Abstract

Faecal samples of cattle and buffaloes of Mumbai region collected between November 2012 to June 2013 were analysed by conventional and molecular tools to note the prevalence of cryptosporidiosis and species involved in the infection. Conventional analysis viz., direct faecal smear examination, faecal smear examination after normal saline sedimentation, Sheather’s floatation and Sheather’s floatation sedimentation smear methods demonstrated oocysts of Cryptosporidium in 141 (36.06 %) of 391 samples with higher occurrence in buffaloes (36.99 %) than cattle (34.48 %). Diarrhoeic loose faeces showed higher prevalence (42.07 %) than apparently normal faeces (31.72 %) irrespective of the host species. When data were arranged as per age groups viz., calves of 0–1 month, 1–2 months, 2–3 months and adults, the highest prevalence was noted in the youngest group (47.12 %) declining gradually with the advancing age with lowest (6.25 %) in adults indicating inverse correlation between prevalence rate and age of the host. These differences were statistically significant in case of buffaloes. Cryptosporidium andersoni was tentatively identified by morphometric analysis. By employing molecular tools like nested PCR, PCR–RFLP and sequence analysis of few samples showed good correlation in the identification of species of Cryptosporidium involved in the infection and demonstrated occurrence of C. parvum, C. ryanae and C. bovis. Thus all the four commonly occurring bovine species of Cryptosporidium were encountered in the study area which appears to be a first record reporting the occurrence of Cryptosporidium with species level identification in large ruminants from Western region of India. Additionally, the public health significance of C. parvum was also discussed in light of epidemiological factors pertaining to the region.

Keywords: Cryptosporidium, Cattle, Buffalo, Nested PCR, Mumbai

Introduction

Cryptosporidium is a coccidian parasite occurs in different species of hosts and today the parasite is known to infect more than 150 species of animals belonging to mammalian, avian, reptiles, amphibian and fish (Fayer and Xiao 2008). Worldwide, cattle are commonly infected with 4 Cryptosporidium species viz., C. parvum, C. andersoni, C. ryanae and C. bovis. Further, all these 4 species have also been reported in buffaloes. Bovine cryptosporidiosis is primarily a patent infection in young calves till they attain immunological maturity which is invariably associated with neonatal diarrhoea with higher morbidity than mortality, thus resulting into weight loss and delayed or stunted growth reflecting substantial economic losses. In India, cryptosporidiosis was reported for the first time in faeces of cattle by Nooruddin and Sarma (1987) and in human night soil by Mathan et al. (1985). Apart from causing economic losses to livestock industry, Cryptosporidium. has also gained attention of scientific community as an emerging zoonoses due to its public health significance. Owing to lack of information pertaining to occurrence of the disease in large ruminants of Maharashtra, the present investigation was undertaken to note the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. in cattle and buffalo calves of Mumbai region along with species level identification by employing molecular tools. Hence, the present communication reports the occurrence of four species of Cryptosporidium from Western region of India, which appears to be a first record of its kind from this region.

Materials and methods

Collection of faecal samples and preliminary examination

The faecal samples of 391 animals comprising 125, 218, 20 and 28 cattle calves, buffalo calves, adult cattle and adult buffaloes, respectively were collected between November 2012 to June 2013. The samples were collected per rectally in 50 ml sterile plastic vials and were transferred to laboratory on ice and were stored at 4 °C till use. The samples were processed by 4 different methods viz., direct faecal smear examination (DFSE), faecal smear examination after normal saline sedimentation (NSS), unstained faecal smear examination after Sheather’s floatation (SF) and stained faecal smear after Sheather’s floatation (SFSS) to demonstrate the oocysts of Cryptosporidium spp. The procedures followed in the study were as below.

