-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peppercorn J. The financial burden of cancer care: do patients in the US know what to expect? Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14:835–842. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.963558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hofstatter EW. Understanding patient perspectives on communication about the cost of cancer care: a review of the literature. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:188–192. doi: 10.1200/JOP.777002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.