DFSE

Faecal smears after drying were stained by modified Ziehl Neelsen (mZN) technique (Henricksen and Pohlenz 1981). The smears were fixed with methanol for 5 min and then transiently fixed over the flame. Subsequently, the smears were flooded with carbol fuchsin which was allowed to act for 40 min. The slides washed under running water for 5 min were then decolourised with 10 % H2SO4 for 15–30 s after counter staining these with 5 % malachite green for 5 min. Slides washed under running water for 5 min were dried and examined under high and oil immersion objectives of compound microscope.

Faecal smear examination (FSE) after NSS

Approximately 5 g faecal matter was homogenized in 10 ml normal saline solution. The faecal suspension was sieved through a wire mesh of 400 µ pore size to eliminate coarse particles. The suspension was then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatent was discarded gradually and sediment was used to prepare a faecal smear which was stained with mZN as described earlier.

Unstained faecal smear examination after Sheather’s floatation (SF)

Faecal samples were homogenized in phosphate buffer saline (PBS), sieved through wire mesh (400 µ) and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. After discarding the supernatent the sediment was mixed thoroughly with 10 ml of Sheather’s sugar solution in the centrifuge tubes which were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min (Anderson 1981). The superficial film of suspension was collected gently on a clean glass slide and was examined under high power after putting the coverslip on it.

Stained faecal smear after Sheather’s floatation (SFSS)

The method employed here was same as SF up to centrifugation in Sheather’s sugar solution. Subsequently, 2–3 ml of top layer was aspirated in clean sterilised Pasteur pipette and was diluted 3 times with PBS and centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 5 min. After discarding the supernatent the sediment was used to prepare the faecal smear and on drying it was processed in similar fashion as described in DFSE and were observed under microscope. Oocysts encountered during microscopic examination of the stained smear were measured by using micrometry technique (Rathore and Sengar 2005). In each smear, at least 10 oocysts were measured under high power.

Genomic DNA extraction

Primary purification of the oocysts from faeces was done by modified Sheather’s sucrose floatation technique (Current et al. 1983). For extraction of DNA, oocyst of Cryptosporidium were purified from faecal mass using QIAamp® DNA stool extraction kit according to manufacturer’s protocol with minor modifications.

Nested PCR

A two-step nested PCR protocol was followed to amplify 830 bp fragment of the 18S SSU rRNA gene of Cryptosporidium as described by Paul et al. (2009) by using primary and secondary primers.

Polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR–RFLP)

For genotyping, 9 nested PCR positive products were subjected to PCR–RFLP using the restriction enzymes viz., SspI, VspI and MboII (Fermentas) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Based on the PCR–RFLP banding pattern, Cryptosporidium speciation was performed as per the method described by Feng et al. (2007).

Sequencing of 18s SSU rRNA gene of Cryptosporidium spp.

To confirm the PCR–RFLP results, sequencing of the 9 PCR products was carried out at Xcearis Labs Pvt. Ltd., Ahmadabad (India). Sequences were retrieved from SDSC biology workbench (http://workbench.sdsc.edu). The ABI files were curetted using chromas lite software version 2.01. The curetted sequences were submitted to search their similarity in NCBI database using BLAST tool.

Statistical analysis

The data generated during the study were subjected to Chi square test as per the method described by Snedecor and Cochran (1994).

Results

Prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in large ruminants of Mumbai

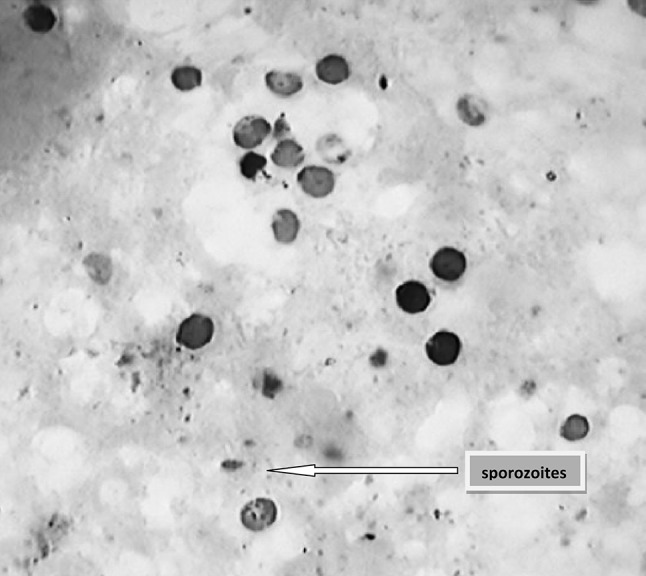

Amongst the 4 methods employed in the present study, SFSS was found to be the most sensitive (82.98 %) while the sensitivity for FSE after NSS, SF and DFSE was 56.74, 33.33 and 24.11 %, respectively (Table 1). For determination of prevalence, the findings of all the 4 techniques were considered in the current study. Amongst 391 tested faecal samples, 141 were found positive with prevalence rate of 36.06 %. The prevalence was non-significantly higher in buffaloes (38.56 %) than cattle (34.48 %). The oocyts encountered in the present study showed great variation in size, shape, intensity and staining reaction. Majority of the stained oocysts were dark pink in colour against green background in smears stained by mZN technique (Fig. 1). The oocyst size of C. andersoni was bigger (5.8–7.2 µ in diameter) than the rest (Upton and Current 1985; Lindsay et al. 2000 and Fayer et al. 2001) and hence C. andersoni could be tentatively identified on the basis of micrometry.

Table 1.

Sensitivity of different conventional methods for diagnosis of cryptosporidiosis in large ruminants

| No. of animals examined | Total +ve | Detection of infection by various methods | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DFSE | SF | FSE after NSS | SFSS | ||

| 391 | 141 | 34 | 47 | 80 | 117 |

| % Sensitivity | 24.11 | 33.33 | 56.74 | 82.98 | |

Fig. 1.

Microscopic image of Cryptosporidium oocysts after mZN staining of faecal smear (×100)

Age-wise, gender-wise and season-wise prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in large ruminants of Mumbai region

Prevalence rate of cryptoporidiosis was found to be higher in <3-month-old calves than adults with significant difference at 5 and 1 % level in cattle and buffaloes, respectively (Table 2). While non-significant difference was in evidence in the occurrence rate of cryptosporidiosis in cattle and buffalo calves. The age-wise prevalence divided in 3 groups viz., 0–1, 1–2 and 2–3-month-old cattle and buffalo calves revealed significant difference (P < 0.01) only in case of buffaloes while in case of cattle it was non-significant, where the highest prevalence was noted in <1-month-old calves. In the present study, out of 48 adult large ruminants, only three (6.2 %) revealed oocysts of Cryptosporidium in the faecal sample. Present study recorded the non-significantly higher prevalence in case of males than females of both the large ruminant species. Season-wise, the prevalence was non-significantly higher in winter (40.5 %) than monsoon (35.63 %) and summer (29.41 %) in both the species of large ruminants.

Table 2.

Age-wise prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in large ruminants

| Category of host | Cattle calves | Buffalo calves | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (months) | No. of animals | No. of +ve cases | % Prevalence | No. of animals | No. of +ve cases | % Prevalence | Total prevalence (%) |

| <3 months | 125 | 48 | 38.40 | 218 | 90 | 41.28 | 40.23 |

| Adult | 20 | 2 | 10 | 28 | 1 | 3.57 | 6.25 |

| Grand total | 145 | 50 | 34.48 | 246 | 91 | 36.99 | 36.06 |

Prevalence of cryptosporidiosis in relation to faecal consistency

The prevalence rate was found non-significantly higher in animals having diarrhoea at the time of collection than those having faeces of normal consistency.

Molecular identification of Cryptosporidium spp.

Nested PCR

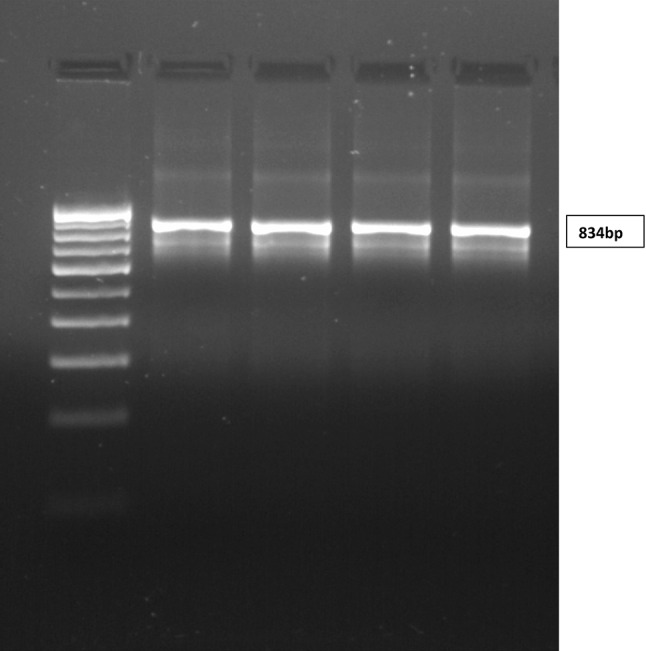

Faecal samples of 6 buffalo and 3 cattle which were positive by conventional techniques were subjected to molecular analysis by nested PCR using 18S rRNA gene specific primers in order to identify the species of Cryptosporidium. Nested PCR of all 9 samples employed in the study exhibited distinct band of ~830 bp on agarose gel confirming the presence of Cryptosporidium spp (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

PCR Products on agarose gel showing 834 bp band

PCR–RFLP

The gel purified Cryptosporidium DNA products were subjected to PCR–RFLP analysis. Thus different restriction enzymes viz., SspI, VspI (Xiao et al. 1999) and MboII (Feng et al. 2007) were employed for digestion of PCR products to obtain various fragments of different sizes (base pairs) electrophoresed on agarose gel. Careful evaluation of RFLP banding pattern on agarose gel depicted in the Table 3 outwardly poses a complex picture. All the 9 cases revealed infection with single species of Cryptosporidium and mixed infection was not recorded in a single case. Out of 3 faecal samples from cattle, 2 revealed C. parvum and remaining one showed C. ryanae infection. Amongst 6 buffalo samples, 3 and 1 revealed positivity for C. ryanae and C. Parvum, respectively, while remaining 2 did not show splitting of fragments.

Table 3.

Results of RFLP–PCR with SspI, VspI and MboII restriction enzymes

| Sr. no. | Results | Restriction enzymes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SspI | VspI | MboII | ||

| 1 | C. parvum | 449, 267, 108 | 628, 115, 104 | 774, 76 |

| 2 | C. ryanae | 432, 267, 103, 33 | 616, 115, 104 | 574, 185, 76 |

| 3 | C. ryanae | 432, 267, 103, 33 | 616, 115, 104 | 574, 185, 76 |

| 4 | C. ryanae | 432, 267, 103, 33 | 616, 115, 104 | 574, 185, 76 |

| 5* | C. parvum | 449, 267, 108 | 628, 115, 104 | 774, 76 |

| 6* | C. parvum | 449, 267, 108 | 628, 115, 104 | 774, 76 |

| 7* | C. ryanae | 432, 267, 103, 33 | 616, 115, 104 | 574, 185, 76 |

Enzyme names are written in bold

* Cattle isolates

Sequencing

The 9 nested PCR amplicons of Cryptosporidium DNA samples were successfully sequenced. The obtained sequence of nested PCR products were analysed by using NCBI BLAST tool and 3 species of Cryptosporidium viz., C. ryane in 4 samples, C. parvum in 3 samples and C. bovis in 2 samples were identified as per Table 4.

Table 4.

Results of sequence analysis of Cryptosporidium spp.

| Sr. no. | Sample no. | Name of the species | Homology (%) | Gene Bank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CRPM1 | C. parvum isolate | 99 | KC569976.1 |

| C. parvum gene | 99 | AB513881.1 | ||

| 2 | CRPM2 | C. bovis isolate | 99 | HQ179573.1 |

| C. bovis gene | 99 | AB746197.1 | ||

| 3 | CRPM3 | C. ryanae gene | 99 | AB746196.1 |

| 4 | CRPM4 | C. ryanae isolate | 99 | JN400880.1 |

| C. ryanae gene | 99 | AB746196.1 | ||

| 5 | CRPM5 | C. ryanae isolate | 100 | JX559847.1 |

| C. ryanae gene | 100 | AB712387.1 | ||

| 6* | CRPM6 | C. parvum isolate | 99 | JX298603.1 |

| C. parvum frm IRAN | 99 | HQ651731.1 | ||

| 7* | CRPM7 | C. parvum strain | 83 | KC662502.1 |

| C. parvum gene | 83 | AB746195.1 | ||

| 8* | CRPM8 | C. ryanae isolate | 99 | JX237831.1 |

| C. ryanae gene | 88 | AB712388.1 | ||

| 9 | CRPM9 | C. bovis isolate | 99 | JX416364.1 |

| C. bovis gene | 98 | AB441689.1 |

* Cattle isolates

Discussion

The present study clearly demonstrated that no single conventional method is adequate to detect cent per cent cases of cryptosporidiosis. Even higher sensitivity (82.98 %) of SFSS indirectly reflects that 17.02 % (24) cases were missed out by this method. These 24 samples which were negative by SFSS evinced positivity with one or more of the remaining three methods. Since cryptosporidiosis in bovines is usually subclinical or chronic self-limiting infection particularly in young calves and immunocompetent individuals, the combined sensitivity of SFSS and NSS appears to be satisfactory.

The prevalence of cryptosporidiosis was found to be marginally higher in buffaloes than cattle. In both the species of large ruminants, the prevalence was distinctly higher in calves below 3 months of age than adults. Further, split of age-wise data into three subgroups viz., 0–1, 1–2 and 2–3 month-old-calves, revealed highest prevalence in calves below 1 month of age. In general, it was evident that, the age-wise prevalence differed significantly in different age groups. Age predisposition of bovine cryptosporidiosis with higher rate in young calves has now been a well-established fact. Further, the present survey also demonstrated that the infection was common in calves below 3 months of age in Mumbai region and hence special efforts need to be taken to detect, treat and control these infections to curb the economic losses.

The PCR–RFLP analysis of the few representative samples showed presence of C. ryanae and C. Parvum. The comparison also revealed that, RFLP with VspI and MboII is adequate to differentiate bovine species of Cryptosporidium and SspI does not add to the diagnostic value. Venu et al. (2012) also categorically concluded that RFLP analysis of nested PCR product of 18 S rRNA gene could differentiate two of the commonly occurring Cryptosporidium spp. viz., C. ryanae and C. bovis based on MboII restriction enzyme. Thus RFLP analysis with VspI and MboII can be used for species level identification in large scale epidemiological surveys. The comparison of PCR–RFLP and sequence analysis results showed good correlation although sequence analysis also showed homology with C. bovis which was not detected by RFLP analysis.

Since this is the first study on cryptosporidiosis in large ruminants of Mumbai and Maharashtra, the main objective of the study was to identify the species of Cryptosporidium prevailing in the region. Thus molecular studies including RFLP and sequence analysis clearly indicate presence of three species viz., C. ryanae, C. parvum and C. bovis in large ruminants of Mumbai region. These findings are in general agreement with the observations of Paul et al. (2008), Venu et al. (2012) and Khan et al. (2010) from different regions of India, South Indian states and West Bengal region, respectively. Although C. andersoni was not detected during molecular analysis due to limited number of samples, it was tentatively detected in 9 faecal samples by micrometric evaluation of the oocysts.

By combining the findings of conventional and molecular tools, it can be concluded that, all four common species of Cryptosporidium viz., C. parvum, C. bovis, C. ryanae and C. andersoni are prevalent in Mumbai which appears to be a first report of occurrence of these species from this region. Occurrence of C. parvum, a well known zoonotic opportunistic protozoa in calves predominantly reared in unhygienic conditions in Mumbai region was considered as a serious public health hazard to associated human population in general and immunocompromised individuals in particular.

References

- Anderson BC. Patterns of shedding of cryptosporidial oocysts in Idaho calves. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1981;178:982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Current WL, Reese NC, Ernst JV, Bailey WS, Heyman MB, Weinstein WM. Human cryptosporidiosis in immunocompetent and immunodeficient persons. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:1252–1258. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198305263082102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R, Xiao L. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. 2. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2008. p. 560. [Google Scholar]

- Fayer R, Trout JM, Xiao L, Morgan UM, Lal AA, Dubey JP. Cryptosporidium canis n. spp. from domestic dogs. J Parasitol. 2001;87:1415–1422. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[1415:CCNSFD]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Ortega Y, He G, Das P, Xu M, Zhang X, Fayer R, Gatei W, Cama V, Xiao L. Wide geographic distribution of Cryptosporidium parvum and deer like genotype in bovines. Vet Parasitol. 2007;144:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henricksen SA, Pohlenz JFL. Staining of cryptosporidia by a modified Ziehl–Neelsen technique. Acta Vet Scand. 1981;22:594. doi: 10.1186/BF03548684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SM, Debnath C, Pramanik AK, Xiao L, Nozaki T, Ganguly S. Molecular characterization and assessment of zoonotic transmission of Cryptosporidium from dairy cattle in West Bengal. J Vet Parasitol. 2010;171:41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay DS, Upton SJ, Owens DS, Morgan UM, Mead JR, Blagburn BI. Cryptosporidium andersoni n. spp. (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporiidiae) from cattle, Bostaurus. J Euk Microbiol. 2000;47:91–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2000.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathan MM, Venkatesan S, George R, Mathew M, Mathan VI. Cryptosporidium and diarrhoea in southern Indian children. Lancet. 1985;2:1172–1175. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(85)92691-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nooruddin M, Sarma DK. Role of Cryptosporidium in calf diarrhoea. Livestock Advisor. 1987;12:49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Chandra D, Ray DD, Tewari AK, Rao JR, Banerjee PS, Baidya S, Raina OK. Prevalence and molecular characterization of bovine Cryptosporidium isolates in India. Vet Parasitol. 2008;153:143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul S, Chandra D, Tewari AK, Banerjee PS, Ray DD, Raina OK, Rao JR. Prevalence of Cryptosporidium andersoni: a molecular epidemiological survey among cattle in India. Vet Parasitol. 2009;161:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathore VS, Sengar YS. Diagnostic parasitology. 1. Jaipur: Pointer Publishers; 2005. pp. 113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. 8. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Upton SJ, Current WL. The species of Cryptosporidium (Apicomplexa: Cryptosporidiidae) infecting mammals. J Parasitol. 1985;71:625–629. doi: 10.2307/3281435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venu R, Latha BR, Basith SA, Raj GD, Sreekumar C, Raman M. Molecular prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp. in dairy calves in Southern states of India. Vet Parasitol. 2012;188:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Escalante L, Yang C, Sulaiman I, Escalante AA, Monsali RJ, Fayer R, Lal AA. Phylogenetic analysis of Cryptosporidium parasites based on the SSU rRNA gene locus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1578–1583. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1578-1583.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]